Abstract

Background and objectives: Fluid overload in hemodialysis patients sometimes requires emergent dialysis, but the magnitude of this care has not been characterized. This study aimed to estimate the magnitude of fluid overload treatment episodes for the Medicare hemodialysis population in hospital settings, including emergency departments.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Point-prevalent hemodialysis patients were identified from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Renal Management Information System and Standard Analytical Files. Fluid overload treatment episodes were defined by claims for care in inpatient, hospital observation, or emergency department settings with primary discharge diagnoses of fluid overload, heart failure, or pulmonary edema, and dialysis performed on the day of or after admission. Exclusion criteria included stays >5 days. Cost was defined as total Medicare allowable costs for identified episodes. Associations between patient characteristics and episode occurrence and cost were analyzed.

Results: For 25,291 patients (14.3%), 41,699 care episodes occurred over a mean follow-up time of 2 years: 86% inpatient, 9% emergency department, and 5% hospital observation. Heart failure was the primary diagnosis in 83% of episodes, fluid overload in 11%, and pulmonary edema in 6%. Characteristics associated with more frequent events included age <45 years, female sex, African-American race, causes of ESRD other than diabetes, dialysis duration of 1 to 3 years, fewer dialysis sessions per week at baseline, hospitalizations during baseline, and most comorbid conditions. Average cost was $6,372 per episode; total costs were approximately $266 million.

Conclusions: Among U.S. hemodialysis patients, fluid overload treatment is common and expensive. Further study is necessary to identify prevention opportunities.

Managing fluid status of dialysis patients remains a challenge (1–3). Because dialysis patients are usually oliguric or anuric, their tendency to accumulate fluid must be managed through a combination of limiting salt and fluid intake and ultrafiltration during dialysis sessions. Achieving a balance between avoiding hypovolemia during dialysis and developing fluid overload between dialysis sessions is complicated by patient adherence (4), challenges in assessing fluid status (2,5), and limitations on the length of dialysis sessions (1). Reports suggest that fluid overload is relatively common in dialysis patients (6,7) and is associated with adverse outcomes including hypertension (3,8), exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF) (9), and increased risk of death (7,10).

Although it is well known that fluid overload sometimes results in need for emergent dialysis outside of regularly scheduled dialysis sessions, the magnitude of this care has not been characterized. Emergent fluid overload treatment can occur in dialysis centers or in inpatient and emergency department settings, where the costs are likely to be higher. We developed an algorithm to estimate the magnitude of fluid overload treatment episodes in inpatient, hospital observation, and emergency department settings for the Medicare hemodialysis population, focusing on episodes that might be preventable.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study includes all U.S. ESRD patients who were receiving hemodialysis with Medicare as the primary payer and who survived at least 90 days after ESRD onset on January 1, 2004. Patients who died, changed to peritoneal dialysis, underwent kidney transplant, lost Medicare primary payer status, obtained health maintenance organization (HMO) coverage, recovered renal function, or were lost to follow-up from January 1 to June 30, 2004 were excluded. This 6-month period was used as the baseline definition period. Patients were followed from July 1, 2004 to the earliest of death, modality change (from hemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis), transplant, loss of Medicare coverage (Medicare no longer primary payer), HMO coverage, recovery of renal function, loss to follow-up, or December 31, 2006.

Data and Patient Baseline Information

Data used for this study came from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) Renal Management Information System (REMIS) and CMS Standard Analytical Files. The REMIS database includes information from the CMS Medicare Enrollment Database, the United Network for Organ Sharing transplant database, the ESRD Medical Evidence Report (form CMS-2728), and the ESRD Death Notification (form CMS-2746). The Standard Analytical Files include Medicare Part A institutional claims (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing, home health, and hospice) and Part B physician/supplier claims.

Patient baseline information included demographic characteristics, renal history, hospital days and dialysis frequency in the baseline period, and comorbid conditions. Demographic characteristics, primary cause of ESRD, and dialysis initiation date were obtained from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report. Length of hospital stays in the baseline period was obtained from Part A inpatient claims, and dialysis frequency in the baseline period was obtained from Part A outpatient claims. Age was determined as of January 1, 2004. Dialysis duration was calculated as January 1, 2004 minus first dialysis date. Number of dialysis sessions per month at baseline was defined by the total number of dialysis sessions in the baseline period divided by 6 months minus hospitalization days.

