Abstract

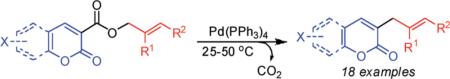

Allyl esters of 3-carboxylcoumarins undergo facile decarboxylative coupling at just 25–50 °C. This represents the first extension of decarboxylative C–C bond-forming reactions to the coupling of aromatics with sp3-hybridized electrophiles. Finally, the same concept can be applied to the sp2–sp3 couplings of pyrones and flavones. Thus, a variety of biologically important heteroaromatics can be readily functionalized without the need for strong bases or stoichiometric organometallics that are typically required for more standard cross-coupling reactions.

In recent years, significant effort has been devoted to the development of decarboxylative couplings that allow C–C bond forming cross-couplings without the need for preformed organometallics.1–3 In avoiding preformed organometallic re-agents, decarboxylative couplings often avoid the use of highly basic reaction conditions and the production of stoichiometric metal waste.1c One remarkable example is the decarboxylative biaryl synthesis developed by Gooβen.2 For all its potential utility, such sp2–sp2 couplings require decarboxylative metalation of sp2-hybridized carbons which is a relatively high-energy process that utilizes copper cocatalysts at 120–170 °C.2a,b A similar, cocatalyst free, decarboxylative coupling of heteroaromatics was also reported to occur at 150 °C.2c Thus, these promising reactions could still benefit from the development of more mild conditions for the cross-coupling. In addition, the decarboxylative coupling of aromatics and heteroaromatics has not been extended to sp2–sp3 couplings,1b,4 which would dramatically expand the structures that can be synthesized by decarboxylative arylation. Herein we report a palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation of coumarins that proceeds under exceptionally mild conditions.

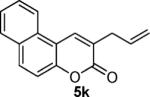

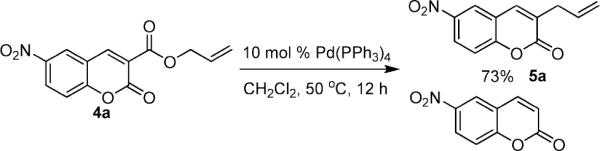

In looking for scaffolds on which to develop decarboxylative allylation of aromatic nucleophiles, we were immediately drawn to coumarins. Coumarins are privileged structures in biological chemistry, and numerous pharmaceuticals are based on development of this basic scaffold (Figure 1).5 Of these, warfarin (1) is the most well-known of a class of 3-alkyl coumarins used as anticoagulants. In principle, a decarboxylative allylation of coumarins may provide access to compounds like warfarin and also allow the synthesis of a wide variety of 3-alkylcoumarins for biological screening.

Figure 1.

Biologically active 3-alkyl coumarins.

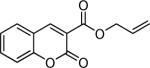

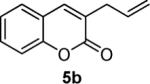

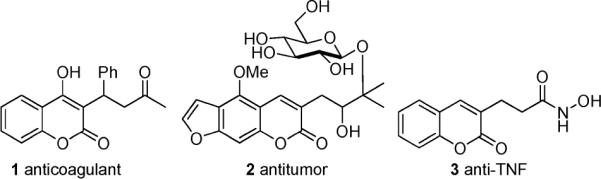

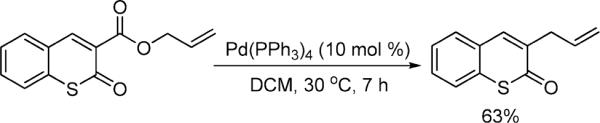

To begin, 4a was synthesized and treated with Pd(PPh3)4 in dry CH2Cl2 (Scheme 1). It was gratifying to find the reaction went to 100% conversion, allowing 3-allylcoumarin 5a to be isolated in 73% yield. In addition to product (5a), the reaction forms ca. 10% 6-nitrocoumarin, which results from protonation of a putative coumarin anion equivalent.6 It is particularly noteworthy that the decarboxylative metalation took place at just 50 °C. While decarboxylation of 3-carboxycoumarins can be effected by heating with strong acid or base, decarboxylative metalation under neutral conditions is difficult. For example, copper-catalyzed decarboxylation of a related 2-carboxycoumarin takes place at 248 °C in refluxing quinoline.6,7 Moreover, the allylation took place without the need for preformed organometallics that are typically required for the allylation of sp2 carbons,8,9 and it is more efficient than typical syntheses of 3-allylcoumarins.10

Scheme 1.

