Preface

Most natural environments harbor a stunningly diverse collection of microbial species. Within these communities, bacteria compete with their neighbors for space and resources. Laboratory experiments with pure and mixed cultures have revealed many active mechanisms by which bacteria can impair or kill other microbes. Additionally, a growing body of theoretical and experimental population studies indicate that the interactions within and between bacterial species can profoundly impact the outcome of competition in nature. The next challenge is to integrate the findings of these laboratory and theoretical studies, and to evaluate the predictions they generate in more natural settings.

Introduction

Examples of true charity and altruism in human societies are highly lauded, and rightfully so, but are far from the norm. Competition is a fact of modern life, with individuals and institutions vying to gain advantage in terms of finances, material resources, and status. In capitalist societies, competition is thought to continually hone the attributes of competing entities, improving their efficiency and defining their activities and structure. The high level of competition in human society in many ways mirrors the comparatively ancient and complex interactions observed at virtually every level in the natural world. The battle for resources through which organisms survive and pass on genes to the next generation can often be fierce and unforgiving. This leads to natural selection, which provides the driving force for innovation and diversification between competing organisms 1.

In animals and plants, there are a large number of well studied examples of populations which are held in balance, or driven to transition, by competitive forces. Connell’s barnacles provide a classic example 2. He found that in intertidal zones in Scotland, Balanus barnacles were always found closest to the shore, while Chthamalus barnacles grew further up the rocks. If he experimentally removed the Balanus barnacles from the lower areas, Chthamalus could grow there, but upon reintroduction of Balanus, Chthamalus would eventually be crowded out by the more competitive Balanus. However, Balanus could not grow further up the rocks, due to desiccation sensitivity. Thus, the habitat of Chthamalus was limited to areas where it could escape from competition with Balanus, an example of competitive exclusion.

Similarly, most microorganisms face a constant battle for resources. Vast numbers of microbes are present in all but the most rarified environments. Tremendous microbial diversity has been revealed by new molecular methodologies such as metagenomic sequencing and deep microbial tag sequencing 3, 4. These approaches and others have begun to reveal that underlying the numerically dominant microbial populations is a highly diverse, low-abundance population (described as the rare biosphere, see 3 ). Members of the rare biosphere that are amplified under favorable conditions to which they are pre-adapted can give rise to discrete, abundant populations. The potential pool of microbial competitors is therefore vast, and a wide range of mechanisms can be responsible for the emergence and radiation of dominant microbial populations.

Nutritional resources are a focal point of microbial competition. Jacques Monod, a pioneer in the study of bacterial growth kinetics, first demonstrated the relationship between limiting nutrient concentrations and bacterial growth. In defined medium, in which all but one isolated nutrient was provided in excess, he demonstrated that “total growth”, or bacterial growth yield, is linearly dependent on the initial concentration of the limiting nutrient 5. He then mathematically incorporated this relationship into the equation for exponential bacterial growth, thereby providing a model for the relationship between growth rate and the concentration of a limiting nutrient, an equation similar to the Michaelis-Menton representation of enzyme kinetics 5, 6. Monod’s equations were derived from extrapolations of data obtained from bacterial grown in batch cultures, but he proposed the method of continuous growth which was later used to verify many of his predictions 6.

Tilman later employed Monod kinetics for examining the competition between two different types of algal populations, as a function of limiting resource ratios 7. This resource ratio competition model proposed that the availability and individual demand for and rate of consumption of nutrients will determine the predominance of different taxa. Under certain ratios of nutrient concentrations, competing microbes can stably coexist, while under other conditions, specific taxa can be outcompeted due to acute nutrient limitation. Over time, consumption of limiting nutrients will shape the course of competition. These same principles have been applied to plant and animal communities, and they clearly explain some of the basic dynamics between competing organisms 8, 9. More recently, the impact of limiting resources on bacterial competition has been studied for a wider range of growth substrates and population structures 10, 11.

Collectively this “resource ratio” model of competitive interactions views all of the vacillations of microbial lineages through a nutritional framework. Although this provides a conceptual foundation for predicting the outcomes of microbial competition, it cannot, on its own, encapsulate the diversity of active mechanisms by which certain microbes compete (for examples, see Figure 1). Microorganisms cannot be viewed as passive nutritional sinks, but rather have evolved numerous strategies to augment their acquisition of resources. Activities including motility, antibiotic production, and coordinated behavior can tip the competitive balance, resulting in outcomes that significantly differ from those predicted by resource abundance alone. This review will focus on these active mechanisms of competition. We will first consider the concepts of intraspecies and interspecies competition, and how competitive interactions evolve among different groups of microbes. This will be followed by discussion of several specific mechanisms of microbial competition.

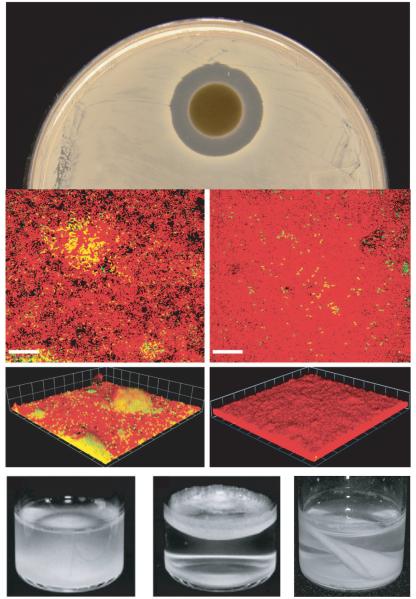

Figure 1. Examples of interference competition between bacterial species.

Top panel:. Many bacterial species produce antimicrobial toxins which facilitate interference competition with other species; pictured is a zone of inhbition in a lawn of Bacillus subtilis surrounding a paper disk soaked with culture supernatant from Burkholderia thailandensis, an antimicrobial producer (picture courtesy B. Duerkop). Middle panel: In biofilm cocultures, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (red cells) blankets the surface of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (green cells- overlay of the two cells is yellow). Biomass of A. tumefaciens decreases in the biofilms over time (left panel represents 24 h growth, right is 164 h), in a mechanism at least partly dependent on quorum sensing by P. aeruginosa (See box 2). Figure reproduced with permission from 58. Bottom panel: Overproduction of EPS by mutant strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens (middle, compared to the parent at left) enables these organisms to position themselves in the favorable environment of the air-liquid interface of liquid cultures, where oxygen is more plentiful. However, EPS production is a phenotype vulnerable to social cheating. If sufficient cheaters that fail to produce EPS accumulate in the floating mat, it will collapse (right). Left and middle panels reproduced with modification from 29, right panel courtesy P. Rainey.

Bacterial competition and cooperation

Research into interspecies competitive strategies has revealed that there are diverse mechanisms by which bacterial species can coexist with, or dominate, other organisms competing for the same pool of resources. As our mechanistic understanding of these interactions progresses, microbiologists are beginning to apply this knowledge towards understanding the emergence and decline of microbial lineages in natural communities. Bacteria also engage in intraspecies competition and can participate in cooperative behaviors. In complex communities, these intraspecies processes can influence interspecies interactions, including facilitating competitive strategies that require cooperation between individuals. We begin our consideration of competition in microbial communities with observations pertaining to bacterial populations, and provide an introduction to how these processes may impact interspecies interactions.

