Abstract

P2X7 receptors (P2X7R) are ATP-gated calcium-permeable cationic channels structurally unique among the P2X family by their much longer intracellular C-terminal tail. P2X7Rs show several unusual biophysical properties, in particular marked facilitation of currents and leftward shift in agonist affinity in response to repeated or prolonged agonist applications. We previously found the facilitation at rat P2X7R resulted from a Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent process and a distinct calcium-independent process. However, P2X7Rs show striking species differences; thus, this study compared the properties of ATP-evoked facilitation of currents in HEK293 cells transiently expressing the human or rat P2X7R as well as rat/human, human/rat chimeric, and mutated P2X7Rs. Facilitation at the human P2X7R was 5-fold slower than at the rat P2X7R. Facilitation did not resulting from an increase of receptor addressing the plasma membrane. We found the human P2X7R shows only calcium-independent facilitation with no evidence for calmodulin-dependent processes, nor does it contain the novel 1-5-16 calmodulin binding domain present in the C terminus of rat P2X7R. Replacement of three critical residues of this binding domain from the rat into the human P2X7R (T541I, C552S, and G559V) reconstituted the Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent facilitation, leaving the calcium-independent facilitation unaltered. The leftward shift in the ATP concentration-response curve with repeated agonist applications appears to be a property of the calcium-independent facilitation process because it was not altered in any of the chimeric or mutated P2X7Rs. The absence of Ca2+-dependent facilitation at the human P2X7R may represent a protective adaptation of the innate immune response in which P2X7R plays significant roles.

Keywords: Biophysics, Calcium/Calmodulin, Channels/Ion, Receptors, ATP, P2X7 Receptors, Facilitation, Ionotropic Receptor, Species Orthologs

Introduction

ATP-gated P2X7 receptors (P2X7R)3 are calcium-selective channels that show many structural and functional differences from the other receptors (P2X1–P2X6) of the P2X family. One of the first differences is tissue expression, although P2X1–P2X6R are primarily found in neurons (1, 2). P2X7Rs are mainly expressed by cells from hematopoietic lineage such as mast cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and epidermal Langerhans cells (3, 4). They are also known to be localized and functional in micro- and macroglial cells (5–8). Unlike other P2X receptors that are activated by low doses of their natural agonist ATP (<10 μm), P2X7 receptors are activated by high concentrations of ATP (>100 μm) (1). Moreover, it is noticeable that among all the members of the P2X family, only P2X7Rs show no desensitization to agonist application (1). Indeed, cellular expression of P2X7Rs in immune cells, the fact that receptors never desensitize, and that high concentrations of ATP are needed to activate them led us to postulate that these receptors could act as molecular sensors for dangerous conditions in the cellular environment, i.e. cellular disruption in damaged or infected tissues (9). P2X7R activation at injured or inflammation sites is the main physiological event for the rapid maturation and release of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β and interleukin-18 (9, 10). P2X7R activity has also been demonstrated to be involved in chronic pain associated with inflammatory diseases (11, 12), and these receptors are therefore the target of new anti-inflammatory antagonists developed by different pharmaceutical companies (13–16).

Molecular cloning of P2X7Rs revealed a typical P2X subunit structure with a short intracellular N-terminal tail and two transmembrane segments (TM1 and TM2) connected by a large ectodomains supporting agonist/antagonist binding (1, 3). However, P2X7Rs have a long intracellular C-terminal end, being 120–200 amino acids longer compared with other P2X receptors (3, 17). This long C-terminal end has been proposed to be responsible for most of the specific biophysical properties of the P2X7R with numerous functions such as connecting the receptor to structures responsible for the large pore formation (3, 17), recently proposed as being pannexin-1 (18), the interaction with adaptor and signaling proteins (19, 20), the regulation of P2X7R trafficking to the plasma membrane (21, 22), and the modulation of channel gating (23). Recently, we demonstrated that rat P2X7R C terminus is also displaying a novel 1-5-16 calmodulin-binding motif responsible for a calcium-dependent facilitation (24). Therefore, Ca2+ entry through activated rat P2X7R enhances the activity of the same receptors. This phenomenon could be considered as a hypersensitization process making the intracellular response bigger when re-exposed to the agonist. P2X7R show species differences concerning sensitivity or selectivity of agonists and antagonists (25, 26), as well as some biophysical properties (1, 27).

This study is aimed to better characterize biophysical properties of the human P2X7R, and particularly its facilitation phenomenon, which is of primary importance in different physio- and pathological conditions. We compared P2X7R currents generated in HEK293 cells expressing recombinant human and rat cDNA for repeated agonist applications, and we analyzed whether the facilitation process was responding to the same molecular determinants in both species. To explore the particular role of species-specific responses due to sequence variations, we generated human/rat chimeric receptors and human P2X7R mutants by site-directed mutagenesis. We also used co-immunoprecipitation assays to assess the interactions between P2X7R and calmodulin. Over all, our results indicate that the rat C terminus is responsible for the P2X7R Ca2+-dependent facilitation due to the presence of a calmodulin-binding motif. This phenomenon is absent in human P2X7R because of the sole substitution of three amino acids resulting in the nonbinding of calmodulin. Indeed, human P2X7Rs only display a Ca2+-independent facilitation that is responsible for a reduced activation of the receptor. This property of the human P2X7R could represent a protective adaptation of the innate immune response in which P2X7R plays a significant role and should be taken into account when using animal models.

We also found that an 18-amino acid domain rich in cysteines in the juxtamembrane C terminus, conserved in all P2X7R orthologs, is critical for the general process of current facilitation. This domain might represent a hinge region necessary for the conformational changes occurring during both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent facilitation processes. Our results provide essential knowledge that should enable a better understanding of the still poorly known P2X7R structure-function relationships and on its different responses to agonists depending on the species.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Antibodies

Culture media, sera, and other cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen. ATP, Triton X-100, salts, and chemicals for the solutions and Kodak films were obtained from Sigma. Rabbit anti-Glu-Glu and rabbit IgG antibodies were from Bethyl Laboratories; monoclonal mouse anti-calmodulin primary antibodies were from Millipore; goat anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Dako, and ECL-Plus kit was from GE Healthcare.

Cell Culture, Transfection, Chimeric Receptors, and Site-directed Mutagenesis

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's/F-12 medium, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 2 mm l-glutamine at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were grown to 80–90% confluence and transiently transfected with 1 μg of cDNA encoding rat or human P2X7 receptors (3) and GFP expression plasmid (0.1 μg, for fluorescent detection of transfected cells) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). They were then plated into either 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks (for co-immunoprecipitation experiments) or onto 13-mm glass coverslips (for electrophysiological studies).

Point mutations were introduced into human or rat P2X7R constructs in pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) using the PCR overlap extension method and Accuzyme proofreading DNA polymerase (Bioline, UK). Chimeric receptors were produced as described previously (17). Nucleotide changes in the human P2X7R coding sequence responsible for Thr-541 to Ile-541, Cys-552 to Ser-552, and Gly-559 to Val-559 amino acids in the protein were achieve using overlapping oligonucleotides; the sequences are available upon request. The 54 nucleotides (1084–1137 of the rat P2X7R open reading frame) coding for the 18-amino acid cysteine-rich region from Cys-372 to Val-389 (CCRSRVYPSCKCCEPCAV) of the receptor were deleted by overlapping PCR as described previously (28). Wild-type and mutated rat and human P2X7 receptors bore C-terminal Glu-Glu (EE) epitope tags (EYMPME). The full coding regions of the constructs used in this study were verified by DNA sequencing.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were performed 24–48 h after transfection by the patch clamp technique. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) to a resistance of 4–6 megohms. Currents were recorded in the whole-cell configuration, under voltage clamp mode at room temperature using a MultiClamp 700A patch clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices), and analog signals were filtered at 10 kHz and digitized using a 1322A Digidata converter. Cell capacitance and series resistances were electronically compensated. Membrane potential was held at −60 mV. Agonist (ATP) was applied using an RSC 200 fast-flow delivery system (BioLogic Science Instruments, France). Facilitation curves were built by measuring the maximal current at each time point from initiation of ATP application (prolonged applications) or by measuring instantaneous current during the initial 10-s application of ATP and calling this “0,” and the current amplitude at end of each 10-s pulse (at 40 s intervals) was measured and plotted as a function of total duration of ATP application. Concentration-response curves to ATP were realized by an initial application of maximum ATP (10 mm) and then by applying decreasing concentrations of agonist, after full P2X7R facilitation. Concentration-responses curves were plotted using Origin Microcal 6.0 software (OriginLab) and EC50 defined using the sigmoidal equation provided by this software.

