Abstract

We have developed a method, MosDel, to generate targeted knock-outs of genes in C. elegans. We make use of the Mos1 transposase to excise a Mos1 transposon adjacent to the region to be deleted. The double-strand break is repaired using injected DNA as a template. Repair can delete up to 25 kb of DNA and simultaneously insert a positive selection marker.

Gene specific knockouts are a defining technology of reverse genetics, allowing phenotypes to be assigned to any of the thousands of genes identified in genome sequencing projects. In C. elegans, reverse genetics has mainly relied on random chemical mutagenesis to generate loss of function mutants1 or more recently, random deletions downstream of guanine-quadruplex DNA2. In both cases, mutagenized populations are screened by PCR with gene specific primers for random deletions in target genes. This approach has been successful in generating putative loss of function alleles in more than 5000 genes, mainly through the efforts of the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium in the U.S. and Canada, and the National BioResource Project in Japan 3,1. Random deletions have a few limitations: First, deletions are typically small and not necessarily molecular nulls. Second, chemical mutagenesis invariably leads to background mutations. And third, some deletions involve complex rearrangements1.

In fruit flies, large deficiences can be generated by recombination between FRT sites in P-elements4. Other genetic model organisms, for example yeast and mice, use transgenic DNA fragments and homologous recombination to generate targeted deletions. Bombardment with DNA-coated gold particles can lead to gene replacement in C. elegans as well5. Unfortunately, the frequency of homologous recombination is low and the technique has not been widely adopted.

Endogenous Tc1 transposons have been used in C. elegans to inactivate genes by causing random deletions after excision6. More recently the Drosophila transposon Mos1 has been adapted for gene targeting7. To facilitate the use of Mos1 elements, approximately 14,000 molecularly mapped transposon inserts were generated by the NemaGENETAG consortium8. Mobilization of transposons generates double-stranded DNA breaks; repair of the breakpoint can lead to targeted modifications when a repair template is present9. This repair mechanism was used to develop a Mos1-based technique called mosTIC7 (Mos1 excision-induced transgene-instructed gene conversion) that can be used to reliably modify DNA within one kilobase of a Mos1 insert. Building on these efforts, we developed a technique called MosSCI (Mos1-mediated single copy insertion) to insert transgenes into well-defined genomic loci10. Mos1 excision is induced using a simple injection-based method and successful insertions are identified using an inserted selectable marker10. Here, we demonstrate that Mos1 excision can be used to generate targeted deletions of up to 25 kb. We call this technique Mos1-mediated deletion (MosDel).

