Abstract

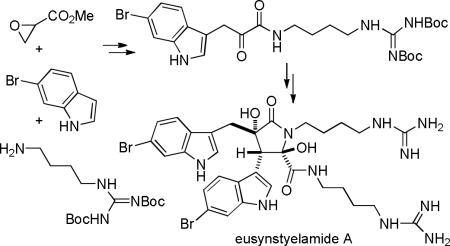

The synthesis of (±)-eusynstyelamide A has been accomplished in six steps in 13% overall yield from 6-bromoindole, methyl glycidate, and Boc-protected agmatine. If oxygen is carefully excluded from the reaction, the key NaOH-catalyzed aldol dimerization of the α-ketoamide proceeded efficiently to give Boc-protected eusynstyelamide A.

Tapiolas and co-workers recently reported the isolation of eusynstyelamides A (1), B (2), and C (3) from the Great Barrier Reef ascidian Eusynstyela latericius and assigned their structures from analysis of the spectral data (see Figure 1).1 The spectral data for 1 are virtually identical to those reported for eusynstyelamide (4), isolated from E. misakiensis,2 indicating that the structure of 4 should be reassigned as 1, rather than the acyclic ketone dihydrate. Eusynstyelamides A–C (1–3) inhibit neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), with IC50 values of 41.7, 4.3, and 5.8 μM, respectively, and show slight antibiotic activity against Staphylococcus aureus.

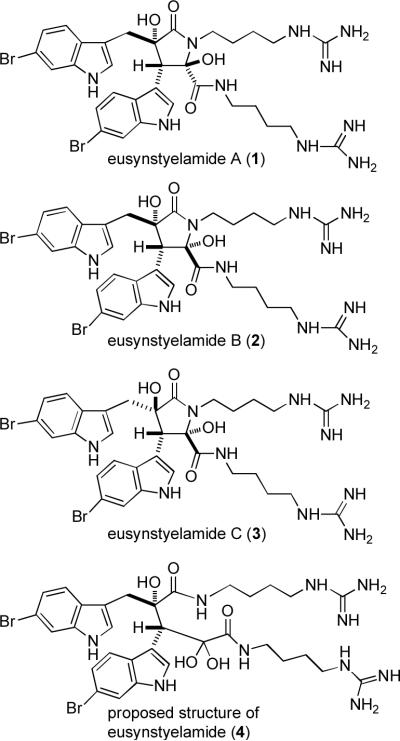

Figure 1.

Structures of eusynstyelamides A (1), B (2), and C (3) and the proposed structure of eusynstyelamide (4).

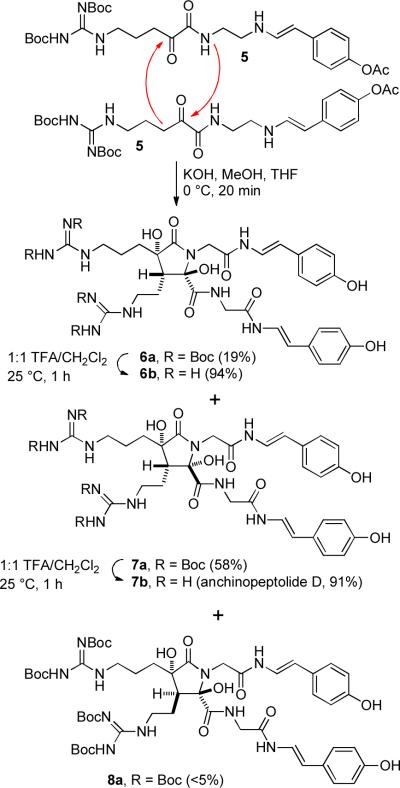

We were intrigued by these structures because the dihydroxybutyrolactam core is identical to that of anchinopeptolide D (7b), which we synthesized several years ago (see Scheme 1).3 α-Ketoamide 5 underwent an aldol dimerization on treatment with KOH in THF/MeOH. The amide nitrogen of the initially formed aldol adduct cyclized to the remaining ketone to form a dihydroxybutyrolactam. The phenol acetate was also hydrolyzed under these reaction conditions. We isolated three of the four possible diastereomeric products. The major product was anchinopeptolide D precursor 7a, which was formed in 58% yield. Lactam 6a, which was isolated in 19% yield, has the opposite stereochemistry at the hemiaminal center, but was formed from the same aldol adduct 10 (see Scheme 2) as 7a. The third product 8a, which was isolated in <5% yield, was formed from the diastereomeric aldol product. Cleavage of the four Boc groups of 6a and 7a in 1:1 TFA/CH2Cl2 for 1 h at 25 °C afforded 6b (94%) and anchinopeptolide D (7b, 91%), respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Anchinopeptolide D (7b)