Competition and diversification within bacterial populations

In a well-mixed environment to which the input of new nutrients is minimal, such as a shaking liquid bacterial culture, individuals with similar nutritional requirements, such as members of the same population, will be in competition for acquisition of these nutrients as they become depleted by the growing population. In an environment providing multiple ecological niches, such as a static liquid culture or a biofilm, competition can lead to selection for variants that are better suited to colonize these alternative niches 12-14. For many bacterial species, the combination of rapid growth rates and large population sizes results in the introduction of many unique mutations, even if they occur at low frequencies. Some mutations give rise to variants that are adapted to particular niches and are maintained by negative frequency-dependent selection. For example, static cultures of Pseudomonas fluorescens generate several niche-specialized variants 15. One kind of variant overproduces extracellular polysaccharide (EPS), enabling the variant to float on the surface of the cultures, thus improving access to oxygen. However, this variant suffers if it becomes too dominant; the mats can become too thick to float, and then sink to the bottom of the culture.

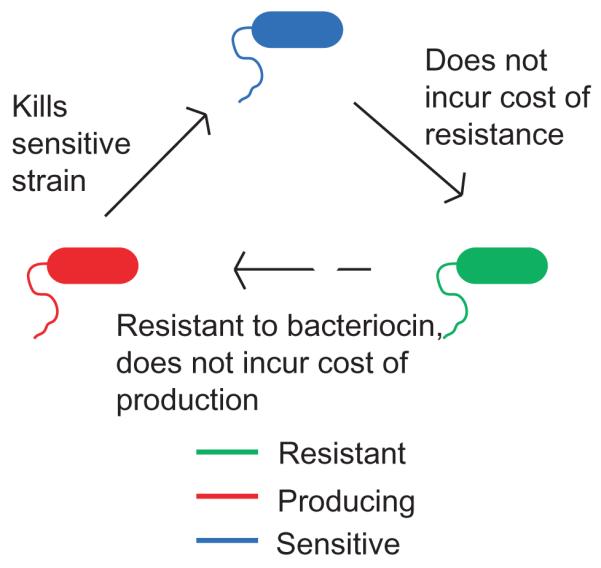

An additional mechanism that may contribute to the maintenance of diversity is the formation of non-transitive competition networks. A non-transitive interaction network resembles the game of rock-paper-scissors; species A dominates species B, which out-competes C, which in turn out-competes A. A classic example of this kind of network that has been used for theoretical and experimental studies is a set of related E. coli strains that either (i) produce (Figure 2, in red), (ii) are sensitive to (Figure 2, blue), or (iii) are resistant (Figure 2, green) to but do not produce molecules toxic to other cells called colicins. Interestingly, in both theoretical models and experimental studies with defined mixtures of E. coli strains, the three types of strains persist only when the environment they inhabit is structured, creating individual niches; in a well-mixed environment, the resistant, non-colicin producer quickly becomes dominant and excludes the others 16, 17. Competitive exclusion is also predicted to occur if the organisms are highly motile, which essentially provides a mechanism for mixing 18. The findings from this E. coli model system have been extended to multispecies systems in recent studies on the spatial structure-dependent coexistence in biofilms of three different soil species; these species, an antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain P1, a resistant Raoultella ornithinolytica strain R1 and a sensitive Brevibacillus borstelensis strain S1, also seem to constitute a non-transitive competition network. 19

Figure 2. Non-transitive competition networks.

A model Escherichia coli non-transitive competition network, first described in ref. 17. A strain producing a colicin toxin (red) outcompetes a sensitive strain (blue), which outcompetes a resistant strain (green), which in turn outcompetes the producing strain.

One potential consequence of the diversification of a bacterial population that remains to be explicitly tested is whether there is an increase in the competitiveness of a diverse population against other species. One mechanism by which this could occur is if a diverse population can rapidly colonize new niches when they arise. Individuals of another species would then have fewer unoccupied niches in which to gain a foothold. For example, the increased ability to occupy new niches as a result of diversification could explain the widespread distribution of Prochlorococcus in the oceans. On a global scale, a variety of phylogenetically resolvable “ecotypes” of this organism have been described with distinct physiological characteristics such as adaptations to high or low light 20. Fine scale diversity such as differences in phage resistance or the ability to efficiently take up particular nitrogen sources has also been detected in Prochlorococcus populations 21, 22. This microdiversity, which is predicted to result from both the accumulation of mutations in particular lineages and from phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer, likely contributes to the evolutionary success of this organism, one of the most abundant species on earth 20, 23.

Cooperation in bacterial populations

Although individuals of the same species can clearly compete with each other, there is a growing appreciation that bacteria also engage in multicellular level behaviors that require cooperation. Quorum sensing, which involves the perception of and response to extracellular signals, is one example of a process that can be operative in the context of multicellular assemblies (See Box 2). In many cases, quorum sensing is thought to regulate processes that are primarily advantageous when expressed by a group of bacteria (although it could also potentially be used by single cells in a diffusion-limited environment) 24.

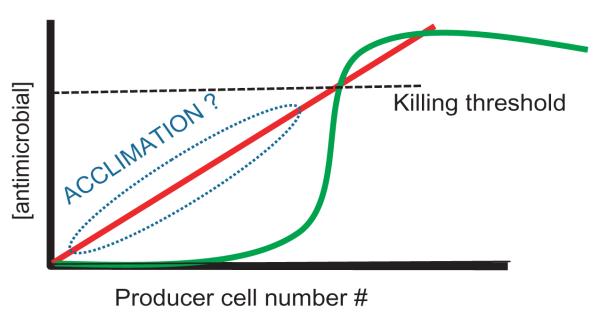

Box 2. Quorum sensing and microbial competition.

Several antimicrobial mechanisms employed by bacteria use secreted compounds to kill or impair neighboring target cells. One might imagine that a single microbial cell producing such factors would be engaging in a futile process as local extracellular killing concentrations could not be achieved. In fact, basal production of such factors under these circumstances could be damaging to the producer. Recent work has highlighted the roles of certain antimicrobials in eliciting responses from target species (See Box 1). Sub-inhibitory levels of an antimicrobial could induce a physiologically tolerant state in target species. How might a microbe both ensure delivery of a killing (or fully inhibiting) dose and prevent the acquisition of tolerance? One possible mechanism would involve quorum sensing. The release of antimicrobials would be delayed until a local quorum is achieved, ensuring the presence of sufficient cell numbers, and thus the production of fully inhibitory antimicrobial levels, for the prevailing diffusion environment. This is represented schematically in the graph depicting the local antimicrobial concentration on the Y-axis vs the number of local cells producing this antimicrobial on the x-axis. The red line depicts continuous antimicrobial production regardless of population size. At low microbial population densities, the extracellular concentration of antimicrobials would be sub-inhibitory to target populations, perhaps acclimating those populations and enabling them to develop tolerance. The green line depicts quorum sensing-regulated antimicrobial production. At a critical population level, a quorum is achieved resulting in the production and release of the antimicrobial, minimizing the likelihood of tolerance by target populations. Not surprisingly, regulation of antimicrobial functions by quorum sensing is widespread in many species (see Table 1).

