Abstract

Clinical observations have suggested that ritanserin, a 5-HT2A/C receptor antagonist may reduce motor deficits in persons with Parkinson's Disease (PD). To better understand the potential antiparkinsonian actions of ritanserin, we compared the effects of ritanserin with the selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 and the selective 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 206553 on motor impairments in mice treated with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). MPTP-treated mice exhibited decreased performance on the beam-walking apparatus. These motor deficits were reversed by acute treatment with L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (levodopa). Both the mixed 5-HT2A/C antagonist ritanserin and the selective 5-HT2A antagonist M100907 improved motor performance on the beam-walking apparatus. In contrast, SB 206553 was ineffective in improving the motor deficits in MPTP-treated mice. These data suggest that 5-HT2A receptor antagonists may represent a novel approach to ameliorate motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: M100907, motor deficits, MPTP, ritanserin, SB 206553, serotonin

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor impairments, including rigidity, tremor, bradykinesia, and postural instability. These motor symptoms have been primarily attributed to the progressive degeneration of dopamine (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra and a concomitant loss of striatal DA (Lang and Luzano, 1998; Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Fahn, 2003; Nutt and Wooten, 2005).

The motor symptoms of PD are treated by dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) with administration of either L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (levodopa) or direct dopamine agonists. Unfortunately, most patients so treated develop motor fluctuations and abnormal involuntary movements (dyskinesias) after several years (Lang and Luzano, 1998; Obeso et al., 2000; Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Fahn, 2003; Nutt and Wooten, 2005). There is a clear need to identify non-dopaminergic drug targets to provide fewer side effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Clinical studies have suggested that serotonin-2 (5-HT2) receptor antagonists may be useful in the treatment of the motor symptoms of PD. For example, ritanserin, a mixed 5-HT2A/C receptor antagonist, has been shown to reduce bradykinesia and improve gait in PD patients (Henderson et al., 1992), as well as ameliorate neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism (Bersani et al., 1990). Lucas and coworkers (1997) showed that the reduction of neuroleptic-induced catalepsy in rats by ritanserin was independent of changes in DA dynamics. These actions of ritanserin may be related to the localization of striatal 5-HT2A receptors to corticostriatal and pallido-striatal neurons (Bubser et al., 2001), where they serve as heteroceptors to regulate glutamate release (Scruggs et al., 2003).

To explore the role of 5-HT2 receptors on motor dysfunction in parkinsonism, we used the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) model of parkinsonism in mice. MPTP treatment of susceptible species results in a marked depletion of striatal DA stores and loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra (Heikkila et al., 1984; Sundstrom et al., 1987; Stephenson et al., 2007). We assessed motor function of MPTP-treated mice using the open field test, rotarod apparatus, and the beam traversing task (Fernagut et al., 2004; Allbutt and Henderson, 2007; Quinn et al., 2007). We then compared the effects of mixed and subtype selective 5-HT2 receptor antagonists with the indirect dopamine agonist levodopa on MPTP-induced motor deficits.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice, 70-77 days of age at the start of experiments, were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were group housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room and maintained on a 12L:12D light-dark cycle (lights off at 1900h). Food and water were provided ad libitum. All studies were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and under the oversight of the Meharry Medical College Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug treatments

Mice were injected with 20 mg/kg (ip) MPTP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or saline every two hours for a total of four injections, resulting in a cumulative dose of 80 mg/kg; there was a mortality rate of 5% using this treatment protocol.

All behavioral tests were done three weeks after MPTP administration. Where indicated, animals were subjected to motor function tests 20 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of 15 mg/kg L-DOPA methyl ester (Sigma-Aldrich) with 12.5 mg/kg benserazide (Sigma-Aldrich), a peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitor. Serotonergic antagonists were injected intraperitoneally 30 min before behavioral testing. These included ritanserin (Sigma-Aldrich) and SB 206553 (Sigma-Aldrich), which were dissolved in saline containing 0.4% acetic acid and adjusted to pH 6.5-7.0 with NaOH (Leslie et al., 1993), and the selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, M100907 [(R-(+)-alpha-(2,3-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-[2-(4-fluorophenethyl)]-4-piperidinemethanol)]; Kehne et al., 1996), which was dissolved in 0.1 M tartaric acid solution which adjusted to pH 6.5-7.0 with NaOH. All injection volumes were 10 ml/kg. All mice received a single dose of either vehicle or an active pharmacological agent; animals did not receive different doses of the various drugs examined. Thus, all comparisons were between subjects. We chose a broad range of doses encompassing effective doses that can block the specific receptor. The doses of drugs used were based on the available literature (Leslie et al., 1993; Kehne et al., 1996; De Deurwaerdere et al., 2004) as well as pilot studies which showed that the selected doses did not alter general locomotor behavior.

Open Field Test

Each mouse was placed in an activity monitor measuring 27.3 cm × 27.3 cm (Med Associates, St. Albans VT) and locomotor activity and rearing (measured as interruptions of photobeams at different heights in the cage) were recorded in 10 min bins for 60 min.

Rotarod Test

Each mouse was placed in a separate lane of a rotarod (Med Associates, St. Albans VT) on a 5-cm diameter rotating cylinder at 5 rpm. The mice were first placed on the rubber covered cylinder and left for 30 s to habituate to the rod without rotation. The rotarod was started and brought slowly up to the required speed of 5 rpm. The performance was recorded as the mean latency to fall from the rod (up to 300 s) in four consecutive trials with a 5-min resting period between each trial.