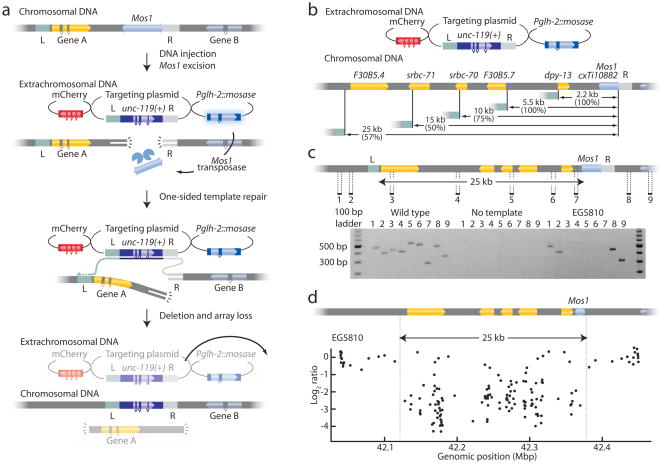

Deletions were generated in a strain with a Mos1 element adjacent to the gene of interest (Fig. 1a). The Mos1 element was excised in the germline by injection of a helper plasmid encoding the Mos1 transposase. Excision resulted in a double-strand DNA break which was repaired from the co-injected repair template. Previously we demonstrated that single copy DNA can be incorporated into the genome by flanking the DNA with homology regions from both sides of the double-strand break. Under these conditions, both free ends of the chromosome break have homologous DNA in the repair template to initiate repair. Here, we used targeting constructs capable of only one-sided repair, such that one of the broken ends has no homologous sequence to invade (Fig. 1a). Repair is initiated from one side by strand invasion of the homology arm on the template (‘R’, typically 2 kb). DNA is then copied from the extrachromosomal array, including sequence from a distal homology arm (‘L’, typically 3 kb). The 3′ end can then invade the other half of the broken chromosome at a distance from the break. A wild-type copy of the unc-119 gene is simultaneously inserted to provide a positive selection marker for deletions. Red fluorescent co-injection markers are used to visually identify animals rescued by extrachromosomal arrays so that they can be disregarded.

Figure 1. Using Mos1 transposons to create targeted deletions.

(a) Schematic of MosDel. A Mos1 transposon near the gene of interest is placed into an unc-119(ed3) strain. Injection of a plasmid encoding Mos1 transposase (Pglh-2::mosase) results in excision of the transposon. The resulting double-strand DNA break is repaired by synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) at the right homologous region (R) on the extrachromosomal targeting plasmid, incorporating the positive selection marker unc-119(+) into the chromosomal locus. Genomic DNA between the right and left (L) homology regions is deleted when the nascent repair-strand re-invades the genomic DNA and resolves the break by homologous recombination. Red fluorescent co-injection plasmids (mCherry) mark the extra-chromosomal array; deletion mutants are isolated by screening for unc-119 rescued worms lacking mCherry fluorescence. Pglh-2::mosase, mCherry and the targeting plasmid are injected as separate plasmids. (b) Schematic of deletions generated at the Mos1 insertion cxTi10882(IV). Targeting efficiency (successful deletions per unc-119 insertion) is indicated in parentheses. (c) Schematic of the 25 kb deletion. PCR oligos were designed to amplify 200–500 bp fragments outside and inside the targeted region (labeled 1–9). PCR validation of a successful deletion is shown; amplification of genomic DNA is only possible outside the targeted regions. (d) Comparative genome hybridization (CGH) verification. EG5810 (25 kb deletion) and wild-type DNAs were hybridized to a C. elegans specific CGH chip12. A log2 ratio below -2 indicates deleted DNA. Points within the deletion showing normal hybridization are likely due to nonspecific DNA binding.

To test the targeting strategy we selected a Mos1 element (cxTi10882) located 1.1 kb 3′ from dpy-13 (Fig. 1b). dpy-13 mutants are viable and can be identified based on the dumpy phenotype. We injected 83 unc-119 cxTi10882 worms with a targeting plasmid that deleted the full dpy-13 coding region (2.2 kb deletion) and inserted a GFP marker expressed in coelomocytes and the unc-119(+) selection marker. After two generations (one week), plates were screened visually for the presence of unc-119(+) worms that lacked the co-injection markers. We identified three putative deletion strains (3/83 injected worms = 3.7 %). Each strain was homozygous for dpy-13 mutations, the unc-119(+) marker and expressed GFP in coelomocytes; the 2.2 kb deletion was confirmed by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

In most organisms, the efficiency of transgene-instructed gene conversion drops rapidly with distance from the DNA breakpoint; only 25 % of conversions extend 1 kb from the breakpoint7,11. To determine how much DNA could be feasibly deleted using MosDEL, we injected additional constructs coding for 5 kb, 10 kb, 15 kb, 25 kb, 35 kb and 50 kb deletions (Fig. 1b). The frequency of unc-119(+) insertion was largely independent of the targeting construct: rescued strains were found in the progeny of about 5 % of the injected animals (Supplementary Table 1). For example, we isolated 7 stable lines with unc-119(+) insertions from 81 injected animals (9 %) using the 25 kb construct. Two of the lines did not exhibit a Dpy phenotype and thus are simply insertions of the unc-119(+) transgene. Five strains exhibited a Dpy phenotype. One of these five did not delete the entire 25 kb stretch, whereas the other four were deletions of the entire 25 kb region (4/7 lines = 57 % deletions correct) based on PCR analysis (Fig. 1c) However, the generation of deletions decreased sharply for events larger than 25 kb: full-length deletions were not recovered using the 35 kb and 50 kb templates (Supplementary Table 1). For these larger deletions, all unc-119(+) insertions (13 strains) were incomplete deletions (data not shown).