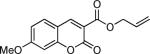

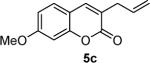

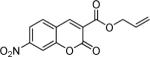

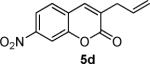

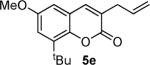

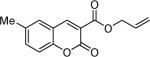

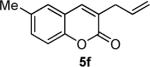

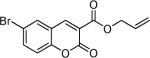

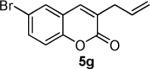

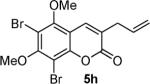

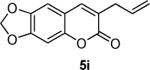

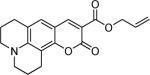

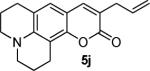

Next, a range of coumarins were subjected to our standard conditions for the coupling. As can be seen in Table 1, the yields of the coupling are generally good. The reaction is compatible with electron-donating and electron-withdrawing functional groups. This fact argues against simple electrophilic allylation of the coumarin.11 While coumarins with oxygen donors are excellent substrates, an amine-containing substrate (entry 9) provides a relatively low yield of product. Importantly, aryl bromides are tolerated, allowing tandem reactions involving decarboxylative coupling and standard cross-coupling chemistry. Lastly, a thiocoumarin substrate reacts similarly to the coumarin substrate, providing a 63% yield of 3-allyl thiocoumarin (Scheme 2).

Table 1.

Decarboxylative Coupling of Coumarins

Isolated yield using 10 mol % of Pd(PPh3)4, 50 °C, 12–15 h.

At room temperature.

Scheme 2.

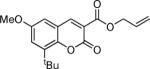

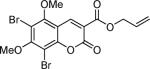

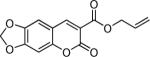

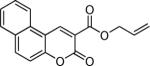

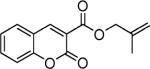

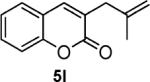

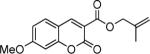

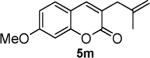

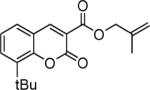

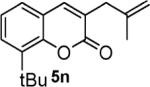

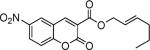

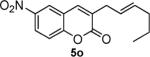

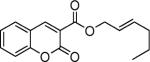

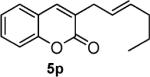

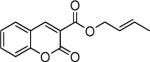

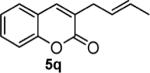

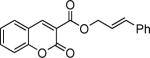

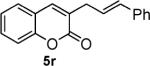

Next, we turned our attention to the investigation of the coupling of substituted allyl electrophiles with coumarins (Table 2). The coupling of 2-methallyl alcohol derivatives proceeds smoothly and provides products in somewhat higher yields than those without methallyl substituents (entries 1–3). Importantly, the chemistry is also compatible with 3-alkyl-substituted allyl groups (entries 4–6). This is particularly noteworthy because the coupling is the formal allylation of a very basic vinyl anion. Typically, such strong bases simply induce elimination of the π-allyl palladium intermediates.12

Table 2.

Decarboxylative Coupling of Substituted Allylic Esters

| entry | substrate | time (h) | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

12 |

|

82 |

| 2 |

|

16 |

|

87 |

| 3 |

|

10 |

|

78 |

| 4 |

|

12 |

|

53 |

| 5 |

|

12 |

|

66 |

| 6 |

|

15 |

|

42a |

| 7 |

|

12 |

|

81 |

Isolated as a 94:6 mixture of linear:branched regioisomers.

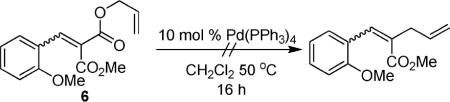

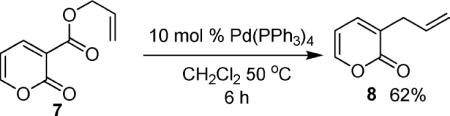

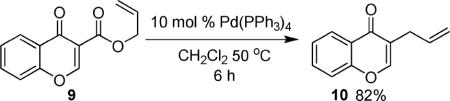

In the interest of exploring the features of the coumarin that allow decarboxylative coupling under such mild conditions, several experiments were performed. First, an acyclic analogue of the coumarin (6) was subjected to the standard reaction conditions for decarboxylative allylation of coumarins, and it did not produce any product (eq 1). While the reaction with the acyclic derivative failed, pyrone (7) reacts to form the product of decarboxylative coupling (8) under identical conditions to those used in the coumarin coupling (eq 2).13 Thus, the benzenoid ring of the coumarin is not required for reactivity. Lastly, the isomeric chromone derivative 9 provided coupling product (10) in good yield (eq 3), showing that the concept of decarboxylative allylation extends to heteroaromatics other than coumarins.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

