Abstract

A mechanism for the oxygenation of Cu(I) complexes with α-ketocarboxylate ligands is elaborated that is based on a combination of density functional theory and multireference second-order perturbation theory (CASSCF/CASPT2) calculations. The reaction proceeds in a manner largely analogous to those of similar Fe(II) α-ketocarboxylate systems, i.e. by initial attack of a coordinated oxygen molecule on a ketocarboxylate ligand with concomitant decarboxylation. Subsequently, two reactive intermediates may be generated, a Cu-peracid structure and a [CuO]+ species, both of which are capable of oxidizing a phenyl ring that is a component of the supporting ligand. Hydroxylation by the [CuO]+ species is predicted to proceed with a smaller activation free energy. The effects of electronic and steric variatons on the oxygenation mechanisms were studied by introducing substituents at several positions of the ligand backbone and by investigating various N-donor ligands. In general, more electron-donation by the N-donor ligand leads to increased stabilization of the more Cu(II)/Cu(III)-like intermediates (oxygen adducts and [CuO]+ species) relative to the more Cu(I)-like peracid intermediate. For all ligands investi-gated, the [CuO]+ intermediates are best described as Cu(II)-O•- species having triplet ground states. The reactivity of these compounds in C-H abstraction reactions decreases with more electron-donating N-donor ligands, which also increase the Cu-O bond strength, although the Cu-O bond is generally predicted to be rather weak (with a bond order of about 0.5). A comparison of several methods to obtain singlet energies for the reaction intermediates indicates that multireference second-order perturbation theory is likely more accurate for the initial oxygen adducts, but not necessarily for subsequent reaction intermediates.

Keywords: oxygen activation, CH bond activation, electronic structure, multiconfigurational quantum chemical methods

Introduction

Copper enzymes that perform catalytic oxidation reactions involving molecular oxygen feature a variety of active site structures and traverse multiple reaction pathways that remain targets of intense study.[1] Among the approaches used in such investigations, the characterization of synthetic copper-oxygen complexes that mimic possible reaction intermediates in the enzymatic processes has been particularly fruitful. For example, detailed structural, spectroscopic, and mechanistic insights have been obtained from extensive studies of systems featuring [Cu2(O2)]2+, [Cu2(μ-O)2]2+, or [CuO2]+ cores.[2]

On the other hand, other proposed reactive intermediates in reactions catalyzed by copper enzymes remain less well characterized – the most notable example being mononuclear copper-oxo species [CuO]+ that can be described as limiting valence bond Cu(III)-oxo or Cu(II)-oxyl complexes. While such species have been suggested as possible intermediates in enzymes such as peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase[3] and in some synthetic systems,[4] to the best of our knowledge they have only been unambiguously identified as reactive species in the gas phase.[5] Initial theoretical investigations[1,5,6] suggest that [CuO]+ systems should be powerful oxidants, similar to or even surpassing the closely related and extensively studied Fe(IV)-oxo complexes.[7]

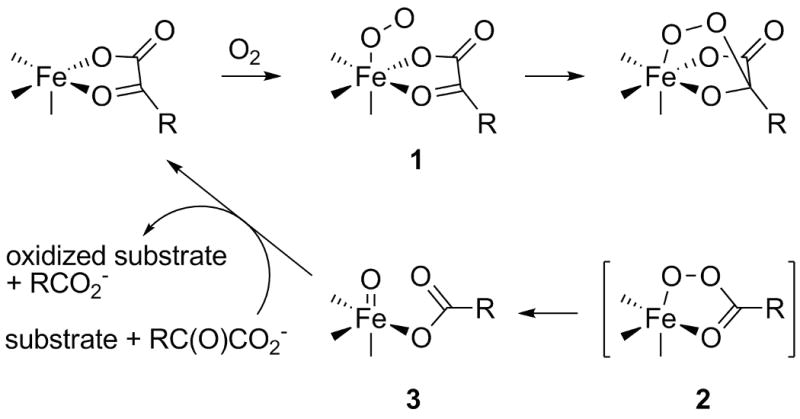

One means for generating the analogous [FeO]2+ functionality is by reaction of molecular oxygen with an Fe(II) α-ketocarboxylate moiety in various enzymes and model complexes.[8] A consensus mechanism for these systems is shown in Scheme 1. After formation of the initial O2 adduct 1, the terminal oxygen atom of the former O2 moiety attacks the α-keto carbon of the ketocarboxylate ligand, resulting in the loss of CO2 and the generation of a peracid intermediate 2. Subsequent O-O cleavage yields the Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate 3 that is widely considered to be the active species in hydrogen atom abstraction reactions from C-H bonds of various substrates.

Scheme 1.

General mechanism for the reactivity of Fe(II)-α-ketocarboxylate sites in enzymes and model complexes.

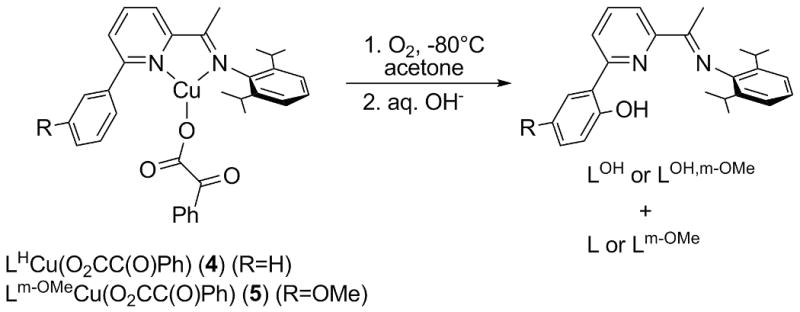

Recently we reported experimental and theoretical results[9] which seem to indicate that a similar reaction can be achieved starting from Cu(I) complexes with α-ketocarboxylate ligands (Scheme 2). In these experiments, the novel Cu(I) α-ketocarboxylate complexes 4 and 5 (amongst others) were reacted with O2 at low temperature. A gradual color change of the solution was observed and after warming and removal of copper under basic conditions, a mixture of the original ligand (L or Lm-OMe) and its hydroxylated form (LOH or LOH,m-OMe) was identified spectroscopically. In addition, a mixture of benzoyl formic acid and benzoic acid was obtained after acidic workup, indicating that partial decarboxylation had taken place (about 40 % for R = H and 60 % for R = OMe). This latter observation, in combination with a more favorable ratio of hydroxylated ligand to original ligand for 5 compared to 4, suggests that the reaction may proceed more efficiently with more electron donating ligands. On the basis of isotope labeling studies and density functional theory (DFT) and multireference second-order perturbation theory (CASSCF/CASPT2) calculations, a mechanism largely analoguous to the Fe(II) case (Scheme 1) was proposed (see below).

Scheme 2.

Oxygenation of Cu(I)-α-ketocarboxylate complexes 4 and 5.

Herein we refine and report further theoretical investigations concerning this reaction mechanism, especially with regard to modifications of the ligand environment around the copper center. In particular, we introduce donor or acceptor substituents into the original ligand framework and examine oxygenation reactions in complexes having different N donor ligands. Furthermore we investigate the influence of those different ligand systems on the electronic nature of the [CuO]+ species and their reactivity in C-H activation and O atom transfer reactions.