While it makes intuitive sense that bacterial populations could evolve competitive strategies at the group level, the evolutionary mechanisms that select for and maintain traits that benefit groups, rather than individuals, are not obvious. The clonal nature of many bacterial populations is thought to facilitate the evolution of cooperative behaviors via kin selection 25. However, one potential problem is that if an individual in a population can benefit from the cooperative traits expressed by its neighbors without expressing the trait itself, cooperation can break down and ‘social cheaters’ can emerge. Studies of pure cultures indicate that these social cheaters arise for several bacterial species 26. For example, when P. aeruginosa is grown under conditions requiring quorum sensing-regulated extracellular proteases, social cheaters with mutations in lasR, the central quorum sensing regulator, accumulate within 100 generations 27. These cheaters benefit from the protease activity of the enzymes secreted by their neighbors without expending the energy required to produce and secrete the enzymes themselves. Further experiments confirmed that despite the pleiotropic effects of a lasR mutation, the mutant strains grew faster than wt cells when present as a minority population in a coculture under protease-requiring conditions 27. Another study, using similar culture conditions, confirmed that both lasR mutants, that are “signal blind”, and mutants deficient in signal production had higher fitness compared to the wt parent strain when they were present as a minority in the population 28. Similarly, in the static cultures of P. fluorescens described above, production of the EPS enabling cells to float on the surface of the culture and obtain better access to oxygen is an energy-expensive process that is vulnerable to cheating; social cheaters deficient in EPS synthesis arise and colonize the air-liquid interface by capitalizing on the EPS that is produced by their neighbors (Figure 1, bottom panel)29.

One natural environment in which social cheating may occur is in the lungs of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients chronically infected with P. aeruginosa. A comparison of P. aeruginosa longitudinal isolates obtained from different patients over the course of chronic infection revealed that late stage isolates from 18 of 29 patients sampled harbored mutations in lasR 30. LasR regulates numerous extracellular functions including proteases, several antimicrobial molecules such as hydrogen cyanide, the cytochrome inhibitor HQNO, and the phenazine antimicrobial pyocyanin, which is toxic both to microbes and eukaryotic cells. Individuals harboring mutations in lasR may therefore benefit from production of these extracellular products by their wt neighbors. However, it is also possible that loss of lasR actually confers some selective advantage under the specific conditions of chronic infection 31. Additional work is needed to precisely determine if lasR mutants arise as a consequence of social cheating in this environment.

Some mechanism must be responsible for limiting cheating in many natural microbial populations, because group behaviors appear to be widespread. One major difference between most natural settings and the experiments where cheating was observed is the potential for interactions between different species or different populations of the same species. In experiments where cheating has been studied, the cultures consist of an initially clonal population of a single species. Theoretical studies predict that one mechanism by which cooperative behaviors can be maintained in spite of the potential for cheating is through competition between groups (i.e., either populations or communities of different species) 32. If the competition between groups is greater than that within groups, cooperative traits that confer a group benefit will be favored, and groups that harbor social cheaters that detract from the overall competitiveness of the group will be disadvantaged 33-35. Although not well studied in the context of microorganisms, cheating can also be minimized if cooperators can discriminate between cheaters and fellow cooperators, or if cheating is actively punished 33.

Co-evolution and interspecies competition

Although it is well established that single-species populations of bacteria can evolve over time (e.g. 13, 15), relatively few studies have examined the potential for co-evolution in mixed-species environments. In the macroecological world, co-evolution between competitors, between pathogens and hosts, and between mutualists from different species has been repeatedly observed. For example, resistance to disease in plants is mediated in part by genes known as R-genes that recognize particular pathogen proteins; pathogens can subvert disease resistance if they no longer produce these proteins, but R-gene specificity can evolve in response to exposure to new or altered pathogen proteins, resulting in an evolutionary “arms race” 36. Given that competition is a powerful selective pressure, similar arms races could potentially develop between bacterial species, as each responds to new competitive determinants deployed by the other.

Co-evolution of two bacterial species has recently been directly demonstrated for a commensal interaction in which one organism, P. putida, depends on the partner organism Acinetobacter sp. strain C6 in order to grow on benzyl alcohol as a sole carbon source37, 38. If the two species are cultured together as biofilms on benzyl alcohol, P. putida mutants accumulate that have an increased ability to attach to Acinetobacter cells 37. This leads to greater overall growth yield in the biofilm co-cultures, despite having a detrimental effect on the growth of Acinetobacter.

Indirect evidence for coevolution of competitive interactions between bacterial species can be found among organisms colonizing the human oral cavity. For example, clinical studies have found that patients colonized by Streptococcus oligofermentans have a reduced incidence of dental caries, caused by S. mutans, which prompted an investigation of the interactions between these species in vitro 39. S. mutans is known to inhibit the growth of many other oral species by producing lactic acid from fermentable carbohydrates present in the host diet 40. Interestingly, S. oligofermentans has developed the counter-offensive strategy of using the S. mutans-produced lactic acid to generate hydrogen peroxide, which is in turn inhibitory to S. mutans 39.

Mechanisms of bacterial competition: The role of resources

Nicholson loosely categorized competition for a limiting resource into two broad groups, scramble and contest 41. Scramble competition, also called exploitation competition, involves rapid utilization of the limiting resource(s) without direct interaction between competitors. Contest competition (or interference competition) involves direct, antagonistic interactions between competitors, with the “winner” appropriating the resource(s). E.O. Wilson likened scramble competition to a group of young boys scrambling for pennies dropped on a floor and contest competition to a fight between the boys, with the winner taking all the pennies 42. Both strategies are likely employed in the microbial world.

Most research into competition between bacterial species has focused on elucidating the biochemical mechanisms underlying different interactions, and generally assumes that competition occurs between individual cells. However, the competitive mechanisms available to a single cell may differ from those available to an individual surrounded by a population of its near kin, because of the potential for competitive strategies to evolve requiring cooperative behavior. Below, we review several active competitive strategies described for bacteria, and highlight examples where population-level processes have been shown to be important.

Protecting the supply lines

As shown by the Monod experiments mentioned above, bacterial competition can often be framed in the context of nutrition – access to and protection of growth substrates. Antimicrobial production, space competition, predation and even a rapid growth rate can all be interpreted as a drive to maximize nutrient uptake by one organism at the expense of another. However, several mechanisms of competition function directly to actively restrict or remove a nutrient from one organism and supply it to another. For example, carbon and phosphorus sequestration by polyphosphate accumulating organisms in certain wastewater treatment configurations facilitates their dominance over other species 43. An additional example of this effect can be observed in the struggle to acquire iron.