We used comparative genome hybridization (CGH) to verify deletion endpoints and confirm PCR results. In CGH, fluorescently labeled mutant DNA is compared to binding of wild-type DNA on a high-density array of gene specific oligonucleotides12. CGH analysis verified the deletion of the targeted genomic regions in the three strains tested: a 25 kb deletion (Fig. 1d) and two 15 kb deletions (data not shown).

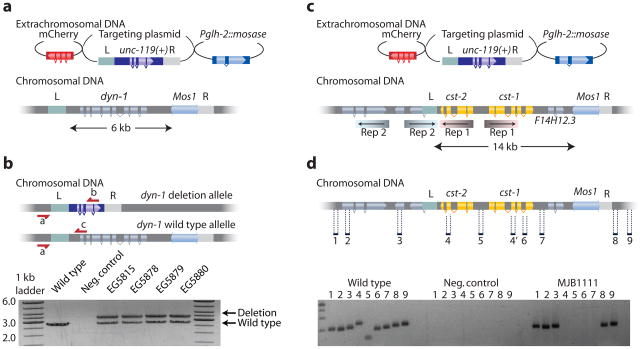

Deletion of essential genes will be lethal when homozygous. Such deletions must be maintained as heterozygotes over a balancer chromosome; the balancer chromosome usually contains a marker that identifies loss of heterozygosity. Balanced strains often degenerate due to recombination between the marker and deletion on the homologous chromosomes. MosDel leads to perfectly balanced lethal chromosomes by inserting a selectable marker (unc-119(+)) at the site of the deletion. Rescue of the unc-119(−) uncoordinated phenotype identifies the presence of the deletion in heterozygotes. Because unc-119 animals are sub-viable, the homozygous balancer animals are selected against, and the deletion chromosome is maintained as a heterozygote. To demonstrate the utility of this feature, we deleted the entire coding region of the C. elegans dynamin ortholog dyn-1 (Fig. 2a). From 100 injected animals we obtained 17 strains that were unc-119(+) and did not contain extra-chromosomal arrays based on the absence of red fluorescent co-injection markers. 11 of 17 strains (65 %) could not be homozygosed for the unc-119(+) marker as expected from a lethal mutation balanced by the insertion of unc-119(+). Five of these 11 were selected for further verification. PCR analysis confirmed that four of five strains contained the full targeted deletion (Fig. 2b) and lethality could be rescued by a dyn-1(+) transgene.

Figure 2. Deleting lethal genes and multiple similar genes.

(a) Schematic for the deletion of the essential gene dynamin dyn-1. (b) Schematic showing the balanced heterozygous deletion mutant. The dyn-1 deletion allele is balanced with the insertion of unc-119(+). Below is shown the PCR verification of the deletion on heterozygous strains with the three oligos (a, b and c) shown in the schematic. (c) Schematic showing the cst-1 and cst-2 genomic region. cst-1 and cst-2 are 100 % identical in the inverted repeats (“Rep1”) indicated by shaded coloring. An adjacent region contains a second inverted repeat (“Rep2”), which overlaps the left homology region (“L”). The targeting construct removes 14 kb of genomic DNA, including cst-1, cst-2 and the gene F14H12.3 (d) PCR verification of successful deletions of cst-1, cst-2 and F14H12.3. Oligos were designed to amplify 200–300 bp fragments inside and outside the deletion.

Occasionally, the genome contains tandem gene duplications that provide redundant function or operons encoding genes with related functions. The loss of function phenotype of such loci requires the deletion of both genes, which can be accomplished using MosDel. To demonstrate this application, we targeted the two protein kinase genes cst-1 and cst-2 (Fig. 2c). These genes are adjacent to each other as two identical inverted repeats in a complex genomic region. We designed a deletion template for these two genes and isolated two strains containing unc-119(+) insertions; of these, one strain contained the correct deletion (Fig. 2d).

