Abstract

Objective

To explore pharmacy students' experiences with and perceptions of aggressive incidents in pharmacy practice.

Methods

Data were taken from a survey completed by second-year pharmacy (P2) students and analyzed using a retrospective, cross-sectional design. Survey items were adapted using the following scales: Perception of Aggression Survey (POAS), List of Aggressive Incidents experienced by mental health staff, and List of Emotions experienced by nurses.

Results

The majority of respondents did not identify aggression as normal, instead perceiving it as a violent reaction and functional. The 3 most frequent aggressive incidents experienced were: verbal abuse to face (40%); verbal abuse on the phone (39%); and refusal to cooperate with instructions (34%). The 3 most frequent emotions reported were: frustration (70%), empathy (65%), and no pride in their profession (70% rarely-never).

Conclusion

Pharmacy students reported experiencing aggressive incidents with patients in person and on the phone, and with patients not following instructions. Preparing future pharmacists in techniques to address and resolve patients' aggression must become a priority for pharmacy academia and further research in this area is needed.

Keywords: aggression, aggressive incidents, emotions

INTRODUCTION

As pharmacy practice continues to evolve and emphasize pharmaceutical care, pharmacists face many new challenges. A diverse patient population, increased demands on pharmacists' time, and more interactions with patients and other healthcare providers all will impact pharmacists' practice behaviors. An individual's level of frustration increases as the number of stressors in a situation increases, and as frustration levels increase, so too does the likelihood of emotional reactions such as aggressive behavior.1-3 Although reducing stressors minimizes the likelihood of aggressive behavior occurring, to do so, aggressive actions and anger must be recognized and a manner of communication that respects the other person's emotions, while managing one's own feelings, must be adopted. Thus, if pharmacists are to provide quality patient care without increasing their own frustration and emotional levels, or that of their patients, they need to be able to identify and manage patients' emotional states as well as their own.4,5

Aggression has been well studied in several professions.6-8 The field of psychology describes aggression as any behavior intended to harm a target person where the target person is motivated to avoid the harmful action.9 So if someone is harmed by an unintentional act, it would not be considered aggressive because the person who caused it did not intend it and the person affected was not motivated to avoid it. Ethologists consider the biological factors of aggression, whereas psychologists and other health care professionals consider nature-nurture factors. Healthcare professionals consider hostile behaviors that occur in the course of their practice as aggression.10 A consistent finding across the literature is the difficulty in defining aggression, and how it is perceived depends on the context in which it is applied and the theory that explains it.6,11 In this study, the healthcare professional view and definition of aggression were utilized.

Pharmacists' ability to handle emotionally tense situations has received little attention in the pharmacy research literature. Didactically, pharmacy students are taught to be sensitive to patients' emotional and psychological states in the delivery of patient-centered care and to demonstrate empathy and cultural competence in the process. Students are taught that empathy is the cornerstone of building the therapeutic alliance4 and improves patient adherence.5 Attention is given to the professional and ethical responsibility that directs them to show tolerance and work toward developing therapeutic relationships that improve treatment outcomes. For example, pharmacy students are taught how to effectively work with angry patients by being assertive yet empathic so that treatment outcomes can be optimized.

Interestingly, while students are taught how to manage angry patients, little is known about how students perceive patients' aggression and their experiences with and emotions surrounding aggressive incidents with patients. It is important to understand students' perceptions of aggression, their past experiences with aggressive incidents, and their emotional state during aggressive incidents as these can influence their behavior during future interactions with patients and affect treatment outcomes.

The main objective of this study conducted at the Arnold and Marie Schwartz College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (AMSCPHS), Long Island University, was to describe pharmacy students' perceptions of and experiences with aggression in pharmacy practice and to understand their emotions during aggressive incidents. A secondary objective of this study was to identify a future agenda for research on aggression in pharmacy practice.

METHODS

A retrospective, cross-sectional design was used to analyze survey data gathered from a convenience sample of 87 P2 students enrolled in PH 200, a course on communication skills in pharmacy practice. The survey instrument was completed by students through WebCT (Blackboard, Washington, DC), an online course management system, the first week of the semester before the instructor taught communication skills required in different encounters, such as dealing with difficult or aggressive patients and working in interprofessional health care teams, and before students started IPPE assignments. Before completing the survey instrument, students were asked to give voluntary consent for the data gathered to be used for research purposes, and they received grade points for completing the assessment regardless of whether they gave consent. Only data from students who gave consent were used for analysis in this study. The consent procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Long Island University.

