Abstract

KLF4 (Krüppel-like factor 4) has been implicated in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) differentiation induced by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). However, the role of KLF4 and mechanism of KLF4 actions in regulating TGF-β signaling in VSMCs remain unclear. In this study, we showed that TGF-β1 inhibited cell cycle progression and induced differentiation in cultured rat VSMCs. This activity of TGF-β1 was accompanied by up-regulation of KLF4, with concomitant increase in TβRI (TGF-β type I receptor) expression. KLF4 was found to transduce TGF-β1 signals via phosphorylation-mediated activation of Smad2, Smad3, and p38 MAPK. The activation of both pathways, in turn, increased the phosphorylation of KLF4, which enabled the formation of KLF4-Smad2 complex in response to TGF-β1. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies and oligonucleotide pull-down assays showed the direct binding of KLF4 to the KLF4-binding sites 2 and 3 of the TβRI promoter and the recruitment of Smad2 to the Smad-responsive region. Formation of a stable KLF4-Smad2 complex in the promoter's Smad-responsive region mediated cooperative TβRI promoter transcription in response to TGF-β1. These results suggest that KLF4-dependent regulation of Smad and p38 MAPK signaling via TβRI requires prior phosphorylation of KLF4 through Smad and p38 MAPK pathways. This study demonstrates a novel mechanism by which TGF-β1 regulates VSMC differentiation.

Keywords: Cell/Differentiation, Cytokines, Gene/Regulation, Receptors, Signal Transduction, Transcription

Introduction

Proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)2 plays a key role in the pathogenesis of a variety of proliferative vascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, restenosis, and hypertension (1, 2). Several lines of evidence have shown that the factors controlling VSMC proliferation and growth inhibition, including various growth factors, signal transduction molecules, and transcription factors, constitute a complex functional network. Krüppel-like factors (KLFs), retinoic acid receptor-α, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor, and TβRI and TβRII (transforming growth factor-β type I and II receptor, respectively) are expressed in VSMCs and are components of such a network (3–8). Our recent study demonstrates that KLF4 (GKLF) inhibits proliferation by PDGF receptor-mediated but not by retinoic acid receptor-α-mediated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and ERK signaling in VSMCs (4). However, the actual relationship between KLF4 and TβR in the regulation of VSMC proliferation and growth inhibition is not fully understood.

KLF4 is a member of the Sp1 transcription factor family characterized by three C2H2 zinc finger motifs, mainly involved in regulating cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis, by controlling the expression of a large number of genes with GC/GT-rich promoters. KLF4 has been identified in VSMCs (9) and is induced by shear stress (10, 11), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (12), and PDGF-BB (13). Studies from the Owens laboratory (13) suggest that KLF4 not only mediates the repressive effects of PDGF-BB on VSMC gene expression but also represses the TGF-β1-dependent increase in VSMC differentiation markers, such as SM α-actin and SM22α (14). These results imply that KLF4 may promote the dedifferentiated phenotype. However, we and others showed that KLF4 can activate the transcription of p53 and inhibit VSMC proliferation (3, 4, 15), indicating that KLF4 might function as a pleiotropic factor, depending on the interaction partner(s) and the cellular context in VSMCs (16).

TGF-β signaling is involved in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, cellular homeostasis, and other cellular functions (17). TGF-β signals to the nucleus by binding to a heteromeric complex of TβRI and TβRII, which contains a cytoplasmic transmembrane serine/threonine kinase domain. Upon ligand binding and activation, the TβRII kinase phosphorylates the TβRI. The activated TβRI specifically recognizes and phosphorylates Smad2 and −3. Phosphorylated Smad2/3 subsequently translocate to the nucleus with Smad4 and activate various transcription programs through binding to a Smad-binding element (18, 19). In addition to the canonical Smad pathway, TGF-β also activates the MAPK signaling pathways, such as the p38 MAPK (20) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (21), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway (8), and Wnt signaling (22), many of which probably cross-talk with Smad signaling. Despite numerous signaling studies, however, the specific contribution of TGF-β signaling to VSMC phenotypic modulation has not been fully elucidated.

The role of the KLF family in the regulation of TGF-β signaling has been the subject of considerable investigation. For instance, KLF4 interacts with Smad3 directly to inhibit myofibroblast differentiation (23). Recent evidence shows that KLF14 acts as a cross-talk regulator with TGF-β signaling to repress the TβRII in Panc1 cells via direct binding to GC-rich sequences of TβRII promoter (24). KLF2 was reported to inhibit TGF-β signaling by abrogating the phosphorylation of Smad2 and suppressing both Smad3/4- and AP-1-mediated activation of TGF-β inducible promoters in cultured endothelial cells or in vivo (25). Moreover, when TGF-β signaling is activated in epithelial cells, KLF5 forms a complex with Smads on the p15 promoter to induce its transcription (16). Taken together, these findings suggest that the KLF family may play a key role in TGF-β signaling. However, the precise mechanism whereby KLF4 regulates TGF-β signaling in VSMCs is still poorly understood. Given that TGF-β regulates KLF4, there exists an interesting possibility that one of the TGF-β-activated pathways regulates KLF4. Because KLF4 exerts antiproliferative effects through multiple pathways in VSMCs, we hypothesized that KLF4 enhances TGF-β signaling via TβR and that KLF4 is itself regulated by TGF-β.

In this study, we sought to elucidate whether and how TGF-β-mediated KLF4 expression regulates TGF-β signaling in VSMCs. KLF4 was found to induce TβRI expression and activation of Smad2/3 and p38 MAPK signaling in TGF-β1-treated VSMCs. The increase in Smad2 and p38 MAPK, in turn, promoted KLF4 phosphorylation and its interaction with Smad2. In addition, we demonstrated that KLF4 binding to the KLF-binding elements of the TβRI promoter and formation of the KLF4-Smad2 complex to the Smad-responsive region of the promoter mediate cooperative TβRI promoter occupancy. This study outlines a novel pathway of how KLF4 is emerging as an important non-Smad protein regulator of TGF-β signaling in VSMCs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Treatment