Solutions

The external physiological saline solution (PSS) had the following composition (in mm): 147 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 13 d-glucose, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2. Agonist solutions were prepared in this PSS at the concentration indicated in the figure legends. Control intracellular solution (CTL) had the following composition (in mm): 147 NaCl, 10 HEPES, EGTA. In the BAPTA internal solution (BAPTA), 5 mm BAPTA was used in place of EGTA. Osmolarity and pH values were 295–315 mosm and 7.3, respectively. Five min was allowed after achieving whole-cell conditions before beginning experimental protocols to obtain complete dialysis of intracellular solutions.

Fluo-4 Assays

Changes in free intracellular calcium concentration were measured with the fluorescent indicator Fluo-4 AM. A Nikon confocal microscope with Fluar ×20 objective (Nikon, Surrey, UK) was used. Cells plated onto 13-mm coverslips were loaded for 45 min at 37 °C with 1 μm Fluo-4AM and 0.06% pluronic acid. Cells were superfused (2 ml/min) with the same solution used for whole-cell recordings, and agonist was applied by gravity to the superfusion fluid. Images were acquired at 4-s intervals; 20 cells in the field of view were measured for 150 s in each experiment and then averaged to obtain the mean fluorescence signal.

Plasma Membrane Versus Cytosolic and Endomembranes Protein Expression

Cells were washed twice in PBS (Ca2+- and Mg2+-free), scraped, and then transferred into centrifuge tubes containing 1.5 ml of lysis buffer (40 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 250 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, and 2% protease inhibitor mixture (v/v)). Samples were homogenized on ice with an ultra-turax for 15 s at 13,000 rpm and centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant fraction was considered as being the cytosolic and endomembrane-enriched fraction, which is characterized by the presence of soluble proteins such as β-actin and the endomembrane (trans-Golgi network, endosomes, and endocytosis vesicles) protein marker adaptin-β. The pellet was resuspended in a detergent-containing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% deoxycholate, 1% Tergitol® solution (type Nonidet P-40), 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 2% protease inhibitor mixture (v/v)), incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant fraction was considered as the plasma membrane-enriched extract. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid method. Protein samples (15 μg for total cell lysates and 30 μg for cytosolic/endomembranes and plasma membrane fractions) were diluted into the sample buffer under reducing conditions, then boiled for 3 min, separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels, and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After membrane saturation (>12 h) at 4 °C in 5% nonfat milk/Tris-buffered saline solution containing 0.5% Tween 20 (TTBS), the membrane was incubated 2 h with the primary rabbit antibody anti-EE (1:1,000), β-actin-HRP-conjugated (1:2,000), or mouse anti-adaptin-β (1:5,000) in a 5% nonfat milk/TTBS solution. The membrane was further incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. ECL was used for immunodetection.

Cell-surface Protein Labeling by Impermeant Biotin

Cell-surface protein was labeled with impermeant biotin using EZ-link (Pierce). Confluent cells (three wells of a 6-well plate) were washed twice in PBS-CM (PBS with 1 mm CaCl2 and 0.5 mm MgCl2, pH 8.0), and 1 mg/ml EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin was added for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed once with PBS-CM, and 50 mm Tris-HCl in PBS was added to quench the reactions for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were scraped from the wells in cell lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.40, 1% Nonidet P-40, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA) with protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min to pellet debris. Total protein samples were removed and assayed for protein content using the Bradford reagent (Sigma). Biotinylated surface protein in the cell lysate was bound to NeutrAvidin-agarose resin (Pierce) by rotating 3 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times in lysis buffer; SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added, and the samples were boiled for 5 min at 95 °C to release purified cell-surface proteins. Samples were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels according to standard methods and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols, and proteins were visualized using anti Glu-Glu primary antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (both at 1:3,000 dilution). HSP-70 was detected using a monoclonal mouse antibody (1:500 dilution) and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000 dilution) and was used as a negative control for biotinylation of intracellular proteins. This was followed by detection using the ECL-plus kit with a ChemiDoc XRS Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Gels were analyzed by densitometry measurements using Quantity One program (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescence Assays

Cells were transfected with GFP and P2X7R-ee as described above and plated onto coverslips; cells were examined 48 h later. Cells were washed twice with PBS followed by fixation (4% v/v formaldehyde in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with blocking solution (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.3% bovine serum albumin in PBS) for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with primary antibody against the EE-tag (1:1,000 in the blocking solution) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, anti-rabbit IgG TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Sigma) was applied for 30 min. After a brief rinse in H2O, coverslips were mounted on slides with Gold antifade reagent. Cells were photographed using Nikon Eclipse TE300 confocal ×60 objective and EZ-C1 software (Nikon UK); there were no differences between human and rat P2X7R protein localization when expressed in HEK293 cells showing intense plasma membrane-delimited expression.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assays

Two days after transfection, HEK293 cells previously plated in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks were washed twice with 15 ml of PSS, and ATP (5 mm) was then added in PSS for 45 s. Solution was immediately removed, and the cells were scraped and lysed in the presence of 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA), containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Applied Science) for 1 h at 4 °C. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove insoluble debris. Total protein samples were removed and assayed for protein content using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using the ExactaCruz FTM (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The supernatants obtained from the cell lysate centrifugation (1 ml) were precleared with 40 μl of rabbit IP matrix beads for 1 h. Two types of IP antibody-IP matrix complexes were prepared and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Each complex contained 500 μl of PBS solution, 40 μl of IP matrix beads, and 2 μg of antibodies. In one complex the antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-EE to pull down P2X7 receptors Glu-Glu-tagged, and the other complex was done using rabbit IgG as a negative control. Matrixes were centrifuged, and pellet matrixes were washed two times in PBS prior to adding the samples. Samples were separated in 2 volumes (500 μl) and incubated with each of the two IP antibody-IP matrix complexes overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, samples were centrifuged, and the pellet was washed five times with PBS. Pellets were resuspended in 35 μl of 2× denaturant (SDS) and reducing (dithiothreitol) electrophoresis buffer and boiled for 3 min. IP samples were loaded, as well as total cell lysates in 10% polyacrylamide gels (5 μg of total protein for P2X7 receptor identification and 2 μg for calmodulin identification), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols. P2X7 proteins were visualized using polyclonal rabbit anti-EE primary antibody and anti-rabbit ExactaCruz FTM-HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (both at 1:2,000 dilution), and calmodulin proteins were visualized using monoclonal mouse anti-calmodulin primary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) and rabbit anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution), followed by detection using the ECL-plus kit and Kodak Bio-Max MS film. Control Western blots and co-IP experiments were performed in plain HEK293 cells not expressing any P2X7 receptor and showing no immunodetection or immunoprecipitation with anti-EE primary antibodies (see supplemental Fig. 1, A and B).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Average results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. from the number of cells or assays indicated in the figure legends. Statistics were performed using SigmaStat 3.0.1a (Systat software). t tests were used to compare groups. Alternatively, when normality tests failed, Mann-Whitney Rank sum tests were used. Significances are given in figure legends.