Results and Discussion

Fundamental Mechanism

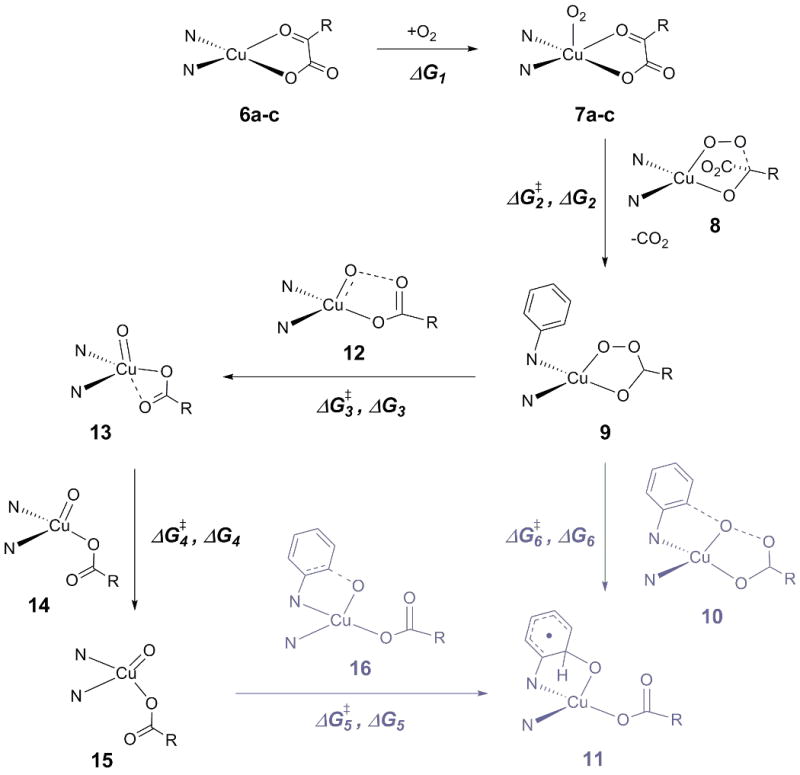

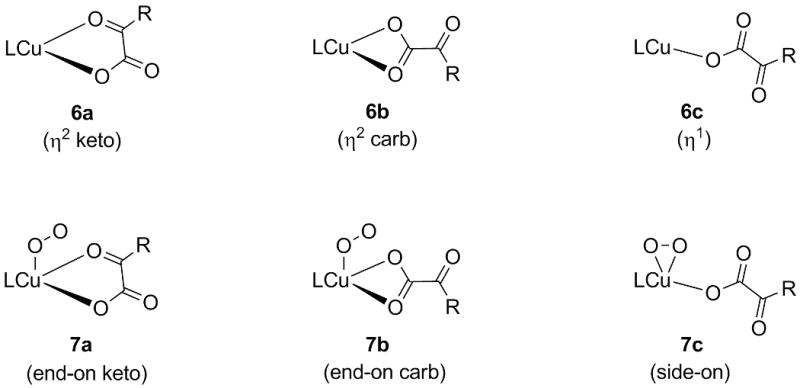

A simplified[10] and slightly revised[11] version of the mechanism we proposed for the oxygenation of 4 (and 5) [9] is presented in Scheme 3 based on a combination of DFT and CASPT2 calculations (detailed descriptions of the theoretical models and a discussion of their relative accuracies are provided in a later section; we use DFT to mean the M06L functional throughout). We considered first ligand L0 (Figure 1), a slightly truncated version of the ligand system used experimentally (cf. Scheme 2). The Cu(I)-α-ketocarboxylate complexes supported by that ligand can exist as three isomers 6a-c (Figure 2), which differ primarily in the mode of coordination of the ketocarboxylate ligand. The most stable isomer 6a (cf. Table 1) features a bidentate ketocarboxylate ligand which is coordinated by one oxygen atom of the carboxylate group and the oxygen atom of the keto group. An isomeric bidentate motif with two coordinating carboxylate oxygen atoms (6b) is 2.5 kcal/mol higher in energy (according to our computations), but still considerably more favorable than the monodentate isomer (6c). As expected, all three species have a singlet ground state. Oxygenation of 6a is roughly ergoneutral and leads to the formation of oxygen adducts 7a-c, which differ in the mode of coordination of the ketocarboxylate ligand and O2 (see Figure 2).

Scheme 3.

Proposed general mechanism for the oxygenation of CuI-α-ketocarboxylate complexes. The N-donor ligand is depicted only schematically. See also Figures 1 and 2, and Tables 1 and 2 for free energies. Structures in gray are only relevant for ligands L0 to L6.

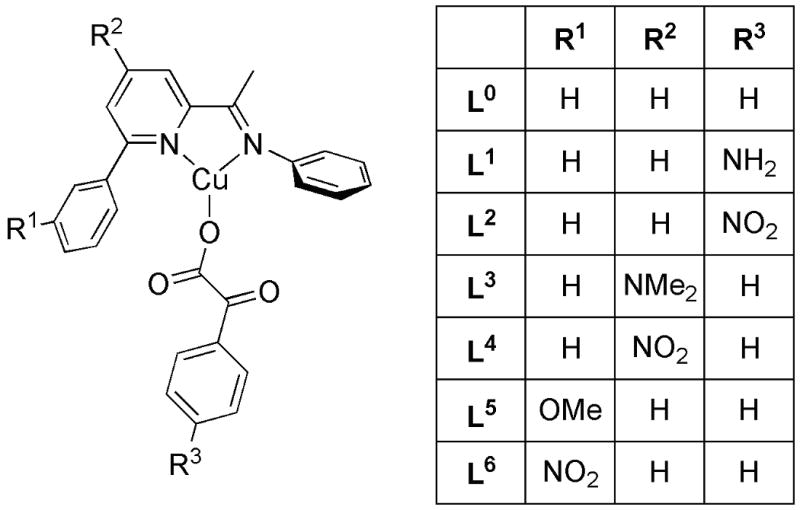

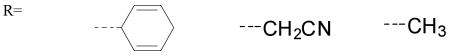

Figure 1.

Model ligand L0, used for evaluation of the mechanism of the oxygenation reaction shown in Scheme 2, and various substituted derivatives L1 to L6, used to study the influence of substitution effects on the individual steps of the mechanism in Scheme 3.

Figure 2.

Isomers of the starting complexes and the oxygen adducts (compare Scheme 3).

Table 1.

Free energies of starting complexes (6a-c) and oxygen adducts (7a-c) in kcal/mol relative to the respective lowest isomer (see Figure 3). Structures of ligands L0 to L6 are shown in Figure 1, those of L7 to L12 in Figure 2. Ground-state multiplicity of oxygen adducts 7a-c in brackets: S = singlet, T = triplet.

| Ligand | 6a | 6b | 6c | 7a | 7b | 7c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 0.0 (T) | 1.2 (T) | 1.5 (T) |

| L1 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 8.3 | 0.0 (T) | 2.7 (T) | 2.0 (T) |

| L2 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 0.2 (T) | 0.0 (T) | 0.2 (T) |

| L3 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 0.0 (T) | 1.2 (T) | 1.1 (T) |

| L4 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 8.1 | 0.0 (T) | 1.8 (T) | 1.0 (T) |

| L5 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 6.6 | 0.0 (T) | 0.8 (T) | 0.0 (T) |

| L6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 7.4 | 0.0 (T) | 2.5 (T) | 2.1 (T) |

| L7 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 8.5 | 0.8 (T) | 0.0 (T) | 4.1[a] |

| L8 | 0.0 | n/a[b] | 0.4 | 0.7 (T) | 1.5 (T) | 0.0 (T) |

| L9 | 0.0 | n/a[b] | 0.7 | 2.9[c] | 1.8 (T) | 0.0 (S) |

| L10 | 0.0 | 1.9 | n/a[b] | 0.5 (T) | 0.0 (T) | 5.4[a] |

| L11 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 (T) | 1.5 (T) | n/a[b] |

| L12 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 (T) | 5.1 (T) | n/a[b] |

no minimum could be located on triplet surface

isomer could not be located

no minimum could be located on the singlet surface

Isomer 7a (featuring the same binding motif of the PhC(O)COO2- moiety as in 6a) is the most stable one, with the other two variants only 1-2 kcal/mol higher in energy. Though one might expect a more Cu(III)-peroxo like character for the side-one isomer 7c (i.e. a singlet ground state),[12] all three isomers are of triplet multiplicity and are thus closer to Cu(II) than to Cu(III).

