Abstract

Cdc34 is an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that functions in conjunction with SCF (Skp1·Cullin 1·F-box) E3 ubiquitin ligase to catalyze covalent attachment of polyubiquitin chains to a target protein. Here we identified direct interactions between the human Cdc34 C terminus and ubiquitin using NMR chemical shift perturbation assays. The ubiquitin binding activity was mapped to two separate Cdc34 C-terminal motifs (UBS1 and UBS2) that comprise residues 206–215 and 216–225, respectively. UBS1 and UBS2 bind to ubiquitin in the proximity of ubiquitin Lys48 and C-terminal tail, both of which are key sites for conjugation. When bound to ubiquitin in one orientation, the Cdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206, Tyr207, Tyr210, and Tyr211) are probably positioned in the vicinity of ubiquitin C-terminal residue Val70. Replacement of UBS1 aromatic residues by glycine or of ubiquitin Val70 by alanine decreased UBS1-ubiquitin affinity interactions. UBS1 appeared to support the function of Cdc34 in vivo because human Cdc34(1–215) but not Cdc34(1–200) was able to complement the growth defect by yeast Cdc34 mutant strain. Finally, reconstituted IκBα ubiquitination analysis revealed a role for each adjacent pair of UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206/Tyr207, Tyr210/Tyr211) in conjugation, with Tyr210 exhibiting the most pronounced catalytic function. Intriguingly, Cdc34 Tyr210 was required for the transfer of the donor ubiquitin to a receptor lysine on either IκBα or a ubiquitin in a manner that depended on the neddylated RING sub-complex of the SCF. Taken together, our results identified a new ubiquitin binding activity within the human Cdc34 C terminus that contributes to SCF-dependent ubiquitination.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, NMR, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (Ubc), Ubiquitination, Cdc34

Introduction

Ubiquitination is a complex protein modification reaction that produces a covalent isopeptide bond linking the ubiquitin Gly76 carboxyl end to the ϵ-amino group of a lysine residue within a substrate protein (1). One of the hallmarks of this modification is that substrates are frequently attached with polyubiquitin chains, formed by isopeptide linkage joining the ubiquitin Gly76 carboxyl end and one of its seven internal lysine residues. Three enzymatic activities typically participate in the ubiquitination reaction, including a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) that forms an E1-S∼ubiquitin thiol ester complex in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) capable of tethering a ubiquitin in thiol ester form that is transferred from E1, and a ubiquitin-ligase (E3). RING finger domain-containing E3s orchestrate the transfer of ubiquitin to a substrate by recruiting both the target protein and E2-S∼ubiquitin thiol ester and by helping position the attacking substrate lysine and the E2-bound donor ubiquitin optimally for conjugation (2). SCF (Skp1·Cullin·F-box) is a four-subunit RING E3 ligase complex with CUL1 (cullin 1) as scaffold that at its N terminus tethers the Skp1·F-box protein complex to target a substrate and utilizes its C terminus to dock the ROC1/Rbx1/Hrt1 RING finger subunit for recruiting an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (3–9). SCF-mediated polyubiquitination is activated by conjugation of Nedd8, a ubiquitin-like protein, to human CUL1 at lysine 720 (10, 11), most likely due to Nedd8-imposed conformational changes in CUL1 (12), thereby relieving autoinhibitory interactions between the extreme C terminus of CUL1 and ROC1 (13).

Accumulating evidence demonstrates a role for the Cdc34 E2 in SCF-dependent ubiquitination. Yeast Cdc34 (Ubc3) is essential for viability and is required for SCFCdc4-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Sic1 (see Refs. 3 and 4 and references therein). This regulation has been recapitulated by in vitro experiments that reconstitute the SCFCdcc4-dependent and Cdc34-catalyzed ubiquitination of Sic1 and the degradation of the modified substrate by the 26 S proteasome (3, 4, 14). Human Cdc34 (hCdc34)5 is highly conserved as it is able to complement growth defects by a temperature-sensitive cdc34 mutant yeast strain (cdc34-2, harboring the G58R mutation) at non-permissive temperature (15, 16). hCdc34 acts as an E2 for the ubiquitination of the human CDK inhibitor p27Kip1 by SCFSkp2 and IκBα by SCFβTrCP2, respectively (5, 16).

Previous studies have shown that the yeast Cdc34 C-terminal tail is required for the G1-to-S phase transition of the cell cycle and that this activity is probably mediated by the ability of the yeast Cdc34 C terminus to interact with SCF (17, 18). In humans, the C terminus of Cdc34 has been shown to interact with the SCF RING subcomplex (ROC1-CUL1(324–776)), and is indispensable for the RING subcomplex-dependent and Cdc34-catalyzed ubiquitin chain assembly (19). Intriguingly, E2–25K (human homolog of Ubc1), an E2 containing a C-terminal extension, was found to harbor a ubiquitin-associating domain (UBA) (20). These observations have prompted us to investigate whether the hCdc34 C terminus possesses the ubiquitin-binding activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Proteins for NMR

All DNA sequences encoding for the wild type and mutant forms of hCdc34 were cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector, and the human ubiquitin gene was cloned into pET-15b. Ub-linker-UBS1, consisting of ubiquitin, a linker peptide (SGG), and hCdc34 (residues 199–215), was cloned into pET-15b. To create point mutants, site-directed mutagenesis was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene).

Cdc34 (wild type or mutant), ubiquitin, Ub-linker-UBS1 proteins, and E1 were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3). To prepare 15N/13C- or 15N-labeled proteins, Rosetta (DE3) cells overexpressing GST-tagged Cdc34 or His-tagged ubiquitin were grown in M9 medium supplemented with [15N]NH4Cl/[15C]glucose or [15N]NH4Cl. His-ubiquitin or GST-Cdc34 was purified using Histrap or Hitrap-GST columns (GE Healthcare), respectively. The affinity tags were removed by thrombin digestion, and the protease was then removed by gel permeation chromatography using a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare).

Lys48-linked diubiquitin and triubiquitin chains, used in experiments as described in Table 3, Fig. 4, and supplemental Fig. S3, were synthesized by Ubc7 with the wild type ubiquitin at 25 °C, which yielded predominantly di- and triubiquitin chains. To separate di- and triubiquitin, the reaction mixture was applied to ion exchange Mono-S chromatography that was developed on a linear gradient from 0 to 1 m NaCl at pH 4.5 (21). Coomassie staining analysis was performed to track di- or triubiquitin-enriched fractions. For further separation, di- or triubiquitin-enriched fractions were pooled and subjected to chromatography on Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare).

