Abstract

Ectopic cervical thymoma (ECT) is a rare tumor that is frequently misdiagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology and frozen section. Using conventional light microscopy and immunohistochemistry, we characterized the only two cases of ECT found in our institutional files over a period of 20 years. Both tumors were classified as type AB-thymoma. Neoplastic cells expressed cytokeratins but not CD5. Non-neoplastic T-lymphocytes were positive for CD3 and CD5. Lymphocytes expressed CD1a in only one case. One tumor breached the capsule and had positive surgical margins. For this patient, adjuvant radiotherapy was given. The other patient has had an uneventful follow-up for 20 years with no other therapy than surgery. Both cases of ECT showed identical histomorphological and immunohistochemical features of type AB-thymomas originating in the thymus. Short follow-up precludes conclusion on the implication of positive margins in conjunction with adjuvant radiotherapy for one of the patients presented herein.

Keywords: Ectopic cervical thymoma, Neck, Thymoma, Ectopic

Introduction

Ectopic thymoma (ET) is a rare tumor thought to originate from ectopic rests of thymic tissue caused by defective migration of the embryonic thymus [1]. ET has been reported in a variety of sites such as the neck (ectopic cervical thymoma, ECT) [2–9], chest wall [10], pleura [11], lung [12] and heart [13]. Among these ectopic sites, the cervical region appears to be one of the most frequent locations, where close proximity to the thyroid frequently results in a mistaken clinical impression of a primary thyroid neoplasm. ECT most commonly presents as an enlarging neck mass, although one case of ECT with myasthenia gravis as the presenting symptom is on record [7]. In this paper, we present the clinicopathological features of two cases of ECT seen in our institution over the course of two decades.

Materials and Methods

After diagnosing a recent case of ECT (Case 1), we searched the institutional file of the Department of Pathology at our institution (National University Hospital, Singapore) from 1989 to 2009 for additional cases. One case of ECT (Case 2) was found, retrieved and reviewed. The tissue was fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin and 4 μm thin sections were cut and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. An immunohistochemical study was performed using commercially available antibodies (cytokeratin cocktail—MNF116, cytokeratin (CK) 14, CD3, CD5 and CD1a) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

Case 1

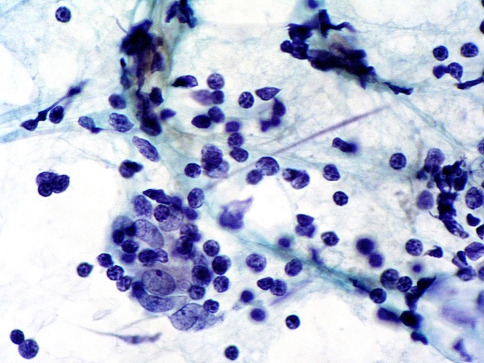

A 56-years-old previously healthy man presented with a 1-year history of an enlarging mass in the left thyroid region. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology showed an abundant small lymphoid population. Of note, no follicular cells or definite epithelial cells were identified. Very rare groups of cells with oval nuclei and slightly more abundant cytoplasm could be discerned in close association with the lymphocytes (Fig. 1), and these were interpreted as possible follicular dendritic cells. The FNA was reported as suspicious for lymphocytic thyroiditis. A left hemithyroidectomy was subsequently performed.

Fig. 1.

Case 1. Fine needle aspiration cytology showing a small lymphocytic population with a group of larger cells with oval nuclei and more abundant cytoplasm (×600)

Grossly, an encapsulated lobulated mass measuring 5.0 cm in greatest dimension was present external to but attached to the middle pole of the left hemithyroid (Fig. 2). The cut surface of the mass was tan-colored with no areas of necrosis.

Fig. 2.

