Abstract

Infection by an animal-like strain of rotavirus (PA260/97) was diagnosed in a child with gastroenteritis in Palermo, Italy, in 1997. Sequence analysis of VP7, VP4, VP6, and NSP4 genes showed resemblance to a G3P[3] canine strain identified in Italy in 1996. Dogs are a potential source of human viral pathogens.

Keywords: human rotavirus, canine rotavirus, G3P[3] genotype, VP7, VP4, VP6, NSP4, dispatch

Group A rotaviruses are enteric pathogens of humans and animals. Rotaviruses usually exhibit host species restriction, although interspecies transmission or reassortment between animals and humans viruses can occur (1). Sequence analysis of the genes that code for the 2 outer capsid proteins VP7 and VP4, for the inner capsid protein VP6, and for the nonstructural protein NSP4 is useful for gathering epidemiologic information and tracing the origin of unusual rotavirus strains. To date, 15 VP7 genotypes (G types 1–15), 27 VP4 genotypes (P types [1]–[27]), 4 VP6 subgroup specificities (SGs I, II, I+II, and nonI/nonII), and 5 NSP4 genotypes (A–E) have been established in human and animal group A rotaviruses (1,2). Human rotaviruses usually exhibit G1, G3, G4, and G9 types in association with P[8] type, SGII specificity, and NSP4 B type; G2 rotaviruses are more often associated with P[4] type, SGI specificity, and NSP4 A type (1). By polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), most animal SGI and SGII and human SGII rotavirus strains display a “long” pattern of migration (e-type) of the 11 dsRNA genomic segments; almost all SGI human rotavirus strains possess a “short” e-type (1).

A number of strains with unusual VP7 and VP4 genes, regarded as animal-like, have been sporadically identified in humans and have acquired epidemiologic relevance in some geographic areas (3). Dogs are regarded as vectors of viral, bacterial, or parasitic zoonoses for persons of all ages, but risks for transmission of enteric viruses are almost ignored. However, early in the study of rotavirus epidemiology, symptomatic and asymptomatic infections by canine/feline-like rotavirus strains (HCR3A, HCR3B, Ro1845), characterized as G3P5A[3], long e-type and SGI, were identified in young children (4,5).

The Study

In February 1997, rotavirus infection was diagnosed (by PAGE analysis) in a 2-year-old child hospitalized with severe acute diarrhea at the “G. Di Cristina” Children’s Hospital of Palermo. The virus, PA260/97, exhibited a long e-type and was recognized by an SG-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) and by a VP7-specific MAb as SGI and G3 (6). Accordingly, strain PA260/97 displayed a genetic/antigenic constellation that is usually observed in animal-like viruses. For confirmation of the initial antigenic characterization and information about the VP4 (P) genotype, strain PA260/97 was characterized at the molecular level. By PCR genotyping of the VP7 and VP4 genes with panels of primers specific for various human G and P types (3,7,8), the VP7 was characterized as G3 and the VP4 was untypeable. To characterize strain PA260/97 in more detail, we determined the sequence of the VP7, VP4 (VP8*), VP6, and NSP4 genes. We also determined the VP7, NSP4, and VP6 sequences of human strain PAH101/97 (G3P[8], SGII, long e-type), detected in Palermo in the same year, as well as the sequences of the VP8*, VP6, and NSP4 genes of 2 G3P[3], SGI, long e-type strains,RV198/95, and RV52/96, isolated from dogs in Italy in 1995 and 1996, respectively (9).

The sequences of human strains PA260/97 and PAH101/97 and of canine strains RV198/95 and RV52/96 have been deposited in GenBank. The accession numbers are as follows: EF442738 (VP6), EF442733 (VP7), EF442735 (VP8*), and EF442741 (NSP4) for strain PA260/97; EF534715 (VP6), EF442734 (VP7), and EF534716 (NSP4) for strain PAH101/97; EF442737 (VP6), EF442736 (VP8*), and EF442739 (NSP4) for strain RV198/95; EF442742 (VP6), EF442740 (VP8*), and EF442743 (NSP4) for strain RV52/96.