Data analyzed for this study pertained to the survey component of the “Dealing with Difficult Patients” class assignment. The survey instrument for the assignment was developed by adapting 3 scales identified from the health professions aggression literature: (1) the perception of aggression scale,12 (2) a list of aggressive incidents experienced by community mental health staff,13 and (3) the list of emotions experienced by nurses after an aggressive incident.14 The perception of aggression scale (POAS) is a reliable and valid 29-item scale to assess how nurses perceive patient aggression and uses a 5-point Likert scale of 1= strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.12 The POAS is composed of 3 domains: aggression as normal behavior, aggression as a violent behavior, and aggression as a functional behavior. In adapting the scale, the term “nurses” was replaced with “pharmacists.” The list of aggressive incidents experienced by community mental health staff members is a comprehensive list of aggressive incidents including verbal and physical abuse, threatening and disruptive behaviors, and sexual assault.13 The list of emotions experienced by nurses14 is a comprehensive list of common and uncommon reactions to aggression, such as anger, fear, helplessness, etc. Both the aggressive incidents list and the emotions experienced list were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale on which 1 = always and 5 = never. Each scale was adapted to fit pharmacy practice-related aggressive incidents and challenges and was face-validated by faculty members in the Social Administrative Sciences Division at the college prior to its inclusion in the final draft of the survey instrument. In addition to these items, demographic data such as student age, ethnicity, and work experience were also collected.

Student responses were exported from WebCT into SPSS, version 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Only data from students who gave consent to use the data for research purposes were exported. Descriptive statistics including frequency and cross-tabulations are presented.

RESULTS

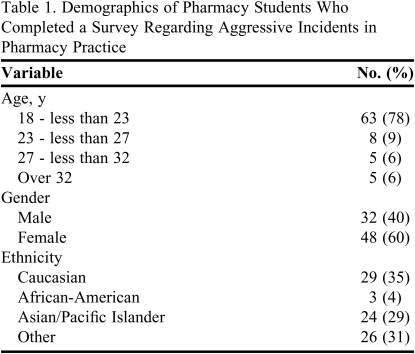

Data from 83 (94%) consenting students were analyzed for the study. Items for which students did not provide a response were treated as missing data. Over two-thirds of respondents were between 18 and 23 years of age and approximately 60% were female (Table 1). Respondents represented diverse ethnicities: white (35%), African American (4%), Asian/Pacific Islander (29%), and other (31%). Reliability of each of the scales was measured using Cronbach's alpha. For items within the 3 domains of the POAS scale, the reliability coefficients were 0.90 for items in the normal domain, 0.87 for items in the violent domain, and 0.64 for items in the functional domain. Even though the reliability of the items in the functional domain was moderate, the reliability coefficient for the complete POAS scale was 0.84, indicating the overall reliability of the scale was high. The reliability coefficient for the list of aggressive incidents, was 0.89, and the reliability coefficient for the list of emotional responses to aggressive incidents was 0.91, indicating that both lists had high reliability.

Table 1.

Demographics of Pharmacy Students Who Completed a Survey Regarding Aggressive Incidents in Pharmacy Practice

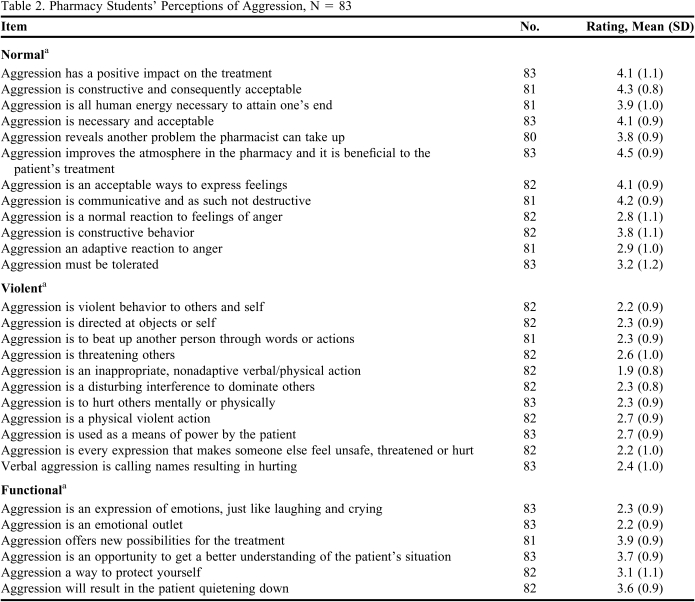

Pharmacy students mean scores on the majority of items in the normal domain were over 4, indicating they did not see aggression as a normal reaction (Table 2). Their mean scores on items in the violent domain were close to 2, indicating they saw often-viewed aggression as a violent reaction. Also, their mean scores on the items in the functional domain were in the 3 - 3.5 range, indicating they sometimes viewed aggression as having a function. No significant differences were found when students' scores on items on the 3 domains of aggression were compared across age, gender, and ethnicity (Table 3).