Beam Walking Apparatus

The apparatus used in this experiment was a modification of that used by Allbutt and Henderson (2007). It consisted of a 1 cm square stainless steel beam of 105 cm in length. The beam was suspended 49 cm above the floor of the test chamber. Mice were habituated to the goal box for 3 minutes, then placed a distance of 10 cm from goal box. They were allowed to traverse the beam to the goal box. Upon successful traversal of the beam to the goal box at the 10 cm distance, mice were placed at increasing distances of 30, 50, and 80 cm from the goal box and trained to traverse the beam for one trial at each distance for two consecutive days. Mice able to traverse the full 80 cm length of the beam to the goal box within 60 seconds were considered to reach criterion. Three weeks post-MPTP treatment mice were subjected to three consecutive trials on the beam during which time they were videotaped. The number of footslips off the beam in each trial, and the mean number of hindlimb footslips during a three-trial session, were recorded (Dluzen et al., 2001; Fernagut et al., 2004; Strome et al., 2006; Allbutt and Henderson 2007; Quinn et al., 2007; Urakawa et al., 2007) by persons unaware of the treatment condition of the animals.

Regional monoamine concentrations

Separate groups of untreated animals were used to determine the effects of MPTP treatment on regional monoamine concentrations. Animals were sacrificed three weeks after saline or MPTP administration. This is the same time point that the behavioral studies were performed. These animals did not receive pharmacological agents. The tissues harvested for monoamine determination included the dorsal precommissural striatum, nucleus accumbens (including both core and shell), substantia nigra, and cerebellum. The tissues were dissected from 1.0 mm thick coronal slices (Deutch et al., 1985) and samples stored at -80° C until assayed. Regional concentrations of dopamine, serotonin, and their acidic metabolites were determined by HPLC-EC as previously described (Deutch and Cameron, 1992), with protein concentrations determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Statistical Analysis

Data on monoamine concentrations (ng amine/mg protein) in MPTP-treated and control animals were analyzed by Student's t-test; alpha levels (corrected for multiple comparisons) were set at 0.05. Two-way ANOVAs were used to analyze the behavioral effects of levodopa, ritanserin, M100907 and SB 206553, with post hoc tests when indicated by a significant main effect or interaction. Because baseline footslips did not vary across different experiments, the footslip data from the control groups were pooled.

Results

Behavioral Studies

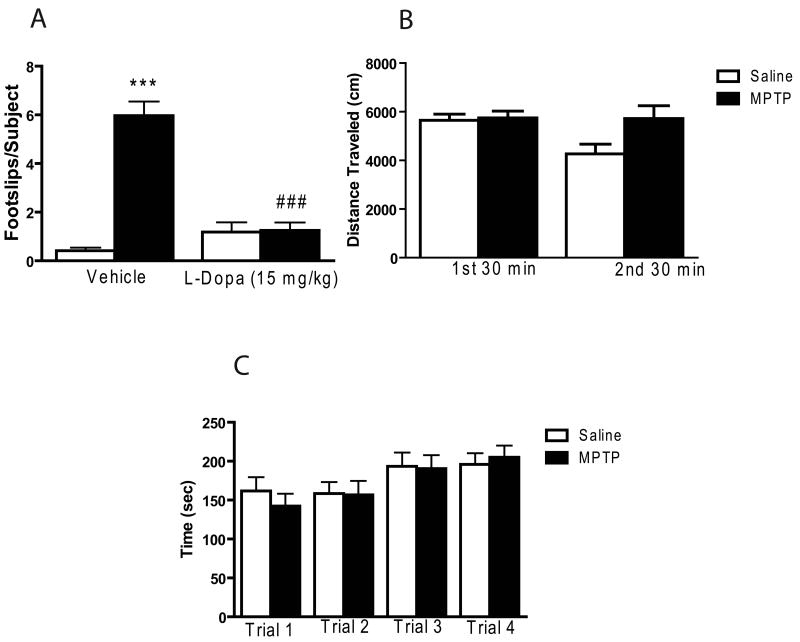

MPTP treatment did not result in a significant difference in locomotor activity, as measured in the open field, nor did it significantly impair rotarod performance (see Figure 1B and 1C). In contrast, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of MPTP treatment on the number of footslips as the mice traversed the beam in the beam walking task (overall F3,81 = 40.88, p < 0.001; MPTP treatment effect F1,81 = 29.86, p < 0.001; see Figure 1A). Post hoc tests demonstrated MPTP treatment caused a marked increase in the number of footslips (p < 0.001). The impaired performance on the beam walking task was completely reversed by levodopa (overall F3,81 = 40.88, p < 0.001; drug (levodopa) main effect F1,81 = 14.81, p < 0.001; treatment × drug interaction F1,81 = 28.43, p < 0.001; see Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Motor performance in MPTP-treated mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (A) MPTP treatment produced significant increase in the number of footslips. The number of footslips in MPTP-treated mice was decreased by L-DOPA when compared with saline-treated mice. Because baseline footslips did not vary across different experiments, the footslip data from the vehicle groups were pooled (Vehicle: n = 31/group; L-DOPA: n = 10/group). (B) MPTP treatment did not alter locomotor activity of MPTP-treated mice (n = 12) in the open field test when compared to saline-treated mice (n = 8). (C) Motor performance on the rotarod (n = 10/group). *** significantly different from saline-treated mice (P < 0.001); ### significantly different from MPTP-treated mice (P < 0.001), in two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc comparison.

