Abstract

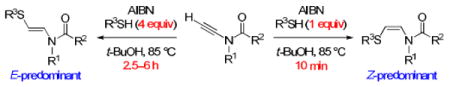

Two complementary sets of conditions for radical additions of thiols to terminal ynamides are described. The use of 1 equiv of thiol affords the cis-β-thioenamide adducts in rapid fashion (10 min) and good dr, whereas employing excess thiol and longer reaction times favors the trans products.

Ynamides are a class of compounds that have gained prominence in recent years.1 They are electron-rich alkynes,2 although their nucleophilicity can be tuned by varying the nature of the N-acyl group. Malacria has demonstrated the utility of ynamides as radical acceptors.3,4 We reasoned that they should react readily with thiyl radicals, which are electrophilic in nature.5 A recent report by Yorimitsu and Oshima detailing radical additions of arenethiols to internal tosylynamides6 lent support to this hypothesis.

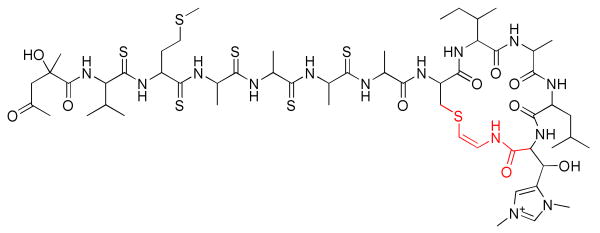

The addition of a thiyl radical to an ynamide produces a β-thioenamide. This moiety is present in unusual cyclic peptides such as thioviridamide7 (Figure 1) and the lantibiotics.8 Inspired by the striking architecture of these natural products, we investigated additions of thiyl radicals to terminal ynamides. Herein, we report the initial results of our study, which demonstrate that both cis and trans β-thioenamides can be obtained selectively by simply varying the reaction conditions.

Figure 1.

Thioviridamide (β-thioenamide highlighted in red).

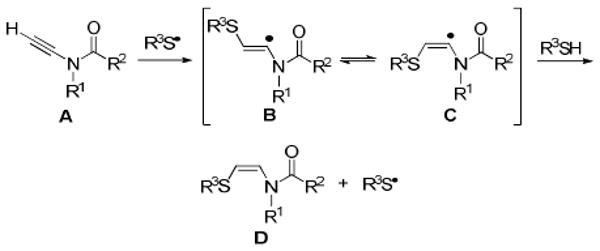

The proposed reaction is shown in Figure 2. Regioselective addition of a thiyl radical to the terminal carbon of ynamide A would provide vinyl radicals B and/or C. These intermediates would rapidly equilibrate, and hydrogen atom abstraction from the thiol by the less hindered radical C, according to the precedent of Montevecchi and co-workers,9 should afford cis-β-thioenamide D as the kinetic product. In contrast, known methods of β-thioenamide construction based on imine acylation10 or Pummerer rearrangement11 chemistry deliver predominantly the trans isomers. We also recognized that the presence of excess thiol in the reaction mixture would permit isomerization of D to the thermodynamically more stable trans isomer via a radical addition–β-thiyl radical elimination pathway.12 Accordingly, we pursued a stereoselective synthesis of both cis- and trans-β-thioenamides by seeking two complementary sets of reaction conditions.

Figure 2.

Proposed Radical Addition.

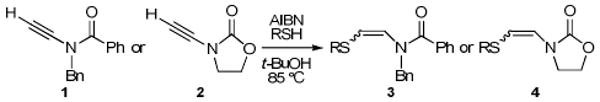

We began by studying the additions of commercially available thiols to simple ynamides. Our results are collected in Table 1. Addition of excess n-butyl thiol (4 equiv) to acyclic amide-derived ynamide 113 in refluxing t-BuOH with AIBN as initiator14 afforded β-thioenamide E-3a as the major product of a separable mixture (72%, 15:1 E:Z) after 3 h. In contrast, employing 1 equiv of thiol and 0.5 equiv of AIBN led to Z-3a in good yield (76%, 1:11 E:Z) after only 10 min. Similar trends were observed with thiophenol, although greater quantities of the E isomer were obtained under both sets of conditions. When the radical addition of tert-butyl thiol to 1 was performed under the Z-selective conditions, no reaction was observed. Subjection of this bulky thiol to the typically E-selective conditions afforded a sluggish reaction, and a modest yield (41%) of Z-3c was obtained after 6 h. Longer reaction times led to decomposition, and E-3c was never observed. There are two possible mechanisms for the formation of E-β-thioenamides: hydrogen atom abstraction from the thiol by vinyl radical isomer B (see Figure 2), and addition–elimination of thiyl radical to Z-adduct D. Both of these processes would be slowed significantly by the use of bulky thiols.

