Abstract

Cells use redox signaling to adapt to oxidative stress. For instance, certain transcription factors exist in a latent state that may be disrupted by oxidative modifications that activate their transcription potential. We hypothesized that DNA-binding sites (response elements) for redox-sensitive transcription factors may also exist in a latent state, maintained by co-repressor complexes containing class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes, and that HDAC inactivation by oxidative stress may antagonize deacetylase activity and unmask electrophile-response elements, thus activating transcription. Electrophiles suitable to test this hypothesis include reactive carbonyl species, often derived from peroxidation of arachidonic acid. We report that α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, e.g. the cyclopentenone prostaglandin, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2), and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4HNE), alkylate (carbonylate), a subset of class I HDACs including HDAC1, -2, and -3, but not HDAC8. Covalent modification at two conserved cysteine residues, corresponding to Cys261 and Cys273 in HDAC1, coincided with attenuation of histone deacetylase activity, changes in histone H3 and H4 acetylation patterns, derepression of a LEF1·β-catenin model system, and transcription of HDAC-repressed genes, e.g. heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), Gadd45, and HSP70. Identification of particular class I HDACs as components of the redox/electrophile-responsive proteome offers a basis for understanding how cells stratify their responses to varying degrees of pathophysiological oxidative stress associated with inflammation, cancer, and metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Corepressor Transcription, Histone Deacetylase, Histone Modification, Oxidative Stress, Thiol, 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal, Euchromatin, Heterochromatin, Redox, Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins

Introduction

Cellular oxidative stress can vary widely in severity and scope. Consequently, redox signaling must accommodate physiological demands from respiration, metabolism, host defense, cell replication, and aging plus demands from pathological oxidative stress encountered during inflammation, malignancy, reperfusion injury, and metabolic syndrome. Stimulus-response coupling in these different situations must be properly stratified; otherwise, maladaptation can have grave outcomes. An insufficient response to oxidative stress can lead to cell death, which typifies many neurodegenerative diseases. An excessive response to oxidative stress can lead to hypertrophy, hyperplasia, or neoplasia (1).

Phenotypic adaptation to oxidative stress derives, in part, from the expression of genes to protect cells from damage, to repair damage, and to bolster their survival. This involves cellular proteins collectively termed the redox/electrophile-responsive proteome (2, 3). These proteins vary widely in cellular localization and functionality, but all have cysteine residues with distinctively nucleophilic thiols (pKa ≤ 5), which are readily oxidized to sulfenic/sulfinic acids by reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 or readily alkylated by reactive carbonyl species (RCS) (4, 5). RCS originate from either non-enzymatic or enzymatic peroxidation of lipids (especially arachidonic acid), which generates α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (enals) (e.g. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4HNE), crotonaldehyde, acrolein) and α,β-unsaturated ketones (enone) (e.g. cyclopentenone prostaglandins). Post-translational covalent modification of cysteinyl thiols by RCS has been termed “carbonylation” (6), and carbonylation of proteins is a distinctive feature of cellular redox signaling by peroxiredoxins (7, 8), tyrosine phosphatases (9, 10), and kinases (11, 12) and transcription factors (p53, NFκB, Nrf2).

Overall, we have a rudimentary understanding of how ROS and RCS integrate the actions of membrane and cytosolic proteins to govern redox-responsive transcription. By contrast, we know very little about the actions of RCS on nuclear proteins and processes beyond the investigations of Narumiya et al. (13–15), who first reported that cyclopentenone prostaglandins concentrated within the nucleus of cells via irreversible binding to unidentified nuclear and chromatin-associated proteins. The findings by Narumiya et al. (13–15) and the biological importance of proper stimulus-response coupling in cells exposed to oxidative stress prompted our hypothesis that regulation of redox-responsive transcription factors might coincide with redox regulation of proteins that alter chromatin dynamics. Prominent among these are histone deacetylases, which limit access to response elements on DNA within heterochromatin, thereby repressing gene expression. Mammalian class I HDAC1, -2, -3, and -8 are homologous to yeast RPD3 (16), reside in the nucleus, and may be incorporated into multiprotein gene repression complexes and co-repressor complexes such as mSin3a (17, 18), NuRD (19), and N-CoR/SMRT (20, 21). Repression and derepression of the lymphoid enhancer factor/T-cell factor (LEF/TCF) family of transcriptional activators/inhibitors by the recruitment of class I histone deacetylases (HDACs) typify this process (22, 23).

We report that RCS covalently modified a subset of class I HDACs including HDAC1, -2, and -3 as well as the yeast homologue RPD3, but not HDAC8. Covalent modification of two conserved cysteines, Cys261 and Cys273 in HDAC1, occurred in a dose- and time-dependent manner that led to attenuation of histone deacetylase, changes in histone H3 and H4 acetylation patterns, derepression of LEF1·β-catenin transactivation, and activation of RCS-sensitive genes repressed by HDACs. Our results imply that HDAC1, -2, and -3 isoenzymes are components of a redox/electrophile-responsive proteome that governs redox signaling in eukaryotes. Our data also suggest a mechanism by which cells might stratify their responses and adapt to varying intensities of oxidative stress and may explain, in part, how maladaptation can influence the etiology of cancer, atherosclerosis, or other chronic diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Cyclopentenone prostaglandins including biotinylated derivatives, 4HNE, and HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). NeutrAvidin agarose resin was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Primary antibodies for HDAC1 (H3284), HDAC2 (H3159), HDAC8 (H8038), and FLAG-M2 (F3165) as well as the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate were all from Sigma. Anti-HDAC3 (ab47237) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-acetyl-histone H3K14 (06-911), anti-Myc tag (05-724), and anti-acetyl-histone H4 (06-598) were all from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-acetyl-histone H3K9 (9671) was from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagents were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen. Mammalian cell lysis buffer for biotin capture by NeutrAvidin pulldown as well as for histone acetylation assays contained 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.1 m NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaF, and 1× CompleteTM protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) and 1% Triton X-100. Yeast lysis buffer contains 12% glycerol, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1× CompleteTM protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science). Reporter lysis buffer and luciferase assay system were from Promega (Madison, WI). Protein concentration from cell lysates was measured via Bradford analysis using the Bio-Rad protein assay solution (500-0006).