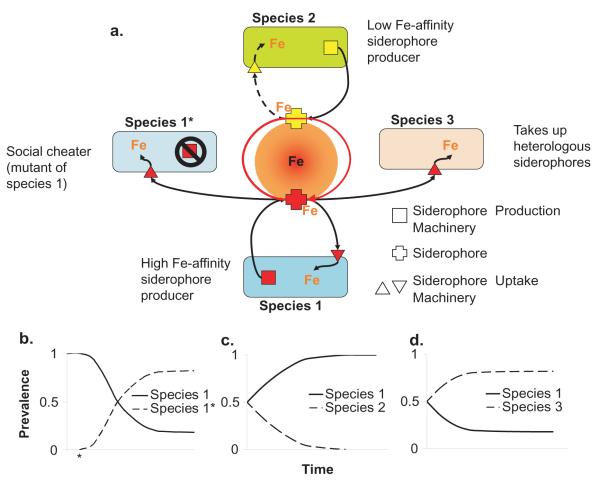

The production, release, and uptake of iron scavenging molecules called siderophores is a major microbial mechanism for iron acquisition 44 (See Figure 3), and numerous examples of siderophore-mediated interspecies competition have been described. Many bacterial species have the ability to utilize heterologous siderophores, shifting the cost of production to another organism and simultaneously sequestering iron away from the siderophore-producer 45 (Figure 3d). Differences in the iron binding affinities of siderophores produced by different species can also mediate competition (Figure 3c). Joshi and colleagues have shown that the addition of a high affinity siderophore to a culture of a rhizosphere-colonizing bacterium that produces a lower affinity siderophore diminishes the ability of this strain to grow in low iron conditions 46. Robust growth is restored by the addition of iron to the medium implying that this bacterium could be outcompeted by the presence of another organism that produces a high-affinity siderophore 46. In co-cultures of P. aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia, the siderophore ornibactin sequesters enough iron from P. aeruginosa to induce expression of genes known to be regulated by low levels of iron 47.

Figure 3. Simplified models of siderophore mediated bacterial competition.

a | Three competitive scenarios in iron limiting conditions where the utilization of a siderophore is necessary for iron acquisition. Species 1* represents a cheater of Species 1 that has lost the ability to produce siderophores but maintains the ability to utilize siderophores produced by cooperating individuals. Species 1 produces a higher affinity siderophore than does Species 2, which allows Species 1 to monopolize the available iron.. Competition between Species 1 and Species 3 is analogous to that between Species 1 and 1*, however, Species 3 has evolved the ability to utilize the heterologously produced siderophore of Species 1 and never had the ability to produce this siderophore. b | The predicted outcome of competition between Species 1 and Species 1* in iron limiting conditions. The * along the x-axis of the graph indicates the mutational event that eliminates the ability of Species 1* to produce the siderophore resulting in the cheating phenotype. c | The predicted outcome of competition between Species 1 and Species 2 , and d | the predicted outcome of competition between Species 1 and 3.

Additionally, siderophore production is an important example of a competitive mechanism that involves a cooperative behavior. Because siderophores are secreted molecules (public goods) that are costly to produce, siderophore producing populations are vulnerable to social cheating by individuals that lose the ability to make these iron-binding products but maintain the capacity to take them up 48 (Figure 3b). Generally, the long-term evolutionary dynamics of siderophore-mediated interspecies interactions remain to be explored. One recent study found that competition for iron between Staphylococcus aureus and P. aeruginosa influenced the evolutionary stability of siderophore production by P. aeruginosa 49. In mixed cultures, P. aeruginosa can lyse S. aureus, liberating free iron 50. However, viable S. aureus also compete with P. aeruginosa for free iron. In iron-limited mixed cultures with S. aureus, siderophore cheaters of P. aeruginosa arose more frequently than when free iron was provided, and also more frequently than in iron-limited pure cultures of P. aeruginosa 49. Thus, interspecies competition influenced intraspecies competition by increasing the selection pressure leading to the accumulation of social cheaters 49.

Taking and Holding the High Ground

A critical aspect of many competitive interactions is stable positioning at favorable sites in the environment. Obtaining access to favorable locations requires either colonizing new niches as they become available (scrambling), or actively displacing existing colonizers (contest). A number of species enhance their chances of winning the scramble to colonize newly available spaces by producing adhesins or receptors that bind to specific surface features. For example, in the human oral cavity, some bacteria specifically bind and colonize the host-derived pellicle coating tooth surfaces, while other species become established by expressing surface-exposed receptors that specifically recognize carbohydrates presented on the exterior of the primary surface colonizers 51. Clearing a space to colonize by eliminating prior residents can be accomplished by production of antimicrobials (discussed further below in “Calling out the artillery”) or by production of molecules that facilitate competitors’ dispersal without actually killing them. P. aeruginosa, for example, produces at least two molecules shown to stimulate dispersal of other species from established biofilms; rhamnolipid, shown to be active against biofilms of Bordetella bronchiseptica 52, and the fatty acid cis-2-decenoic acid, which stimulated dispersal by a number of other species 53.

Once a bacterium or bacterial population is established at a favorable location, long term persistence requires mechanisms for preventing encroachment by potential competitors. Several Lactobacillus species, studied for their ability to favorably influence human health as “probiotics”, can bind to cultured human epithelial cells and then produce specific exterior glycoproteins that prevent subsequent attachment of potential pathogens, including E. coli and Salmonella enterica 54-56. The production of EPS may also serve to protect a colonized niche from encroachment by competitors; a recent modeling study predicts that EPS producers in a mixed-species biofilm can smother competitors, and use polymer production to push themselves into the more nutrient and oxygen-rich regions at the air-liquid interface 57.

To fight or flee: motility in microbial competition

Motility has been shown to affect the ability of some bacteria to compete, while other bacteria apparently use active locomotion to avoid competition. For example, in co-inoculated biofilms, P. aeruginosa uses motility, among other traits, to blanket Agrobacterium tumefaciens 58 (also highlighted in Fig. 1). Interestingly, at initial stages of colonization in the presence of P. aeruginosa, a non-motile A. tumefaciens mutant accumulated greater adherent biomass than the motile wild-type strain, possibly indicating that wild type A. tumefaciens actively evades contact with P. aeruginosa 58. Wild type P. aeruginosa also uses motility to out compete its own non-motile variants for more suitable regions in biofilms. The motile P. aeruginosa migrate to the top of non-motile microcolonies, forming the caps of tall, mushroom-like structures 59. The motile cells thus access more oxygenated and nutrient rich regions of the culture 59. Motility is also critical for efficient predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus and Myxococcus xanthus. In B. bacteriovorus a functional flagellar motor is necessary for efficient release from the prey bacteria 60. In M. xanthus, the adventurous motility system is necessary for predation 61.

Another important aspect of bacterial motility is its contribution to dispersal. Highly motile organisms that rapidly disperse into the surrounding environment may be less likely to interact with others of the same species, either via competition or cooperation 18. As a result, highly motile organisms will be more likely to encounter potential competitors as individuals, rather than in the context of a population of closely related organisms, thereby restricting their options for competitive strategies. However, some species may circumvent this problem by traveling in groups; swarming motility in numerous species 62 and social motility in M. xanthus 63 both involve concerted movements of multiple individuals across surfaces.