Table 2.

Pharmacy Students' Perceptions of Aggression, N = 83

a Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree

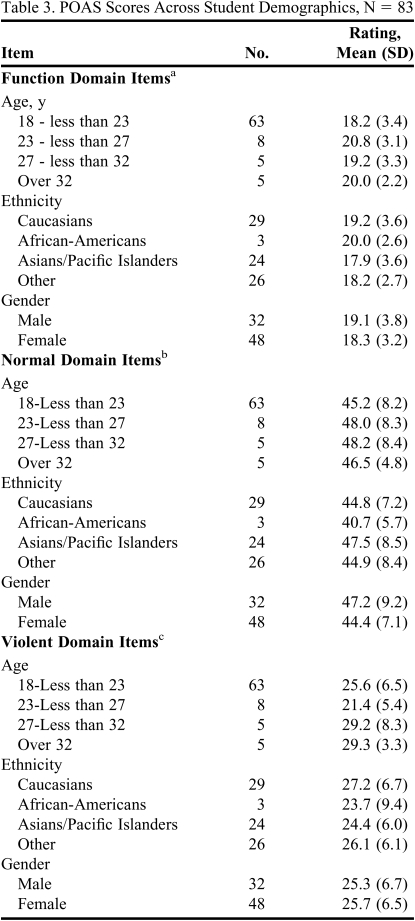

Table 3.

POAS Scores Across Student Demographics, N = 83

a Possible score range: 6-30

b Possible score range: 12-60

c Possible score range: 11-55

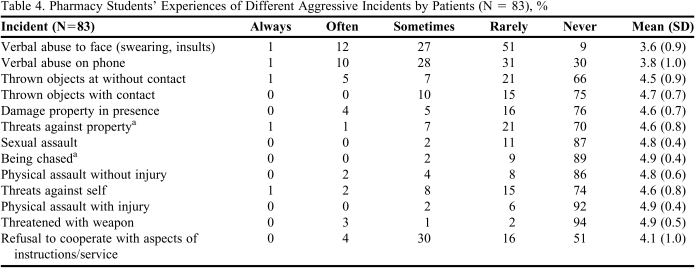

Pharmacy students reported having experienced several aggressive incidents (Table 4) with the 3 most frequent being verbal abuse to face (40%); verbal abuse on the phone (39%); and refusal to cooperate with instructions (34%).

Table 4.

Pharmacy Students' Experiences of Different Aggressive Incidents by Patients (N = 83), %

a n=82

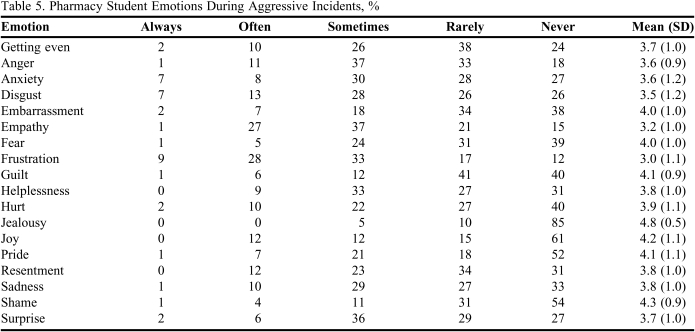

Pharmacy students reported having experienced various emotions after experiencing an aggressive incident (Table 5), with the 3 most frequent (always/often/sometimes) being frustration (70%); empathy (65%); and no pride (70% rarely-never).

Table 5.

Pharmacy Student Emotions During Aggressive Incidents, %

Note: Not all participants responded to all items; N value ranged from 81 to 83

DISCUSSION

In most health profession training programs where direct patient contact is required, students are trained to observe patients' emotions, in particular anger, and taught strategies to cope with angry feelings. Instructors in social work and psychology use patients' anger to understand their experiences and to help them heal15 and address how to manage anger as part of students' training. However, in pharmacy education, educators still ignore the role anger plays in patient care, overcoming barriers to treatment goals and pharmacists' safety. While courses in communication skills suggest ways for students to manage angry patients,4 students also must learn to recognize the role their perceptions and reactions to aggressive incidents plays in their practice.

