Abstract

The role of the general internist in the care of breast cancer survivors is increasing as the number of women living with breast cancer continues to rise. Most breast cancers occurring in women older than 50 years are estrogen receptor– and/or progesterone receptor–positive, and adjuvant endocrine therapy plays an important role in the treatment plan. Aromatase inhibitors are becoming the preferred endocrine therapy, and general internists caring for breast cancer survivors need to be familiar with their use and adverse effect profile. This article reviews the use of aromatase inhibitors, the frequency of common adverse effects, and strategies for their management.

AI = aromatase inhibitor; ATAC = Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination; BIG = Breast International Group; CYP = cytochrome P450; ER = estrogen receptor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

As of 2009, more than 2.5 million women in the United States were living with breast cancer.1 With continued improvement in survival rates, this group of survivors will grow and, with it, a need for a better understanding of the medical issues associated with breast cancer survivorship and the adverse effects of prescribed medications.

Most breast cancers occurring in women older than 50 years are estrogen receptor (ER)– and/ or progesterone receptor–positive and are treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy.2 The goal of adjuvant endocrine therapy is to prevent breast cancer cells from receiving stimulation from endogenous estrogen and thus prevent ER- and progesterone receptor–positive cancer cells from growing and spreading. In addition, the mechanism of action includes the inhibition of peritumoral aromatase and marked reduction in the local concentrations of estrogen in the breast. Increasingly, the preferred adjuvant endocrine therapy for this group is third-generation aromatase inhibitors (AIs).3

The Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group demonstrated the efficacy of tamoxifen, a selective ER modulator, in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients.4 Before publication of the initial results of the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial in 2002, tamoxifen was the most prescribed adjuvant endocrine therapy.5 Since 2001, the efficacy of third-generation AIs has been well established, and large clinical trials have shown AIs to be superior to tamoxifen in rates of disease-free survival and incidence of contralateral breast cancers. Additionally, time to recurrence was prolonged and the number of distant metastases was reduced with AI vs tamoxifen therapy.6,7 Physicians caring for patients with breast cancer need to be familiar with the indications, efficacy, and adverse effect profile of selective ER modulators and AIs.

This article aims to provide nononcologists with a relevant review of the use of AIs in postmenopausal women with ER-positive breast cancer and to discuss strategies for evaluating and managing adverse effects associated with their use.

BIOCHEMISTRY

Aromatase, a member of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme family, is a product of the CYP19 gene and is the rate-limiting step in the conversion of androstenedione to estrone and of testosterone to estradiol.8 The CYP19 gene is highly expressed in the human placenta and in the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicles. Nonglandular tissues having lower levels of aromatase activity include subcutaneous, fat, liver, muscle, brain, normal breast, and breast cancer tissues.9 The activity of the enzyme is increased by alcohol, advanced age, obesity, insulin, and gonadotropins.9

CLINICAL EFFICACY AND MECHANISM OF ACTION

Aromatase inhibitors are indicated for adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal but not premenopausal women.10,11 Approximately 95% of estrogen production in premenopausal women occurs in the ovary, whereas conversion of adrenal androgens to estrogen is the predominant source of estrogen production in postmenopausal women.12 Aromatase inhibitors are not used in premenopausal women because the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis is activated in response to the decrease in systemic levels of estrogen after AI administration. This activation results in an increase in gonadotropin secretion and in ovarian production of estrogen, androgen, and aromatase.13 The androgens androstenedione and testosterone are then converted to the estrogens estrone and estradiol, respectively. through the action of aromatase, a CYP enzyme.14 Guidelines for the use of AIs in women who become postmenopausal as a result of chemotherapy or ovarian ablation have not been established. An abstract by Goss et al15 suggested that women who were premenopausal at the initiation of tamoxifen therapy but appeared postmenopausal after 5 years of therapy had improvement in disease-free survival as a result of aromatase inhibition. Studies are currently under way to better understand the role of AIs or tamoxifen after ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women (eg, Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial10 and Tamoxifen and Exemestane trial13). Aromatase inhibitors are contraindicated in pregnancy.

Third-generation AIs are specific for the aromatase enzyme. Aromatase inhibitors block the conversion of androgens to estrogens via the aromatase enzyme, resulting in up to a 95% decrease in endogenous estrogen levels. This mechanism of action differs from that of tamoxifen, which effectively blocks estrogen's effect via competitive inhibition of estrogen binding to ERs and an antagonist (and agonist) for ER and down-regulates expression of genes controlled by ER expression.