Decarboxylation of the ketocarboxylate ligand occurs by approach of the terminal oxygen of the O2 ligand to the keto functionality of the former and involves a barrier of about 23 kcal/mol; the reaction step itself is exergonic by more than 40 kcal/mol. Although the decarboxylation transition state 8 still has triplet multiplicity, the resulting peracid structure 9 is a ground-state singlet (and shows no restricted to unrestricted instability at the DFT level).

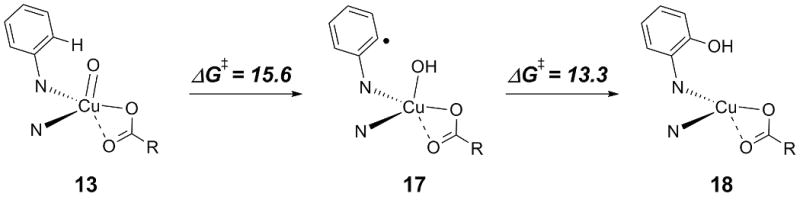

Two pathways leading to the formation of product 11 are found starting from the peracid structure 9. One of them involves direct hydroxylation of a phenyl ring of the N-donor ligand via the transition state 10 (which also has a singlet ground-state) and has a free energy of activation of about 18 kcal/mol (the reaction is exergonic by about 20 kcal/mol). Alternatively, cleavage of the O-O bond via the energetically low-lying transition state 12 yields the [CuO]+ intermediate 13, in which the two N-donor atoms and one carboxylate oxygen occupy the equatorial sites of an overall trigonal-bipyramidal coordination sphere. In order for the oxo oxygen atom to be favorably oriented for the following hydroxylation step, an isomerization must occur. This process again features a relatively low free energy of activation (7 kcal/mol) and results in a square-planar [CuO]+ intermediate 15, in which both N-donor atoms, Cu, and both coordinated O atoms lie in the same plane. Hydroxylation of the ligand phenyl ring by this intermediate via transition state 16 involves an activation free energy of about 6 kcal/mol. The pathway from oxo species 13 to the product 11[13] occurs on the triplet surface. The highest activation free-energy associated with this multistep reaction path is 12 kcal/mol above peracid 9. As direct hydroxylation from the peracid has an activation free energy of 18 kcal/mol, we conclude that the “stepwise” pathway via intermediates 13 and 15 will be the preferred one provided spin-orbit coupling permits efficient crossing from the singlet to triplet surfaces. With a somewhat reduced ligand, we previously computed spin-orbit coupling matrix elements of about 350 cm−1 for TS structures 10 and 12, suggesting that such spin crossing should indeed be reasonably efficient.

Considering for a moment a third possible ring oxidation pathway, we note that the oxo functionality in 13 is quite close to the ortho-position of the phenyl ring that is to be hydroxylated, and may even form a weak hydrogen bond to the hydrogen atom at this position (O-H distance: 2.46 Å). Thus, an alternative hydroxylation mechanism involving H-atom abstraction followed by OH rebound might be envisioned (Scheme 4).[14] However, the activation free energies associated with this process indicate that this pathway is probably not competitive with the “stepwise” hydroxylation in Scheme 3 (for which the activation free energy relative to 13 is only 10.1 kcal/mol).

Scheme 4.

Alternative mechanism for the hydroxylation of the phenyl ring of the N-donor ligand. The N-donor ligand is only depicted schematically. All values in kcal/mol.

Influence of Substituents on Ligand L0

In order to investigate the influence of electronic modifications to the ligand L0 on the reaction mechanism, electron-donating and -withdrawing groups were introduced at different positions on the aromatic rings of either the N-donor ligand or the ketocarboxylate ligand (Figure 1). Our primary focus was the effect of these modifications on the oxygenation thermodynamics and activation barriers for the individual reaction steps.

Introducing a π-electron donating (L1) or -withdrawing (L2) substituent at the para position of the aromatic system of the ketocarboxylate ligand mainly affects the relative energies of the starting complexes and ΔG2‡. Since electron donation increases the donor capacity of the keto oxygen atom, isomer 6a of the starting complexes is favored with respect to the other alternatives, especially the η1 isomer. In addition, the electrophilicity of the keto center is reduced, increasing the decarboxylation barrier by 3 kcal/mol for L1 (cf. the lowering by 3 kcal/mol for L2). Isomer 6a is also stabilized by introducing an electron-withdrawing group on position R2 of the ligand system (L4). The increased electrophilicity of the Cu center disfavors the η1 isomer. By contrast, electron donation at this position (L3) provides more electron density at the Cu center and thus facilitates the oxygenation step. Finally, electronic modification on position R1 yield no pronounced effects on the energetics of the reaction mechanism, as might be expected given the degree to which it is remote from the Cu.

Thus, the decarboxylation step is most influenced by substituents at R3, while modifications at R2 mainly effect the oxygenation step. The experimental observation that electron donors at position R1 slightly improve the overall product yield cannot be rationalized based on these calculations and are thus assumed to derive from other, non-electronic reasons (as the experiments are far from achieving 100% mass balance, we do not speculate further on this point). The steps following decarboxylation are not particularly sensitive to ligand substitution, except that compared to the other ligands the electron-withdrawing nitro group in L4 destabilizes all species relative to peracid 9 by 3 to 6 kcal/mol, consistent with 9 having the lowest oxidation state (Cu(I)) of all of these species.

Influence of Changes in N-Donor Ligand Structure

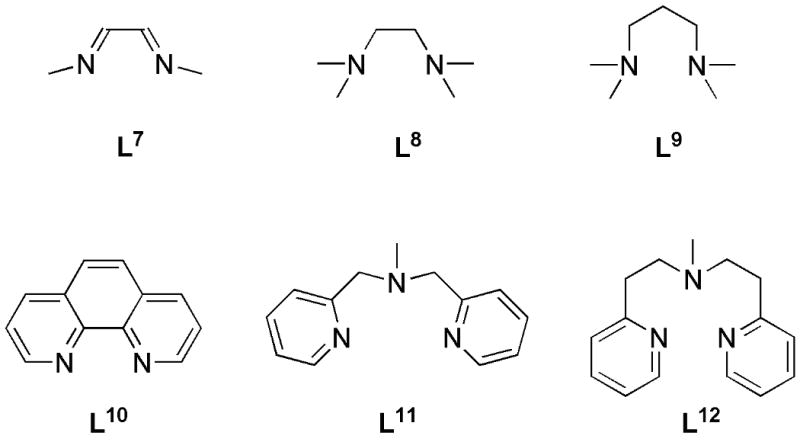

One might expect that broader variations of electronic and steric effects could be achieved with N-donor ligands having backbones fundamentally different from that in L0 to L6. To investigate this point, we chose a number of typical N-donor ligands (L7 to L12, Figure 3) with which to model the corresponding reactions of Scheme 5.

Figure 3.

N-donor ligands L1 to L12 used to investigate ligand effects on the oxygenation reaction of Scheme 3.

Scheme 5.

