Abstract

Purpose

The combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy has not been examined in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. We conducted a study of two GM-CSF secreting pancreas cancer cell lines (CG8020/CG2505) as immunotherapy administered alone or in sequence with Cy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Experimental Methods

This was an open label study with two cohorts: A- 30 patients administered a maximum of six doses of CG8020/CG2505 at 21 day intervals; B- 20 patients administered 250 mg/m2 Cy intravenously (IV) one day prior to the same immunotherapy given as in Cohort A. The primary objective was to evaluate safety and duration of immunity. Secondary objectives included time to disease progression (TTP) and median overall survival (OS).

Results

The administration of CG8020/CG2505 alone or in sequence with Cy demonstrated minimal treatment-related toxicity. Median survival in Cohort A and Cohort B were 2.3 and 4.3 months respectively. CD8+ T cell responses to HLA Class I restricted mesothelin epitopes are identified predominantly in patients treated with Cy + CG8020/CG2505 immunotherapy.

Conclusion

GM-CSF secreting pancreas cancer cell lines CG8020/CG2505 alone or in sequence with Cy demonstrated minimal treatment-related toxicity in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Also, mesothelin specific T cell responses are detected/enhanced in some patients treated with CG8020/CG2505 immunotherapy. In addition, Cy modulated immunotherapy resulted in median survival in a Gemzar resistant population similar to chemotherapy alone. These findings support additional investigation of Cy with CG8020/CG2505 immunotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, immunotherapy, immune modulation

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer remains the fourth leading cause of cancer related deaths in the U.S 1. Despite efforts to develop new therapies, locally unresectable and metastatic disease have a median survival of 10-12 months and 3-6 months untreated, respectively 2. Gemcitabine (Gem) is considered the standard first line therapy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer 3. More recent strategies have focused on improving Gem efficacy by combining Gem with other chemotherapy agents or with small molecule drugs 4-12. However, the benefits have been modest. For patients who will inevitably develop disease progression on first line chemotherapy, 5-FU is the only other approved chemotherapy. However, the additional benefit has been questioned with median survival less than 3-4 months 13-15. There have been a number of other chemotherapy agents tested for Gem refractory disease. The results have also been of limited benefit to date 16-20.

Immunotherapy in theory promises unlimited capacity to recognize specific motifs expressed by tumor cells relative to their normal cellular counterparts. A number of proteins are over-expressed by most pancreatic cancers 21-26. Cellular immunotherapies and antibodies designed to target these antigens have been tested in early phase clinical trials 10, 27-32. Some studies have demonstrated post-treatment immune responses to the relevant peptides or whole proteins. However, significant clinical responses have not yet been observed.

Because few tumor antigens expressed by pancreatic tumors have been identified, the whole tumor cell has been the best source of immunogen. We have previously reported the results of a phase I study of an allogeneic, GM-CSF-secreting whole cell tumor immunotherapy approach tested in sequence with adjuvant chemoradiation in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma 33. This approach is based on the concept that certain cytokines are required at the site of the tumor to effectively prime cancer-specific immunity. This study demonstrated a direct correlation between post-immunotherapy in vivo DTH responses to autologous tumor and post-immunotherapy T cell responses to a candidate pancreatic tumor antigen mesothelin 34.

More recent data from our group and others suggest that immune modulating doses of Cy given one day prior to immunotherapy can enhance treatment induced anti-tumor immune responses by inhibiting the CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) 34-36. We report here the first evaluation of GM-CSF secreting pancreatic cancer lines as immunotherapy given either alone or in combination with immune-modulating doses of Cy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

Fifty patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were enrolled at two sites (Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins and Mary Crowley Medical Research Center) between June 6, 2002 and October 16, 2003. Main eligibility criteria included: histologic diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, at least one measurable lesion, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥ 70, CD4+ lymphocytes > 200 cells/mm3, normal hematologic, renal and liver function. Key exclusion criteria included: non-protocol specified treatment within 4 weeks of the first treatment, prior cancer vaccine therapy, HIV seropositivity, systemic corticosteroid use within 4 weeks of the first vaccination, evidence of brain metastases.

Study Design

The first 30 patients enrolled in the study were included in Cohort A (6 treatments alone repeated every 3 weeks). All subsequently enrolled patients were included in Cohort B (6 treatments, preceded by 250 mg/m2 of Cy one day prior to immunotherapy). Following completion of final treatment and follow-up, patients were followed monthly for a maximum of 9 monthly visits. The interventions and data collection schedule is diagrammed in Figure 1.

