History

A 55-year-old female presents with a chief complaint of pain and swelling of the anterior mandible which has continued for approximately 18 months, but which is now resulting in numbness of this area. Appropriate imaging studies were performed.

Radiographic Features

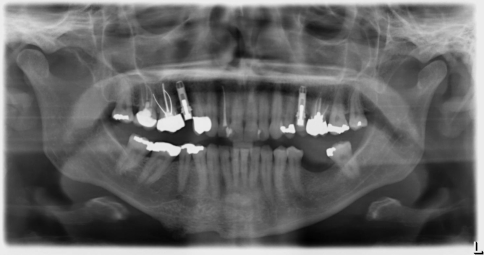

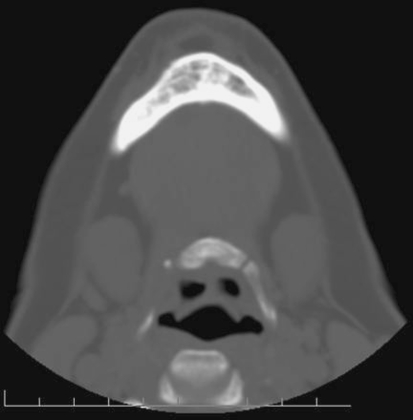

A panoramic radiographic image (Fig. 1) demonstrated a honeycomb pattern of bone in the anterior-inferior mandible that extends from tooth #23 to the area of tooth #29. This prominent bone density and trabeculation could be interpreted as a fibro-osseous lesion. The periphery appears smoothly demarcated from the adjacent unaffected bone but failed to reveal the expansile aspect of the lesion. The panoramic radiograph did show that the inferior border had a scalloped periphery with a concave, semi-lunar appearance at the mental process with involvement of the cortex in this area. This involvement appeared to extend into soft tissue as a separate fragment of speckled bone was noted to be disjointed from the mandible as a clear demarcation is evident. Imaging studies (Fig. 2) showed marked expansion of the anterior mandible anteriorly with internal septations noted. The lesion approached the periapical region of the teeth of the anterior mandible, but was not intimately involved with the teeth.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic radiograph showing a honeycomb pattern of bone

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography image depicting intraosseous loculations and a trabeculated bone pattern

Diagnosis

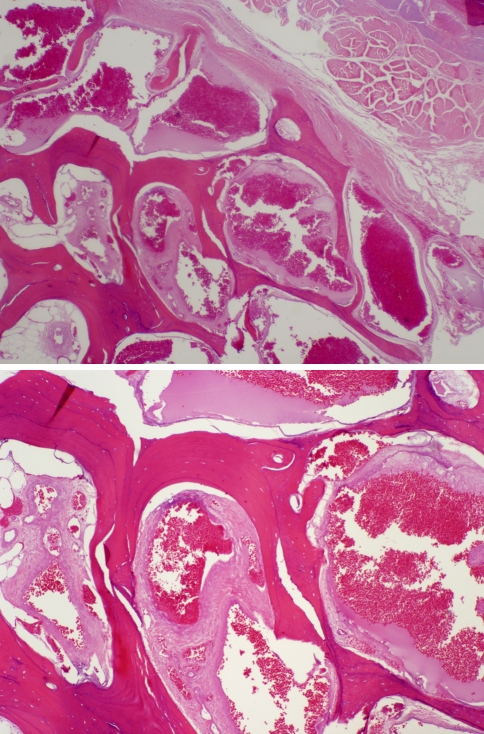

Histologic examination of the decalcified specimen with a hematoxylin and eosin stain (Fig. 3) demonstrated large marrow spaces surrounded by compact trabeculae of thick and thin bone. The bone trabeculae separate numerous large, ovoid, as well as tortuous vascular spaces lined by thin, but plump endothelium supported by varying thicknesses of fibrous connective tissue. Multiple large spaces additionally demonstrated numerous small caliber vessels contained within the large cavity. The luminal area contains an abundance of red blood cells and serum debris. Portions of the vascular proliferation extended to the bone margin and abut soft tissue which consisted of dense fibrous connective tissue and skeletal muscle.

Fig. 3.

Large and small convoluted vascular channels engorged with red blood cells are separated by a network of dense bone which extends into adjacent soft tissue

Discussion

Hemangiomas in an intraosseous location, especially of the jaws, are rarely reported entities. When found, the majority present during the second decade of life and are found to occur in the mandible with a female to male ratio of 2:1 [1]. These lesions have been considered by the World Health Organization as true benign vasoformative neoplasms, or a developmental condition of endothelial origin [2] whereas, other authors believe them to be a hamartoma stemming from the proliferation of mesodermal cells that undergo endothelial differentiation, become canalized, then vascularized [3].

Histologically, hemangiomas consist of a mass of endothelial cells forming vascular spaces of varying size, interspersed with fibrous connective tissue stroma. Bony trabeculae may often be found admixed in the tissue mass [7]. The lesion is classified according to the size of the vascular spaces formed by the proliferating cells with the capillary type consisting of small vessels with pronounced cellularity and stroma, while the cavernous type is composed of larger vessels and sinuses lined by thin endothelium and sparse stroma. A mixed variant exists which possesses features of both the capillary and cavernous types. A fourth variant, the scirrhous type, is characterized by an abundance of proliferating connective tissue [5].

