Abstract

Dengue fever (DF), a public health problem in tropical countries, may present severe clinical manifestations as result of increased vascular permeability and coagulation disorders. Dengue virus (DENV), detected in peripheral monocytes during acute disease and in in vitro infection, leads to cytokine production, indicating that virus–target cell interactions are relevant to pathogenesis. Here we investigated the in vitro and in vivo activation of human peripheral monocytes after DENV infection. The numbers of CD14+ monocytes expressing the adhesion molecule intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) were significantly increased during acute DF. A reduced number of CD14+ human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR+ monocytes was observed in patients with severe dengue when compared to those with mild dengue and controls; CD14+ monocytes expressing toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 were increased in peripheral blood from dengue patients with mild disease, but in vitro DENV-2 infection up-regulated only TLR2. Increased numbers of CD14+ CD16+ activated monocytes were found after in vitro and in vivo DENV-2 infection. The CD14high CD16+ monocyte subset was significantly expanded in mild dengue, but not in severe dengue. Increased plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin (IL)-18 in dengue patients were inversely associated with CD14high CD16+, indicating that these cells might be involved in controlling exacerbated inflammatory responses, probably by IL-10 production. We showed here, for the first time, phenotypic changes on peripheral monocytes that were characteristic of cell activation. A sequential monocyte-activation model is proposed in which DENV infection triggers TLR2/4 expression and inflammatory cytokine production, leading eventually to haemorrhagic manifestations, thrombocytopenia, coagulation disorders, plasmatic leakage and shock development, but may also produce factors that act in order to control both intense immunoactivation and virus replication.

Keywords: activation markers, dengue, monocytes, patients, severity

Introduction

Dengue fever (DF) has been a health problem in Brazil since the 1980s and its incidence has gradually increased, alarming authorities after the identification of Dengue virus 3 (DENV-3) in 20001 and re-introduction of Dengue virus 2 (DENV-2) in 2008. The last change of serotype predominance in the Rio de Janeiro State led to a huge epidemic and increased severity of DF in children, resulting in about 230 000 notifications of the disease.2

After DENV infection individuals may develop an acute febrile illness that is accompanied by debilitating headache and myalgia.3 In some instances a life-threatening syndrome may occur with characteristics of a haemorrhagic fever or shock syndrome. It is well accepted that dengue is a disease that has immunopathological patterns, with up-regulation of inflammatory molecules and immunological cells probably playing a role in coagulation disorders and increased vascular permeability, resulting in the abnormal homeostasis observed in the disease. These phenomena may be crucial to the severity assessment.4,5

Pathogenesis may consist of virus penetration into monocytes and dendritic cells, cell activation and induction of cytokines, arachdonic acids and very probably nitric oxide (NO), which may all act systemically. Considering that dengue is an acute and short-term disease, factors such as interferon (IFN)-α and -β, NO and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α probably inhibit DENV replication, although inflammatory reactions may also be activated.6 During DF, circulating inflammatory cytokines produced by monocytes and dendritic cells may activate coagulation factors and endothelial cells. Although it is known that a series of cytokines are probably involved in inducing these events, the molecular mechanisms involved have not been completely elucidated.7

Blood monocytes have been divided in two major subsets: classical and pro-inflammatory. These cells have been shown to exhibit distinct phenotypes and functions.8 Classical monocytes are strongly positive for the CD14 cell-surface molecule (CD14+ CD16−), while the CD14+ CD16+ subset co-expresses CD16 and low levels of CD14. CD14+ CD16+ cells are a unique monocyte type: some have a low or a high intensity of CD14 expression, are frequently named as CD14low CD16+ and CD14high CD16+, respectively, and have already been well characterized in peripheral blood. The CD14low CD16+ cells have been described as pro-inflammatory, producing high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR expression and few anti-inflammatory cytokines.9 Upon lipopolysacharide (LPS) stimulation, the CD14low CD16+ cells produce more TNF-α than any other well-characterized population and little interleukin (IL)-10. The other population, the CD14high CD16+ cells, were shown to increase in parallel to CD14low CD16+ in the sepsis course; they express haemoglobin scavenger receptor – CD163 – and, in particular, these cells were found to be the main producers of IL-10, showing an anti-inflammatory pattern.10

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are important in microbial recognition,11 mainly by binding to molecules called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and by activating relevant pathways after viral infection. They may be involved in the induction of antiviral molecules, such as interferon, and may also be implicated in the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which probably exert immunopathological functions.12

In this study, we report that patients with DF presented with an increase in the numbers of monocytes expressing TLRs, CD16 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) molecules. Patients with severe DF showed a decrease in the mean fluorescence intensity of HLA-DR cells. Considering that TLRs may be involved in activating pro-inflammatory cytokines, we aimed to determine here the innate immune response induced by monocyte–DENV interaction that may result in relevant changes leading to immunopathology after infection with the virus in vitro or natural infection in vivo. Our results indicate that monocytes may play crucial roles during dengue disease and we suggest that these alterations may have implications for immunopathogenesis, resulting in coagulation disorders and/or in the induction of vascular permeability.

Materials and methods

Study population and blood samples

From 2001 to 2002 and in 2008 during the outbreaks of DENV-1 and DENV-3, respectively, heparinized peripheral blood samples were obtained from 50 dengue-infected patients (18 female subjects and 32 male subjects; age range 15–73 years), who attended two health centres in the state of Rio de Janeiro. We considered as severe dengue all patients with thrombocytopenia (< 100 000 counts/mm3) and hypotension (postural hypotension with a decrease in the systolic arterial pressure of 20 mmHg in the supine position or a systolic arterial pressure of < 90 mmHg). We observed that among dengue patients, 26 had platelet levels of ≥ 100 000 counts/mm3, without hypotension, and they were therefore classified as having mild dengue; 24 other patients had thrombocytopenia and hypotension, successively receiving parenteral hydration for at least 6 hr, and were classified as having severe dengue [not necessarily meeting the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for dengue haemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS)] according to other, earlier, studies in adults.

As other investigators have previously reported,3–15 we also were unable to meet the WHO criteria16 for severity classification. We based our criteria on the report of Harris et al.,15 who studied a group of Nicaraguan patients with severe dengue, who had signs of shock that did not fit the DHF/DSS classification, and designated this disease category as dengue with signs associated with shock. Other studies support an alternative classification for severity of dengue in adults.17–19

No fatal cases were included in the present study. Fifteen age-matched healthy individuals (nine women, six men, 18–50 years) were included as controls and presented no febrile symptoms or other apparent illnesses in the previous 3 months.

