Abstract

Stresses increasing the load of unfolded proteins that enter the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) trigger a protective response termed the unfolded protein response (UPR). Stromal cell-derived factor2 (SDF2)-type proteins are highly conserved throughout the plant and animal kingdoms. In this study we have characterized AtSDF2 as crucial component of the UPR in Arabidopsis thaliana. Using a combination of biochemical and cell biological methods, we demonstrate that SDF2 is induced in response to ER stress conditions causing the accumulation of unfolded proteins. Transgenic reporter plants confirmed induction of SDF2 during ER stress. Under normal growth conditions SDF2 is highly expressed in fast growing, differentiating cells and meristematic tissues. The increased production of SDF2 due to ER stress and in tissues that require enhanced protein biosynthesis and secretion, and its association with the ER membrane qualifies SDF2 as a downstream target of the UPR. Determination of the SDF2 three-dimensional crystal structure at 1.95 Å resolution revealed the typical β-trefoil fold with potential carbohydrate binding sites. Hence, SDF2 might be involved in the quality control of glycoproteins. Arabidopsis sdf2 mutants display strong defects and morphological phenotypes during seedling development specifically under ER stress conditions, thus establishing that SDF2-type proteins play a key role in the UPR.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Plant, Protein Structure, X-ray Crystallography, ER-Quality Control, MIR Motif, SDF2, SDF2-like, Unfolded Protein Response

Introduction

In all eukaryotes, nascent secretory and membrane proteins synthesized at the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER)6 are translocated, potentially glycosylated, and soon begin to fold with the assistance of molecular chaperones and other folding factors. Many ER-resident proteins are folding and assembly helpers that keep back the newly synthesized proteins in the ER until the correct conformations have been reached. Once nascent proteins fail to fold or assemble properly they accumulate in the ER. This increase of misfolded proteins is perceived as ER stress, triggering a complex protective response, termed the unfolded protein response (UPR) (1, 2).

UPR is conserved in eukaryotic organisms. Studies in animals have revealed that induction of the UPR is mediated through the transmembrane kinase, inositol-requiring enzyme-1 (IRE1α/IRE1β) and other sensors, namely activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) (3). The ER luminal domains of IRE1α/IRE1β, ATF6, and PERK, interact with an abundant ER chaperone of the Hsp70 family, the immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein (BiP) and form inactive sensor complexes. When unfolded proteins begin to accumulate within the ER, BiP is released. As a result, all three sensors enhance the expression of UPR target genes, including genes encoding ER chaperones and other folding helpers to increase overall protein folding and assembly efficiencies within the ER (2, 3). Moreover, PERK activity attenuates translation to adapt the secretory pathway to ER loading. UPR further induces ER-associated protein degradation to dispose of misfolded proteins, and when all other measures fail, apoptotic cell death is activated (2, 3).

In all eukaryotes, the most prominent phenomenon induced by the UPR is the transcriptional induction of ER chaperone and protein-folding genes (1, 4). ER chaperones and protein-folding proteins can be grouped in different classes according to their specificity (1). The N-glycan-dependent quality control mechanism of glycoprotein folding, also referred to as calnexin/calreticulin cycle, depends on the presence of both monoglucosylated N-linked glycans and unfolded regions in nascent glycoproteins (5). The second major ER chaperone system depends on the presence of unfolded regions in proteins containing hydrophobic residues, which are recognized by BiP (1). In mammalian cells, BiP can associate with several ER-proteins including stromal cell-derived factor2-like1 (SDF2L1) to form a large ER-localized multiprotein complex suggesting an ER network of chaperones and folding enzymes (6). Whereas the molecular functions of most factors are well characterized, SDF2L1 presents a remarkable exception. SDF2L1 and its homolog SDF2 have been identified in mouse and humans (7, 8). Fukuda et al. (7) found that SDF2L1 was up-regulated following treatment with compounds that interfere with ER homeostasis. These include A23187, a calcium ionophore, and tunicamycin, an inhibitor of protein N-glycosylation. Mouse SDF2L1 associates in vitro with BiP, the Hsp40 ERj3p and other folding enzymes even in the absence of high amounts of misfolded proteins (6, 9). However in mammals it is not known whether SDF2L1 is crucial for ER quality control and the UPR in vivo because no corresponding mutants have been described.

SDF2-type proteins are conserved in the animal and plant kingdoms. Recently it was shown that loss of the SDF2L1 homologue from Arabidopsis thaliana results in ER retention and degradation of the surface-exposed leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase EFR (10) suggesting a conserved role of SDF2-type proteins in ER protein quality control of animals and plants. Here we demonstrate that Arabidopsis SDF2 is a crucial target of the plant UPR in vivo and present the three-dimensional crystal structure providing insights into the molecular function of the protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 was used as wild-type line. T-DNA insertion lines SALK_141321 (sdf2-2), SALK_077481 (sdf2-6), and WiscDsLox293–296invI23 (sdf2-5) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (University of Nottingham, UK). Seeds were germinated on agar plates containing Murashige and Skoog salts (MS), 1% sucrose, 10 mm MES, pH 5.7, 0.8% (w/v) agar, after stratification at 4 °C for 2 days.

Transcript Analysis

Seedlings grown for 6 days on MS medium were transferred to liquid MS medium. After 24 h 10 mm DTT was added and seedlings incubated for 5 h. Total RNA was extracted (RNeasy kit; Qiagen) and 0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed (iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit; Bio-Rad). For semi-quantitative PCR, 4 μl of 5 times dilution of cDNA was used with a total reaction volume of 20 μl. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with the iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system and iQ Sybergreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Data were analyzed using the relative standard curve method, and the level of SDF2 transcripts was normalized to reference transcripts of PP2A. Primer sequences and PCR conditions used are summarized in supplemental Table S1.