Gross picture of a surgical specimen illustrating relation of tumor to the left thyroid lobe (Case 1). The thyroid is on the left side

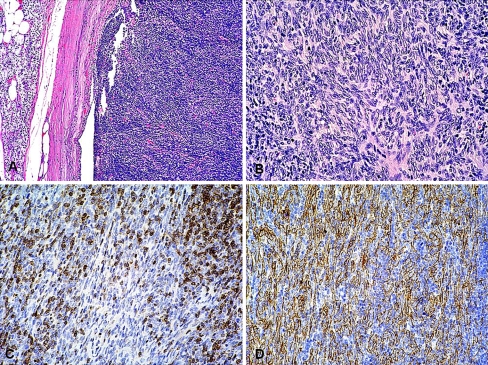

Microscopically, the tumor showed a biphasic pattern with regions of lymphocyte-rich areas admixed with lymphocyte-poor spindle cell areas, the former predominating (Fig. 3a). The spindle cells had a uniform and bland appearance with minimal cytologic atypia (Fig. 3b). Mitotic activity was low with less than 1 mitotic figure/10 high power fields (hpf. 400×). In the immunohistochemical study, the lymphocytes were positive for CD1a (Fig. 3c), CD3 and CD5 focally, while the spindle cells were positive for cytokeratins (Fig. 3d) and CK14, and negative for CD5. The tumor was diagnosed as a type AB thymoma. Although mostly encapsulated, the tumor breached the fibrous capsule in several areas. A thin rim of parathyroid tissue was present external to the capsule (Fig. 3a). The thyroid was unremarkable and was not infiltrated by the thymoma. Because of positive surgical margins, postoperative radiotherapy was given. The case was recently diagnosed and hence no meaningful follow-up is available.

Fig. 3.

Case 1. Photomicrographs (Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections). a Encapsulated tumor with a predominant lymphocyte-rich component. A rim of normal parathyroid tissue is present external to the capsule on the left (×100). b Lymphocyte-poor spindle cell area. The spindle cells show minimal cytologic atypia (×200). The Immunohistochemical study shows c positive reaction for CD1a in non-neoplastic lymphocytes and d positive reaction for cytokeratins (MNF116) in neoplastic cells (×200)

Case 2

A 35-years-old previously healthy female presented with a 9-months history of an enlarging right mid-cervical mass that was resected. Grossly, the tumor had a fleshy appearance and measured 6.0 cm in greatest dimension.

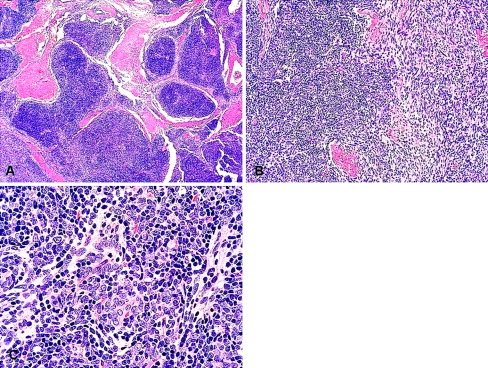

Microscopically, the tumor was composed of an intimate admixture of lymphocytes with a spindled and polygonal-epithelioid cell population (Fig. 4a–c). Both the spindled and epithelioid cells contained plump vesicular nuclei and were arranged in short intersecting fascicles, focally showing a storiform pattern. No high-grade atypia was present. The mitotic index was low with less than 1 mitotic figure/10 hpf. The neoplastic tissue was intersected by dense fibrous bands imparting a nodular appearance. Gland-like cystic spaces were present in the fibrous stroma, but no true glandular differentiation was present. The tumor was diagnosed as a type AB thymoma. The immunohistochemical study showed the lymphocytes to be positive for CD3 and CD5 focally, and negative for CD1a. The neoplastic (both spindled and epithelioid) cells were positive for cytokeratins (MNF116), CK14 and negative for CD5. The patient is alive and well with no recurrence 20 years after the surgical excision.

Fig. 4.

Case 2. Photomicrographs (Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections). a Lobulated, organoid tumor intersected by thick fibrous bands (×40). b Transition between lymphocyte-rich areas with predominantly spindle cell areas (×200). c Spindled to epithelioid neoplastic epithelial cells intimately admixed with lymphocytes (×400)

Discussion

Although the rare existence of thymic neoplasms occurring outside the thymus has been known for at least half a century [14–18], the exact incidence of various subtypes of thymoma is not known, particularly as defined by the 1999/2004 WHO classification system. In a paper from 1991, Chan and Rosai compiled eleven previously published cases of ECT (of which they reviewed four cases) and added five cases of their own which to date constitute the largest number of cases with clinicopathologic data published in the English literature [3]. This paper was published prior to the 1999 WHO Classification of thymic epithelial tumors. Since then, fewer than twenty cases of ECT have been published [2, 4–9, 19–25].

