Abstract

Objective

To implement and assess a Web-based patient care portfolio system for development of pharmaceutical care plans by students completing advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) throughout a statewide preceptor network.

Design

Using a Web database, students in APPEs documented 6 patient cases within 5 disease state categories. Through discussion of the disease states and inclusion of patient information such as problems, desired outcomes, and interventions, a complete pharmaceutical care plan was developed for each patient.

Assessment

Student interventions were compared by geographical regions to assess continuity of patient care activities by students. Additionally, students completed an evaluation of the portfolio course to provide feedback on the portfolio process. Students documented an average of 1.8 therapeutic interventions per patient case and documented interventions in all geographical regions. The majority of students indicated that the portfolio process improved their ability to develop a pharmaceutical care plan.

Conclusion

The Web-based patient care portfolio process assisted with documentation of compliance with Accreditation Council of Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards and College of Pharmacy Competency Statements. Students indicated the portfolio process was beneficial in developing skills needed for creating pharmaceutical care plans.

Keywords: portfolio, pharmaceutical care, advanced pharmacy practice experience, Web, experiential education

INTRODUCTION

Doctor of pharmacy (Pharm D) students completing APPEs at the University of Georgia (UGA) College of Pharmacy are exposed to a wide variety of practice models. The assistant dean for experience programs, with the help of 4 regional faculty members known as regional coordinators, developed an experiential education program which includes approximately 600 preceptors in over 300 practice settings throughout the state. These practice sites are diverse and include large multifacility health systems and community pharmacies operated by national chains, as well as small rural hospitals and independent pharmacies. A program was designed to assure that all PharmD students, regardless of experience site, develop comparable abilities to design, document, and implement plans for patient-centered pharmaceutical care.

In 2004, the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) described the provision of pharmaceutical care in its Educational Outcomes, including patient-centered care and designing pharmaceutical care plans.1 Today the ACPE, in its Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, directs that colleges and schools of pharmacy shall have a system of evaluation of curricular effectiveness, which includes student portfolios to document achievement of competencies throughout the curriculum and practice experiences.2 To assure quality experiences for our students, to allow demonstration of the provision of pharmaceutical care, and to meet established educational outcomes, a Web-based patient care portfolio was developed.

The online course entitled, Pharmacotherapy Care Plans and Professional Development, was first added into the curriculum for students on APPEs in the fall semester of 2005. Goals for students, specific to the care plan portion of this course, included demonstrating an understanding of the pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of common acute and chronic disease states, and integrating therapeutic knowledge into pharmaceutical care plans.

Sparse information has been published on the use of patient care portfolios. In 2005, Ragan published a description of a Web-based tool to assist in managing distance-based APPEs by faculty members who were geographically distant from the student and the APPE site.3 This instrument was described as a component of a distance-based, nontraditional doctor of pharmacy program. Kassam discussed the use of learning portfolios to record direct and non-direct pharmaceutical care by students, and also as an assessment tool to determine students' clinical reasoning and pharmaceutical care skills.4 Other portfolios described include those for competency assessment,5 experiential practice portfolios to document instruction and learning,6 and also reflective portfolios.7 This paper describes the experience of the UGA College of Pharmacy with a Web-based patient care portfolio approach to developing and documenting patient-centered pharmaceutical care plans during APPEs.

DESIGN

The UGA College of Pharmacy used an online experiential education database system to assist with organizing the enormous amount of data required by the Office of Experience Programs. The experiential education database sorted and stored information on students, preceptors, and APPEs. Therefore, this information was readily available to students, faculty members, and preceptors via the Internet through use of password-protected access. Within this database, a patient care portfolio system was developed to guide students performing APPEs through the processes of collecting and documenting patient and disease state information, analyzing this data, developing a plan for medication therapy, and implementing that plan. Because all student entries were submitted into the experiential education database and stored electronically, data from individual cases could be extracted easily to make assessments and comparisons of students' interventions and activities at various practice sites throughout the state.