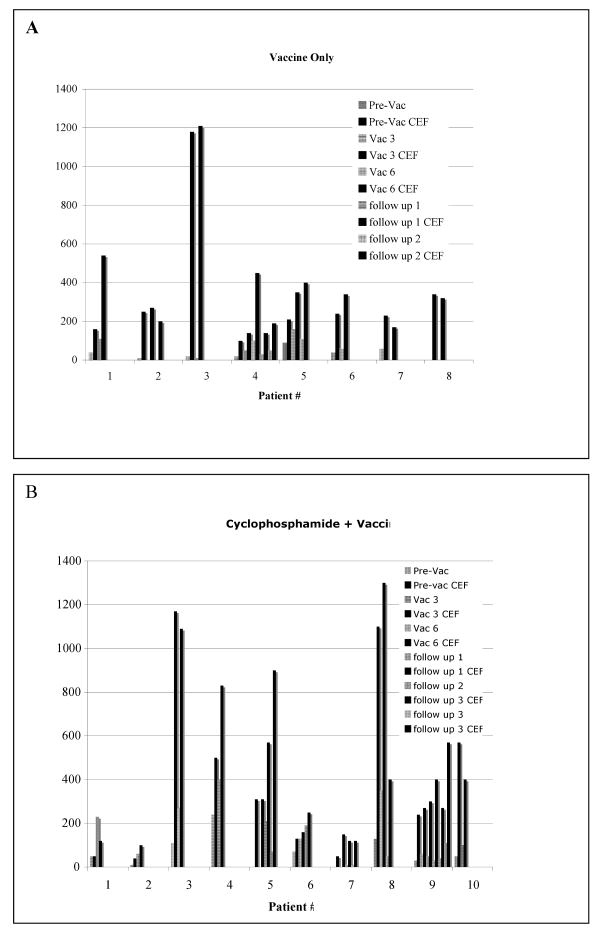

Figure 1. Comparison of the magnitude of CD8+ T cells specific for mesothelin versus the CEF pool of peptides.

An Elispot analysis was performed to determine the number of interferon-gamma secreting T cells specific for mesothelin as described in Table 4. All patient lymphocytes were also assessed for recognition of an HIV negative control peptide and a positive antigen control pool of peptides (CEF pool). Background spots ranged from 0-10 spots/per well as described in Table 4. Graphed is the mesothelin specific T cell response data presented in Table 4 and the corresponding CEF pool specific CD8+ T cell responses. A. Immunotherapy Only Cohort. B. Cyclophosphamide + Immunotherapy Cohort. Striped bars=mesothelin data. Black bars=CEF pool data.

Treatment

CG8020 and CG2505 were formulated as directly injectable products. CG8020 and CG2505 were administered on an outpatient basis. On the day of immunotherapy, vials of CG8020 and CG2505 were removed from the freezer and thawed in a 37°C water bath, drawn into labeled syringes and kept on ice until administration. All injections were given within 60 minutes of thaw. Each treatment consisted of 4-8 intradermal injections (0.5 mL/injection) of CG8020 to deliver a total of approximately 2.5 × 108 cells, and 4-8 intradermal injections (0.5 mL/injection) of CG2505 to deliver approximately 2.5 × 108 cells, for a combined total of approximately 5 × 108 cells per dose.

Assessments of Toxicities

All patients underwent toxicity monitoring every 3 weeks to include history and physical exam, complete blood count, a complete chemistry profile, and serum amylase. Serum was collected for GM-CSF levels before (day 0) and at days 1, 2 3, 4 post treatment one and three for a subset of patients. All adverse events were collected from the day of the first dose of Cy in Cohort B, until 4 weeks after the last treatment. Intensity was evaluated using the NCI common toxicity criteria (Version 2.0).

Immune Monitoring studies

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL)

100 cc of peripheral blood was obtained prior to the first, third, and sixth treatment and at follow-up visits 1,3, 6 and 9 for immune analysis. Pre and post-vaccine PBL were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were washed twice with serum free RPMI-1640. PBL were stored frozen at -180°C in 90% AIM-V media containing 10% DMSO until the day of analysis.

Enrichment of PBL for CD8+ T cells

CD8+ T cells were isolated from thawed PBL using CD8 negative isolation kits according to the manufacturer's directions (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway). Cells were fluorescently stained with CD8-PE antibody (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) to confirm that the population contained CD8+ T cells.

ELISPOT assay

Multi-screen ninety-six well filtration plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated overnight at 4°C with 60μl/well of 10μg/ml anti-hIFN λ mouse monoclonal antibody (Mab) 1-D1K (Mabtech, Nacka, Sweden). Wells were then washed 3 times each with 1×PBS and blocked for 2 hours with T cell media. 1×105 T-2 cells pulsed with peptide (2μg/ml) in 100μl of T cell media were incubated overnight with 1×105 thawed PBL that are enriched for CD8+ T cells in 100μl media on the ELISPOT plates in replicates of three. Following overnight incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the ELISPOT assays were completed as previously reported 34. All time points were assayed in three replicates and reported as the mean number of mesothelin specific CD8+ T cells per 106 total CD8+ T cells.