RESULTS

Human and Rat P2X7R Current Facilitation upon Prolonged or Repeated ATP Applications

Prolonged applications of ATP (5 mm), applied for 110 s to HEK293 cells expressing human P2X7R, resulted in typical inward currents recorded at a −60-mV holding potential (Fig. 1A, red trace). These currents are characterized by initial rapid onsets called “instantaneous currents” of −182 ± 29 pA (n = 9 cells) and were then followed by an ∼9-fold increase in current amplitude at the end of the 110-s-long ATP application (−1,596 ± 261 pA, n = 9 cells). Human P2X7 receptors show a very slow facilitation that eventually reaches a maximum (see supplemental Fig. 1). This is sometimes seen with 110-s-long ATP applications, but most of the time it needs more than the 2-min agonist application to reach the steady-state current. As described previously (29–31), membrane blebbing occurs with sustained ATP application. These blebs often resulted in a pipette-membrane seal instability and loss of the patch. This usually prevents us from recording the maximal hP2X7 current. Therefore, a time for half-facilitation (F½) under this 110-s-long protocol was calculated giving an F½ of 65.5 ± 5.6 s (n = 9) for human P2X7R. However, the F½ calculated in this condition is certainly underestimating the real time for reaching half-facilitation. Protocols longer than 2 min are needed to reach the maximal steady-state current (−2,011 ± 581 pA, n = 3 cells), which is still significantly smaller than the fully facilitated rat P2X7 current.

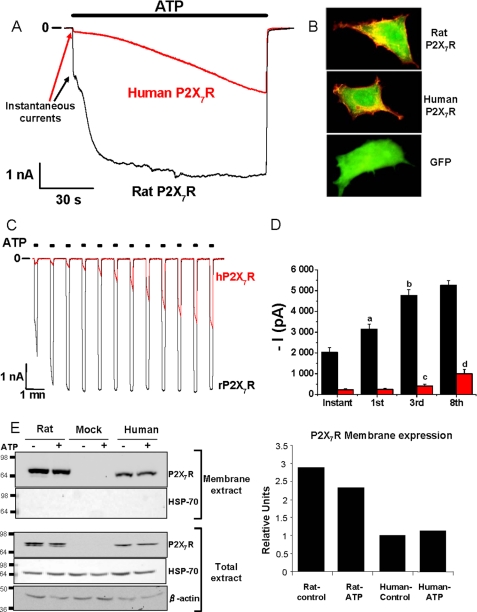

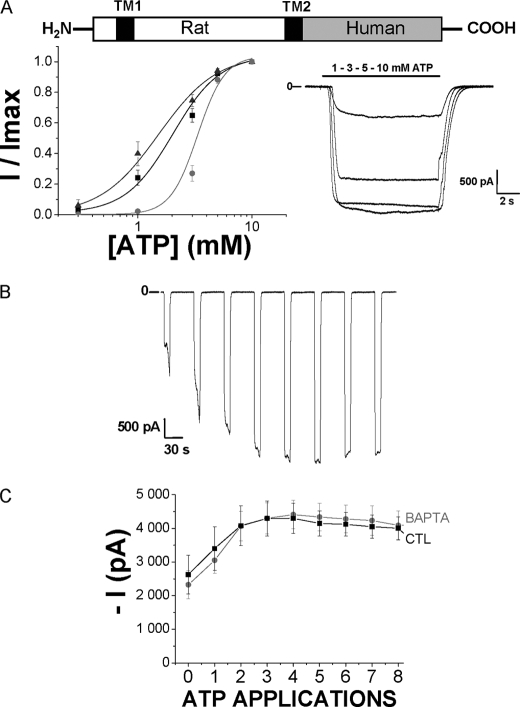

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of human and rat P2X7 facilitation. Human and rat P2X7Rs were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells. A, representative facilitating currents recorded from human (red trace) and rat (black trace) P2X7R during a 110-s-long application of 5 mm ATP. Initial instantaneous currents are shown by arrows for each trace. B, representative immunofluorescence staining experiments performed in HEK293 cells transiently transfected rat (upper panel) and human (middle panel) P2X7R (red staining, anti-rabbit IgG TRITC) and cotransfected with GFP (green staining) or only with GFP (lower panel). Only cells transfected with P2X7-EE-tagged receptors showed red staining. C, representative inward currents recorded from successive applications of 5 mm ATP (10 s duration) separated by 40-s intervals, from a holding potential of −60 mV, from human (red trace) and rat (black trace) P2X7R. D, mean currents (instantaneous, at the first, third, or eighth ATP application) obtained following the previous protocol from rat (black bars) and human (red bars) P2X7R. Statistical differences are as follows: column a, at p < 0.001 when comparing first to instantaneous currents to currents at the first ATP application in rat; column b, at p < 0.001 when comparing currents from third to first ATP application in rat; column c, at p < 0.05 when comparing currents from third to first ATP application in human; column d, at p = 0.002 when comparing currents from eighth to third ATP application in human. For all ATP applications, P2X7 currents from rat receptors were significantly (p < 0.001) bigger than those from human receptors. E, biotinylation experiments showing the surface expression of P2X7 receptors compared with the total protein expression in cell lysates after a 2-min stimulation with 5 mm ATP (+) or not (−) in HEK293 cells transfected with either rat or human EE-tagged receptors or nontransfected cells (Mock). Proteins were visualized using anti Glu-Glu primary antibody. HSP-70 was used as a negative control in the membrane extract (biotinylated) showing that the experiment was not biotinylating intracellular proteins. β-Actin was used as a control loading marker in each condition of the total extract. Numbers at the right of the figure indicate the molecular mass in kDa. This figure is representative of three independent experiments. Right is the quantification of plasma membrane P2X7R coming from the exposed biotinylation experiment, depending on species as a function of ATP stimulation or not.

As reported previously, rat P2X7R currents show a dramatic facilitation (24), and we wanted to compare with human receptors in terms of kinetics and current amplitudes. Prolonged applications of ATP (110 s, 5 mm) applied to HEK293 cells expressing human or rat P2X7R resulted in a important phenomenon of facilitation in both cases; however, kinetics for the current increases were very different (Fig. 1A, black trace). Although this phenomenon was slow to develop with human receptors, the facilitation process was very quick with rat P2X7R as follows: F½ was 13.4 ± 0.4 s (n = 7 cells). Currents from rat P2X7R also reached a maximal amplitude after ∼40 s of ATP application. Both instantaneous (−1,955 ± 56 pA, n = 7 cells) and maximal currents (−5,651 ± 352 pA, n = 7 cells) from rat P2X7R were statistically bigger than those recorded with human receptors after the same ATP application duration. Immunofluorescence assays were performed to verify the cellular distribution of either rat and human P2X7R in HEK293 cells co-transfected with GFP (Fig. 1B). These experiments showed that rat and human receptors are mainly expressed to the plasma membrane even in the absence of agonist stimulation.

Although the rat P2X7R showed much bigger instantaneous and maximal currents than the human ortholog, there was no difference concerning the initial addressing and the intensity of P2X7R labeling at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B). This suggests a difference in receptor activation.

Because the initial electrophysiological protocol did not allow an easy quantification for the facilitation process and also resulted in membrane blebbing (24, 29), interfering with the membrane seal, we quantified ATP-mediated facilitation with the protocol illustrated in Fig. 1C. Repeated 10-s applications of ATP (5 mm), applied at 40-s intervals to HEK293 cells expressing either rat or human P2X7R, resulted in typical inward currents at a −60-mV holding potential, characteristic of rapid but reversible (at the agonist disappearance) channel opening (Fig. 1C). In both species, repeated stimulations of P2X7R with the agonist resulted in an important increase of current amplitudes, with the same kinetics observed in Fig. 1A. Here again, profiles of ATP-evoked currents were strictly different depending on the species; the instantaneous current, termed hereafter as 0, was ∼10 times bigger for rat than for human P2X7R as follows: −2,036 ± 214 pA (n = 41 cells) versus −230 ± 45 pA (n = 23 cells), respectively (Fig. 1, C and D). For all ATP applications, currents obtained from human P2X7R were significantly smaller than those recorded from rat receptors.