The diagnosis of DENV infection was confirmed by anti-dengue enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) IgM,20 serotype-specific reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or by virus isolation.21 The immune response to dengue was considered as primary or secondary by IgG ELISA, according to previously established criteria.22

Procedures performed during this work were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazilian Health Ministry (recognized by the Brazilian National Ethics Committee) registered with the Number 111/00.

Purification and cryopreservation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy individuals and dengue-infected patients were obtained from 30 ml of heparinized venous blood. Blood samples were diluted 1 : 1 with the culture medium RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and PBMC were isolated by layering the cells onto a Ficoll–Paque™ (d = 1·077 g/ml; Amersham Biosciences Corp, Piscataway, NJ) gradient and centrifugation at 400 g for 30 min. The PBMC layer was washed twice in RPMI-1640. The viability of PBMCs was > 95% after Trypan Blue exclusion. Approximately 106 PBMCs were resuspended in 1 ml of solution destined for freezing [90% inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco, Invitrogen) plus 10% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO)] and stored initially at −70° for 24 hr before introduction into liquid nitrogen, and aliquots were cryopreserved for later study.

Reagents and monoclonal antibodies

The mouse anti-human surface antigen monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used in this study were labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE) or cycrome (Cy) and included: anti-CD14 mAb (IgG1), anti-HLA-DP, -DQ, -DR mAbs (IgG1), anti-CD16 mAb and anti-CD11c (IgG2a) from DAKO (Copenhagen, Denmark); anti-TLR2 mAb (IgG1), anti-TLR4 mAb (IgG1), anti-TLR8 mAb (IgG1) and TLR3 mAb (IgG1) from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); as well as anti-CD54 mAb (IgG1) from Caltag (Carlsbad, CA), and mAb Dengue Complex-reactive (IgG2a) from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-mouse IgG was labelled with PE or FITC from DAKO. A matching isotype control for each antibody was included in all experiments.

Cell line cultures

The Aedes albopictus C6/36 cell clone was grown as monolayers at 28° on Leibovitz medium (L-15) (Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with 200 mm glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 19% tryptose phosphate broth, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 10 μg/ml of streptomycin and 5% FCS.

Preparation of virus stock and virus titration

DENV serotype 2, strain 16681, was provided by Dr S. B. Halstead (Naval Medical Research Center, Silver Spring, MD). Virus was titrated by serial-dilution cultures in microtitre plates and detected by immunofluorescence, as previously described.23 Briefly, virus stock was prepared from infected C6/36 cells as described above. After removal of cell debris by centrifugation, the supernatant was stored at −70°, after which the viral titre was determined. The virus titre was calculated as 50% tissue culture infectious dose per ml (TCID50/ml). Inactivated virus was prepared by incubating the inoculum for 30 min at 56°. Virus stock used was at a final culture concentration of 1·37 × 108 TCID50/ml.

Preparation of human PBMCs

PBMCs were obtained from heparinized venous blood originating from adult donors. Cells were isolated through density-gradient centrifugation (400 g, 30 min in Ficoll–Paque). Cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 200 mm glutamine (Gibco, Invitrogen), 100 U/ml of penicillin (Gibco, Invitrogen), 10 μg/ml of streptomycin (Gibco, Invitrogen) and afterwards incubated at 37° under a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 2 hr for monocyte enrichment. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and adherent cells were recovered by scratching into cold medium.

Adherent PBMC infection and population characterization

Enriched monocytes were suspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and seeded at 1 × 106 cells/ml on 24-well plates. After 18 hr of incubation, infection was performed using diluted inoculum (250 μl) in medium containing 1·37 × 108 TCID50/ml. After 2 hr of incubation for adsorption, cell culture supernatant was replaced with medium containing 10% FCS and further incubated for up to 6 days. Wells were set in triplicate for each different parameter in culture. Cell viability was determined in culture, daily, by Trypan Blue exclusion. Cells incubated with medium, or inactivated or infectious DENV, were assayed.

Cells in culture were recovered by scratching with a plastic microtip into cold medium and were set at 1 × 106 cells per microtube; they were centrifuged (350 g, 5 min) and washed once with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·4, with 2% FCS and 0·01% NaN3. Surface labelling was performed with FITC- or PE-labelled antibodies to CD14 (DAKO; 1 : 100 dilution) for 30 min directly on adherent viable PBMCs placed in an ice bath. This procedure confirmed that ∼95% of the monocyte gated cells were CD14+ on the day of infection.

Limulus amebocyte lysate test for LPS detection

Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) detection was tested on samples of plasma from 23 patients with dengue in whom TLR expression was assayed. To inactivate plasma proteins, plasma samples were diluted 1 : 5 in endotoxin-free water and heated to 65° for 30 min. The LPS content was measured using a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay from LONZA (Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A positive reaction was recorded by the formation of a firm gel that remained intact momentarily when the tube was inverted. A negative reaction was recorded by the absence of a solid clot after inversion.

Extracellular and intracellular labelling for flow cytometry analysis

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and divided into aliquots, each containing 2 × 105 cells, and labelled for flow cytometry analysis. Fresh cells were recovered from cultures as described above. Both in vitro monocytes infected or monocytes from patients were labelled extracellularly and intracellularly according to previously described methods,24 with slight modifications.

Cells were washed with PBS, pH 7·2, supplemented with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0·1% NaN3 (Sigma) (PBS-BSA-NaN3) and incubated for 20 min on ice with blocking buffer consisting of 1% BSA, 5% autologous plasma and 0·1% NaN3. Then, PBMCs were washed in PBS-BSA-NaN3 and double-stained or triple-stained with specific mAbs (anti-TLR2, anti-TLR4 and anti-CD14) for 30 min at 4° in dilutions recommended by the manufacturer. Labelled cells were then washed in PBS-BSA-NaN3 and fixed in PBS-BSA-NaN3 containing 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 min at 4° for intracellular labelling; membrane permeabilization was carried out with 1 ml of PBS containing 0·1% saponin with 2% FCS and 0·01% NaN3 and further labelled with Alexa 654-labelled mAb to DENV for 30 min. Finally, cells were washed twice, resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde and kept at 4° for up to 24 hr until acquisition by flow cytometry. Cells were acquired (10 000 for gated monocytes) on a FACS®Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysed using FlowJo Software version 4.3 (TreeStar Inc., San Diego, CA). Isotype-matched antibodies were used as a negative control for all labelling procedures.