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were sacrificed, the aorta was removed, and VSMCs were isolated as described previously (26). VSMCs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained under 5% CO2 at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere. All studies used cells from passages 3–6. Before stimulation with TGF-β1 and infection with adenoviruses, VSMCs were incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h. For inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated for 1 h with either the TβRI inhibitor SB431542 (Promega, Madison, WI), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Promega), or the ERK inhibitor PD98059 (Promega) before the addition of TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Human embryonic kidney 293A cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Adenovirus Expression Vector and Plasmid Constructs

pEGFP-KLF4 and adenovirus pAd-KLF4 were described previously (4). Expression plasmid for Smad2, pcDNA3.0-Smad2 (27), was kindly provided by Daniel J. Bernard (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). For the promoter assay, the 5′ regulatory region of TβRI (−993 to +21 bp) was amplified by PCR using the primer pairs 5′-GGTACCGAAGGTGGGTGGAGCGTCTCAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AAGCTTGGTCCCGCTGCCACTGTTTG-3′ (antisense). The PCR product was cloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) to generate the TβRI promoter-reporter pGL3-TβRI-luc. To generate additional 5′ deletion mutants, the following primers were used for PCR amplification: 5′-GGTACCGAGCGAGCAACGTCCACAGT-3′ (sense), 5′-GGTACCTGCGGGCTCCCTCGGGCG-3′ (sense), and 5′-AAGCTTGGTCCCGCTGCCACTGTTTG-3′ (antisense). To generate additional 3′ deletion mutant, the following primers were used for PCR amplification: 5′-GGTACCGAAGGTGGGTGGAGCGTCTCAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AAGCTTTTTTCTTCTACTCCAACCCCACCCT-3′ (antisense). The PCR products were then subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector, which was then used for site-directed mutagenesis.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were isolated from VSMCs as described previously (28), electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in TTBS for 2 h at 37 °C and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: 1:500 rabbit anti-SM22α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), catalog no. sc-50446), 1:500 mouse anti-SM α-actin (Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA), catalog no. ab5694), 1:500 mouse anti-PCNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-7907), 1:500 rabbit anti-KLF4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-20691), 1:500 rabbit anti-TβRI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-398), 1:1000 rabbit antiphospho-Smad2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA), catalog no. 3101, Ser465/467), 1:1000 rabbit anti-Smad2 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 3103), 1:1000 rabbit antiphospho-Smad3 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9520, Ser423/425), 1:1000 rabbit anti-Smad3 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9523), 1:1000 rabbit antiphospho-p38 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9216, Ser180/182), 1:1000 rabbit anti-p38 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9217), 1:500 mouse anti-ERK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-135900), 1:500 mouse antiphospho-ERK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-81492, Thr202/Tyr204), and 1:1000 mouse anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-47778). After incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody, antibody-antigen complexes were revealed using the Chemiluminescence Plus Western blot analysis kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting Analysis

VSMCs were prepared for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of cell cycle distribution. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105/well and incubated at 37 °C. The following day, cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml). Cells were harvested by trypsinization and fixed in 70% ethanol. Thirty minutes before fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, the cells were stained with propidium iodide.

RNA Isolation and Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription- PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as described previously (29). The following primer pairs were used for the determination of KLF4, TβRI, and KLF5 gene expression, respectively: 5′-GGCTGATGGGCAAGTTTGTG-3′ and 5′-CAAGTGTGGGTGGCTGTTCT-3′, 5′-TCCCCGAGACAGGCCATTTG-3′ and 5′-TCCGACACCAACCACAGCTGAG-3′, and 5′-CTTCATCTCTCGGTCCCTTC-3′ and 5′-CGGGTTACTCCTTCTGTTGT-3′. The oligonucleotides 5′-CAGGGTGTGATGGTGGG-3′ and 5′-GGAAGAGGATGCGGCAG-3′ were used for the determination of β-actin gene expression (used as the internal control). The PCR conditions were 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s.

Small Interfering RNA Transfection

Small interfering RNA targeting KLF4 and KLF5 were synthesized by Sigma, as described previously (15, 30). siRNAs against the rat sequences for TβRI (accession number NM_012775), p38α (accession number NM_031020), Smad2 (accession number NM_019191), and Smad3 (accession number NM_013095) were designed and synthesized by Sigma. The siRNA sequences used were as follows: TβRI siRNA, 5′-GACAAAGUUAUACACAAUAtt-3′ and 5′-UAUUGUGUAUAACUUUGUCtt-3′; p38α siRNA, 5′-CAUUCAAGUGCCUCUUGUUtt-3′ and 5′-AACAAGAGGCACUUGAAUGtt-3′; Smad2 siRNA, 5′-CGAAUGUGCACCAUAAGAAtt-3′ and 5′-UUCUUAUGGUGCACAUUCGtt-3′; Smad3 siRNA, 5′-GGAAUUUGCUGCCCUCCUAtt-3′ and 5′-UAGGAGGGCAGCAAAUUCCtt-3′. As a nonspecific control siRNA, scrambled siRNA duplex was used. Transfection was done using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection was performed for 24 h, and the medium was then changed to fresh Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% fetal calf serum for a further 24 h. Cells were then treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml). At the end of each experiment, knockdown of respective proteins was assessed by Western immunoblotting.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assay

Co-immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (31, 32). Briefly, cell extracts were first precleared with 25 μl of protein A-agarose (50%, v/v). The supernatants were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-phosphoserine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog no. sc-81514), anti-KLF4, or anti-TβRI antibodies for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with protein A-agarose overnight at 4 °C. Protein A-agarose-antigen-antibody complexes were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 60 s at 4 °C. The pellets were washed five times with 1 ml of IPH buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 20 min each time at 4 °C. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting with the anti-KLF4, anti-TβRI, or anti-Smad2 antibodies. The experiments were replicated at least three times.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies-Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers used to generate a mutation in the putative KLF4-binding site 1 were 5′-GACTGTGCAGGGAAAGTCAGGGAGGGGTTGGAGTAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTACTCCAACCCCTCCCTGACTTTCCCTGCACAGTC-3′ (antisense); primers for mutation in the KLF4-binding site 2 were 5′-ACTCTTACGGGCACTCCCAGCGCTTAGTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GACTAAGCGCTGGGAGTGCCCGTAAGAGT-3′ (antisense); and primers for mutation in the KLF4-binding site 3 were 5′-ACCCTGCCCCCTCCCGCCGGTAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTACCGGCGGGAGGGGGCAGGGT-3′ (antisense). All constructs were verified by sequencing the inserts and flanking regions of the plasmids. Serine-to-alanine mutations of KLF4 at Ser415 (S415A), Ser444 (S444A), and Ser470 (S470A) were carried out with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as described previously (4). Each mutation was verified by DNA sequence analysis.