Pharmacokinetic analysis of serum GM-CSF levels

Serum was separated from whole blood by centrifugation for 10 minutes and frozen in 1 ml aliquots at -80° C until the day of testing. Serum GM-CSF levels for all collection time points were determined by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine Systems) as previously reported 33.

Statistical Considerations

Analyses were performed using data from patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated either with immunotherapy alone or in sequence with Cy. Summary statistics include exact 95% confidence intervals for categorical data and medians, confidence intervals, and ranges for continuous outcomes. The longevity of serum concentration of GM-CSF is evaluated by plotting the mean concentration with 95% confidence intervals over time for a subset of the population. Progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated from the date of the start of treatment. Patients withdrawing from the study for reasons unrelated to PFS or OS are considered censored for that survival outcome at the time of their last visit. The survival outcomes (PFS and OS) are analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier technique that allows for adjustment of the estimators due to censoring. For each treatment regime, the median of each survival outcome is reported with 95% confidence intervals and ranges. The two treatments are compared for each outcome using a log-rank test with a significance level of 0.05.

Peptides

Mesothelin peptides used in these studies were identified by methods previously reported 34. All peptides were purified to >95% purity and synthesized by the Johns Hopkins University Oncology Department Peptide Synthesis Facility according to published sequences. The HLA-A1-binding peptides used were mesothelinA1(310-318) peptide EIDESLIFY and mesothelinA1(429-437) peptide TLDTLTAFY. The HLA-A2 and HLA-A3-binding mesothelin and HIV control peptides have been previously reported 34. Stock solutions (10 mg/ml) of peptides were prepared in 100% DMSO (JT Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) and stored at -80°C until being further diluted into culture medium prior to each assay.

Tetramer Studies

The HLA-A2 tetramers used in these studies were manufactured by Beckman Coulter, Inc. (Fullerton, CA). Phycoeryhtrin (PE)-conjugated tetramers were constructed for the HLA-A2-binding mesothelin peptides MesoA2(20-28) (SLLFLLFSL) and MesoA2(531-539) (VLPLTVAEV) and the HLA-A2-binding tyrosinase peptide YMDGTMSQV. Tetramer staining was performed only when pre- and post-treatment PBL were available. For each timepoint analyzed, 1×106 freshly thawed PBL were resuspended in 50 μl of each HLA-A2 tetramer diluted from 1:10 to 1:60 in PBS/2% FBS (Atlas, Fort Collins, CO) and incubated at 4°C for 40 minutes in the dark. After 40 minutes, 10 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was added and the samples were incubated for another 20 minutes at 4°C in the dark. Stained PBL were washed two times in 3 ml of PBS prior to being fixed in PBS/0.5% formaldehyde (JT Baker) and analyzed on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinsin, San Jose, CA) at the Johns Hopkins University Human Immunology Core Facility. Flow data was further analyzed using Flow Jo (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 50 patients were enrolled in the study and received study treatment (Table 1): 30 patients in Cohort A (CG8020/CG2505 only) and 20 patients in Cohort B (Cy 1 day prior to CG8020/CG2505). The median age was 56 years (56 years in Cohort A, and 61 years in Cohort B), with a range of 37–88 years. At screening, 94% of the patients had stage 4 disease. 15/30 or 50% of patients in cohort A and 13/20 or 65% of patients in cohort B had KPS ≥ 90. Prior pancreatic cancer therapies included pancreaticoduodenectomy surgery (39/50 patients, 78%), radiation (13/50, 26%), and at least one Gem containing chemotherapy (41/50, 82%).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Cohort A | Cohort B | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| Median Age (range) | 56 (37-88) | 61 (38-81) | 56 (37-88) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 19 (63%) | 11 (55%) | 30 (60%) |

| Female | 11 (37%) | 9 (45% | 20 (40%) |

| Ethnic Origin | |||

| 1 | 27 (90%) | 20 (100%) | 47 (94%) |

| 2 | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| 3 | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| 4 | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| KPS | |||

| 70 | 3 (10%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (10%) |

| 80 | 12 (40% | 5 (25%) | 17 (34%) |

| ≥90 | 15 (50%) | 13 (65%) | 28 (56%) |

| Stage | |||

| 3 | 3 (10%) | 0 | 3 (6%) |

| 4 | 27 (90%) | 20 (100%) | 47 (94%) |

| Prior Surgery | 24 (80%) | 15 (75%) | 39 (78%) |

| Prior XRT | 7 (23%) | 6 (30%) | 13 (26%) |

| Prior chemo regimens | |||

| 0 | 6 (20%) | 3 (15%) | 9 (18%) |

| 1 | 8 (27%) | 12 (60%) | 20 (40%) |

| 2 | 11 (37%) | 2 (10%) | 13 (26%) |

| 3 | 5 (17%) | 3 (15%) | 8 (16%) |

Ethnic Origin: 1= white, Caucasian; 2= African American; 3= Hispanic; 4= Asian; KPS= Karnofsky Performance Status