Cytokine detection plasmas from dengue patients

Plasma samples were obtained from 43 patients with dengue and from 15 controls and stored in aliquots at −70° until use. Soluble factors IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α were detected in the plasma samples using a multiplex biometric immunoassay, containing fluorescent dyed microspheres conjugated to a mAb specific for a target protein, used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Plex Human Cytokine Assay; Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA) and previous descriptions.19 The plasma levels of IL-18 were determined using an ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

In order to determine significant differences in cell-surface markers and cytokines during DENV in vitro infection and to compare different patient groups, data that passed the normality test were submitted to one-way analysis of variance (anova) followed by Turkey’s multiple comparison test. A two-way Student’s t-test was performed in order to determine the significance of differences in the percentages of virus-labelled cells obtained under various culture conditions. For non-parametric data sets, the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test was applied. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to evaluate variations in the expression of cell-surface markers between patients and control donors. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the incidence of primary and secondary infection. Altered parameters were considered to be associated with statistically significant P-values when the P-value was < 0·05. Prism version 4.02 for Windows (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA) was used to calculate statistical significance.

Results

Clinical and laboratory characterization of adult Brazilian patients with DF

Among the 50 patients with acute DF investigated in this study, leucopoenia was present in 64% and thrombocytopenia in 47%. Only five patients among 22 with mild dengue and 12 among 22 patients with severe dengue were classified as having a secondary infection. Subjects with secondary DENV infection were more likely to be experiencing severe DF, although no statistical significance for this was found in Fisher’s exact test (P = 0·0618). It was also determined that 26 patients had platelet counts of ≥ 100 0000/mm3, no significant changes of arterial pressure and no severe haemorrhagic manifestations, and they were therefore classified as having mild dengue. Another 24 patients had thrombocytopenia (platelet levels of < 100 0000/mm3) and arterial or postural hypotension, and had received parenteral hydration for at least 6 hr; these patients were classified as having severe dengue, matching previous criteria used for adults in South and Central America.17–19

Monocyte activation during acute DF

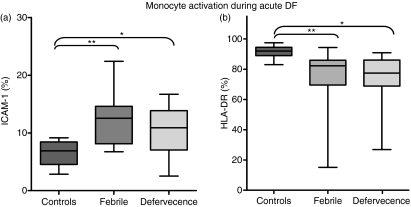

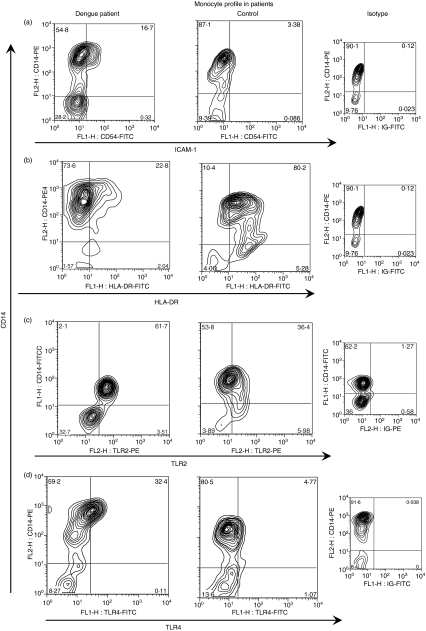

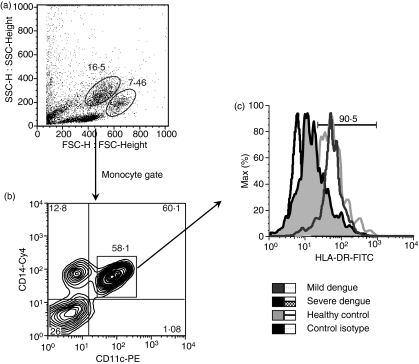

We evaluated the monocyte-expressed molecule ICAM-1 (CD54), known to mediate adhesive interactions among leucocytes, endothelial cells and matrix proteins, and observed that ICAM-1 is up-regulated mainly in CD14+ monocytes in patients with dengue. There was a significantly higher mean percentage of cells expressing ICAM-1 (CD54+) among total monocytes (CD14+) in dengue patients than in cells from healthy individuals (controls versus dengue patients with fever, P = 0·0012; and at defervescence, P = 0·0288; Figs 1a and 2a). No differences in cell subsets were found between febrile and defervescence stages or between primary and secondary infection. Further analyses were performed to provide additional knowledge of the role of CD14+ monocytes in the course of DENV infection. The HLAs grouped as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes – HLA-DP, -DQ, -DR – expressed on monocytes from dengue patients and healthy individuals, were analysed by flow cytometry. The mean percentage of CD14 monocytes expressing HLA-DR was lower in dengue patients than in healthy individuals (controls versus febrile, P = 0·0058; or versus defervescent dengue patients, P = 0·0014; Figs 1b and 2b). Interestingly, the mean percentage of CD14 monocytes expressing HLA-DR was also lower in dengue patients with secondary infection than with primary infection (66 ± 23%, n = 17 and 78 ± 13%, n = 28, respectively; P = 0·0342). To ensure that the analysis had been performed only in the monocyte population, and to exclude the possibility of contamination with non-monocyte cell subsets expressing CD14, we performed a triple-labelling to CD14, HLA-DR and CD11c surface molecules. Figure 3c is representative for HLA-DR expression on gated CD14+ CD11c+ monocytes from a control donor, and from patients with mild dengue and severe dengue. The mean percentage of HLA-DR expression among CD14+ CD11c+ monocytes was significantly lower in patients with severe dengue than in patients with mild dengue (controls 94 ± 2%, n = 2; mild dengue 95 ± 3%, n = 4; and severe dengue 71 ± 15%, n = 4; P = 0·0286).

Figure 1.

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR detected in monocytes during dengue fever (DF). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy subjects or samples from dengue patients taken at the febrile phase or defervecence were analyzed using double-colour flow cytometry for (a) adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (CD54) (Controls, n = 10; Febrile, n = 15; Defervecence, n = 16) or (b) HLA-DR (Controls, n = 10; Febrile, n = 26; Defervecence, n = 24) expression on CD14+ cells. Box-and-whisker plot. The box extends from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile and the line at the middle is the median. The error bars, or whiskers, extend down to the lowest value and up to the highest. Statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test. *P < 0·05 and **P < 0·01.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry profile of monocytes during dengue fever. Representative contour plots from patients during the acute phase of the disease and in healthy subjects and respective control isotypes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were labelled as described in the Materials and methods and were analysed by flow cytometry within the monocyte gate. Ex vivo analysis of CD54, human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 expression on CD14+ cells. The numbers in quadrants indicate the percentage of cells corresponding to the cell subset. ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1.

Figure 3.