Cell Lines and Culture

All mammalian cell lines were propagated in medium containing penicillin and streptomycin and 2 mm l-glutamine. SuperTOPflash® (STF) and STF3a (HEK293) cell lines were maintained in advanced Dulbecco's minimum essential medium and 2% FCS (HyClone); A549 cells were grown in F-12 medium with 10% FCS; HL-60 cells were grown in RPMI with 10% FCS; and HCT116 cells were grown in McCoy's 5A medium with 10% FCS. Yeast cells were a gift from Dr. David Stillman, University of Utah (strain DY6092), grown in YP medium containing 2% glucose and at 30 °C.

Immunochemical Analysis (Western Blots) and NeutrAvidin Pulldown of Biotinylated HDACs

Adherent mammalian cell lines were grown to ∼90% confluency in 35-mm plates containing 1–2% serum. Cells were treated with biotinylated prostaglandins for the times and concentrations indicated. Following treatment, cells were washed twice with PBS, pH 7.4, at 4 °C and harvested in 140 μl of lysis buffer. Cells are completely lysed with one freeze/thaw cycle, and cellular debris was pelleted at 10,000 × g. Between 100 and 200 μg of total protein was incubated overnight at 4 °C in 1 ml of total volume of PBS, pH 7.4, with 0.4% Tween 20 and 40 μl of NeutrAvidin bead slurry to sequester biotinylated (protein·prostaglandin-biotin) proteins. Following incubation, beads were pelleted and washed four times with PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.4% Tween 20. Proteins were released from beads by boiling in 25 μl of 1.5× Laemmli buffer containing 3.75% β-mercaptoethanol for 5 min and assayed by Western immunoblot for individual HDACs. Histone acetylation was analyzed by Western blotting of 10 μg of total protein from whole cell lysates, separated on 10–20% SDS-PAGE gels.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells harboring stably inserted RPD3-Myc (strain DY6092) were treated with 15d-PGJ2-B at A600 of ∼0.30–0.35 in 10 ml of medium at 30 °C for the time indicated. Yeast were pelleted and lysed using 0.7-mm zirconia beads (Biospec Products, Inc.) in lysis buffer. RPD3-Myc·15d-PGJ2-B conjugates were precipitated from lysates with NeutrAvidin beads as above and assayed by immunoblot for Myc tag. Total histone H4 acetylation was assayed by separating 15 μg of total protein from whole cell lysates on 10–20% SDS-PAGE gels followed by immunoblotting.

Cloning and Site-directed Mutagenesis

MAD·LEF and MAD(Pro)·LEF chimeras, from Dr. Don Ayer, University of Utah School of Medicine, were prepared by cloning the first 105 bp of MAD upstream and in frame of full-length LEF1 (isoform 1) using EcoRI in expression vector pcDNA3.1. The MAD(Pro)·LEF mutant was prepared by mutating t35c (Leu12 to Pro12) and g46c (Ala16 to Pro16). We generated the Cys to Ser mutants of HDAC1-FLAG (from Eric Verdin, University of California San Francisco) via site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the following forward primers and their reverse complement primers: C261S, 5′-CGGTGGTCTTACAGAGTGGCTCAGACTCC-3′; C273S, 5′-TATCTGGGGATCGGTTAGGTAGCTTCAATCTAACTATC-3′.

HDAC Activity Assays

We prepared 3H-acetylated histone substrate from RKO cells as described previously (24). Radio-labeled histones (∼500 dpm/μg) were purified by acid extraction and dialysis (25) and lyophilized before use. Inhibition of HDAC activity was measured by treating recombinant HDAC3·N-CoR1 (5 ng/μl) in 60 μl of reaction buffer (50 mm Tris/Cl, pH 8.0, 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.25 mg/ml BSA) with vehicle, HDAC inhibitors TSA, sodium butyrate, or 15d-PGJ2-B and 4HNE for 15 min followed by the addition of 3H-acetylated histone substrate (15,000 dpm/reaction dissolved in distilled H2O) and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. The reaction was quenched with 10 μl of 10 n HCl/2.5 n acetic acid at 4 °C. Samples were extracted with 600 μl of ethyl acetate by vortexing for 10 s and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Released [3H]acetate was counted by adding 500 μl of the organic fraction to scintillation fluid. HDAC activity is measured as (counts (from test sample) (dpm) − counts (from vehicle control)(dpm))/((time (h)/volume of sample (ml)).

WNT/β-Catenin Signaling in STF and STF3a Cells

STF cells grown to ∼60–70% confluency in 35-mm wells were treated with vehicle or 15d-PGJ2 (0–30 μm) in 2% FCS for 18 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS, pH 7.4, at 4 °C and lysed in 200 μl of reporter lysis buffer. Cell debris was pelleted at 10,000 × g, and 20 μg of total protein was used in a luciferase assay system (Promega). Vehicle signal was normalized to a value of 1 luciferase count per second.

STF3a cells (Dr. David Virshup, Duke NUS Graduate Medical School) were used as described (26). STF3a cells (6 × 105 cells/well) were plated in 35-mm wells and grown overnight in antibiotic-free Dulbecco's minimum essential medium. MAD·LEF and MAD(Pro)·LEF chimeras were transfected (2 μg of DNA and 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000) according to manufacturer's directions. After 24 h of incubation, cells were treated with vehicle, TSA (100 nm), butyrate (150 μm), 15d-PGJ2 (10 μm), Δ12-PGJ2 (10 μm), or 4HNE (10 μm) for 18 h. Cells were washed twice in PBS, pH 7.4, and lysed in 125 μl of reporter lysis buffer. Cell debris was pelleted at 10,000 × g, and 20 μg of total protein was used to measure luciferase activity (i.e. expression). Results, mean ± S.E. (n = 3–4) were normalized to a value of 100% in cells transfected with MAD(Pro)·LEF.