Aromatase inhibitors are classified as steroidal (type I) or nonsteroidal (type II) inhibitors. Exemestane, a steroidal inhibitor that is a structural derivative of androstenedione (the substrate of aromatase), irreversibly inhibits the aromatase enzyme. In contrast, the nonsteroidal compounds letrozole and anastrozole reversibly bind to the aromatase enzyme.16

ADVERSE EFFECTS

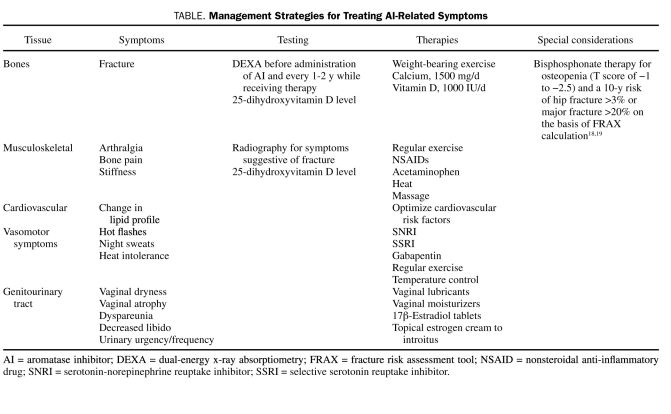

Most adverse effect trials have compared individual agents to tamoxifen. A number of large randomized controlled trials have clearly shown that AIs have a different adverse effect profile than tamoxifen and, in general, are better tolerated.3 Aromatase inhibitors are associated with significantly fewer venous thromboembolic events and do not cause the endometrial proliferation that can be seen with tamoxifen.17 As a class, AIs have a number of adverse effects (Table), a detailed discussion of some of which follows.

TABLE.

Management Strategies for Treating AI-Related Symptoms

HOT FLASHES

It is well known that many postmenopausal women experience hot flashes as a result of estrogen deprivation. Hot flashes are also recognized as a common and major adverse effect of adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Thus, susceptible women receiving antiestrogen therapy may experience an exacerbation of vasomotor symptoms, especially during the early postmenopausal years. Occurrence rates for hot flashes in studies of tamoxifen vary from 57% to 85%.20 Aromatase inhibitors also cause hot flashes but may cause fewer than tamoxifen. The ATAC trial demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the incidence of hot flashes in patients treated with anastrozole vs those receiving tamoxifen (35.7% vs 39.7%; odds ratio, .80; P<.0001), and the BIG (Breast International Group) 1-98 trial demonstrated similar reductions, with 32.8% of patients reporting hot flashes while taking letrozole and 37.3% reporting them while taking tamoxifen.21 In contrast, a more recent study demonstrated no difference in hot flash occurrence in patients taking tamoxifen vs those taking exemestane.22

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HOT FLASHES IN PATIENTS RECEIVING AI THERAPY

The treatment for hot flashes in patients receiving AI therapy includes nonhormonal measures, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and gabapentin. Although most hot flash studies conducted to date have included tamoxifen, a summary of the data demonstrates that a similar approach to hot flash treatment should be adopted in women receiving tamoxifen and those who are not.23 In fact, aromatase inhibition does not affect the use of SSRIs for hot flash therapy, whereas tamoxifen use may be affected. Because tamoxifen is metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme and some SSRIs are known to inhibit this enzyme, conversion of tamoxifen to its active metabolite endoxifen may be reduced, causing a decrease in tamoxifen efficacy.24

EFFECT ON BONE HEALTH

Aromatase inhibitors cause statistically significant increases in bone loss and fracture rates when compared with tamoxifen or placebo.21,25 Presumably, estrogen inhibition affects the bone remodeling cycle, favoring increased osteoclastic activity and net loss of bone mineral. Markers of bone resorption have been shown to increase steadily during 24 months of therapy26; that increase correlated with an increase in fractures seen with each of the currently used third-generation AIs. An interrelation between aromatase activity, CYP19 expression, and vitamin D has been postulated.27 The different classes of AIs may have differential effects on bone on the basis of the chemical structures of the molecules and the androgenic activity of the compounds at the level of the bone osteoblasts. Exemestane, a steroidal inhibitor, may exert a slightly less negative effect on fracture risk because it may have more androgenic activity than the nonsteroidal compounds.16

Because patients with breast cancer have an increased risk of osteoporosis and, more importantly, an increased risk of fracture even before treatment with AIs, careful attention to bone health is recommended before consideration of AI therapy.28 The WHI-OS (Women's Health Initiative Observational Study) cohort demonstrated a 31% increased risk of fracture in women with vs those without breast cancer. Women with breast cancer but no bony metastases had a 5-fold increased risk of vertebral compression fractures.29 The mechanism underlying the increased risk of fracture in women with breast cancer is not fully understood but may be related to the induction of premature menopause by cancer chemotherapy.