(a) Cellular flow cytometry profile showing size and granulosity of cells during dengue fever. (b) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were tri-labelled with specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) CD14, CD11c and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR and analysed by flow cytometry within the monocyte gate. (c) Representative histograms are shown of HLA-DR expression among CD14+ CD11c+ monocytes between groups of patients with mild dengue, severe dengue and healthy individuals. Cy, cycrome; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

TLR2 and TLR4 are expressed on the surface of monocytes from patients with DF

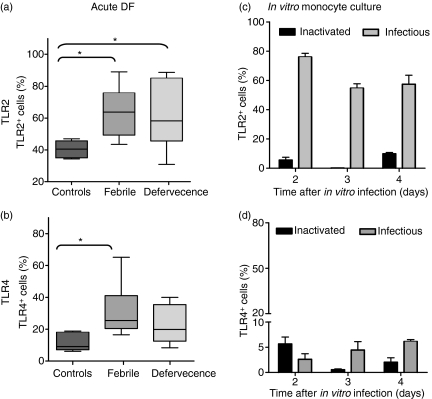

TLRs are expressed on monocytes, and under pathological conditions these molecules may be up-regulated and correlated with several inflammatory parameters, such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and cytokine expression.11 Interestingly, TLR2 and TLR4 were found to be expressed on the surface of monocytes isolated from dengue patients at the acute phase of the disease. Cell-surface labelling for TLR2 and TLR4, performed on PBMCs, showed that the mean percentage of TLR2+ monocytes was significantly higher in patients than in healthy PBMC donors (Figs 2c and 4a). The mean percentage of TLR4+ monocytes was significantly higher in patients at the febrile phase than in controls (Figs 2d and 4b). No significant difference was observed in relation to immune status (primary and secondary infection) or infecting virus serotype. The mean percentage of TLR8+ monocytes was higher in patients than in controls (controls 8 ± 1%, n = 4 versus dengue patients 12 ± 10%, n = 8). The mean percentage of TLR3+ monocytes was not changed in dengue patients compared with healthy individuals (data not shown). We tested 23 samples for the presence of LPS. None of these samples from patients showed a positive reaction in the LPS-detection assay.

Figure 4.

Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 detected on monocytes from patients with dengue fever (DF) or after in vitro infection. Box-and-whisker plots represent data from TLR2 and TLR4 expression. (a, b) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy subjects (n = 6) or samples from dengue patients taken on the fever day (n = 10) and during defervescence (n = 13). (c, d) Monocyte-enriched human PBMCs (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured for 2–4 days with DENV-2 (16681) or inactivated virus. Cultures were labelled with anti-TLR2 phycoerythrin (PE) or TLR-4 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugates, or their control antibodies. Statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test. *P < 0·05.

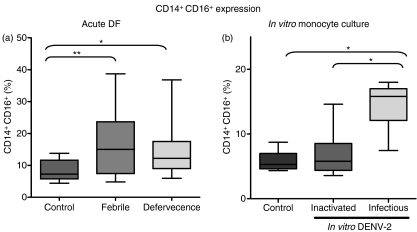

The numbers of CD16+ monocytes are increased in patients with DF

Three different cell subsets of human monocytes are defined by flow cytometry analysis, according to their CD14 and CD16 surface expression. Expression of the CD14+ CD16+ cell subset is increased after monocyte activation by factors such as LPS and this subset is known to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α.25 To investigate whether these subsets differ in surface antigen expression during DF, a two-colour analysis was performed and monocytes were divided into two subsets according to their CD14 and CD16 expression. CD14+ CD16+ monocytes constituted a markedly increased population in dengue patients when compared with healthy individuals. They were altered both in febrile and defervecent phases of dengue (Fig. 5a). The CD14+ CD16− monocyte subset was lower in dengue patients when compared with healthy individuals. No difference was found between febrile and defervescence phases of dengue.

Figure 5.

CD14+ CD16+ expression on monocytes during acute dengue fever (DF) and in vitro monocyte culture. Box-and-whisker plots represent data from (a) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy subjects (n = 14) or samples from dengue patients taken at the febrile phase (n = 25) or during defervecence (n = 25) and analyzed using double-colour flow cytometry for CD16 expression in CD14+ cells. Statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (b) Human monocytes were obtained from buffy coats and incubated with cell culture medium, or with heat-inactivated or infectious dengue virus 2 (DENV-2) (strain 16681). Box-and-whisker plots represent experiments performed with cells from seven different PBMC donors. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (anova) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

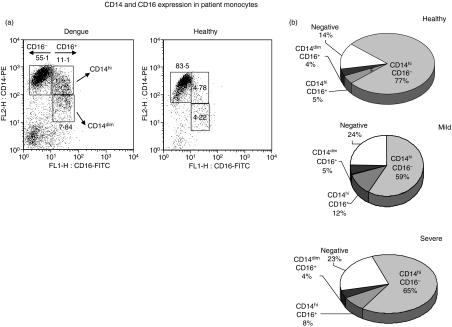

CD16+ monocytes may display CD14 at different intensities; we determined the rates for the two cell subsets – CD14high CD16+ and CD14low CD16+– within the monocyte gate and we found that they differed in frequency between the dengue patients and healthy individuals (Fig. 6a). In fact, the CD14high CD16+ cell subset was increased in patients with mild dengue when compared to patients with severe dengue or healthy subjects (Fig. 6b; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test with P < 0·05 and P < 0·001, respectively).

Figure 6.

Distribution of CD14 and CD16 on monocyte subsets in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from patients during acute dengue fever. Cells labelled with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against CD14 and CD16 can be separated into three distinct subsets: CD14high CD16−; CD14high CD16+; and CD14low CD16+. (a) Scatter plots from a representative patient with dengue fever (DF) and a healthy individual were analyzed by flow cytometry within the monocyte gate. (b) Monocyte subset distribution during dengue fever. There was a significantly higher level of CD14high CD16+ cells in patients with mild dengue (12 ± 7%, n = 30) than in patients with severe dengue (8 ± 3%, n = 23) or in healthy subjects (4·5 ± 1·2%, n = 14). One-way analysis of variance (anova) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test with P < 0·05 and P < 0·001, respectively.

Characterization of DENV target cells and infection rates

Monocytes, as dendritic cells, have been described as important target cells for DENV, both in vivo and in vitro.26,27 As a model for studying DENV interactions with host cells, we used freshly isolated PBMCs enriched by adherence for monocyte content and infected with DENV-2.23

CD16+ monocyte frequencies increase during in vitro infection

DENV antigen (Ag), detected intracellularly, peaked on day 2 and decreased subsequently (data not shown). We observed that both subsets – CD14+ CD16− and CD14+ CD16+– are positive for DENV-Ag (Fig. 7a). CD14high and CD14low could not be differentiated after in vitro infection because CD14 tends to decay in culture over time. During the in vitro infection of monocytes from healthy donors with DENV-2 we observed that the CD14+CD16+ cell subset was significantly increased 2 days after DENV-2 infection (Fig. 5b).

Figure 7.

