Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) has a crucial role in the onset of hemolysis-induced vascular injury and cerebral vasoconstriction. We hypothesized that TNF-α measured from brain interstitial fluid would correlate with the severity of vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). Methods and results: From a consecutive series of 10 aSAH patients who underwent cerebral microdialysis (MD) and evaluation of vasospasm by CT angiogram (CTA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA), TNF-α levels from MD were measured at 8-hour intervals from aSAH days 4–6 using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. An attending neuroradiologist blinded to the study independently evaluated each CTA and DSA and assigned a vasospasm index (VI). Five patients had a VI < 2 and 5 patients had a VI > 2, where the median VI was 2 (range 0–18). The median log TNF-α area under the curve (AUC) was 1.64 pg/mL*day (interquartile range 1.48–1.71) for the VI < 2 group, and 2.11 pg/mL*day (interquartile range 1.95–2.47) for the VI > 2 group (p < 0.01). Conclusion: In this small series of poor-grade aSAH patients, the AUC of TNF-α levels from aSAH days 4–6 correlates with the severity of radiographic vasospasm. Further analysis in a larger population is warranted based on our preliminary findings.

Keywords: Cerebral microdialysis, Delayed cerebral ischemia, Multimodality monitoring, Tumor necrosis factor-α, Vasospasm

1. Introduction

Vasospasm is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH).1,2 Angiographic vasospasm is detected in 50–70% of patients with aSAH and delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) secondary to vasospasm occurs in 19–46% of aSAH patients and 54% of poor-grade aSAH patients.3–8 In these patients, who are often comatose, clinical deterioration is frequently missed, resulting in silent infarction in up to 21% of patients, which is associated with a poor clinical grade and outcome.4,9–11 The management of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm remains one of the most important aspects of the clinical care of patients with aSAH in the acute period, as neurological deficits incurred due to DCI secondary to vasospasm can be more significant than those sustained from the original aneurysm rupture.2,12 If treatment is instituted early, vasospasm may be managed with noninvasive strategies such as hypervolemia, hypertension, and hemodilution (triple-H therapy) and endovascular strategies such as angioplasty or intra-arterial vasodilator therapy have also shown promise.13–20 Therefore, early detection of vasospasm is important for the successful management of aSAH. However, limitations of current diagnostic techniques and the need for rapid diagnosis warrant the development of alternative monitoring techniques, and methods to identify characteristic changes in brain physiology and metabolism preceding vasospasm.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that contributes to vascular oxidative stress evoked by hemolysis.21,22 Both animal and human studies have demonstrated a role for TNF-α in cerebral vasospasm.23,24 Mouse studies using knockouts of the TNF-α transduction system demonstrate that the recruitment of other inflammatory mediators believed to be involved in vasospasm (interleukin-1β and inductible nitric oxide synthase) is dependent on TNF-α expression.25,26 Rabbit studies have shown that inhibition of the same transduction system resolves basilar artery vasospasm in an SAH model.24 Evidence for the central role that TNF-α plays in cerebral vasospasm was best demonstrated by a mouse model in which hemolyzed blood was injected into the cisterna magna.22 In this study, vessel caliber was monitored by ultrasound, in a similar manner to human transcranial Doppler ultrasound. The mouse model demonstrated that the narrowed caliber of cerebral arteries were reversed by TNF-α inhibitors.

Similar studies have not been conducted in humans; however, there is still strong evidence that TNF-α plays a pivotal role in cerebral vasospasm. Small studies in humans have looked at aSAH patients with elevated transcranial flow velocities versus those with normal flow velocities, and TNF-α was elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with elevated flow velocities.23 Furthermore, the peak elevation of TNF-α in CSF occurred on post-bleed days (PBD) 4–6. Another study showed that TNF-α measured in CSF not only increased on PBD 4–10, corresponding to peak vasospasm time, but was also associated with a worse outcome.26

Recent studies have used intracerebral microdialysis (MD) to detect DCI secondary to vasospasm.27-9 Several authors report that characteristic changes in neurochemical markers measured by MD, such as lactate, pyruvate, and glycerol, are indicators of cerebral ischemia.28,30-5 Some authors suggest that these and other MD parameters are predictive of delayed ischemic neurological deficit secondary to vasospasm.28,31,32

We hypothesized that levels of TNF-α measured from intracerebral MD would correlate with the severity of vasospasm following aSAH. We studied a series of poor-grade aSAH patients who underwent multimodality brain monitoring including MD, and who also underwent angiographic evaluation for vasospasm. TNF-α levels from PBD 4–6 were obtained from intracerebral MD, and correlated with the severity of vasospasm on angiography.

2. Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 10 consecutive patients admitted to the neurological intensive care unit at Columbia University Medical Center between December 2007 and May 2009. Patients were admitted for severe brain injury secondary to aSAH and underwent cerebral MD as part of their clinical care; vasospasms were also evaluated by computed tomography angiogram (CTA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Patient care for aSAH, including routine management of cerebral vasospasms, conformed to guidelines established by the American Heart Association.36

Clinically, the suspicion for vasospasm and decision to pursue CTA or angiography was made by the attending neurointensivist. Other potential causes of clinical deterioration, such as hydrocephalus, re-bleeding, or seizures, were rigorously excluded. An attending neuroradiologist, blinded to patient outcomes and the study design, independently evaluated each CTA and DSA and assigned a vasospasm index (VI). The VI is scored 0–3, depending on spasm severity to the carotid, middle cerebral, anterior cerebral, posterior cerebral, and basilar arteries (range 0–27). The VI was calculated by summing the spasm severity for all 9 arteries. Vasospasms resulting in 0–25%, 25–50%, 50–75%, or > 75% vessel narrowing were assigned a VI scale of 0, 1, 2, or 3, respectively. The degree of vasospasm was based on comparison with the original cerebral angiogram obtained at the time of admission for aSAH. The patients were divided into 2 groups based on the median VI of 2.

Cerebral MD sampling has been described in detail previously.37 A CMA 106 MD perfusion pump (CMA Microdialysis®, Solna, Sweden) was used to perfuse the interior of the catheter with sterile artificial CSF (Na+ 148 mmol/L, Ca2+ 1.2 mmol/L, Mg2+ 0.9 mmol/L, K+ 2.7 mmol/L, Cl− 155 mmol/L) at a rate of 0.3 μL/min. Samples were collected every 60 min into microvials, and immediately analyzed at the bedside for glucose, lactate and pyruvate (mmol/L) with the CMA 600 analyzer (CMA Microdialysis®, Solna, Sweden). At least 1 hour passed after insertion of the probe before commencing sampling, to allow for normalization of changes due to probe insertion. The analyzer was automatically calibrated on initiation and every 6 hours using standard calibration solutions from the manufacturer. Quality controls at 3 different concentrations for each marker were performed daily.

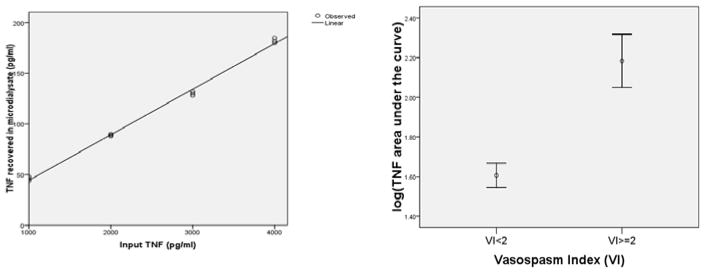

To determine the fractional recovery of TNF-α from MD, purified human TNF-α was added to 10 mL artificial CSF to make 4 concentrations of TNF-α: 1000 pg/mL, 2000 pg/mL, 3000 pg/mL, and 4000 pg/mL. A CMA 106 MD perfusion pump (CMA Microdialysis®; Solna, Sweden) was operated with different concentrations of TNF-α. Fractional recovery was calculated by plotting actual TNF-α concentration in the Petri dish versus recovered TNF-α concentration in the microdialysate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) recovered in microdialysate compared to input TNF-α. Recovery is about 4.5%. (B) Graphical representation of the Mann–Whitney relationship between TNF-α area under the curve and the vasospasm index (VI) showing that the relationship between recovery and input is linear.