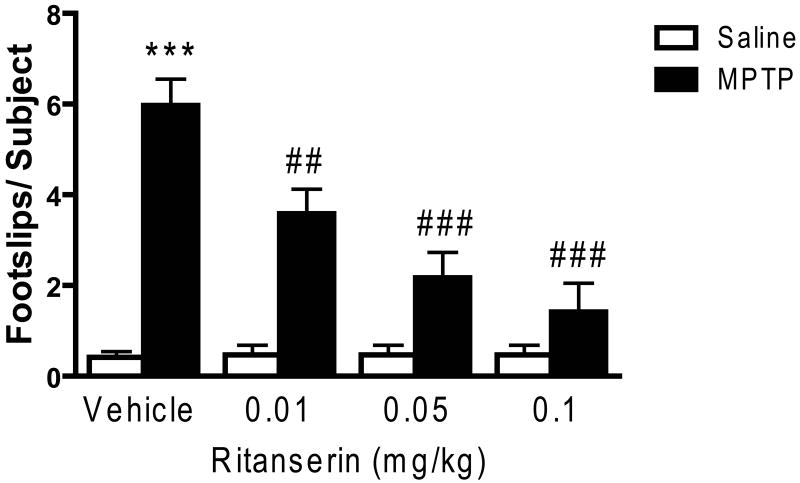

Ritanserin also resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the number of footslips as the mice traversed the beam (see Figure 2), with significant main effects on the MPTP treatment (F1,135 = 68.67, p < 0.001) and drug (F3,135 = 11.50, p < 0.001) conditions, as well as a significant MPTP condition × drug interaction (F3,135 = 12.05, p < 0.001). However, despite the fact that a significant improvement in performance was noted even at the lowest dose of ritanserin tested (0.01 mg/kg), at no dose did ritanserin completely reverse the performance deficit in beam walking (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ritanserin decreased the number of footslips in MPTP-treated mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Ritanserin produced dose-dependent attenuation of motor impairments exhibited by MPTP-treated mice on the beam-walking apparatus but had no effect on the performance of saline-treated mice. The footslip data from the vehicle groups were pooled (Vehicle: n = 31/group; Ritanserin: n = 12/group). *** significantly different from saline-treated mice (P < 0.001); ## significantly different from MPTP-treated mice (P < 0.01); ### significantly different from MPTP-treated mice (P < 0.001); in two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc comparison.

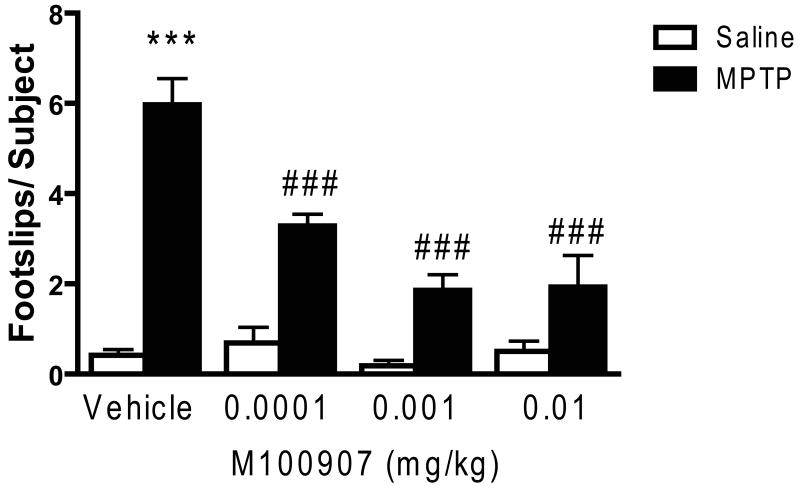

Results similar to those seen with ritanserin were obtained in testing the effects of M100907. Thus, ANOVA revealed significant MPTP treatment (F1,139 = 70.47, p < 0.001) and drug (F3,135 = 11.23, p < 0.001) main effects, as well as a significant interaction (F3,135 = 11.72, p < 0.001) (see Figure 3). Significant main effects were seen with the lowest dose tested (0.1 μg/kg), with no significant difference seen between the 1.0 and 10.0 μg/kg doses (see Figure 3). As was the case with ritanserin, M100907 did not completely reverse the MPTP-induced performance deficit (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

M100907 improved performance of MPTP-treated mice on the beam walking apparatus. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. M100907 dose-dependently reduced the number of footslips in MPTP-treated mice but had no effect on saline-treated mice. The footslip data from the vehicle groups were pooled (Vehicle: n = 31/group; M100907: n = 13/group). *** significantly different from saline-treated mice (P < 0.001); ### significantly different from MPTP-treated mice (P < 0.001), in two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc comparison.