Model reactions to study the C-H activation reactivity and the strength of the Cu-O bond (see also Table 4). The energetically lowest copper oxo isomer was used for each respective ligand.

In contrast to L0 (and its substituted variants), none of these ligands possesses a phenyl ring that can be hydroxylated by the oxo intermediate, so we consider only those steps up to the generation and possible isomerization of that reactive intermediate. Indeed, we are particularly interested in the degree to which we might be able to design a ligand or ligands for which oxo intermediates would be the lowest-energy points along the reaction coordinates, since such species might then be accessible experimentally. There is also the interesting question of whether the decarboxylation reaction proceeds via a peracid intermediate in all cases, or whether O–O bond cleavage might occur concomitantly with loss of CO2.

Comparing L7 to L0, the isomer energies for the various pre- and post-O2 adducts are similar, as might be expected given the similar electronic nature of the two ligands (featuring two sp2-N donors). The other such N-donor ligand, L10, features less distinction between the η2 isomers 6a and 6b and, despite several attempts, an η1 isomer could not be located. With increasing donor strength of the supporting ligand (L8, L9, L11, and L12), the η1 isomer 6c becomes more favorable and the different isomers are almost isoenergetic. Apparently the electronic demand of the Cu center is effectively saturated by the two (or three) N donors and one O donor in these cases. For L11 and L12, the donor strength of the third N center seems to be just as good as that of a second O donor. As indicated in Table 1, not all isomers could be found for all ligand systems. Since the N- and O-donors are similar in strength, this might at least partly be due to steric hindrance.

The energetic differences between the three oxygen adduct isomers 7a-c are generally also quite small. For the less donating L7 and L10, the side-on isomer 7c is somewhat less competitive, since the more electrophilic Cu center is less readily oxidized to a more Cu(III)-peroxo-like side-on isomer. In contrast, the stronger donor ligands L8 and L9 tend to favor the side-on isomer. From an electronic point of view, the same might be true for L11 and L12, but in these cases steric hindrance prohibits the formation of a side-on adduct. For all ligands, the end-on isomers 7a and 7b are ground-state triplets. Despite various attempts, no triplet side-on minimum could be found in the cases of L7 and L10. L9, a strong N-donor ligand, seems to induce a more Cu(III) like character of the side-on isomer, which consequently possesses a singlet ground state.[12]

With respect to the remaining steps in the oxo-generating mechanism, ligand L7 shows comparable energetics to the parent ligand L0, at least until the [CuO]+ isomerization. In contrast to all other ligand systems, the singlet peracid structure 9 shows a very slight[15] restricted to unrestricted singlet instability in this case. This appears to render it non-stationary, as no O-O cleavage transition state 12 could be located on the singlet surface for this case; a corresponding triplet TS structure was found, leading directly to formation of the square-planar [CuO]+ isomer 15. Unlike L0, the latter is isoenergetic to the trigonal-bipyramidal variant 13, which might be due to lesser steric hindrance in the simple bis(imine) ligand L7 (compared to the bulky L0), especially with regard to the N-Cu-N plane.

With the more donating ligand L8, the oxygenation step becomes exergonic, in agreement with the trends observed for the substituted versions of L0. Decarboxylation via transition state 8 occurs on the singlet surface and yields peracid 9 (the triplet TS structure is 1.9 kcal/mol higher in energy and yields oxo species 15 directly). Generation of the [CuO]+ isomers is more favorable than with L7, and the trigonal-bipyramidal isomer 13 is slightly preferred over the square-planar form 15.

Most of the trends observed when comparing L8 to L7 are quantitatively enhanced for the still more strongly donating ligand L9, e.g., exergonicity of oxygenation, preference for a singlet decarboxylation TS structure, and stability of the oxo species. In this case, however, the energetically less favorable (1.4 kcal/mol) triplet decarboxylation TS structure leads to the trigonal-bipyramidal oxo species 13. Likely owing primarily to the increase in ligand bite angle, the energetic preference for 13 relative to 15 is markedly enhanced with L9 compared to L8.

Although from an electronic point of view, ligand L10 might seem comparable to ligands L0 and L7 (two sp2 N-donor atoms), its influence on the oxygenation mechanism is different from the other two ligands in several respects. The oxygenation step itself is more exergonic than with the bis(sp3) N-donor ligand L8. Decarboxylation occurs via a singlet TS structure, but leads directly to the square-planar [CuO]+ intermediate 15 without proceeding via peracid intermediate 9. In this case, it is the energetically unfavorable (1.1 kcal/mol) triplet TS structure that yields a peracid intermediate. Ligand L10 also shifts the preference between the [CuO]+ intermediates back towards the square-planar variant 15, and indeed it is the only ligand for which this geometry is lower in energy than isomeric 13. It is evident from comparison of these ligands that those regions of the singlet and triplet potential energy surfaces in the vicinity of their respective decarboxylation TS structure(s) must be fairly flat between competing reaction channels.

Ligand L11 and L12 differ from those discussed above insofar as they are tridentate N-donor ligands. However, their oxygenation mechanisms resemble reasonably closely those of the strong N-donor ligands L8 and L9. For L11, we considered whether decoordination of one pyridine N donor might reduce the energy of the decarboxylation transition state, but the resulting TS structure is about 7 kcal/mol higher in energy than the fully coordinated alternative. The peracid itself in the case of L11 leads very readily (0.9 kcal/mol activation barrier) to 13, suggesting that the tridentate ligand is very effective in stabilizing the Cu(II)/Cu(III) oxidation state in this product relative to the Cu(I) peracid educt. However, in the case of L12, the decarboxylation on the triplet surface leads directly to the formation of 15 while the higher-energy decarboxylation TS structure on the singlet surface produces the Cu(I) peracid educt. The transition state structure from the Cu(I) peracid educt to 13 could not be located on the singlet surface and the barrier on the triplet surface is relatively high (34.8 kcal/mol).

In summary, details of the oxygenation of the copper complexes supported by the various N-donor ligands are only modestly sensitive to ligand structure. More interestingly, the [CuO]+ intermediates 13 and 15 are predicted to be energetic minima in all cases and should thus be accesible for a variety of N-donor ligands. With the exception of one ligand (L10), the peracid structure 9 always occurs as an intermediate product of the decarboxylation step. The group of ligands L7 to L9 illustrate the degree to which more electron-rich Cu centers facilitate initial oxygenation. In addition, the decarboxylation step becomes less exergonic, while [CuO]+ generation becomes more favorable. These trends are consistent with the change of oxidation state of the central Cu atom, from Cu(II)/Cu(III) in the oxygen adducts to Cu(I) in the peracid structure and back to Cu(II)/Cu(III) in the oxo species (see below). In the absence of significant steric constraints in the ligand, the trigonal-bipyramidal oxo isomer 13 is preferred over the square-planar isomer 15.