TABLE 3.

CSP analysis of Kd (mm) for interactions between diubiquitin and hCdc34C or UBS1

Unless otherwise stated, CSP was carried out in a solution containing 50 mm MES, pH 5.5, and 100 mm NaCl.

| Non-labeled proteins | Lys48-[15N]di-Ub |

|

|---|---|---|

| Acceptor | Donor | |

| mm | mm | |

| hCdc34C | 0.049 ± 0.011 | 0.046 ± 0.007 |

| hCdc34C (pH 7.0)a | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.45 ± 0.11 |

| UBS1-peptide Ab | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| Non-labeled proteins | [15N]hCdc34C |

|

|---|---|---|

| UBS1 | UBS2 | |

| Lys48-diubiquitin | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.05 |

| Lys48-triubiquitinc | 0.03–0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Non-labeled proteins | Lys63-di-Ub |

|

|---|---|---|

| 15N-Acceptor | 15N-Donor | |

| UBS1-peptide Ab | 2.91 ± 1.27 | 1.22 ± 0.16 |

a In this experiment, 50 mm HEPES and 100 mm NaCl were used to maintain pH at 7.0.

b UBS1-peptide A, an hCdc34 fragment of residues 198–215.

c Lys48-triubiquitin greatly reduced the peak intensities of UBS1, and Kd for this interaction could not be precisely determined.

FIGURE 4.

UBS1 binds to Lys48-diubiquitin. The NMR experiments were carried out in a buffer containing 50 mm MES (pH 5.5) and 100 mm NaCl. A, CSP analysis. The UBS1-binding surface on 15N-labeled Lys48-linked diubiquitin is shown, with different colors denoting the CSP intensity. B, ribbon representations of Lys48- diubiquitin. The basic amino acids in the diubiquitin interface, such as Lys, Arg, and His, are differently labeled according to their originations. Single and double quotation marks represent the residues from acceptor and donor ubiquitin, respectively. C and D, PRE analysis. C, schematic representations of the UBS1-MTSL peptide. D, PRE experiments were carried out with 15N-labeled diubiquitin (0.1 mm) and UBS1-MTSL. Shown is the UBS1-MTSL-induced enhancement of the relaxation regions in diubiquitin. E, a model shows the dual binding orientation of the UBS1-MTSL peptide on Lys48-diubiquitin.

13C/15N-labeled Lys63-linked diubiquitin was prepared through enzymatic reaction using E1, Ubc13, and Mms2. The reaction contained His-tagged 13C/15N-labeled ubiquitin(1–74) and ubiquitin K63C or contained His-tagged ubiquitin(1–74) and 13C/15N-labeled ubiquitin K63C and was incubated at 37 °C for 2-h. The reaction mixture was applied to a Histrap column (GE Healthcare) to remove Ubc13 and Mms2, and then the eluted sample was directly applied to a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) to separate the diubiquitin from ubiquitin, E1, and other chemicals. The His tag was removed by thrombin digestion, and then the sulfhydryl group of Cys63 in the acceptor was aminoethylated by using a 25-fold molar excess of Aminoethyl-8 (Pierce) in 0.2 m Bistris propane (pH 8.5) (22).

All synthetic peptides were purchased from PEPTRON Inc. The concentrations of proteins and peptides were determined based on their absorbance at 280 nm (23).

NMR Experiments

NMR spectra were acquired using Bruker 800- and 900-MHz spectrometers (KBSI) at 25 °C. All chemical shift perturbation (CSP) experiments were performed in a buffer containing 10% D2O, NaCl at concentrations as specified and 50 mm MES (pH 5.5 and 6.0), BisTris (pH 6.5), HEPES (pH 7.0), or Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 and 8.0). The weighted CSP values were obtained using the square root of (ΔN2 + (ΔHN × 6)2), and the equilibrium binding constants were obtained by fitting the CSP data to the simple binding equation (24).

(1-Oxy-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-d-pyrroline-Δ3-methyl)-methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Spin labeling was carried out by mixing peptide (UBS1 or UBS2) with a 5-fold molar excess of MTSL. The mixture was incubated for 3 h at 25 °C. Non-reacted MTSL was removed by using desalting chromatography. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement experiments were performed in a solution containing 100 mm NaCl, 10% D2O, and 50 mm MES (pH 5.5) or HEPES (pH 7.0). Where indicated, spectra were measured after incubating the NMR samples with 10 mm DTT overnight, which removed the attached MTSL group from the peptide.

Yeast Complementation Assay

The yeast expression vector pRS416-GAL1-FLAG was constructed from pRS416 by inserting a GAL1/GAL10 promoter and a FLAG tag into the multicloning site. The temperature-sensitive cdc34-2 yeast mutant strain (25) was transformed with the pRS416-GAL1-FLAG vector alone or expression vectors that encoded for the wild-type hcdc34 or deletion mutants. Yeast colonies were seeded in SD-Ura medium supplemented with 2% glucose, and the cultures were incubated at 30 °C until the A600 reached 1.0–1.5. Equivalent amounts of the yeast cell culture, in which the volume of the culture was multiplied by the A600 values, were serially diluted and spotted onto two SD-Ura plates that were supplemented with 2% galactose, with one incubating at the permissive temperature (25 °C) and the other at non-permissive temperature (37 °C) for 3 days. To confirm equal expression of of the various versions of hCdc34 in the yeast cells, an equivalent amount of the cell culture was grown in galactose medium, and the cells were harvested and then lysed in SDS-loading buffer with glass beads. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma).

The in Vitro Ubiquitination Assays

The ubiquitination assays in this study employed [32P]GST-IκBα(1–54) or [32P]PK-Ub (as substrates), affinity-purified SCFβTrCP2 (as E3), ROC1-CUL1(324–776), Ubc12 (Nedd8 E2), and Nedd8, all of which were prepared as described previously (26). The E1 enzymes for ubiquitin and for Nedd8 (APP-BP1/Uba3) were purchased (Boston Biochem). Bovine ubiquitin was purchased from Sigma.

IκBα Ubiquitination

For the experiments shown in Fig. 6, A and B, Cdc34-S∼Ub and the E3·substrate complex were preformed. The Cdc34 charging reaction was assembled in a mixture (5 μl) that contained 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 10 nm okadaic acid, 2 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, PK-Ub (60 μm), E1 (0.1 μm), and hCdc34 (wild type or mutant in concentration as specified). The reaction was incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. To assemble the E3-substrate complex, a mixture (5 μl) containing SCFβTrCP2 (60 nm) and [32P]GST-IκBα(1–54) (80 nm) was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the above two reaction mixtures were combined (in a final volume of 10 μl) and incubated at 37 °C for times as indicated. The reaction products were visualized by autoradiography after separation by 4–12% SDS-PAGE.