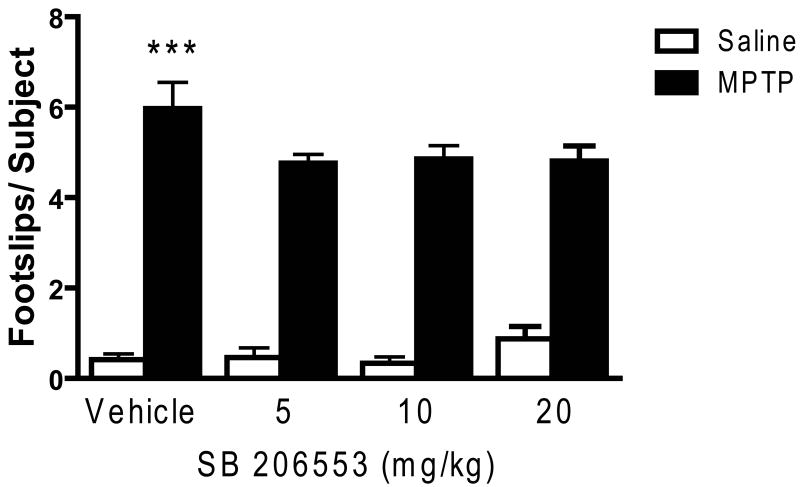

In contrast to the effects of ritanserin and M100907, the 5-HT2C antagonist SB 206553 did not significantly improve performance on the beam task (see Figure 4). Thus, although there was a significant MPTP treatment effect (F1,146 = 253.34, p < 0.001), no significant drug main effect was uncovered, nor was there a significant MPTP × drug interaction (F3,146 = 1.275; NS).

Figure 4.

SB 206553 failed to improve motor deficits in MPTP-treated mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. SB 206553 had no effect on footslips of both groups of mice (n = 10/group). The footslip data from the vehicle groups were pooled (Vehicle: n = 31/group; SB 206553: n = 13/group). *** significantly different from saline-treated mice (P < 0.001) in two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc comparison.

Neurochemical Assessment

MPTP treatment decreased striatal dopamine (DA) concentrations by 79% relative to saline-treated controls (see Table 1). Concentrations of the DA metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) were also significantly decreased, and consistent with a large but incomplete lesion of the striatal DA innervations. DA utilization (DOPAC/DA) was significantly increased (see Table 1). DA concentrations were also significantly lower in the nucleus accumbens and substantia nigra than in saline-injected control mice (Table 1), but no difference in cerebellar DA levels was uncovered. In contrast to the significant decreases in nigrostriatal DA levels, concentrations of serotonin did not differ significantly between MPTP-and saline-treated mice, nor were any differences in serotonin utilization (5-HIAA/5-HT) uncovered. Although MPTP treatment did not alter 5-HT levels in the striatum and nucleus accumbens, a significant decrease in 5-HT concentration and that of its metabolite 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) was seen in the substantia nigra (Table 1).

Table 1.

Levels of DA, 5-HT, and their metabolites, DOPAC and 5-HIAA measured by HPLC in brain regions of saline and MPTP-treated mice.

| Treatment | DA | DOPAC | DA Utilization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Striatum | Saline | 64.91±3.53 | 4.65±0.34 | 0.07±0.004 |

| MPTP | 13.66±1.37** | 1.37±0.12** | 0.10±0.006* | |

| S. Nigra | Saline | 3.39±0.36 | 1.05±0.07 | 0.32±0.01 |

| MPTP | 2.14±0.36* | 0.67±0.09* | 0.34±0.03 | |

| N. Accumbens | Saline | 14.07±0.54 | 2.36±0.16 | 0.17±0.01 |

| MPTP | 8.71±0.67** | 1.42±0.08** | 0.17±0.01 | |

| Cerebellum | Saline | 0.07±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.79±0.29 |

| MPTP | 0.05±0.03 | 0.01±0.01 | 1.63±0.84 | |

| 5-HT | 5-HIAA | 5-HT Utilization | ||

| Striatum | Saline | 1.07±0.14 | 0.59±0.02 | 0.63±0.08 |

| MPTP | 0.98±0.07 | 0.56±0.02 | 0.59±0.05 | |

| S. Nigra | Saline | 11.21±0.53 | 6.56±0.22 | 0.60±0.04 |

| MPTP | 9.05±0.74* | 4.87±0.45* | 0.54±0.04 | |

| N. Accumbens | Saline | 1.19±0.07 | 1.80±0.23 | 1.51±0.18 |

| MPTP | 0.92±0.05 | 1.09±0.09 | 1.22±0.11 | |

| Cerebellum | Saline | 0.97±0.18 | 2.81±0.12 | 3.65±0.61 |

| MPTP | 0.72±0.05 | 2.44±0.21 | 3.39±0.13 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM of monoamine concentrations (in ng/mg protein).

Dopamine utilization was calculated as [DOPAC]/[DA] and serotonin utilization was calculated as [5-HIAA]/[5-HT].

p<0.05;

p<0.001; –significantly different from saline group (N=8/group).

Discussion

Levodopa is arguably the most effective treatment for PD, but patients invariably develop motor fluctuations and dyskinesias with chronic treatment (Lang and Luzano, 1998; Obeso et al., 2000; Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Fahn, 2003; Nutt and Wooten, 2005). Treatment with direct DA agonists also causes dyskinesias, although there may be a longer interval between initiation of treatment and emergence of dyskinesias with agonists. Thus, although dopamine replacement therapy is remarkably effective in the treatment of idiopathic PD, the side effect liabilities of dopaminergic agents suggest that drugs that modulate the activity of striatal medium spiny neurons may be a useful strategy to improve motor function, perhaps with lower side effect liability. The limitations associated with dopaminergic agents prompted us to investigate the potential antiparkinsonian actions of 5-HT2 receptor antagonists.