Electronic Structure of [CuO]+ Intermediates

Species 13 (and 15) may be described by two alternative, limiting, electronic valence bond structures, namely, a (singlet) copper(III)-oxo structure or a (triplet) copper(II)-oxyl species. As has been reported before[1d,5] for related systems, we predict the latter variant to be the more accurate for [CuO]+ complexes. Apart from the triplet ground state of 13 and 15 (for all ligands investigated), this is also evident from orbital analyses and NBO[16] calculations. For instance, in the case of L0 one SOMO is identical with an O p-orbital, while the other SOMO is mainly located on a Cu 3d-orbital (mixed with ligand p-orbitals). An NBO analysis confirms this view by localizing approximately 9 d-electrons on Cu and 5 electrons assigned as “lone pair” types on O. NBO analysis thus considers the Cu-O bond to have only a σ component, the covalency of which may be quantified by its relatively low Wiberg bond order of 0.4. Similar bond orders were obtained for ligand systems L7 to L12, indicating a consistently weak Cu-O bond. Within the series of ligands investigated, only slight variations in several key parameters of the Cu-O core were observed (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Selected parameters for trigonal-bipyramidal species 13 with different N-donor ligands. Bond lengths in Å, energies in kcal/mol, charge and spin in a.u.

| Ligand | d (Cu-O) | S-T[a] | Charge on Cu[b] | Charge on O[b] | Spin on Cu[c] | Spin on O[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L0 | 1.806 | 7.2 | 1.23 | -0.63 | 0.53 | 1.23 |

| L7 | 1.802 | 5.9 | 1.23 | -0.62 | 0.53 | 1.22 |

| L8 | 1.806 | 6.2 | 1.25 | -0.65 | 0.55 | 1.19 |

| L9 | 1.811 | 6.3 | 1.26 | -0.67 | 0.56 | 1.17 |

| L10 | 1.800 | 8.5 | 1.22 | -0.62 | 0.54 | 1.23 |

| L11 | 1.804 | 6.9 | 1.27 | -0.65 | 0.58 | 1.21 |

| L12 | 1.809 | 1.6 | 1.25 | -0.66 | 0.52 | 1.18 |

Singlet-triplet state-energy differences.

NBO charges

Mulliken spin densities.

Although the differences are small, they do exhibit a trend, with more electron-donating ligands resulting in a) longer Cu-O bonds, b) smaller singlet/triplet splittings (from increased stabilization of the Cu(III)-oxo singlet), c) less spin localization on O (but more on Cu), and d) more electronic charge on O.

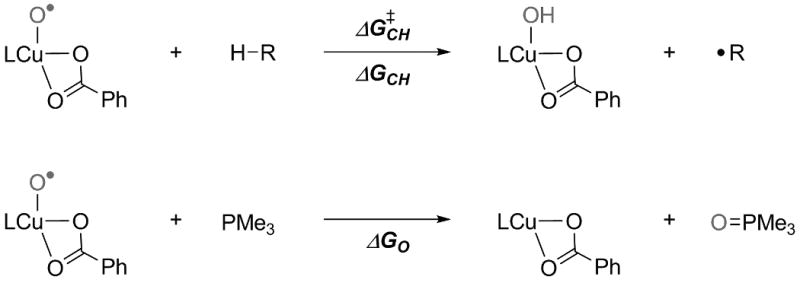

In order to investigate the relevance of these trends on the “chemical behaviour” of the various oxo species, the model reactions depicted in Scheme 5 were considered. For the C-H abstraction reaction (Scheme 5 top), the three substrates 1,4-cyclohexadiene (ΔGdissC-H = 305 kcal/mol),[17] acetonitrile (ΔGdissC-H = 393 kcal/mol)[18] and methane (ΔGdissC-H = 439 kcal/mol)[18] with the C-H bond strengths indicated were used.

The activation and reaction free energies presented in Table 4 indicate that [CuO]+ complexes with more electron-donating ligands (L9, L11) are less reactive in C-H abstraction reactions compared to complexes with less donating ligands (L0, L10). Based on these calculations, species 15 with the weak N-donor ligand L10 is the most reactive, leading to an almost ergoneutral reaction with methane.

Table 4.

Activation and reaction free energies (kcal/mol) for the reactions shown in Scheme 5.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | ΔG‡CH | ΔGCH | ΔG‡CH | ΔGCH | ΔG‡CH | ΔGCH | ΔGO |

| L0 | 5.7 | -30.5 | 8.8 | -8.4 | 17.3 | 2.6 | -77.2 |

| L7 | 7.5 | -30.0 | 9.8 | -8.0 | 17.7 | 3.0 | -77.7 |

| L8 | 7.1 | -30.5 | 9.9 | -8.4 | 17.8 | 2.6 | -70.5 |

| L9 | 7.1 | -29.6 | 9.2 | -7.5 | 17.6 | 3.5 | -62.8 |

| L10 | 5.0 | -32.4 | 8.4 | -10.4 | 15.3 | 0.6 | -74.9 |

| L11 | 8.3 | -27.6 | 9.4 | -5.5 | 19.5 | 5.5 | -67.5 |

| L12 | 7.0 | -30.2 | 10.9 | -8.2 | 18.3 | 2.8 | -72.2 |

These findings are consistent with the trends evident in Table 3, where more electron-donating ligands lead to slightly less O-radical character in the [CuO]+ species 13 in favor of more basic Cu(III)-oxo character. Overall, of course, the differences between the various ligands are rather small, with all [CuO]+ species being very reactive, which highlights the experimental challenges that will be associated with isolation of a stable supported [CuO]+ moiety.

The weak nature of the Cu-O bond in 13, as evidenced from the NBO analyses, is reflected in the very exergonic reaction free energies predicted for oxygen atom transfer to trimethylphosphine (Table 4, last row). Following the reasoning already presented above, more electron-donating ligands will lead to increased bond orders associated with Cu(III)-oxo valence-bond character and reduce the transfer free energy. Such behavior is indeed observed, e.g., comparing the ΔGO values for L7 to L9, where the former complex is more reactive by 15 kcal/mol.

It is evident that stable [CuO]+ functionality will be difficult to achieve without substantial isolation of the species from internal and external reactive partners. Further experimental investigations in this direction are underway.

Spin-State Energies as a Function of Theoretical Protocol

With the exception of the starting complexes 6a-c and the peracid structures 9, the Kohn-Sham (KS) determinants for all other stationary points are characterized by restricted to unrestricted instabilities at the DFT level. Expectation values of the total spin operator S2 over unrestricted broken-symmetry (BS) singlet solutions in most instances were near 1.0, suggesting roughly equal weights of singlet and triplet spin states in the determinant (high-spin triplet KS determinants showed negligible spin contamination in all instances).

As described in more detail in the computational methods section, we considered 3 different approaches to estimate the energies of singlet species compared to their triplet analogs, assuming the latter to be well described by high-spin Kohn-Sham DFT calculations. In the first model, we simply took the BS energy to be the singlet state energy, ignoring the value of <S2>. In the second model, we used the sum method to purify the BS energy of its triplet component.[19] In the third and last model, we computed the difference in energy between the singlet and triplet spin states at the CASSCF/CASPT2 level[20] and added this to the high-spin triplet energy of the optimized BS DFT geometry. This model effectively assumes that (i) the BS DFT geometry is a good approximation to the true singlet geometry, (ii) the high-spin triplet energy of this geometry relative to the optimized triplet minimum will be accurately determined at the DFT level, and (iii) the multiconfigurational CASSCF/CASPT2 model will predict singlet-triplet state-energy splittings with similar accuracy.

As an example, we may consider molecular oxygen as a test case. The diatomic O2 has a triplet ground state and a 1Δg state 22.6 kcal/mol higher in energy.[21] As expected, BS DFT calculations for the singlet state lead to a KS determinant with <S2> = 1. Using the three protocols outlined above, and a full-valence active space for the CASSCF/CASPT2 model, we predict S-T splittings for O2 of 14.9, 29.1, and 24.0 kcal/mol, respectively. It is evident that the hybrid DFT-CASSCF/CASPT2 approach provides the best results in comparison with experiment. This test represents a worst-case scenario for the KS DFT model, since the proper 1Δg wave function requires at a minimum two equally weighted determinants. Thus, while spin purification improves upon the uncorrect BS prediction, the error still remains relatively large. In the discussion above, we refer exclusively to singlet energies computed according to protocol (iii), but it is of technical interest to examine the performance of the three different protocols for the various structures that were surveyed, in order to assess their relative utility in different circumstances.