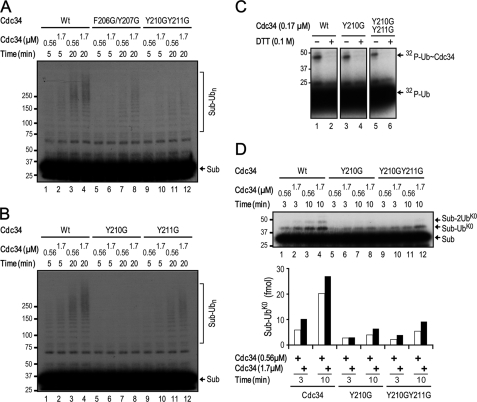

FIGURE 6.

The hCdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues contribute to SCF-dependent and Cdc34-catalyzed ubiquitination. The polyubiquitination (A and B) or monoubiquitination (D) of IκBα was carried out in the presence of the wild type or mutant form of hCdc34 as indicated. The reaction was incubated for the times specified. The influence of the hCdc34 mutation on the production of the monoubiquitinated species was quantified and is presented graphically. UbK0, lysineless ubiquitin. C, E2-S∼ubiquitin formation assay was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

For the experiment shown in Fig. 6C, the reaction was assembled as above with the exception that UbK0 was used in the precharging reaction in place of PK-Ub. The production of monoubiquitinated species was quantified using phosphorimaging.

E2·Ubiquitin Thiolester Formation

The E2-S∼ubiquitin formation assay was carried out in a reaction mixture (5 μl) that contained 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 10 nm okadaic acid, 2 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, [32P]PK-Ub (3.4 μm), E1 (0.1 μm), and hCdc34 or mutant (1.7 μm). The reaction was incubated for 3 min at 37 °C. Where indicated, DTT (0.1 m) was added postincubation.

Diubiquitin Synthesis

For the experiments shown in Fig. 7, Cdc34·S·[32P]Ub was prepared in a mixture (5 μl) that contained 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 10 nm okadaic acid, 2 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, [32P]PK-Ub (1.7 μm), E1 (0.1 μm), and Cdc34 (wild type or mutant in concentration, as specified). The reaction was incubated for 5 min at 37 °C.

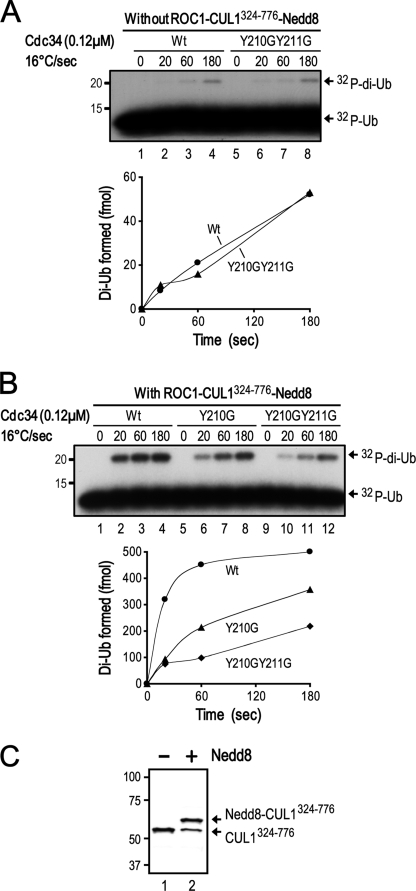

FIGURE 7.

The UBS1 Y210G/Y211G mutation is defective in diubiquitin synthesis that requires the neddylated RING subcomplex of SCF. The diubiquitin synthesis reaction was carried out in the absence (A) or presence (B) of the neddylated ROC1-CUL1(324–776). The influence of the hCdc34 mutation on the production of diubiquitin was quantified and is presented graphically. C, immunoblot analysis of an aliquot of the neddylation reaction mixture (as described under “Experimental Procedures”).

A neddylation mix was assembled in a mixture (4 μl) that contained 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 10 nm okadaic acid, 2 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, ROC1-CUL1(324–776) (1.2 μm), Nedd8 (6 μm), APP-BP1/Uba3 (0.16 μm), and Ubc12 (4 μm). The reaction was incubated for 5 min at 37 °C.

The Cdc34·S·[32P]Ub mix was combined with or without the neddylation mix. The resulting mixture was then chased (in a final volume of 10 μl) with bovine Ub (170 μm) at 16 °C for times as indicated. After separation by SDS-PAGE, the production of diubiquitin species was quantified using phosphorimaging.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

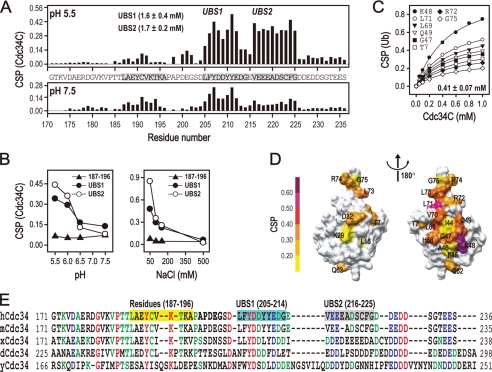

The hCdc34 C Terminus Contains Two Distinct Motifs Capable of Direct Interactions with Ubiquitin