For each of the 10 patients, TNF-α was measured from MD samples obtained at 8-hour intervals over aSAH days 4–6, totaling 9 measurements. TNF-α was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit for detection of human TNF-α, as described previously.38 PBD 4–6 were chosen because there is evidence that TNF-α does not change in the serum of aSAH patients from ictus to PBD 339, but does increase from PBD 4 to 10.26 The use of human samples was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

To calculate the area under the curve (AUC) of TNF-α over aSAH days 4–6, each patient’s TNF-α levels were log-transformed and graphed versus time, and this curve was integrated using the trapezoid rule: (t2 − t1)*[f(t2) + f(t1)]/2.40 Comparison of TNF-α AUC among vasospasm severity groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 16 software (SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean initial Hunt and Hess grade and modified Fisher scale were 4 ± 1 and 3 ± 1 (Table 1). CTA or DSA was performed between aSAH days 4 and 10 (median day 5). The median modified Rankin score at 3 months was 5 (range 3–6).

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

| Patient no. | Age (yrs)/Sex | Admission H + H grade | Fisher scale | Aneurysm location | aSAH day of CTA/angiogram | Vasospasm location | VI† | mRS score (3 mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57/F | 5 | 3 | ACoA | 8 | B ICA, B MCA, B ACA | 6 | 6 |

| 2 | 27/F | 5 | 3 | L ICA | 7 | None | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | 35/F | 4 | 4 | R VA | 10 | B ICA, L ACA, B MCA, B PCA, BA | 13 | 4 |

| 4 | 38/F | 4 | 3 | ACoA | 4 | B ICA | 2 | 6 |

| 5 | 65/M | 5 | 3 | R ICA | 9 | L ACA, BA | 2 | 5 |

| 6 | 42/F | 3 | 3 | ACoA | 5 | None | 0 | 3 |

| 7 | 65/F | 4 | 3 | L ICA | 5 | L ACA, L MCA | 2 | 5 |

| 8 | 30/M | 5 | 2 | L PCa | 4 | R ACA | 1 | 6 |

| 9 | 51/M | 2 | 4 | L MCA | 5 | None | 0 | 3 |

| 10 | 45/F | 5 | 4 | L MCA | 5 | L MCA | 1 | 3 |

The vasospasm index ranges from 0–27. ACA = anterior cerebral artery, ACoA = anterior communicating artery, aSAH = aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, B = bilateral, BA = basilar artery, CTA = CT angiogram, F = female, H + H = Hunt and Hess, ICA = internal cerebral artery, L = left, M = male, MCA = middle cerebral artery, mos = months, mRS = modified Rankin scale score, PCa = pericallosal artery, PCA = posterior cerebral artery, R = right, SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, VA = vertebral artery, VI = vasospasm index.

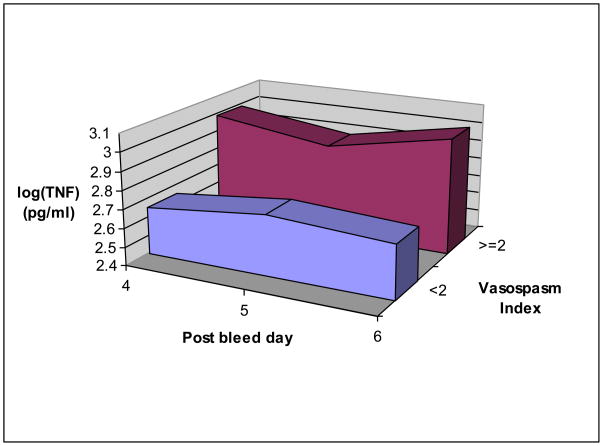

Five patients had a VI < 2 and 5 patients had a VI ≥ 2. Vasospasm involved the internal carotid arteries in 3 patients, anterior cerebral arteries (ACA) in 5 patients, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) in 4 patients, and the posterior cerebral artery in 1 patient. The median log TNF-α AUC was 1.64 (pg/mL)*day (interquartile range 1.48–1.71) for the VI < 2 group, and 2.11 (pg/mL)*day (interquartile range 1.95–2.47) for the ≥ 2 group (p < 0.01) The recovery of TNF-α from the microdialysate was 4.5% and the relationship between recovery and input is linear (Figs 1, 2).