Table 1 provides a list of the various reported subtypes as defined by the 1999/2004 WHO classification system where known. From this, it appears that the general distribution parallels that of mediastinal thymomas, where type AB thymomas represent one of the more common subtypes [26]. One interesting observation is the marked female predominance in ECT [3], which differs from the demographics of the mediastinal thymomas where there is only a slight female predominance [26].

Table 1.

Previously reported ectopic cervical thymomas that have been classified according to WHO 2004

| Reference | Patient gender | Site | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al. [5] | Female | Anterior neck mass | AB |

| Cohen et al. [22] | Female | Intrathyroidal | AB |

| Mende et al. [6] | Male | Left cervical region related to the parotid | Micronodular |

| Gerhard et al. [4] | Female | Anterior cervical region | A |

| Hsu et al. [8] | Female | Neck mass | AB |

| Choi et al. [7] | Female | Left hemithyroid mass | A |

From the literature, ECT appears to display the same histological and immunohistochemical features as its thymic counterparts [3–5, 7, 10, 22], and this was similarly true in our cases. The lack of CD5 expression in the neoplastic thymic epithelial cells is in line with previous reports that CD5 expression is seen predominantly in thymic carcinomas [27]. It is also known that the lymphoid cells in thymomas are predominantly T cells that, depending on their developmental stage, may or may not express CD1a [28, 29], a marker of immature thymocytes [30]. Particularly, it has been reported that CD1a expression in the thymocytes tends to be absent in type A (medullary) thymomas, while it is present in type AB (mixed) or B (cortical) thymomas [28, 29]. The presence (Case 1) and absence (Case 2) of CD1a expression is therefore consistent with the literature.

The histological and immunohistochemical parallels between mediastinal and ectopic thymic tumours are also true for some variants of thymic carcinomas (squamous and lymphoepithelioma-types) and carcinomas occurring in or around the thyroid gland showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE). This is in contrast to the thyroid neoplasm “spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation” (SETTLE) occurring in or near the thyroid gland of which no thymic counterpart has yet been described and more so to the enigmatic lesion ectopic cervical hamartomatous thymoma, which according to some authors has no relation to either the fully developed or embryonic thymus and is best classified as a biphasic neoplasm of branchial anlage derivation, hence being neither ectopic or hamartomatous nor a thymoma [31].

Given its rarity, although its histological features parallel that of mediastinal/thymic thymomas, ECT represents a diagnostic pitfall especially on a fine needle aspiration cytology or frozen section where a lymphomatous process or undifferentiated carcinoma may be suggested, depending on whether the lymphocytes predominate and the epithelial cells are inconspicuous or if the histological features are those of a B3-type thymoma displaying epithelial cells with large nuclei and mitotic activity and a minimal or absent lymphocytic component. In fact, in Case 1, even a retrospective analysis of the fine needle cytology slide revealed very rare groups of cells that could have represented thymic epithelial cells. The correct diagnosis or at least a suggestion thereof is facilitated by the awareness of the existence of this rare tumor and if in doubt the pathologist should perform a limited immunohistochemical study with cytokeratins and lymphoid markers including CD1a in order to establish its epithelial and not lymphomatous nature. A lymphoepithelial-type carcinoma displays both high-grade nuclear features and the lymphocytic component is composed of mature cells lacking the expression of CD1a present in the immature thymocytes in thymomas. ECT has previously been erroneously reported on FNA as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [14], malignant lymphoma [2], atypical lymphoproliferative process [22], T cell lymphoma [5], and on frozen section as a poorly differentiated carcinoma probably of squamous cell type [9]. This was also true in our Case 1 where the FNA diagnosis was a reactive lymphoid population raising the possibility of lymphocytic thyroiditis.

In conclusion, we present the clinicopathologic features of two cases of ectopic cervical thymoma, the rarity of which is substantiated by the fact that these two cases were the only examples we found in our institutional files over a time period of 20 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor K. Shanmugaratnam for providing Case 2, and Mr. Tan Tee Chok for providing the photomicrographs.