These results show that MosDel can be used to target a gene if there is a Mos1 insertion within 25 kb of the gene. This method has a number of advantages relative to current knock-out techniques: First, the technique is relatively fast and efficient. Second, the end-points of deletions can be specified to completely eliminate the gene so no partial gene products are generated. Third, lethal mutations are balanced by the positive insertion marker. In cases where alleles do not have an obvious phenotype a GFP marker can be inserted to follow the mutation in crosses. Finally, several adjacent genes can be deleted. This is particularly useful when genes with similar function are grouped.

The technique relies on the prevalence of Mos1 insertions in the genome. We analyzed the distribution of the 14,305 Mos1 elements relative to all 20,160 genes in C. elegans. Of these, 20,043 genes (99.4 %) fall within 25 kb of at least one Mos1 element (median distance 3.1 kb to nearest Mos1), so essentially all C. elegans genes can be targeted by MosDel (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, 10,069 of 10,154 genes presently lacking a deletion allele can be deleted by MosDel. Moreover, 8,803 genes have no other genes between them and the Mos1 element so these gene can be removed as a single gene deletion.

Plasmid-mediated repair of double-strand breaks is not limited to C. elegans. For example, in Drosophila plasmid-driven repair has have been described13 and the technique could possibly be adapted to make deletions in fruit flies too. This technique should be a useful tool for the C. elegans research community and possibly for other genetic model organisms.

Methods

Nematode strains

Mos1 alleles were selected by visual screening in Wormbase (www.wormbase.org) for appropriately located transposon insertions and provided by the NemaGENETAG consortium. Mos1 insertions were homozygosed and followed in crosses by PCR. Strains were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 or HB101 bacteria.

Strains with Mos1 elements and all deletions generated are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Deletion protocol

Mos1 alleles were identified in Wormbase (www.wormbase.org) and requested from the NemaGENETAG consortium (http://elegans.imbb.forth.gr/nemagenetag/). The presence of the Mos1 insertion was verified with gene-specific primers, annealing inside and outside of the Mos1 element. The Mos1 element was crossed into the unc-119(ed3) background to make an injection strain and verified by PCR analysis.

Targeting constructs were designed to contain (1) a right homology region (adjacent to the Mos1 element, (2) a left homology region (distant from the Mos1 element) and (3) a C. briggsae-unc-119(+) rescue region. The ‘right’ homology regions were comprised of approximately 2.0 kb of homologous DNA immediately adjacent to the Mos1 insertion site. The ‘left’ homology regions were comprised of 2 to 3 kb of homologous DNA, which specifies the endpoint of the targeted deletion. These regions were selected to avoid repetitive DNA sequences, in particular short inverted repeats, which are likely to anneal and reduce the frequency of correct deletions. DNA between the ‘right’ and ‘left’ homology region is deleted; DNA contained in the ‘left’ region is retained in the deletion strain. A C. briggsae unc-119(+) rescue fragment was chosen because it is smaller than the C. elegans unc-119 gene.

An injection mix was made that contained the targeting plasmid (50 ng/ul), Mos1 transposase helper plasmid pJL43.114 (50 ng/ul), mCherry co-injection markers pGH810 (Prab-3::mCherry, 10 ng/ul), pCFJ9010 (Pmyo-2::mCherry, 2.5 ng/ul), and pCFJ10410 (Pmyo-3::mCherry, 5 ng/ul). The injection strain was maintained at 15°C on HB101 bacteria. Young adult animals were mounted on an agarose pad under halocarbon oil and injected following standard techniques. Injected worms were left to recover at 15°C for a couple of hours and then transferred three at a time to HB101 or OP50 seeded NGM plates and placed at 25°C. In our hands, approximately 70 % of all injected worms resulted in transgenic progeny. We found that growing worms on HB101 bacteria at 15°C significantly improved the health of unc-119 animals.