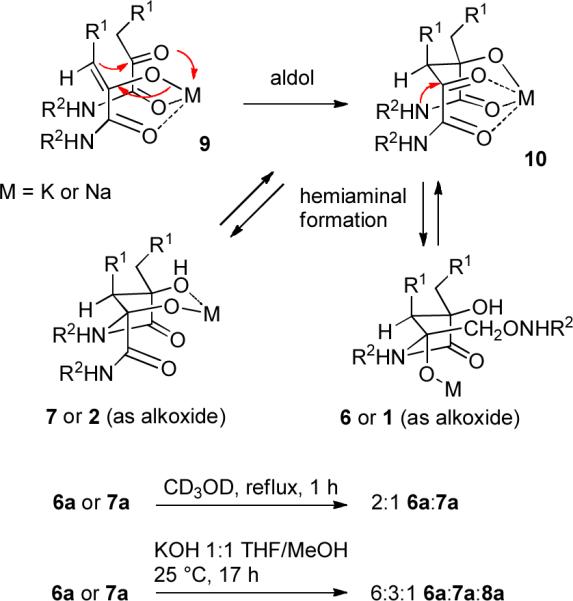

Scheme 2.

Mechanistic Considerations and Equilibration Studies

The stereochemistry of the major aldol adduct 10 can be rationalized by consideration of a chelated transition state for the aldol reaction. Enolization should give the Z-enolate to avoid steric interactions between the amide and the R1 substituent. Transition state 9, which leads to aldol product 10, might be favored for the aldol reaction since the metal can bind to all four oxygens. The amide nitrogen of adduct 10 can then add to either face of the ketone carbonyl group to give products 6 or 7.

As expected, equilibration occurred readily at the hemiaminal center. Heating either 6a or 7a at reflux in CD3OD for 1 h afforded an equilibrium 2:1 mixture of 6a and 7a, presumably by ring opening to give the aldol adduct 10. Equilibration of either 6a or 7a with KOH in THF/MeOH for 17 h at 25 °C afforded a 6:3:1 mixture of 6a, 7a, and 8a, respectively. Isomer 8a can be formed from 6a and 7a by a retro-aldol/aldol sequence or by base-catalyzed epimerization of 10.

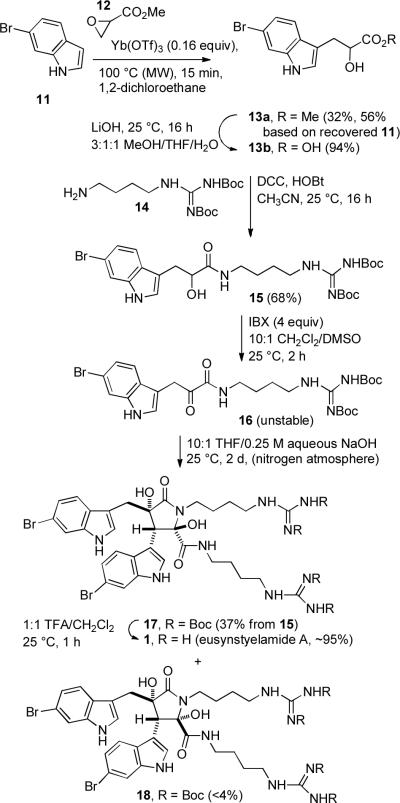

The synthesis of eusynstyelamide A (1) is shown in Scheme 3. 6-Bromoindole (11) was prepared by the Batcho-Leimgruber indole synthesis from 4-bromo-2-nitrotoluene.4 Coupling of 11 with methyl glycidate (12)5 by the procedure of Ōmura6 using 0.16 equiv of Yb(OTf)3 at 100 °C for 15 minutes in a microwave oven or at reflux for 1.5 h afforded the desired indolepropionate ester 13a in 32% yield (56% based on recovered 11) in only one step. Ōmura reported that reaction of indole, methyl glycidate, and Yb(OTf)3 (0.1 equiv) in 1,2-dichloroethane at 80 °C for 24 h afforded 52% of the hydroxy ester. The reaction with 6-bromoindole (11) proceeded in lower yield, even with more Yb(OTf)3, because the bromine is electron withdrawing and makes the indole less nucleophilic.7 Hydrolysis of the ester of 13a with LiOH in 3:1:1 MeOH/THF/H2O afforded hydroxy acid 13b in 94% yield. Coupling of acid 13b with protected agmatine 148 using DCC and HOBt in CH3CN for 16 h at 25 °C afforded hydroxyamide 15 in 68% yield. Removal of dicyclohexylurea from 15 was difficult, but initial attempts at amide formation with either EDCI and HOBt or HATU and Et3N were not promising. α-Ketoamide 5 was prepared by oxidation of the hydroxy amide with Dess-Martin reagent. This procedure didn't work well for the conversion of 15 to 16. Use of PCC or TEMPO and NaOCl was also unsuccessful. Finally, we found that oxidation9 of 15 with IBX10 in 10:1 CH2Cl2/DMSO afforded 16 cleanly. α-Ketoamide 16 is surprisingly unstable, decomposing on flash chromatography, in contrast to α-ketoamide 5 which is stable.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Eusynstyelamide A (1)