Luciferase Assay for TβRI Promoter Activity

Human embryonic kidney 293A cells were maintained as described previously (4). 3 × 104 cells were seeded in each well of a 24-well plate and grown for 24 h prior to transfection with reporter plasmids under study and the control pTK-RL plasmid. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase assays were performed 24 h later using a dual luciferase assay kit (Promega). Specific promoter activity was expressed as the relative activity ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase. All promoter constructs were evaluated in a minimum of three separate wells per experiment.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The ChIP assay was carried out essentially as described previously (32). Briefly, VSMCs were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min to cross-link proteins with DNA. The cross-linked chromatin was then prepared and sonicated to an average size of 400–600 bp. The DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated overnight with the anti-KLF4 or anti-Smad2 antibodies. After reversal of cross-linking, the genomic region of the TβRI flanking the potential Smad-binding sites (the region between −806 and −561) was amplified by PCR with the following primer pairs: 5′-CCACGCGGGGTCAGGAAGGT-3′ (sense, designated as P1-F) and 5′-CTCCCTAGACCCGCTCCTCAATTC-3′ (antisense, designated as P1-R). The genomic region of the TβRI flanking the potential KLF4-binding sites (the region between −483 and −241) was amplified by PCR with the following primer pairs: 5′-AGGGAAAGTCAGGGTGGGGTT-3′ (sense, designated as P2-F) and 5′-CTCTAACCACGCCTCCGCACT-3′ (antisense, designated as P2-R). Sequential two-step ChIP assays were performed as described previously (33). In brief, chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated by incubating overnight with anti-KLF4 antibody or with IgG as negative control. After several washes, the precipitates were incubated with 50 μl of buffer containing 0.5% SDS and 0.1 m NaHCO3 for 10 min at 65 °C. The supernatant was collected after spinning; diluted with 1 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate; and incubated with anti-Smad2 antibody overnight. After washing, the protein-DNA complexes were eluted from the beads and treated with proteinase K overnight. DNA was purified with a minicolumn, and the Smad-binding region of the TβRI promoter was amplified by PCR using the Smad-binding region-specific primers (P1-F and P1-R).

DNA Affinity Precipitation Assay

The oligonucleotides containing biotin on the 5′-end of the each strand were used. The sequences of these oligonucleotides are as follows: the KLF4-binding site 2, biotin-5′-ACTCTTACGGGCACACCCAGCGCTTAGTC-3′ (forward) and biotin-5′-GACTAAGCGCTGGGTGTGCCCGTAAGAG-3′ (reverse), which corresponds to −420/−392 bp of the TβRI promoter region; the KLF4-binding site 3, biotin-5′-GCTGGACCCTGCCCCCACCCGCCGGTAGAGTA-3′ (forward) and biotin-5′-TACTCTACCGGCGGGAGGGGGCAGGGTCCAGC-3′ (reverse), which corresponds to −363/−332 bp of the TβRI promoter region. Each pair of oligonucleotides was annealed following standard protocols. VSMCs treated with or without 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 40 min were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40) containing protease inhibitors. Whole-cell extracts (100 μg) were precleared with ImmunoPure streptavidin-agarose beads (20 μl/sample; Promega) for 1 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation for 2 min at 12,000 rpm, the supernatant was incubated with 100 pmol of biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides and 10 μg of poly(dI-dC)·poly(dI-dC) overnight at 4 °C with gentle rocking. Then 30 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads was added, followed by a further 1 h of incubation at 4 °C. The protein-DNA-streptavidin-agarose complex was washed four times with lysis buffer, separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE, and subjected to Western blotting with different antibodies.

Statistical Analysis

Data presented as bar graphs are the means ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

TGF-β1 Increases Expression of Smooth Muscle Cell Marker Genes and Attenuates Cell Cycle Progression in VSMCs

TGF-β1 treatment of VSMCs either stimulates proliferation (34, 35) or induces differentiation (14, 20, 36), depending on the experimental conditions. Using cultured rat VSMCs, we first examined the effect of TGF-β1 on the expression of two VSMC differentiation markers, SM22α and SM α-actin, and the cell cycle progression. Treatment with TGF-β1 increased expression of SM22α and SM α-actin while decreasing the PCNA levels in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1, A and B). Cell cycle analysis showed that the G0/G1 cell population was increased to 42% after TGF-β1 treatment for 48 h, with only 15% of untreated cells being arrested in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 1C). In addition, there was a reduction in cell proportion in S phase and G2/M phase after TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. 1C). These findings suggest that TGF-β1 inhibits cell cycle progression and induces differentiation in VSMCs.

FIGURE 1.

TGF-β1 affects expression of smooth muscle cell marker genes and cell cycle progression. A, cultured rat VSMCs were serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for the indicated times. B, alternatively, serum-starved VSMCs were treated for 48 h without or with 4 ng/ml TGF-β1. Total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for SM22α, SM α-actin, and PCNA. Actin was included as a loading control. Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities that were measured and normalized to β-actin are shown on the right. C, synchronized VSMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide, and the cell cycle phase was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 h). D, VSMCs were transfected with siRNA targeting TβRI (TβRI-siRNA) or non-silencing control siRNA (NS-siRNA) for 48 h. Cells were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h, and then total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for SM22α, SM α-actin, PCNA, and TβRI expression. β-Actin was included as a loading control. Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities that were measured are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus the non-silencing siRNA group.

RNA interference was used to silence the expression of TβRI and to assess its effects on TGF-β1-induced VSMC differentiation. Off-target activity of the rat-specific TβRI siRNA was examined using a non-silencing control siRNA. Measurements of protein expression showed that the targeted TβRI siRNA knocked down between 75 and 80% of cellular TβRI that was induced by TGF-β1; the non-silencing control siRNA had no impact on the expression of TβRI (Fig. 1D). Transfection with TβRI siRNA reduced SM22α and SM α-actin protein levels while up-regulating PCNA expression in TGF-β1-treated cells. These results are consistent with the conclusion that TβRI expression is closely linked to VSMC differentiation by TGF-β1.

KLF4 Mediates TGF-β1-induced TβRI Expression in VSMCs

To confirm that KLF4 and TGF-β1 are involved in the regulation of VSMC differentiation, we examined the effect of TGF-β1 on KLF4 protein expression by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). As anticipated, TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) time-dependently induced KLF4 levels, reaching a maximum after 6 h before returning to basal levels by 48 h of treatment with TGF-β1. A similar pattern of TβRI expression following TGF-β1 stimulation was observed (Fig. 2A). Measurements of mRNA levels by semiquantitative RT-PCR showed comparable changes in KLF4 and TβRI expression in response to TGF-β1 (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of KLF4 on TGF-β1-induced TβRI expression. A, serum-starved VSMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for KLF4 and TβRI. B, total RNA was extracted from VSMCs treated with TGF-β1 as described above and analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Data represent relative KLF4 and TβRI transcript expression normalized to β-actin mRNA. Error bars, mean values ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus 0 h group. C, VSMCs were transfected with siRNA targeting KLF4, KLF5, or a non-silencing control siRNA (NS-siRNA) for 48 h. Cells were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h, and then total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for TβRI, SM22α, SM α-actin, KLF5, and KLF4 expression. D, transfected as in C, VSMCs were then treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 12 h, followed by total RNA extraction and analysis by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Data represent relative TβRI, KLF5, and KLF4 transcript expression normalized to β-actin mRNA. Error bars, mean values ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus TGF-β1 group. E, VSMCs were infected with pAd or pAd-KLF4 for 24 and 48 h. Total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for TβRI, SM22α, SM α-actin, and KLF4 expression. F, VSMCs were infected as in E, after which total RNA was extracted and analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Data represent relative TβRI and KLF4 transcript expression normalized to β-actin mRNA. Error bars, mean values ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus the pAd group. G, VSMCs were transfected with siRNA targeting Smad2, Smad3, or non-silencing siRNA for 48 h. Cells were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h, and then total protein lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for TβRI, Smad2, and Smad3. In each Western blot analysis, β-actin was used as a loading control.