After approximately 7 days each plate was screened for deletion mutants. Screening was greatly facilitated by allowing the plate to starve out completely because unc-119 animals cannot form dauers and are therefore selected against. Strains with an unc-119(+) insertion were identified on a fluorescence dissection microscope as L1 animals that move like wild-type animals but have none of the fluorescent co-injection markers. A single rescued, non-fluorescent animal was picked to a new plate and allowed to propagate for one generation. In the case of obvious phenotypes (for example, Dpy-13) a single mutant animal was picked from the progeny; in cases where the phenotype was wild-type ten animals were picked to individual plates and tested for homozygosity.

It takes approximately two weeks from injecting the strain to recovering a homozygous deletion animal.

Analysis of Mos1 distribution

We calculated the distance of every protein coding gene in the WS205 referential release of WormBase (http://ws205.wormbase.org15) to all current Mos1 insertion alleles using a state machine algorithm written in Perl. The closest Mos1 element was defined as the distance from the insertion site to the ATG start codon. The number of Mos1 elements in the vicinity of each gene was determined by extracting a sequence segment upstream and downstream of the ATG and summing the number of elements contained within that span. The number of intervening genes between a given gene and its nearest Mos1 element was determined by extracting the segment ranging from the ATG to the insertion site and tallying the number of genes present, including genes that partially reside within the interval. The analysis was repeated against all genes lacking a deletion allele from either the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium in the U.S. and Canada (ok alleles) and the National BioResource Project in Japan (tm alleles).

Comparative Genome Hybridization

Genomic DNA from worms was isolated with the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s supplementary protocol: “Purification of archive-quality DNA from nematodes or nematode suspensions using the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit”. DNA labeling, sample hybridization, image acquisition, and determination of fluorescence were all performed as previously described12. We used a 3x high-density (HD) chip divided into three 720 K whole genome sections for all experiments. The chip design was based on our original 385 K whole genome chip12. All microarrays were manufactured by Roche-NimbleGen with oligonucleotides synthesized at random positions on the arrays. Chip design name is 90420_Cele_RZ_CGH_HX3. For all experiments, normalization of intensity ratios were performed with a LOESS regression as previously described12. Three strains, EG5810 (25 kb deletion), EG5620 (15 kb) and EG5621 (15 kb), were tested against wild-type DNA. All strains showed the targeted deletions. All samples also showed two identical untargeted deletions: an approximately 8 kb deletion of pgp-6 and pgp-7 on chromosome X and an approximately 4 kb deletion of the telomeric region cTelX3.1 at the left end of chromosome V. We verified by CGH that these deletions were present in the parent strain (EG5003) and the deletions therefore do not represent second site mutations caused by the MosDEL technique.

Molecular biology

Targeting vectors typically consist of three distinct fragments: a ‘right’ homology region, a positive selection marker (cb-unc-119(+)) and a ‘left’ homology region. In some cases the positive selection marker was flanked by the fluorescent marker Punc-122::GFP, which is dimly expressed in the coelomocytes. See Figure 1a for a schematic overview of the components of the targeting vector. All targeting vectors were made using the MultiSite Gateway Three-Fragment Vector Construction Kit (Invitrogen, Catalog no. 12537-023).

To verify deletions by PCR we designed oligos that would amplify short genomic DNA fragments inside and outside the targeted regions. These reactions were reproducible and robust; PCR amplification was successful on crude genomic lysates from 5–10 worms or from high quality DNA samples prepared with a Gentra Puregene Kit (Qiagen).

dyn-1 heterozygous verification primers: Complete dyn-1 deletions were verified at the 5′ end by PCR amplification with the three primers: oGH154, oGH133 and oCF125. Oligos oGH154 + oGH133 give a 2.7 kb PCR product when the wild-type copy of dyn-1 is present. Oligos oGH154 + oCF125 give a 3.4 kb PCR product when the dyn-1 locus is deleted.