By employing NMR CSP, we identified direct interactions between ubiquitin and the hCdc34 C terminus. In this case, the purified hCdc34 C-terminal fragment spanning amino acids 170–236, designated as hCdc34C, was 15N-labeled and mixed with ubiquitin. Significant CSP was observed at pH 5.5 in two major hCdc34C areas, amino acid residues 205–215 and 216–225 (Fig. 1A), which are named ubiquitin-binding site 1 and 2 (UBS1 and UBS2), respectively. The ubiquitin-binding constants (Kd) for UBS1 and UBS2 were determined at 1.6 and 1.7 mm (Fig. 1A), respectively, by CSP experiments performed with 15N-labeled hCdc34C and increasing concentrations of ubiquitin. Notably, the third hCdc34C segment spanning amino acids 187–196 exhibited detectable CSP as well (Fig. 1A), but its magnitude was too weak to allow the determination of its Kd. The UBS1- and UBS2-mediated interactions were sensitive to both pH and salt (Table 1). Optimal interactions required acidic pH (Fig. 1, A and B, left). The addition of NaCl at 500 mm abolished the interaction by either UBS1 or UBS2 (Fig. 1B, right). Of note, no CSP was detected in hCdc34C amino acids 226–236, which are composed of a stretch of highly acidic residues (Asp/Glu), similar to those in UBS1 or -2 (Fig. 1A). It is thus unlikely that electrostatic interactions provided by acidic residues enriched in hCdc34C serve as the sole determinant dictating the binding to ubiquitin.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of the hCdc34C UBS1 and UBS2 motifs for binding to ubiquitin. A, the CSP experiments were carried out with 15N-labeled hCdc34C (0.1 mm) in the presence of ubiquitin (1.5 mm) in a buffer containing 50 mm MES (pH 5.5) or Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, and 5 mm DTT. The bar graphs show the CSP signals (at pH 5.5 or 7.5) measured across the entire hCdc34C region, exhibiting two regions designated as UBS1 and UBS2. The Kd values of UBS1 and UBS2 are indicated. B, the plots show the averaged CSP signal determined for 15N-labeled hCdc34C (0.1 mm) in the presence of ubiquitin (1.5 mm) at a range of pH (left, with 100 mm NaCl) or salt concentration (right, at pH 5.5). C, the CSP experiments were carried out with 15N-labeled ubiquitin (0.2 mm) in the presence of increasing concentrations of hCdc34C in a buffer containing 50 mm MES (pH 5.5), 100 mm NaCl, and 5 mm DTT. The plot shows the CSP response at various ubiquitin residues (as specified) as a function of hCdc34C concentration. D, the hCdc34C-binding surface on 15N-labeled ubiquitin is shown, with different colors denoting the CSP intensity. E, sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of Cdc34 homologs. The red, blue, and green colors represent residues that are identical, strongly conserved, and conserved, respectively. Residues 187–196 and the UBS1 and UBS2 regions in Cdc34C are highlighted in yellow, cyan, and gray, respectively.

TABLE 1.

CSP analysis of Kd (mm) for interactions between 15N-labeled hCdc34C and ubiquitin or mutants

Unless otherwise stated, CSP was carried out in a solution containing 50 mm MES, pH 5.5, and 100 mm NaCl.

| Non-labeled proteins | [15N]hCdc34C |

|

|---|---|---|

| UBS1 | UBS2 | |

| mm | mm | |

| Ub (50 mm NaCl)a | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.92 ± 0.14 |

| Ub (100 mm NaCl)a | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Ub (150 mm NaCl)a | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 0.8 |

| H68A-ubiquitin | 0.91 ± 0.19 | 0.52 ± 0.08 |

| V70A-ubiquitinb | >5 | >5 |

| I44A-ubiquitin | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| Nedd8c | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 |

| Non-labeled proteins | [15]Ubiquitin | |

|---|---|---|

| hCdc34C | 0.41 ± 0.07 | |

| hCdc34C (pH 7.0)d | 2.1 ± 0.4 | |

| UBS1-peptide Ae | 2.0 ± 0.7 | |

a The CSP of 15N-labeled hCdc34C with ubiquitin was measured in the presence of 50, 100, or 150 mm NaCl, respectively.

b The plateau of the CSP was not observed even in the presence of 3.5 mm of V70A, and thus the precise Kd values could not be determined.

c In this experiment, the highest concentration of Nedd8 used was 1.0 mm due to limited solubility of Nedd8 at pH 5.5.

d In this experiment, 50 mm HEPES and 100 mm NaCl were used to maintain pH at 7.0.

e UBS1-peptide A, an hCdc34 fragment of residues 198–215.

We mapped the hCdc34C-binding surface on ubiquitin by a CSP experiment with 15N-labeled ubiquitin and increasing concentrations of hCdc34C. As shown (Fig. 1C), CSP signals were observed with ubiquitin residues (in order of descending magnitude): Lys48, Leu71, Leu69, Gln49, Val70, Leu73, Gly47, Thr7, Arg74, Arg72, and Gly75. These findings suggest a model for the hCdc34C-binding surface on ubiquitin (Fig. 1D). Although this interaction surface is similar to those mapped for other ubiquitin-binding domains (27, 28), it is narrower and extended into the ubiquitin C-terminal tail (Leu71–Gly75). In addition, these CSP titration experiments determined the Kd for hCdc34C at 0.41 ± 0.07 mm. Thus, the Kd of hCdc34C is significantly lower than that determined for UBS1 or UBS2 (Fig. 1A), suggesting that UBS1, UBS2, and possibly hCdc34(187–196) act synergistically to enhance the affinity of hCdc34C for ubiquitin. Of note, sequence alignment analysis reveals that UBS1 is more conserved than UBS2 (Fig. 1E).

Given the roles for ubiquitin Ile44, His68, and Val70 in mediating interactions with ubiquitin-binding domains (27), we sought to determine their contributions in binding to hCdc34C. For this purpose, CSP experiments were performed with 15N-labeled hCdc34C in the presence of ubiquitin I44A, H68A, or V70A. Of these ubiquitin mutants examined, V70A exhibited a pronounced defect in binding to hCdc34C (Table 1). Of note, the plateau of the CSP of 15N-labeled hCdc34C was not observed even in the presence of 3.5 mm V70A, precluding the precise measurement of its Kd value. No significant effect was observed with I44A or H68A (Table 1). Thus, the hCdc34C-ubiquitin Val70 interaction appears to have a significant role in mediating the binding of hCdc34C to ubiquitin.