Dengue virus targets in monocyte cultures. Monocyte-enriched human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (2 × 105 cells/well) were incubated for 2 days with dengue virus 2 (DENV-2) (strain 16681). (a) Representative contour plot for CD14+ CD16+ expression during in vitro dengue infection triple-labelled with anti-CD14-cycrome (Cy), CD16-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and anti-DENV-Alexa 647 or their control antibodies (monocyte-gated cells). Representative histograms showing typical DENV-antigen (Ag) positive cells were detected on CD14+ CD16− classical monocytes and on CD14+ CD16+ monocytes by flow cytometry. Inactivated virus showed no detectable labelling (data not shown). (b) Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and DENV-Ag expression in human monocytes. Monocytes, double labelled with anti-DENV-Alexa 647 and anti-TLR2-phycoerythrin (PE) (monocyte-gated cells), after 2 days (early) or 5 days (late) of infection with DENV-2 (16681). Quadrants were set by isotype-control antibodies.

TLR2 but not TLR4 is expressed on the monocyte surface after in vitro DENV-2 infection

TLR2 and TLR4 are basally expressed in very few monocytes in culture. During the second day of DENV-2 infection, gated monocytes were already highly positive for TLR2, but not for TLR4 (Fig. 4c,d) or TLR3 (data not shown). DENV-2 virus infects TLR2+ cells at low rates, as shown in Fig. 7b. Most monocytes that expressed TLR2 were already DENV-Ag negative on the second day after infection (68 ± 2·5%); only a few monocytes expressed both TLR2 and DENV-Ag (5·7 ± 0·5%) and some monocytes expressed only DENV-Ag without TLR2, suggesting that either the virus might induce soluble factors which may stimulate the TLR2 expression without intracellular infection or that the virus is destroyed before TLR2 is expressed. The same is valid for days 3 and 4. (Representative contour plots are shown for 2- and 5-day infection in Fig. 7b). TLR3 was not detected on CD14+ monocytes from human cell cultures infected with DENV-2 (cell culture medium, 0·6 ± 0·6%; heat-inactivated DENV, 0·8 ± 1·2%; and infectious DENV, 1·1 ± 1·0%).

Correlation between monocyte subsets and circulating cytokines

We carried out immunoassays to investigate the status of circulating IL-10, IL-18, IFN-γ and TNF-α in Brazilian patients with acute-phase dengue. These cytokines were present at significantly elevated levels in the plasma from most dengue patients. TNF-α became detectable during the febrile phase of illness compared with controls: 25 ± 39 versus 63 ± 115 pg/ml for TNF-α, increasing to 95 ± 280 pg/ml at the defervescence phase. The plasma levels of IL-10 increased with fever onset and reached peak levels by defervescent days (124 ± 164 and 137 ± 158 pg/ml, respectively). IL-18 became detectable during the febrile phase of illness (320 ± 215 pg/ml) and diminished (to 280 ± 121 pg/ml) during the defervescent phase. IFN-γ followed a different pattern, being 217 ± 423 pg/ml during fever and 418 ± 1169 pg/ml at defervescence (Fig. S1).

Interestingly, we observed a significant, negative correlation between CD14high CD16+ monocytes and the plasma levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL18 in samples from dengue patients (Spearman r correlation; P < 0·05, n = 22) (Fig. S2). In addition, CD14high CD16+ monocytes were positively associated with CD14+ CD54+ cells (P < 0·01, n = 26), and CD14low CD16+ monocytes showed a significant, negative correlation with CD14+ TLR4+ monocytes (P < 0·02, n = 20).

Association of DF severity with TLR2, TLR4 and HLA-DR expression on monocytes

In addition, we investigated whether cell activation and/or adhesion molecules on monocytes differ between patients with mild and severe DF in order to predict disease severity. The platelet counts shown in Table 1 were inversely proportional to the severity of dengue, as expected. Moreover, the expression of HLA-DR, and of TLR2 and TLR4, on CD14+ cells was observed to be higher in patients with mild dengue compared to patients with severe dengue (Table 1). No differences were found in the levels of ICAM-1 expressed by CD14+ cells between the two groups of patients with dengue. Monocyte activation leading to inflammatory reactions generates a benefit to the host after DENV infection, probably by triggering an effective virus control.

Table 1.

Association of dengue fever severity with platelet counts, toll-like receptor (TLR)2, TLR4 and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR expression on CD14+ monocytes

| Control (n = 10)1 | Mild (n = 20–26) | Severe (n = 7–24) | Mild versus Severe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets (× 103/mm3) | 271·0 ± 36 | 171 ± 822 | 53 ± 27 | ***3 |

| HLA-DR | ||||

| (%) | 91·7 ± 2·5 | 73·7 ± 3·3***5 | 72·7 ± 4·4*** | NS |

| (MFI)4 | 18 ± 6·3 | 25 ± 15 | 15 ± 6·2 | * |

| TLR2 | ||||

| (%) | 40 ± 4·1 | 67 ± 15***5 | 46·9 ± 4·5 | ** |

| (MFI) | 12 ± 2·3 | 25 ± 19·0** | 12·6 ± 9·0 | * |

| TLR4 | ||||

| (%) | 12 ± 5·0 | 30·3 ± 16** | 17·1 ± 6·9 | * |

| (MFI) | 6·5 ± 1·0 | 10·7 ± 4·1* | 6·7 ± 3·8 | * |

The number of subjects studied in each group is given in parentheses.

Data are expressed as average ± standard deviation.

P-values for the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare mild dengue fever versus severe dengue fever groups. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001. NS means not significant.

MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

P-values for the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare the results of different groups versus the controls. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

Discussion

The immunopathogical mechanisms contributing to the development of severe clinical manifestations during DF are not yet fully understood. As monocytes are primary targets for circulating viruses we aimed to elucidate their role in disease severity or protection, focusing on monocyte-activation patterns during in vitro infection with DENV-2 and in circulating cells from patients with DF. We have previously shown that monocytes infected in vitro with DENV-2 achieved intracellular antigen peak levels after 2 days in culture and that DENV could be detected in peripheral monocytes from patients. In addition, these cells were activated, as demonstrated by iNOS expression ex vivo and after in vitro infection of monocytes from healthy donors.23 Our present study showed that during DENV infection, monocytes acquire a non-classical profile by increased co-expression of CD14+ CD16+ and also by expression of TLR2.