Regardless of histologic type, several clinical features are associated with a central hemangioma of the mandible. Patients often experience a firm, painless swelling of the bone which may or may not cause facial asymmetry [5, 6]. Other reported symptoms are pressure or discomfort, oozing or pulsatile bleeding from the gingiva of teeth in the region of the lesion, a bluish discoloration of the gingiva, mobile teeth, and accelerated exfoliation of teeth [1, 7]. In lesions with high vascular pressure, patients often report a sensation of pulsation, and large lesions extending into adjacent soft tissues may have audible bruits [1]. Despite the benign nature of the lesion, paresthesia in the region is not uncommon. It is crucial to report that patients may not demonstrate any signs or symptoms. Failure to consider and recognize the presence of an intraosseous hemangioma before surgical therapy may lead to significant hemorrhage and even death [9].

Intraosseous hemangiomas possess a varied radiographic appearance and thus cannot be accurately diagnosed on plain films. In general, they can present with an osteolytic pattern possessing a multi-locular “soap bubble” appearance with irregular, poorly defined margins [4, 5, 7]. Many pathologic entities may be described in similar terms and a differential diagnosis would include central giant cell lesion, ameloblastoma, and odontogenic myxoma. As such, angiography can play a crucial role in diagnosis as it can confirm the suspicion of the vascular lesion, delineate its margins, and indicate feeder vessels [4, 7]. Definitive diagnosis of an intraosseous hemangioma cannot be made without histologic examination, but due to the risk of severe hemorrhage, needle aspiration should precede biopsy of any suspicious lesion. The presence of easily aspirated blood with significant volume and brisk hemorrhage from the puncture site should preclude biopsy [5]. In the presence of clinical signs and symptoms, radiographic appearance, positive aspiration, and suggestive arteriograms, biopsy may be deferred and treatment should be initiated with a presumptive diagnosis of intraosseous hemangioma [6].

Several treatment modalities have been recommended and selection is largely dependent on the size of the lesion, the age of the patient, and any anticipated complications [4]. Sclerosing agents such as sodium morrhuate and absolute ethanol may be injected into the lesion, thereby inducing an inflammatory response within the endothelium, resulting in fibrosis and obliteration of the vessels. The inflammatory induced damage is limited to the vessels, thus sparing the bone; however, high-flow lesions may displace the sclerosing agent too quickly to have a curative effect [4–6]. Irradiation is suggested if the lesion is large or surgically inaccessible. While it may cause regression in some lesions, it is not curative, and recurrences have been reported [4, 6]. Radiation also possesses high-risk side effects such as damage to growth centers in developing patients as well as possible induction of neoplastic transformation [4, 7]. Cryotherapy has been reported to have some measure of success in small lesions, but tends to have undesirable effects on adjacent tissues, including loss of innervation [1, 7]. Embolization of large vessels feeding the lesion is often recommended. Embolizing agents such as silicone pellets or isobutyl cyanoacrylate are injected into large vessels under fluoroscopic control. This technique carries potentially severe complications such as embolization of pulmonary or cerebral vessels [9]. Embolization has been shown to be temporary, with the development of collateral vessels restoring the lesion to pre-procedure size [7]. Therefore, its primary use is adjunctive to surgery to reduce intraoperative bleeding [1, 7].

Surgical intervention is generally accepted as the definitive treatment, with en bloc resection the recommended procedure. Extension beyond the lesion reduces the risk of disruption and may reduce the risk of catastrophic hemorrhage [8]. Ligation of feeder vessels should precede the removal of the lesion. The potential for anatomic variation emphasizes the importance of angiography for proper identification of vessels associated with the primary lesion [4, 8]. Even with proper identification and pre-operative planning, significant bleeding is to be expected intra-operatively, and clinicians should be prepared for rapid transfusion [8]. Upon successful surgical removal of the lesion, appropriate reconstruction measures may be taken to restore the patient to optimum function.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Beziat JL, Marcelino JP, Bascoulergue Y, Vitrey D. Central vascular malformation of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55(4):415–419. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler CP, Wold L, Vascular tumours. In: Fletcher C, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 320.

- 3.Alves S, Junqueira JL, Oliveira EM, Pieri SS, Magalhães MH, Dos Santos Pinto D, Jr, et al. Condylar hemangioma: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(5):e23–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei-Yung Y, Guang-Sheng M, Merrill RG, et al. Central hemangioma of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1154–1160. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marwah N, Agnihotri A, Dutta S. Central hemangioma: an overview and case report. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:460–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayward JR. Central cavernous hemangioma of the mandible: report of four cases. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:526–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadowsky D, Rosenburg RD, Kaufman J, et al. Central hemangioma of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;52(5):471–477. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90356-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamberg MA, Tasanen A, Jääskeläinen J. Fatality from central hemangioma of the mandible. J Oral Surg. 1979;37(8):578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneko R, Tohnai I, Ueda M, et al. Curative treatment of central hemangioma in the mandible by direct puncture and embolisation with n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) Oral Oncol. 2001;37:605–608. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(00)00119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]