15d-PGJ2-sensitive Gene Expression by Reverse Transcription-Quantitative PCR

A549 cells were grown to ∼70% confluency in 35-mm wells in antibiotic-free F-12 medium. HDAC1WT and HDAC1C261S/C273S plasmids were transfected (4 μg of DNA and 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000), and medium was changed to 10% FCS after 6 h according to the manufacturer's directions. After 24 h, medium was changed to 1% FCS, and cells were treated with either vehicle or 15d-PGJ2 (10 μm). After 1 h, FCS was added to the cells to 10%, and the cells were incubated for 23 h before harvesting. Total RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's directions followed by on-column DNase digestion. Total RNA was measured using a nanodrop spectrophotometer, and 2.5 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas) with oligo(dT)18 primers. The cDNA (1 μl) was used directly for quantitative PCR using SYBR Green master mix (Roche Applied Science) and the following primer pairs: HO-1, 5′-GTCTTCGCCCCTGTCTACTTC-3′, 5′-CTGGGCAATCTTTTTGAGCAC-3′; Gadd45, 5′-GAGAGCAGAAGACCGAAAGGA-3′, 5′-CACAACACCACGTTATCGGG-3′; HSP70, 5′-GCATCGAGACTATCGCTAATGAG-3′, 5′-TGCAAGGTTAGATTTTTCTGCCT-3′; GAPDH, 5′-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3′, 5′-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA-3′; β-actin, 5′-TTCCTGGGCATGGAGTC-3′, 5′-CAGGTCTTTGCGGATGTC-3′.

RESULTS

Cyclopentenone Prostaglandins Covalently Alkylate (Carbonylate) Class I HDAC1, -2, and -3 and Yeast RPD3

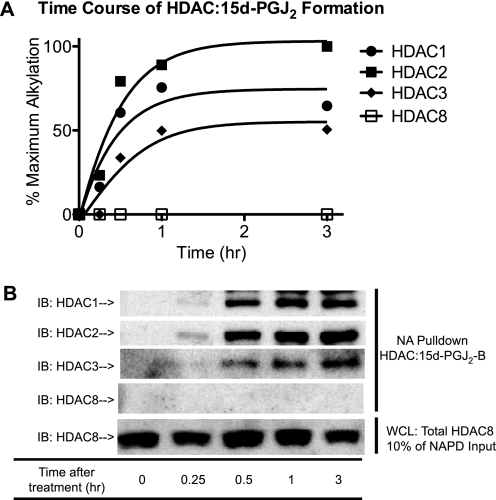

To investigate how RCS influence gene regulation via interaction with chromatin-associated proteins, we first tested whether HDACs are alkylated by cyclopentenone prostaglandins. PGD2 dehydrates spontaneously to form J-series enone and dienone prostaglandins (27) (supplemental Fig. 1D), which can react with nucleophilic cysteinyl thiolates (28) found in transcription factors, e.g. NFκB (29), KEAP·NRF2 (3), as well as unidentified chromatin-associated proteins (13). Hypothetically, any HDAC enzymes with redox-sensitive cysteinyl thiols should be prone to alkylation (carbonylation) by enones and enals. To test this hypothesis, we treated HEK293 cells with biotin analogs of 15d-PGJ2-B. The biotin epitope in PGJ congeners facilitates the isolation and identification of any cellular proteins they might alkylate (3, 11, 30). Immunoblot analysis showed that 5 μm 15d-PGJ2-B alkylated (carbonylated) cellular HDAC1, -2, and -3, but not -8. Formation of an HDAC·15d-PGJ2-B covalent adduct was detectable within 15 min; half-maximal by 30 min; and durable for longer than 180 min (Fig. 1, A and B, and data not shown). Alkylation of intracellular HDACs appears to prefer HDAC2 > HDAC1 > HDAC3; however, alkylation of HDAC8 was not detectable up to 6 h. We also tested the capability of PGD2-biotin, the precursor of 15d-PGJ2-B, in labeling cellular HDAC1. Similar to 15d-PGJ2-B, PGD2-biotin also accumulated HDAC1·PG-biotin adducts (supplemental Fig. 2), but ∼4-fold more slowly (supplemental Fig. 2). This kinetic difference derives from rate-limiting processes, such as dehydration of PGD2-biotin, which yields 15d-PGJ2-B as a terminal metabolite, and temperature-dependent transport of PGJ metabolites into the nucleus (14). PGD2, a prominent eicosanoid from mast cells (31) and other hematopoietic cells, helps resolve acute inflammation via mechanisms that involve its transformation into PGJ2, Δ12-PGJ2, and 15d-PGJ2 (32). Further investigations suggest that: 1) HDACs react with 15d-PGJ2-B (a bifunctional dienone) better than PGA1-biotin (a mono-functional enone), consistent with precedents (33, 34) (supplemental Fig. 1A); and 2) that a Michael adduct forms between an HDAC cysteinyl thiol and the electrophilic β-carbon of cyclopentenone PGs (supplemental Fig. 1, B and C).

FIGURE 1.

15d-PGJ2-B forms a covalent adduct preferentially with cellular class I HDAC1, -2, and -3. A, time course of HDAC1, -2, -3, and -8 modification by 15d-PGJ2-B corresponding to the signal density of the immunoblots in panel B. B, immunoblots (IB) showing NeutrAvidin pulldown (NA Pulldown) of HDAC·15d-PGJ2-B (arrows) and total HDAC8 (loading control) from HEK293 cells treated with 15d-PGJ2-B (5 μm). Cells were treated at individual time points (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 3 h) and harvested at the same time. WCL, whole cell lysates.

Mammalian class I HDACs and yeast RPD3 have conserved Cys residues. Thus, some other members of this family, besides HDAC1, might be alkylated (carbonylated) by reactive carbonyl species. We found that 15d-PGJ2-B also alkylated RPD3, a class I HDAC homolog in S. cerevisiae (see Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. 1D). Alkylation of RPD3 and HDAC1, -2, and -3 was concentration-dependent from 1 to 10 μm 15d-PGJ2-B (see Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. 1D). Covalent modification of HDAC1, -2, and -3, but not HDAC8, occurred uniformly in several cell lines, e.g. HCT116, MCF7, A549, HL-60, and HEK293.