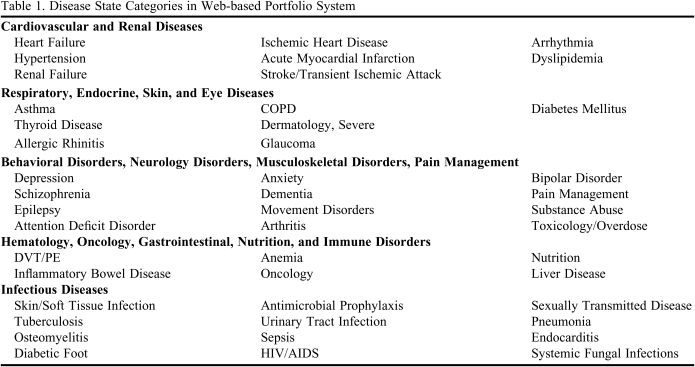

To allow flexibility and still assure exposure to a variety of commonly occurring disease states, students were required to include a minimum of 6 patient cases in their portfolio during the APPEs. Acceptable disease states were divided into 5 categories, and students were required to choose a minimum of 1 from each group. The only disease state that was mandatory was substance abuse (Table 1).

Table 1.

Disease State Categories in Web-based Portfolio System

Abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT/PE = deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

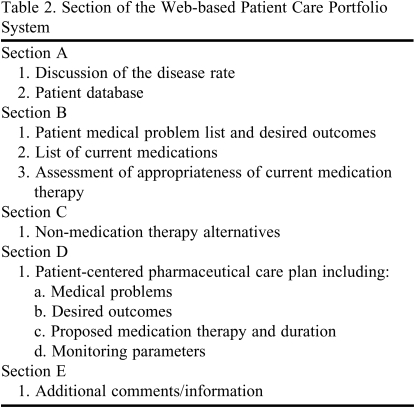

Once the disease state to be managed was selected, the student was granted access to the patient care portfolio form. This form was divided into 5 distinct sections (Table 2) designed to guide the student through a logical step-by-step process for providing patient-centered pharmaceutical care.

Table 2.

Section of the Web-based Patient Care Portfolio System

To demonstrate knowledge of the pathophysiology of the selected disease, students began the portfolio with a discussion of the disease state, emphasizing the definition of the disease, causes or risk factors, typical symptoms, and typical treatment. Students were required to document any reference material or guidelines used to develop this section. The patient database included patient demographic data, chief complaint, history of the illness, past medical history, relevant vital signs, and medication allergies (if any), including the type of reaction and relevant laboratory data. Compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines was stressed and strictly enforced.

The problem list was intended to be developed in conjunction with the patient, preceptor, and other health care personnel, allowing for an interdisciplinary approach. Desired outcomes were to be supported by consensus guidelines when such guidelines were available. After completing the list of current medications, students had to consider the appropriateness of each item relative to medical conditions, indication, duplication, dosing, reactions, side effects, and interactions. When medication problems were noted, students indicated their recommendation for management of the problem. Additionally, students documented non-medication alternatives which would help achieve the desired outcomes.