We failed to observe a significant effect of MPTP treatment on locomotor activity, as assessed in the open field apparatus, or any significant decrement in performance in the acute rotarod task. In contrast, we observed a marked and reproducible decrease in performance on the beam traversing task. Previous examinations of the effects of MPTP treatment on locomotor activity have yielded mixed results, with some reports noting a decrease (Arai et al., 1990; Frederickson et al., 1990; Luchtman et al., 2009) and others an increase (Chia et al., 1996; Rousselet et al., 2003), but most reporting no significant change in activity (Nishi K. et al., 1991; Tomac et al., 1995; Tilllerson et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2005). Similarly, studies of performance on the acute rotarod test have yielded inconsistent results, with different studies reporting both decreases (Rozas et al., 1998; Luchtman et al., 2009) and no change in MPTP-treated mice relative to control subjects (Sedelis et al., 2000; Tillerson et al. 2002). Some of the variance across reports probably reflects technical difference in the task apparatus or testing, or differences in interval between MPTP treatment and testing or in the MPTP treatment protocol used. The latter factors have a large influence on the extent of the degree of striatal dopamine loss, and as importantly the residual striatal dopamine (Bezard and Gross, 1998).

We did observe that mice treated with MPTP were significantly impaired on the beam walking apparatus. Quinn et al. (2007) similarly reported that MPTP decreases performance in this task. In addition, impairments in beam walking that were significantly attenuated by levodopa have been reported in the aphakia (pit3x-deficient) transgenic mouse model of parkinsonism (Hwang et al., 2005).

We found that levodopa, at doses previously shown to reduce other motor deficits in animal models of parkinsonism (Fredricsson et al., 1990; Tillerson et al., 2003), reversed completely the number of footslips in the beam walking task. This finding, taken together with earlier data, suggests that performance on the beam walking test has some predictive validity for PD.

Ritanserin dose-dependently attenuated the number of footslips in the beam walking test, although at none of the doses tested was there a complete reversal of the motor deficit. The selective 5-HT2A antagonist M100907 in a dose related manner decreased the number of footslips, having a significant effect even at the lowest dose (0.1 μg/kg); however, we did not observe a complete reversal of footslips to control levels by a higher dose of M100907. In contrast to the beneficial effects of ritanserin and M100907, the 5-HT2C-preferring antagonist had no effect on performance of MPTP-treated mice in the beam walking test. These data suggest that the ability of the 5-HT2A/C antagonist ritanserin to reduce parkinsonian motor deficits is attributable to actions at the 5-HT2A but not 5-HT2C receptor.

Consistent with previous studies, MPTP treatment markedly decreased striatal DA concentrations, with a lesser but significant effect in the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens; Heikkila et al., 1984; Sundstrom et al., 1987; Stephenson et al., 2007; Nayyar et al., 2009). In contrast, we did not observe a change in striatal 5-HT concentrations. This finding is consistent with many but not all previous reports in the rodent (Hara et al., 1987; Sundstrom et al., 1987; Rozas et al., 1998; Rousselet et al., 2003; Stephenson et al., 2007; Vuckovic et al., 2008). The lack of consistent changes in nigrostriatal serotonin concentrations in the MPTP-treated mouse probably reflects the use of different MPTP treatment protocols and post-treatment survival periods (see Nayyar et al., 2009).

There have been conflicting results concerning the effects of striatal dopamine depletion on 5-HT2A receptors in the striatum. Zhang et al. (2007) noted an increase in striatal levels of the 5-HT2A transcript in response to 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesion-induced dopamine denervation. In contrast, Li et al. (2010) reported that the density of 5-HT2A receptors, as measured by assessing [3H]ketanserin binding sites, was decreased by 6-OHDA lesions of the median forebrain bundle. We are not aware of any published imaging studies of striatal 5-HT2A binding potential in idiopathic PD.

We found that ritanserin improved motor function in MPTP-treated mice. This observation is consistent with clinical data showing that ritanserin reduces bradykinesia and improves gait in PD patients (Henderson et al., 1992), as well as reduces antipsychotic drug-induced extrapyramidal side effects (Bersani et al., 1990; Miller et al., 1990, 1992). Because SB206553 failed to improve MPTP-induced motor deficits, the anti-parkinsonian action of ritanserin is probably not due to 5-HT2C receptor blockade. There are conflicting views on the role of 5-HT2C receptors in the function of the nigrostriatal DA system. Some studies indicate that 5-HT2C receptors exert tonic inhibitory control on the nigrostriatal system (De Deurwaerdere and Spampinato, 2001; De Deurwaerdere et al., 2004), whereas other reports have found no effect (Di Matteo et al., 2001).

Our results are in agreement with a recent study showing that the 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonist, ACP-103 (pimavanserin) reduced parkinsonian tremor in rats (Vanover et al., 2008). Whereas our studies have investigated the anti-parkinsonian action of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists other studies have documented the involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID). M100907 reduced dyskinesia induced by the dopamine D1 agonist SKF 82958 but not that induced by levodopa (Taylor et al., 2006). SB 206553 has been shown to enhance the antiparkinsonian effects of dopamine D1 and D2 agonists in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats with no effects on rotational behavior when administered alone (Fox and Brotchie, 2000).