Characteristically, CD14+ CD16+ are pro-inflammatory monocytes that have an increased capacity to produce cytokines such as TNF-α. In fact, the CD14+ CD16+ subset, in contrast to CD14+ non-expressing CD16 classical monocytes, represent < 10% of the total monocytes in normal blood but are increased in a variety of various inflammatory diseases.8,28 We observed that patients with mild dengue have an increased number of CD14high CD16+ monocytes in the peripheral blood. Other monocyte subsets have been described in the literature. In this context, the CD14low CD16+ subset is considered as pro-inflammatory because it can produce, upon stimulation with LPS, more TNF-α than CD14high CD16− classical monocytes and little IL-10. By contrast, the CD14high CD16+ subset has higher CD14 expression and has already been well characterized during other pathologies.25 A recent report also demonstrated that this cell subset exhibited an increased phagocytic activity and produced little TNF-α, significantly more IL-10 than CD14low CD16+ monocytes and higher expression of TLR4.10 In our hands, a significant, negative correlation between CD14high CD16+ monocytes and TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-18 plasma levels in dengue patients (Spearman r correlation; P < 0·05, n = 22) is in agreement with the evidence that these cytokines are associated with the severity of dengue disease.19,24,29 In addition, CD14low CD16+ monocytes showed a significant, negative correlation with CD14+ TLR4+ monocytes (P < 0·02, n = 20).

Considering the increased IL-10 plasma levels in DENV patients, we can speculate that CD14high CD16+ monocytes, found here to be associated with mild dengue, may produce IL-10 and drive the IL-10 production by T-regulatory cells, which can prevent immunopathology in several other infections and are also able to suppress the production of vasoactive cytokines after dengue-specific stimulation. Indeed, T-regulatory cell frequencies are increased in mild cases of dengue,30 and IL-10 production by regulatory T cells has been implicated in maintaining the balance between pathogen elimination and immunopathology during viral infections.31 Moreover, IL-10 has emerged as a key immunoregulatory molecule during infection with viruses, decreasing the excessive T-helper 1 and CD8 T-cell responses, resulting in IFN-γ and TNF-α overproduction, which ultimately may be responsible for immunopathology observed during viral infections.32

Antigen presentation by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), as monocytes and dendritic cells, involves the uptake of foreign antigen that is processed and presented in the context of MHC class II molecules. CD14+ CD16+ non-classical monocytes show higher HLA-DR expression than CD14+ non-expressing CD16 classical monocytes, predicting a higher antigen-presenting activity in these cells.33 In the group of patients with severe DF, despite the higher CD14+ CD16+ frequency, we found a lower percentage of monocytes expressing HLA-DR. Similarly, decreased HLA-DR expression on monocytes is also found in patients with sepsis and acute liver failure34,35 or during human herpesvirus-636 and hepatitis C virus37 infections.

Despite the fact that the numbers of non-classical CD14+ CD16+ monocytes were increased during the acute phase of the disease and in monocytes infected in culture with DENV-2, suggesting a role for CD14+ CD16+ during dengue infection, we observed that both monocyte subsets – CD14+ CD16+ and CD14+ CD16−– were infected with DENV. The numbers of classical CD14+ CD16− monocytes were decreased during the acute phase, and this phenomenon may be caused by the fact that DENV replication results in the apoptosis of these cells, suggesting that antigen may be infecting these cells preferentially. In fact, we have observed that CD14+ monocytes infected with DENV-2 expressed higher levels of death receptor Fas (CD95) and possibly may be susceptible to apoptotic processes (Torrentes-Carvalho et al., 2009).38 Also, pre-apoptotic dendritic cells (characterized by a low membrane potential) showed a modified phenotype, with down-regulation of HLA-DR and of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86.39 Accordingly, we observed that monocytes showed lower levels of expression of HLA-DR in patients with severe dengue. Finally, the altered expressions of CD14+ CD16+ and HLA-DR on monocytes suggest their role in the pro-inflammatory reaction during DF.

We have demonstrated that adhesion molecules such as very late antigen-4 (VLA-4), ICAM-1 and lymphocyte function activation-1 (LFA-1) are frequently found on activated CD8 T cells and also on CD4 T cells during the acute phase of DF.24 In the present study, we showed that CD14+ monocytes from dengue patients also expressed higher ICAM-1 levels than CD14+ monocytes from healthy individuals. In fact, there is an ICAM-1 engagement with the human major group rhinovirus that enhances adhesiveness and homotypic aggregation of human monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells.40 Therefore, we believe that activated CD14+ monocytes expressing adhesion molecules are recruited to inflammatory sites and contribute to the inducement of inflammatory events found frequently in DF. Moreover, DENV antigens were detected in many tissues obtained from patients with DHF/DSS41 and might play a role in providing a chemotactic stimulus to attract activated cells. These results support the evidence of cell activation and are in agreement with the higher levels of soluble ICAM-1 in plasma, observed in dengue patients.24

The CD14+ CD16+ monocytes demonstrate features of differentiated monocytes or tissue macrophages, such as those migrating into tissues.25 It has been demonstrated that increased levels of CD14+ CD16+ monocytes are present in the peripheral blood of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)42 and are associated with acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) dementia.43 Also, increased CD16 expression on macrophages during rheumatoid arthritis is correlated with higher circulating TNF-α levels.25 Another cytokine, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is one of many cytokines increased in the plasma of dengue patients24 and it was shown to induce CD16 on blood monocytes in another report.44

The implication of TLRs in viral infections has been studied,45 but the knowledge in dengue is limited. Kruif et al.46 evaluated TLR gene-expression profiling of children with severe dengue infections. The authors demonstrated that TLR4 receptor 3 and TLR7 gene transcription were up-regulating, while TLR4 receptor 4, TLR1 and TLR2 were down-regulating, indicating the in vivo role of particular TLRs with different disease-severity parameters. Recently, Tsai et al. used different clones of an HEK293 (human embryonic kidney cell line) cell line transfected with different TLR molecules. The authors demonstrated that after DENV-2 infection, HEK293 transfected with TLRs 3, 7 and 8 induced IL-8 secretion. The higher IL-8 production and also IFN type I was observed after TLR3 activation.47 In addition, it has also been described that some viruses can develop a mechanism of evasion of the innate response against virus infection. In this context, Chen et al.48 demonstrated that in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection there was a reduced expression of TLR2 in PBMCs associated with more severe virus genotype C. Another virus, human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) down-regulates the host immune response by inhibiting TLR9 transcription, decreasing the related pathways and establishing a persistent infection.49 A recent report also demonstrated that herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) engage TLR2 on the dendritic cell surface and induce IL-6 and IL-12 secretion.50

This investigation is the first clinical study to determine the expression of TLR on peripheral blood monocytes from patients with DF and during in vitro infection. The expression of both TLR2 and TLR4 is significantly increased on monocytes during the acute phase of the disease (Fig. 4a,b). TLR4 is well known as the receptor for LPS, a product of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.51,52 We have eliminated the possible influence of contaminating LPS for activating TLRs on the cells of patients with DENV because the samples studied for TLRs expression were essentially free of endotoxin, as determined using the Limulus amebocyte assay, and these patients had leucopenia, which is usually present during viral infections.