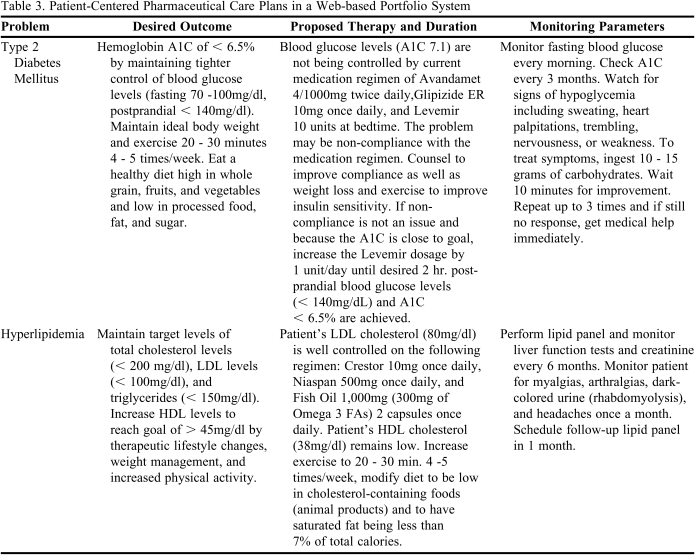

In the patient-centered pharmaceutical care plan, students documented the proposed pharmaceutical therapies. Also included in this section were monitoring parameters for the proposed medication regimen. Students were expected to include monitoring for efficacy as well as safety. (Refer to Table 3 for an example of the patient-centered pharmaceutical care plan as it appeared in the Web-based patient care portfolio.) To foster interdisciplinary care, students were directed to identify individuals to whom the plan should be communicated, including physicians, pharmacists, nurses, the patient and/or family member, or other caregiver.

Table 3.

Patient-Centered Pharmaceutical Care Plans in a Web-based Portfolio System

After electronic submission, 1 of 5 faculty reviewers from the experiential department opened the experiential education database to examine the work and provided feedback on appropriateness and completeness. For the APPEs, students were randomly assigned to 1 of 9 geographical regions of the state. Student submissions were reviewed by the regional coordinator for the area to which the student was assigned. On average, each regional coordinator reviewed submissions from approximately 24 students.

The Web-based system allowed ongoing electronic dialogue between student and reviewer. If significant improvements were needed, the plan was revised by the student. As students progressed through the year, therapies may have been challenged to ascertain the level of student confidence and ability to defend recommendations.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

The assessment process for the Web-based patient care portfolio was 2-fold. First, student interventions were compared to assess continuity of patient-care activities across the state. Second, students were surveyed to gain feedback on the portfolio process. Institutional review board approval was obtained for gathering this de-identified data.

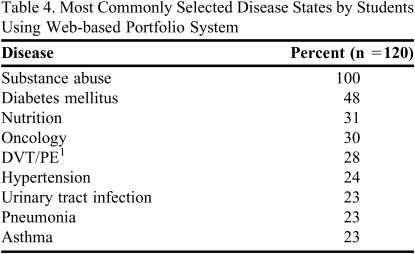

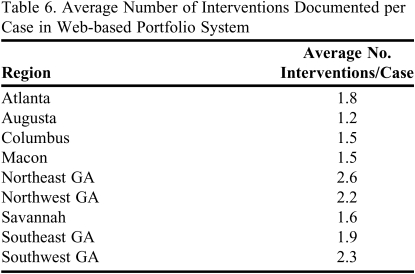

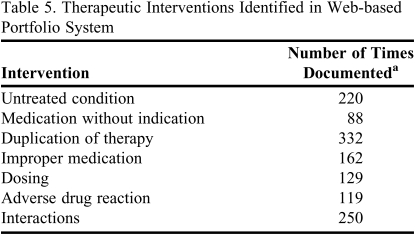

Information comparing student portfolios is summarized in Tables 4 through 6. Table 4 depicts the disease state options selected most often by students. Besides substance abuse, which was a required case, 48% of the students selected a case in diabetes mellitus to include in their portfolio. Several of the most frequently selected disease states are represented in the core disease states of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Professional Affairs Committee.8 These include diabetes mellitus, oncology, hypertension, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia. Many patient care portfolios documented therapeutic interventions (Table 5). In 721 cases, students documented therapeutic duplicates most often (332 times), followed by interactions (250 times). Students documented an average of 1.8 therapeutic interventions per patient case, with interventions documented in all geographical regions across the state (Table 6). Evidence of these interventions documents the ability of rural as well as metropolitan practice sites to offer opportunities for students to provide direct patient care. Approximately 48% of the submitted cases were completed during acute medicine APPEs.

Table 4.

Most Commonly Selected Disease States by Students Using Web-based Portfolio System

Abbreviations: DVT/PE = deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

Table 6.

Average Number of Interventions Documented per Case in Web-based Portfolio System

Table 5.