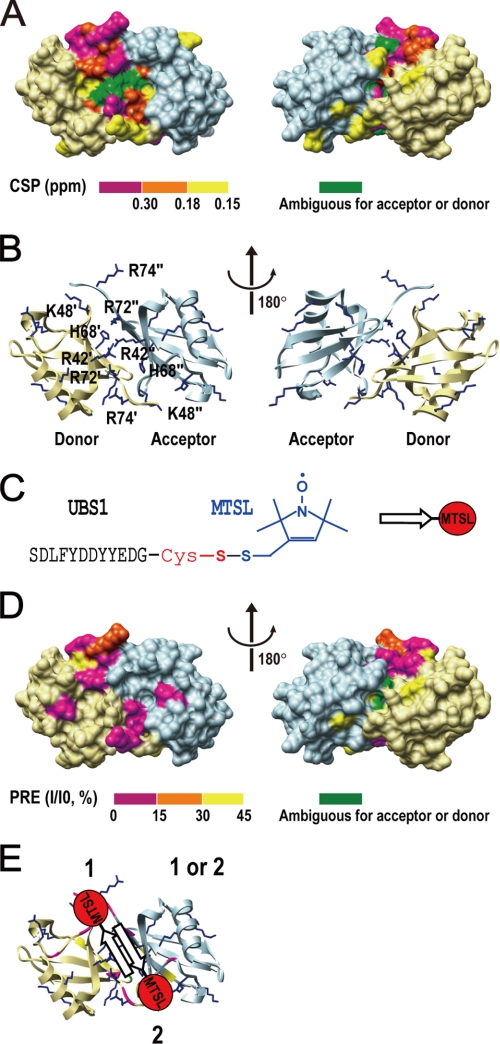

The hCdc34C UBS1 and UBS2 Motifs Exhibit a Dual Ubiquitin Binding Orientation

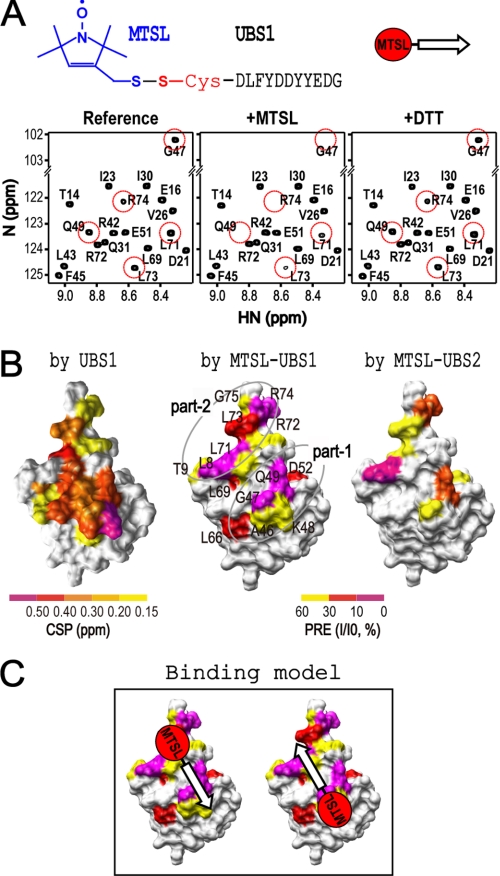

To examine the mode of interactions between ubiquitin and UBS1 or -2, we employed a paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) assay, which is a highly effective NMR technique for measuring the orientation of a protein-protein interaction (29). In this system, 15N-labeled ubiquitin was mixed with an MTSL-coupled UBS1 or -2 peptide (diagramed in Fig. 2A, top), followed by the acquisition of 1H-15N HSQC spectra. The results revealed that MTSL-UBS1 diminished the NMR peak intensity of ubiquitin residues Arg74, Leu73, Leu71, Gln49, and Gly47 (Fig. 2A, compare left and middle) and that this diminishing activity was reversed by treatment with DTT (Fig. 2A, right), indicating a MTSL-UBS1-specific effect. In addition, the NMR spectrum at ubiquitin residues Ala46 and Leu8 was reduced by MTSL-UBS1 as well (data not shown). These results demonstrated interactions between the UBS1 peptide and ubiquitin residues Arg74, Leu73, Leu71, Gln49, Ala46, Gly47, and Leu8, which fall into two separate regions, with “parts 1 and 2” containing ubiquitin Ala46/Gly47/Gln49 and Leu8/Leu71/Leu73/Arg74, respectively (Fig. 2B, middle). Similar observations were observed with the MTSL-UBS2 peptide (Fig. 2B, right). Given the short length of the peptides (11 amino acids) used in the PRE experiments, it is impossible for a single UBS peptide to cover both ubiquitin parts 1 and 2 in a single binding event (Fig. 2B). Thus, it is most likely that UBS1 and UBS2 bind to ubiquitin in two distinct orientations (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

PRE analysis of the binding surface and orientation of UBS1 or UBS2 on ubiquitin. All NMR experiments were performed in a buffer containing 50 mm MES (pH 5.5) and 100 mm NaCl. A, top, schematic presentation of the MTLS-labeled UBS1 peptide. Note that this peptide contains an N-terminal Cys residue for spin labeling. Bottom, the HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled ubiquitin (0.1 mm) were recorded in the absence (Reference) and presence (+MTSL) of the MTSL-UBS1 peptide, respectively. In a separate sample (+DTT), DTT (10 mm) was incubated with 15N-labeled ubiquitin and MTSL-UBS1 overnight. The detailed procedure is described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, left, the CSP surface of 15N-labeled ubiquitin (0.2 mm) in the presence of the UBS1 peptide (1.5 mm) was determined and is shown based on CSP intensity. Middle, the paramagnetic relaxation enhanced residues on 15N-labeled ubiquitin in the presence of the MTSL-UBS1 peptide are shown. The paramagnetic relaxation-enhanced regions can be divided into two separated regions, in which “part 1” contains Ala46, Gly47, and Gln49, and “part 2” contains Leu8, Leu71, Leu73, and Arg74. Right, the same PRE experiment was performed for the MSTL-UBS2 peptide. UBS2 contains Cys (GEVEEEADSCFG), which can react with MTSL. The paramagnetic relaxation-enhanced regions by the MTSL-UBS2 peptide are very similar to those enhanced by the MTSL-UBS1 peptide. C, models for the dual ubiquitin binding orientations for MTSL-UBS1.

As revealed by both CSP analysis (supplemental Fig. S1A) and CD experiments (supplemental Fig. S1B), neither UBS1 nor UBS2 displayed any defined secondary structures (α-helix and β-strand) when bound to ubiquitin or triubiquitin. We have been unable to deduce the structure of UBS1 bound to ubiquitin from NMR data using the CYANA program (30) due to the dual ubiquitin binding mode of UBS1 (see below).