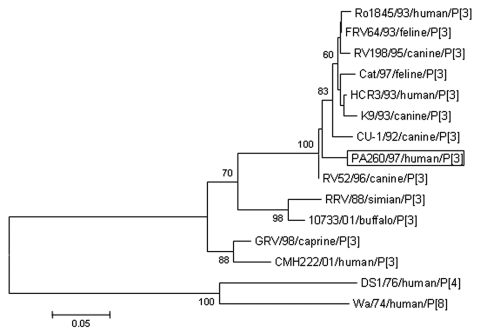

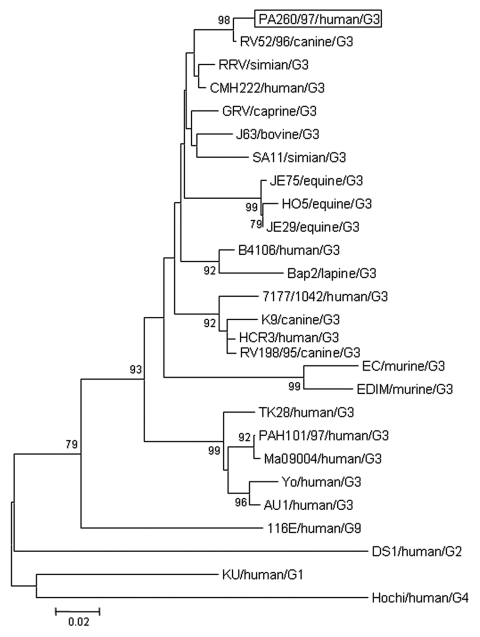

The VP8* of strain PA260/97 displayed the highest amino acid (aa) identity (98%) to the canine strain RV52/96, G3P[3], isolated in Italy in 1996 (Figure 1). Similar, the VP7 of strain PA260/97 displayed the highest identity to G3 rotaviruses, with the best match (99% nt and aa) to the canine strain RV52/96; identity to reference human G3 strains (YO, AU-1, Ma09004, TK28) and to the human G3 strain PAH101/97, isolated in Palermo in 1997, ranged from 77% to 78% nt and from 88% to 90% aa. In the phylogenetic VP7-based analysis (Figure 2), human strain PA260/97 clustered with animal G3 strains. Species-specific patterns have been demonstrated in the VP7 gene of G3 human and animal rotaviruses (9). These patterns are suggestive of mechanisms of host-species restriction and are useful for tracing the origin of unusual rotavirus strains.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence derived from VP4 gene of the PA260/97 human rotavirus strain and other P[3] rotavirus strains. The tree was generated by the neighbor-joining method using the ClustalW program (http://dambe.bio.uottawa.ca/dambe.asp). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions (×100).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of deduced amino acid sequence derived from VP7 gene of the PA260/97 human rotavirus strain and other G3 rotavirus genotypes. The tree was generated by the neighbor-joining method using the ClustalW program (http://dambe.bio.uottawa.ca/dambe.asp). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions (×100).

A close genetic relationship between human strain PA260/97 and canine strain RV52/96 was also observed by comparing the genes that encode VP6 and NSP4. On the basis of MAb reactivity, strain PA260/97 was characterized as SGI and strain PAH101/97 was characterized as SGII. Sequencing of an informative fragment of the VP6 gene (10) showed a close genetic relationship (97% aa) between strain PA260/97 and canine strain RV52/96 and only 86% aa identity with strain PAH101/97. Sequence analyses of NSP4 enabled characterization of strains PA260/97, RV198/95, and RV52/96 into the NSP4 genotype C; strain PAH101/97 (G3P[8]) was characterized as NSP4 B genotype. The highest identity was observed between strains PA260/97 and RV52/96 (98% nt and 99% aa).

Conclusions

Rotavirus strains with a G3P[3] combination are usually detected in cats and dogs. Despite only a few reports of rotavirus isolation from dogs with gastroenteritis, all canine strains identified thus far in the United States, Japan, and Europe (CU-1, A79-10, LSU79C-36, RS15, RV198/95, and RV52/96) display G3 and P[3] specificities (9). More recently, G3P[3] rotaviruses have also been identified in monkeys and goats (1,11). In contrast, detection of G3P[3] in humans is uncommon; only 4 G3P[3] strains—HCR3A, HCR3B (4,12), Ro1845 (5), and CMH222 (13)—have been reported. By sequence analysis and by RNA-RNA hybridization, strains HCR3A and Ro1845 were found to be related to canine and feline rotaviruses rather than to human G3 rotaviruses; strain CMH222 appeared to be genetically related to both simian and caprine G3P[3] rotaviruses (13). Genetic reassortment between human and canine rotaviruses may also have occurred. The Mexican rotavirus strain 7177-1042 bears a common human VP4 gene, P[8], in conjunction with a canine-like VP7 gene, closely related to the VP7 of canine strain RV198/95 (14).

