Abstract

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a rare extramedullary malignant tumor composed of immature myeloid cells. It is strongly associated with a well known or covert acute myeloid leukaemia, chronic myeloproliferative diseases or myelodysplastic syndromes. Intraoral MS scarcely occurs. An unusual case of acute myeloid leukaemia, which was diagnosed by mandibular MS that was developed in the alveolar socket after a dental extraction, is reported. The histological examination (including immunohistochemical analysis) of a subsequent biopsy showed infiltration of the oral mucosa by neoplastic cells. This lesion was therefore classified as acute myeloid leukaemia. The patient was referred to oncologists that confirmed the initial diagnosis. The patient underwent chemotherapy and the mandibular tumor disappeared. Forty days later, a relapse of the disease, which appeared as a great-ulcerated lesion, was developed in the hard palate. Thirty days after the second chemotherapy had finished, a new intraoral tumor was developed in the vestibular maxillary gingiva. Review of the literature shows no report of intraoral relapse and particularly multiple relapse of a MS that involves the oral cavity. Even though MS is encountered infrequently in the oral cavity, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of conditions (especially tumors) with a similar clinical appearance.

Keywords: Myeloid sarcoma, Granulocytic sarcoma, Chloroma, Acute myeloid leukaemia, Oral tumors

Introduction

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a rare extramedullary malignant tumor composed of immature myeloid precursor cells. The term MS has replaced the term granulocytic sarcoma and chloroma which were used in the past.

This tumor is strongly associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes [1–3]. MS is developed in 1–8% of patients with AML [2, 4] and it has been reported to be more common in myelomonoblastic and myeloblastic subtype [1, 5]. However, some authors support that intraoral MS more often occurs in patients with the subtype of granulocytic origin [6, 7].

MS may develop in a variety of areas, including the skin, bones, gastrointestinal tract, and upper respiratory tract [2, 6, 7]. It has been reported that in 16% of cases the tumor was found in the head and neck, although intraoral MS rarely occurs [2].

The aim of this article is to describe an unusual case of AML, which was further investigated due to diagnosed MS in a mandibular extraction socket. Moreover an intraoral relapse of the neoplasm is reported, which appeared as a maxillary lesion and observed in the same patient twice.

Case Report

A 70-year old female, suffering from fatigue, was referred to us because of a rapidly growing left-sided mandibular tumefaction. Twenty days before, the patient had the left mandibular first premolar extracted.

The intraoral physical examination revealed a painless ulcerated mass, 1.5 × 2 cm in the alveolar socket of the extracted tooth (Fig. 1). The radiographic examination of the mandible did not show any bone damage.

Fig. 1.

Clinical picture of the mandibular myeloid sarcoma in a case of acute myeloid leukaemia

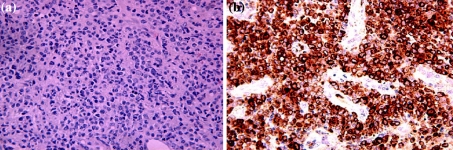

Tissue biopsy demonstrated a monomorphous population of small to medium-size cells resembling atypical lymphocytes which stained positive for CD43 and lysozyme (Fig. 2a, b). Intermingled with these atypical lymphocytes were a few myeloblasts (MPO-positive). This lesion was therefore classified as AML. The patient was referred to oncologists for evaluation and further examination. Complete blood investigation and flow cytometry of peripheral blood confirmed the diagnosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan detected no other areas affected by the disease.

Fig. 2.

a Photomicrograph showing that the tumor consists of a monomorphous population of small to medium cells that resemble atypical lymphocytes (Haematoxylin and Eosin). b Positive immunohistochemical expression of lysozyme cells in the malignant cells

The patient received per os etoposide (2/weekly for 3 weeks) and complete remission of the lesion was noted 3 weeks after treatment.

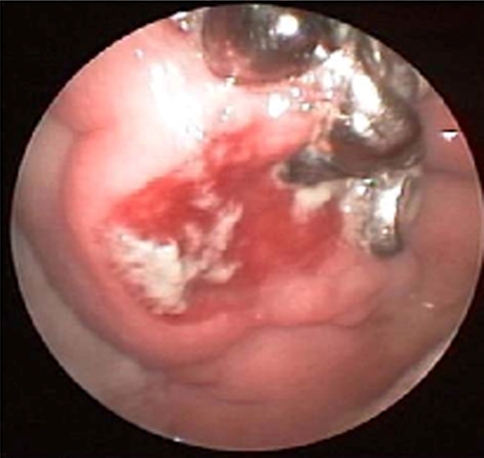

Forty days later the patient returned to the hospital with a new ulcerated lesion on the right hard palate (Fig. 3). Biopsy material from this site was identical to the mandibular lesion and MS was diagnosed. The lesion was considered a relapse of the disease and the patient underwent a new series of chemotherapy with total response on the 3rd week. Thirty days later a tumor was developed on the right vestibular maxillary gingiva. A biopsy was done and the histological examination of the specimen reached the same diagnosis as before. The maxillary tumor was a second intraoral relapse of the disease.

Fig. 3.

The first intraoral relapse of the disease in the hard palate

Five months later the patient passed away.

Discussion

Less than 40 cases of intraoral MS have been published in the English literature. According to our knowledge, there are very few published cases in which MS had developed in a socket after a dental extraction [6, 7]. In addition an intraoral relapse of the neoplasm has never been reported.