Therapeutic Interventions Identified in Web-based Portfolio System

a Within the 721 total patient cases, the same type of intervention may have been documented more than once in a particular case

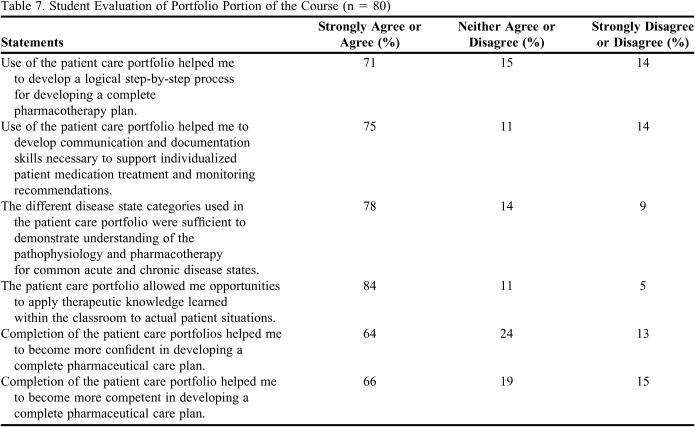

An evaluation of the portfolio course was completed by students at the end of the APPEs (Table 7). Of 120 students, 80 evaluations were completed for a return rate of 67%. Most of the students who responded (71%) either agreed or strongly agreed that the portfolio process helped them develop a logical process for creating a pharmaceutical care plan. Students also felt (75%) that the process helped foster their communication and documentation skills. Confidence and competence in developing a pharmaceutical care plan were reported improved by 64% and 66% of respondents, respectively. All the experiential faculty reviewers noted continuous improvements as students gained experience with the portfolio expectations.

Table 7.

Student Evaluation of Portfolio Portion of the Course (n = 80)

One area of student improvement was in the discussion of the disease state. In this section students demonstrated their competence with the pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of the selected disease. Faculty reviewers encouraged students to emphasize the definition of the disease, its causes or risk factors, typical symptoms, and accepted treatments. Omissions of one or more of these components required the student to revise and resubmit the case. As students progressed through the course, reviewers noted significant improvement in the students' ability to adequately describe each of these areas.

Faculty reviewers also noted improvements in the students' ability to apply therapeutic knowledge learned in the didactic portion of the curriculum to their pharmaceutical care plans. In the classroom, students were introduced to evidence-based guidelines. Faculty reviewers of the patient care portfolios looked for adherence to guidelines in the pharmaceutical care plans of submitted portfolios (where guidelines existed). If existing guidelines were not followed, the student was expected to provide documentation to support the variation. Furthermore, medication problems noted by the student had to be addressed in the pharmaceutical care plan through methods such as alternative therapy, dose modification, or additional monitoring. Reviewers reported substantial improvements in the students' ability to make reasonable recommendations to address medication problems and suggest appropriate monitoring of medication therapy in their pharmaceutical care plans.

DISCUSSION

A major goal of APPEs is to allow pharmacy students to transition from didactic learning and apply their knowledge in actual patient care. This transition is accomplished frequently at remote practice sites under the supervision of volunteer preceptors. At the University of Georgia College of Pharmacy, approximately 10% of the APPEs have been directly precepted by faculty members, while 90% have been precepted by practicing pharmacists who are not employees of the college. As a result, it has been difficult for the parent institution to assure continuity and document excellence in experiential education. In fact, pharmacy staff workload and the shortage of pharmacists have been documented as impacting experiential preceptors.8, 9 Through the use of a Web-based patient care portfolio system, students demonstrated pharmaceutical care skills under the guidance of pharmacy practitioners. These activities were documented and transmitted to experiential faculty using our experiential education database to provide student/faculty interaction and ongoing monitoring of student progress by faculty members, and to stimulate active learning.

The Web-based patient care portfolio process was designed to foster self-directed learning. Students were free to select the listed disease states they wanted to focus on, collect the patient data they felt was necessary to provide appropriate care, design the plan of care, and decide to whom it should be communicated. Additionally, students were allowed to choose the reference materials they felt were best suited to the needs of their particular patients.