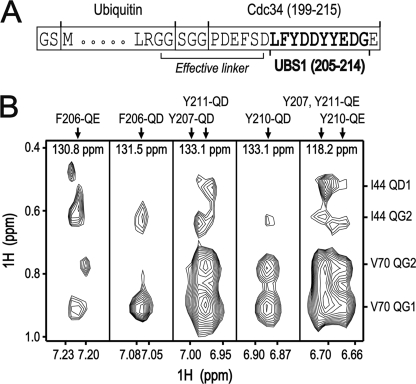

The UBS1 Aromatic Residues Participate in Binding to Ubiquitin

We analyzed the binding mode of UBS1 further by NOE cross-peak analysis, which reveals the close proximity of a pair of interacting amino acids by the appearance of their NOE cross-peaks. In this experiment, we employed a Ub-linker-UBS1 fusion protein (diagrammed in Fig. 3A) to enhance the binding affinity of UBS1 for ubiquitin. As shown (Fig. 3B), all of the UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206, Tyr207, Tyr210, and Tyr211) exhibited NOE cross-peaks with ubiquitin Val70 and with Ile44, albeit at a lesser degree. Thus, it appears that when bound to ubiquitin, all of the UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206, Tyr207, Tyr210, and Tyr211) are positioned in the vicinity of ubiquitin Val70. In further support of these findings, UBS1 in the ubiquitin fusion exhibited relatively strong rigidity as revealed by the analysis of the order parameters from the observed T1, T2, and heteronuclear NOE values (supplemental Fig. S2B). By contrast, the UBS1 motif in the context of hCdc34C was flexible (data not shown). These results demonstrated an intramolecular interaction between ubiquitin and UBS1 in the fusion protein. In addition, analysis of the residual dipolar coupling values suggests that the fused UBS1 bound to ubiquitin with two different orientations (supplemental Fig. S2C). Of note, we also detected Ub-UBS1 intramolecular interactions with a fusion protein containing N-terminally located UBS1, followed by a linker of GGSGG and then ubiquitin. The overall binding mode of this fusion is similar to that of Ub-linker (SGG)-UBS1, albeit with lower levels of CSP (data now shown). Such discrepancy can be explained by the well known structural flexibility of the ubiquitin C-terminal tail that may allow the movement of the C-terminally located UBS1 for interactions with ubiquitin in the context of Ub-linker (SGG)-UBS1.

FIGURE 3.

NOE cross-peak analysis of the interactions between UBS1 and ubiquitin. A, a diagram for the ubiquitin linker-UBS1 fusion protein. B, NOE cross-peaks were observed in 13C-resolved three-dimensional aromatic NOESY-HSQC spectrum of 13C/15N-labeled ubiquitin linker-UBS1 hybrid protein. Ubiquitin Val70 and Ile44 had NOE cross-peaks with all of the UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206, Tyr207, Tyr210, and Tyr211).

To assess the contribution by UBS1 residues in binding to ubiquitin, we measured and compared Kd for the wild type and mutant peptides in the CSP assay using 15N-labeled ubiquitin (Table 2). Replacement of Phe206/Tyr207, Tyr210/Tyr211, or Asp208/Asp209, by GG all decreased binding affinity of UBS1 for ubiquitin. Taken together, these results suggest a role for UBS1 aromatic residues in participating in interactions with ubiquitin.

TABLE 2.

CSP analysis of Kd (mm) for interactions between 15N-labeled ubiquitin and UBS1 or mutants

CSP was carried out in a solution containing 50 mm MES, pH 5.5, and 100 mm NaCl.

| Non-labeled proteins | [15N]Ubiquitin |

|---|---|

| mm | |

| CDLFYDDYYEDG | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| CDLGGDDYYEDG | ∼4.0 |

| CDLFYDDGGEDG | Very low CSPa |

| CDLFYGGYYEDG | Very low CSPa |

| CDLGGDDGGEDG | No CSP |

a Very weak CSP signals precluded the determination of the Kd values.

UBS1 Binds to Lys48-Ub Chains Preferentially

UBS1 displayed a higher affinity for Lys48-linked diubiquitin than for monoubiquitin, with a drop of Kd by 7-fold for UBS1 and 4-fold for UBS2 (compare Table 1 and Table 3). In the form of hCdc34C, UBS1 and UBS2 exhibited different Kd values for Lys48-diubiquitin (0.22 ± 0.03 versus 0.40 ± 0.05 mm) (Table 3), suggesting that each site independently binds to one diubiquitin molecule. CSP analysis revealed that the UBS1-binding surface on either the donor or acceptor ubiquitin in a diubiquitin molecule was similar to that mapped on monoubiquitin (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). Moreover, CSP located UBS1-binding to the interface of the Lys48-diubiquitin (Fig. 4, A and B). Intriguingly, the Kd for 15N-labeled diubiquitin to UBS1 is 0.20 ± 0.05 mm, which is similar to that determined for 15N-labeled hCdc34C to diubiquitin (0.22 ± 0.03 mm) (Table 3). It is thus likely that UBS1 interacts with both the acceptor and donor ubiquitin of diubiquitin in a single binding event because otherwise, the UBS1 motif of 15N-labeled hCdc34C would have displayed an increased affinity. In addition, PRE experiments have determined the binding orientations of UBS1 on a diubiquitin molecule (Fig. 4, C and D, and supplemental Fig. S3D). Lys48-diubiquitin is characterized by antiparallel 2-fold symmetry and a highly basic interface (31). Taken together, these findings support a model in which UBS1 binds to the interface of Lys48-diubiquitin in a dual orientation fashion (Fig. 4E).

It was observed that UBS1 bound to Lys48-diubiquitin with affinity much higher than to Lys63-diubiquitin (Table 3). Specifically, the affinity of UBS1 for the acceptor Ub in the Lys48-diubiquitin is at least 14-fold higher than that in the Lys63-diubiquitin. On the donor ubiquitin, UBS1 exhibited affinity for the Lys48-diubiquitin that is at least 6-fold greater than for the Lys63-diubiquitin (Table 3). In addition, a GST-based pull-down assay revealed strong interactions between hCdc34 and a Lys48-tetraubiquitin chain (supplemental Fig. S4).

In all, these findings suggest that UBS1 and UBS2 bind to a Lys48-linked diubiquitin molecule specifically with a stoichiometry of 1:1, occupying both the donor and acceptor ubiquitin moieties. It should be cautioned that the double side ubiquitin binding property of UBS1/UBS2 might have resulted in an inaccurate determination of Kd for ubiquitin because during CSP titration, one UBS1/UBS2 site may be engaged in interactions with two ubiquitin molecules simultaneously.