Transfection of VSMCs with KLF4 siRNA resulted in the suppression of TβRI mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2, C and D). Correspondingly, we observed a reduction in TGF-β1-induced expression of SM22α and SM α-actin proteins in response to KLF4 silencing, whereas knockdown of KLF5 had no detectable effect on the expression of these differentiation markers (Fig. 2C) or on TβRI mRNA levels (Fig. 2D). Conversely, overexpression of KLF4 markedly induced expression of TβRI, SM22α, and SM α-actin (Fig. 2, E and F). These results clearly suggest that TGF-β1 induces the expression of KLF4 and TβRI and that KLF4 has a key role in TβRI up-regulation by TGF-β1.

Smads are central mediators of TβR signals, so we determined whether TGF-β1-dependent induction of TβRI levels is influenced by inhibition of Smad 2 and/or Smad3. VSMCs were incubated either with siRNA targeting Smad2, Smad3, or the combination Smad2 and Smad3 for 72 h. Knockdown of Smad2 and Smad3 was selective and resulted in ∼70% reduction in their respective protein levels (Fig. 2G). Silencing of either Smad2 or Smad3 markedly suppressed TβRI up-regulation by TGF-β1, demonstrating that TGF-β1/KLF4 signaling induces TβRI through Smad.

TGF-β1 Induces KLF4 Phosphorylation via Smad and p38 MAPK Signaling in VSMCs

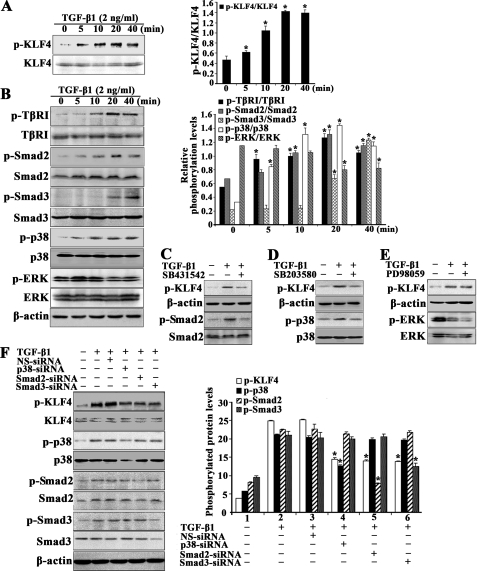

The potential role of KLF4 in TGF-β1 signaling and function was investigated by determining KLF4 phosphorylation in VSMCs in response to TGF-β1. This experiment showed that TGF-β1 increased phosphorylation of KLF4 within 5 min, reaching a maximum between 20 and 40 min (Fig. 3A). Under these experimental conditions, the phosphorylation of TβRI, Smad2, Smad3, and p38 MAPK increased concurrently in a time-dependent manner, whereas ERK phosphorylation was negatively affected by TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B). The level of expression of these molecules was not affected over the time course study (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

TGF-β1 induces KLF4 phosphorylation via Smad and p38 MAPK signaling. A, cultured VSMCs were treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 0–40 min. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphoserine antibody and analyzed by Western blot for KLF4 (top). Total protein lysates were also immunoblotted for total KLF4 expression (bottom). Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities that were measured and normalized to total KLF4 are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). B, cultured VSMCs were treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 0–40 min. Aliquots of the cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphoserine antibody and analyzed by Western blot for TβRI (top). Total protein lysates were also immunoblotted for TβRI as well as the total and phosphorylated forms of Smad2, Smad3, p38, and ERK. Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities of phosphorylated molecules normalized to their total counterpart are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). C–E, VSMCs were pretreated either with SB431542 (10 μm), SB203580 (20 μm), or PD98059 (20 μm) for 1 h, followed by a 40-min incubation with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml). Total protein lysates were collected, and aliquots were used for the detection of phosphorylated KLF4 in anti-phosphoserine immunoprecipitates. Other aliquots of protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for phosphorylated and total forms of Smad2, p38, and ERK. F, VSMCs were transfected with siRNA targeting p38, Smad2, or Smad3 or non-silencing control siRNA (NS-siRNA) for 48 h. Cells were then treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min, after which the phosphorylated and total forms of KLF4, p38, Smad2, and Smad3 were determined as described above. Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities of phosphorylated molecules are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus the non-silencing siRNA group. B–F, β-actin was used as a loading control.

Experiments were then conducted to assess the importance of Smad and p38 MAPK signaling in promoting KLF4 phosphorylation by TGF-β1. VSMCs were incubated either with the TβRI inhibitor, SB431542, the p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, or the ERK inhibitor, PD98059, for 1 h before exposure to TGF-β1. Pharmacological inhibition of TβRI or p38 MAPK blocked TGF-β1-induced KLF4 phosphorylation, whereas ERK inhibition had no detectable effect (Fig. 3, C–E). To independently confirm these observations, cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Smad2, Smad3, or p38α MAPK and then incubated with TGF-β1 for 40 min (Fig. 3F). Under these conditions, inducible KLF4 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 was blocked, which correlated with a decrease in the levels of phosphoactive and total forms of Smad2, Smad3, or p38α (Fig. 3F). Together, these results suggest that Smad and p38 MAPK pathways mediate the TGF-β1-induced KLF4 phosphorylation in VSMCs.

TGF-β1-inducible Interaction of KLF4 with Smad2/3 Requires KLF4 Phosphorylation

KLF4 has been found to interact with Smad3 in myofibroblasts (23, 37). Because TGF-β1 induced KLF4 phosphorylation, experiments were conducted to determine whether KLF4 phosphorylation affected its ability to interact with Smad2 or Smad3 in VSMCs. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were carried out, and we found that TGF-β1 time-dependently increased the levels of Smad2 and Smad3 present in anti-KLF4 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4A). Likewise, reciprocal immunoprecipitation with anti-Smad2 showed temporal co-sedimentation of KLF4 in response to TGF-β1. Pharmacological inhibition of TβRI and p38 MAPK suppressed TGF-β1-dependent recruitment of KLF4 with Smad2 and Smad3 (Fig. 4B). Correspondingly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of p38α MAPK was accompanied by marked reduction in KLF4 complexed with Smad2/3 when compared with the non-silencing control siRNA (Fig. 4C). As anticipated, knockdown of Smad2 or Smad3 also decreased their interaction with KLF4 in TGF-β1-treated cells (Fig. 4C). These results clearly indicate the role of KLF4 phosphorylation in promoting its association with Smad2/3.