Table 1.

Additions of Simple Thiols to Ynamides 1 and 2

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSH (equiv) | equiv AIBN | time | product | % yielda | (E:Z)b |

| n-BuSH (4) | 2 | 3 h | 3a | 72 | (15:1) |

| n-BuSH (1) | 0.5 | 10 min | 3a | 76 | (1:11) |

| PhSH (4) | 2 | 5 h | 3b | 97 | (33:1) |

| PhSH (1) | 0.5 | 10 min | 3b | 33 | (1:4.3) |

| t-BuSH (4) | 2 | 6 h | 3c | 41 | (Z only)c |

| n-BuSH (4) | 2 | 3 h | 4a | 73 | (8.4:1) |

| n-BuSH (1) | 0.5 | 10 min | 4a | 72 | (1:6.0) |

| PhSH (4) | 2 | 5 h | 4b | 73 | (8.5:1) |

| PhSH (1) | 0.5 | 10 min | 4b | 74 | (1:5.1) |

| t-BuSH (4) | 2 | 6 h | 4c | 72 | (1:5.2) |

Isolated yield of the major isomer.

Determined via 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture.

The E isomer was not detected.

Thiyl radical additions to cyclic carbamate-derived ynamide 215 showed similar trends to reactions involving acyclic ynamide 1. However, the stereoselectivities of most reactions with this acceptor were attenuated, and slightly higher amounts of the minor isomers were produced under both E- and Z-selective conditions. For example, addition of tert-butyl thiol to 2 under the conditions that produced Z-3c exclusively (4 equiv thiol, 2 equiv AIBN, 6 h) provided a small amount of E-4c (1:5.2 E:Z). Importantly, E- and Z-β-thioenamides 3 and 4 were stable to SiO2 and separable via chromatography in all cases. The acyclic β-thioenamides 3 exhibited line broadening of the enamide signals in both the 1H and 13C NMR spectra, suggesting that the adducts exist in solution as a pair of slowly interconverting conformational isomers. In contrast, the corresponding signals in the spectra of cyclic adducts 4 were sharp.

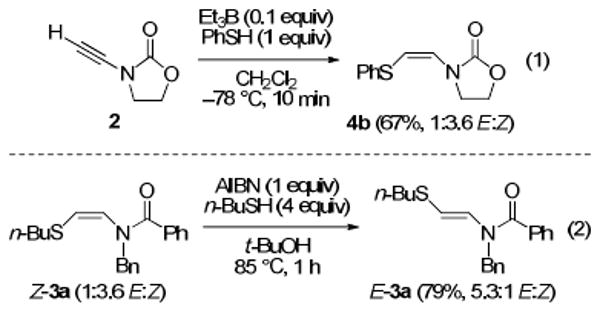

The protocol developed by Yorimitsu and Oshima for radical additions of arenethiols to internal ynamides utilizes low temperature initiation (Et3B, −78 °C).6 We wondered if the selectivity for the kinetic products Z-3 and Z-4 would improve under these conditions. Surprisingly, when the addition of thiophenol to terminal ynamide 2 was conducted in this manner, decreased selectivity for Z-4b was observed (Scheme 1, eq 1; compare to 1:5.1 E:Z, Table 1). The reasons for this result are unclear, but may be related to the difference in solvent (CH2Cl2 vs t-BuOH) or to the fact that Et3B is a Lewis acid as well as a radical initiator.

Scheme 1.

In the reactions described above, the Z adduct predominates under kinetically controlled conditions (1 equiv of thiol, short reaction times), whereas the E adduct emerges under thermodynamically controlled conditions (excess thiol, long reaction times). To confirm our suspicions that the Z adducts isomerize to the more stable E adducts under the thermodynamic conditions, we exposed enriched Z-3a to the radical addition conditions (Scheme 1, eq 2). As anticipated, we obtained a sample enriched in the E isomer in good yield.

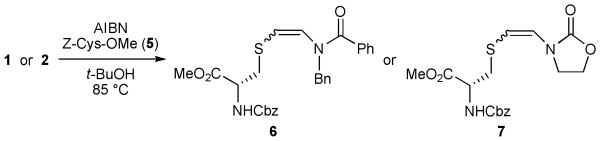

Having established the viability of radical additions of simple thiols to ynamides 1 and 2, we wished to examine the use of a thiol that would be more relevant to the construction of peptide-based β-thioenamides. Thus, we employed N-Cbz cysteine methyl ester (5) as the thiol component. Pleasingly, the E-isomer of β-thioenamide 6 was favored by using excess 5 and longer reaction times, while Z-6 was the major product with 1 equiv of 5 and shorter reaction times (Table 2). In an effort to conserve the thiol, we found that 2 equiv of 5 was sufficient to promote Z-to-E isomerization. The relatively low ratio in favor of Z-7 (1:2.9 E:Z) under kinetic conditions was surprising. Either the difference in the relative rates of formation of Z-7 and E-7 is slight, or the rate of isomerization of Z-7 is rapid enough to compete with radical addition of 5 to 2.