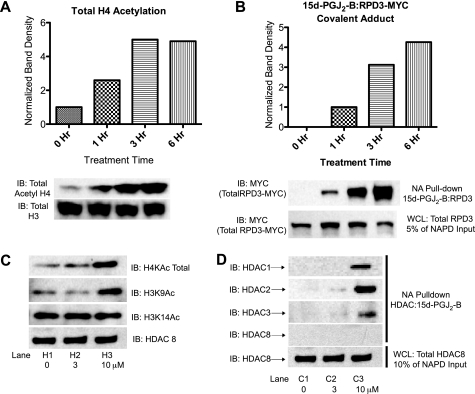

FIGURE 5.

Cellular histone acetylation patterns change as a function of carbonylation of HDACs and RPD3. A, immunoblot (IB) of total acetyl-histone H4 in S. cerevisiae treated for 0, 1, 3, and 6 h with 15d-PGJ2-B (25 μm). H4 acetylation rose ∼5-fold by 3 h of treatment. B, RPD3 modified by 15d-PGJ2-B (NeutrAvidin pulldown (NA pulldown)) during the same experiment as panel A. WCL, whole cell lysates. C, immunoblots of histone H4 and histone H3 acetylation in A549 cells treated with 3 and 10 μm 15d-PGJ2-B, when compared with 10 μm biotin as a control treatment. D, HDAC1, -2, and -3 modified by 15d-PGJ2-B (NeutrAvidin pulldown) during the same experiment as panel C.

Alkylation (Carbonylation) of Conserved Cysteine Residues in HDAC1, -2 and -3 Antagonizes Their Deacetylase Activity and Transcriptional Co-repressor Function

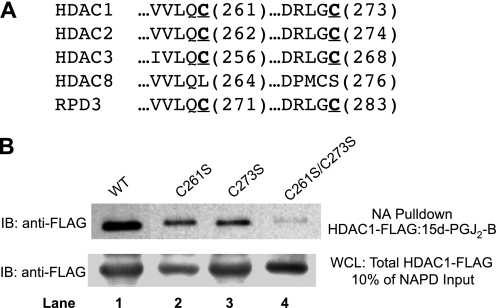

Differential alkylation (carbonylation) of some, but not every class I HDAC, implies that their covalent modification is not indiscriminate and may involve particular, conserved cysteinyl thiol residues. Our data (Fig. 1) argue against the cysteine residues corresponding to Cys151 of HDAC1 because these catalytic cysteines are shared by all class I HDACs, including HDAC8. Protein sequence alignment revealed two other cysteine residues in HDAC1, -2, and -3 and RPD3 that we considered candidates for modification (Fig. 2A). These correspond to Cys261 and Cys273 residues of HDAC1, which appear to be surface-accessible, according to homology models (35). Notably, HDAC8, which was not susceptible to alkylation by 15d-PGJ2-B, has a Leu substituted for Cys at one conserved position and a displaced Cys with a different flanking residue at the other conserved position. The motif surrounding Cys273 of HDAC1 shares appreciable homology with motifs surrounding Cys residues alkylated by cyclopentenone prostaglandins in other proteins, such as the T-loops of the IκB kinase β and LKB1 Ser/Thr kinases, h-Ras, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and the p50 and p65 subunits of NFκB. To determine whether any of these cysteine residues reacted with 15d-PGJ2-B, we used site-directed mutagenesis of an HDAC1-FLAG construct to make Cys → Ser mutants, C261S and C273S. Plasmids expressing these HDAC1-FLAG mutants were transfected into HEK293 cells, which were subsequently treated with 5 μm 15d-PGJ2-B. When compared with the wild type HDAC1-FLAG, each of these single-mutant HDAC1-FLAG proteins formed ∼70% less covalent adduct with 15d-PGJ2-B (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3 versus lane 1). Each showed comparable alkylation, consistent with reaction at Cys261 and Cys273. An HDAC1-FLAG double-mutant, C261S/C273S, showed ∼95% less alkylation by 5 μm 15d-PGJ2-B (Fig. 2B, lane 4 versus lane 1), supporting the conclusion that both Cys261 and Cys273 are susceptible to alkylation (carbonylation) by α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. A corresponding set of Cys → Ala mutants gave similar results. There was a low but detectable formation of 15d-PGJ2-B adduct with the C261S/C273S HDAC1 double mutant, ∼5%, implying that other sites may be alkylated to a minor degree.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of electrophile-sensitive, conserved cysteine residues of HDAC-FLAG via site-directed mutagenesis. A, the amino acid sequence alignment of class I HDACs and RPD3 shows cysteine residues homologous in HDAC1, -2, -3, and RPD3 but not HDAC8. B, two, single mutants of HDAC1, C261S and C273S, and one double mutant C261S/C273S were transfected into HEK293 cells followed by treatment with 15d-PGJ2-B. The lower panel represents HDAC1-FLAG in whole cell lysates (WCL), whereas the upper panel represents HDAC1-FLAG·15d-PGJ2-B isolated by biotin capture on NeutrAvidin beads. Immunoblotting (IB) with anti-FLAG antibodies shows that the wild type (WT) HDAC1-FLAG protein was most extensively carbonylated; the C261S and C273S proteins were partially carbonylated; and the C261/273S protein was negligibly carbonylated. NA Pulldown, NeutrAvidin pulldown; NAPD Input, NeutrAvidin pulldown input.

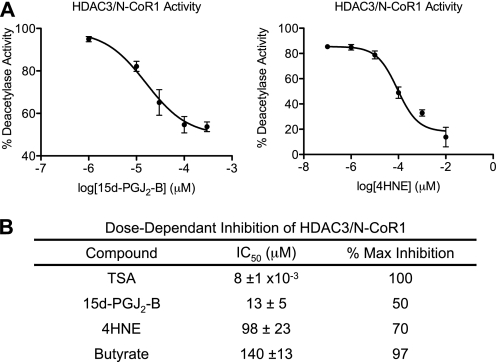

To better understand the functional consequences of HDAC alkylation by RCS, we tested in vitro deacetylase activity of HDAC3·N-CoR1 treated with 4HNE, an enal that can be generated by oxidative stress (36), and 15d-PGJ2-B. Inhibition of the HDAC3·N-CoR1 complex by these RCS was concentration-dependent and intermediate in potency, relative to TSA and butyrate. Half-maximal inhibition (IC50) required 10 nm TSA, 13 μm 15d-PGJ2-B, 98 μm 4HNE, and 140 μm butyrate (Fig. 3). Maximal inhibition of HDAC3·N-CoR1 by 15d-PGJ2-B and 4HNE is 50 and 70%, respectively. The lack of complete inhibition upon alkylation suggests that inhibition of deacetylase activity is not likely the major consequence of HDAC alkylation yet implies that its modifiable thiolate residues are near the catalytic site or that they are allosterically linked to the catalytic site.