Recommendations for treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis in patients with breast cancer differ among experts. The American Society of Clinical Oncologists recommends bisphosphonate therapy for all women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer who have a T score of less than −2.5. The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends institution of bisphosphonate therapy for patients who meet criteria for a diagnosis of osteopenia (T score of −1.0 to −2.5) and a 10-year risk of hip fracture greater than 3% or of major fracture greater than 20% based on the World Health Organization fracture risk assessment tool calculation.18,19,28 Physicians caring for patients treated with AIs should assess baseline bone mass and follow up carefully because of the increased risk of bone loss. Fracture risk is increased by approximately 7.7% to 11%17 but has been shown to be reduced with bisphosphonate therapy such that recognition of risk and appropriate intervention are mandatory. Regular follow-up assessment of bone density and awareness of and adherence to nonpharmacologic therapies, such as lifestyle changes, adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, physical activity, and fall prevention, should also be encouraged.30 Vitamin D levels should be measured routinely and optimized throughout the patient's lifetime.31 Measurement of bone density should be considered in all women before initiation of therapy with an AI and every 1 to 2 years thereafter. In women with a diagnosis of osteopenia and increased risk of fracture as assessed by the fracture risk assessment tool calculation, consideration should be given to treatment with a bisphosphonate. If a patient has an established diagnosis of osteoporosis at baseline, adherence to national recommendations for treatment is recommended.30

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK

All studies comparing the risks of tamoxifen vs AIs have shown an overall decreased risk of venous thromboembolic events in those taking AIs vs those taking tamoxifen.4 The BIG 1-98 trial demonstrated an excess of severe events (chronic heart failure and ischemic heart disease) in patients treated with letrozole vs tamoxifen. Additionally, anastrozole in the ATAC trial and letrozole in the BIG 1-98 trial were associated with a significant increase in hypercholesterolemia.17,21 Interestingly, no such increase was seen with exemestane.22 These findings suggest that nonsteroidal AIs may have a slightly more unfavorable effect on cardiovascular risk. The subtle differences between these compounds may have implications in the choice of therapies for patients with multiple comorbid conditions and offer the opportunity for further study and refinement. However, other than careful medical assessment, no specific precautions, lipid assessment, or cardiovascular risk assessment is currently required for patients receiving therapy with AIs. In contrast, there is evidence of lipid lowering and some cardioprotection with tamoxifen. No significant difference in cardiovascular risk was seen in a study comparing a 5-year course of monotherapy with letrozole vs tamoxifen.32

MUSCULOSKELETAL CONCERNS

Data from large published trials suggest that musculoskeletal symptoms, including joint pain and stiffness, occur in 44% to 47% of patients taking AIs.17,21,22,33 Although not life-threatening, these adverse effects account for discontinuation of therapy in up to 20% of patients. Risk factors for the occurrence of musculoskeletal concerns are unclear; however, small studies suggest that there may be a link to low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D.34 The etiology of these symptoms is unknown, and often the most serious symptoms occur in the first 6 months of therapy, with some improvement with continued use. Alternatively, a switch to another AI may provide relief. Definitive therapy for AI-induced arthralgias has not been developed. A recent study of women with AI-induced arthralgias treated with true acupuncture for a 6-week period demonstrated significant improvement in joint pain and stiffness and was well tolerated.35 Some relief is often provided by a combination of therapies, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gentle exercise, and optimization of vitamin D levels.36

GENITOURINARY ATROPHY

Genitourinary atrophy is a natural consequence of postmenopausal estrogen loss. The marked decrease in systemic levels of estrogen in postmenopausal women leads to substantial changes in the vaginal epithelium. Sexual and urinary function can be affected, and women may present with symptoms of decreased libido; vaginal dryness; dyspareunia; urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence; and frequent infections.37 However, no significant difference has been reported between AIs and tamoxifen or placebo with regard to multiple symptoms influencing quality of life.10