The very high density of striatal 5-HT2A binding sites stands in contrast to the very low abundance of 5-HT2A mRNA in striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) (Pompeiano et al., 1994; Ward and Dorsa, 1996; Mijnster et al., 1997; Bubser et al., 2001). This is consistent with the finding that the majority of 5-HT2A receptors is localized to the terminals of corticostriatal axons (Bubser et al., 2001). The loss of striatal dopamine signaling through D2 receptors removes a tonic inhibitory constraint on cortico-striatal glutamtergic axons (DeLong, 1990; Bamford et al., 2004). Anatomical studies of the dopamine-denervated striatum have revealed an increase in the density of perforated synapses onto MSNs dendritic spines, suggestive of increased excitatory (glutamatergic) drive onto striatal projection neurons (Anglade et al., 1996; Meshul et al., 1999, 2002; Raju et al., 2008). Consistent with the anatomical studies, in vivo microdialysis studies and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy findings have suggested increased glutamate concentrations in the striatum of MPTP-treated mice (Robinson et al., 2003; Chassain et al., 2008).

Several studies suggest that normalizing increased glutamatergic drive over MSNs would be of therapeutic benefit in PD (Starr, 1995; 1998; Blandini et al., 1996; Jankovic and Hunter, 2002; Garcia et al., 2010), but clinical trials have failed, mainly because of side effects. We hypothesize that 5-HT2A heteroceptors present on corticostriatal axons dampen glutamate release and thereby may be of use in treating the motor deficits of PD. Activation of 5-HT2A heteroceptors in several brain areas has been shown to evoke glutamate release (Aghajanian and Marek, 1997; Scruggs et al., 2003).

In dopamine-depleted rats 5-HT2A receptors mediate effects associated D1 receptor function. It has been reported that treatment with D1 and 5-HT2 agonists produce synergistic induction of striatonigral gene expression (Gresch and Walker, 1999) and hyperlocomotion (Bishop and Walker, 2003). The hyperlocomotion response was suppressed by the selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 (Bishop et al., 2005). Thus it appears that in the dopamine-depleted brain, 5-HT2A receptors may regulate the direct striatal output pathway as well as the indirect glutamatergic pathway. However, because the great majority of striatal 5-HT2A receptors are localized to corticostriatal terminals (Bubser et al., 2001), a more plausible mechanism to explain our findings is an indirect action occurring through regulation of glutamate release. Future studies designed to test the relative contributions of direct vs indirect effects on MSN function will be required to define which mechanism is operative.