References

- 1.Tunkel DE, Erozan YS, Weir EG. Ectopic cervical thymic tissue: diagnosis by fine needle aspiration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:278–281. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0278-ECTT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh YL, Ko YH, Ree HJ. Aspiration cytology of ectopic cervical thymoma mimicking a thyroid mass. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1167–1171. doi: 10.1159/000332107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan JK, Rosai J. Tumors of the neck showing thymic or related branchial pouch differentiation: a unifying concept. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:349–367. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerhard R, Kanashiro EH, Kliemann Cm CM, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of ectopic cervical spindle-cell thymoma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:358–362. doi: 10.1002/dc.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang ST, Chuang SS. Ectopic cervical thymoma: a mimic of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:633–635. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mende S, Moschopulos M, Marx A, et al. Ectopic micronodular thymoma with lymphoid stroma. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:397–399. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0961-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi H, Koh SH, Park MH, et al. Myasthenia gravis associated with ectopic cervical thymoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1393–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu IL, Wu MH, Lai WW, et al. Cervical ectopic thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1658–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mourra N, Duron F, Parc R, et al. Cervical ectopic thymoma: a diagnostic pitfall on frozen section. Histopathology. 2005;46:583–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai KR, Thonse VR, Azadeh B, et al. Ectopic thymoma of the chest wall. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:9–11. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2004.092122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higashiyama M, Doi O, Kodama K, et al. Ectopic primary pleural thymoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1996;26:747–750. doi: 10.1007/BF00312100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myers PO, Kritikos N, Bongiovanni M, et al. Primary intrapulmonary thymoma: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller DV, Tazelaar HD, Handy JR, et al. Thymoma arising within cardiac myxoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1208–1213. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000158398.65190.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin JM, Randhawa G, Temple WJ. Cervical thymoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:354–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins AW, Peacock JA. Case report: cervical thymoma. J Med Soc N J. 1985;82:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamashita H, Murakami N, Noguchi S, et al. Cervical thymoma and incidence of cervical thymus. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1983;33:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1983.tb02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bothra R, Dahiya SL, Treisman E. Cervical thymoma. Int Surg. 1975;60:301–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sease CI. Cervical thymoma; a case report. Va Med Mon. 1918;83:345–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramdas A, Jacob SE, Varghese RG, et al. Ectopic cervical thymoma—the great mimic: a case report. Ind J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50:553–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakshi J, Ghosh S, Pragache G, et al. Ectopic cervical thymoma in the submandibular region. J Otolaryngol. 2005;34:223–226. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.34401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagasawa K, Takahashi K, Hayashi T, et al. Ectopic cervical thymoma: MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:262–263. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.1.1820262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen JB, Troxell M, Kong CS, et al. Ectopic intrathyroidal thymoma: a case report and review. Thyroid. 2003;13:305–308. doi: 10.1089/105072503321582132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponder TB, Collins BT, Bee CS, et al. Diagnosis of cervical thymoma by fine needle aspiration biopsy with flow cytometry. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:1129–1132. doi: 10.1159/000327119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanka KP, Sarin B, Prasad V, et al. Benign cervical thymoma masquerading as a malignant thyroid nodule. Clin Nucl Med. 2002;27:862–864. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapoport A, Dias CF, Freitas JP, et al. Cervical thymoma. Sao Paulo Med J. 1999;117:132–135. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31801999000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jong WK, Blaauwgeers JL, Schaapveld M, et al. Thymic epithelial tumours: a population-based study of the incidence, diagnostic procedures and therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tateyama H, Eimoto T, Tada T, et al. Immunoreactivity of a new CD5 antibody with normal epithelium and malignant tumors including thymic carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:235–240. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexiev BA, Drachenberg CB, Burke AP. Thymomas: a cytological and immunohistochemical study, with emphasis on lymphoid and neuroendocrine markers. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hattori H, Tateyama H, Tada T, et al. PE-35-related antigen expression and CD1a-positive lymphocytes in thymoma subtypes based on Muller-Hermelink classification. An immunohistochemical study using catalyzed signal amplification. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:20–27. doi: 10.1007/PL00008194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Res P, Blom B, Hori T, et al. Downregulation of CD1 marks acquisition of functional maturation of human thymocytes and defines a control point in late stages of human T cell development. J Exp Med. 1997;185:141–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Michal M, et al. Ectopic hamartomatous thymoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 21 cases with data supporting reclassification as a branchial anlage mixed tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1360–1370. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000135518.27224.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]