FIGURE 3.

Dose-dependent modulation of HDAC3·N-CoR1 deacetylase activity by electrophilic enones (15d-PGJ2-B) and enals (4HNE). A, electrophilic enone 15d-PGJ2-B (IC50 13 ± 5, n = 9) and enal 4HNE (IC50 98 ± 23, n = 7) inhibit HDAC3·N-CoR1 complex in a radiological assay. The [3H]acetyl-histone (15,000 dpm/reaction) substrate was incubated with recombinant HDAC3·N-CoR1 (300 ng) in the presence of vehicle, 15d-PGJ2-B (1, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μm), or 4HNE (0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000 μm). Activity is measured as the percentage of vehicle-treated HDAC activity, and the mean ± S.E. are depicted. B, table comparing IC50 values obtained from the radiological assay described in panel A.

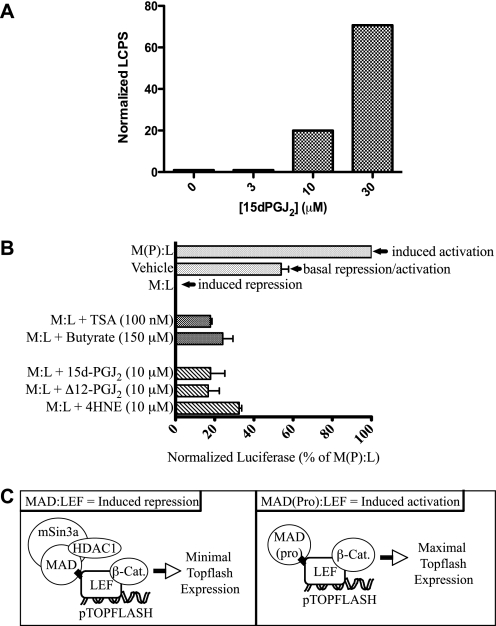

Class I HDACs in co-repressor complexes play a major role in transcriptional silencing (18, 37). Thus, we hypothesized that alkylation and inhibition of HDACs by 15d-PGJ2 would antagonize their co-repressor function in HEK293 cells harboring an STF luciferase reporter with seven LEF/TCF-binding sites (38). LEF1 recruits HDAC1 as a co-repressor of transcription in this system. Others have reported that inhibition of HDAC1 by TSA relieves LEF1-mediated repression and converts it to a transcriptional activator (23). If 15d-PGJ2-B or other RCS inhibited HDAC1 in an analogous experiment, LEF1 would be similarly activated, leading to enhanced luciferase expression. Consistent with this hypothesis, luciferase expression rose 20–80-fold as a function of 15d-PGJ2 concentration in HEK293 cells stably expressing an STF reporter construct (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Electrophilic enones (15d-PGJ2 and Δ12-PGJ2) and enals (4HNE) antagonize the transcriptional repression of LEF1/β-catenin by HDACs. A, HEK293 cells, harboring a stably integrated STF luciferase reporter construct that is transactivated by nuclear LEF/β-catenin, were treated with 0–30 μm 15d-PGJ2 for 18 h, which led to increased luciferase expression, in the absence of WNT ligand. LCPS, luciferase counts per second. B, STF3a cells, which harbor the STF luciferase reporter construct, plus a construct for stably secreting WNT3a, were transfected with a MAD·LEF chimera or a mutant form MAD(Pro)·LEF for 24 h followed by treatment for 18 h with 15d-PGJ2,Δ12-PGJ2, 4HNE,or the known HDAC inhibitors TSA or butyrate. The bar labeled Vehicle represents basal expression of luciferase; the bar labeled M(P):L represents a fully derepressed system; the bar labeled M:L represents a repressed system. Luciferase activity in all conditions is inversely proportional to LEF1 repression of the pTOPFLASH gene. The enones (15d-PGJ2, Δ12-PGJ2) and the enal (4HNE) antagonized the HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression in cells expressing the MAD·LEF1 chimera, comparably to the HDAC inhibitors TSA and butyrate (bars labeled M:L plus agent). C, scheme depicting the effect of MAD·LEF and mutant MAD(Pro)·LEF chimeras on HDAC-mediated co-repression at the pTOPFLASH promoter. Left panel, MAD·LEF chimera enables LEF repression by associating with mSin3a containing HDAC1. Inhibition of HDAC1 in this system leads to LEF activation. Right panel, the MAD(Pro)·LEF mutant chimera cannot associate with mSin3a, and therefore, LEF is in a minimally repressed state, i.e. it enables LEF/β-catenin (β-Cat.) transactivation.

To determine whether 15d-PGJ2, and related RCS, act independently of other, upstream WNT signaling events, we also used STF3a cells, a cell line that stably expresses both the STF luciferase reporter gene and the wnt3a gene. In these cells, constitutively secreted WNT3a binds to FRZL, its cognate receptor, leading to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and transactivation of the STF luciferase reporter gene (26). In conjunction, we used plasmids expressing chimeric MAD·LEF1 genes. The MAD component of the chimera associates with mSin3a in a multiprotein complex that recruits HDAC1 as a co-repressor (Fig. 4C) (18). In transfected STF3a cells, the MAD·LEF1 chimera protein caused maximal repression of the luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 4B, M:L bar), relative to the basal luciferase activity in mock-transfected STF3a cells (Fig. 4B, Vehicle bar). Conversely, transfection and expression of a mutant, dysfunctional MAD variant, MAD(Pro)·LEF1, which cannot recruit HDAC1 to co-repressor complexes, caused maximal derepression (i.e. induction) of the luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 4B, M(P):L bar). As shown (Fig. 4B, M:L bar), nuclear β-catenin in STF3a cells was unable to transactivate luciferase reporter gene expression because of the dominant effect of HDAC1 recruited by the MAD·LEF1 chimera in the co-repressor complex (23). Upon treating MAD·LEF1-transfected STF3a cells with a panel of representative RCS, including 15d-PGJ2 (10 μm), Δ12-PGJ2 (10 μm), or 4HNE (10 μm), we observed recovery of LEF1·β-catenin transcriptional activity (Fig. 4B, cross-hatch bars versus M:L dotted bar), similar in magnitude to MAD·LEF1-transfected STF3a cells treated with known inhibitors of HDACs, TSA (100 nm) and butyrate (150 μm) (Fig. 4B, checkered bars versus M:L dotted bar).