Calling out the artillery

The most intensively studied mechanism of bacterial competition is the production of small antimicrobial compounds. Although some recent literature calls into question the role of antibiotics as bacterial growth inhibitors in the environment (see Box 1), extensive in situ studies on a number of antibiotics have verified their importance in mediating competition in an antimicrobial capacity (for an example, see 64). Antimicrobial compounds can mediate competition between different species, between related strains of the same species, and also between genetically identical individuals in a population. Additionally, the outcome of antimicrobial production will clearly be affected by the context in which the compound(s) is produced. To effectively inhibit competitors, the antibiotic(s) must be produced in sufficient quantity, and this may require the concerted effort of a population. Accordingly, antibiotic production often is regulated by a quorum sensing mechanism (See Box 2, Table 1). Finally, the habitat and lifestyle of an antibiotic producer may influence the target specificity of antibiotics produced. As discussed further in Box 3, a generalist species occupying a broad spectrum of environments would be more likely to benefit from producing broad spectrum antimicrobials or a cocktail of toxins targeting different potential competitors, while those organisms highly specialized for a given habitat may produce antimicrobials with a narrower range, targeting specific competitors.

Box 1. Antimicrobials: Aggression or diplomacy?

The ecological role of compounds that are currently defined as antimicrobials, a subset of secondary metabolites, has recently been the subject of some controversy. After examining the transcriptional response of sensitive bacteria to sub-inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials, several investigators have proposed that the true function of these molecules in nature is to act as signal molecules within and between species 83-85. More recently, it has been suggested that, while the definition of signaling is too stringent to include most antimicrobials and other secondary metabolites, these molecules might act as cues or chemical manipulators as well as serving other functions such as altering central metabolic pathways, contributing to nutrient scavenging or participating in developmental pathways 86-89. For example, diverse small molecules that cause potassium leakage, some of which are antimicrobial, have recently been shown to also stimulate biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis via the up-regulation of extracellular matrix components 90. Similarly, redox-active small antimicrobials, including the phenazine pyocyanin, which is produced by P. aeruginosa, have also been shown to influence gene expression in several bacterial species 91. These findings raise an important issue for microbiologists. When we discover a process in one context, such as the inhibition of bacterial growth at high antibiotic concentration and in laboratory culture, this may not be the context in which this process functions in nature. Certainly, these two activities are not mutually exclusive, and each might benefit the bacteria producing these compounds, under different circumstances.

Table 1.

Examples of quorum sensing regulated antibiotic production

| Group of organisms |

Signal type | Examples: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Antimicrobial(s) | References | ||

| Proteobacteria | Acyl-HSLs |

Pseudomonas choloraphis 30-84 |

phenazines | 98, 99 |

|

Erwinia

cartovora |

carbapenems | 100 | ||

| P. aeruginosa | Pyocyanin, hydrogen cyanide, rhamnolipid |

101-103 | ||

|

Burkholderia

thailandesis |

unidentified | 104 | ||

| Actinomycetes | Butyrolactones, butanolides, furans |

Streptomyces

griseus |

streptomycin | 105 |

| S. coelicolor | methylenomycin | 106 | ||

|

Kitasatospora

setae |

bafilomycin | 107 | ||

| Firmicutes | peptides |

Streptococcus

thermophilus |

antimicrobial peptides |

108 |

|

Lactococcus

lactis |

nisin* | 109 | ||

|

Bacillus

subtilis |

subtilin* | 110 | ||

Some antimicrobial peptides produced by Gram positive bacteria, including nisin and subtilin, also serve as autoregulatory signals at sub-inhibitory concentrations.

Box 3. Pick your poison.

The target specificity of antimicrobials produced by different bacterial species varies widely, from highly specific compounds that only target other strains of the same species, to generally toxic compounds that are inhibitory to a diverse range of species. The target specificity of the compounds a particular organism will synthesize often correlates with the range of habitats and diversity of other species this organism is likely to encounter. For example, Streptomyces spp. commonly inhabit soil, one of the most microbially diverse environments on earth 92. Collectively, Streptomyces spp. produce a stunning array of antimicrobial polyketides and non-ribosomally synthesized peptides. Individual species of Streptomyces have also been shown to synthesize multiple antimicrobial compounds, and genome sequence analysis indicates the potential for the synthesis of even more putative antimicrobial compounds that have yet to be detected under laboratory culture conditions 93. At the other extreme, the biocontrol organism Agrobacterium radiobacter K84 produces the antibiotic agrocin 84 that is highly specific to a subset of plant pathogenic Agrobacterium tumefaciens. This compound mimics the opines agrocinopine A and B, customized nutrient sources produced by plant tissue that is infected by certain A. tumefaciens strains 94, 95. In susceptible A. tumefaciens, the toxin is imported and processed into its toxic form using the same machinery as that used for nutrients 94, 95, while A. radiobacter K84 encodes a factor conferring self-immunity to the toxin 94. Thus, A. radiobacter K84 uses a narrowly targeted antimicrobial to enable it to parasitize the highly specialized opine nutrient source. Representing an intermediate level of specificity between these extremes are organisms which produce bacteriocins, a large group of ribosomally encoded antimicrobial peptides that generally mediate competition between strains of the same species or between closely related species (although broad-spectrum bacteriocins have also been described) 96. For example, in the context of cheese fermentation, which represents a habitat of intermediate diversity compared to soil and A. tumefaciens –induced plant tumors, bacteriocin production by commercially important Lactococcus lactis strains has been linked to their ability to outcompete wild L. lactis species that can contaminate the fermentation process and negatively affect cheese quality 97.

Jamming the Radar

Many of the competitive determinants described above are regulated by quorum sensing (see Box 2 and Table 1). One possible strategy by which bacterial species could avoid succumbing to competition would be to disrupt the signaling of competing species. To date, no experiments have conclusively demonstrated a link between microbial disruption of quorum sensing and the ability to gain a competitive advantage. However, extensive work has demonstrated that enzymes and other compounds produced and secreted by bacteria can interfere with quorum sensing. Quorum sensing using acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as signal molecules, a common strategy employed by diverse proteobacteria, can be disrupted by using at least three bacterially produced enzymatic classes, lactonases, acylases and oxidoreductases 65, 66. These degradative enzymes appear to be prevalent in diverse soils and have been detected in termite hindguts at levels sufficient to significantly impact signaling processes; synthetic signal added to samples from these environments is rapidly degraded, an effect which was verified to be lost in one of the soil types upon autoclaving 67. Some bacteria, such as Variovorax paradoxus, internalize and degrade AHLs, using the breakdown products as carbon and nitrogen sources 68. The prevalence of signal-degrading mechanisms in other environments such as freshwater or marine habitats has not been addressed

Antagonism of signaling is also employed for other types of quorum sensing. The AI-2 quorum sensing signals are produced by a variety of bacterial species. Enteric bacteria including E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium can both produce and consume AI-2; production of the signal uptake is itself regulated by AI-2 levels 69-71. Accordingly, coculture of either Vibrio harveyi or V. cholerae with E. coli leads to disregulation of AI-2-controled functions in these organisms, including their early activation when AI-2 is being produced by E. coli and blocking of signaling when AI-2 is being internalized by E.coli 72. It is unclear what role disruption of AI-2 signaling may play in competition between these species.