GM-CSF secreting cell lines as immunotherapy is feasible and safe to administer to patients with advanced metastatic pancreatic cancer

A summary of all treatment related adverse events are described in Table 2. All 50 patients received at least one treatment of CG8020 and CG2505, and overall, patients received a median of 2 treatments (2 for Cohort A and 3 for Cohort B). Twenty six out of 26 evaluable patients in cohort A and 20/20 patients in cohort B developed eythema/induration or pain/soreness at the treatment sites following immunotherapy, similar to what was observed in phase I testing 33. These reactions were expected and self limiting, lasting up to one week.

Table 2. Summary of Treatment Related Adverse Events.

| a) injection site reactions (per vaccine) | ||||||

| Vaccine # 1 | Cohort A n=30 | Cohort B n=20 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 18 | 8 | 0 | 18 | 2 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 20 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 11 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccine # 2 | Cohort A n=15 | Cohort B n=15 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 11 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccine # 3 | Cohort A n=9 | Cohort B n=10 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccine # 4 | Cohort A n=7 | Cohort B n=7 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccine # 5 | Cohort A n=5 | Cohort B n=4 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 4 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccine # 6 | Cohort A n=3 | Cohort B n=4 | ||||

| Site Reaction | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 |

| Erythema/Induration | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain/soreness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| b) all other treatment related adverse events | ||||||

| Organ Class | All Grades | Grade 3/4 | ||||

|

Cohort A N=30 (%) |

Cohort B N=20 (%) |

Total N=50 (%) |

Cohort A N=30 (%) |

Cohort B N=20 (%) |

Total N=50 (%) |

|

| Metabolism | ||||||

| dehydration | 1(3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Nervous system | ||||||

| dizziness | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| headache | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| vascular | ||||||

| hot flashes | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| nausea | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| vomiting | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Skin | ||||||

| dry skin | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| night sweats | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| pruritus | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| rash | 1 (3.3) | 2 (10) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| generalized itching | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| musculoskeletal | ||||||

| arthralgia | 1 (3.3) | 2 (10) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| myalgia | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| extremity pain | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| General disorders | ||||||

| asthenia | 6 (20) | 7 (35) | 13 (26) | 1 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) |

| chills | 1 (3.3) | 5 (25) | 6 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| fatigue | 4 (13.3) | 2 (10) | 6 (12) | 1(3.3) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) |

| inflammation | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| injection site discoloration | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| injection site vesicles | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| pyrexia | 5 (16.7) | 3 (15) | 8 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Overall | 24 | 34 | 58 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Pharmacokinetics of Serum GM-CSF

We previously reported the detection of low serum GM-CSF levels that peaked at 48 hours after treatment with the GM-CSF secreting tumor lines in patients receiving the highest dose of cells as adjuvant therapy in the Phase I study 33. Correlative data from the Phase I study provide strong evidence that low serum GM-CSF levels peaking at 24-48 hours following treatment provide an important measure of the bioactivity of this immune based therapy 38. Serum GM-CSF levels were therefore assessed in 16 of the patients (5 from Cohort A and 11 from Cohort B) after treatment one, and in 5 patients (from Cohort B only) after treatment three (Figure 2). The results were similar for each cohort. Mean serum GM-CSF reached peak levels of 26 pg/mL. Measurable levels of GM-CSF were sustained for 4 days after treatment in the majority of patients both after the 1st and 3rd treatments.

Clinical Responses

This was a two cohort, non-randomized study. Of the 50 patients, 13 (26.0%) had stable disease for a duration of 18 weeks (5/30, 16.7% Cohort A, and 8/20, 40.0% Cohort B). The median time to death, as measured from administration of the first treatment dose, was 69 days for Cohort A and 130 days for Cohort B (Table 3). Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival (time from first treatment), by treatment cohort, are shown in Figure 3. Of interest, there was one patient in Cohort B with a history of resected pancreas cancer followed by disease progression to involve the left lobe of her lung who was enrolled with progression disease on Gemcitibine chemotherapy. This patient's progression stabilized on study. She completed all 6 vaccinations and had continued stable disease radiographically. Given the fact that she had only disease involving her left lower lobe of her lung with no interval disease at other sites following her treatment, she underwent a left lower lobectomy with pathology consistent with pancreas cancer. Subsequent follow-up scans continued to demonstrate no evidence of recurrent disease. She eventually died of non-pancreas cancer related illness 25 months after completing immuntherapy.