Thus, Table 5 provides singlet-triplet electronic energy splittings at the uncorrected BS DFT (ΔEuncorr), spin-purified (ΔEcorr), and CASSCF/CASPT2 (ΔECAS) levels for all BS DFT structures showing spin contamination on the singlet surface with ligands L0 and L7 to L12. Table 5 also lists the high-spin triplet DFT energy difference between the optimized triplet and BS singlet geometries (ΔET), in this case including thermal contributions computed at the DFT level for the respective optimized geometries/states. Thus, our best estimate of the “proper” singlet-triplet splitting can be obtained by summing ΔET with ΔECAS.

Table 5.

Singlet-triplet energy splittings (kcal/mol) from different theoretical models.

| 7a | 7b | 7c | 8 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L0 | ΔET | 1.8 | 1.1 | 7.1 | 1.3 | -10.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| ΔECAS | 3.2 | 2.2 | -4.1 | -0.2 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 4.8 | |

| ΔEcorr | 21.4 | 21.5 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 7.7 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 10.6 | 10.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.9 | |

| L7 | ΔET | 3.1 | 2.0 | n/a | 2.2 | n/a | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| ΔECAS | 2.3 | 1.2 | n/a | -0.3 | n/a | 5.2 | 8.4 | 6.0 | |

| ΔEcorr | 13.6 | 12.7 | n/a | -4.9 | n/a | 8.7 | 7.2 | 7.4 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 6.7 | 6.3 | n/a | -3.1 | n/a | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| L8 | ΔET | 4.3 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 1.1 | n/a | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| ΔECAS | 0.3 | -0.1 | 4.6 | -3.5 | n/a | 5.8 | 7.2 | 3.8 | |

| ΔEcorr | 10.4 | 13.6 | 8.2 | -3.1 | n/a | 7.7 | 8.9 | 7.3 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 5.2 | 6.8 | 4.1 | -1.8 | n/a | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.6 | |

| L9 | ΔET | 1.6 | 1.8 | 7.8 | 2.6 | n/a | 1.3 | -0.3 | 0.9 |

| ΔECAS | 0.4 | 0.7 | -10.3 | -4.3 | n/a | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.8 | |

| ΔEcorr | 18.0 | 11.7 | 2.1 | -4.8 | n/a | 7.4 | 15.9 | 9.6 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 10.0 | 5.8 | 1.7 | -3.0 | n/a | 3.7 | 7.9 | 4.8 | |

| L10 | ΔET | 6.8 | 2.0 | n/a | 3.6 | n/a | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| ΔECAS | 1.1 | 8.0 | n/a | -4.7 | n/a | 5.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | |

| ΔEcorr | 2.0 | 11.6 | n/a | -6.7 | n/a | 6.2 | 9.9 | 8.7 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 1.0 | 5.8 | n/a | -4.8 | n/a | 3.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 | |

| L11 | ΔET | 1.3 | 1.7 | n/a | 0.3 | -13.1 | 1.9 | n/a | 2.1 |

| ΔECAS | 2.1 | 2.5 | n/a | -14.4 | -9.7 | 5.2 | n/a | 2.4 | |

| ΔEcorr | 11.8 | 12.0 | n/a | -2.1 | -9.2 | 7.1 | n/a | 7.4 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 5.9 | 6.0 | n/a | -1.4 | -7.9 | 3.6 | n/a | 3.9 | |

| L12 | ΔET | 1.7 | 5.6 | n/a | 2.5 | n/a | 2.6 | n/a | 1.5 |

| ΔECAS | 2.1 | 0.9 | n/a | -2.4 | n/a | -1.0 | n/a | -1.0 | |

| ΔEcorr | 12.8 | 5.9 | n/a | -3.3 | n/a | 5.1 | n/a | 7.4 | |

| ΔEuncorr | 2.9 | 6.4 | n/a | -1.9 | n/a | 2.6 | n/a | 3.8 | |

It is apparent that the DFT predictions vary most from the CASSCF/CASPT2 predictions for the oxygen adducts 7a-c. Over all structures 7, the mean unsigned error (MUE) between uncorrected DFT and CASSCF/CASPT2 is 4.8 kcal/mol; the MUE for purified DFT is 9.5 kcal/mol. Evidently, the biradical character of these complexes is significant and thus similar to molecular oxygen to the extent that large DFT protocol errors are observed. This suggests a formal Cu(II)/superoxide character with substantially separated spins which leads to small splittings predicted at the CASSCF/CASPT2 level but significant errors at the DFT level owing to the very multideterminantal character of the singlet state. For 8 and the following reaction intermediates, on the other hand, the three protocols provide more similar estimates, especially after cleavage of the O-O bond. In particular, the mean unsigned error (MUE) between uncorrected DFT and CASSCF/CASPT2 is 2.5 kcal/mol, and the MUE for purified DFT is 3.7 kcal/mol. These values are within a conservative error estimate on the CASSCF/CASPT2 predictions. Thus, we conclude that for reaction intermediates other than 7 DFT calculations either with or without spin purification may provide reasonable estimates of singlet-triplet energy separations. Because of the greater rigor of the CASSCF/CASPT2 model, it is certainly to be preferred in those instances where it may be conveniently applied. However, the DFT approach may be a useful approximation in those cases where application of the CASSCF/CASPT2 model is not straightforward, e.g., because of uncertainties in active space construction or size limitations. Moreover, comparison between the multiconfigurational and DFT models can be particularly helpful for identifying erroneous predictions that might otherwise not be obvious; this proved true in several instances during the course of the present investigation.

Conclusion

We have detailed mechanisms for the oxygenation and subsequent reaction of Cu(I) complexes with α-ketocarboxylate ligands that is based on a combination of density functional theory and multireference second-order perturbation theory (CASSCF/CASPT2) calculations. Our findings suggest that the reaction proceeds in a fashion largely analogous to that of similar Fe(II) α-ketocarboxylate systems, i.e., by initial attack of coordinated oxygen on the ketocarboxylate ligand and concomitant decarboxylation. Subsequently, two reactive intermediates can be generated, a peracid structure 9 and a [CuO]+ species 15 (as well as its isomer 13), both of which are capable of oxidizing a phenyl moiety attached to the ligand backbone. Hydroxylation by the latter [CuO]+ species is predicted to be energetically more favorable.

The effect of electronic and steric variatons on the oxygenation mechanism were studied by introducing substituents at several positions of the ligand backbone and by investigating several other N-donor ligands. In general, more electron-donation by the N-donor ligand leads to stabilization of the more Cu(II)/Cu(III)-like intermediates (oxygen adducts, [CuO]+ species) relative to the more Cu(I)-like peracid intermediate.

For all ligands investigated, the [CuO]+ intermediates are best described as Cu(II)-oxyl species with triplet ground states. The reactivity of these compounds in C-H abstraction reactions decreases with more electron-donating N-donor ligands. The latter also increase the Cu-O bond strength, although the Cu-O bond is generally predicted to be very weak (with a bond order of about 0.5). A comparison of several methods to obtain singlet energies for the reaction intermediates indicates that multireference second-order perturbation theory methods are more accurate than DFT for initial oxygen adducts 7a-c, but not necessarily for the further reaction intermediates.

In short, our results suggest that the generation of [CuO]+ intermediates like 13 and 15 should be feasible for Cu(I) α-ketocarboxylate complexes with a variety of N-donor ligands. These species are, however, predicted to be very reactive, posing some challenges to their experimental isolation.