FIGURE 4.

KLF4 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 increases the interaction between KLF4 and Smad2/3. A, cultured VSMCs were treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 0–40 min. Cells were lysed, and anti-KLF4 immunoprecipitates (IP) were then analyzed by Western blot (IB) for Smad2 and Smad3 co-sedimentation. Likewise, anti-Smad2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting for KLF4 co-sedimentation. IgG was used as negative control (Neg) for immunoprecipitation. B, VSMCs were pretreated for 1 h with either the TβRI inhibitor SB431542 (10 μm), p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (20 μm), or ERK inhibitor PD98059 (20 μm) and then stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min. The interaction between KLF4, Smad2, and Smad3 was assessed as described above. C, VSMCs were transfected with siRNA targeting p38, Smad2, or Smad3 or non-silencing control siRNA (NS-siRNA) for 48 h. Cells were then stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min, followed by the analysis of Smad2 and Smad3 co-sedimentation in anti-KLF4 immunoprecipitates. *, nonspecific band representing IgG. D, VSMCs were transfected for 48 h with expression vectors encoding either EGFP-KLF4 wild type (WT) or its phosphorylation-deficient mutants, S415A, S444A, or S470A. Cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min, after which the phosphorylated and total forms of KLF4 and its interaction with Smad2 and Smad3 were determined as described above.

Point mutation experiments were conducted to verify that the KLF4-Smad interaction is elicited by KLF4 phosphorylation. VSMCs were transfected with either KLF4 wild type or KLF4 with a single Ser-Ala point mutation within the DNA-binding domain at position 415, 444, or 470. Immunoblot analysis with phospho-KLF4 antibody showed that the S470A substitution markedly reduced TGF-β1-dependent KLF4 phosphorylation; this was accompanied by impaired co-sedimentation with Smad2/3 (Fig. 4D). In contrast, S415A and S444A point mutations had no detectable effect on the extent of KLF4 phosphorylation and association with Smad 2/3 when compared against KLF4 wild type in response to TGF-β1 (Fig. 4D). Thus, phosphorylation at Ser470 is necessary for the interaction of KLF4 with Smad2/3.

KLF4 and Smad2 Cooperatively Activate the TβRI Promoter

After having demonstrated that KLF4 mediates TGF-β1-induced TβRI expression through interaction with Smad2/3 (Figs. 2 and 4A), we then examined whether KLF4-Smad2 association plays a role in the activation of the TβRI promoter. HEK293A cells were transfected with a TβRI promoter-reporter plasmid and increasing amounts of KLF4 or Smad2 expression plasmids. Measurements of luciferase activity showed that overexpression of KLF4 or Smad2 dose-dependently increased by severalfold the transcriptional activity of TβRI when compared with control plasmids (Fig. 5, A and B), whereas cotransfection with KLF4 and Smad2 expression plasmids induced an ∼19-fold increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that KLF4 and Smad2 might exert an additive effect on the transcriptional activation of TβRI. Indeed, knockdown of Smad2 with siRNA abolished the additive effect in cells cotransfected with Smad2 and KLF4 expression plasmids (Fig. 5D, compare lane 3 versus lane 4 and lane 6 versus lane 7). Moreover, a further induction in TβRI promoter activity was observed when the cotransfected cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 (Fig. 5E, lane 3 versus lane 2). Pretreatment with the TβRI inhibitor SB431542, the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, or a combination of both significantly reduced the reporter gene activity in the TGF-β1-treated 293A cotransfected cells (Fig. 5E).

FIGURE 5.

KLF4 and Smad2 cooperatively activate the TβRI promoter. A–C, 293A cells were co-transfected for 24 h with pGL3-TβRI-luc and either pEGFP-KLF4 or pcDNA3.0-Smad2 added alone or in combination (C). Empty vectors were used to normalize plasmid load in each dish. Cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured using the dual luciferase reporter assay system. Data represent relative TβRI promoter activity normalized to Renilla luciferase. Error bars, means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus pEGFP-N1 or pcDNA3.0 group. Shown in the lower portion of each panel are immunoblots from total cell lysates to confirm overexpression of targeted proteins. D, 293A cells were co-transfected as in C in the presence of 25 pmol of siRNA targeting Smad2 or non-silencing control siRNA (NS-siRNA) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured on total cell lysates as described above. *, p < 0.05 versus the Smad2 siRNA group. E, 293A cells were co-transfected as in C for 24 h and then stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min in the presence or absence of SB431542 (10 μm) and/or SB203580 (20 μm). Luciferase activity was determined as described above. *, p < 0.05 versus untreated group (no TGF-β1); #, p < 0.05 versus TGF-β1-treated group.

KLF4 Binds Directly to the TβRI Promoter

Using the TESS computational program, we established that the −472/−339 bp region of the rat TβRI promoter contains two typical KLF4-binding sites (CACCC) and one with a reverse orientation sequence (GGGTG) (Fig. 6A). ChIP assays were performed to test whether KLF4 interacts directly to these putative KLF4-binding sites in VSMCs. Constitutive KLF4 binding was detected on the TβRI promoter, whereas no obvious signal was observed when chromatin samples were precipitated with a control mouse IgG (Fig. 6B). The TGF-β1 treatment recruited more KLF4 protein to the DNA as compared with untreated cells. These results suggest that KLF4 specifically interacts with TGF-β1-responsive sites of the TβRI promoter. We further investigated whether ectopically expressed KLF4 could bind to the TβRI promoter. Infection of VSMCs with pAd-KLF4 greatly increased KLF4-TβRI promoter interaction when compared with pAd-GFP-infected VSMCs (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

KLF4 binds directly to the TβRI promoter. A, schematic representation of the KLF4-binding sites (5′-CACCC-3′) in the TβRI promoter region and primers used for amplification of the TβRI promoter for ChIP assays. B, VSMCs were exposed to vehicle or TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min; then cross-linked chromatin was extracted and immunoprecipitated with an anti-KLF4 antibody. Nonimmune IgG was used as negative control for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using rat TβRI promoter-specific primers (P2-F and P2-R). PCR products from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). C, VSMCs were infected with control pAd-GFP vector or pAd-KLF4, and a ChIP assay was performed as described above. D, 293A cells were co-transfected with KLF4 expression vector and the TβRI promoter-reporter plasmid containing various 5′ deletion mutants with (☆) or without site-directed inactivation of KLF4-binding sites. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared for the luciferase assay. Data represent relative TβRI promoter activity normalized to Renilla luciferase. Error bars, means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus pTβRI/−993; #, p < 0.05 versus intact KLF4-binding site mutants. E, oligonucleotide pull-down assay was performed with consensus KLF4-binding site 2 or 3 biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides as probes. The binding reaction was performed with total cell extracts from VSMCs treated with or without TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min. DNA-bound proteins were collected with streptavidin-agarose beads and analyzed by Western blot for KLF4 or Smad2. Blots from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities of DNA-bound proteins are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min).