In Gram-positive organisms, the primary mechanism of quorum sensing is through short, ribosomally produced, post-translationally modified signal peptides 73. For example, strains of the human pathogen S. aureus regulate expression of their virulence determinants using thiolactone-based auto-inducing peptides (AIPs) 74. The species S. aureus can be divided into four groups based on the sequence of these peptides, and it has been found that peptides of one class are inhibitory to the sensing abilities of the other classes, making this a clear case of within species quorum sensing inhibition 74-76. Peptide-based signaling can also be disrupted by signal degradation. For example, Streptococcus gordonii has been shown to degrade the signal peptide produced by S. mutans species (know as CSP) 77. This may mediate competition between the two species in the human oral cavity, where both species reside, because CSP controls the production of a bacteriocin inhibitory to S. gordonii 77.

Concluding Remarks

The ecology of competition is an old subject, developed through the efforts of numerous macrobiologists. Most of the key principles of competition theory arose through the observational data generated by field ecologists directly studying environmental systems. A limitation of these studies, however, is the difficulty in linking competitive behavior or processes to underlying genetic determinants. This is where bacteria present a wonderful opportunity. Their rapid generation time, genetic malleability and ability to engage in group behaviors make them excellent candidates to test some of the basic theories thought to underpin competition, and to examine how group level processes influence competition between species. For example, experiments with microbial populations have already helped refine and validate several predictions regarding the conditions that favor the maintenance of cooperation in the face of the potential for social cheating 27, 28, 35. The use of many active interference mechanisms of competition by bacterial species should provide particularly useful experimental systems for testing emerging theories regarding the conditions that favor interference over exploitative competition strategies 78. Finally, studies of microbial competition in the context of group level processes may also generate insight into the evolutionary transition to multicellularity, which was undoubtedly driven by competition.

One limitation of many studies of microbial competition conducted to date has been that predictions generated from in vitro studies have not been tested in more natural settings. The emergence of technologies such as high-throughput genomic sequencing, expression profiling, and sophisticated microscopy are now allowing us to ask questions regarding microbial distribution and physiology in complex systems that would not have been possible in the past, and which should facilitate testing of many of these predictions. Incorporation of additional complexity to mimic more natural settings will also enable comparisons between the competitive strategies favored in different settings. For example, antimicrobial production may be more important in densely colonized, nutrient-rich enviroments such as the human oral cavity 79, while motility could be particularly important in an oligotrophic environment like the open ocean 80, 81

The future is bright as microbiologists begin to test ecological theory 82. Undoubtedly, their findings will not only support or refute different principles, but will open up new avenues of thinking about competition and the variables that affect it. These findings not only will inform macrobiological ecology, but will also be crucial in elucidating the dynamics of infectious disease, the establishment and function of microbial communities, and the decline of microbial lineages. This understanding will also promote identification of the key parameters and relationships that generate complex systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lucas Hoffman, E. Peter Greenberg, Greg Velicer, and Thomas Platt for helpful comments which improved the manuscript. Research in the Fuqua lab is supported by the NIH (GM080546) and NSF (MCB-0703467 and DEB-0326842). M.E.H. was a trainee on the IU Genetics, Cellular and Molecular Sciences Training Grant (GM007757). Parsek lab research is supported byNSF (MCB0822405), NIH (R01 AI061396) and (1R01AI077628-01A1), and CFF (CFR565-CR07), and S.B.P. is supported by a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Glossary

- Bacteriocins

Proteinaceous toxins produced by bacteria with antimicrobial toxicity. Most bacteriocins target other strains of the same species as the producing organism, but some are more broad-spectrum

- Co-evolution

The process of two or more species contributing to the selective pressures leading to adaptation of the interacting species

- Colicins

A particular group of bacteriocins produced by and toxic to some strains of E. coli and other enteric bacteria. Colicin producing strains are immune to the colicin they produce as a result of production of an immunity protein

- Competitive exclusion

When competition between species results in the elimination of one species from a given habitat or region

- Contest competition (Interference)

Competition in which one competitor actively harms the other, such as by fighting or production of toxins

- Kin selection

Accumulation of behaviors that may be detrimental to the fitness of the individual which performs them, but that favor the survival of close relatives likely to harbor similar (or identical, as in the case of a clonal bacterial population) alleles conferring the cooperative traits

- Niche

The set of environmental parameters defining the extent of a species habitat

- Negative frequency-dependent selection

Selection favoring individuals only when they are rare in a population

- Public goods

In evolutionary biology, this refers to any resource produced by one individual which is then available for exploitation by other individuals. An example would be extracellular proteases secreted by a bacterium

- Resource ratio model of competition

Elaborated and championed by Tilman, this theory predicts the relationship between species’ ability to use resources, resource availability, and the outcome of competitive interactions. If a single resource is limiting, the model predicts that the species requiring the lowest amount of the resource to continue to grow will outcompete other species having higher requirements for the limiting resource. If multiple resources are limiting, species may face tradeoffs in their ability to exploit different resources at low levels and thus the ratio of the different limiting resources available will determine competitive outcomes

- Scramble competition (Exploitation)

Competition in which one competitor deprives another of a resource (such as a nutrient or habitable space) by depleting that resource

- Social cheaters

Individuals in a population that derive benefit from cooperative behavior by other individuals without themselves contributing to cooperation

References

- 1.Schluter D. Ecological causes of adaptive radiation. Am. Nat. 1996;148:S40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connell JH. The influence of interspecific competition and other factors on the distribution of the barnacle Chthamalus stellatus. Ecology. 1961;42:710–723. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sogin ML, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:12115–12120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusch DB, et al. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monod J. The growth of bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1949;3:371–394. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monod J. La technique de culture continue theorie et applications. Annales De L Institut Pasteur. 1950;79:390–410. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilman D. Resource competition between planktonic algae - experimental and theoretical approach. Ecology. 1977;58:338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tilman D. The resource-ratio hypothesis of plant succession. Am. Nat. 1985;125:827–852. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray MG, Baird DR. Resource-ratio theory applied to large herbivores. Ecology. 2008;89:1445–1456. doi: 10.1890/07-0345.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith V. Effects of resource supplies on the structure and function of microbial communities. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:99–106. doi: 10.1023/a:1020533727307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherif M, Loreau M. Stoichiometric constraints on resource use, competitive interactions, and elemental cycling in microbial decomposers. Am. Nat. 2007;169:709–724. doi: 10.1086/516844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassen R, Llewellyn M, Rainey PB. Ecological constraints on diversification in a model adaptive radiation. Nature. 2004;431:984–988. doi: 10.1038/nature02923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Singh PK. Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:16630–16635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407460101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirisits MJ, Prost L, Starkey M, Parsek MR. Characterization of colony morphology variants isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4809–4821. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4809-4821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rainey PB, Travisano M. Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment. Nature. 1998;394:69–72. doi: 10.1038/27900. The authors demonstrate that providing P. fluorescens with ecological opportunity (growth in spatially structured, static liquid cultures) results in predictable diversification.