Plasmid Construction

Sequences of primers are available upon request. Plasmid pAS65: a sequence containing 3×HA-epitope was amplified from pSB56 using the primers 875 and 876. The PCR product was cut with NcoI/XbaI and cloned into pAmy. Plasmid pAS66: the SDF2 coding sequence was amplified by PCR using primers 877 and 878. The resulting 671-bp fragment was cut with NcoI/SmaI and cloned into pAS65. Plasmid pAS76 (CaMV 35S:SDF2-HA): A 939-bp sequence was amplified from plasmid pAS66 with primers 970 and 883. The resulting fragment was cloned into pBinAR cut with XbaI. Plasmid pAS64 (ProSDF2:GUS): 2.47 kb of the 5′ upstream promoter sequence of SDF2 was amplified with primers 812 and 813. The resulting fragment was cloned into pBGWFS7 using the Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen).

Transgenic Plants and Ecotopic Expression

pAS64 was transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1. Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 was transformed using the floral dip method (11). A. tumefaciens mediated transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells was done according to Ref. 12.

Subcellular Localization of SDF2

Microsomal membranes of plant materials were prepared as described (13) using extraction buffer (50 mm HEPES, 10 mm KCl, 0.5% polyvinylpyrolidone 40, 10% sucrose, and a mix of protease inhibitors (Sigma)) containing 5 mm MgCl2 or 5 mm EDTA. For sucrose density gradient centrifugation microsomal membranes were fractionated on a 10.2-ml linear sucrose gradient (20–50% (w/v) in extraction buffer) at 200,000 × g for 15 h at 4 °C. Fractions (850 μl) were collected from the top and proteins were recovered by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid. To analyze membrane association, microsomal membranes were suspended in extraction buffer containing 0.5 mm KCl or 1% Triton X-100 and incubated at 4 °C for 20 min. Supernatant and pellet fractions were separated by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C.

Protoplast Fractionation

Preparation and electroporation of tobacco leaf protoplasts was carried out according to Ref. 14. Preparation of cytosol (S1), 16,000 × g supernatant containing microsomal contents (S2), and a 16,000 × g total membrane pellet (P) was performed as described in Ref. 15.

Antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against SDF2 (Ser-24 to Lys-218) fused to GST (16) at Pineda Antikörper Service (Berlin, Germany). SDF2 antibodies (1:1000), polyclonal anti-calnexin (1:5000; gift of P. Pimpl), anti-calreticulin (1:2000; gift of P. Pimpl), anti-PMA2 (1:10000; gift of M. Boutry), anti-VHA-c (1:2000, gift of K. Schumacher), and monoclonal anti-HA antibodies (1:5000; Covance) were used for immunoblot analyses. Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse (both 1:5000; Sigma) were used as secondary antibodies. Immunoreactivity was visualized using Pierce SuperSignal West Pico substrate (Thermo Fischer).

Immunogold Electron Microscopy

Root tips from six-day-old seedlings were high pressure frozen as given in Ref. 14. Freeze substitution was performed as described in supplemental Fig. S6.

Histochemical Localization of GUS Activity

In situ GUS staining was performed according to Ref. 17.

Structure Determination and Refinement of SDF2

Cloning, expression, purification, and crystallization of SDF2 as well as x-ray data collection were performed as described elsewhere (16). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using the program MOLREP (18) with PDB entry 1t9f as a search model. The sequence identity between search model and SDF2 is 37%. Iterative model building and refinement were carried out with the programs COOT (19) and REFMAC5 cycled with ARP/wARP (18) for automated water building. The final model was validated with program MOLPROBITY (20). The data collection and structural refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 3MAL.

TABLE 1.

Refinement statistics of the SDF2 structure

X-ray data collection was performed as described elsewhere (16).

| Rfactora /Rfreeb (%) | 16.7/21.2 |

|---|---|

| Content of the asymmetric unit | |

| Residues | 181 (chain A)c |

| 181 (chain B)c | |

| Water | 260 |

| Ligands | 3 Ethylene glycol molecules |

| Ions | 3 Sulfate ions |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein main/side chain | 12.31/14.05 |

| Water | 24.13 |

| R.m.s. deviation | |

| Bonds lengths (Å) | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.51 |

| Ramachandran plot analysis | |

| Favored (%) | 96.6 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.0 |

a R = Σ||Fobs(h)| − k|Fcalc(h)||/Σ|Fobs(h)| with k, a scaling factor.

b Rfree was calculated as for Rfactor but from a test set constituted by 5% of the total number of reflections randomly selected.

c In both chains, no electron density was observed for the first 12 and the last 3 amino acids.

RESULTS

To analyze whether SDF2-type proteins play a functional role in the UPR, Arabidopsis is an ideal model system because the principal mechanisms of the UPR are conserved between metazoa and plants (2), and Arabidopsis contains only one gene of the SDF2-type (AtSDF2; At2g25110). Sequence analysis of a full-length cDNA clone (U14608) confirmed the predicted structure of 6 exons and 5 introns (GenBankTM accession number NM_128068). The corresponding 218-residue long SDF2 protein shares 55 and 52% overall amino acid sequence similarity with murine/human SDF2 and SDF2L1, respectively.