There are three KLF4-binding sites in the proximal region of the TβRI promoter (Fig. 6A). To determine which DNA elements are involved in the KLF4 induction of TβRI, a series of 5′-deletion mutants and KLF4-binding site mutants were tested in 293A cells co-transfected with pEGFP-KLF4. pTβRI/−993 and pTβRI/−453 did not significantly modify the transcriptional induction by KLF4 (Fig. 6D). pTβRI/−386 reduced by 50% the transcriptional response of KLF4 (Fig. 6D), whereas pTβRIs with more extensive deletions were not activated by KLF4 (data not shown). These data suggested that the KLF4-responsive elements are located in the −453/+21 region in the TβRI promoter. To test the role of these putative KLF4-binding sites in TβRI induction by KLF4, reporter plasmids containing the TβRI promoter with site-specific mutations were analyzed (Fig. 6D). Disruption of KLF4-binding site 1 (−472/−468 bp region) did not affect the transcriptional induction by KLF4, whereas disruption of site 2 (−402/−398 bp region) or 3 (−343/−339 bp region) reduced significantly the transcriptional response of KLF4.

To verify the binding activities of the KLF4-binding sites 2 and 3, we analyzed crude cell extracts of VSMCs incubated with biotin-labeled oligonucleotides corresponding to each of the two KLF4-binding sites in pull-down assays (Fig. 6E). The same pattern of KLF4 protein bands was observed with both oligonucleotide probes. Extracts from cells treated with TGF-β1 showed stronger KLF4 binding to the two probes by ∼2-fold, in agreement with the ChIP data (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, such binding was specific because Smad2 interaction could not be detected.

Interaction of KLF4 with Smad2 Bound to the Smad-binding Element Provides Cooperative Activation of the TβRI Promoter

Because Smad2 could activate the TβRI promoter (Fig. 5B), we performed ChIP assays to determine whether Smad2 binds directly to this promoter. Constitutive Smad2 binding was detected on the TβRI promoter, whereas no obvious signal was observed when chromatin samples were precipitated with a control mouse IgG (Fig. 7A). The TGF-β1 treatment increased Smad2 binding by ∼2.2-fold to the putative Smad-binding region as compared with untreated cells. To define which DNA elements are involved in the Smad2 induction of TβRI, a series of 5′-deletion mutants were tested in 293 cells co-transfected with pcDNA-Smad2. pTβRI/−993 elicited a strong transcriptional response by Smad2, whereas pTβRI/−453 and pTβRI/−386 were unresponsive to Smad2 (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that the Smad-responsive element is located in the −993/−453 region in the TβRI promoter.

FIGURE 7.

Presence of the KLF4-Smad2 complex in the Smad-responsive region of the TβRI promoter. A, VSMCs were treated with or without TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 40 min; then cross-linked chromatin was extracted and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Smad2 antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using rat TβRI promoter-specific primers (P1-F and P1-R). Nonimmune mouse IgG was used as negative control for immunoprecipitation (IP). PCR products from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). B, 293A cells were co-transfected with Smad2 expression vector and the TβRI promoter-reporter plasmid containing 5′ deletion mutants (pTβRI/−453 and pTβRI/−386) or not (pTβRI/−993). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared for the luciferase assay. Data represent relative TβRI promoter activity normalized to Renilla luciferase. Error bars, means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus pTβRI/−993. C, cross-linked chromatin from control and TGF-β1-treated VSMCs was extracted and immunoprecipitated with an anti-KLF4 antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using rat TβRI promoter-specific primers (P2-F and P2-R) (top) or (P1-F and P1-R) (bottom). PCR products from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). D, cross-linked chromatin from control and TGF-β1-treated VSMCs were immunoprecipitated with an anti-KLF4 antibody, followed by a brief treatment with 0.5% SDS-containing buffer. The released material was then subject to a second immunoprecipitation with an anti-Smad2 antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using rat TβRI promoter-specific primer (P1-F and P1-R). PCR products from a representative experiment are shown on the left, whereas band intensities are shown on the right. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (0 min). E, 293A cells were co-transfected with the expression plasmids indicated together with the TβRI promoter-reporter plasmid containing or not containing a deletion in the KLF4-binding region (Δ−483/−241 bp) or Smad-binding region (Δ−806/−561 bp). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared for luciferase assay. Data represent relative TβRI promoter activity normalized to Renilla luciferase. Error bars, means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus pTβRI/−993.

Because KLF4 interaction with Smad2 (Fig. 4A) cooperatively activates the TβRI promoter (Fig. 5C), we hypothesized that KLF4 could form a stable complex with Smad2 at the KLF4-binding region, Smad-responsive element, or both of these two regions. ChIP assays were performed with two sets of PCR primers that selectively amplify either the Smad-binding region (P1-F and P1-R) or the KLF4-binding region (P2-F and P2-R) (Fig. 6A). The two regions were detected constitutively in KLF4 immunoprecipitates, and the TGF-β1 treatment increased both signals (Fig. 7C). In contrast, only the Smad-binding region was detected in Smad2 immunoprecipitates using both sets of primers (data not shown). These results are consistent with the oligonucleotide pull-down data (Fig. 6E). A two-step ChIP assay was then performed, whereby the KLF4 immunoprecipitates were subjected to a second immunoprecipitation with anti-Smad2, followed by PCR amplification with P1-F/P1-R. Under these conditions, the Smad-binding region was detected constitutively, and the TGF-β1 treatment increased the concurrent recruitment of KLF4 and Smad2 to the TβRI promoter. These results suggest that KLF4 forms a stable complex with Smad2 that is bound to the Smad-binding region of the TβRI promoter.

To further determine the role of the Smad-binding region in the cooperative transcriptional induction of TβRI by KLF4 and Smad2, 293A cells were cotransfected with pTβRI/−993, pTβRI/−993(Δ−483/−241), or pTβRI/−993(Δ−806/−561) together with empty vector or the expression vectors encoding KLF4 and Smad2. As anticipated, deletion of the −483/−241 KLF4-binding region abolished the transcriptional response of KLF4 while maintaining Smad2 responsiveness and the cooperative activation by Smad2 and KLF4 (Fig. 7E). In contrast, deletion of the −806/−561 Smad2-binding motif had no inhibitory effect on the transcriptional induction of the TβRI promoter by KLF4; however, both the Smad2 responsiveness and cooperative activation by Smad2 and KLF4 were lost (Fig. 7E). These data support a model in which the interaction of KLF4 with Smad2 bound to the Smad-binding element provides cooperative activation of the TβRI promoter in VSMCs.