Comorbid conditions were characterized from Medicare Part A and Part B claims in the baseline period, using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and Physicians' Current Procedural Terminology codes (see Appendix 1 for specific codes). A condition was considered present if a code for it appeared on one or more Part A institutional claims (inpatient, skilled nursing facility, or home health agency) or two or more Part A outpatient or Part B physician/supplier claims during the baseline period. Conditions characterized were atherosclerotic heart disease, CHF, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, other cardiac vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, liver disease, dysrhythmia, cancer, diabetes, and dementia.

Outcomes

Fluid Overload Treatment Episodes

Inclusion criteria for fluid overload treatment episodes were as follows: a claim for an episode of care in an inpatient, hospital observation, or emergency department setting with a primary discharge diagnosis of fluid overload, heart failure, or pulmonary edema (see Appendix 2 for the ICD-9-CM codes used) with dialysis performed on the day of admission or on the following day. The care setting was defined by claim type and revenue code: inpatient care by Medicare Part A inpatient claims (including claims for patients admitted to the hospital after first presenting in the emergency department); hospital observation care by Medicare Part A outpatient claims with revenue codes 0760, 0761, 0762, or 0769 (including claims for patients first presenting in the emergency department); and emergency department care by Medicare Part A outpatient claim with revenue code 045x.

A set of exclusions was applied to eliminate cases in which need for emergent fluid overload treatment was precipitated by an acute cardiac event, as indicated by cardiovascular procedures or acute myocardial infarction, vascular access problems, or any medical problem requiring surgical treatment as indentified by a surgical diagnosis-related group (DRG) code (see Appendix 3).

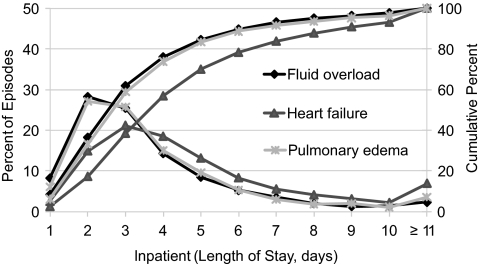

Finally, a length-of-stay (LOS) exclusion was applied, with the rationale that stays for treatment primarily for fluid overload should be relatively short. We plotted the LOS distribution for inpatient episodes that met all criteria except the LOS exclusion (Figure 1). Of episodes with a principle discharge diagnosis of fluid overload, LOS was ≤5 days for 89% and ≤6 days for 93%. With this distribution for patients unambiguously being treated for fluid overload, we chose LOS ≤ 5 days as the primary LOS exclusion criterion. As sensitivity analyses, we also performed all analyses using LOS ≤ 4 days and ≤3 days as exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Distribution of hospital lengths of stay for fluid overload treatment episodes that meet all criteria except the LOS exclusion.

Cost

Cost was defined as total Medicare allowable costs for the identified fluid overload treatment episodes, including Part A inpatient or Part A outpatient costs and Part B costs within the duration of the Part A claims. Part B claims directly indicate Medicare allowable costs. Medicare allowable costs in Part A claims were calculated as the sum of Medicare payments, patient deductibles, coinsurance, and amounts paid by other payers.

Statistical Analyses

Patient characteristics were analyzed for patients who did and did not experience at least one fluid overload treatment episode. Mean, SD, and median were used to describe continuous variables; categorical data were summarized using percentages.

Fluid overload treatment episode counts and rates were described overall by care setting (inpatient, hospital observation, emergency department) and by primary diagnosis. The event rate was defined as the total number of fluid overload treatment episodes divided by total follow-up time minus hospital days. Patients could have multiple events. To study risk factors for fluid overload treatment frequency, an Anderson–Gill model was used to model time to event. Risk factors assessed included age, sex, race, primary ESRD cause, comorbid conditions, dialysis duration, monthly number of dialysis sessions at baseline, and total number of hospitalization days at baseline. Because one patient might have multiple episodes, the robust standard errors of the estimates were calculated using the sandwich method to address correlation among episodes for the same patient. Comorbid conditions, dialysis duration, monthly number of dialysis sessions, and total number of hospitalization days were characterized in a time-varying fashion. Their values were defined during the 6-month baseline period for time to first episode, during the 6 months before the first episode for time to second episode, and so on.

Cost per episode was calculated overall by care setting and by primary diagnosis, reporting mean, median, and 25th and 75th percentiles. A regression model was fit for assessing the relationship between per-person per-year (PPPY) cost of fluid overload treatment episodes, for patients who had at least one, and multiple covariates. The covariates were the same as in the Andersen–Gill model. To improve normality, log transformation of medical cost was used.