- 16.Czárán TL, Hoekstra RF, Pagie L. Chemical warfare between microbes promotes biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:786–790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012399899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr B, Riley MA, Feldman MW, Bohannan BJ. Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock-paper-scissors. Nature. 2002;418:171–174. doi: 10.1038/nature00823. Using a model system with colicin producing, sensitive and resistant E. coli, the authors elegantly demonstrate the ability of this combination of strains to establish an non-transitive competitive network, as predicted by a model they elaborate, and they illustrate the importance of spatial structure in establishing and maintaining the network.

- 18.Reichenbach T, Mobilia M, Frey E. Mobility promotes and jeopardizes biodiversity in rock-paper-scissors games. Nature. 2007;448:1046–1049. doi: 10.1038/nature06095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narisawa N, Haruta S, Arai H, Ishii M, Igarashi Y. Coexistence of antibiotic-producing and antibiotic-sensitive bacteria in biofilms is mediated by resistant bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:3887–3894. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02497-07. Demonstrates the ability of three species isolated from the same sediment to establish an non-transitive competitive network sharing many features of the model network described in 17.

- 20.Coleman ML, Chisholm SW. Code and context: Prochlorococcus as a model for cross-scale biology. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Fernandez JM, de Marsac NT, Diez J. Streamlined regulation and gene loss as adaptive mechanisms in Prochlorococcus for optimized nitrogen utilization in oligotrophic environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:630–638. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.630-638.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan MB, Waterbury JB, Chisholm SW. Cyanophages infecting the oceanic cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. Nature. 2003;424:1047–1051. doi: 10.1038/nature01929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman ML, et al. Genomic islands and the ecology and evolution of Prochlorococcus. Science. 2006;311:1768–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1122050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hense BA, et al. Does efficiency sensing unify diffusion and quorum sensing? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:230–239. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West SA, Diggle SP, Buckling A, Gardner A, Griffin AS. The social lives of microbes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007;38:53–77. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velicer GJ. Social strife in the microbial world. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:330–337. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandoz KM, Mitzimberg SM, Schuster M. Social cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:15876–15881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705653104. With 28, this study delineates conditions under which social cheaters of P. aeruginosa (mutants that no longer respond to a quorum sensing signal) accumulate.

- 28.Diggle SP, Griffin AS, Campbell GS, West SA. Cooperation and conflict in quorum-sensing bacterial populations. Nature. 2007;450:411–U7. doi: 10.1038/nature06279. With 27, this study delineates conditions under which social cheaters of P. aeruginosa (mutants that no longer respond to a quorum sensing signal) accumulate.

- 29.Rainey PB, Rainey K. Evolution of cooperation and conflict in experimental bacterial populations. Nature. 2003;425:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith EE, et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. Documents the accumulation of mutations in P. aeruginosa populations living in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, including finding a relative high rate of mutation in the gene encoding the quorum sensing regulator lasR.

- 31.DArgenio DA, et al. Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;64:512–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platt TG, Bever JD. Kin competition and the evolution of cooperation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Travisano M, Velicer GJ. Strategies of microbial cheater control. Trends in Microbiology. 2004;12:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiegna F, Velicer GJ. Competitive fates of bacterial social parasites: persistence and self-induced extinction of Myxococcus xanthus cheaters. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2003;270:1527–1534. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffin AS, West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation and competition in pathogenic bacteria. Nature. 2004;430:1024–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen SK, Rainey PB, Haagensen JA, Molin S. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature. 2007;445:533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature05514. Describes the interaction of two nutritionally dependent bacteria, and the short term development of mechanisms to enhance their physical association.

- 38.Christensen BB, Haagensen JAJ, Heydorn A, Molin S. Metabolic commensalism and competition in a two-species microbial consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:2495–2502. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2495-2502.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong H, et al. Streptococcus oligofermentans inhibits Streptococcus mutans through conversion of lactic acid into inhibitory H2O2: a possible counteroffensive strategy for interspecies competition. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:872–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05546.x. This paper depicts a particularly intriguing competitive interaction that may have resulted from coevolution between two species living in the human oral cavity.

- 40.Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 1986;50:353–380. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicholson AJ. An outline of the dynamics of animal populations. Aust. J. Zool. 1954;2:9–65. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson EO. Sociomicrobiology: The New Synthesis. The Belknap Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oehmen A, et al. Advances in enhanced biological phosphorus removal: from micro to macro scale. Water Res. 2007;41:2271–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. Bacterial iron sources: From siderophores to hemophores. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;58:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan A, et al. Differential cross-utilization of heterologous siderophores by nodule bacteria of Cajanus cajan and its possible role in growth under iron-limited conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2006;34:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joshi F, Archana G, Desai A. Siderophore cross-utilization amongst rhizospheric bacteria and the role of their differential affinities for Fe3+ on growth stimulation under iron-limited conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2006;53:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver VB, Kolter R. Burkholderia spp. alter Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology through iron sequestration. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2376–2384. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2376-2384.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation, virulence and siderophore production in bacterial parasites. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2003;270:37–44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrison F, Paul J, Massey RC, Buckling A. Interspecific competition and siderophore-mediated cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J. 2008;2:49–55. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.96. One of the few studies that seeks to integrate research on the requirements for maintaining intraspecies cooperation with the pressure imposed by competition from another species.

- 50.Mashburn LM, Jett AM, Akins DR, Whiteley M. Staphylococcus aureus serves as an iron source for Pseudomonas aeruginosa during in vivo coculture. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:554–566. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.554-566.2005. This study uses expression analysis to examine the antagonistic behavior of P. aeruginosa, killing S. aureus to access its iron in a rat peritoneal cavity: a true example of a rumble in the microbial jungle.

- 51.Rickard AH, Gilbert P, High NJ, Kolenbrander PE, Handley PS. Bacterial coaggregation: an integral process in the development of multi-species biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irie Y, O’Toole GA, Yuk MH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipids disperse Bordetella bronchiseptica biofilms. Fems Microbiology Letters. 2005;250:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davies DG, Marques CN. A fatty acid messenger is responsible for inducing dispersion in microbial biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/JB.01214-08. This paper presents the identification and characterization of specific fatty acid produced by P. aeruginosa that, at nM concentrations, stimulates dispersal of biofilms of a number of other microbial species.

- 54.Golowczyc MA, Mobili P, Garrote GL, Abraham AG, De Antoni GL. Protective action of Lactobacillus kefir carrying S-layer protein against Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;118:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson-Henry KC, Hagen KE, Gordonpour M, Tompkins TA, Sherman PM. Surface-layer protein extracts from Lactobacillus helveticus inhibit enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 : H7 adhesion to epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:356–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horie M, et al. Inhibition of the adherence of Escherichia coli strains to basement membrane by Lactobacillus crispatus expressing an S-layer. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;92:396–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xavier JB, Foster KR. Cooperation and conflict in microbial biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:876–881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607651104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.An DD, Danhorn T, Fuqua C, Parsek MR. Quorum sensing and motility mediate interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens in biofilm cocultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:3828–3833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511323103. This study identified quorum sensing as an important mechanism controlling the interaction of two bacterial species in several different cultivation formats, dictating the relative competitive advantage of each microbe.