In conclusion, we find that 5-HT2A receptor antagonism improves motor impairments in MPTP-treated mice. This finding is consistent with earlier studies suggesting an antiparkinsonian effect of ritanserin, and specifically point to 5-HT2A receptors as providing a novel target for the treatment of parkinsonian symptoms. Further clinical exploration of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists as potential therapeutic agents in PD is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Elaine Sanders-Bush for the generous gift of M100907. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [U54 NS041071 to TAA, AYD) and the National Parkinson Foundation Center of Excellence at Vanderbilt. The content is solely the responsibility of the Authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS of the National Institutes of Health or the National Parkinson Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allbutt HN, Henderson JM. Use of the narrow beam test in the rat, 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;159:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglade P, Mouatt-Prigent A, Agid Y, Hirsch E. Synaptic plasticity in the caudate nucleus of patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5:121–128. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai N, Misugi K, Goshima Y, Misu Y. Evaluation of a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated C57 black mouse model for parkinsonism. Brain Res. 1990;515:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90576-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford NS, Zhang H, Schmitz Y, Wu NP, Cepeda C, Levine MS, Schmauss C, Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Sulzer D. Heterosynaptic dopamine neurotransmission selects sets of corticostriatal terminals. Neuron. 2004;42:653–663. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersani G, Grispini A, Marini S, Pasini A, Valducci M, Ciani N. 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin in neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism: a double-blind comparison with orphenadrine and placebo. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1990;13:500–506. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Gross CE. Compensatory mechanisms in experimental and human parkinsonism: towards a dynamic approach. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:93–116. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C, Daut GS, Walker PD. Serotonin 5-HT2A but not 5-HT2C receptor antagonism reduces hyperlocomotor activity induced in dopamine-depleted rats by striatal administration of the D1 agonist SKF 82958. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C, Walker PD. Combined intrastriatal dopamine D1 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor stimulation reveals a mechanism for hyperlocomotion in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Neuroscience. 2003;121:649–657. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandini F, Greenamyre JT, Nappi G. The role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Funct Neurol. 1996;11:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubser M, Backstrom JR, Sanders-Bush E, Roth BL, Deutch AY. Distribution of serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptors in afferents of the rat striatum. Synapse. 2001;39:297–304. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010315)39:4<297::AID-SYN1012>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassain C, Bielicki G, Durand E, Lolignier S, Essafi F, Traore A, Durif F. Metabolic changes detected by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo and in vitro in a murin model of Parkinson's disease, the MPTP-intoxicated mouse. J Neurochem. 2008;105:874–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia LG, Ni DR, Cheng LJ, Kuo JS, Cheng FC, Dryhurst G. Effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine on the locomotor activity and striatal amines in C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci Lett. 1996;218:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)13091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deurwaerdere P, Navailles S, Berg KA, Clarke WP, Spampinato U. Constitutive activity of the serotonin2C receptor inhibits in vivo dopamine release in the rat striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3235–3241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0112-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deurwaerdere P, Spampinato U. The nigrostriatal dopamine system: a neglected target for 5-HT2C receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:502–504. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90110-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, Cameron DS. Pharmacological characterization of dopamine systems in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 1992;46:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90007-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, Tam SY, Roth RH. Footshock and conditioned stress increase 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) in the ventral tegmental area but not substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1985;333:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo V, De Blasi A, Di Giulio C, Esposito E. Role of 5-HT(2C) receptors in the control of central dopamine function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Gao X, Story GM, Anderson LI, Kucera J, Walro JM. Evaluation of nigrostriatal dopaminergic function in adult +/+ and +/- BDNF mutant mice. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:121–128. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S. Description of Parkinson's disease as a clinical syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;991:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Diguet E, Bioulac B, Tison F. MPTP potentiates 3-nitropropionic acid-induced striatal damage in mice: reference to striatonigral degeneration. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SH, Brotchie JM. 5-HT(2C) receptor antagonists enhance the behavioural response to dopamine D(1) receptor agonists in the 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson A, Plaznik A, Sundstrom E, Jonsson G, Archer T. MPTP-induced hypoactivity in mice: reversal by L-dopa. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;67:295–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia BG, Neely MD, Deutch AY. Cortical regulation of striatal medium spiny neuron dendritic remodeling in parkinsonism: modulation of glutamate release reverses dopamine depletion-induced dendritic spine loss. Cereb Cortex. 2010 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp317. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 20118184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresch PJ, Walker PD. Synergistic interaction between serotonin-2 receptor and dopamine D1 receptor stimulation on striatal preprotachykinin mRNA expression in the 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;70:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Tohyama I, Kimura H, Fukuda H, Nakamura S, Kameyama M. Reversible serotoninergic neurotoxicity of N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in mouse striatum studied by neurochemical and immunohistochemical approaches. Brain Res. 1987;410:371–374. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila RE, Hess A, Duvoisin RC. Dopaminergic neurotoxicity of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine in mice. Science. 1984;224:1451–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.6610213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J, Yiannikas C, Graham JS. Effect of ritanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, on Parkinson's disease. Clin Exp Neurol. 1992;29:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DY, Fleming SM, Ardayfio P, Moran-Gates T, Kim H, Tarazi FI, Chesselet MF, Kim KS. 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine reverses the motor deficits in Pitx3-deficient aphakia mice: behavioral characterization of a novel genetic model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2132–2137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3718-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J, Hunter C. A double-blind, placebo-controlled and longitudinal study of riluzole in early Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehne JH, Baron BM, Carr AA, Chaney SF, Elands J, Feldman DJ, Frank RA, van Giersbergen PL, McCloskey TC, Johnson MP, McCarty DR, Poirot M, Senyah Y, Siegel BW, Widmaier C. Preclinical characterization of the potential of the putative atypical antipsychotic MDL 100,907 as a potent 5-HT2A antagonist with a favorable CNS safety profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:968–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1044–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie RA, Moorman JM, Coulson A, Grahame-Smith DG. Serotonin2/1C receptor activation causes a localized expression of the immediate-early gene c-fos in rat brain: evidence for involvement of dorsal raphe nucleus projection fibres. Neuroscience. 1993;53:457–463. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huang XF, Deng C, Meyer B, Wu A, Yu Y, Ying W, Yang GY, Yenari MA, Wang Q. Alterations in 5-HT2A receptor binding in various brain regions among 6-hydroxydopamine-induced parkinsonian rats. Synapse. 2010;64:224–230. doi: 10.1002/syn.