HDAC Alkylation by 15d-PGJ2 Promotes Changes in Histone Acetylation and Promotes Activation of Genes That Are Induced by 15d-PGJ2

To substantiate our observation that RCS inhibited HDAC activity and to determine the biological outcome of this inhibition, we first measured changes in histone acetylation in yeast and mammalian cells exposed to 15d-PGJ2-B. Immunoblot analysis showed that total histone H4 acetylation increased, coincident with covalent modification of RPD3 in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 5, A and B). Moreover, 15d-PGJ2-B differentially altered the acetylation pattern at specific lysine residues of histone H3 in A549 cells concurrent with alkylation of HDACs in A549 cells (Fig. 5D). For instance, levels of H3K9Ac rose, whereas H3K14Ac remained constant (Fig. 5C).

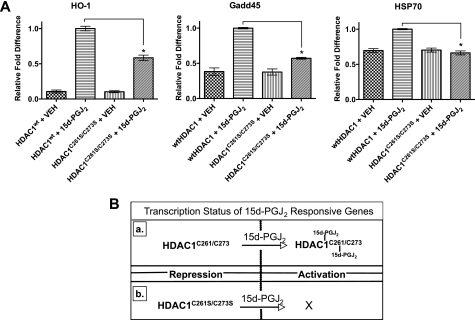

Because H3K9Ac is associated with transcriptionally active chromatin (39, 40), we sought to determine whether carbonylation of HDACs regulates genes that are sensitive to 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 6B). Various cell lines increase expression of genes associated with redox regulation (e.g. γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase), heat shock response (e.g. HSP70, HO-1), and p53-responsive genes (e.g. Gadd45)) when treated with the cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 (41). The mechanisms of 15d-PGJ2-mediated gene up-regulation are not fully understood, yet transcriptional repression of these genes is governed in part by altering the post-translational acetylation of histones by HDACs and activation of appropriate transcription factors. Therefore, the presence of 15d-PGJ2 may not only promote activation of transcription factors but may also lead to coordinate disruption of HDAC-mediated gene repression. To test this hypothesis, we transiently transfected A549 cells with either wild type HDAC1 (HDAC1WT) or 15d-PGJ2-insensitive mutant HDAC1 (HDAC1C261S/C273S). Both were treated with either vehicle or 15d-PGJ2 (10 μm) for 24 h. We then measured the mRNA levels of HO-1, Gadd45, and HSP70 via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Consistent with previous reports, 15d-PGJ2 induced expression of HO-1, Gadd45, and HSP70 genes in cells harboring HDAC1WT when compared with cells treated with vehicle alone (41). Consistent with our hypothesis, A549 cells expressing HDAC1C261S/C273S are less responsive to 15d-PGJ2 treatment, inducing less expression of HO-1 (42% ± 4%), Gadd45 (43% ± 1%), and HSP70 (28% ± 1%) when compared with 15d-PGJ2-treated cells harboring HDAC1WT (Fig. 6A). The observed expression of these genes in cells expressing HDAC1C261S/C273S is likely due to endogenous wild type HDACs competing with the transfected mutant.

FIGURE 6.

Genes induced by 15d-PGJ2 are activated upon carbonylation of HDACs by 15d-PGJ2. A, A549 cells were transiently transfected with HDAC1wt or HDAC1C261S/C273S expression plasmids, and 24 h later, they were treated with either vehicle (VEH) or 15d-PGJ2 (10 μm). Cells were incubated for 24 h, and then mRNA expression analysis of HO-1, Gadd45, HSP70, and housekeeping genes GAPDH and β-actin were measured via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Depicted is the mean of the relative -fold difference in an expression using ΔΔCT method of analysis and by normalizing this value to 1.0 for cells harboring HDACWT and treated with 15d-PGJ2. Error bars are S.E., and asterisks denote statistical significance (p < 0.05) as determined by two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test. B, schematic depicting the transcriptional status of genes that are sensitive to 15d-PGJ2 according to our data in panel A. Inset a shows how gene activation is in part driven by the alkylation of Cys261 and Cys273 of HDAC1, whereas activation is blunted due to HDAC1 insensitivity to 15d-PGJ2 as shown in inset b.

DISCUSSION

We conclude that RCS, typified by cyclopentenone prostaglandins of the J- and A-series, alkylate a subset of mammalian class I HDACs that include HDAC1, -2, -3, as well as RPD3, a yeast class I HDAC homolog. Alkylation (carbonylation) occurred at two conserved cysteine residues, corresponding to Cys261 and Cys273 in HDAC1. HDAC8, which differs from other class I HDACs in this regard, was not susceptible to alkylation. Our results concur with a recent mass spectrometry survey (42), which found HDAC1 and -2, but not HDAC8, among 417 cellular proteins modified by 100 μm 4HNE (43). HDAC2 can also be nitrosylated at Cys262 and Cys274 (44, 45). Because residues sensitive to ROS and reactive nitrogen species are often sensitive to modification by RCS, our results suggest that the homologous cysteine residues in HDAC1 and HDAC3 as well as yeast RPD3 could be sensitive to nitrosylation and oxidation.