Fig. 2.

The average of all tumor necrosis factor-α levels on subarachnoid hemorrhage days 4–6 in patients with a vasospasm index (VI) ≥ 2 versus those with a VI < 2.

4. Discussion

We demonstrated that increased levels of TNF-α in brain interstitial fluid between aSAH days 4 and 6 is significantly associated with worsened angiographic vasospasm (VI > 2, p<0.01). Previous work has demonstrated a central role for TNF-α in the development of cerebral vasospasm and an association with poor outcome.26,41 Intracerebral MD has shown promise in detecting characteristic changes in lactate, pyruvate, and glycerol in brain interstitial fluid during cerebral ischemia.42 There are several reasons why brain interstitial TNF-α, in particular, may be a sensitive marker for vasospasm severity. MD sampling occurs within the frontal white matter, typically in the anterior cerebral artery/middle cerebral artery watershed territory, and these samples may better represent the local neurochemical environment, compared to sampling from the entire CSF volume. Second, intracerebral MD is performed hourly, whereas CSF collection is typically performed daily; therefore, MD sampling offers much better temporal resolution to accurately detect TNF-α, a cytokine with a known half-life of 6–8 hours.43

There are several important limitations to our study. The small sample size restricts the interpretation of our findings. Furthermore, only radiographic vasospasm was assessed, not clinically symptomatic vasospasm, which may be of greater importance. In this series of primarily poor-grade patients, clinical deterioration was often difficult to detect, unreliable, or absent.