Computational Methods

All geometries were fully optimized at the M06L level of density functional theory[22] using the Stuttgart pseudopotential basis set on Cu[23] (including three f functions having exponents of 5.10, 1.275, and 0.32) and the 6-31G(d) basis set[24] on all other atoms. All singlet geometries other than those for the peracid complex and the starting complexes were obtained using broken-spin-symmetry calculations; the peracid was predicted to have a stable restricted Kohn-Sham wave function. The nature of all stationary points was verified by analytic computation of vibrational frequencies, which were also used for the computation of molecular partition functions (with all frequencies below 50 cm−1 replaced by 50 cm−1 when computing free energies) and for determining the reactants and products associated with each transition-state structure (by following the normal modes associated with imaginary frequencies). In order to correct for biradical character in some of the singlet structures, multireference second-order perturbation theory (CASSCF/CASPT2)[21] computations were also performed. Singlet energies were computed by taking M06L triplet energies and adjusting them by singlet-triplet splittings computed at the CASSCF/CASPT2 level for structures otherwise identical to broken-symmetry singlets computed at the M06L level (also referred to as protocol iii in the discussion). The CASSCF/CASPT2 method has proven to be successful in the study of many analogous transition metal problems.[25]

The CASSCF/CASPT2 calculations employed the ANO-RCC basis set of Roos and co-workers[26], with a 5s3p2d1f contraction for Cu, 3s2p1d for heteroatoms, 3s2p for carbon, and 2s for hydrogen. To expedite the calculations, we used the Cholesky decomposition (CD) approximation to the two-electron integrals[27,28] in combination with the local exchange (LK) algorithm.[29] Based on previous analysis of the accuracy of the CD approximation,[30] a decomposition threshold of 10-6 was chosen for all CASSCF/CASPT2 calculations.

The typical active space for all ligand-systems included the 3d orbitals on Cu and two orbitals of the initial O2 moiety involved in the bond rearrangements. To better account for dynamical correlation effects, the 4d orbitals of Cu were also included, giving rise to a final (12 in 12) active space. In many cases, and especially to facilitate the choice of the 4d orbitals, Cholesky localization[31] was performed on the initial molecular orbitals prior to CASSCF calculations.

For singlet state DFT calculations, restricted self-consistent-field solutions were obtained first, and then checked for restricted to unrestricted instabilities. When such instabilities were found, the Kohn-Sham wave functions were reoptimized with an unrestricted formalism. Spin purification involved the elimination of triplet-state spin contamination from broken-spin-symmetry Kohn-Sham determinants. Thus, the singlet energy is computed as[19]

| (1) |

where the triplet energy is computed for the single-determinantal high-spin configuration Sz=1 (at the UDFT level) and <S2> is the expectation value of the total-spin operator applied to the Kohn-Sham determinant for the unrestricted broken-symmetry calculation.

All DFT computations were performed with MN-GFM,[32] a locally modified version of Gaussian 03.[33] All CASSCF/CASPT2 calculations were performed with MOLCAS 7.0.[34]

Table 2.

Free energies (kcal/mol) relative to lowest isomer of 6a-c and O2 (left side) or peracid 9 (right side). Selected free energy changes in parentheses. See also Scheme 3. For species 8 to 16, ground-state singlets are indicated by values in italics (starting complexes 6 are generally singlets, for multiplicity of 7a-c for various ligands see Table 2).

| Ligand | 6[a] + O2 | 7[a] | 8 (ΔG2‡) | 9 + CO2 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 (ΔG4‡) | 15 (ΔG4) | 16 (ΔG5‡) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 23.3 (22.8) | -41.8 | 0.0 | 17.8 | -19.9 | 12.4 | -11.3 | -4.5 (6.8) | -6.9 (4.5) | -1.2 (5.6) |

| L1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 26.6 (26.0) | -40.1 | 0.0 | 18.7 | -24.1 | 13.4 | -11.2 | -3.7 (7.5) | -5.9 (5.3) | -0.3 (5.6) |

| L2 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 21.2 (19.9) | -42.3 | 0.0 | 17.2 | -26.5 | 16.4[c] | -11.5 | -5.3 (6.2) | -8.1 (3.4) | -2.7 (5.4) |

| L3 | 0.0 | -0.8 | 21.9 (22.7) | -41.7 | 0.0 | 17.4 | -26.4 | 12.8 | -12.3 | -6.7 (5.6) | -8.9 (3.4) | -3.1 (5.8) |

| L4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 25.1 (22.9) | -43.5 | 0.0 | 20.4 | -17.4 | 13.8 | -8.3 | -0.7 (7.6) | -2.8 (5.5) | 2.3 (5.1) |

| L5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 23.2 (22.9) | -42.8 | 0.0 | 18.0 | -21.4 | 15.7[c] | -11.5 | -3.6 (7.9) | -5.9 (5.6) | -0.6 (5.3) |

| L6 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 23.9 (24.0) | -42.7 | 0.0 | 18.2 | -25.3 | 16.2[c] | -11.7 | -3.3 (8.4) | -5.3 (6.4) | -1.9 (3.4) |

| L7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 19.3 (18.2) | -45.3 | 0.0 | --- | --- | 12.0[c] | -7.7 | -6.0 (1.7) | -7.6 (0.1) | --- |

| L8 | 0.0 | -2.1 | 12.7[d] (14.8) | -44.3 | 0.0 | --- | --- | 7.0 | -15.8 | -13.9 (1.9) | -14.9 (0.9) | --- |

| L9 | 0.0 | -11.3 | 8.2[e] (19.5) | -43.7 | 0.0 | --- | --- | 8.1 | -25.4 | -16.8 (8.6) | -17.6 (7.8) | --- |

| L10 | 0.0 | -4.1 | 13.6[f] (17.6) | -44.4[f] | 0.0 | --- | --- | [f] | -12.4 | -11.5 (0.9) | -13.6 (-1.2) | --- |

| L11 | 0.0 | -8.9 | 6.9 (15.8) | -41.6 | 0.0 | --- | --- | 0.9 | -21.4 | [b] | -17.1 (4.4) | --- |

| L12 | 0.0 | -6.0 | 7.6 (13.6) | -48.1[g] | 0.0 | --- | --- | 34.8[c] | -15.2 | [b] | -8.9 (6.3) | --- |

Lowest-energy isomer.

No transition-state (TS) structure could be located.

No TS structure could be located on the singlet surface; energy refers to triplet TS structure leading directly to 15.

Analogous higher energy TS structure on triplet surface leads directly to 15.

Analogous higher energy TS structure on triplet surface leads directly to 13.

The lowest-energy decarboxylation TS structure is found on the singlet surface and leads directly to 15; only a triplet peracid intermediate is stationary.

Analogous lower energy TS structure on triplet surface leads directly to 15.

Acknowledgments

S.M.H thanks the DAAD for a postdoctoral scholarship. For financial support, F.A., S.M.H., and L.G. acknowledge the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant n. 200020-120007), WBT thanks the U.S. NIH (GM47365) and C.J.C. thanks the U.S. NSF (CHE06-10183).

Contributor Information

Prof. Laura Gagliardi, Email: Laura.Gagliardi@chiphy.unige.ch.

Prof. Dr. William B. Tolman, Email: wtolman@umn.edu.

Prof. Dr. Christopher J. Cramer, Email: cramer@umn.edu.