Table 3. Summary of mesothelin-specific T cell responses in the HLA-A1+/HLA-A2+/HLA-A3+ patients treated with the vaccine alone or in sequence with Cy.

| Patient/HLA | COHORT A mesothelin specific T cells/10e6 CD8 T cells Patients Given Immunotherapy alone |

survival (mo) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre | vaccine 3 | vaccine 6 | follow up | follow 2 | follow up 3 | ||

| 1/(2) | 40 | 110 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.36 |

| 2/(1) | 10 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7.1 |

| 3/(3) | 20 | 10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.36 |

| 4/(3) | 20 | 50 | 100 | 30 | 50 | N/A | 7.9 |

| 5/(1) | 90 | 160 | 110 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 17.6 |

| 6/(2) | 40 | 60 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6.1 |

| 7/(2) | 60 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.7 |

| 8/(2) | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.86 |

| Patient/HLA |

COHORT B mesothelin specific T cells/10e6 CD8 T cells Patients Given Immunotherapy +Cytoxan |

survival (mo) | |||||

| pre | vaccine 3 | vaccine 6 | follow up | follow up 2 | follow up 3 | ||

| 1/(2) | 50 | 230 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.23 |

| 2/(1) | 10 | 60 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 22.5 |

| 3/(2) | 110 | 270 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 4/(2) | 240 | 400 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7.73 |

| 5/(3) | 0 | 0 | 210 | 70 | N/A | N/A | 25+ |

| 6/(3) | 70 | 130 | 190 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8.13 |

| 7/(2) | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | N/A | N/A | 13.07 |

| 8/(2) | 130 | 350 | 50 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.7 |

| 9/(2) | 30 | 60 | 50 | 30 | 40 | 110 | 12.3 |

| 10/(2) | 50 | 100 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.6 |

Pre= pretreatment #1. Treatment cycle #1 = post treatment #1, vaccine #3 = post treatment #3, vaccine # 6=post treatment #6. NA= Not available due to patient progression. The ELISPOT assay was used to determine the # of mesothelin-specific CD8+ T cells specific for the HLA-A1+ epitope, MesoA1(20-28), HLA-A2+ mesothelin epitope MesoA2(530-539), or the HLA-A3 mesothelin(225-234) epitope. All time points for each patient were assayed simultaneously in six replicates and reported as the mean number of mesothelin specific CD8+ T cells per 106 total CD8+ T cells. Background spots were determined using a negative peptide control known to bind to HLA-A1 HIV- Nef(73-87) (QVPLRPMTY), HLA-A2 HIV-gag(77-85)(SLYNTVATL), and HLA-A3 HIV-1NEF (94-102) (QVPLRPMTYK6). Background spots ranged from 0-10/well. A CEF pool was used as a positive control. The CEF pool contains epitopes from CMV, EBV, and influenza A virus proteins that bind to most HLA class I molecules. CEF pool is obtained from NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: (CEF Control Peptide Pool, 9808) from (DAIDS, NIAID). Positive control spots ranged from 40-1300/per well.

Mesothelin-specific immune responses are detected in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer

We previously reported that detection of post-vaccination mesothelin-specific T cell responses correlated with other measures of immune activation and prolonged disease-free survival for patients with resected pancreas cancer treated with immunotherapy 34. We therefore assessed whether this immunotherapy can induce mesothelin-specific T cell responses in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. These pancreatic cancer patients have advanced disease that is thought to impede the induction and maintenance of effective immune responses. Thawed and enriched CD8+ T cells were assayed for production of γ-IFN in response to T2 cells pulsed with HLA Class I restricted mesothelin epitopes by ELISPOT. Lymphocytes for post immunotherapy analysis were available only for patients who did not have disease progression prior to treatment #3 (11/30 patients in cohort A and 12/20 patients in cohort B). Reagents were available for HLA-A1+, A2+, and A3+ patients (8/11 patients in cohort A and 10/12 patients in cohort B). A summary of the ELISPOT data for all 18 patients analyzed is shown in Table 4. Baseline mesothelin specific CD8+ T cells were detected at low levels in the peripheral blood in most patients prior to the first cycle of immunotherapy. However, CD8+ T cell responses to HLA restricted mesothelin epitopes were augmented post cycle 3 and 6 of the therapy predominantly in patients treated with Cy + immunotherapy (9 of 10) as compared with patients treated with immunotherapy alone (4 of 8). CD8+ T cell responses were detected against the positive control CMV/EBV/Influenza A (CEF peptide) pool in all patients treated in both Cohorts (Figure 4). While the analysis to date is limited to HLA- A1+, -A2+ and -A3+ patients, median survival from this subset of patients with induction or enhancement of mesothelin-specific T cell responses treated with immunotherapy alone is 7.6 months versus 10.4 months for patients treated with Cy + immunotherapy.