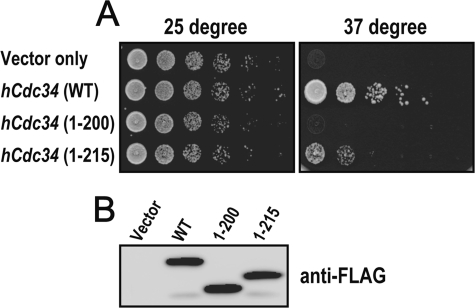

UBS1 Contributes to the Function of hCdc34 in Vivo and in Vitro

We employed a yeast complementation assay to evaluate the function of hCdc34 UBS1 and UBS2 in vivo. Previous studies have shown that the full-length hCdc34 but not its truncated form (hCdc34(1–200)) is able to support growth in the temperature-sensitive cdc34-2 yeast strain at non-permissive temperature (37 °C) when the endogenous Cdc34 is disabled (16). As shown (Fig. 5A), hCdc34(1–215) appeared to allow temperature-sensitive cdc34-2 to grow at 37 °C, whereas hCdc34(1–200) was completely inactive. However, the full-length hCdc34 supported the growth far better than hCdc34(1–215). Note that under these conditions, the wild type and truncated versions of hCdc34 were expressed equally (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the Cdc34 UBS1 motif (spanning residues 205–215) alone is capable of supporting the function of the Cdc34 C terminus in vivo, albeit to a limited extent. hCdc34(216–236) containing the UBS2 motif is clearly required for the full function of Cdc34 in cells.

FIGURE 5.

The UBS1-containing hCdc34(1–215) rescues cell viability in yeast. A, growth assay. Colony growth is shown for the temperature-sensitive cdc34-2 yeast strain transformed with vectors expressing the wild type hCdc34 or truncated forms, as indicated, at permissive (left) or non-permissive (right) temperature. The experimental details are described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, immunoblot analysis. Galactose-induced whole yeast cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by anti-FLAG Western blot to monitor the expression of hCdc34, hCdc34(1–200), and hCdc34(1–215).

To evaluate the contribution by hCdc34 UBS1 and UBS2 in ubiquitination, we initially employed a reconstituted IκBα ubiquitination assay to determine whether mutations within UBS1 or UBS2 might impair the conjugation activity of Cdc34. This assay contains IKKβ-phosphorylated GST-IκBα(1–54) as substrate, affinity-purified SCFβTrCP2 as E3, hCdc34 in wild type or mutant form as E2, E1, and ubiquitin (26). Of four mutants tested (F206G/Y207G, D208G/D209G, Y210G/Y211G, and V216/F224G), Y210G/Y211G exhibited defects in ubiquitination in comparison with the wild type E2 (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 1–4 with lanes 9–12). F206G/Y207G appeared defective as well, albeit to a lesser degree when compared with Y210G/Y211G (Fig. 6A, lanes 5–8). Neither D208G/D209G nor V216/F224G impaired ubiquitination (data not shown). As revealed by subsequent ubiquitination analysis, Y210G displayed a more pronounced decrease in ubiquitination than Y211G (Fig. 6B). Of note, neither Y210G/Y211G nor Y210G impaired the ability of Cdc34 to form E2-S∼ubiquitin (Fig. 6C). Thus, substitution of UBS1 aromatic residues by glycine appears to inhibit the ability of Cdc34 to catalyze the ubiquitination of IκBα, albeit at varying degrees. Among these aromatic residues, Cdc34 Tyr210 is likely to have the most pronounced role in catalysis. In addition, GST-based pull-down experiments revealed that replacement of UBS1 aromatic residues by glycine did not alter the interactions between Cdc34 and the SCF RING subcomplex (supplemental Fig. S5), thereby excluding the possibility that altered E2-RING interactions are attributable to the observed decrease in ubiquitination.

We next determined whether Y210G/Y211G or Y210G inhibits the ability of Cdc34 to catalyze the ligation of a single ubiquitin to GST-IκBα(1–54) using lysineless ubiquitin. The results showed that either single or double mutation decreased monoubiquitination by as much as 4-fold (Fig. 6D). These findings pointed to a role for Cdc34 Tyr210 in positioning the donor ubiquitin (thiol ester linked to Cdc34) for chemical reactions with the receptor lysine (on either the substrate or ubiquitin). To test this possibility, we compared the wild type Cdc34 and Y210G/Y211G or Y210G to catalyze diubiquitin synthesis in the absence or presence of the SCF RING subcomplex, ROC1-CUL1(324–776), using an assay as described previously (26). The results showed that in the absence of ROC1-CUL1(324–776), Y210G/Y211G exhibited activity for diubiquitin synthesis at levels comparable with the wild type (Fig. 7A). In keeping with this observation, none of the Cdc34 UBS1/UBS2 mutants (F206G/Y207G, D208G/D209G, Y210G/Y211G, V216/F224G, and F206G/Y207G/Y210G/Y211G) showed defects in ubiquitination catalyzed by E2 only (supplemental Fig. S6). Consistent with previous observations (26), the addition of the neddylated ROC1-CUL1(324–776) stimulated the wild type Cdc34 for the production of diubiquitin (Fig. 7, compare A (lanes 1–4) with B (lanes 1–4); also see graphs). By contrast, Y210G/Y211G or Y210G was poorly stimulated by the neddylated ROC1-CUL1(324–776) for diubiquitin synthesis (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 1–4 with lanes 5–12; graph). Of note, under the conditions used, 70% of CUL1(324–776) was neddylated as revealed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these findings support a hypothesis that Cdc34 Tyr210 may help orient the donor ubiquitin for conjugation in a manner that depends on the SCF neddylated RING subcomplex.

A Role for the UBS1 Aromatic Residues in SCF-dependent and hCdc34-catalyzed Ubiquitination

In summary, the results of NMR, genetic complementation, and ubiquitination experiments suggest strongly a role of the Cdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues in SCF-dependent ubiquitination. First, the PRE experiments have mapped the UBS1-binding surface on ubiquitin to the proximity of ubiquitin Lys48 and C-terminal tail (Fig. 2B), both of which are key sites for catalysis. Second, the NOE cross-peak analysis suggests that when bound to ubiquitin in one orientation, the Cdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206, Tyr207, Tyr210, and Tyr211) are probably positioned in the vicinity of ubiquitin Val70 (Fig. 3). Third, replacement of UBS1 aromatic residues by glycine or of ubiquitin Val70 by alanine decreased UBS1-ubiquitin affinity interactions (Tables 1 and 2), underscoring the significance of these residues in mediating the binding of UBS1 to ubiquitin. Fourth, yeast complementation experiments have suggested a role for the hCdc34 UBS1 motif in supporting the function of this E2 in vivo (Fig. 5). Fifth, reconstituted IκBα ubiquitination analysis revealed a role for each adjacent pair of UBS1 aromatic residues (Phe206/Tyr207 and Tyr210/Tyr211) in conjugation, with Tyr210 exhibiting the most pronounced catalytic function (Fig. 6, A and B). Last, Cdc34 Tyr210 appears to be required for the transfer of the donor ubiquitin to a receptor lysine on either a substrate (Fig. 6D) or a ubiquitin in a manner that depended on the SCF neddylated RING subcomplex (Fig. 7). Based on these findings, it is tempting to speculate that the Cdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues help orient the donor ubiquitin C-terminal tail for conjugation.