Maxillary and mandibular gingivae are the most commonly affected areas. MS typically appears as a localized, solitary painless or moderately painful tumor. A superficial ulceration of the tumor mass is often present. Intraoral MS in the form of multiple tumors or as gingival enlargement has been reported, although it is extremely rare. In particular, only two cases where the MS involved the maxilla and the mandibular gingiva simultaneously have been reported [7, 8] and only one where the MS manifested with gingival enlargement in maxillary and mandibular arches [9]. Review of the literature showed no reports of intraoral relapse and particularly multiple relapse of an MS that involved the oral cavity.

The clinical diagnosis of MS is difficult and the definitive diagnosis can only be made after histological and immunohistochemical analyses.

It is remarkable that in clinical practice misdiagnosis of MS occurs frequently. Intraoral MS can often be misdiagnosed mainly as lymphoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, and less frequently as metastatic tumor and various types of sarcoma including the Ewing sarcoma. Clinically, distinguishing MS from intra-oral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or squamous cell carcinoma is difficult. Histological, MS has sheets of monomorphic polyhedral cells with irregular nuclear contours. Diagnosis is complicated by the diversity and inconsistency of its morphologic features [7]. Immunohistochemical studies may help in reaching a definitive diagnosis because myeloid cells are reactive to antibodies against lysozyme, myeloperoxidase and chloroacetate esterase. Also MS myeloblasts usually express myeloid-associated antigens such as CD43, but are not reactive with lymphoid antigens. In addition flow cytometry and cytogenetics may help in a definitive diagnosis.

Furthermore, it may also be misdiagnosed clinically as inflammatory and reactive hyperplasia such as periodontal abscess, peripheral giant cell granuloma, and pyogenic granuloma, however, pathologic evaluation would rule out these entities [6, 7, 10]. Imaging studies can also be useful. Magnetic resonance intensity (MRI) scans of MS exhibit low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, which helps to rule out inflammatory lesions [11].

The majority of intraoral MS occurs in patients with known AML, but some of them are unaware of their AML disease. An appropriate hematologic analysis is necessary to reach the correct diagnosis. The diagnosis has clinical relevance because it can be the first sign of an AML. Furthermore, the tumor occurs as a forerunner of an AML in non-leukemic individuals in which MS portends an ominous prognosis. According to Rodriguez et al. [12], in most MS patients, AML develops in approximately 10 months.

The prognosis of patients who have developed MS is poor and strictly related to the clinical course of AML [3, 10]. At an older age AML is a significant adverse prognostic factor [2]. Also, patients with multiple MS have a shorter lifetime than those with only one tumor [2]. In addition, gingival infiltration has been reported as a prognostic factor in AML developed in childhood [13].

Treatment of the tumor depends on the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation. There doesn’t exist a uniform treatment for intraoral MS, however, systemic chemotherapy and local radiotherapy remain the main treatment modalities.

Contributor Information

Mattheos K. Papamanthos, Email: manpapaman@hotmail.com

Alexandros E. Kolokotronis, Email: chrisa772002@yahoo.gr

Haralampos E. Skulakis, Email: skulakis@otenet.gr

Angela-Monika A. Fericean, Email: fev@mail.gr

Matina T. Zorba, Email: zormpam@gmail.com

Apostolos T. Matiakis, Email: apismat@yahoo.gr

References

- 1.Amin KS, Ehsan A, McGuff HS, Albright SC. Minimally differential acute myelogenous leukemia (AML-M0) granulocytic sarcoma presenting in the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:516–519. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collela G, Tirelli A, Capone R, Rubini C, Guastafierro S. Myeloid sarcoma occurring in the maxillary gingiva: a case without leukemic manifestations. Int J Hematol. 2005;81:138–141. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.E0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan B, Ethunandan M, Anand R, Hussein K, Ilankovan V. Granulocytic sarcoma of the lips: report of an unusual case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e34–e36. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asna N, Cohen Y, Ben-Yosef R. Primary radiation therapy for solitary chloroma of oral tongue. IMAJ. 2003;5:452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi R, Tawa A, Hanada R, Horibe K, Tsuchida M, Tsukimoto I, Japanese Childhood AML cooperative study Extramedullary infiltration at diagnosis and prognosis in children with acute myelogenous leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:393–398. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomás Carmona I, Cameselle Teijeiro J, Diz Dios P, Fernández Feijoo J, Limeres Posse J. Intra-alveolar granulocytic sarcoma developing after tooth extraction. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:491–494. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(00)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Z, Zhang F, Song E, Ge W, Zhu F, Hu J. Intraoral granulocytic sarcoma presenting as multiple maxillary and mandibular masses: a case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e44–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg E, Peters ES, Krutchkoff DJ. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) of the gingiva: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:1346–1350. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90317-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antmen B, Haytac MC, Sasmaz I, Dogan MC, Ergin M, Tanyeli A. Granulocytic sarcoma of gingival: an unusual case with aleukemic presentation. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1514–1519. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.10.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita K, Abe T, Takeda Y, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the gingival: two case reports. Quintess Int. 2007;38:817–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SS, Kim HK, Choi SC, Lee JI. Granulocytic sarcoma occurring in the maxillary gingiva demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:689–693. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.118287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez JC, Arranz KS, Forcelledo MF. Isolated granulocytic sarcoma: report of a case in the oral cavity. J Oral Maxillof Surg. 1990;48:748–752. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90065-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hisconmez G, Cetin M, Tuncer AM, et al. Children with acute myeloblastic leukemia presenting with extramedullary infiltration: the effects of high-dose steroids treatment. Leuk Res. 2004;28:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]