The LPS binding to TLR4 triggers human monocytes to produce cytokines, which play a dominant role in the inflammatory response, as can be observed during sepsis and after polytrauma.52 However, in addition to LPS, cytokines also may have the potency to regulate the immune response through TLR4. TLR4 down-regulation by TNF-α was associated with LPS hyporeactivity for NF-κB formation, whereas TLR4 up-regulation by IL-6 was able to increase the responsiveness of mononuclear phagocytes.53 Iwahashi et al. reported a high frequency of circulating CD16+ TLR2+ monocytes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with healthy individuals. In the same work, it was observed that cytokines, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and IL-10, were crucial in TLR2 induction during CD16 monocyte and macrophage maturation. After stimulation with anti-FCyRIII antibody and TLR2 agonist, TNF-α production was increased.54 Finally, these observations suggest that the expression of TLR2 and TLR4 can be regulated at sites of infection or inflammation, either directly by bacterial components or indirectly by cytokines.53,55 Interestingly, only patients with mild DF showed a marked increase in TLR2/4 and the alterations were not observed in patients with severe DF.

Recent data have shown that TLRs have the ability to recognize more than one ligand and that TLR4 and TLR2 are the best examples of this high promiscuity.51,56–58 TLR2 recognizes a wide range of ligands, including lipoteichoic acids, lipoproteins and glycoproteins, zymosan and peptidoglycan, as well as LPS from specific bacterial strains.59

The results presented here indicate that DENV infection can alter the innate immune response. The TLR functions as receptors during dengue infection are not yet clear, but these receptors may regulate multiple cytokine pathways such as NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3). In addition, TLRs, found to be regulated on monocytes during dengue disease, can hypothetically be triggered by viral proteins such as NS1 or other endogenous molecules. The consequences of TLR activation are mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), NF-κB and IRF-3 activation, leading to the production of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12 and IFN-α, which, in turn, regulate the innate and adaptative immune responses.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that monocytes became activated during in vitro and in vivo infection with DENV and this activation pattern may influence the disease outcome. These changes consist of the up-regulation of molecules such as ICAM, CD16 and TLRs, and the down-regulation of HLA-DR. During TLR up-regulation, inflammatory cytokine production may remain controlled, but during severe DF this response becomes unbalanced, HLA-DR molecules are down-regulated, the antiviral response is less intense than the cytokine inflammatory response, and vascular leakage and coagulation disorders may be prevalent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (IOC) and Vice-Presidência de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Tecnológico (PDTSP-Dengue & PDTIS-Plataformas Tecnológicas, VPPDT), at FIOCRUZ; DECICT/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and ICGEB (International Centre for Genetic Engineering).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Ag

antigen

- AIDS

acquired immune-deficiency syndrome

- anova

analysis of variance

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- Cy

cycrome

- DENV

dengue virus

- DF

dengue fever

- DHF/DSS

dengue haemorrhagic fever or shock syndrome

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HLA

human leucocyte antigen

- HPV16

human papillomavirus type 16

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- IRF-3

interferon regulatory factor 3

- LFA-1

lymphocyte function activation-1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappaB

- NO

nitric oxide

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PE

phycoerythrin

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- TCID50

50% tissue culture infectious dose

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-β1

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- VCAM

vascular cell adhesion molecule

- VLA-4

very late antigen 4

- WHO

World Health Organization

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. (a) Plasma levels of cytokines TNF-α, IL-18, IL-10 and IFN-γ were quantified in dengue patients at febrile phase and defervecence. Significant increase in: (a) IL-18 levels in dengue patients are increase on febrile phase (320 ± 215 pg/ml) and diminished to 280 ± 121 pg/ml at defervescent phase. (b) IL-10 plasma levels increased at febrile phase, and reached peak levels at defervecence (124 ± 164 and 117 ± 158 pg/ml, respectively). (c) TNF-α became detectable during febrile phase of illness 963 ± 115 pg/ml) and (95 ± 280 pg/ml) at the defervescence phase. (d) IFN- γ plasma levels increased at febrile phase, and reached peak levels at defervecence (217 ± 423 pg/ml during fever and 418 ± 1169 pg/ml at defervescence).

Figure S2. Spearman correlation (r and P-values) was calculated to determine relationships between cytokine levels and CD14high CD16+ monocytes.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Nogueira RMR, de Araújo JMG, Schatzmayr HG. Dengue viruses in Brazil, 1986–2006. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/Pan. Am J Public Health. 2007;22:358–63. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892007001000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazilian-Health-Ministry Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim epidemiológico, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Informe Epidemiológico da Dengue. Janeiro a Novembro de 2008. 2009. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/boletim_dengue_janeiro_novembro.pdf [accessed on 26 December 2009]

- 3.Gibbons RV, Vaughn DW. Dengue: an escalating problem. BMJ. 2002;324:1563–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avila-Aguero ML, Avila-Aguero CR, Um SL, Soriano-Fallas A, Canas-Coto A, Yan SB. Systemic host inflammatory and coagulation response in the dengue virus primo-infection. Cytokine. 2004;27:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clyde K, Kyle JL, Harris E. Recent advances in deciphering viral and host determinants of dengue virus replication and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2006;80:11418–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01257-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chareonsirisuthigul T, Kalayanarooj S, Ubol S. Dengue virus (DENV) antibody-dependent enhancement of infection upregulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, but suppresses anti-DENV free radical and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, in THP-1 cells. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:365–75. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leong AS, Wong KT, Leong TY, Tan PH, Wannakrairot P. The pathology of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:227–36. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Fingerle G, Strobel M, Schraut W, Stelter F, Schutt C, Passlick B, Pforte A. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibits features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2053–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grage-Griebenow E, Flad HD, Ernst M. Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skrzeczynska-Moncznik J, Bzowska M, Loseke S, Grage-Griebenow E, Zembala M, Pryjma J. Peripheral blood CD14highCD16+ monocytes are main producers of IL-10. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:152–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–45. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowie AG, Haga IR. The role of Toll-like receptors in the host response to viruses. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:859–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:924–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phuong CX, Nhan NT, Kneen R, et al. Clinical diagnosis and assessment of severity of confirmed dengue infections in Vietnamese children: is the world health organization classification system helpful? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:172–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris E, Videa E, Perez L, et al. Clinical, epidemiologic, and virologic features of dengue in the 1998 epidemic in Nicaragua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;2:5–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.W.H.O. Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response (CSR) disease outbreaks reported 8 May Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever in Brazil – Update 2. 2002. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2002_05_08/en/index.html [accessed on 27 December 2009]