SDF2 Expression Displays a Similar Induction Pattern as Known UPR Transcripts

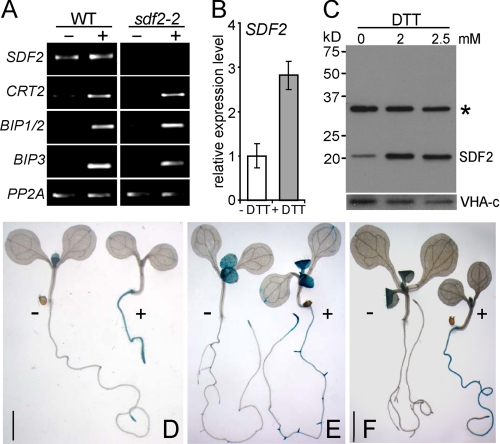

To test the role of SDF2 in the plant UPR we analyzed gene expression in Arabidopsis under ER stress in detail. Several studies addressing ER stress and the UPR employ the reducing agent DTT that is known to induce the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER of plants (21–23). To investigate SDF2 expression upon UPR induction, total RNA was isolated from 6-day-old wild-type (WT) seedlings after incubation with DTT. Semi-quantitative as well as quantitative RT-PCR revealed a ∼3-fold increase of SDF2 expression in response to DTT (Fig. 1, A and B). The expression of SDF2 is similar to those of known molecular Arabidopsis UPR markers such as the ER chaperone of glycoproteins, calreticulin (CRT2) and the ER chaperones of the HSP 70 family BIP1–3 (Fig. 1A). To substantiate SDF2 induction, polyclonal antibodies were generated that specifically recognize the Arabidopsis SDF2 protein (predicted molecular mass, 24 kDa) (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S4D). Immunoblot analyses of microsomal membrane fractions from DTT-treated WT seedlings demonstrated that not only the SDF2 transcript but also the amount of the SDF2 protein highly increases in response to ER stress (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

SDF2 expression in Arabidopsis seedlings in response to ER stress. A, transcript levels of SDF2, CRT2 (At1g09210), BIP1/2 (At5g28540; At5g42020), BIP3 (At1g09080), and the control gene PP2A (At1g13320) were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR as indicated. WT and sdf2-2 mutant seedlings were treated with 10 mm DTT for 5 h or mock treated. B, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of SDF2 transcripts in WT seedlings treated with 10 mm DTT for 5 h (+DTT) or mock treated. Analyzed cDNA preparations are identical to those used in A. Transcript levels were normalized to PP2A. Expression levels in untreated WT seedlings were arbitrarily defined as 1. C, elevation of the SDF2 protein levels upon treatment with increasing concentrations of DTT. Microsomal fractions prepared from seedlings grown in the presence (2 mm and 2.5 mm) or absence of DTT were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot using SDF2 antibodies. SDF2 shows an apparent molecular mass of 21 kDa. An asterisk marks a cross-reactive band. Loading of equal protein amounts was confirmed by the detection of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase subunit c (VHA-c). D–F, SDF2 promoter activity. Transgenic plants harboring the ProSDF2:GUS fusion were stained for GUS activity (1 h at 37 °C) to monitor sites of SDF2 expression. Staining patterns were recorded using a Leica MZ FLIII stereo microscope. D, seedlings at 7 days after germination either grown on plates with MS medium (−) or medium supplemented with 2 mm DTT (+). Bar: 1 mm. E, seedlings 7 days after germination grown overnight in MS medium previous to the addition of 1 mm DTT (+). Mock-treated seedlings grown in MS medium served as control (−). F, seedlings 5 days after germination were incubated in MS medium (−) or MS medium supplemented with 5 μg/ml tunicamycin (+) for 3 days. Bar: 2 mm.

Because UPR target gene transcripts accumulate in response to ER stress, we examined the promoter activity of SDF2 during DTT treatment at cell- and tissue-specific levels. To this end, we established transgenic reporter plants expressing the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene under the control of the SDF2 promoter (ProSDF2:GUS). Under normal growth conditions in the early developing seedling ProSDF2:GUS expression was mainly observed in the cotyledons and in meristematic and elongation zones of roots (supplemental Fig. S1A). At later developmental stages ProSDF2:GUS expression was detected in several tissues including vascular bundles and hydathodes of the cotyledons and in meristematic and elongation zones of shoots and primary and lateral roots (supplemental Fig. S1). Under DTT-induced ER stress conditions, SDF2 promoter activity was dramatically increased especially in meristematic and elongation zones of primary and lateral roots (Fig. 1, D and E and supplemental Fig. S2). We observed very similar ProSDF2:GUS expression when tunicamycin, an inhibitor of protein N-glycosylation that results in the inability of proteins to be N-glycosylated and folded correctly, was used to induce the UPR (Fig. 1F and supplemental Fig. S3). In summary, our data show that SDF2 expression is highly responsive to ER stress conditions that interfere with protein folding.