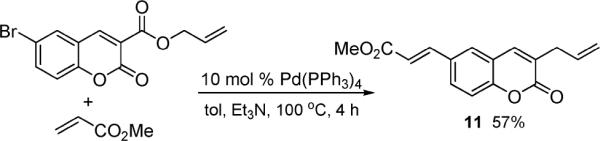

While decarboxylative couplings are often used in lieu of standard cross-coupling reactions that are more costly or wasteful,1a,3 decarboxylative couplings are oftentimes complementary to standard palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions. For instance, the decarboxylative sp2–sp3 coupling reported herein can be readily utilized in a tandem decarboxylative allylation/Heck olefination sequence to provide coumarin 11 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Decarboxylative Coupling/Heck Reaction

In conclusion, we have developed an exceptionally mild decarboxylative sp2–sp3 coupling that results in the allylation of pharmacologically relevant oxygenated heteroaromatics. Continuing studies are aimed at elucidating the mechanism of this transformation in hopes of defining the reasons that decarboxylative couplings of coumarins and related heteroaromatics are so facile.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM079644) and the KU Chemical Methodologies and Library Development Center of Excellence (P50 GM069663).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Shimizu I, Yamada T, Tsuji J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980:3199. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuda T, Chujo Y, Nishi S.-i., Tawara K, Saegusa T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6381. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rayabarapu DK, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13510. doi: 10.1021/ja0542688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Waetzig SR, Rayabarapu DK, Weaver JD, Tunge JA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4138. doi: 10.1021/ja070116w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Weaver JD, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4657. doi: 10.1021/ol801951e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Mohr JT, Behenna DC, Harned AW, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6924. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Trost BM, Bream RN, Xu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3109. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Goossen LJ, Deng G, Levy LM. Science. 2006;313:662. doi: 10.1126/science.1128684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goossen LJ, Zimmermann B, Knauber T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7103. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Forgoine P, Brochu MC, St-Onge M, Thesen KH, Bailey MD, Bilodeau F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11350. doi: 10.1021/ja063511f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Myers AG, Tanaka D, Mannion MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11250–11251. doi: 10.1021/ja027523m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka D, Romeril SP, Myers AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10323. doi: 10.1021/ja052099l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).The decarboxylative allylation of silylenol ethers has been reported. Tsuji J, Ohashi Y, Minami O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:2397.. Snider BB, Buckman BO. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:4883.. Coates RM, Sandefur LO, Smillie RD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:1619..

- (5).(a) Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:893. doi: 10.1021/cr020033s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Estevez-Craun A, Gonzalez AG. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997:465. doi: 10.1039/np9971400465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ngameni B, Touaibia M, Patnam R, Belkaid A, Sonna P, Ngadjui BT, Annabi B, Roy R. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2573. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chun K, Park S-K, Kim HM, Choi Y, Kim M-H, Park C-H, Joe B-Y, Chun TG, Choi H-M, Lee H-Y, Hong SH, Kim MS, Nam K-Y, Han G. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:530. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Worden LR, Kaufman KD, Weis JA, Schaaf TK. J. Org. Chem. 1969;34:2311. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Adams R, Bockstahler TE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:5346. [Google Scholar]; (b) Posakony J, Hirao M, Stevens S, Simon JA, Bedalov A. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2635. doi: 10.1021/jm030473r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cross-couplings of coumarins: Zhang L, Meng T, Fan R, Wu J. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7279. doi: 10.1021/jo071117+.. Schiedel M-S, Briehn CA, Bauerle P. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002;653:200.. Wu J, Yun L, Yang Z. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:3642. doi: 10.1021/jo0102157..

- (9).Allylation of sp2-carbon nucleophiles: Kayaki Y, Koda T, Takao I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:4989. doi: 10.1021/jo030370g.. Del Valle L, Stille JK, Hegedus LS. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3019.. Kobayashi Y, Watatani K, Tokoro Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;29:7533.. Tseng CC, Paisley SD, Goering HL. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:2884..

- (10).(a) Ahluwalia VK, Prakash C, Gupta R. Synthesis. 1980:48. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mali RS, Tilve SG, Yeola SN, Manekar AR. Heterocycles. 1987;26:121. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Electrophilic allylation of coumarins is generally only successful with electron-rich coumarins, and the regioselectivity favors allylation of the benzenoid ring. Ramachandra MS, Subbaraju GV. Synth. Commun. 2006;36:3723.. Cairns N, Harwood LM, Astles DP. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1994:3101..

- (12).(a) Tsuji J, Yamakawa T, Kaito M, Mandai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:2075. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shimizu I. In: Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. Negishi E.-i., editor. Wiley; New York: 2002. p. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- (13).3-Allylpyrone was previously synthesized in comparable yield via stoichiometric copper coupling. Posner GH, Harrison W, Wettlaufer DG. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:5041..

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.