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas G, Bonhomme N, De Deurwaerdere P, Le Moal M, Spampinato U. 8-OH-DPAT, a 5-HT1A agonist and ritanserin, a 5-HT2A/C antagonist, reverse haloperidol-induced catalepsy in rats independently of striatal dopamine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;131:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s002130050265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchtman DW, Shao D, Song C. Behavior, neurotransmitters and inflammation in three regimens of the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshul CK, Emre N, Nakamura CM, Allen C, Donohue MK, Buckman JF. Time-dependent changes in striatal glutamate synapses following a 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. Neuroscience. 1999;88:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshul CK, Kamel D, Moore C, Kay TS, Krentz L. Nicotine alters striatal glutamate function and decreases the apomorphine-induced contralateral rotations in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:257–274. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijnster MJ, Raimundo AG, Koskuba K, Klop H, Docter GJ, Groenewegen HJ, Voorn P. Regional and cellular distribution of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine2a receptor mRNA in the nucleus accumbens, olfactory tubercle, and caudate putamen of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CH, Fleischhacker WW, Ehrmann H, Kane JM. Treatment of neuroleptic induced akathisia with the 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CH, Hummer M, Pycha R, Fleischhacker WW. The effect of ritanserin on treatment-resistant neuroleptic induced akathisia: case reports. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(92)90076-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A, Ohashi S, Nakai M, Moriizumi T, Mitsumoto Y. Neural mechanisms underlying motor dysfunction as detected by the tail suspension test in MPTP-treated C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci Res. 2005;51:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar T, Bubser M, Ferguson MC, Diana Neely M, Shawn Goodwin J, Montine TJ, Deutch AY, Ansah TA. Cortical serotonin and norepinephrine denervation in parkinsonism: preferential loss of the beaded serotonin innervation. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi K, Kondo T, Narabayashi H. Destruction of norepinephrine terminals in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated mice reduces locomotor activity induced by L-dopa. Neurosci Lett. 1991;123:244–247. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90941-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt JG, Wooten GF. Diagnosis and initial management of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1021–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp043908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Olanow CW, Nutt JG. Levodopa motor complications in Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:S2–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano M, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor family mRNAs: comparison between 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;23:163–178. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S, Jackson-Lewis V, Naini AB, Jakowec M, Petzinger G, Miller R, Akram M. The parkinsonian toxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): a technical review of its utility and safety. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn LP, Perren MJ, Brackenborough KT, Woodhams PL, Vidgeon-Hart M, Chapman H, Pangalos MN, Upton N, Virley DJ. A beam-walking apparatus to assess behavioural impairments in MPTP-treated mice: pharmacological validation with R-(-)-deprenyl. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;164:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju DV, Ahern TH, Shah DJ, Wright TM, Standaert DG, Hall RA, Smith Y. Differential synaptic plasticity of the corticostriatal and thalamostriatal systems in an MPTP-treated monkey model of parkinsonism. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1647–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Freeman P, Moore C, Touchon JC, Krentz L, Meshul CK. Acute and subchronic MPTP administration differentially affects striatal glutamate synaptic function. Exp Neurol. 2003;180:74–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselet E, Joubert C, Callebert J, Parain K, Tremblay L, Orieux G, Launay JM, Cohen-Salmon C, Hirsch EC. Behavioral changes are not directly related to striatal monoamine levels, number of nigral neurons, or dose of parkinsonian toxin MPTP in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:218–228. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas G, Liste I, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Sprouting of the serotonergic afferents into striatum after selective lesion of the dopaminergic system by MPTP in adult mice. Neurosci Lett. 1998;245:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs JL, Patel S, Bubser M, Deutch AY. DOI-Induced activation of the cortex: dependence on 5-HT2A heteroceptors on thalamocortical glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8846–8852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08846.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs JL, Schmidt D, Deutch AY. The hallucinogen 1-[2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl]-2-aminopropane (DOI) increases cortical extracellular glutamate levels in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;346:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelis M, Schwarting RK, Huston JP. Behavioral phenotyping of the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr MS. Antiparkinsonian actions of glutamate antagonists--alone and with L-DOPA: a review of evidence and suggestions for possible mechanisms. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1995;10:141–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02251229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr MS. Antagonists of glutamate in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: from laboratory to the clinic. Amino Acids. 1998;14:41–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01345240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Ramirez A, Long J, Barrezueta N, Hajos-Korcsok E, Matherne C, Gallagher D, Ryan A, Ochoa R, Menniti F, Yan J. Quantification of MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the mouse substantia nigra by laser capture microdissection. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;159:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome EM, Cepeda IL, Sossi V, Doudet DJ. Evaluation of the integrity of the dopamine system in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease: small animal positron emission tomography compared to behavioral assessment and autoradiography. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:292–299. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom E, Stromberg I, Tsutsumi T, Olson L, Jonsson G. Studies on the effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) on central catecholamine neurons in C57BL/6 mice. Comparison with three other strains of mice. Brain Res. 1987;405:26–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Bishop C, Ullrich T, Rice KC, Walker PD. Serotonin 2A receptor antagonist treatment reduces dopamine D1 receptor-mediated rotational behavior but not L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements in the unilateral dopamine-depleted rat. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Caudle WM, Reveron ME, Miller GW. Detection of behavioral impairments correlated to neurochemical deficits in mice treated with moderate doses of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:80–90. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Miller GW. Grid performance test to measure behavioral impairment in the MPTP-treated-mouse model of parkinsonism. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123:189–200. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomac A, Lindqvist E, Lin LF, Ogren SO, Young D, Hoffer BJ, Olson L. Protection and repair of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system by GDNF in vivo. Nature. 1995;373:335–339. doi: 10.1038/373335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urakawa S, Hida H, Masuda T, Misumi S, Kim TS, Nishino H. Environmental enrichment brings a beneficial effect on beam walking and enhances the migration of doublecortin-positive cells following striatal lesions in rats. Neuroscience. 2007;144:920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanover KE, Betz AJ, Weber SM, Bibbiani F, Kielaite A, Weiner DM, Davis RE, Chase TN, Salamone JD. A 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonist, ACP-103, reduces tremor in a rat model and levodopa-induced dyskinesias in a monkey model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovic MG, Wood RI, Holschneider DP, Abernathy A, Togasaki DM, Smith A, Petzinger GM, Jakowec MW. Memory, mood, dopamine, and serotonin in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse model of basal ganglia injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RP, Dorsa DM. Colocalization of serotonin receptor subtypes 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT6 with neuropeptides in rat striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1996;370:405–414. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960701)370:3<405::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Andren PE, Svenningsson P. Changes in 5-HT2 receptor mRNAs in striatum and subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson's disease model. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]