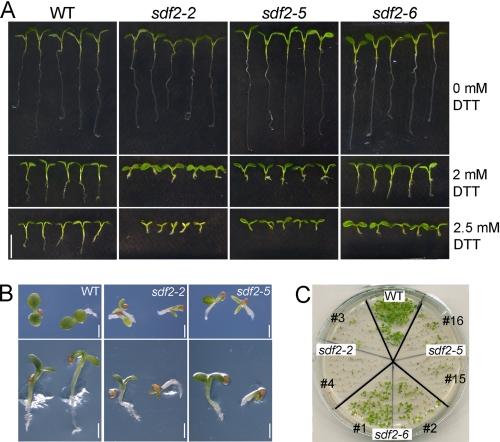

SDF2 Is Required for Seedling Development under ER Stress Conditions

To further access the function of SDF2 in vivo, we analyzed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants sdf2-2 (SALK_141321; insertion at position bp +294, exon 2), sdf2-5 (WiscDSLox293–293invl23; insertion at position bp +1080, exon 5) and sdf2-6 (SALK_077481; insertion at position bp −294, promoter region) obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B). The individual sdf2 mutants were analyzed for SDF2 transcripts by RT-PCR and for the SDF2 protein by immunoblot analysis. Whereas the sdf2-6 mutant line carrying a promoter insertion still displayed reduced levels of SDF2 transcript, no SDF2 transcript was detectable in mutants sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 (supplemental Fig. S4C). Accordingly, detectable but dramatically reduced SDF2 protein levels were found in sdf2-6 mutant seedlings; however, no SDF2 protein was present in extracts of the knock-out mutants, sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 (supplemental Fig. S4D). For all three mutant lines no visible phenotype was observed under normal growth conditions (data not shown). Because our analyses demonstrated SDF2 induction upon perturbation of ER homeostasis, we particularly examined possible DTT and tunicamycin sensitivity of sdf2 mutants. To this end, Arabidopsis WT and mutant seeds were sown on DTT-containing medium. Detailed characterization of the morphological phenotype at day 6 after germination revealed that growth of WT seedlings was retarded in the presence of DTT. Strong inhibition of primary root elongation and formation of root hairs and lateral roots was observed (Fig. 2, A and B). Compared with WT, sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 seedlings showed pronounced growth retardation and in the majority of cases cotyledons failed to expand (Fig. 2, A and B, supplemental Table S2). Hypocotyls and primary roots were extremely short and formation of root hairs and lateral roots was suppressed. The promoter-insertion line sdf2-6 showed a similar but less pronounced phenotype (Fig. 2, A and B, supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, in contrast to both knock-out mutants the majority of sdf2-6 seedlings could overcome growth retardation after a period of up to 18 days but remained pale green compared with WT seedlings (Fig. 2C). In addition, sdf2 mutants showed increased sensitivity toward tunicamycin again sdf2-6 was less affected (supplemental Fig. S5). In contrast, sensitivities toward stress conditions that are not related to ER stress such as salt and osmotic stress were comparable between all three sdf2 mutants and WT seedlings (supplemental Table S2). Taken together, phenotypic characterization of independent mutant alleles revealed that sdf2 mutants are sensitive toward ER stress induced by the accumulation of unfolded proteins. In the absence of sdf2, seeds germinate but seedlings are not able to develop further in the presence of prolonged ER stress conditions. Yet, minor amounts of SDF2 protein allow seedlings to gradually overcome ER stress.

FIGURE 2.

Growth phenotypes of sdf2 mutant seedlings upon DTT treatment. A, root morphology of sdf2 mutants compared with WT. Seedlings were grown on MS medium in the presence or absence of DTT as indicated. After 7 days of growth, seedlings were placed on MS plates for documentation. Bar: 5 mm. B, phenotype of sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 seedlings grown on MS supplemented with 2.5 mm DTT compared with WT. The appearance of eight-day-old seedlings grown horizontally (upper panel) or vertically (lower panel) was documented with higher magnification. Bars: 1 mm. C, developmental phenotype of sdf2 mutants after 18 days of DTT treatment compared with WT. For each mutant line seeds from different individuals were analyzed.

UPR Is Activated under DTT-induced ER Stress in sdf2-2 Mutants

Phenotypic characterization of Arabidopsis sdf2 mutants suggested that SDF2 is a crucial protein for the UPR and its loss-of-function may cause impairment of this process. To exclude the possibility that the absence of SDF2 indirectly interferes with the onset of UPR, we analyzed the expression of known molecular UPR markers in the knock-out mutant sdf2-2 in response to DTT treatment. Thereto, total RNA was isolated from 6 day-old seedlings after incubation with DTT and transcripts of CRT2, BIP1/2, and BIP3 were monitored by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, upon DTT treatment the representative UPR marker transcripts accumulated in sdf2-2 mutants to the same extend as in WT Arabidopsis. These results suggest that deletion of SDF2 does not interfere with sensing of ER stress and that normal induction of UPR target genes occurs in the absence of the SDF2 protein. In combination with the fact that SDF2 is significantly induced in the course of the UPR and, that sdf2 seedlings are ER stress hypersensitive our data demonstrate that SDF2 represents a functional target of the UPR in Arabidopsis.

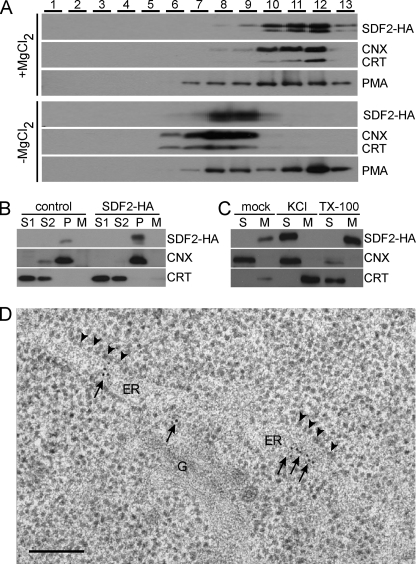

SDF2 Is Associated with the Rough ER Membrane

To characterize the SDF2 protein in more detail, we transiently expressed a HA epitope-tagged version in N. benthamiana leaves. Microsomal preparations were fractionated by isopycnic centrifugation on a continuous sucrose density gradient. On sucrose gradients, Mg2+ ions stabilize the rough ER and ER bands are located in the fractions with the highest sucrose density. In the absence of Mg2+ ions, ribosomes dissociate from the ER, shifting ER bands to fractions with lower densities, whereas bands of other compartments are not affected (24). Immunoblot analyses of gradient fractions showed that SDF2-HA co-localizes with the protein marker constituents of the rough ER calnexin (CNX) and calreticulin (CRT), and specifically follows those upon depletion of Mg2+ ions (Fig. 3A). Further, soluble and membrane fractions were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. As shown in Fig. 3B, the luminal ER protein CRT is exclusively present in the soluble fractions (lower panel). In contrast, SDF2-HA (upper panel) and the ER membrane protein CNX (middle panel) are predominantly found in the membrane fraction. Treatment with 0.5 m KCl resulted in the release of SDF2, but not CNX, from the ER membrane (Fig. 3C). Under low salt conditions, detergent treatment of membranes resulted in the precipitation of SDF2 probably due to the formation of protein aggregates (Fig. 3C). In addition, localization of SDF2 by immunogold electron microscopy (EM) revealed that ER cisternae are intensely labeled in DTT-induced WT seedlings (Fig. 3D and supplemental Fig. S6). In contrast, virtually no labeling is obtained in non-induced WT seedlings and DTT-induced sdf2-2 mutants (supplemental Fig. S6). In summary, our data prove that SDF2 resides in the rough ER, though in contrast to mammalian SDF2L1 (7), Arabidopsis SDF2 does not contain a typical HDEL ER-retention signal (supplemental Fig. S7A).