RCS (15d-PGJ2 and 4HNE) that carbonylated HDACs also inhibited deacetylation of [3H]acetyl-histones, for example, HDAC3·N-CoR1. Conversely, they did not inhibit deacetylation of synthetic, fluorescent tetrapeptide substrates. These results imply that carbonylation of redox-sensitive cysteine residues, e.g. Cys261 and Cys273 in HDAC1, disrupts interactions between HDACs and their endogenous histone substrates, rather than disrupting their catalytic site per se. Moreover, these data indicate that a catalytic cysteine, corresponding to Cys151 in HDAC1, was not susceptible to alkylation by RCS. If this catalytic cysteine were affected, one would expect inhibition of catalysis, regardless of substrate type. Likewise, one would expect to see alkylation of all class I HDACs that share the conserved active site cysteine, including HDAC8 (Cys153); however, this was not the case.

Disruption of cellular deacetylase activity by RCS coincided with changes in chromatin dynamics, the function of HDACs situated in co-repressor complexes, and derepression/activation of RCS-sensitive genes. For instance, alkylation of HDACs in mammalian cells: (i) altered the so called histone code, e.g. differentially elevating the level of H3K9Ac, but not H3K14Ac alkylation; (ii) antagonized the transcriptional co-repressor function of HDAC1 in a LEF1·β-catenin model system; and (iii) promoted transcription of HDAC1-repressed genes, HO-1, Gadd45, and HSP70.

Overall, our results suggest that some DNA-binding sites (response elements) for redox-sensitive transcription factors exist in a latent state, which is maintained by co-repressor complexes containing class I HDAC enzymes that favor heterochromatin formation via their deacetylation of histones. Carbonylation of HDAC1, -2 and -3 antagonizes their deacetylase activity, disrupts their transcriptional repression, modulates chromatin dynamics, and unmasks electrophile-response elements latent within heterochromatin. Thus, cellular redox signaling can involve liberation of latent transcription factors (e.g. KEAP·NRF2, NFκB, LEF/β-catenin, p53) coordinated with liberation of their DNA recognition sites in gene promoters. Oxidative stress from various pathophysiological conditions is not uniformly cytotoxic. Our model of redox signaling suggests a mechanism to coordinate the activity of co-repressor complexes containing HDAC1, -2, and -3 and latent, redox-sensitive transcription factors. This may enable cells to stratify their anti-oxidant response according to the gravity, or nature, of the oxidant threat. For example, inflammation consists of a “wounding” phase where redox stress annihilates pathogens and a “healing” phase where redox stress influences repair and regeneration of damaged host tissue (46). The transition between phases depends on gradual exhaustion of inflammatory mediators and conversion of certain pro-inflammatory mediators, e.g. PGD2, into anti-inflammatory metabolites (32, 47, 48). Elements of the inflamed site itself, e.g. ROS, albumin, fibroblasts and neutrophils, orchestrate this conversion (27, 49–51). ROS cause non-enzymatic peroxidation of essential fatty acids, like arachidonic acid (52). Arachidonic acid hydroperoxides transform readily into RCS (6, 53) that include acrolein (2-propenal (54, 55), 4HNE (43), and cyclopentenone prostaglandins, PGA2, Δ12-PGJ2, and 15d-PGJ2 (56). Covalent modification of NFκB and IκB kinase α/β proteins by these RCS (protein carbonylation) seems to be a “switch” to terminate inflammation (12, 29, 57–59). Could carbonylation also be a switch to initiate repair and regeneration of tissue damaged by inflammation? If so, which proteins would be carbonylated, and how might their involvement sometimes favor tumorigenesis? We investigated HDACs, based first, on reports that cyclopentenone prostaglandins accumulated in the nucleus and associated irreversibly with chromatin and other nuclear proteins (13), and second, on reports that HDACs mediate WNT/β-catenin signaling (23), a determinant of cell growth, differentiation, and disease.

Redox stress and inflammatory processes create a milieu rich in ROS and RCS. As an investigative tool to study HDAC modification by RCS, we have used cyclopentenone prostaglandins and 4-hydroxynonenal to represent RCS generated during lipid oxidation and arachidonic acid metabolism, although other RCS are undoubtedly present during redox stress and inflammation (2). Exposure of cells in vitro to a single, bolus addition of separate RCS (1–10 μm) is difficult to relate directly to progressive, cumulative exposures that occur in vivo during various types of oxidative stress. Quantification of RCS is complicated by their reactivity. Because RCS conjugate with peptides (GSH) and proteins, analysis of the level of “free” compound does not necessarily reflect, and more likely underestimates, the concentrations and fluxes of various RCS. Carbonylation is a marker of oxidative stress, and chronic exposure or elevated concentrations of RCS have been implicated in many diseases including, but not limited to, Alzheimer disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (60), arthritis, diabetes, and Parkinson disease, as reviewed by Dalle-Donne et al. (61). Although aberrant modification and dysregulation of proteins have been the major focus of most protein carbonylation studies, it is becoming more evident that RCS may play an active role in redox signaling in ways analogous to ROS-mediated signal transduction (62–65).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Dr. Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins University, for 293 STF cells; to Don Ayer, University of Utah, for helpful discussion and for the MAD·LEF constructs; to Mazin Al-Salihi, University of Utah, for useful discussion for the expression experiments; and to the David Stillman and Brad Cairns laboratories, University of Utah, for the helpful discussion for the yeast experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI 26730 (to F. A. F.). This work was also supported by the Dee Glen and Ida Smith Chair for Cancer Research.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- RCS