Following the facilitation process, rat P2X7 currents reached a maximum amplitude at the third application, whereas human P2X7 currents were only significantly bigger after the third application and were still increasing after the eighth ATP application (Fig. 1, C and D). After eight ATP applications, the mean P2X7 current recorded was −5,259 ± 229 pA (n = 36 cells) for the rat and −849 ± 184 pA (n = 22 cells) for the human receptor (Fig. 1D and Table 1). We asked if these differences in the instantaneous current amplitudes and facilitation phenomena could be due to a lower expression level of the human P2X7 receptor and if ATP treatment could increase plasma membrane addressing of receptors to the membrane. We therefore performed biotinylation experiments on cells expressing either rat or human P2X7R, after 2 min of stimulation with 5 mm extracellular ATP or not, and quantified P2X7R proteins at the membrane (Fig. 1E). We showed that both receptor orthologs are highly expressed at the membrane, but there was a significantly higher quantity of rat compared with human P2X7 proteins at the membrane. This could be partially responsible for the bigger instantaneous current. However, ATP stimulation was not responsible for an increase of rat or human receptors addressing the plasma membrane.

TABLE 1.

EC50 values and currents amplitudes for P2X7R constructs used in this study

EC50 values and current amplitudes for P2X7R constructs used in this study and expressed in HEK293 cells are given. I0 and I8 indicate instantaneous currents and currents recorded at the 8th ATP application, respectively. I8/I0 represent ratios calculated from currents recorded at the 8th application of ATP and instantaneous currents before facilitation. Results are expressed as means ± S.E. Numbers in parentheses indicate total number of experiments. Statistical differences are as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001 when compared with rat P2X7R; and +, p < 0.05 and +++, p < 0.001 when compared with human P2X7R.

| Constructs | ATP EC50 | Current amplitudes |

I8/I0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I0 | I8 | |||

| mm | pA | |||

| Human P2X7 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | −230 ± 45 | −849 ± 184 | 5.7 ± 1.5 |

| (16) | (23) | (22) | (22) | |

| Rat P2X7 | 2.02 ± 0.18 | −2,036 ± 214 | −5,259 ± 229 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| (17) | (41) | (36) | (36) | |

| Human with rat C-terminal P2X7 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | −760 ± 82+++ | −1,905 ± 230+++ | 2.6 ± 0.2+ |

| (7) | (15) | (15) | (15) | |

| Rat with human C-terminal P2X7 | 1.50 ± 0.30 | −2,628 ± 580 | −4,003 ± 337** | 2.7 ± 0.9* |

| (7) | (10) | (10) | (10) | |

| Human P2X7 Ile-541, Ser-552, and Val-559 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | −589 ± 78+++ | −2,277 ± 219+++ | 4.6 ± 0.4 |

| (16) | (31) | (30) | (30) | |

| Rat D cysteine-rich domain | 0.91 ± 0.10 | −2,224 ± 309 | −1,772 ± 275*** | 0.8 ± 0.1*** |

| (6–14) | (14) | (14) | (14) | |

This experiment was confirmed by supplemental Fig. 2, which represents Western blots coming from different protein fractions (total cell lysate; cytosolic and endomembrane fraction; and plasma membrane fraction) extracted from HEK293 cells transfected with either human or rat P2X7R. Total cell lysate contained P2X7R, β-actin, and adaptin-β. The cytosolic/endomembrane-enriched fraction was characterized by the presence of soluble β-actin and adaptin-β, which is mainly found in endomembranes. The plasma membrane-enriched fraction was the fraction containing the most of both rat and human P2X7R, although the immunoblot of β-actin and adaptin-β was weak. This indicated that the majority of P2X7 proteins is translocated to plasma membrane. Although the total amount of P2X7 proteins were similar for rat and human receptors in total cell lysates (supplemental Figs. 2 and Fig. 3B), there was a significantly higher quantity of rat compared with human P2X7 proteins at the membrane (by 1.80 ± 0.10-fold). Stimulating the cells with 5 mm ATP, which increases both human and rat P2X7-related currents and increases internal Ca2+ concentration (supplemental Fig. 3C), did not induce an increase of plasma membrane proteins (supplemental Fig. 2).

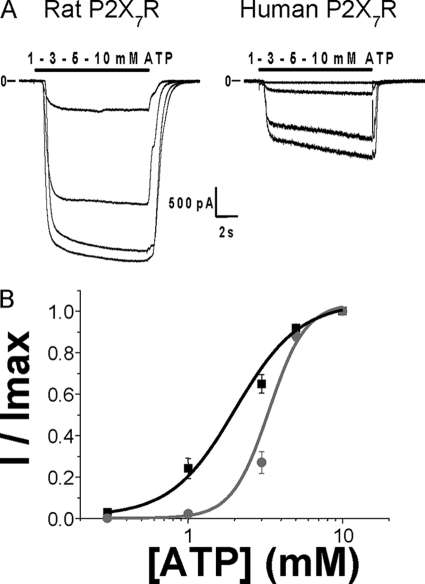

Taken together, these results indicate that the facilitation phenomenon for both P2X7R orthologs seems not to be due to an increase of the receptor addressing the plasma membrane but rather to a receptor property. We therefore assessed the effect of facilitation on receptor properties. ATP concentration-response curves were determined after full current facilitation. As reported previously, rat P2X7R are more sensitive to ATP than their human orthologs (3, 17), and the EC50 values were 2.02 ± 0.18 mm (n = 17 cells) and 3.3 ± 0.1 mm (n = 16 cells), respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of ATP dose-responses curves from human and rat P2X7R. A, representative currents from P2X7-transfected HEK293 cells, in response to 10-s-long applications of increasing concentrations of ATP (0.3, 1; 3, 5, and 10 mm), for rat (left) and human (right) P2X7R. B, ATP concentration-response curves for human (gray circles) and rat (black squares) P2X7 currents after full facilitation. Currents were relativized to the maximal effect obtained with 10 mm ATP. ATP EC50 values are, respectively, 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for human P2X7 (gray circles, n = 16 cells) and 2.02 ± 0.18 mm for rat P2X7 (black squares, n = 17 cells).