The marked decrease in systemic estrogen levels associated with administration of AIs can further exacerbate genitourinary symptoms.38 Vaginal lubricants can improve comfort with intercourse, and regular coital activity can improve blood flow to vulvovaginal tissues and improve lubrication.39 The use of systemic estrogen therapy is not recommended for breast cancer survivors, and the safety of local estrogen therapy in the treatment of genitourinary atrophy has not been established. However, the use of local estrogen therapy to treat moderate to severe symptoms of genitourinary atrophy is becoming more accepted in clinical practice.39 A small study of 7 postmenopausal women examined the effect of local estrogen therapy on serum estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone, and lutenizing hormone levels during a 12-week period. This study showed that estradiol levels increased in the short term after administration of vaginal estradiol tablets but decreased to postmenopausal levels in 6 of the 7 women at 12 weeks. This may suggest that the initial absorption of estradiol is increased when the tissue is most atrophic. The authors concluded that the use of local estrogen therapy is contraindicated in patients with breast cancer treated with AIs.40 In a small cohort study of women previously treated for breast cancer, the risk of recurrence did not increase with vaginal estrogen therapy.41 Some experts recommend the administration of local estrogen in small but consistent dosages to address these symptoms because the effect on quality of life is considerable.38 The application of small amounts of local estrogen on a regular basis may be more desirable than intermittent use because the return of atrophic change encourages more systemic absorption of estrogen via damaged epithelium and can yield an undesirable increase in systemic levels.42 Frequent urinary tract infections may respond to estrogenization of vaginal tissues and may influence the decision to treat with local estrogen therapy.43 Decisions to institute therapy with local estrogen must be made collaboratively with patients, calculating the risks and benefits for each individual. No studies document the long-term effect on cancer risk of this approach to the management of urogenital atrophy.

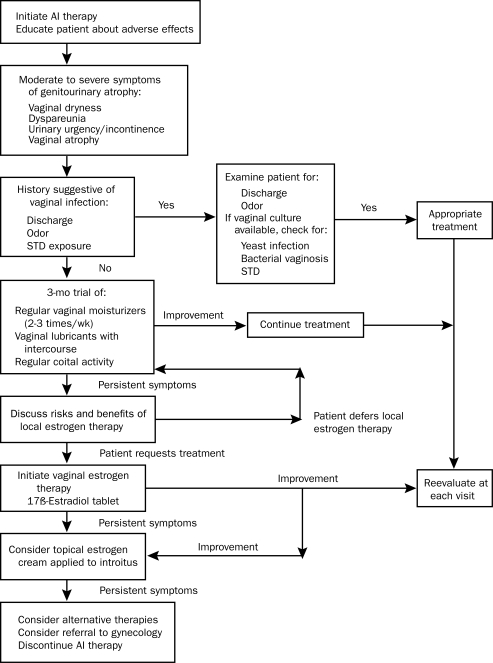

Intravaginal application of dehydroepiandrosterone holds promise as a novel approach to the treatment of genitourinary atrophy in breast cancer survivors. It acts as a hormone precursor and, when applied intravaginally, allows for local conversion to active androgen. A recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of ovules containing different concentrations of dehydroepiandrosterone demonstrated efficacy at all doses.44 This new treatment strategy may benefit women who need treatment but wish to avoid estrogen therapy (Figure).

FIGURE.

Management of genitourinary atrophy in patients receiving aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy. STD = sexually transmitted disease.

COGNITIVE FUNCTION

Cognitive dysfunction after breast cancer treatment is reported in up to one-third of patients, and most studies link it to chemotherapy.45 Estrogen receptors are identified in many parts of the brain and may play an important role in cognition.46 The long-term effect of estrogen suppression on cognitive function is unknown, and results from studies are conflicting. Tools to effectively measure cognitive function and data from large-scale trials are lacking. In a small cross-sectional study, 31 women with early-stage breast cancer were treated with tamoxifen or anastrozole for a minimum of 3 months. Results of this study showed that women treated with anastrozole had poorer verbal and visual learning as well as poorer memory than women treated with tamoxifen.47 In contrast, the International Breast Intervention Study demonstrated no difference in cognition among women randomly assigned to receive anastrozole vs placebo.48

NONSPECIFIC ADVERSE EFFECTS

Aromatase inhibitors may also cause a number of nonspecific adverse effects, including nausea, diarrhea, rash, hair thinning, and headache. Physicians treating patients with these medications need to be aware of the potential for nonspecific adverse effects.49

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Genomic analysis may hold promise for identifying women at risk for the development of serious musculoskeletal symptoms with the use of AIs. The role of serum estradiol measurements in assessing efficacy and dosing of AIs is still unclear and not indicated. Large ongoing randomized studies are comparing a 5-year course vs a 10-year course of AIs.