FIGURE 3.

Subcellular localization of SDF2. A, sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Microsomal membranes derived from tobacco leaves transiently expressing SDF2-HA were fractionated in the presence (+MgCl2) or absence (−MgCl2) of Mg2+ ions. Gradient fractions from top (1) to bottom (13) were analyzed by immunoblot using specific antibodies directed against SDF2-HA, CNX, and CRT (ER marker), and plasma membrane H+-ATPase (PMA) (PM marker). SDF2 co-fractionates in both gradients with the ER marker proteins. B, cell fractionation. Tobacco protoplasts transiently expressing SDF2-HA were fractionated in supernatant (S1) containing cytosol, supernatant (S2) containing microsomal contents and membrane pellet fraction (P) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Protoplast culture medium (M) was concentrated. SDF2-HA was detected by immunoblot with anti-HA antibodies. Endogenous CNX and CRT were detected using specific antibodies. Protoplasts transformed with the empty vector served as control. C, membrane association of SDF2. Arabidopsis microsomal membranes were treated with extraction buffer supplemented with 0.5 m KCl or 1% Triton X-100 (TX-100) as indicated. Supernatant (S) and microsomal membranes (M) were separated by ultracentrifugation. SDF2, CNX, and CRT were detected using specific antibodies as indicated. D, immunogold labeling of cryosections with SDF2 antibodies. Six-day-old high pressure frozen Arabidopsis root tips labeled with antibodies against SDF2 and goat anti rabbit gold (10 nm) secondary antibodies. Golgi stacks (G) and cisternae of the ER (ER) are easily identifiable. Membranes of the ER are low in contrast therefore bound ribosomes have been indicated by arrowheads. Bar represents 200 nm. In WT plants treated with 2 mm DTT the ER is intensely labeled (arrows). Corresponding control experiments are shown in supplemental Fig. S6.

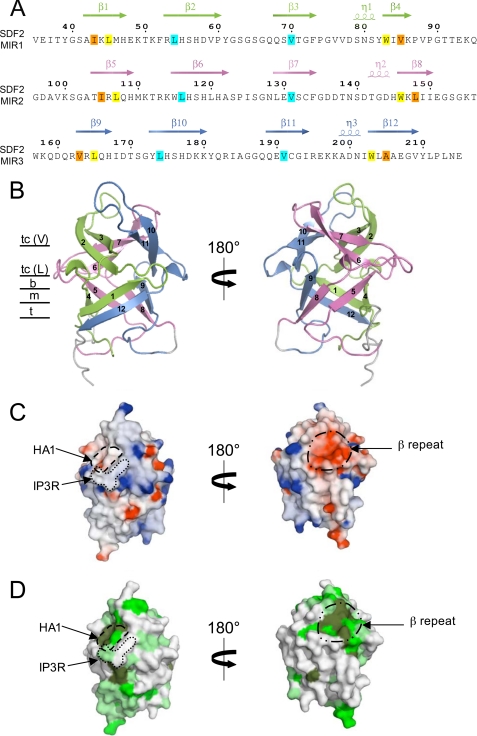

The Three-dimensional Structure of SDF2 Adopts a β-Trefoil Fold

The SDF2 protein contains three MIR motifs consisting of residues 34–88 (MIR1), 96–151 (MIR2), and 154–208 (MIR3) (supplemental Fig. S7A). The MIR motif is named after three of the proteins in which it occurs: protein O-mannosyltransferase (Pmt), inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), and ryanodine receptor (RyR) (25). MIR motifs are often found in multiple copies, which are characteristically arranged in triplet. However, the function of this domain is not clear to date. To learn more about SDF2 and its MIR motifs, we determined its three-dimensional structure. A construct encoding amino acid residues 24–218 of SDF2 was expressed, and the corresponding protein was purified (16). The crystal structure was determined by molecular replacement at 1.95 Å resolution (Table 1). The SDF2 structure (residues 35–215) shows the typical β-trefoil fold and consists of 12 β-strands and three 310 helices forming a globular barrel with approximate dimensions 50 × 35 × 30 Å3. The β-strands are arranged into six two-stranded hairpins, three of which form a barrel while the other three form a triangular array capping the top of the barrel (Fig. 4, A and B). The β-trefoil fold is made up of three structural repeats which correspond to the three MIR motifs, giving rise to a pseudo 3-fold symmetry. As expected from the internal sequence similarities the structures of the different repeats are very similar apart from the variable-sized loops connecting the strands. The β-trefoil fold is found in a number of proteins which generally share little or no detectable sequence similarity. Only key hydrophobic residues, essential for maintaining the β-trefoil fold, are invariant among the family members (26). When the sequence conservation of SDF2-type proteins is analyzed, the triangular cap and residues located at the bottom and the middle layers of the β-trefoil core structure give high scores while rather low conservation is observed in the top layer (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, leucine and valine residues of the second and third strand of each MIR motif are highly conserved (Fig. 4A). In SDF2, Leu-54, Leu-116, and Leu-174 form a hydrophobic layer just at the top of the bottom layer of the barrel (supplemental Fig. S7B). Replacement of these leucines by alanines results in unfolding and aggregation of the SDF2 mutant proteins during purification (data not shown), further emphasizing their crucial role in maintaining the β-trefoil structure.

FIGURE 4.