Canine rotavirus infection is considered a minor disease in young dogs (pups) because it is usually mild or unapparent; however, serologic investigations have shown a high prevalence of antibodies to rotavirus in adult dogs (15). Previous documented examples of infections in humans by canine-like rotavirus strains have been associated with either asymptomatic (strains HCR3A and HCR3B) or symptomatic (strain Ro1845) clinical forms of disease (4,5,12). Strain PA260/97 in the 2-year-old child was associated with enteritis severe enough to require hospitalization. Therefore, the results of this study reinforce the hypothesis that canine-like rotaviruses may be able to not only cross the species barriers but also to induce severe disease forms in children. The lack of systematic surveillance of rotavirus infection in small animals (e.g., dogs and cats) and the fact that most rotavirus infections in such animals may go undetected hinder the ability to establish firm epidemiologic connections. In conclusion, complementing the human rotavirus surveillance programs with surveillance in animals is paramount to understanding the global ecology of rotaviruses and to identifying and characterizing interspecies transmission events and virus evolution.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research) (Fondi di Ateneo ex 60%).

Biography

Dr De Grazia is a microbiology specialist and research assistant at the University of Palermo, Dipartimento di Igiene e Microbiologia “G. D'Alessandro.” Her primary research interests are microbial typing, viral enteric pathogens, and viral epidemiology.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: De Grazia S, Martella V, Giammanco GM, Gòmara MI, Ramirez S, Cascio A, et al. Canine-origin G3P[3] rotavirus strain in child with acute gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2007 Jul [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/eid/content/13/7/1091.htm

References

- 1.Kapikian AZ, Hoshino Y, Chanock RM. Rotaviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Martin MA, Lamb RA, Roizman B, et al., editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. p. 1787–833. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khamrin P, Maneekarn N, Peerakome S, Chan-it W, Yagyu F, Okitsu S, et al. Novel porcine rotavirus of genotype P[27] shares new phylogenetic lineage with G2 porcine rotavirus strain. Virology. 2007;361:243–52. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iturriza-Gomara M, Kang G, Gray J. Rotavirus genotyping: keeping up with an evolving population of human rotaviruses. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:259–65. 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos N, Clark HF, Hoshino Y, Gouvea V. Relationship among serotype G3P5A rotavirus strains isolated from different host species. Mol Cell Probes. 1998;12:379–86. 10.1006/mcpr.1998.0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboudy Y, Shif I, Zilberstein I, Gotlieb-Stematsky T. Use of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies and analysis of viral RNA in the detection of unusual group A human rotaviruses. J Med Virol. 1988;25:351–9. 10.1002/jmv.1890250312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascio A, Vizzi E, Alaimo C, Arista S. Rotavirus gastroenteritis in Italian children: can severity of symptoms be related to the infecting virus? Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1126–32. 10.1086/319744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentsch JR, Glass RI, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, et al. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouvea V, Glass RI, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark HF, Forrester B, et al. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martella V, Pratelli A, Elia G, Decaro N, Tempesta M, Buonavoglia C. Isolation and genetic characterization of two G3P5A[3] canine rotavirus strains in Italy. J Virol Methods. 2001;96:43–9. 10.1016/S0166-0934(01)00312-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iturriza Gomara M, Wong C, Blome S, Desselberger U, Gray J. Molecular characterization of VP6 genes of human rotavirus isolates: correlation of genogroups with subgroups and evidence of independent segregation. J Virol. 2002;76:6596–601. 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6596-6601.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JB, Youn SJ, Nakagomi T, Park SY, Kim TJ, Song CS, et al. Isolation, serologic and molecular characterization of the first G3 caprine rotavirus. Arch Virol. 2003;148:643–57. 10.1007/s00705-002-0963-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Clark HF, Gouvea V. Nucleotide sequence of the VP4-encoding gene of an unusual human rotavirus (HCR3). Virology. 1993;196:825–30. 10.1006/viro.1993.1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khamrin P, Maneekarn N, Peerakome S, Yagyu F, Okitsu S, Ushijima H. Molecular characterization of a rare G3P[3] human rotavirus reassortant strain reveals evidence for multiple human-animal interspecies transmissions. J Med Virol. 2006;78:986–94. 10.1002/jmv.20651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laird AR, Ibarra V, Ruiz-Palacios G, Guerrero ML, Glass RI, Gentsch JR. Unexpected detection of animal VP7 genes among common rotavirus strains isolated from children in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4400–3. 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4400-4403.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mochizuki M, Minami K, Sakamoto H. Seroepizootiologic studies on rotavirus infections of dogs and cats. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1986;48:957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]