CONCLUSION

Aromatase inhibitors are currently indicated as first-line adjuvant endocrine therapy in the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in postmenopausal women with ER-positive tumors. The efficacy of these medications in prolonging disease-free survival and decreasing the risk of contralateral breast cancer has led to a considerable increase in the frequency of their use. Many of the adverse effects associated with these medications may be more readily recognized by physicians familiar with the adverse effect profiles of these drugs. Reducing the severity and frequency of adverse effects may improve quality of life for patients taking AIs and prevent discontinuation of this well-documented and beneficial therapy. Undesirable long-term effects such as fractures can be prevented with appropriate recognition and treatment.

Supplementary Material

On completion of this article, you should be able to (1) examine the use of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer survivors, (2) identify common adverse effects associated with aromatase inhibitors, and (3) recommend strategies for management of common adverse effects.

CME Questions About Managing AIs in Breast Cancer Survivors

-

Before initiating AI therapy, which one of the following is an important step to consider?

Perform bone mineral densitometry scan and calculate risk using the World Health Organization fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX)

Measure levels of bone turnover markers

Measure level of serum calcium

Perform bone scan

Initiate bisphosphonate therapy

-

Which one of the following statements regarding bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal patients undergoing AI treatment is accurate?

Oral bisphosphonate therapy is more effective than intravenous bisphosphonate therapy

Bisphosphonate therapy is ineffective when used concurrently with AIs

Supplemental calcium and vitamin D are recommended in all patients taking both AIs and bisphosphonates

Once-weekly administration of oral bisphosphonate therapy is superior to daily therapy

Intranasal calcitonin is an alternative to bisphosphonate therapy in the treatment of AI-induced bone loss

-

Which one of the following adverse effects is most commonly reported by women taking AIs?

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

Hot flashes and arthralgias

Hair thinning

Depression

Breast pain

-

Which one of the following is a commonly prescribed steroidal, third-generation inhibitor?

Raloxifene

Letrozole

Exemestane

Tamoxifen

Anastrozole

-

Which one of the following approaches would be reasonable in the management of vaginal atrophy?

Initial therapy with vaginal lubricants and consideration of intravaginal estrogen

Tamoxifen

Corticosteroids

Systemic estrogen

Vinegar douches

This activity was designated for 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s).™

Because the Concise Review for Clinicians contributions are now a CME activity, the answers to the questions will no longer be published in the print journal. For CME credit and the answers, see the link on our Web site at mayoclinicproceedings.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Detailed Guide: Breast Cancer: What are the Key Statitics for Breast Cancer? American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_breast_cancer_5.asp?sitearea= http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_breast_cancer_5.asp?sitearea= Accessed April 27, 2010.