Structure of SDF2. A, protein sequence of SDF2. Location of the 12 β-strands and three 310 helices is depicted. The α-repeat (MIR1 motif) is colored in green, the β-repeat (MIR2 motif) in magenta, and the γ-repeat (MIR3 motif) in blue. Conserved residues at the interior of the β-trefoil barrel arranged in the bottom and middle layers are highlighted in yellow and orange, respectively. Key residues of the triangular cap are highlighted in cyan. B, ribbon representation of the SDF2 structure. The colors are the same as in A. The view on the right is rotated by 180° along a vertical axis with respect to the view on the left. β-strands are labeled. The position of the bottom (b), middle (m), and top layer (t) of the β-trefoil barrel is indicated as well as the conserved valines (tc (V)) and leucines (tc (L)) of the triangular cap. The bottom layer is comprised of residues just underneath the triangular cap, with the middle and top layers lying parallel to it and away from the cap. Figures were generated with PyMOL. C, same view as in B. The molecular surface is colored blue and red according to positive and negative electrostatic potential, respectively. Potential surfaces were calculated with GRASP (46). The corresponding IP3 binding site in IP3R and sugar binding site in HA1 are shown on the left panel. The conserved and highly negatively charged region at the MIR2 motif (β-repeat) is contoured on the right panel. D, same view as in B. The degree of sequence conservation within the SDF2 family is mapped onto the surface of SDF2. Dark green and light green indicate residues that are highly or partially conserved, respectively. Conservation scores were determined with the program Consurf (consurf.tau.ac.il) on the basis of 26 sequences. The corresponding IP3 binding site in IP3R, the sugar binding site in HA1 and the conserved and highly negatively charged region at the MIR2 motif are shown as in C.

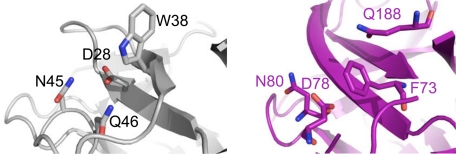

Functional regions were proposed to reside within the loop regions of the β-trefoil family, which are usually not conserved (27). Altogether the loop regions of SDF2 account for about 70% of the molecular surface. The loops separating the last two β-strands (β3-β4, β7-β8, β11-β12) contain a 310 α helix while the other loops do not adopt a particular structure (Fig. 4A). To probe the presence of potential binding sites within the structure, we analyzed SDF2 structural homologs. Analysis using the Dali server (28) indicated that SDF2 presents the highest homology with the hemagglutinin component (HA1) of the progenitor toxin from Clostridium botulinum (29) (apart from IP3R and the unknown function protein used for the molecular replacement) (supplemental Fig. S8). HA1 consists of two β-trefoil domains and was shown to interact with carbohydrates containing galactose moieties (29). SDF2 superimposed well with the first β-trefoil (r.m.s.d. 2.1 Å, supplemental Fig. S8A) and especially at the level of the carbohydrate binding site identified for HA1 and made of 4 conserved residues (Asp, Asn, Gln, and one aromatic residue) at the α repeat in the triangular cap (Fig. 5). Interestingly, this region corresponds in SDF2 to a conserved and negatively charged patch located at the MIR1 repeat (HA1 region on Fig. 4, C and D). These findings strongly suggest that this region might accommodate a yet unidentified carbohydrate ligand. Further analysis of surface characteristics revealed that SDF2 exhibits another highly conserved and negatively charged region, at the MIR2 repeat in the triangular cap (named β repeat on Fig. 4, C and D), that might as well act as an interaction surface with ligand or protein partner.

FIGURE 5.

Close-up of the putative carbohydrate binding site in SDF2. Same view as in Fig. 4B left and supplemental Fig. S8A. Residues involved in carbohydrate binding in HA1 are shown in gray/black on the left panel. Corresponding SDF2 residues are shown in magenta on the right panel. Asn-45 located prior to β-strand 4 and Trp-38 from β-strand 3 of HA1 superimpose with Asn-80 and Phe-73 of SDF2 while Asp-78 and Gln-188 of SDF2 might play the role of Asp-28 and Gln-46 of HA1 to form hydrogen bonds with a sugar moiety.

DISCUSSION

In Arabidopsis seedlings, SDF2 transcription is activated upon UPR induction by DTT and tunicamycin treatment and consistently, SDF2 protein levels increase (Figs. 1 and 3). Comprehensive transcriptome analyses also identified the SDF2 gene to be up-regulated in response to various UPR-inducing reagents such as DTT (21), tunicamycin, and l-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid, a proline analog that prevents folding of polypeptides (23); and during heat stress (30) that inter alia induces protein aggregation. Likewise, time course of SDF2 transcript induction resembles BIP1, BIP2, CRT, CNX, and PDI transcripts (Ref. 23, Fig. 1A and data not shown). Accordingly, we identified various cis-acting ER and heat stress response elements in the SDF2 promoter region (data not shown; Refs. 22, 31). Further, SDF2 is highly expressed in fast growing, and/or differentiating cells and meristematic regions (Fig. 1, D–F, supplemental Fig. S1). The enhanced promoter activity of SDF2 in root tips (Fig. 1, D–F, supplemental Fig. S1) correlates with reported expression pattern of the ER-chaperones BIP2 (32) and CRT1a (33) and the UPR sensors IRE1-1/2 (34). Taken together, expression profiles, promoter elements, and the very similar transcriptional induction pattern of Arabidopsis SDF2, BIP1–3, CRT, CNX, and PDI upon treatment with various agents that are known to induce protein unfolding but feature different modes of action qualify SDF2 as a general component of the UPR in plants.

