The serine/arginine-rich proteins (SR proteins) constitute a family of predominantly nuclear RNA-binding proteins that are present in all metazoan organisms and in plants. The first SR protein was identified nearly 20 years ago as an essential pre-mRNA splicing factor that could also influence alternative splicing in human cell extracts, and was found to have sequence features similar to genetically defined splicing regulators in Drosophila (Ge et al. 1991; Krainer et al. 1991). Specifically, it contained two N-terminal RNP-type RNA-binding domains (RBDs; also known as an RNA recognition motif [RRM]), and a C-terminal region enriched in Arg–Ser dipeptides (RS domain). It was soon realized that a family of SR proteins exists in mammals that are characterized by one or two N-terminal RBDs and a C-terminal RS domain (Fu and Maniatis 1992; Zahler et al. 1992). The SR proteins have since been extensively studied in several species, and found to play important roles in splicing, both as general splicing factors and as regulators of alternative splicing. Unexpectedly, studies during the past decade have extended the role of SR proteins to a diverse set of additional cellular processes, including mRNA nuclear export, mRNA stability and quality control, translation, maintenance of genomic stability, oncogenic transformation, and likely others (Huang and Steitz 2005; Long and Cáceres 2009; Zhong et al. 2009). It is thus apparent that SR proteins play multiple important roles in the control of gene expression.

Despite the importance of SR proteins in these diverse cellular functions, a precise definition of what is an SR protein has been lacking, and nomenclature for established SR proteins has been confusing. Criteria for inclusion in the SR protein family have included sequence features, function in an in vitro splicing assay, and reactivity with a phospho-specific monoclonal antibody. Likewise, SR protein names have been based on function, apparent molecular weight, human gene name, and, in one case, an identifying antibody. However, there are many other proteins that share some but not all of these features, such as an RS domain, one or more RBDs, and a role in splicing, yet they do not belong to the same family.

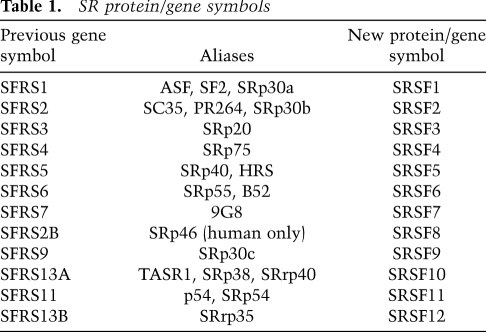

To clarify the identity of the SR proteins, and to rationalize nomenclature, we propose both a simple definition of SR proteins and a unified nomenclature. SR proteins will be defined based entirely on their sequence properties. We define an SR protein as any protein with the following minimal attributes: one or two N-terminal RBDs (PF00076), followed by a downstream RS domain of at least 50 amino acids with >40% RS content, characterized by consecutive RS or SR repeats. Searching the Uniprot database, we found 160 human proteins with only one (107 proteins) or two (53 proteins) RBDs. Fifty-one of these had an RS domain, but in only 16 of these proteins was the RS domain downstream from and nonoverlapping with the RBD(s). Clustering of these 16 proteins based on RS and RBD positional and compositional features resulted in three different groups. The proteins from group 1 (formerly SFRS1, SFRS4, SFRS5, SFRS6, and SFRS9) (see Table 1) have two RBDs, including an invariant and evolutionarily conserved SWQDLKD heptapeptide motif in the second RBD. In contrast, proteins from groups 2 (SFRS12, CPSF7, RBMX2, and SR140) and 3 (formerly SFRS13A, SFRS11, SFRS2B, SFRS2, SFRS3, SFRS7, and SFRS13B) have a single RBD lacking the SWQDLKD motif. The RBDs in proteins from group 2 are more divergent from the RBD consensus, compared with the other two groups; in addition, this group includes two proteins (CPSF7 and RBMX2) with no known role in pre-mRNA splicing. We therefore did not include the group 2 proteins in the SR protein family. This strict definition yields 12 SR proteins in humans, and these are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

SR protein/gene symbols

The new nomenclature is based on the root “SRSF” (SR splicing factor) followed by the numbers 1–12. This nomenclature is similar to the current Human Genome Organization names for SR protein genes, which also will be changed so that protein and gene names are identical (see Table 1). The numbers 1–12 were assigned to match as closely as possible the existing gene nomenclature, which in turn reflects the chronological order in which the genes/proteins were discovered. The proposed nomenclature is based on human proteins, but will be applicable to the orthologs in other vertebrate organisms. Other species—including flies, worms, and plants—will retain, for the time being, the current names assigned to SR proteins in those species, although we understand an effort by the plant SR protein community to standardize the nomenclature in plants is under way.

The proposal presented here both establishes rules for the definition of SR proteins and also provides a simple, unified nomenclature that applies to SR proteins and genes. This nomenclature should avoid confusion in the definition and naming of SR proteins and facilitate communication between scientists inside and outside the SR protein/splicing field.

Notes

The following scientists have endorsed the definitions and nomenclature described here: Göran Akusjärvi, Manuel Ares, Francisco Baralle, Andrea Barta, Karen Beemon, Giuseppe Biamonti, Douglas Black, Benjamin Blencowe, Tom Blumenthal, Christiane Branlant, Javier Cáceres, Luca Cartegni, Benoit Chabot, Lawrence Chasin, Thomas Cooper, Xiang-Dong Fu, Mariano Garcia-Blanco, Gourisankar Ghosh, Brenton Graveley, Michael Green, Masatoshi Hagiwara, Richard Harland, Klemens Hertel, Alberto Kornblihtt, John Lis, Javier Lopez, William Mattox, Stephen Mount, Karla Neugebauer, Timothy Nilsen, James Patton, Robin Reed, Donald Rio, Jeremy Sanford, Ruth Seal, Phillip Sharp, David Spector, Joan Steitz, James Stévenin, Jamal Tazi, Juan Valcárcel, Lars Wieslander, Stuart Wilson, Jane Wu, Alan Zahler, and Zhi-Ming Zheng.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Martin Akerman for help with bioinformatics analysis, and would like to acknowledge Ruth Seal (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee), James Stévenin, and Luca Cartegni for specific suggestions concerning the nomenclature.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1934910.

References

- Fu XD, Maniatis T 1992. Isolation of a complementary DNA that encodes the mammalian splicing factor SC35. Science 256: 535–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Zuo P, Manley JL 1991. Primary structure of the human splicing factor ASF reveals similarities with Drosophila regulators. Cell 66: 373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Steitz JA 2005. SRprises along a messenger's journey. Mol Cell 17: 613–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krainer AR, Mayeda A, Kozak D, Binns G 1991. Functional expression of cloned human splicing factor SF2: Homology to RNA-binding proteins, U1 70K, and Drosophila splicing regulators. Cell 66: 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JC, Cáceres JF 2009. The SR protein family of splicing factors: Master regulators of gene expression. Biochem J 417: 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahler AM, Lane WS, Stolk JA, Roth MB 1992. SR proteins: A conserved family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. Genes Dev 6: 837–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XY, Wang P, Han J, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD 2009. SR proteins in vertical integration of gene expression from transcription to RNA processing to translation. Mol Cell 35: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]