- 2.Li CI, Daling JR, Malone KE. Incidence of invasive breast cancer by hormone receptor status from 1992 to 1998. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):28-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altundag K, Ibrahim NK. Aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer: an overview. Oncologist 2006;11(6):553-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;365(9472):1687-1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359(9324):2131-2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingle JN, Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Davies C. Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer: meta-analyses of randomized trials of monotherapy and switching strategies [abstract 12]. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2, suppl):66s [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forbes JF, Cuzick J, Buzdar A, Howell A, Tobias JS, Baum M. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):45-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh D, Griswold J, Erman M, Pangborn W. Structural basis for androgen specificity and oestrogen synthesis in human aromatase. Nature 2009;457(7226):219-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith IE, Dowsett M. Aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2431-2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):619-629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma S, Sehdev S, Joy A, Madarnas Y, Younus J, Roy JA. An updated review on the efficacy of adjuvant endocrine therapies in hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2009;16(suppl 2):S1-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rugo HS. The breast cancer continuum in hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women: evolving management options focusing on aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(1):16-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortmann O, Cufer T, Dixon JM, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for perimenopausal women with early breast cancer. Breast 2009;18(1):2-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson ER, Mahendroo MS, Means GD, et al. Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(3):342-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goss P, Ingle J, Martino S, et al. Outcomes of women who were premenopausal at diagnosis of early stage breast cancer in the NCIC CTG MA17 Trial [abstract 13]. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24, suppl):487s [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponzone R, Mininanni P, Cassina E, Pastorino F, Sismondi P. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: different structures, same effects? Endocr Relat Cancer 2008;15(1):27-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 2005;365(9453):60-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillner BE, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4042-4057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Osteoporosis Foundation NOF's Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. http://www.nof.org/professionals/Clinicians_Guide.htm. http://www.nof.org/professionals/Clinicians_Guide.htm Accessed March 27, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mom CH, Buijs C, Willemse PH, Mourits MJ, de Vries EG. Hot flushes in breast cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;57(1):63-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thurlimann B, et al. Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):486-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coombes RC, Kilburn LS, Snowdon CF, et al. Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2-3 years' tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;369(9561):559-570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Sloan JA, et al. Mayo Clinic and North Central Cancer Treatment Group hot flash studies: a 20-year experience. Menopause 2008;15(4, pt 1):655-660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetz MP, Knox SK, Suman VJ, et al. The impact of cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism in women receiving adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;101(1):113-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. Randomized trial of letrozole following tamoxifen as extended adjuvant therapy in receptor-positive breast cancer: updated findings from NCIC CTG MA.17. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(17):1262-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonning PE, Geisler J, Krag LE, et al. Effects of exemestane administered for 2 years versus placebo on bone mineral density, bone biomarkers, and plasma lipids in patients with surgically resected early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5126-5137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geisler J, Lønning PE. Impact of aromatase inhibitors on bone health in breast cancer patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010February28;118(4-5):294-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Powles T, Paterson AH, Ashley S, Spector T. A high incidence of vertebral fracture in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1999;79(7-8):1179-1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z, Maricic M, Pettinger M, et al. Osteoporosis and rate of bone loss among postmenopausal survivors of breast cancer. Cancer 2005;104(7):1520-1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadji P, Body JJ, Aapro MS, et al. Practical guidance for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(8):1407-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hines SL, Jorn K, Thompson KM, Larson JM. Breast cancer survivors and vitamin D: a review. Nutrition 2010;26(3):255-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, et al. BIG 1-98 Collaborative Group Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):766-776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3877-3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waltman NL, Ott CD, Twiss JJ, Gross GJ, Lindsey AM. Vitamin D insufficiency and musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(3):143-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, et al. Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1154-1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henry NL, Giles JT, Stearns V. Aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms: etiology and strategies for management. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22(12):1401-1408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein I, Alexander JL. Practical aspects in the management of vaginal atrophy and sexual dysfunction in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2005;(2, suppl):3154-3165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lester JL, Bernhard LA. Urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009;36(6):693-698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganz PA. Breast cancer, menopause, and long-term survivorship: critical issues for the 21st century. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):136-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendall A, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, Smith I. Caution: vaginal estradiol appears to be contraindicated in postmenopausal women on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(4):584-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dew JE, Wren BG, Eden JA. A cohort study of topical vaginal estrogen therapy in women previously treated for breast cancer. Climacteric 2003;6(1):45-52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trinkaus M, Chin S, Wolfman W, Simmons C, Clemons M. Should urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors be treated with topical estrogens? Oncologist 2008;13(3):222-231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):689-690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Effect of intravaginal dehydroepi-androsterone (prasterone) on libido and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2009;16(5):923-931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quesnel C, Savard J, Ivers H. Cognitive impairments associated with breast cancer treatments: results from a longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;116(1):113-123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibbs RB. Estrogen therapy and cognition: a review of the cholinergic hypothesis. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):224-253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bender CM, Sereika SM, Brufsky AM, et al. Memory impairments with adjuvant anastrozole versus tamoxifen in women with early-stage breast cancer. Menopause 2007;14(6):995-998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenkins VA, Ambroisine LM, Atkins L, Cuzick J, Howell A, Fallowfield LJ. Effects of anastrozole on cognitive performance in postmenopausal women: a randomised, double-blind chemoprevention trial (IBIS II). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(10):953-961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibson L, Lawrence D, Dawson C, Bliss J. Aromatase inhibitors for treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD003370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.