- reactive carbonyl species

- PG

- prostaglandin

- 15d-PGJ2

- 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2

- 15d-PGJ2-B

- 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2-biotin

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- 4HNE

- 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- STF

- SuperTOPflash®

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- WT

- wild type

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- LEF

- lymphoid enhancer factor

- TCF

- T-cell factor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medzhitov R. (2008) Nature 454, 428–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamatakis K., Pérez-Sala D. (2006) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1091, 548–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh J. Y., Giles N., Landar A., Darley-Usmar V. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M., Mori M., Niwa T., Hirata R., Furuta K., Ishikawa T., Noyori R. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 2376–2385 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salsbury F. R., Jr., Knutson S. T., Poole L. B., Fetrow J. S. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 299–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimsrud P. A., Xie H., Griffin T. J., Bernlohr D. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21837–21841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poole L. B., Karplus P. A., Claiborne A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 325–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordray P., Doyle K., Edes K., Moos P. J., Fitzpatrick F. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32623–32629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmeen A., Andersen J. N., Myers M. P., Meng T. C., Hinks J. A., Tonks N. K., Barford D. (2003) Nature 423, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu C., Chan S. L., Fu W., Mattson M. P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24368–24375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner T. M., Mullally J. E., Fitzpatrick F. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2598–2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi A., Kapahi P., Natoli G., Takahashi T., Chen Y., Karin M., Santoro M. G. (2000) Nature 403, 103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narumiya S., Ohno K., Fukushima M., Fujiwara M. (1987) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 242, 306–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narumiya S., Ohno K., Fujiwara M., Fukushima M. (1986) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 239, 506–511 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narumiya S., Fukushima M. (1986) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 239, 500–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taunton J., Hassig C. A., Schreiber S. L. (1996) Science 272, 408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassig C. A., Schreiber S. L. (1997) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassig C. A., Fleischer T. C., Billin A. N., Schreiber S. L., Ayer D. E. (1997) Cell 89, 341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knoepfler P. S., Eisenman R. N. (1999) Cell 99, 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struhl K. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jepsen K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courey A. J., Jia S. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 2786–2796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billin A. N., Thirlwell H., Ayer D. E. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6882–6890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J. M., Spencer V. A., Chen H. Y., Li L., Davie J. R. (2003) Methods 31, 12–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shechter D., Dormann H. L., Allis C. D., Hake S. B. (2007) Nat. Protoc. 2, 1445–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCulloch M. W., Coombs G. S., Banerjee N., Bugni T. S., Cannon K. M., Harper M. K., Veltri C. A., Virshup D. M., Ireland C. M. (2009) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 2189–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzpatrick F. A., Wynalda M. A. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 11713–11718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noyori R., Suzuki M. (1993) Science 259, 44–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cernuda-Morollón E., Pineda-Molina E., Cañada F. J., Pérez-Sala D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35530–35536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moos P. J., Edes K., Cassidy P., Massuda E., Fitzpatrick F. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 745–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts L. J., 2nd, Sweetman B. J. (1985) Prostaglandins 30, 383–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajakariar R., Hilliard M., Lawrence T., Trivedi S., Colville-Nash P., Bellingan G., Fitzgerald D., Yaqoob M. M., Gilroy D. W. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20979–20984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchida K., Shibata T. (2008) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gayarre J., Stamatakis K., Renedo M., Pérez-Sala D. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 5803–5808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D. F., Helquist P., Wiech N. L., Wiest O. (2005) J. Med. Chem. 48, 6936–6947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider C., Porter N. A., Brash A. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15539–15543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rundlett S. E., Carmen A. A., Kobayashi R., Bavykin S., Turner B. M., Grunstein M. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14503–14508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Q., Wang Y., Dabdoub A., Smallwood P. M., Williams J., Woods C., Kelley M. W., Jiang L., Tasman W., Zhang K., Nathans J. (2004) Cell 116, 883–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice J. C., Allis C. D. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krejcí J., Uhlírová R., Galiová G., Kozubek S., Smigová J., Bártová E. (2009) J. Cell. Physiol. 219, 677–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kondo M., Shibata T., Kumagai T., Osawa T., Shibata N., Kobayashi M., Sasaki S., Iwata M., Noguchi N., Uchida K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7367–7372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Codreanu S. G., Zhang B., Sobecki S. M., Billheimer D. D., Liebler D. C. (2009) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 670–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esterbauer H., Eckl P., Ortner A. (1990) Mutat. Res. 238, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nott A., Watson P. M., Robinson J. D., Crepaldi L., Riccio A. (2008) Nature 455, 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colussi C., Mozzetta C., Gurtner A., Illi B., Rosati J., Straino S., Ragone G., Pescatori M., Zaccagnini G., Antonini A., Minetti G., Martelli F., Piaggio G., Gallinari P., Steinkuhler C., Clementi E., Dell'Aversana C., Altucci L., Mai A., Capogrossi M. C., Puri P. L., Gaetano C. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19183–19187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nathan C. (2002) Nature 420, 846–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serhan C. N., Chiang N., Van Dyke T. E. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilroy D. W., Colville-Nash P. R., Willis D., Chivers J., Paul-Clark M. J., Willoughby D. A. (1999) Nat. Med. 5, 698–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shibata T., Kondo M., Osawa T., Shibata N., Kobayashi M., Uchida K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10459–10466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serhan C. N., Savill J. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buckley C. D., Pilling D., Lord J. M., Akbar A. N., Scheel-Toellner D., Salmon M. (2001) Trends Immunol. 22, 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esterbauer H., Schaur R. J., Zollner H. (1991) Free Rad. Biol. Med. 11, 81–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West J. D., Marnett L. J. (2006) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19, 173–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uchida K., Kanematsu M., Morimitsu Y., Osawa T., Noguchi N., Niki E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16058–16066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson M. M., Hazen S. L., Hsu F. F., Heinecke J. W. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 424–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y., Morrow J. D., Roberts L. J., 2nd (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10863–10868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valacchi G., Pagnin E., Phung A., Nardini M., Schock B. C., Cross C. E., van der Vliet A. (2005) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straus D. S., Pascual G., Li M., Welch J. S., Ricote M., Hsiang C. H., Sengchanthalangsy L. L., Ghosh G., Glass C. K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4844–4849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ji C., Kozak K. R., Marnett L. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18223–18228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rahman I., van Schadewijk A. A., Crowther A. J., Hiemstra P. S., Stolk J., MacNee W., De Boer W. I. (2002) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 166, 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dalle-Donne I., Giustarini D., Colombo R., Rossi R., Milzani A. (2003) Trends Mol. Med. 9, 169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levonen A. L., Landar A., Ramachandran A., Ceaser E. K., Dickinson D. A., Zanoni G., Morrow J. D., Darley-Usmar V. M. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cattaruzza M., Hecker M. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 273–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong C. M., Cheema A. K., Zhang L., Suzuki Y. J. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong C. M., Marcocci L., Liu L., Suzuki Y. J. (2010) Antiox. Redox Signal. 12, 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.