Through this process students should be able to develop a system to synthesize their own pharmaceutical care plans upon entering practice. Students should be more confident and competent in designing and monitoring pharmaceutical care plans. The Web-based patient care portfolio allowed students to demonstrate their understanding of the pathophysiology and pharmacology of commonly occurring disease states. Additionally, students were able to apply their therapeutic knowledge to actual patient situations. Of note, regional coordinators reported that a steep learning curve existed for the first 2 or 3 submissions as students perfected their work early in the APPE sequence. After these initial portfolio submissions, the students' cases improved as they gained and integrated knowledge and assessment skills.

A limitation may exist related to our assessment process. Although most students agreed that the portfolios were helpful in the learning process, no assessment was completed prior to the course. In addition, data were not captured that showed improvement in case quality as the year progressed. Another limitation of the patient care portfolio process was the time commitment required to evaluate properly the submitted patient cases. Initially, experiential faculty members wanted students to submit 10 patient care cases during the APPEs. However, this number was reduced to 6 due to the time needed to review submissions. In many instances, review of a case required about 20 minutes, but for complex patients, thorough review took up to an hour. Faculty reviewers were sometimes at a disadvantage if a patient case dealt with a particular disease state or patient population with which they had limited experience. Also, as the deadline for students to submit cases approached near the end of each experience, faculty reviewers may have received numerous cases to evaluate at one time.

An additional concern with the patient care portfolio process was that faculty reviewers were not able to discern if the interventions documented by students were actually implemented or if they were only suggested interventions. To capture this information, an additional field may be required on the portfolio Web page to allow students to document whether a recommendation was accepted or rejected by the medical team.

Occasionally, students felt limited if they wanted to develop a patient care case for a disease state not listed in the experiential database. The disease states from which students chose were selected because the pharmacy curriculum included lectures covering each of them. This list represented the core disease states listed by the AACP Professional Affairs Committee and was designed to cover illnesses which would be encountered by pharmacy generalists, as opposed to illnesses which might be seen only in specialty practice settings.10 Substance abuse was listed as a required submission to help students meet the College of Pharmacy's Competency Statement Number 8, which includes identifying individuals who are abusing medications and recommending medications for chemical dependency.11

SUMMARY

The University of Georgia used a Web-based patient care portfolio system allowing APPE students to document patient care activities throughout the state, which proved to be beneficial to both students and faculty members. Student feedback from the course was positive, with the majority of the students either agreeing or strongly agreeing that the patient care portfolio process was beneficial in developing pharmaceutical care plans for patients. The 5 experience program faculty members also benefitted from the portfolio system and were able to guide student progress in developing pharmaceutical care plans. In addition, the faculty members were able to see the types of patients students encountered and the types of interventions students recommended.

REFERENCES

- 1. The AACP Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Advisory Panel on Educational Outcomes. 2004 Educational Outcomes. http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/Resources/6075_CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2010.

- 2. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree Adopted January 15, 2006. http://www.acpe-accredit.org./standards. Accessed March 31, 2010.

- 3.Ragan RE, Dahm SN. Development of an internet-based management tool for advanced practice experience distance education students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3) Article 47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassam R. Evaluation of pharmaceutical care opportunities within an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3) doi: 10.5688/aj700349. Article 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannefer EF, Henson LC. The portfolio approach to competency-based assessment at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):493–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ead30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolte SK, Scheer SB, Robinson ET. The reliability of non-cognitive admission measures in predicting non-traditional doctor of pharmacy student performance outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1) Article 18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plaza CM, Draugalis JR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710234. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skrabal MZ, Jones RM, Nemire RE. National Survey of Volunteer Pharmacy Preceptors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205112. Article 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bracket PD, Byrd DC, Duke LJ, Fetterman JW. Barriers to expanding advanced pharmacy practice experience site availability in an experiential education consortium. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(5) doi: 10.5688/aj730582. Article 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Littlefield LC, Haines ST, Harralson AF. Academic pharmacy's role in advancing practice and assuring quality in experiential education: report of the 2003-2004 professional affairs committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article S8. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Competency Statements, Terminal Objectives, and Enabling Objectives for the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. The University of Georgia College of Pharmacy. Internal Publication, Revised 2003.