Table 4. Summary of HLA-A2 tetramer titrations in a subset of HLA-A2+ patients treated with the vaccine alone or in sequence with Cy.

| Patient | Tetramer Titration Patients without Cytoxan | Survival (mo) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MesoA2(531-539) | Tyrosinase | ||||

| pre | vaccine 3 | pre | vaccine 3 | ||

| 4 | 1:60 | 1:60 | 1:10 | 1:10 | 7.9 |

| 6 | 1:40 | >1:60 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 6.1 |

| 7 | 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:10 | 1:20 | 1.7 |

| Patient | Tetramer Titration Patients Given Cytoxan | Survival (mo) | |||

| MesoA2(531-539) | Tyrosinase | ||||

| pre | vaccine 3 | pre | vaccine 3 | ||

| 1 | 1:10 | 1:40 | 1:10 | 1:10 | 3.23 |

| 4 | 1:20 | >1:40 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 7.73 |

| 7 | 1:40 | 1:60 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 13.07 |

| 8 | >1:60 | 1:20 | 1:10 | 1:10 | 3.7 |

| 9 | >1:60 | >1:60 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 12.3 |

| 10 | 1:60 | <1:60 | 1:10 | 1:10 | 2.6 |

Pre = pre-vaccine #1, vaccine 3 = pre-vaccine #3. Patient PBL were labeled with HLA-A2 tetramers as described in the Methods section. Shown are the tetramer dilutions at which detectable tetramer staining was lost.

To further evaluate the quality of mesothelin-specific T cell responses in these subjects, mesothelin-specific T cells from a subset of HLA-A2+ subjects were assessed for avidity by dilutional HLA-A2/Meso(20-28) and HLA-A2/Meso(531-539) tetramer analysis. Tetramer staining was performed at a range of concentrations (1:10 to 1:60) on freshly thawed PBL when banked pre- and post-treatment PBL were available (3 of 5 HLA-A2+ subjects in cohort A and 6 of 7 HLA-A2+ subjects in cohort B). In concordance with the ELISPOT results, mesothelin-specific T cells were detected in both pre- and post-treatment PBL. Similarly, changes in mesothelin-specific T cell frequencies were also observed. The flow cytometry results for 3 representative subjects are shown in Figure 5. Tetramer analysis of both cohort A subject 7 and cohort B subject 7 showed an increase in the frequencies and avidity of mesothelin-specific T cells in post-treatment PBL compared to PBL isolated prior to treatment. In contrast, a decrease in post-treatment mesothelin-specific T cell frequencies was measured in cohort B subject 8. Whereas changes in frequencies of mesothelin-specific T cells were detected, changes in frequencies of T cells specific for tyrosinase, an irrelevant melanoma antigen, were not detected in any of the 9 subjects evaluated. This suggests that the changes measured were not due to time point-related differences in non-specific tetramer staining. Furthermore, mesothelin and tyrosinase-specific T cells were barely detectable in a healthy HLA-A2+ donor resembling the levels of tyrosinase-specific T cells observed in the PBL of subjects on this study (Figure 5). The highest dilution of tetramer at which staining was no longer detectable is also shown for all subjects tested (Table 5). Although the analysis was only performed on a small number of subjects, it is interesting that the post-treatment MesoA2(531-539) tetramer titration correlated with overall survival. Importantly, these tetramer changes appear to be antigen specific since time point differences in tyrosinase tetramer titrations were not observed and were lower than those observed for mesothelin peptide tetramers.

Discussion

This study of allogeneic GM-CSF secreting cell lines as immunotherapy support the following three conclusions. First, the immunotherapy given alone or in combination with immune modulating doses of Cy demonstrated minimal treatment-related toxicity and was feasible to administer to patients with advanced pancreatic cancer following progression on first line chemotherapy. Second, there is a suggestion of enhanced activity when Cy is given prior to immunotherapy based on the higher rate of induction of mesothelin-specific T cell responses as well as longer progression-free and overall survival in the Cy plus immunotherapy cohort. However, this study was not designed to formally test for cohort differences. Third, mesothelin-specific CD8+ T cells can be detected in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and enhanced number and avidity may be associated with longer survival.

This is the first clinical trial testing GM-CSF secreting tumor cell lines as immunotherapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Despite the short survival expected in this patient population, it was possible to evaluate the safety and induction of immune responses to this experimental therapy. The most common adverse event was injection site reactions observed in all assessed patients. Other than injection site reactions, the most frequently reported adverse events involved the gastrointestinal system (e.g., nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting) and general disorders (e.g., fatigue and pyrexia).