Initial attempts at carrying out the aldol dimerization of 16 with K2CO3 in acetone,11 DBU in DMF, or KOH in THF or MeOH were unsuccessful, again in contrast to the facile aldol dimerization of 5. There are significant differences between arylpyruvic acid derivatives such as 16 and saturated α-ketoacid derivatives such as 5. Saturated α-ketoacid derivatives exist only in the keto form. Conjugation with the aryl group stabilizes the enol form of arylpyruvic acid derivatives. Methyl indol-3-ylpyruvate exists as the keto form in CD3OD and mainly as the enol in CDCl3.12 Methyl phenylpyruvate exists as the enol in CDCl3 and as mixture of enol and keto forms in CD3CN.13 Other methyl arylpyruvates exist mainly in the enol form in MeOH.14 Simpkins reported that amide formation from an indol-3-ylpyruvic acid was presumably thwarted by the intervention of the enol form of the α-ketoacid.15 In contrast, α-ketoamide 16 exists in the keto form, as has been previously noted for other arylpyruvamides,16 possibly because intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the ketone and amide NH stabilizes the keto form 16K (see Scheme 4).

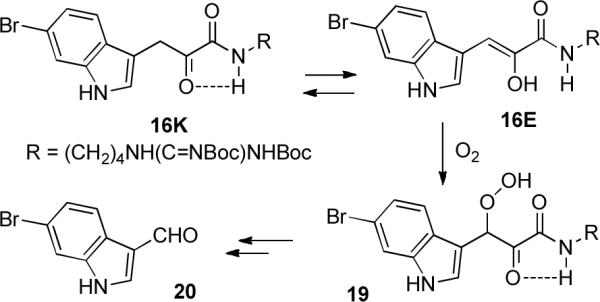

Scheme 4.

Autoxidation of α-Ketoamide 16

However, the enol form 16E is readily accessible and it, or the enolate, is readily oxidized by oxygen to 3-hydroperoxy-3-(indol-3-yl)pyruvamide 19, especially under the basic conditions needed for the aldol dimerization. The mass spectrum of fresh 16 shows a strong M+. After storage, the sample showed an M+ and an MO2+ for the hydroperoxide of equal intensity. There is limited precedent for this facile autoxidation in the literature. Autoxidation of 3-(4-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)pyruvic acid gave 3-(4-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)-2-hydroxy-3-hydroperxoycinnamic acid (the enol tautomer of the 3-hydroperoxyarylpyruvic acid).17 Radical initiated autoxidation of the enol tautomer of 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)pyruvic acid provided 3-hydroperoxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)pyruvic acid.18 Hydroperoxide 19 decomposed to give a complex mixture of products including 6-bromoindole-3-carboxaldehyde (20), a natural product19 that may be derived by a similar mechanism from 6-bromotryptophan.

Having established that the unexpected sensitivity of 16 to oxygen was causing side reactions, especially under basic conditions, we were able to successfully carry out the desired aldol dimerization under carefully controlled oxygen-free conditions. A solution of 16 in THF was carefully degassed and aqueous 0.25 M NaOH solution was added. The solution was stirred for 2 days under nitrogen to give Boc-protected eusynstyelamide A 17 in 37% yield from 15 and impure Boc-protected eusynstyelamide B 18 in <4% yield from 15). Cleavage of the four Boc groups of 17 in 1:1 TFA/CH2Cl2 for 1 h at 25 °C afforded eusynstyelamide A (1) in ~95% yield. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic 1 in CD3OD and the 1H NMR spectrum in DMSO-d6 are identical to those reported for the natural product.1

Protected anchinopeptolide D (7a), which has the same stereochemistry as eusynstyelamide B (2), readily equilibrates with 6a, which has the same stereochemistry as eusynstyelamide A (1), in CD3OD at reflux for 1 h (see Scheme 2). In contrast, Tapiolas and co-workers reported that eusynstyelamide A (1) does not equilibrate on heating in CD3OD or during prolonged storage. They also isolated mixtures of all three isomers 1–3 from some samples of E. latericius, but only eusynstyelamide A (1) from other samples. Ireland reported the isolation of only a single compound, to which he assigned the structure eusynstyelamide (4), but which is actually eusynstyelamide A (1).1 Therefore, the formation of eusynstyelamide A precursor 17 as the major isomer from 16 is consistent with the isolation of 1 as the sole isomer from some samples of E. latericius and from E. misakiensis. Eusynstyelamide A (1) does not equilibrate under the strongly acidic conditions needed to cleave the Boc groups. It is also does not equilibrate on storage in CD3OD. Extensive decomposition occurs in basic (NaOD) CD3OD.