4. Conclusion

Intracerebral MD can be used to obtain brain interstitial fluid TNF-α concentrations. Further investigation into the relationship between brain interstitial TNF-α levels and cerebral vasospasm is warranted based on our preliminary findings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kassell NF, Boarini DJ. Cerebral ischemia in the aneurysm patient. Clin Neurosurg. 1982;29:657–65. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/29.cn_suppl_1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komotar RJ, Zacharia BE, Valhora R, et al. Advances in vasospasm treatment and prevention. J Neurol Sci. 2007;261:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charpentier C, Audibert G, Guillemin F, et al. Multivariate analysis of predictors of cerebral vasospasm occurrence after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:1402–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claassen J, Bernardini GL, Kreiter K, et al. Effect of cisternal and ventricular blood on risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the Fisher scale revisited. Stroke. 2001;32:2012–20. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hijdra A, van Gijn J, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Prediction of delayed cerebral ischemia, rebleeding, and outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1988;19:1250–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.10.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hop JW, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, et al. Initial loss of consciousness and risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:2268–71. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murayama Y, Malisch T, Guglielmi G, et al. Incidence of cerebral vasospasm after endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured aneurysms: report on 69 cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:830–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir B, Grace M, Hansen J, et al. Time course of vasospasm in man. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:173–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.2.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Frontera JA, et al. Prognostic significance of continuous EEG monitoring in patients with poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4:103–12. doi: 10.1385/NCC:4:2:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimoda M, Takeuchi M, Tominaga J, et al. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic infarcts from vasospasm in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: serial magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1341–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200112000-00010. discussion 8–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vespa PM, Nuwer MR, Juhasz C, et al. Early detection of vasospasm after acute subarachnoid hemorrhage using continuous EEG ICU monitoring. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;103:607–15. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claassen J, Peery S, Kreiter KT, et al. Predictors and clinical impact of epilepsy after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2003;60:208–14. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038906.71394.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badjatia N, Topcuoglu MA, Pryor JC, et al. Preliminary experience with intra-arterial nicardipine as a treatment for cerebral vasospasm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:819–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker FG, II, Ogilvy CS. Efficacy of prophylactic nimodipine for delayed ischemic deficit after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a metaanalysis. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:405–14. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.3.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biondi A, Ricciardi GK, Puybasset L, et al. Intra-arterial nimodipine for the treatment of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: preliminary results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1067–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott JP, Newell DW, Lam DJ, et al. Comparison of balloon angioplasty and papaverine infusion for the treatment of vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:277–84. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.2.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng L, Fitzsimmons BF, Young WL, et al. Intraarterially administered verapamil as adjunct therapy for cerebral vasospasm: safety and 2-year experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1284–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui C, Lau KP. Efficacy of intra-arterial nimodipine in the treatment of cerebral vasospasm complicating subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:1030–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassell NF, Peerless SJ, Durward QJ, et al. Treatment of ischemic deficits from vasospasm with intravascular volume expansion and induced arterial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:337–43. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keuskamp J, Murali R, Chao KH. High-dose intraarterial verapamil in the treatment of cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:458–63. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/3/0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cahill J, Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1341–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vecchione C, Frati A, Di Pardo A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates hemolysis-induced vasoconstriction and the cerebral vasospasm evoked by subarachnoid hemorrhage. Hypertension. 2009;54:150–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.128124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fassbender K, Hodapp B, Rossol S, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in subarachnoid haemorrhage: association with abnormal blood flow velocities in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001:534–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.4.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou ML, Shi JX, Hang CH, et al. Potential contribution of nuclear factor-kappaB to cerebral vasospasm after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rabbits. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007:1583–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoki T, Kataoka H, Shimamura M, et al. NF-kappaB is a key mediator of cerebral aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2007:2830–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathiesen T, Edner G, Ulfarsson E, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor-alpha following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:215–20. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarrafzadeh AS, Haux D, Lüdemann L, et al. Cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a correlative microdialysis-PET study. Stroke. 2004;35:638–43. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000116101.66624.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarrafzadeh AS, Sakowitz OW, Kiening KL, et al. Bedside microdialysis: a tool to monitor cerebral metabolism in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients? Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1062–70. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarrafzadeh AS, Sakowitz OW, Lanksch WR, et al. Time course of various interstitial metabolites following subarachnoid hemorrhage studied by on-line microdialysis. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2001;77:145–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6232-3_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enblad P, Valtysson J, Andersson J, et al. Simultaneous intracerebral microdialysis and positron emission tomography in the detection of ischemia in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:637–44. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frykholm P, Hillered L, Langstrom B, et al. Increase of interstitial glycerol reflects the degree of ischaemic brain damage: a PET and microdialysis study in a middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion primate model. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:455–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillered L, Persson L. Neurochemical monitoring of the acutely injured human brain. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1999;229:9–18. doi: 10.1080/00365519950185904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kett-White R, Hutchinson PJ, Al-Rawi PG, et al. Cerebral oxygen and microdialysis monitoring during aneurysm surgery: effects of blood pressure, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and temporary clipping on infarction. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:1013–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakowitz OW, Wolfrum S, Sarrafzadeh AS, et al. Relation of cerebral energy metabolism and extracellular nitrite and nitrate concentrations in patients after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1067–76. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulz MK, Wang LP, Tange M, et al. Cerebral microdialysis monitoring: determination of normal and ischemic cerebral metabolisms in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:808–14. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Jr, Batjer HH, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zielke HR, Zielke CL, Baab PJ. Direct measurement of oxidative metabolism in the living brain by microdialysis: a review. J Neurochem. 2009;109:24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crowther JR. ELISA. Theory and practice Methods Mol Biol. 1995;42:1–218. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-279-5:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Witkowska AM, Borawska MH, Socha K, et al. TNF-alpha and sICAM-1 in intracranial aneurismal rupture. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2009;57:137–40. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atkinson KA. An Introduction to Numerical Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayaraman T, Paget A, Shin YS, et al. TNF-alpha-mediated inflammation in cerebral aneurysms: a potential link to growth and rupture. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:805–17. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillered L, Persson L, Pontén U, et al. Neurometabolic monitoring of the ischaemic human brain using microdialysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1990;102:91–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01405420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selby P, Hobbs S, Viner C, et al. Tumour necrosis factor in man: clinical and biological observations. Br J Cancer. 1987;56:803–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]