The demands of patient-centered care will undoubtedly introduce additional stressors to an already stressful work environment. How students handle patient-related stressors is influenced by their perceptions, past experiences, and emotion management skills. This is the first study to explore the perception of aggression in pharmacy practice. In this study, students perceived aggression as a violent reaction that may serve a purpose. This is different from findings of earlier studies12 where nurses perceived aggression to be a normal reaction to anger. As Jansen explained, aggression for nurses is a “multi-dimensional phenomenon.” Nurses witness patients' anger in a number of different situations and may come to expect aggression as a natural response to patients' disability and more easily observable frustrations. For pharmacists, however, anger may be perceived as less multi-dimensional because it usually is observed in a more restricted context as pharmacists' exposure to patients is often brief and unscheduled. Also, seasoned nurses may normalize aggressive incidents over time, whereas 18- to 23- year-old pharmacy students may be more responsive to aggressive incidents. Professionals who see aggression as a normal reaction are more likely to under report aggressive behaviors and less likely to intervene. 12 Normalizing aggression can result from professionals perceiving it as part of the job experience,13 and being unaware can impact personal health and how patients are treated. Pharmacy education, therefore, must consider the uniqueness of how aggressive incidents occur in pharmacy settings and provide students with skills to identify and mitigate, if not use, them in patient encounters.

Participants in the study worked at pharmacies where interactions with patients were direct and personal and either face-to-face or on the phone. Pharmacy students identified verbal abuse to face, verbal abuse on the phone, and refusal to cooperate as the 3 most common aggressive incidents they experienced. When patients are distressed by their health status and concerns about their well being, interactions can pose challenges for pharmacists, especially when exacerbated by conditions often experienced at pharmacies, such as long waiting times, insurance problems that prevent or delay obtaining medication, or perceived disrespect from technicians or pharmacists. It is impossible to treat patients without engaging them directly, and the implication of this reality for pharmacy schools is that students must be made aware that the nature of their work makes it more likely they will be targets of patients' aggression. Colleges and schools of pharmacy will have to pay attention to the growing phenomenon of aggression in the workplace and take appropriate steps to reduce its occurrence at pharmacies. One way to achieve this is to train students to be aware of how perceptions of patients' emotions influence how they communicate and the impact this has on building alliances. Learning to recognize patients' emotional states and responding appropriately, like expressing empathy at the earliest opportunity, for example, can assuage angry feeling and reduce the incidence of patients acting aggressively. Thus, training students to be aware of, and better manage, patients' emotions as well as their own is vital.

When intended as an act of aggression, a patient's refusal to cooperate with a pharmacist's instructions may be rooted in a paternalistic model of care. In this model, the provider lectures the patient, giving instructions that represent the provider's beliefs, with little or no regard for the patient's concerns or perceptions.15 Though well intentioned, paternalism systematically takes control away from the patient, and generally results in resentment.16 Consequently, the patient exercises personal decisions about treatment that may be contrary to the provider's instructions, possibly with dangerous consequences. After the study, many students commented, “Why wouldn't they (patients) follow our advice? We are doing it for their good.” Although their reaction was not surprising given that they were only in their second year of training, it highlights the importance of challenging students' paternalistic views. Second, it signals the need for pharmacists to establish a rapport with their patients, which in turn builds trust. When patients experience pharmacists who are emotionally connected to their experiences, they feel more open to communicate about their experiences. Teaching students to be active empathic listeners will result in pharmacists who demonstrate interest and concern in what patients have to say about their treatment. Third, refusal to cooperate with pharmacists' instructions has dangerous consequences for patients. Patients who demonstrate dissatisfaction by refusing to cooperate with pharmacists' instructions may not achieve expected outcomes and may harm themselves in the process. Pharmacists, therefore, must recognize and manage patients' negative emotional experiences in an effort to establish better working relationships and maximize patient treatment outcomes. Students who are taught to do this will avoid being rendered ineffective by patients whose anger sabotages treatment.

The aggressive incidents the pharmacy students' experienced in practice settings evoked many strong negative feelings. While some were surprised over the incidents, most expressed frustration. These negative emotions have a strong potential to elicit aggression.1-3 Not surprisingly, half of the students expressed anger and more than a third felt like getting even. This is a dangerous recipe for patient treatment outcomes and highlights the need for pharmacy schools to teach students how to monitor and manage their feelings toward patients. The anxiety, fear, and helplessness the students felt over encountering aggression at work is of concern because these types of emotional stress are associated with poor job satisfaction and burnout.17,18 Pharmacy schools must consider preemptive training to help students better cope with this source of frustration when they enter practice.