DISCUSSION

TGF-β1 plays an important role in regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation (38–41). However, despite the importance of TGF-β1 in cell phenotypic modulation, little is known about the molecular mechanism by which TGF-β1 elicits its downstream effects in VSMCs. The data reported here demonstrated that KLF4, as a non-Smad protein downstream of the TβRI, cooperates with Smad to activate the TβRI promoter, describing a positive feedback mechanism by which TβRI activation by TGF-β1 induces the expression and phosphorylation of KLF4, which in turn activates the TβRI promoter (Fig. 8). This study is the first report to delineate the molecular mechanism of KLF4 action in TGF-β signaling in VSMCs, supporting the notion that KLF4 acts as a regulator to activate p38 MAPK and Smad signaling via TβRI.

FIGURE 8.

Model of KLF4-mediated TβRI expression. KLF4 expression and phosphorylation are induced by p38 MAPK and Smad signaling activated by interaction of TGF-β1 with its receptors. Direct binding of KLF4 to the TβRI promoter leads to transcriptional activation of TβRI, whereas KLF4 interaction with Smad2 prebound to the Smad-binding element promotes cooperative TβRI promoter activation. The question mark indicates that TGF-β1-mediated activation of p38 MAPK could occur via an additional membrane-bound TβRI complex.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β1 potently inhibits mouse VSMC proliferation and that its antiproliferative effect is due to G0/G1 arrest mediated primarily by the p38 MAPK pathway (42). Results in this study showed that TGF-β1 induced VSMC differentiation by activating the genetic program that induces smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes, SM22α and SM α-actin, in addition to growth inhibition of VSMCs. We found that TGF-β1-induced growth inhibition and differentiation of VSMCs were associated with the up-regulation of KLF4 and TβRI gene expression. Our recent study demonstrates that overexpression of KLF4 could up-regulate expression of differentiation marker genes and down-regulate the SMemb (15). Thus, KLF4 may have a key role in VSMC differentiation induced by TGF-β1. However, it remains unclear how KLF4 regulates TGF-β signaling in VSMCs.

The biological effects of TGF-β are mainly mediated by their receptors (i.e. TβRI and TβRII). The activation of TβRs by TGF-β can trigger the canonical Smad-mediated signaling pathway and non-Smad protein-mediated pathways, including cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (43), RhoA (36, 44), protein kinase N (20), and MAPK family (42). The activation of different signaling pathways results in distinct biological effects on different cell types. Here, we showed that TGF-β1 rapidly and strongly induced KLF4 phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner in VSMCs. Furthermore, TGF-β-induced KLF4 phosphorylation is accompanied by the increased interaction of KLF4 with Smad2 and Smad3. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Smad and the p38 MAPK pathways play an important role in regulating cellular processes, such as inflammation, cell differentiation, and apoptosis (42, 45–47). To further define the signaling pathways leading to TGF-β-induced KLF4 phosphorylation, we examined the effects of TβRI inhibitor, TβRI-siRNA, p38 inhibitor, and p38-siRNA on KLF4 phosphorylation induced by TGF-β1. Inhibition of TβRI or p38 MAPK blocked TGF-β1-induced Smad2 and KLF4 phosphorylation. Similarly, inhibition of TβRI or p38 MAPK attenuated the interaction of KLF4 with Smad2 and Smad3 (Fig. 4, B and C). These results strongly suggest that TGF-β1 induces KLF4 phosphorylation via Smad and p38 MAPK signaling, and KLF4 phosphorylation increases its interaction with Smad2 (Fig. 4D). Thus, TGF-β-induced growth inhibition and differentiation of VSMCs are mediated by KLF4 via both the Smad-dependent and p38 MAPK-dependent signaling pathways.

Based on the observation that the expression of TβRI and KLF4 genes is induced by TGF-β1 and that both proteins have the same effects on VSMC differentiation, we speculated that TβRI expression could be mediated by KLF4. As expected, gain/loss of function studies of KLF4 show that KLF4 mediates TβRI expression induced by TGF-β1. Recently, the Sp1/KLF4 family proteins have emerged as important non-Smad signaling proteins that participate in TGF-β signal transduction and, under certain circumstances, can cross-talk with Smads to achieve distinct cellular functions (24, 48). It is known that the TβRII is activated by Sp1 (49). However, it has not been determined whether KLF4 trans-activates the TβRI promoter. Based on the fact that the TβRI promoter contains two typical KLF4-binding sites and one with a reverse orientation sequence (50), we constructed TβRI promoter-reporter plasmids spanning different regions of the promoter and analyzed them for their activities (Figs. 5 and 6D) while using ChIP and oligonucleotide pull-down assays to locate biologically relevant KLF4-binding elements (Fig. 6, B, C, and E). The results indicated that KLF4 binding sites 2 and 3 are required for TβRI transcriptional activation by TGF-β1 (Fig. 6). The oligonucleotide pull-down assay showed that KLF4 binds to these two elements. Further study revealed that the TβRI promoter also contains a Smad-binding sequence and that overexpression of Smad2 enhances the TβRI promoter activity (Figs. 5B and 7B). Our results show that, in addition to KLF4, Smad2 is also involved in the transcriptional activation of TβRI by TGF-β.

Because KLF4 and Smad2 interacted with each other and TGF-β1 treatment increased their interaction, we investigated whether there is any cross-talk between KLF4 and Smad2 in the induction of TβRI expression by TGF-β1. Cooperative binding of proteins to DNA sequence usually involves one element or regions upstream of the transcription initiation site, which functionally represent composite regulatory elements (31). In this study, the −993/+21 bp region of the TβRI promoter, encompassing the Smad-binding region and the KLF4-binding sites, may exhibit similar function. KLF4 interaction with Smad2 on this composite regulatory element is important for maximal transcriptional activation of TβRI by TGF-β1 in VSMCs, as evidenced by the increased TβRI promoter activity with co-transfection of KLF4 and Smad2 (Fig. 5, C–E). Further evidence of the complex formed by KLF4 and Smad2 at the Smad-binding region is provided by the oligonucleotide pull-down results and ChIP assays (Figs. 6E and 7, C–E). Taken together, we conclude that KLF4 and Smad2 bind not only to their respective elements in the TβRI promoter but also to the Smad-binding region as a stable KLF4-Smad2 complex to cooperatively activate the TβRI promoter in TGF-β1-treated VSMCs (Fig. 8).

In summary, our results show, for the first time, that TGF-β1 induces KLF4 phosphorylation via Smad and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in VSMCs and that KLF4 interacts with Smad2 to cooperatively activate the TβRI promoter. These results describe a novel positive feedback mechanism by which the TβRI activation up-regulates the expression and phosphorylation of KLF4 to ultimately activate the TβRI and further expand the network of non-Smad transcription factors in the TGF-β pathway. Therefore, KLF4 becomes another important non-Smad protein to activate TβRI.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health, NIA, Intramural Research Program. This work is also supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30971457 and 90919035, Special Fund for Preliminary Research of Key Basic Research Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grant 2008CB517402, and Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province Grant C2008001049.