- 17.Balmaseda A, Hammond SN, Perez MA, Cuadra R, Solano S, Rocha J, Idiaquez W, Harris E. Assessment of the World Health Organization scheme for classification of dengue severity in Nicaragua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:1059–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez Torres E. Dengue. Estudos Avançados. 2008;22:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozza FA, Cruz OG, Zagne SM, Azeredo EL, Nogueira RM, Assis EF, Bozza PT, Kubelka CF. Multiplex cytokine profile from dengue patients: MIP-1beta and IFN-gamma as predictive factors for severity. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogueira RM, Miagostovich MP, Cavalcanti SM, Marzochi KB, Schatzmayr HG. Levels of IgM antibodies against dengue virus in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Res Virol. 1992;143:423–7. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(06)80136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nogueira RM, Miagostovich MP, Schatzmayr HG. Molecular epidemiology of dengue viruses in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2000;16:205–11. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miagostovich MP, Nogueira RM, dos Santos FB, Schatzmayr HG, Araujo ES, Vorndam V. Evaluation of an IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for dengue diagnosis. J Clin Virol. 1999;14:183–9. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neves-Souza PC, Azeredo EL, Zagne SM, Valls-de-Souza R, Reis SR, Cerqueira DI, Nogueira RM, Kubelka CF. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in monocytes during acute Dengue Fever in patients and during in vitro infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azeredo EL, Zagne SM, Alvarenga AR, Nogueira RM, Kubelka CF, de Oliveira-Pinto LM. Activated peripheral lymphocytes with increased expression of cell adhesion molecules and cytotoxic markers are associated with dengue fever disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:437–49. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:584–92. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halstead SB, Porterfield JS, O’Rourke EJ. Enhancement of dengue virus infection in monocytes by flavivirus antisera. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:638–42. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu SJ, Grouard-Vogel G, Sun W, et al. Human skin Langerhans cells are targets of dengue virus infection. Nat Med. 2000;6:816–20. doi: 10.1038/77553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braga EL, Moura P, Pinto LM, Ignacio SR, Oliveira MJ, Cordeiro MT, Kubelka CF. Detection of circulant tumor necrosis factor-alpha, soluble tumor necrosis factor p75 and interferon-gamma in Brazilian patients with dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:229–32. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luhn K, Simmons CP, Moran E, et al. Increased frequencies of CD4+ CD25(high) regulatory T cells in acute dengue infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:979–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suvas S, Azkur AK, Kim BS, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control the severity of viral immunoinflammatory lesions. J Immunol. 2004;172:4123–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosser DM, Zhang X. Interleukin-10: new perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:205–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon S. Pathogen recognition or homeostasis? APC receptor functions in innate immunity. C R Biol. 2004;327:603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antoniades CG, Berry PA, Davies ET, Hussain M, Bernal W, Vergani D, Wendon J. Reduced monocyte HLA-DR expression: a novel biomarker of disease severity and outcome in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2006;44:34–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, Volk HD, Kox W. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–81. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janelle ME, Flamand L. Phenotypic alterations and survival of monocytes following infection by human herpesvirus-6. Arch Virol. 2006;151:1603–14. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0715-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Averill L, Lee WM, Karandikar NJ. Differential dysfunction in dendritic cell subsets during chronic HCV infection. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torrentes-Carvalho A, Azeredo EL, Reis SRI, Miranda AS, Gandini M, Barbosa LS, Kubelka CF. Dengue virus-2 infection and the induction of apoptosis in human primary monocytes. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:1091–9. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000800005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castera L, Hatzfeld-Charbonnier AS, Ballot C, et al. Apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction defines human monocyte-derived dendritic cells with impaired immuno-stimulatory capacities. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1321–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchberger S, Vetr H, Majdic O, Stockinger H, Stockl J. Engagement of ICAM-1 by major group rhinoviruses activates the LFA-1/ICAM-3 cell adhesion pathway in mononuclear phagocytes. Immunobiology. 2006;8:537–47. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jessie K, Fong MY, Devi S, Lam SK, Wong KT. Localization of dengue virus in naturally infected human tissues, by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1411–8. doi: 10.1086/383043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ancuta P, Kunstman KJ, Autissier P, Zaman T, Stone D, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D. CD16+ monocytes exposed to HIV promote highly efficient viral replication upon differentiation into macrophages and interaction with T cells. Virology. 2006;344:267–76. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Sverstiuk AE, et al. CNS invasion by CD14+/CD16+ peripheral blood-derived monocytes in HIV dementia: perivascular accumulation and reservoir of HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:528–41. doi: 10.1080/135502801753248114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wahl SM, Allen JB, Welch GR, Wong HL. Transforming growth factor-beta in synovial fluids modulates Fc gamma RII (CD16) expression on mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol. 1992;148:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang SY, Jouanguy E, Sancho-Shimizu V, et al. Human Toll-like receptor-dependent induction of interferons in protective immunity to viruses. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:225–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Kruif MD, Setiati TE, Mairuhu AT, et al. Differential gene expression changes in children with severe dengue virus infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai YT, Chang SY, Lee CN, Kao CL. Human TLR3 recognizes dengue virus and modulates viral replication in vitro. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:604–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z, Cheng Y, Xu Y, et al. Expression profiles and function of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronic hepatitis B patients. Clin Immunol. 2008;128:400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasan UA, Bates E, Takeshita F, et al. TLR9 expression and function is abolished by the cervical cancer-associated human papillomavirus type 16. J Immunol. 2007;178:3186–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sato A, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Dual recognition of herpes simplex viruses by TLR2 and TLR9 in dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17343–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605102103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Essakalli M, Atouf O, Bennani N, Benseffaj N, Ouadghiri S, Brick C. [Toll-like receptors.] Pathol Biol (Paris) 2009;57:430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamandl D, Bahrami M, Wessner B, et al. Modulation of toll-like receptor 4 expression on human monocytes by tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6: tumor necrosis factor evokes lipopolysaccharide hyporesponsiveness, whereas interleukin-6 enhances lipopolysaccharide activity. Shock. 2003;20:224–9. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwahashi M, Yamamura M, Aita T, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptor 2 on CD16+ blood monocytes and synovial tissue macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1457–67. doi: 10.1002/art.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muzio M, Bosisio D, Polentarutti N, et al. Differential expression and regulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) in human leukocytes: selective expression of TLR3 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:5998–6004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Georgel P, Jiang Z, Kunz S, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G activates a specific antiviral Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Virology. 2007;362:304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jude BA, Pobezinskaya Y, Bishop J, Parke S, Medzhitov RM, Chervonsky AV, Golovkina TV. Subversion of the innate immune system by a retrovirus. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:573–8. doi: 10.1038/ni926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beutler B. Neo-ligands for innate immune receptors and the etiology of sterile inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:113–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.