Previous studies suggest a role for hCdc34 catalytic core residues Ser95 and Glu108/Glu112 in the function of the donor ubiquitin, because mutations at these sites abolish IκBα mono- and polyubiquitination as well as diubiquitin synthesis in the presence or absence of the neddylated ROC1-CUL1(324–776) (26). Intriguingly, the Cdc34 Y210G/Y211G mutation did not affect unassisted diubiquitin synthesis by Cdc34 alone (Fig. 7A). These observations suggest that both the hCdc34 catalytic core and C-terminal UBS1 motif contribute to the positioning of the donor ubiquitin. However, the engagement of the Cdc34 UBS1 in this activity is strictly dependent on the neddylated SCF RING subcomplex (ROC1-CUL1(324–776)). It can be speculated that UBS1 itself is incapable of productive interactions with the hCdc34 Cys93-bonded ubiquitin (within the Cdc34·S·ubiquitin complex) due to its low affinity (with Kd measured at greater than millimolar range; see Table 1). However, the hCdc34 UBS1 could be brought into the vicinity of the donor ubiquitin by the SCF RING complex, which has been shown to interact with the Cdc34 C terminus (19). Recently, the nature of Cdc34 C tail-RING complex interaction was uncovered; Kleiger et al. (32) demonstrates that the acidic tail of Cdc34 interacts with the basic canyon located on the CUL1 C terminus. Once brought near the donor ubiquitin, the hCdc34 UBS1 aromatic residues, Tyr210 in particular, may be in a position to engage in interactions with the ubiquitin C-terminal tail. Consequently, the proper orientation of the donor Ub Gly76 is established, aligning with Lys48 of the acceptor ubiquitin for conjugation.

In addition to its postulated role for positioning the donor ubiquitin for conjugation as stated above, the hCdc34 UBS1 (and probably UBS2) may have a role in the assembly of polyubiquitin chains. Given their capability to bind ubiquitin in two distinct orientations (Fig. 2B) and high affinity for Lys48-linked diubiquitin with a stoichiometry of 1:1 (Table 3 and Fig. 4), both UBS1 and UBS2 could conceivably help align the donor and the receptor ubiquitin for conjugation or provide sites for accommodating ubiquitin chains. However, given the role for UBS1 in the function of donor ubiquitin in catalysis and the possible redundancy of UBS1 and UBS2, we have been unsuccessful in dissecting the role of UBS1/UBS2 in the receptor ubiquitin for chain assembly using mutagenesis approaches.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM61051 and CA095634 (to Z.-Q. P.). This work was also supported by the NMR Research Programs of the Korea Basic Science Institute (Grants T3022E (to K.-S. R.) and T29221 (to Y. H. J.)).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- hCdc34

- human Cdc34

- Bistris propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- UBA

- ubiquitin-associating domain

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- CSP

- chemical shift perturbation

- MTSL

- (1-oxy-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-d-pyrroline-Δ3-methyl)-methanethiosulfonate

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- NOE

- nuclear Overhauser effect.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickart C. M. (2004) Cell 116, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman R. M., Correll C. C., Kaplan K. B., Deshaies R. J. (1997) Cell 91, 221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skowyra D., Craig K. L., Tyers M., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W. (1997) Cell 91, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan P., Fuchs S. Y., Chen A., Wu K., Gomez C., Ronai Z., Pan Z. Q. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta T., Michel J. J., Schottelius A. J., Xiong Y. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 535–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamura T., Koepp D. M., Conrad M. N., Skowyra D., Moreland R. J., Iliopoulos O., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Elledge S. J., Conaway R. C., Harper J. W., Conaway J. W. (1999) Science 284, 657–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skowyra D., Koepp D. M., Kamura T., Conrad M. N., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W. (1999) Science 284, 662–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seol J. H., Feldman R. M., Zachariae W., Shevchenko A., Correll C. C., Lyapina S., Chi Y., Galova M., Claypool J., Sandmeyer S., Nasmyth K., Shevchenko A., Deshaies R. J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1614–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Z. Q., Kentsis A., Dias D. C., Yamoah K., Wu K. (2004) Oncogene 23, 1985–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha A., Deshaies R. J. (2008) Mol. Cell 32, 21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duda D. M., Borg L. A., Scott D. C., Hunt H. W., Hammel M., Schulman B. A. (2008) Cell 134, 995–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamoah K., Oashi T., Sarikas A., Gazdoiu S., Osman R., Pan Z. Q. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12230–12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma R., McDonald H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Deshaies R. J. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prendergast J. A., Ptak C., Arnason T. G., Ellison M. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9347–9352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Block K., Appikonda S., Lin H. R., Bloom J., Pagano M., Yew P. R. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 1421–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ptak C., Prendergast J. A., Hodgins R., Kay C. M., Chau V., Ellison M. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26539–26545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver E. T., Gwozd T. J., Ptak C., Goebl M., Ellison M. J. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 3091–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu K., Chen A., Tan P., Pan Z. Q. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 516–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkley N., Shaw G. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47139–47147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickart C. M., Haldeman M. T., Kasperek E. M., Chen Z. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 14418–14423 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piotrowski J., Beal R., Hoffman L., Wilkinson K. D., Cohen R. E., Pickart C. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23712–23721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mach H., Middaugh C. R., Lewis R. V. (1992) Anal. Biochem. 200, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi Y. S., Jeon Y. H., Ryu K. S., Cheong C. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 3323–3328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willems A. R., Lanker S., Patton E. E., Craig K. L., Nason T. F., Mathias N., Kobayashi R., Wittenberg C., Tyers M. (1996) Cell 86, 453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazdoiu S., Yamoah K., Wu K., Pan Z. Q. (2007) Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 7041–7052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dikic I., Wakatsuki S., Walters K. J. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 659–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryu K. S., Lee K. J., Bae S. H., Kim B. K., Kim K. A., Choi B. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36621–36627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bomar M. G., Pai M. T., Tzeng S. R., Li S. S., Zhou P. (2007) EMBO Rep. 8, 247–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryabov Y., Fushman D. (2006) Proteins 63, 787–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleiger G., Saha A., Lewis S., Kuhlman B., Deshaies R. J. (2009) Cell 139, 957–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.