Protected anchinopeptolide D 7a and 6a equilibrate readily, but eusynstyelamide A (1) and B (2) do not. The aldol dimerization of both 16 and 5 gave adduct 10 with high selectivity. However, hemiaminal formation afforded mainly eusynstyelamide A precursor 17 from 16 and mainly anchinopeptolide D precursor 7a, which has the same stereochemistry as eusynstyelamide B (2), from 5. The different side chains must be responsible for the differences in both the rates of equilibration and the stereochemistry of hemiaminal formation, but it is not clear why.

In conclusion, we have developed an efficient six-step route to eusynstyelamide A (1) from 6-bromoindole (11), methyl glycidate (12), and protected agmatine 14 in 13% overall yield. If oxygen is carefully excluded from the reaction, the key NaOH-catalyzed aldol dimerization of 16 proceeded efficiently to give Boc-protected eusynstyelamide A 17.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (GM-50151) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete experimental procedures, comparison of the NMR spectral data of natural and synthetic eusynstyelamide A, and copies of

1H and 13C NMR spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Tapiolas DM, Bowden BF, Abou-Mansour E, Willis RH, Doyle JR, Muirhead AN, Liptrot C, Llewellyn LE, Wolff CWW, Wright AD, Motti CA. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:1115–1120. doi: 10.1021/np900099j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swersey JC, Ireland CM, Cornell LM, Peterson RW. J. Nat. Prod. 1994;57:842–845. doi: 10.1021/np50108a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snider BB, Song F, Foxman BM. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:793–800. doi: 10.1021/jo991454l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Schumacher RW, Davidson BS. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:935–942. [Google Scholar]; (b) Konda-Yamada Y, Okada C, Yoshida K, Umeda Y, Arima S, Sato N, Kai T, Takayanagi H, Harigaya Y. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:7851–7861. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson CP, Nielsen LPC, Jacobsen EN. Org. Synth. 2006;83:162–169. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Sunazuka T, Shirahata T, Tsuchiya S, Hirose T, Mori R, Harigaya Y, Kuwajima I, Ōmura S. Org. Lett. 2005;7:941–943. doi: 10.1021/ol050077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuchiya S, Sunazuka T, Shirahata T, Hirose T, Kaji E, Ōmura S. Heterocycles. 2007;72:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indole (with a nucleophilicity N = 5.55) reacted with styrene oxide in trifluoroethanol at 80 °C for 4 h to give the alkylation product β-phenyl-1H-indole-3-ethanol in 67% yield. Under the same conditions, 5-bromoindole (N = 4.38) gave the alkylation product in only 45% yield after 72 h. The reaction of 6-bromoindole was not reported. See: Westermaier M, Mayr H. Chem.–Eur. J. 2008;14:1638–1647. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701366.

- 8.Sarabia F, Sánchez-Ruiz A, Chammaa S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:1691–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Frigerio M, Santagostino M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8019–8022. [Google Scholar]; (b) Frigerio M, Santagostino M, Sputore S, Palmisano G. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:7272–7276. [Google Scholar]; (c) De Munari S, Frigerio M, Santagostino M. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:9272–9279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frigerio M, Santagostino M, Sputore S. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:4537–4538. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braña MF, García ML, López B, de Pascual-Teresa B, Ramos A, Pozuelo JM, Domínguez MT. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:1864–1871. doi: 10.1039/b403052d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachmann S, Knudsen KR, Jørgensen KA. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:2044–2049. doi: 10.1039/b404381b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H-H, Takai T, Senda H, Kuwae A, Hanai K. J. Mol. Struc. 1998;449:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stock AM, Donahue WE, Amstutz ED. J. Org. Chem. 1958;23:1840–1848. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frebault F, Simpkins NS, Fenwick A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4214–4215. doi: 10.1021/ja900688y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González JF, de la Cuesta E, Avendaño C. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:2762–2771. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cahnmann HJ, Funakoshi K. Biochemistry. 1970;9:90–98. doi: 10.1021/bi00803a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Jefford CW, Knöpfel W, Cadby PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:6432–6436. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jefford CW, Knöpfel W, Cadby PA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:3585–3588. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Wratten SJ, Wolfe MS, Andersen RJ, Faulkner DJ. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977;11:411–414. doi: 10.1128/aac.11.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rasmussen T, Jensen J, Anthoni U, Christophersen C, Nielsen PH. J. Nat. Prod. 1993;56:1553–1558. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.