C-terminal Tail Differentially Regulates Human and Rat P2X7R Facilitation

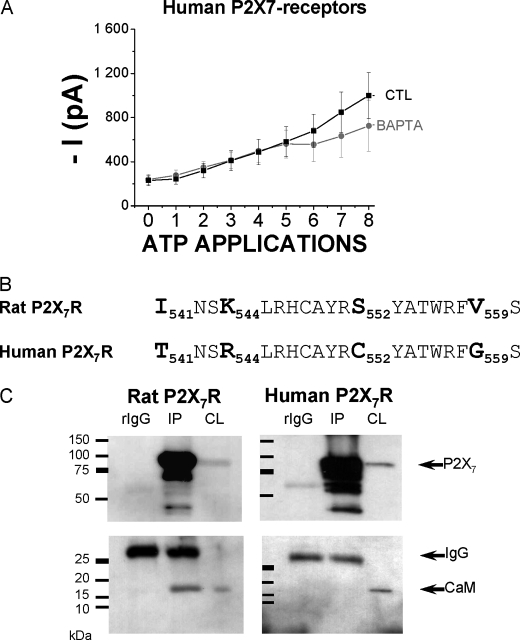

We recently showed that rat P2X7R facilitation is made of both Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent and Ca2+-independent components (24). The Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent component can be inhibited by chelating intracellular calcium with 5 mm BAPTA. Therefore, when BAPTA was brought into the patch pipette, both instantaneous and sustained rat P2X7 currents were decreased by 60–80% (24). Here, because of the apparent differences in human P2X7 current facilitation, we asked if facilitations on human and rat P2X7R were following the same mechanisms. We found that BAPTA (5 mm) into the intracellular solution had no effect on the human P2X7 current densities and no effect on the facilitation process (Fig. 3A). We recently identified a new 1-5-16 Ca2+-dependent CaM-binding motif in the rat P2X7 C-terminal end, between Ile-541 and Ser-560 (24), and because our results show an absence of Ca2+-dependent facilitation in human receptors, we asked if human receptors had the same motif. Fig. 3B shows the four amino acid differences between human and rat P2X7 sequences at the putative calmodulin-binding motif (I541T, K544R, S552C, and V559G). This human sequence did not correspond to a calmodulin-binding site according to bioinformatic tools (calmodulin target database, University of Toronto, Canada). Therefore, we asked whether co-immunoprecipitation experiments would further support this finding or if there may exist a Ca2+-independent CaM-binding site (such as “IQ” motifs) on human receptors. CaM was previously demonstrated to physically interact with rat P2X7R (24). In this previous study, we showed that CaM constitutively interacts with rat P2X7R at basal intracellular calcium concentrations and that this interaction is dynamically increased by about 1.5-fold after stimulating the cells 45 s with ATP (24). We reproduced the same protocol, and here again CaM clearly associates with the rat receptor, although no CaM was immunodetected in human P2X7R immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3C), but despite that similar amounts of intracellular Ca2+ were found after 45–50 s of ATP stimulation of rat or human P2X7 receptors (supplemental Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 3.

Regulations of rat and human ATP-evoked P2X7 current facilitation by the internal Ca2+ and calmodulin. A, ATP-evoked human P2X7 current facilitation (5 mm ATP, 10 s duration, and 40-s intervals) was studied using two internal solutions having different Ca2+ activities by the use of Ca2+ chelators (see “Experimental Procedures”). CTL (n = 23 cells) represents the control internal solution having 10 mm EGTA and BAPTA (n = 8 cells) having 5 mm BAPTA. 0 indicates the instantaneous current amplitude before facilitation, and 1 indicates the maximal current obtained from this first ATP application. Results are expressed as means ± S.E. B, identification of a putative calmodulin-binding site in the intracellular C terminus of the rat P2X7R (thanks to the calmodulin target database). Below is represented the corresponding sequence found in human P2X7R, which is not described as potentially binding calmodulin. The differing residues are represented in boldface. C, P2X7 receptors were detected (anti-EE antibody, 1:2,000 dilution) in cell lysates (CL) and after P2X7 receptors Glu-Glu-tagged IP with an anti-EE polyclonal antibody. Anti-rabbit immunoglobin (rIgG) was used as a negative control to rule out nonspecific binding. Calmodulin was detected by a monoclonal anti-calmodulin antibody (1:1,000 dilution) in cell lysates and co-immunoprecipitates with the rat but not with human P2X7R. Co-immunoprecipitations shown here are representative of four independent experiments in each case.

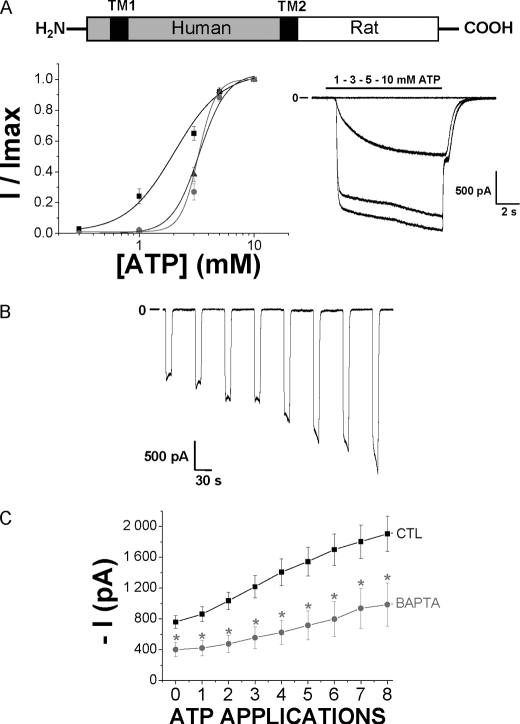

To study the effects of the species-specific C-terminal ends on P2X7R facilitation, we examined chimeric human receptors with the rat C terminus. These receptors present the human P2X7R sequence from the first amino acid to the residue Gly-345 in TM2 and the rat P2X7 C-terminal extremity from Leu-346 to Tyr-595 (see diagram in Fig. 4A). These chimeric receptors were expressed in HEK293 cells and then studied for their ATP sensitivity and facilitation process. The ATP EC50 was 3.3 ± 0.1 mm (Fig. 4A and Table 1) and therefore similar to human WT receptors. Overall kinetics for current facilitation were similar to those observed with the WT human receptor; however, current amplitudes were bigger than with the WT human receptor (Fig. 4B and Table 1), and intracellular BAPTA significantly reduced both instantaneous and sustained inward currents of this chimeric receptor (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Study of the chimeric human P2X7 receptor having rat P2X7 C-terminal extremity. A, schematic representation of the chimeric receptor displaying the human P2X7 receptor body from the first residue to the Gly-345 in TM2 and the Rat P2X7 C-terminal extremity from Leu-346 to Tyr-595. Transmembrane segments are represented by black squares. Below, on the left are shown ATP concentration-response curves from human (gray circles), rat (black squares), and the human-rat chimeric (dark gray triangles) P2X7R. Currents were relativized to the maximal effect obtained with 10 mm ATP. ATP EC50 values are, respectively, 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for human (n = 16 cells), 2.02 ± 0.18 mm for rat (n = 17 cells), and 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for chimeric human-rat (n = 7 cells) P2X7R. On the right are shown representative currents from chimeric human-rat P2X7R transfected in HEK293 cells, in response to 10-s-long applications of increasing concentrations of ATP (0.3, 1, 3, 5, and 10 mm). B, representative inward currents recorded from successive applications of 5 mm ATP (10 s duration) separated by 40-s intervals, from a holding potential of −60 mV, from chimeric human-rat P2X7R. C, ATP-evoked chimeric human-rat P2X7 current facilitation (5 mm ATP, 10-s duration, 40-s intervals) was studied using two internal solutions: CTL (n = 15 cells) and BAPTA (n = 10 cells). *, statistically different at p < 0.05.

The complementary rat-human chimeric receptor expressed in HEK293 cells was then studied. These rat P2X7R chimera having the human C-terminal tail from residue Ala-347 in TM2 (see diagram in Fig. 5A) gave classical ATP-evoked inward currents. The ATP EC50 for this chimera was 1.5 ± 0.3 mm (Fig. 5A and Table 1) and therefore closer to the rat than to the human WT receptors. This rat-human chimeric receptor showed a fast current facilitation, which rapidly reached a maximum after four 10-s-long 5 mm ATP applications (Fig. 5B). However, chelating intracellular calcium by introducing 5 mm BAPTA into the patch pipette did not reduce current density or facilitation (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 5.