Deletion Mutants Validate SDF2 as a Functional Target of the UPR in Vivo

Arabidopsis sdf2 seedlings display a strong developmental and morphological phenotype, specifically under ER stress. However, the transcriptional activation of known UPR target genes is not altered in the sdf2-2 mutant (Fig. 1A). Thus, the accumulation of unfolded proteins is still perceived and sensing of ER stress still occurs. Compared with WT seedlings, sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 mutants show pronounced growth retardation and impaired root growth upon DTT treatment (Fig. 2). WT seedlings are able to overcome the induced ER stress with time, form green expanded cotyledons and develop further (Fig. 2C). Similar effects have been described previously for WT seedlings after tunicamycin treatment (35). Thus, delayed growth and changes in root morphology in the early phase of seedling development is, at least partially, a consequence of the cellular response to ER stress conditions. A complete lack of SDF2 in sdf2-2 and sdf2-5 mutants resulted in growth arrest in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of DTT, inability to form open green cotyledons and death of the majority of seedlings (Fig. 2, supplemental Table S2). The severity of the observed phenotype is highly dose-dependent. The sdf2-6 knock-down mutant displayed a conditional phenotype where symptoms were clearly visible in the early phase of seedling growth but less apparent when growth continued (Fig. 2). Taken together, the characterization of the different Arabidopsis sdf2 mutants demonstrates that SDF2 is a vital protein during acute ER stress.

In plants, responses similar to the UPR have been observed upon environmental stimuli and developmental programs that require enhanced protein biosynthesis and secretion (2). For example, in the course of pathogen response, the secretory machinery is prepared for secretion of defense proteins through the up-regulation of genes encoding ER-resident chaperones and protein-folding helpers. Interestingly, upon pathogen infestation not only transcription of BiP, CNX, CRT, and PDI, but also SDF2 is enhanced (36). Very recently, in a screen for mutants that affect the function of the surface-exposed leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase EFR, sdf2 mutants were identified that are more susceptible to bacterial and fungal pathogens (10). In line with our findings, an important role of SDF2 for the maturation of pattern-recognition receptors and other secreted components of plant response in the ER was suggested.

SDF2 May Act as Mediator for the Interaction of Different Partners

Molinari and Helenius (37) proposed a conserved mechanism where during translocation of a glycoprotein into the ER, a choice is made between chaperone systems. The closer the N-glycans are to the N terminus of the nascent protein, the higher the tendency to interact with CNX or CRT, two ER chaperones with lectin activity (38). CNX and CRT prevent aggregation of misfolded proteins in the ER, and promote folding via interactions with the thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 that catalyzes disulfide formation. If the first attempts to fold fail, the protein can shift to an alternative pathway that is based on the abundant ER chaperones BiP, a chaperone of the Hsp70 family and GRP94, the ER paralog of the Hsp90 family (1). In mammals, BiP/GRP94 are the abundant components of a multiprotein complex including the calcium-binding protein 1 (CaBP1), protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI), ER Hsp40-like co-chaperone ERdj3, cyclophilin B, the thiol reductase ERp72, the major nucleotide exchange factor for BiP GRP170, UDP-glucosyltransferase, and SDF2L1 (6). Direct interactions between murine SDF2L1 and ERdj3 have been demonstrated (9). Conservation of this folding promoting complex between animals and plants is suggested. Arabidopsis SDF2 has been identified as an interaction partner of ERdj3B in Y2H assays (Ref. 10),7 and both proteins co-immunoprecipitate with BiP even under non ER stress conditions (10). Further, expression of SDF2 and ERdj3B (39), SHEPHERD the ER-resident GRP94 homolog, different PDI isoforms, HSP90, UDP-galactose transporters, and the cyclophilin ROC7 are tightly coordinated (31). In contrast to the CNX/CRT pathway, components with carbohydrate binding potential have not been identified in the BiP/GRP94 pathway so far. SDF2-type proteins might represent such elements.

The three-dimensional structure of Arabidopsis SDF2 revealed a β-trefoil fold that is made up of three structural repeats which correspond to the three MIR motifs giving rise to a pseudo 3-fold symmetry (Fig. 4). The β-trefoil fold was originally described for the structure of Kunitz soybean trypsin inhibitor (40) and is found in several other proteins including lectins such as the Ricinus communis ricin B-chain (41), Amaranthus caudatus agglutinin (42), and the ligand binding domains of mammalian IP3R (43, 44). In many instances the β-trefoil domain acts as an oligosaccharide binding unit. However, position, orientation and interactions between β-trefoil domains and carbohydrates vary among different proteins. On a structural point of view SDF2 presents the highest homology with the 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) binding core and suppressor domain of IP3R (43, 44) and with HA1 of C. botulinum progenitor toxin (29). SDF2 superimposes on the first with the first β-trefoil of HA1, especially at the level of the galactose binding site. Although the superimposition of the IP3Rcore domain and SDF2 shows a high conservation of the overall fold, the IP3 binding site is not conserved in SDF2 (supplemental Fig. S8B). These structural comparisons suggest that SDF2 binds a carbohydrate ligand, most likely not IP3. In addition, the surface analyses of the SDF2 structure revealed another highly conserved, negatively charged region named the β-repeat. This region is part of the MIR2 domain and represents another potential region for interactions (Fig. 4D). SDF2 might utilize the β-trefoil fold as a binding platform for multiple interactions. Thereby, SDF2 may act as adaptor for the interaction with different partner or ligands. The 3-fold symmetry is indeed amenable to the presence of functional binding sites in each of the three subdomains, as exploited by the CBM13 modules of Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces olivaceoviridis xylanases (45). Several lines of evidence support our findings. Interaction of SDF2 with glycoproteins is suggested by the recent findings of Nekrasov et al. (10) that identified SDF2 and ERdj3B as being required for function of the membrane glycoprotein EFR. Loss of SDF2 resulted in ER retention and degradation of EFR. The requirement of SDF2 for EFR was linked to N-glycosylation supporting a direct role of SDF2 in ER quality control of glycoproteins. Interaction between SDF2 and membrane glycoproteins such as EFR in the ER could explain why SDF2, per se a soluble protein displayed salt-sensitive membrane association (Fig. 3C). After treatment of membranes with the detergent Triton X-100 SDF2 (Fig. 3C) as well as ERdj3B (39) were recovered in an insoluble fraction that contains protein aggregates and might derive from multiprotein complexes. A challenging task will be to unravel the precise molecular function of the SDF2-type proteins in ER protein quality control and the UPR. The established Arabidopsis system will provide an excellent tool to address this question in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Hinz and P. Pimpl for technical advice. We are very grateful to R. Serrano and group members for the generous help in analyzing stress-induced growth phenotypes. We are grateful to M. Boutry, P. Pimpl, and K. Schumacher for providing antibodies. We thank M. Buettner for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft (SFB638).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3MAL) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S8.