Table 2.

Addition of Cys-derived Thiol to Ynamides 1 and 2

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| equiv of 5 | equiv of AIBN | time | product | % yielda | (E:Z)b |

| 2 | 2 | 3 h | 6 | 68 | (8.5:1) |

| 1 | 0.5 | 10 min | 6 | 67 | (1:6.1) |

| 2 | 1 | 2.5 h | 7 | 71 | (10:1) |

| 1 | 0.5 | 10 min | 7 | 60 | (1:2.9) |

Isolated yield of the major isomer.

Determined via 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture.

In summary, we have discovered two complementary protocols for the stereoselective radical addition of thiols to terminal ynamides. Under kinetically controlled conditions, the cis-β-thioenamides are obtained in good dr (≥2.9:1, typically >5:1). In contrast, thermodynamically controlled conditions allow equilibration to the more stable trans adducts (>8:1 dr). The major isomers can be isolated in pure form via SiO2 chromatography, and the yields are good (ca. 60–80% in most cases). By enabling the selective production of either alkene isomer via selection of the appropriate conditions, this reaction provides an advantage over previously developed methods that afford trans-β-thioenamides predominantly.10,11 Thiyl radical additions to amino-acid-derived ynamides would provide access to complex peptide natural products such as thioviridamide (Figure 1). Studies directed towards this aim are currently in progress and will be the subject of future reports.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM70483) and Brigham Young University (Cancer Research Center Fellowship to J.K., CHIRP award to S.L.C.) for support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Zificsak CA, Mulder JA, Hsung RP, Rameshkumar C, Wei LL. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7575. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mulder JA, Kurtz KCM, Hsung RP. Synlett. 2003:1379. [Google Scholar]; (c) Evano G, Coste A, Jouvin K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Mulder JA, Hsung RP, Frederick MO, Tracey MR, Zificsak CA. Org Lett. 2002;4:1383. doi: 10.1021/ol020037j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Al-Rashid ZF, Hsung RP. Org Lett. 2008;10:661. doi: 10.1021/ol703083k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Marion F, Courillon C, Malacria M. Org Lett. 2003;5:5095. doi: 10.1021/ol036177q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marion F, Coulomb J, Servais A, Courillon C, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:3856. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For allenamides as radical acceptors, see: Shen L, Hsung RP. Org Lett. 2005;7:775. doi: 10.1021/ol047572z. For N-acylcyanamides as radical acceptors, see: Servais A, Azzouz M, Lopes D, Courillon C, Malacria M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:576. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602940.Beaume A, Courillon C, Derat E, Malacria M. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:1238. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700884.Larraufie MH, Ollivier C, Fensterbank L, Malacria M, Lacôte E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2178. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907237.Larraufie MH, Courillon C, Ollivier C, Lacôte E, Malacria M, Fensterbank L. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4381. doi: 10.1021/ja910653k.

- 5.(a) Ito O, Matsuda M. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:5732. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito O, Fleming MDCM. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1989;2:689. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato A, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Synlett. 2009:28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hayakawa Y, Sasaki K, Adachi H, Furihata K, Nagai K, Shin-ya K.J Antibiot 200659116568712 [Google Scholar]; (b) Hayakawa Y, Sasaki K, Nagai K, Shin-ya K, Furihata K.J Antibiot 200659616568713 [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Chatterjee C, Paul M, Xie L, van der Donk WA. Chem Rev. 2005;105:633. doi: 10.1021/cr030105v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) van der Donk WA. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9561. doi: 10.1021/jo0614240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Benati L, Montevecchi PC, Spagnolo P. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1991;1:2103. [Google Scholar]; (b) Melandri D, Montevecchi PC, Navacchia ML. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:12227. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibashi H, Kameoka C, Iriyama H, Kodama K, Sato T, Ikeda M. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Magnus P, Sear NL, Kim CS, Vicker N. J Org Chem. 1992;57:70. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishibashi H, Inomata M, Ohba M, Ikeda M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1149. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ishibashi H, Kato I, Takeda Y, Kogure M, Tamura O. Chem Commun. 2000:1527. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatgilialoglu C, Ferreri C. Ace Chem Res. 2005;38:441. doi: 10.1021/ar0400847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witulski B, Stengel T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:489. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<489::AID-ANIE489>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumdar KC, Maji PK, Ray K, Debnath P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:9124. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada T, Ye X, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:833. doi: 10.1021/ja077406x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.