The deletion was verified at the 3′ end by PCR with oligos oGH155, oGH156 and oCF400. Oligos oGH155 + oGH156 produce a 2.5 kb PCR product when the wild-type dyn-1 locus and the ttTi14024 Mos1 element are present.

Oligos oGH155 + oCF400 produce a 3.0 kb PCR product when the dyn-1 gene is deleted.

All molecular biology analysis and design was done with the program ApE (A plasmid Editor) that is freely available at http://www.biology.utah.edu/jorgensen/wayned/ape/.

All oligos and plasmids are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. PCR verification of dpy-13 deletion.

Supplementary Figure 2. Mos1 distribution in the genome.

Supplementary Table 1. Deletion frequency

Supplementary Table 3. Strains, plasmids and oligos

Supplementary Table 2. Mos1 Distribution. (Note: Large dataset, too large to include in joined PDF file.)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank L. Segalat (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Lyon) and the NemaGENETAG consortium for Mos1 strains. C.F.-J. is funded by a fellowship from the Lundbeck Foundation and G.H. from a Jane Coffin Childs fellowship funded by Howard Hughes Medical Institute. E.M.J. is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.B. is funded by a McKnight Grant. D.G.M. is funded by Genome Canada and Genome B.C.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

C.F.-J., M.W.D., G.H. and E.M.J. conceived and designed experiments; C.F.-J., G.H., J.T., P.N., R.L. and M.P.-D. performed experiments; TH performed the bioinformatic analysis of Mos1 distribution; M.B., D.G.M. and E.M.J. provided supervision and funding; C.F.-J. and E.M.J. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Moerman DG, Barstead RJ. Towards a mutation in every gene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2008;7:195–204. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pontier DB, Kruisselbrink E, Guryev V, Tijsterman M. Isolation of deletion alleles by G4 DNA-induced mutagenesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:655–657. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gengyo-Ando K, Mitani S. Characterization of mutations induced by ethyl methanesulfonate, UV, and trimethylpsoralen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:64–69. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryder E, et al. The DrosDel deletion collection: a Drosophila genomewide chromosomal deficiency resource. Genetics. 2007;177:615–629. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.076216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berezikov E, Bargmann CI, Plasterk RHA. Homologous gene targeting in Caenorhabditis elegans by biolistic transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwaal RR, Broeks A, van Meurs J, Groenen JT, Plasterk RH. Target-selected gene inactivation in Caenorhabditis elegans by using a frozen transposon insertion mutant bank. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7431–7435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert V, Bessereau J. Targeted engineering of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome following Mos1-triggered chromosomal breaks. EMBO J. 2007;26:170–183. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazopoulou D, Tavernarakis N. The NemaGENETAG initiative: large scale transposon insertion gene-tagging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetica. 2009;137:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s10709-009-9361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plasterk RH, Groenen JT. Targeted alterations of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome by transgene instructed DNA double strand break repair following Tc1 excision. EMBO J. 1992;11:287–290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frøkjaer-Jensen C, et al. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gloor GB, Nassif NA, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Preston CR, Engels WR. Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila via P element-induced gap repair. Science. 1991;253:1110–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1653452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maydan JS, et al. Efficient high-resolution deletion discovery in Caenorhabditis elegans by array comparative genomic hybridization. Genome Res. 2007;17:337–347. doi: 10.1101/gr.5690307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeler KJ, Dray T, Penney JE, Gloor GB. Gene targeting of a plasmid-borne sequence to a double-strand DNA break in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:522–528. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bessereau JL, et al. Mobilization of a Drosophila transposon in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line. Nature. 2001;413:70–74. doi: 10.1038/35092567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris TW, et al. WormBase: a comprehensive resource for nematode research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. PCR verification of dpy-13 deletion.

Supplementary Figure 2. Mos1 distribution in the genome.

Supplementary Table 1. Deletion frequency

Supplementary Table 3. Strains, plasmids and oligos

Supplementary Table 2. Mos1 Distribution. (Note: Large dataset, too large to include in joined PDF file.)