Serum GM-CSF levels were also assessed pre- and post treatment for a subset of patients who received either immunotherapy alone or immunotherapy + Cy as an indirect measure of the longevity of the treatment. Serum GM-CSF levels were similar in both cohorts, reaching peak levels 2 days post-treatment. These findings are similar to what was observed in resected subjects receiving this immunotherapy approach and in pre-clinical models evaluating the mechanism of action of this immune based therapy 33, 38-40. These peak levels have also correlated with a systemic eosinophilia that occasionally is associated with biopsy proven systemic rashes due to eosinophil and lymphocyte infiltration 33. Importantly, peak serum GM-CSF levels were consistent following repeated administrations, suggesting that the pancreas cancer cell lines are not rapidly cleared by a repetitive treatment administered every 3 weeks. Additional clinical studies evaluating a larger cohort of patients is necessary to confirm the stability of the pancreatic cancer cell lines at the treatment site following repeated immunizations. It is also possible that patients with advanced pancreatic cancer have a more global immune suppression and are unable to mount an allogeneic immune response capable of rapidly rejecting repetitively injected allogeneic pancreas cancer cells. This is an unlikely circumstance since mesothelin specific T cell responses are detectable in some of these patients. Furthermore, local treatment site reactions, a result of infiltrating lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells, increased with each immunotherapy 33.

This study was not powered to detect significant differences in progression-free and overall survival between the two cohorts. The cohorts are not matched and as such there are imbalances with respect to performance status and prior treatment. With the caveat that the sample size for each group is small, 65% of patients in cohort B versus 50% of patients in cohort A, had a KPS ≥ 90. This would be expected to slightly favor cohort B. The majority of patients in both cohort A (24/30) and cohort B (17/20) had at least one prior chemotherapy with 16/30 patients in cohort A and 5/20 patients in cohort B receiving second or third line chemotherapy. In addition, the majority of patients for both cohorts had stage IV disease. While there was no statistical difference in overall survival and 12 month survival between cohorts, the one year survival of 20% and median overall survival of 4.3 months for subjects in cohort B is at least consistent with published data for second line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer 13-20.

In this study we also show the feasibility of detecting CD8+ T cell responses to HLA restricted mesothelin epitopes. Post treatment responses were measured predominantly in patients who were treated with combined Cy + immunotherapy and who have also demonstrated prolonged survival. Interestingly, baseline T cell responses to mesothelin were detected in a number of patients but did not predict survival benefit. Baseline T cell responses to pancreatic cancer antigens such as mesothelin are likely secondary to the large tumor antigen load from the pre-treatment tumor burden. It is also interesting to note that the baseline response to mesothelin was higher in Cy treated patients and associated with longer survival and may suggest that these cells can be activated. This data is in contrast with our previous findings in patients with resected pancreas cancer who are at risk for recurrent cancer 33. In those patients, baseline mesothelin specific T cells were not detected. In addition, it is possible that the vaccine if given with immune modulating agents such as Cy, can alter the avidity of the T cell responses in favor of higher activity even when the total number of T cells is low. The metastatic patient population is one of the more difficult subjects in which to study immune responses due to their advanced stage of disease and rapid progression. However, despite this challenge, this study demonstrates the ability to detect and sometimes enhance the avidity of pancreatic cancer antigens. This study provides the feasibility upon which to begin combining other more specific and potent immune enhancing agents with this vaccine. Additional clinical studies are also warranted to determine whether the induction or change in mesothelin-specific T cell responses can predict which patients will benefit from this immune based therapy. Additional studies are also required to assess whether there are functional differences between the baseline and post-therapy mesothelin-specific T cell populations.

In conclusion, this immune based therapy is safe and feasible to administer to patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who have progressed on first line chemotherapy. These data suggest that CG8020/CG2505 given in sequence with Cy results in anti-tumor activity that is similar to reported second line chemotherapy. In addition, mesothelin-specific CD8+ T cell responses can be detected in stage 4 patients and may correlate with overall survival. This study provides the foundation for integrating immunotherapy with other targeted therapies for the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ferdynand Kos and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at John's Hopkins Human Immunology Core for their assistance with the tetramer analyses. We would also like to thank Dr. Sanje Khare and the the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at John's Hopkins Peptide Synthesis Facility for his assistance with synthesizing the peptides used in the immunologic studies.

Supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute K23CA093566-01A1 (D.A.L), P50CA62924 (E.M.J), RO1CA88058 (E.M.J) and by Cell Genesys, Inc. South San Francisco, CA.