- 59.Klausen M, Aaes-Jorgensen A, Molin S, Tolker-Nielsen T. Involvement of bacterial migration in the development of complex multicellular structures in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:61–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flannagan RS, Valvano MA, Koval SF. Downregulation of the motA gene delays the escape of the obligate predator Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus 109J from bdelloplasts of bacterial prey cells. Microbiology. 2004;150:649–656. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pham VD, Shebelut CW, Diodati ME, Bull CT, Singer M. Mutations affecting predation ability of the soil bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. Microbiology. 2005;151:1865–1874. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verstraeten N, et al. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McBride MJ. Bacterial gliding motility: multiple mechanisms for cell movement over surfaces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:49–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chao L, Levin BR. Structured habitats and the evolution of anticompetitor toxins in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78:6324–6328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uroz S, et al. N-acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing molecules are modified and degraded by Rhodococcus erythropolis W2 by both amidolytic and novel oxidoreductase activities. Microbiology. 2005;151:3313–3322. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong YH, Wang LH, Zhang LH. Quorum-quenching microbial infections: mechanisms and implications. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2007;362:1201–1211. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang YJ, Leadbetter JR. Rapid acyl-homoserine lactone quorum signal biodegradation in diverse soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:1291–1299. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1291-1299.2005. The authors provide a first glimpse at the prevalence and potential importance of biologically-mediated degradation of acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules in the environment.

- 68.Leadbetter JR, Greenberg EP. Metabolism of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by Variovorax paradoxus. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6921–6926. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6921-6926.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taga ME, Semmelhack JL, Bassler BL. The LuxS-dependent autoinducer Al-2 controls the expression of an ABC transporter that functions in Al-2 uptake in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:777–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taga ME, Bassler BL. Chemical communication among bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:14549–14554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934514100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taga ME. Bacterial signal destruction. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007;2:89–92. doi: 10.1021/cb7000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xavier KB, Bassler BL. Interference with Al-2-mediated bacterial cell-cell communication. Nature. 2005;437:750–753. doi: 10.1038/nature03960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lyon GJ, Novick RP. Peptide signaling in Staphylococcus aureus and other Gram-positive bacteria. Peptides. 2004;25:1389–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ji GY, Beavis R, Novick RP. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science. 1997;276:2027–2030. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarraud S, et al. Exfoliatin-producing strains define a fourth agr specificity group in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6517–6522. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6517-6522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geisinger E, George EA, Muir TW, Novick RP. Identification of ligand specificity determinants in AgrC, the Staphylococcus aureus quorum-sensing receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:8930–8938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710227200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang BY, Kuramitsu HK. Interactions between oral bacteria: inhibition of Streptococcus mutans bacteriocin production by Streptococcus gordonii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:354–362. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.1.354-362.2005. Evidence to support a role for signal degradation in mediating competition between Gram-positive residents of the human oral cavity.

- 78.Amarasekare P. Interference competition and species coexistence. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2002;269:2541–2550. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuramitsu HK, He X, Lux R, Anderson MH, Shi W. Interspecies interactions within oral microbial communities. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:653–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simu K, Hagstrom A. Oligotrophic bacterioplankton with a novel single-cell life strategy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:2445–2451. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2445-2451.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stocker R, Seymour JR, Samadani A, Hunt DE, Polz MF. Rapid chemotactic response enables marine bacteria to exploit ephemeral microscale nutrient patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:4209–4214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709765105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prosser JI, et al. The role of ecological theory in microbial ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:384–392. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yim G, Wang HMH, Davies J. Antibiotics as signalling molecules. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2007;362:1195–1200. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goh EB, et al. Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:17025–17030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252607699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davies J, Spiegelman GB, Yim G. The world of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shank EA, Kolter R. New developments in microbial interspecies signaling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hoffman LR, D’Argenio DA, Bader M, Miller SI. Microbial recognition of antibiotics: ecological, physiological, and therapeutic implications. Microbe. 2007;2:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Keller L, Surette MG. Communication in bacteria: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:249–258. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LEP, Newman DK. Rethinking ‘secondary’ metabolism: physiological roles for phenazine antibiotics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nchembio764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.López D, Fischbach MA, Chu F, Losick R, Kolter R. Structurally diverse natural products that cause potassium leakage trigger multicellularity in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:280–285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810940106. A variety of small molecules, many of them previously characterized for their antimicrobial activity, are shown to signal B. subtilis biofilm development, through a mechanism that involves triggering potassium leakage, that is in turn sensed by a particular membrane protein kinase.

- 91.Dietrich LEP, Teal TK, Price-Whelan A, Newman DK. Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science. 2008;321:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1160619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Toward a census of bacteria in soil. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Challis GL, Hopwood DA. Synergy and contingency as driving forces for the evolution of multiple secondary metabolite production by Streptomyces species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100(Suppl 2):14555–14561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934677100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reader JS, et al. Major biocontrol of plant tumors targets tRNA synthetase. Science. 2005;309:1533–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1116841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim JG, et al. Bases of biocontrol: Sequence predicts synthesis and mode of action of agrocin 84, the Trojan Horse antibiotic that controls crown gall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:8846–8851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ryan M, Rea M, Hill C, Ross R. An application in cheddar cheese manufacture for a strain of Lactococcus lactis producing a novel broad-spectrum bacteriocin, lacticin 3147. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:612–619. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.612-619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pierson LS, 3rd, Keppenne VD, Wood DW. Phenazine antibiotic biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84 is regulated by PhzR in response to cell density. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:3966–3974. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3966-3974.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wood DW, Pierson LS., 3rd The phzI gene of Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84 is responsible for the production of a diffusible signal required for phenazine antibiotic production. Gene. 1996;168:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barnard AM, et al. Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2007;362:1165–1183. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pessi G, Haas D. Transcriptional control of the hydrogen cyanide biosynthetic genes hcnABC by the anaerobic regulator ANR and the quorum-sensing regulators LasR and RhlR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6940–6949. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6940-6949.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ochsner UA, Reiser J. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brint JM, Ohman DE. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Duerkop BA, et al. Quorum-sensing control of antibiotic synthesis in Burkholderia thailandensis. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:3909–18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Horinouchi S. A microbial hormone, A-factor, as a master switch for morphological differentiation and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces griseus. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d2045–57. doi: 10.2741/A897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Corre C, Song L, O’Rourke S, Chater KF, Challis GL. 2-Alkyl-4-hydroxymethylfuran-3-carboxylic acids, antibiotic production inducers discovered by Streptomyces coelicolor genome mining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:17510–17515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805530105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Choi S, Lee C, Hwang Y, Kinoshita H, Nihira T. Cloning and functional analysis by gene disruption of a gene encoding a gamma-butyrolactone autoregulator receptor from Kitasatospora setae. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3423–3430. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3423-3430.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fontaine L, et al. Quorum-sensing regulation of the production of blp bacteriocins in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. of Bacteriol. 2007;189:7195–7205. doi: 10.1128/JB.00966-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuipers OP, Beerthuyzen MM, de Ruyter PG, Luesink EJ, de Vos WM. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27299–27304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stein T, et al. Dual control of subtilin biosynthesis and immunity in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:403–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]