Study of the chimeric rat P2X7 receptor having human P2X7 C-terminal extremity. A, schematic representation of the chimeric receptor displaying the rat P2X7 receptor body from the first residue to the Ala-347 in TM2 and the human P2X7 C-terminal extremity from Ala-348 to Tyr-595. Transmembrane segments are represented by black squares. Below, on the left are shown ATP concentration-response curves from human (gray circles), rat (black squares), and the rat-human chimeric (dark gray triangles) P2X7R. Currents were relativized to the maximal effect obtained with 10 mm ATP. ATP EC50 values are, respectively, 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for human (n = 16 cells), 2.02 ± 0.18 mm for rat (n = 17 cells), and 1.5 ± 0.3 mm for chimeric rat-human (n = 7 cells) P2X7R. On the right are shown representative currents from chimeric rat-human P2X7R transfected in HEK293 cells, in response to 10-s-long applications of increasing concentrations of ATP (0.3, 1, 3, 5, and 10 mm). B, representative inward currents recorded from successive applications of 5 mm ATP (10 s duration) separated by 40-s intervals, from a holding potential of −60 mV, from chimeric rat-human P2X7R. C, ATP-evoked chimeric rat-human P2X7 current facilitation (5 mm ATP, 10 s duration, 40-s intervals) was studied using two internal solutions, CTL (n = 10 cells) and BAPTA (n = 8 cells).

Calmodulin Regulates Ca2+-dependent Facilitation

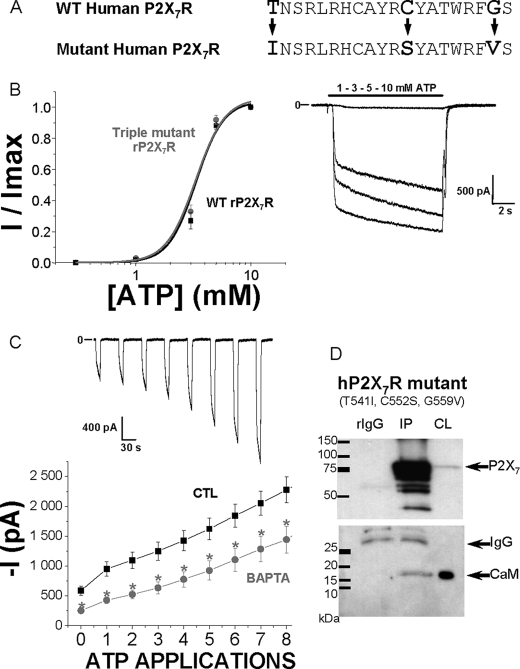

To assess if the 1-5-16 calmodulin-binding motif in the rat P2X7R was the only determinant from the C-terminal end of rat receptors needed to enhance the Ca2+-dependent facilitation, we substituted three amino acids in the human P2X7R sequence. The amino acids substituted were T541I, C552S, and G559V, and their substitution did not interfere with other parts of the C-terminal end (Fig. 6A). These amino acids were chosen to create a motif similar to the one observed in rat P2X7R and to potentially make a putative calmodulin-binding site in the human receptor C-terminal tail. The appearance of such a motif was checked by analyzing the new sequence with the calmodulin target database, which gave a maximal predicted calmodulin binding score for this region. The triple mutant human P2X7R was then expressed in HEK293 cells. Its ATP EC50 was 3.3 ± 0.1 mm (Fig. 6B and Table 1) and therefore identical to what is observed with human WT receptors (Fig. 3A). Current facilitation was then studied (Fig. 6C), and the use of 5 mm BAPTA into the patch pipette revealed a calcium-dependent component for current facilitation that was absent in WT human P2X7 receptors (Fig. 3A). Both instantaneous and sustained inward currents recorded upon stimulation of these triple mutant were bigger than those of WT human P2X7R (Fig. 6C and Table 1). CaM was previously demonstrated to physically interact with rat P2X7R and to be responsible for the calcium-dependent current facilitation (24). Although CaM did not associate with WT (Fig. 3B), a CaM-receptor interaction was found using the triple (T541I, C552S, and G559V) human P2X7R mutant (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

Introduction of a putative calmodulin-binding site on human P2X7 receptor. A, site-directed mutations of three residues performed on the WT and human P2X7R (T541I, C552S, and G559V) to create a putative calmodulin-binding site. B, on the left are represented ATP concentration-response curves from the WT (black squares) and from the triple mutant (gray circles) human P2X7R. Currents were relativized to the maximal effect obtained with 10 mm ATP. ATP EC50 values are, respectively, 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for WT (n = 16 cells) and 3.3 ± 0.1 mm for triple mutant (n = 10 cells) human P2X7R. On the right are shown representative currents from the triple mutant human P2X7R transfected in HEK293 cells, in response to 10-s-long applications of increasing concentrations of ATP (0.3, 1, 3, 5, and 10 mm). C, representative inward currents recorded from successive applications of 5 mm ATP (10 s duration) separated by 40-s intervals, from a holding potential of −60 mV, from triple mutant human P2X7R. Lower panel is the ATP-evoked triple mutant human P2X7 current facilitation (5 mm ATP, 10 s duration, 40-s intervals), which was studied using two internal solutions, CTL (n = 31 cells) and BAPTA (n = 27 cells). *, statistically different at p < 0.05. D, calmodulin was detected by a monoclonal anti-calmodulin antibody (1:1,000 dilution) in cell lysates and co-immunoprecipitates with the mutated human P2X7 receptors (T541I, C552S, and G559V). Co-immunoprecipitations shown here are representative of four independent experiments.

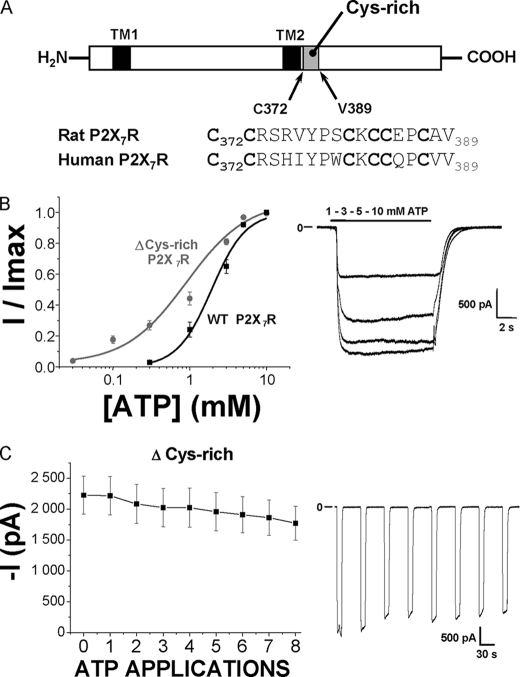

Involvement of the Cys-rich Domain in Mechanics of P2X7R Facilitation

We then tried to increase our understanding of the receptor mechanics for the facilitation phenomenon. Therefore, we looked for particular motifs in the P2X7R sequence found either in human or rat receptors and that could be involved in the conformational changes occurring during facilitation. P2X7Rs contain an 18-amino acid segment rich in six cysteine residues (Cys-rich motif) immediately after TM2 (Fig. 7A). This sequence is not found in the other P2X receptors and is highly conserved between P2X7R orthologs, and this might suggest that it contributes to properties specific to P2X7R such as the Ca2+-independent facilitation. We therefore studied the rat P2X7R in which this segment has been deleted (ΔCys-rich). As already reported, the ATP concentration-response curve for the ΔCys-rich mutant was ∼2-fold shifted to the left, and current deactivation was slower than the WT rat receptor (Fig. 7C and Table 1) (28). Although instantaneous currents were not different from those recorded with WT receptors, the ΔCys-rich P2X7R mutant showed no facilitation at all (Fig. 7C and Table 1).

FIGURE 7.