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo CJ, Pluth-Yeo T, Hruban R, et al. Cancer of the Pancreas. In: DeVita VT, editor. Principles and Practice of Oncology. Seventh. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co; 2005. pp. 945–986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Cripps MC, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, et al. Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3776–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tempero M, Plunkett W, van Haperen VR, et al. Randomized phase II comparison of dose intense Gemcitabine: thirty minute infusion and fixed dose infusion in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3402–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Alfa GK, Letourneau R, Harker G, et al. Randomized phase III study of exatecan and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in untreated advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;27:4441–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oettle H, Richards D, Ramanathan RK, et al. A phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1639–45. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong HQ, Rosenberg A, LoBuglio A, et al. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, in combination with Gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic Cancer: A multicenter phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2610–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared to gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko A, Dito E, Schillinger B, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Phase II study of fixed dose rate gemcitabine with cisplatin for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:379–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.8267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeCaprio JA, Mayer RJ, Gonin R, Arbuck SG. Fluorouracil and high dose leukovorin in previously untreated patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:2128–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.12.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crown J, Casper ES, Botet J, Murray P, Kelsen DP. Lack of efficacy of high dose leukovorin and fluorouracil in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1682–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.9.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothenberg ML, Benedetti JK, Macdonald JS, et al. Phase II trial of 5-Fluorouracil plus eniluracil in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1576–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kindler HL. Pancreatic cancer: an update. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:170–6. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burris HA, Rivkin S, Reynolds R, et al. Phase II trial of oral rubitecan in previously treated pancreatic cancer patients. Oncologist. 2005;10:183–90. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-3-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulrich-Pur H, Raderer M, Verena Kornek G, et al. Irinotecan plus raltitrexed vs. raltitrexed alone in patients with gemcitabine-pretreated advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1180–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozuch P, Grossbard ML, Barzdins A, et al. Irinotecan combined with gemcitabine, 5-Fluorouracil, Leukovorin and cisplatin (G-FLIP) is an effective and non-cross resistant treatment for chemotherapy refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2001;6:488–95. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reni M, Panucci MG, Passoni P, et al. Salvage chemotherapy with mitomycin, docetaxel and irinotecan (MDI regimen) in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase I and II trial. Cancer Invest. 2004;22:688–96. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200032929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bos JL. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hruban RH, Van Mansfeld AD, Offerhaus GJ, et al. K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Path. 1993;143:545–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gjertsen MK, Bakka A, Breivik J, et al. Vaccination with mutant ras peptides and induction of T-cell responsiveness in pancreatic carcinoma patients carrying the corresponding ras mutation. Lancet. 1995;346:1399–1400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn OJ, Jerome KR, Henderson RA, et al. MUC-1 epithelial tumor mucin-based immunity and vaccines. Immunol Rev. 1995;145:61–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apostopopoulos V, McKenzie IF. Cellular mucins: targets for immunotherapy. Crit Rev Immunol. 1994;14:293–309. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v14.i3-4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammarstrom S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:67–81. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kindler HL, Friberg G, Singh DA, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8033–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse M, Clay T, Hobeika A, et al. Phase I study of immunization with dendritic cells modified with fowlpox encoding carcinoembryonic antigen and costimulatory molecules. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3017–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramanathan RK, Lee KM, McKolanis J, et al. A phase I study of a MUC1 vaccine composed of different doses of MUC1 peptide with SB-AS2 adjuvant in resected and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:254–64. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0581-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilliam AD, Watson SA. G17DT: an anti-gastrin immunogen for the treatment of gastrointestinal malignancy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:397–404. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris JC, Gilliam AD, McKenzie AJ, et al. The biological and therapeutic importance of gastrin gene expression in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5624–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall JL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. Phase I study of sequential vaccinations with fowlpox-CEA (6D)- TRICOM alone or sequentially with vaccinia-CEA (6D)- TRICOM, with and without granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, in patients with carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:720–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffee EM, Hruban R, Biedrzycki B, et al. A Novel Allogeneic GM-CSF Secreting Tumor Vaccine for Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase I Trial of Safety and Immune Activation. J of Clin Oncol. 2001;19:145–156. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas AM, Santarsiero LM, Lutz ER, et al. Mesothelin-specific CD8+ T cell responses provide evidence of in vivo cross priming by antigen presenting cells in vaccinated pancreatic cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2004;200:297–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berd D, Maguire H, Mastrangelo M. Induction of cell-mediated immunity to autologous melanoma cells and regression of metastases after treatment with a melanoma cell vaccine preceded by cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2572–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmberg L, Sandmaier B. Theratope vaccine. Exp Op Biol Ther. 2001;1:881–91. doi: 10.1517/14712598.1.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ercolini AM, Ladle BH, Manning EA, et al. Recruitment of latent pools of high avidity CD8+ T cells to the antitumor immune response. J Ex Med. 2005;201:1591–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffee EM, Thomas MC, Huang AYC, Hauda KM, Levitsky HI, Pardoll DM. Enhanced immune priming with spatial distribution of paracrine cytokine vaccines. J Immunother. 1996;19:52–60. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine GM-CSF stimulates potent, specific and long lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3539–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas MC, Greten T, Jaffee EM. Vaccination with allogeneic tumor cells induces specific anti-tumor immunity. Human Gene Therapy. 1998;9:835–43. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.6-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.