A. Schott and S. Strahl, unpublished data.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GUS

- β-glucuronidase

- MIR motif

- motif conserved between protein O-mannosyltransferase, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, and ryanodine receptor

- MS

- Murashige and Skoog salts

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- WT

- wild-type

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- SDF

- stromal cell-derived factor

- CNX

- calnexin

- CRT

- calreticulin

- r.m.s.

- root mean square.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anelli T., Sitia R. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 315–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitale A., Boston R. S. (2008) Traffic 9, 1581–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ron D., Walter P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urade R. (2007) FEBS. J. 274, 1152–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caramelo J. J., Parodi A. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10221–10225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meunier L., Usherwood Y. K., Chung K. T., Hendershot L. M. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4456–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuda S., Sumii M., Masuda Y., Takahashi M., Koike N., Teishima J., Yasumoto H., Itamoto T., Asahara T., Dohi K., Kamiya K. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280, 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamada T., Tashiro K., Tada H., Inazawa J., Shirozu M., Shibahara K., Nakamura T., Martina N., Nakano T., Honjo T. (1996) Gene 176, 211–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bies C., Blum R., Dudek J., Nastainczyk W., Oberhauser S., Jung M., Zimmermann R. (2004) Biol. Chem. 385, 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nekrasov V., Li J., Batoux M., Roux M., Chu Z. H., Lacombe S., Rougon A., Bittel P., Kiss-Papp M., Chinchilla D., van Esse H. P., Jorda L., Schwessinger B., Nicaise V., Thomma B. P., Molina A., Jones J. D., Zipfel C. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 3428–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998) Plant J. 16, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf S., Rausch T., Greiner S. (2009) Plant J. 58, 361–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliviusson P., Heinzerling O., Hillmer S., Hinz G., Tse Y. C., Jiang L., Robinson D. G. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 1239–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bubeck J., Scheuring D., Hummel E., Langhans M., Viotti C., Foresti O., Denecke J., Banfield D. K., Robinson D. G. (2008) Traffic 9, 1629–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.daSilva L. L., Taylor J. P., Hadlington J. L., Hanton S. L., Snowden C. J., Fox S. J., Foresti O., Brandizzi F., Denecke J. (2005) Plant Cell 17, 132–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radzimanowski J., Ravaud S., Schott A., Strahl S., Sinning I. (2010) Acta Crystallogr Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66, 12–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weigel D., Glazebrook J. (2002) Arabidopsis: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 18.CCP4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez I. M., Chrispeels M. J. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 561–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwata Y., Fedoroff N. V., Koizumi N. (2008) Plant Cell 20, 3107–3121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamauchi S., Nakatani H., Nakano C., Urade R. (2005) FEBS. J. 272, 3461–3476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pryme I. F. (1986) Mol Cell Biochem. 71, 3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponting C. P. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 48–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murzin A. G., Lesk A. M., Chothia C. (1992) J. Mol. Biol. 223, 531–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gosavi S., Whitford P. C., Jennings P. A., Onuchic J. N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10384–10389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holm L., Sander C. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 266, 653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue K., Sobhany M., Transue T. R., Oguma K., Pedersen L. C., Negishi M. (2003) Microbiology 149, 3361–3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakuma Y., Maruyama K., Qin F., Osakabe Y., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18822–18827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obayashi T., Hayashi S., Saeki M., Ohta H., Kinoshita K. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D987–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koiwa H., Li F., McCully M. G., Mendoza I., Koizumi N., Manabe Y., Nakagawa Y., Zhu J., Rus A., Pardo J. M., Bressan R. A., Hasegawa P. M. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 2273–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen A., Svensson K., Persson S., Jung J., Michalak M., Widell S., Sommarin M. (2008) Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 912–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koizumi N., Martinez I. M., Kimata Y., Kohno K., Sano H., Chrispeels M. J. (2001) Plant Physiol. 127, 949–962 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe N., Lam E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3200–3210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D., Weaver N. D., Kesarwani M., Dong X. (2005) Science 308, 1036–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molinari M., Helenius A. (2000) Science 288, 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams D. B. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 615–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto M., Maruyama D., Endo T., Nishikawa S. (2008) Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 1547–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLachlan A. D. (1979) J. Mol. Biol. 133, 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutenber E., Robertus J. D. (1991) Proteins 10, 260–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Transue T. R., Smith A. K., Mo H., Goldstein I. J., Saper M. A. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 779–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosanac I., Alattia J. R., Mal T. K., Chan J., Talarico S., Tong F. K., Tong K. I., Yoshikawa F., Furuichi T., Iwai M., Michikawa T., Mikoshiba K., Ikura M. (2002) Nature 420, 696–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosanac I., Yamazaki H., Matsu-Ura T., Michikawa T., Mikoshiba K., Ikura M. (2005) Mol. Cell 17, 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boraston A. B., Bolam D. N., Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J. (2004) Biochem. J. 382, 769–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholls A., Sharp K. A., Honig B. (1991) Proteins 11, 281–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.