Study of the rat P2X7 receptor with deleted cysteine-rich (Cys-372 to Val-389) domain in the cytosolic C terminus. A, schematic representation to show the localization of the cysteine-rich domain (Cys-rich) deleted in this mutant receptor. Transmembrane segments are represented by black squares. B, on the left are shown ATP concentration-response curves for WT (black squares) and the ΔCys-rich mutant (dark gray triangles) rP2X7R. Currents were relativized to the maximal effect obtained with 10 mm ATP. ATP EC50 values are, respectively, 2.02 ± 0.18 mm for WT (n = 17 cells) and 0.9 ± 0.1 mm for ΔCys-rich mutant (n = 6–14 cells) rP2X7R. On the right are shown representative currents from ΔCys-rich mutant rP2X7R transfected in HEK293 cells, in response to 10-s-long applications of increasing concentrations of ATP (1, 3, 5, and 10 mm). C, mean ATP-evoked ΔCys-rich mutant P2X7 currents for multiple ATP applications (5 mm ATP, 10 s duration, 40-s intervals) showing no facilitation (n = 14 cells). On the left are representative inward currents recorded from successive applications of 5 mm ATP (10 s duration) separated by 40-s intervals, from a holding potential of −60 mV, from ΔCys-rich mutant rP2X7R.

DISCUSSION

P2X7Rs are ATP-gated receptors involved in many physiological processes (bone remodeling, salivary secretion, etc.) with a central role in immunity and showing specific biophysical properties (1, 4). One of these was the fascinating phenomenon of facilitation by which agonist sensitivity and currents generated by P2X7R both increase upon repeated or sustained agonist application, leading to the hypersensitivity of the receptor and to the potentiation of their downstream signaling pathways. P2X7Rs show no desensitization, and the hypothesis by which they could be considered as “danger sensor” (4, 10), monitoring high levels of extracellular ATP released by stressed or dead cells, goes along with this unique biophysical property of facilitation.

Although P2X7R orthologs have been shown to display several pharmacological and biophysical differences (1, 26, 27, 32), most of the studies were performed to date on rat receptors. Therefore, it is of high importance to focus on human receptors and characterize their functional properties to completely understand their roles in human physiological or pathological processes. Improving the knowledge about their structure-function relationship will also help in the development of new pharmacological modulators for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases.

This study shows that the facilitation phenomenon recorded in cells expressing either rat or human P2X7Rs is not due to an increase of receptors addressing the plasma membrane under agonist stimulation but rather to the biophysical properties of the receptors. Furthermore, using both functional and biochemical techniques, it shows that human P2X7Rs have a much slower facilitation than rat orthologs due to the absence of a CaM-binding site in the C-terminal end.

Calmodulin is a ubiquitous calcium sensor known to interact with both calcium-independent (such as “IQ motif”) and calcium-dependent motifs (such as “1–10,” “1–14,” or “1–16” motifs) thus regulating the activity of numerous proteins among which are ion channels. Usually, CaM prevents calcium overload in cells by inactivating voltage-gated calcium (33) or transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (34–36) or by activating calcium-dependent potassium channels (37). However, we have recently demonstrated that Ca2+-dependent CaM binding to the rat P2X7 receptor induces a dramatic current facilitation, consequently increasing calcium entry (24). This property is responsible for a hypersensitization of P2X7 receptors and induces a smaller delay as well as a bigger intensity of the physiological responses associated with their activation. This particular behavior of rat P2X7R will have to be confirmed in native cells and should be correlated to physiological processes linked to P2X7R activation such as interleukin 1β release.

The work exposed herein focuses on the characterization of the human P2X7R concerning the still poorly known facilitation process. Here, we show that the CaM-P2X7R interaction observed in rat does not exist in human receptors, and this is responsible for a slower facilitation and a smaller current density. This functional difference is due to three amino acid changes in the C-terminal tail of human receptors. We also delineated that the substitution of only these three key residues in the human P2X7 C-terminal tail (T541I, C552S, and G559V) is sufficient to allow CaM binding and Ca2+-dependent facilitation. In consequence, the human receptor presents a smaller current facilitation than the one for rat P2X7R, due to a Ca2+-independent process that has not been elucidated up to now.

We previously showed that this current facilitation with repeated or prolonged agonist applications was also correlated to an increase in the agonist sensitivity (24). In this study we have introduced a Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent component to the facilitation of human receptors by adding the C terminus of rat receptor (chimeric receptor in Fig. 4) or by creating a CaM-binding motif in the human C terminus (triple mutant receptor in Fig. 6). However, although current densities were increased in both cases, dose-response curves for ATP in these two mutated receptors were not modified in comparison with WT human P2X7R (Table 1). Therefore, the presence of the Ca2+-CaM-binding motif is only responsible for the increased current density occurring during facilitation and cannot be held responsible for this increased sensitivity to ATP. Indeed, ATP binding and activation kinetics of the receptor are not determined by the calmodulin-binding site or the C terminus. However, we can speculate that the increase in agonist sensitivity is correlated to the Ca2+-independent facilitation process.

The molecular process responsible for this current facilitation is still unknown. It seems that ATP does not induce an increase of receptors trafficking to the membrane. It can be proposed that binding of Ca2+-CaM to the C-terminal motif could increase the single channel conductance. This should be further examined. Similarly to what has been recently done with the zebrafish P2X4 receptor (38), the crystal structure of the complete P2X7R would largely increase the knowledge on its functioning.

The activity of the P2X7 receptor is often evaluated by its ability to induce, upon prolonged agonist exposure, membrane permeabilization to cationic fluorescent dyes under 1 kDa such as ethidium or YO-PRO1 (1). Interestingly, a previous study already showed that the truncation of the C-terminal end of rat P2X7R, bearing the calmodulin-calcium-binding motif, dramatically reduced YO-PRO uptake compared with WT rat P2X7R (17). Moreover, it is also shown in the same study that human chimeric receptors with the rat C terminus were responsible for a significant increase of YO-PRO uptake compared with WT human P2X7R (17). This indicates the importance of the C-terminal tail in rat P2X7R functionality, and this is clearly in line with the results obtained herein. However, Ca2+-CaM-dependent facilitation in rat P2X7R was not involved in cell permeabilization and the formation of the large pore, measured by ethidium uptake into the cell, because it was the same from the WT or CaM binding region mutant rat P2X7R (24).

By studying P2X7 chimeric receptors, we also found that the Ca2+-independent facilitation process is conserved independently of the C terminus. Therefore, we postulate that it could rely on other parts of the receptor that might be partly conserved between human and rat receptors (28). A juxtamembrane cytosolic 18-amino acid domain rich in cysteines is highly conserved among species. By deleting this cysteine-rich domain, we found that this part is critical for general P2X7R facilitation (both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent) and might represent a hinge region for receptor conformational changes occurring during facilitation. Interestingly, this particular region has been shown to be involved in receptor permeability to N-methyl-d-glucamine but not in dye uptake (28). Therefore, receptor facilitation could be responsible for or concomitant to the increased permeability to N-methyl-d-glucamine upon maintained agonist application.

From these results, we cannot exclude that the Ca2+-independent facilitation process might bring into play some other receptor parts such as the extracellular loop and transmembrane domains, which are already responsible for agonist binding and receptor gating. Further studies will be needed to completely understand the Ca2+-independent facilitation process of P2X7R. This could be done by studying conserved motifs among orthologs.

P2X7R plays crucial roles in immune cells initiating and maintaining the inflammatory process through the release of cytokines from the interleukin-1 family; therefore, our data support important physiological and pathological differences depending on species, in terms of time and intensity that could be of importance in the case of the immune/inflammatory response to pathogens. With the expansion of transgenic animals during the last decades, all these differences must be taken into account when studying immunological responses in animal models. Also, an increasing number of polymorphisms and mutations are found in the human P2X7 sequence and are described as highly interfering with the receptor function (from complete loss-of-function to gain-of-function) and affecting the immune response (39–43). Genetic studies linked nonsynonymous polymorphisms into the P2X7R gene to different pathologies, including major depressive disorder (44), bipolar disorder (45), anxiety disorder (46, 47), chronic lymphatic leukemia (48, 49), extrapulmonary tuberculosis (50), and thyroid cancer (51). Therefore, we need to increase the knowledge of P2X7 receptor residues and domains involved in the regulation of its biophysical properties, leading basic studies to have a great physio/pathological importance. This study brings some new elements on the understanding of the still poorly characterized structure-function relationships of P2X7R.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Martin, Weihong Ma, and Mari Carmen Baños for support with cell culture.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the “Partenariat Hubert Curien-Alliance” from the French Foreign and European Ministry and the French Embassy in the United Kingdom, and Isciii Grants EMER07/049 (to A. B.-M.) and PFIS0009/120 (to P. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- P2X7R

- P2X7 receptor

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- CaM

- calmodulin

- WT

- wild type

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- CTL

- control intracellular solution

- BAPTA

- 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- TM

- transmembrane

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- PSS

- physiological saline solution.