References

- 1.a) Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Solomon EI, Chen P, Metz M, Lee SK, Palmer AE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4570–4590. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4570::aid-anie4570>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Klinman JP. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2541–2561. doi: 10.1021/cr950047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Decker A, Solomon EI. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Solomon EI, Sarangi R, Woertink J, Augustine A, Yoon J, Ghosh S. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:581–591. doi: 10.1021/ar600060t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selected recent reviews: Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z.Lewis EA, Tolman WB. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r.Hatcher L, Karlin KD. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:669–683. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0578-4.Itoh S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.012.Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:601–608. doi: 10.1021/ar700008c.Suzuki M. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:609–617. doi: 10.1021/ar600048g.Gherman BF, Cramer CJ. Coord Chem Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.018. in press.

- 3.a) Crespo A, Marti MA, Roitberg AE, Amzel LM, Estrin DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12817–12828. doi: 10.1021/ja062876x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kmachi T, Kihara N, Shiota Y, Yoshizawa K. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4226–4236. doi: 10.1021/ic048477p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yoshizawa K, Kihara N, Kamachi T, Shiota Y. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:3034–3041. doi: 10.1021/ic0521168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Evans JP, Ahn K, Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49691–49698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chen P, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4991–5000. doi: 10.1021/ja031564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3013–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For examples, see: Kitajima N, Koda T, Iwata Y, Moro-oka Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8833–8839.Capdevielle P, Sparfel D, Baranne-Lafont J, Cuong NK, Maumy M. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1990:565–566.Reinaud O, Chapdevielle P, Maumy M. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1990:566–568.Maiti D, Lucas HR, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6998–6999. doi: 10.1021/ja071704c.Maiti D, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:8736–8747. doi: 10.1021/ic800617m.

- 5.Schroeder D, Holtzhausen MC, Schwarz H. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:14407–14416. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gherman BF, Tolman WB, Cramer CJ. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1950–1961. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For example, see: Que L., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ar700024g.Krebs C, Galonic DF, Fujimori D, Walsh C, Bollinger J. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:484–492. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p.Nam W. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:522–531. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f.Shaik S, Hirao H, Kumar D. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:532–542. doi: 10.1021/ar600042c.Schroder D, Shaik S, Schwarz H. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:139–145. doi: 10.1021/ar990028j.Shaik S, Kumar D, deVisser SP, Altun A, Thiel W. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2279–2328. doi: 10.1021/cr030722j.Harvey JN, Poli R, Smith KM. Coord Chem Rev. 2003;238-239:347–361.Anastasi AE, Comba P, McGrady J, Lienke A, Rohwer H. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:6420–6426. doi: 10.1021/ic700429x.Bautz J, Comba P, de Laorden CL, Menzel M, Rajaraman G. Angew Chem In Ed. 2007;46:8067–8070. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701681.Kryatov SV, Rybak-Akimova EV, Schindler S. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2175–2226. doi: 10.1021/cr030709z.

- 8.a) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Abu-Omar MM, Loaiza A, Hontzeas N. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2227–2252. doi: 10.1021/cr040653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Borowski T, Bassan A, Siegbahn PEM. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:3277–3291. doi: 10.1021/ic035395c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Bassan A, Borowski T, Siegbahn PEM. Dalton Trans. 2004:3153–3162. doi: 10.1039/B408340G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong S, Huber SM, Gagliardi L, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14190–14192. doi: 10.1021/ja0760426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.When approaching the terminal oxygen atom of the O2 ligand to the keto carbon atom of the ketocarboxylate ligand, a minimum (featuring an O-C distance just below the sum of the van-der-Waals radii) was found prior to the decarboxylation transition state. Since this minimum is more than 10 kcal/mol higher in energy than the lowest O2 adduct and does not seem to play any relevant role in the reaction mechanism, it will be omitted in all further discussion.

- 11.Our initial findings with a more truncated ligand model and using a smaller basis set in multireference calculations suggested that cleavage of the O-O bond of the peracid intermediate would occur via a triplet transition state and lead to the square-planar oxo intermediate. The improved calculations here indicate that this cleavage likely occurs at somewhat lower energy on the singlet surface and results in direct formation of the trigonal-bipyramidal oxo intermediate.

- 12.Cramer CJ, Gour JR, Kinal A, Wloch M, Piecuch P, Moughal Shahi AR, Gagliardi L. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:3754. doi: 10.1021/jp800627e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The radical character of the substituted phenyl ring in the immediate hydroxylation product 11 is in agreement with earlier computations on a related Fe system: see [8a].

- 14.Comba P, Knoppe S, Martin B, Rajaraman G, Rolli C, Shapiro B, Stork T. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:344–357. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The <S2> value for the singlet peracid structure 9 is 0.11 in the case of ligand L7.

- 16.Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chem Rev. 1988;88:899. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griller D, Wayner DDM. Pure Appl Chem. 1989;61:717. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkowitz J, Ellison GB, Gutman D. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:2744. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Ziegler T, Rauk A, Baerends EJ. Theor Chim Acta. 1977;43:261. [Google Scholar]; b) Noodleman L, Norman JG. J Chem Phys. 1979;70:4903. [Google Scholar]; c) Yamaguchi K, Jensen F, Dorigo A, Houk KN. Chem Phys Lett. 1988;149:537. [Google Scholar]; d) Noodleman L, Case DA. Adv Inorg Chem. 1992;38:423. [Google Scholar]; e) Lim MH, Worthington SE, Dulles FJ, Cramer CJ. In: Chemical Applications of Density Functional Theory. Laird BB, Ross RB, Ziegler T, editors. Vol. 629. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1996. p. 402. [Google Scholar]; f) Isobe H, Takano Y, Kitagawa Y, Kawakami T, Yamanaka S, Yamaguchi K, Houk KN. Mol Phys. 2002;100:717. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersson K, Malmqvist PA, Roos BO. J Chem Phys. 1992;96:1218. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orellana W, da Silva AJR, Fazzio A. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:155901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.155901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194101. doi: 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolg M, Wedig U, Stoll H, Preuss H. J Chem Phys. 1987;86:866. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hehre WJ, Radom L, Schleyer PvR, Pople JA. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory. Wiley; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Gagliardi L. Theor Chem Acc. 2006;116:307. [Google Scholar]; b) Gagliardi L, Heaven MC, Krogh JW, Roos BO. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:86. doi: 10.1021/ja044940l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gagliardi L, Roos BO. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:1599. doi: 10.1021/ic0261068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gagliardi L, Roos BO. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:893. doi: 10.1039/b601115m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hagberg D, Karlstrom G, Roos BO, Gagliardi L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14250. doi: 10.1021/ja0526719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Malmqvist PA, Pierloot K, Moughal Shahi AR, Cramer CJ, Gagliardi L. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:204109. doi: 10.1063/1.2920188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roos BO, Lindh R, Malmqvist PÅ, Veryazov V, Widmark PO. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:6575. doi: 10.1021/jp0581126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aquilante F, Malmqvist PÅ, Pedersen TB, Ghosh A, Roos BO. J Chem Theory Comp. 2008;4:694. doi: 10.1021/ct700263h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aquilante F, Pedersen TB, Sanchez de Meras A, Koch H, Lindh R, Roos BO. J Chem Phys. 2008;129:24113. doi: 10.1063/1.2953696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aquilante F, Pedersen TB, Lindh R. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:194106. doi: 10.1063/1.2736701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aquilante F, Lindh R, Pedersen TB. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:114107. doi: 10.1063/1.2777146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aquilante F, Pedersen TB, Sanchez de Meras A, Koch H. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:174101. doi: 10.1063/1.2360264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. MN-GFM (version 3.0) University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlström G, Lindh R, Malmqvist PA, Roos BO, Ryde U, Veryazov V, Widmark PO, Cossi M, Schimmelpfennig B, Neogrady P, Seijo L. Comp Mat Sci. 2003;28:222. [Google Scholar]