Finally, almost three quarters of students expressed “no pride” in the profession following aggressive incidents, while a majority experienced “empathy.” This is important and positive because the profession requires empathy for all patients. It demonstrates that even when students were frustrated and angry about patients' aggression, they also empathized with their emotional states. It also means patients can expect to receive the level of care that pharmacists are expected to deliver regardless of how they feel about patients or their work.

The results of this study shed light on the relationship between pharmacy students' personality style, specifically how they react to aggression, and their perception of patients' anger. This informs schools that pharmacists' training should prepare students to deal with potentially aggressive situations. Educational programs must consider the importance of teaching progressive communication, training students to identify patients' emotional states, and developing strategies to cope with negative emotions to benefit patients without unduly stressing pharmacists.

One limitation of this study was that it was student based. Thus, extrapolating the implications to pharmacy practice, though meaningful, may be inaccurate. In addition, this study was survey based, and given the different ways aggression is described in the literature, more qualitative data may be necessary to determine whether what students in the study considered to be an aggressive incident is synonymous with the way aggression is used in research. Finally, a convenience sample was used so the generalizability of the results is limited.

Future research should conduct a qualitative analysis of what constitutes verbal aggression, specifically verbal aggression on the telephone, so training curricula can develop strategies for students to manage this pharmacy workplace phenomenon. In addition, further exploration is needed to better understand why some students view patients' non-cooperation with pharmacists' instructions as aggression. The relationship between the high rate of job dissatisfaction and burnout in pharmacy practice, and pharmacy students' feeling of “no pride” (negative emotions) in the profession following aggressive incidents needs to be examined further. Finally, the high percentage of respondents selecting the “other” ethnic category may be explained by the fact that respondents of multi-ethnic heritage may have had difficulty finding an ethnicity among the choices that represented them.

CONCLUSION

Pharmacy students working in pharmacies experience aggressive incidents with patients. As they communicate with patients in person or on the phone, patients' aggression toward pharmacy students may affect how students in turn relate to other patients and how patients adhere to/follow instructions regarding their medications. Pharmacy students perceived aggression as a normal but violent phenomenon that left them feeling frustrated, angry, and helpless. Although many felt a lack of pride about their work following aggressive incidents they maintained empathy for patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkowitz L. Is criminal violence normative behavior? Hostile and instrumental aggression in violent incidents. J Res Crime Delinq. 1978;15(2):148–161. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkowitz L. Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychol Bull. 1989;106(1):59–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dollard J, Doob LW, Miller NE, Mowrer OH, Sears RR. Frustrations and Aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger BA. Communication Skills for Pharmacists: Building Relationships, Improving Patient Care. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Association; 2005. p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squier RW. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(3):325–339. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipscomb JA, Love CC. Violence toward health care workers: an emerging occupational hazard. J Am Assoc Occupational Health Nurses. 1992;40(5):219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soloff PH, Gutheil TG, Wexler DB. Seclusion and restraint in 1985: a review and update. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 1985;36(6):652–657. doi: 10.1176/ps.36.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zernike W, Sharpe P. Patient aggression in a general hospital setting: do nurses perceive it to be a problem? Int J Nurs Pract. 1998;4(2):126–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1998.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychol Rev. 2001;108(1):273–279. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith-Pittman MH, McKoy YD. Workplace violence in healthcare environments. Nurs Forum. 1999;34(3):5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1999.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell GA. Aggression in clinical settings: nurses' views. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(6):501–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansen G, Dassen T, Moorer P. The perception of aggression. Scand J Caring Sci. 1997;11:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1997.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry AJ, O'Riordan D, Turner M, Mills KL. Survey of aggressive incidents experienced by community mental health staff. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2002;11(2):112–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2002.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holden RJ. Aggression against Nurses. Aust Nurses J. 1985;15(3):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davenport DS. The functions of anger and forgiveness: guidelines for psychotherapy with victims. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1991;28(1):140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rahim H. Talking your way through tough situations. Drug Store News. 2008; 401-000-08-009-H04. Available at: http://www.cedrugstorenews.com/userapp//lessons/lessons_ui.cfm. Accessed April 8, 2010.

- 17.White JW, Smith PH, Koss MP, Figueredo AJ. Intimate partner aggression–what have we learned? Comment on archer. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(5):690–696. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Patterns of burnout among a national sample of public contact workers. J Health Hum Resour Adm. 1984;7(2):189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor B, Barling J. Identifying sources and effects of carer fatigue burnout for mental health Nurses: a qualitative approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2001;13(2):117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-8330.2004.imntaylorb.doc.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]