REFERENCES

- 1.North R. A. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82, 1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnstock G. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 659–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surprenant A., Rassendren F., Kawashima E., North R. A., Buell G. (1996) Science 272, 735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surprenant A., North R. A. (2009) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 333–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collo G., Neidhart S., Kawashima E., Kosco-Vilbois M., North R. A., Buell G. (1997) Neuropharmacology 36, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari D., Villalba M., Chiozzi P., Falzoni S., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Di Virgilio F. (1996) J. Immunol. 156, 1531–1539 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sim J. A., Young M. T., Sung H. Y., North R. A., Surprenant A. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 6307–6314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X. F., Han P., Faltynek C. R., Jarvis M. F., Shieh C. C. (2005) Brain Res. 1052, 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari D., Pizzirani C., Adinolfi E., Lemoli R. M., Curti A., Idzko M., Panther E., Di Virgilio F. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 3877–3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Virgilio F. (2007) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chessell I. P., Hatcher J. P., Bountra C., Michel A. D., Hughes J. P., Green P., Egerton J., Murfin M., Richardson J., Peck W. L., Grahames C. B., Casula M. A., Yiangou Y., Birch R., Anand P., Buell G. N. (2005) Pain 114, 386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labasi J. M., Petrushova N., Donovan C., McCurdy S., Lira P., Payette M. M., Brissette W., Wicks J. R., Audoly L., Gabel C. A. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 6436–6445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcaraz L., Baxter A., Bent J., Bowers K., Braddock M., Cladingboel D., Donald D., Fagura M., Furber M., Laurent C., Lawson M., Mortimore M., McCormick M., Roberts N., Robertson M. (2003) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 4043–4046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stokes L., Jiang L. H., Alcaraz L., Bent J., Bowers K., Fagura M., Furber M., Mortimore M., Lawson M., Theaker J., Laurent C., Braddock M., Surprenant A. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 149, 880–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson D. W., Gregg R. J., Kort M. E., Perez-Medrano A., Voight E. A., Wang Y., Grayson G., Namovic M. T., Donnelly-Roberts D. L., Niforatos W., Honore P., Jarvis M. F., Faltynek C. R., Carroll W. A. (2006) J. Med. Chem. 49, 3659–3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romagnoli R., Baraldi P. G., Cruz-Lopez O., Lopez-Cara C., Preti D., Borea P. A., Gessi S. (2008) Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 12, 647–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rassendren F., Buell G. N., Virginio C., Collo G., North R. A., Surprenant A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5482–5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 5071–5082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M., Jiang L. H., Wilson H. L., North R. A., Surprenant A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6347–6358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson H. L., Wilson S. A., Surprenant A., North R. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34017–34023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smart M. L., Gu B., Panchal R. G., Wiley J., Cromer B., Williams D. A., Petrou S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8853–8860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denlinger L. C., Sommer J. A., Parker K., Gudipaty L., Fisette P. L., Watters J. W., Proctor R. A., Dubyak G. R., Bertics P. J. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 1304–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker D., Woltersdorf R., Boldt W., Schmitz S., Braam U., Schmalzing G., Markwardt F. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25725–25734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roger S., Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 6393–6401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young M. T., Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys B. D., Virginio C., Surprenant A., Rice J., Dubyak G. R. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibell A. D., Kidd E. J., Chessell I. P., Humphrey P. P., Michel A. D. (2000) Br. J. Pharmacol. 130, 167–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang L. H., Rassendren F., Mackenzie A., Zhang Y. H., Surprenant A., North R. A. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289, C1295–C1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackenzie A. B., Young M. T., Adinolfi E., Surprenant A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33968–33976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adinolfi E., Callegari M. G., Ferrari D., Bolognesi C., Minelli M., Wieckowski M. R., Pinton P., Rizzuto R., Di Virgilio F. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3260–3272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhoef P. A., Estacion M., Schilling W., Dubyak G. R. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 5728–5738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young M. T., Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 149, 261–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halling D. B., Aracena-Parks P., Hamilton S. L. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006, er1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derler I., Hofbauer M., Kahr H., Fritsch R., Muik M., Kepplinger K., Hack M. E., Moritz S., Schindl R., Groschner K., Romanin C. (2006) J. Physiol. 577, 31–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu M. X. (2005) Pflugers Arch. 451, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiselyov K., Kim J. Y., Zeng W., Muallem S. (2005) Pflugers Arch. 451, 116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maylie J., Bond C. T., Herson P. S., Lee W. S., Adelman J. P. (2004) J. Physiol. 554, 255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawate T., Michel J. C., Birdsong W. T., Gouaux E. (2009) Nature 460, 592–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shemon A. N., Sluyter R., Fernando S. L., Clarke A. L., Dao-Ung L. P., Skarratt K. K., Saunders B. M., Tan K. S., Gu B. J., Fuller S. J., Britton W. J., Petrou S., Wiley J. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2079–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabrini G., Falzoni S., Forchap S. L., Pellegatti P., Balboni A., Agostini P., Cuneo A., Castoldi G., Baricordi O. R., Di Virgilio F. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denlinger L. C., Angelini G., Schell K., Green D. N., Guadarrama A. G., Prabhu U., Coursin D. B., Bertics P. J., Hogan K. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 4424–4431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sluyter R., Dalitz J. G., Wiley J. S. (2004) Genes Immun. 5, 588–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders B. M., Fernando S. L., Sluyter R., Britton W. J., Wiley J. S. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 5442–5446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucae S., Salyakina D., Barden N., Harvey M., Gagné B., Labbé M., Binder E. B., Uhr M., Paez-Pereda M., Sillaber I., Ising M., Brückl T., Lieb R., Holsboer F., Müller-Myhsok B. (2006) Hum. Mol. Genet 15, 2438–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barden N., Harvey M., Gagné B., Shink E., Tremblay M., Raymond C., Labbé M., Villeneuve A., Rochette D., Bordeleau L., Stadler H., Holsboer F., Müller-Myhsok B. (2006) Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 141B, 374–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erhardt A., Lucae S., Unschuld P. G., Ising M., Kern N., Salyakina D., Lieb R., Uhr M., Binder E. B., Keck M. E., Müller-Myhsok B., Holsboer F. (2007) J. Affect. Disord. 101, 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roger S., Mei Z. Z., Baldwin J. M., Dong L., Bradley H., Baldwin S. A., Surprenant A., Jiang L. H. (2010) J. Psychiatr. Res. 44, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiley J. S., Dao-Ung L. P., Gu B. J., Sluyter R., Shemon A. N., Li C., Taper J., Gallo J., Manoharan A. (2002) Lancet 359, 1114–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thunberg U., Tobin G., Johnson A., Söderberg O., Padyukov L., Hultdin M., Klareskog L., Enblad G., Sundström C., Roos G., Rosenquist R. (2002) Lancet 360, 1935–1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernando S. L., Saunders B. M., Sluyter R., Skarratt K. K., Goldberg H., Marks G. B., Wiley J. S., Britton W. J. (2007) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dardano A., Falzoni S., Caraccio N., Polini A., Tognini S., Solini A., Berti P., Di Virgilio F., Monzani F. (2009) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 695–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.