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- KLF

- Krüppel-like factor

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- SM

- smooth muscle

- RT

- reverse transcription

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Owens G. K. ( 1995) Physiol. Rev. 75, 487– 517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. ( 2004) Physiol. Rev. 84, 767– 801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wassmann S., Wassmann K., Jung A., Velten M., Knuefermann P., Petoumenos V., Becher U., Werner C., Mueller C., Nickenig G. ( 2007) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 43, 301– 307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng B., Han M., Bernier M., Zhang X. H., Meng F., Miao S. B., He M., Zhao X. M., Wen J. K. ( 2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22773– 22785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujiu K., Manabe I., Ishihara A., Oishi Y., Iwata H., Nishimura G., Shindo T., Maemura K., Kagechika H., Shudo K., Nagai R. ( 2005) Circ. Res. 97, 1132– 1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber D. S. ( 2008) Circ. Res. 102, 1448– 1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Autieri M. V. ( 2008) Circ. Res. 102, 1455– 1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi J. Y., Shin I., Arteaga C. L. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10870– 10876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida T., Kaestner K. H., Owens G. K. ( 2008) Circ. Res. 102, 1548– 1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamik A., Lin Z., Kumar A., Balcells M., Sinha S., Katz J., Feinberg M. W., Gerzsten R. E., Edelman E. R., Jain M. K. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13769– 13779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinberg M. W., Lin Z., Fisch S., Jain M. K. ( 2004) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 14, 241– 246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King K. E., Iyemere V. P., Weissberg P. L., Shanahan C. M. ( 2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11661– 11669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Sinha S., McDonald O. G., Shang Y., Hoofnagle M. H., Owens G. K. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9719– 9727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai-Kowase K., Ohshima T., Matsui H., Tanaka T., Shimizu T., Iso T., Arai M., Owens G. K., Kurabayashi M. ( 2009) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 99– 106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C., Han M., Zhao X. M., Wen J. K. ( 2008) J. Biochem. 144, 313– 321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo P., Zhao K. W., Dong X. Y., Sun X., Dong J. T. ( 2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18184– 18193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S., Lechleider R. J. ( 2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1195– 1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massagué J. ( 1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 753– 791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrana J. L., Attisano L., Wieser R., Ventura F., Massagué J. ( 1994) Nature 370, 341– 347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deaton R. A., Su C., Valencia T. G., Grant S. R. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31172– 31181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edlund S., Landström M., Heldin C. H., Aspenström P. ( 2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 902– 914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal R., Khanna A. ( 2006) Stem Cells Dev. 15, 29– 39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu B., Wu Z., Liu T., Ullenbruch M. R., Jin H., Phan S. H. ( 2007) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 78– 84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Truty M. J., Lomberk G., Fernandez-Zapico M. E., Urrutia R. ( 2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6291– 6300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boon R. A., Fledderus J. O., Volger O. L., van Wanrooij E. J., Pardali E., Weesie F., Kuiper J., Pannekoek H., ten Dijke P., Horrevoets A. J. ( 2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 532– 539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han M., Wen J. K., Zheng B., Cheng Y., Zhang C. ( 2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C50– C58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard D. J. ( 2004) Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 606– 623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X. H., Zheng B., Han M., Miao S. B., Wen J. K. ( 2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 1231– 1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng B., Han M., Wen J. K. ( 2008) Biochemistry 73, 353– 357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He M., Han M., Zheng B., Shu Y. N., Wen J. K. ( 2009) J. Biochem. 146, 683– 691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han M., Li A. Y., Meng F., Dong L. H., Zheng B., Hu H. J., Nie L., Wen J. K. ( 2009) FEBS J. 276, 1720– 1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng F., Han M., Zheng B., Wang C., Zhang R., Zhang X. H., Wen J. K. ( 2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387, 13– 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein B. E., Mikkelsen T. S., Xie X., Kamal M., Huebert D. J., Cuff J., Fry B., Meissner A., Wernig M., Plath K., Jaenisch R., Wagschal A., Feil R., Schreiber S. L., Lander E. S. ( 2006) Cell 125, 315– 326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giordano A., Romano S., Mallardo M., D'Angelillo A., Calì G., Corcione N., Ferraro P., Romano M. F. ( 2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 519– 526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai S., Hollenbeck S. T., Ryer E. J., Edlin R., Yamanouchi D., Kundi R., Wang C., Liu B., Kent K. C. ( 2009) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H540– H549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S., Crawford M., Day R. M., Briones V. R., Leader J. E., Jose P. A., Lechleider R. J. ( 2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1765– 1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botella L. M., Sanz-Rodriguez F., Komi Y., Fernandez-L A., Varela E., Garrido-Martin E. M., Narla G., Friedman S. L., Kojima S. ( 2009) Biochem. J. 419, 485– 495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamiya K., Sakakibara K., Ryer E. J., Hom R. P., Leof E. B., Kent K. C., Liu B. ( 2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3489– 3498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagna G., Ku M. M., Nguyen P. H., Neuman N. A., Davis B. N., Hata A. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37244– 37255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King-Briggs K. E., Shanahan C. M. ( 2000) Differentiation 66, 43– 48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura G., Manabe I., Tsushima K., Fujiu K., Oishi Y., Imai Y., Maemura K., Miyagishi M., Higashi Y., Kondoh H., Nagai R. ( 2006) Dev. Cell 11, 93– 104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seay U., Sedding D., Krick S., Hecker M., Seeger W., Eickelberg O. ( 2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315, 1005– 1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang H., Lee C. J., Zhang L., Sans M. D., Simeone D. M. ( 2008) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 295, G170– G178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhowmick N. A., Ghiassi M., Aakre M., Brown K., Singh V., Moses H. L. ( 2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15548– 15553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feinberg M. W., Watanabe M., Lebedeva M. A., Depina A. S., Hanai J., Mammoto T., Frederick J. P., Wang X. F., Sukhatme V. P., Jain M. K. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16388– 16393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wassmer S. C., de Souza J. B., Frère C., Candal F. J., Juhan-Vague I., Grau G. E. ( 2006) J. Immunol. 176, 1180– 1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sturrock A., Cahill B., Norman K., Huecksteadt T. P., Hill K., Sanders K., Karwande S. V., Stringham J. C., Bull D. A., Gleich M., Kennedy T. P., Hoidal J. R. ( 2006) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 290, L661– L673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kowanetz M., Lönn P., Vanlandewijck M., Kowanetz K., Heldin C. H., Moustakas A. ( 2008) J. Cell Biol. 182, 655– 662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venkatasubbarao K., Ammanamanchi S., Brattain M. G., Mimari D., Freeman J. W. ( 2001) Cancer Res. 61, 6239– 6247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji C., Casinghino S., McCarthy T. L., Centrella M. ( 1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21260– 21267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]