Results

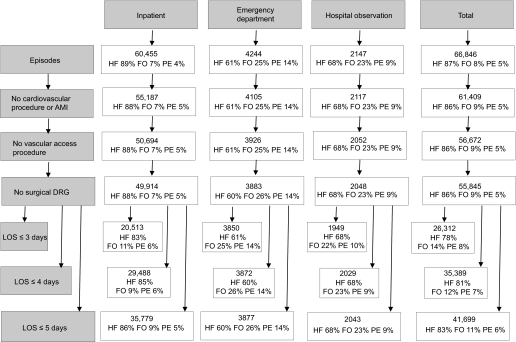

Claims data from 176,790 hemodialysis patients were studied over the 2.5-year follow-up period for appearance of qualifying fluid overload treatment episodes. Mean follow-up for all patients was 2 years. Using the LOS ≤5-day cutoff, 41,699 episodes for 25,291 patients (14.3%) met study criteria; of these, 86% were inpatient, 9% were emergency department, and 5% were hospital observation stays. Episodes with heart failure as the primary diagnosis predominated (83%). Fluid overload was the primary diagnosis for 11% of episodes and pulmonary edema for 6%. Figure 2 presents counts of episodes by care setting and by primary diagnosis as exclusion criteria were sequentially applied. The overall episode rate was 13.7 episodes/100 patient-years. Setting-specific rates were inpatient, 11.8 episodes/100 patient-years; hospital observation, 0.7 episodes/100 patient-years; and emergency department, 1.3 episodes/100 patient-years.

Figure 2.

Counts of fluid overload treatment episodes when exclusion criteria are applied. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; FO, fluid overload; HF, heart failure; PE, pulmonary edema.

Patients who experienced fluid overload treatment episodes were more likely to be women, to be African American, to have hypertension as the primary cause of ESRD, and to have been hospitalized during the baseline period compared with patients who experienced no episodes. Patients who experienced episodes were also more likely to have each comorbid condition studied except cancer and dementia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics (n = 176,790)a

| Characteristics | Fluid Overload Treatment Episode Defined by Length of Hospital Stay |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Days |

≤4 Days |

≤3 Days |

||||

| Event | No Event | Event | No Event | Event | No Event | |

| n | 25,291 | 151,499 | 22,265 | 154,525 | 17,457 | 159,333 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| <45 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.3 | 14.8 |

| 45 to 64 | 38.0 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 38.1 | 39.3 | 38.0 |

| 65 to 74 | 26.5 | 24.6 | 26.2 | 24.7 | 25.1 | 24.8 |

| ≥75 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 21.2 | 22.3 | 20.3 | 22.4 |

| Gender | ||||||

| male | 51.0 | 54.1 | 51.4 | 54.0 | 52.3 | 53.8 |

| female | 49.0 | 45.9 | 48.6 | 46.0 | 47.7 | 46.2 |

| Race | ||||||

| white | 50.7 | 52.8 | 50.1 | 52.8 | 49.6 | 52.8 |

| African American | 44.3 | 41.2 | 44.9 | 41.2 | 45.6 | 41.2 |

| other | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 6.0 |

| Primary cause of ESRD | ||||||

| diabetes | 43.1 | 41.9 | 42.6 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 42.1 |

| hypertension | 32.5 | 29.3 | 32.8 | 29.3 | 33.0 | 29.4 |

| GN | 10.6 | 12.2 | 10.8 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 12.1 |

| other | 13.8 | 16.7 | 13.8 | 16.6 | 14.1 | 16.5 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| ASHD | 48.0 | 37.5 | 47.5 | 37.7 | 47.1 | 38.1 |

| CHF | 56.7 | 40.1 | 56.4 | 40.4 | 56.6 | 40.9 |

| CVA/TIA | 16.3 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 15.7 | 15.1 |

| PVD | 32.5 | 29.6 | 32.3 | 29.7 | 31.8 | 29.8 |

| cardiac (other) | 28.3 | 19.8 | 28.2 | 20.0 | 28.3 | 20.2 |

| COPD | 22.2 | 13.9 | 22.2 | 14.1 | 22.2 | 14.3 |

| GI bleeding | 7.5 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 6.3 |

| liver disease | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.6 |

| dysrhythmia | 23.0 | 18.5 | 22.7 | 18.6 | 22.1 | 18.8 |

| cancer | 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 7.7 |

| diabetes | 59.2 | 56.4 | 58.6 | 56.6 | 57.7 | 56.7 |

| dementia | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Baseline hospitalizations, days | ||||||

| 0 | 43.5 | 57.1 | 43.9 | 57.5 | 44.2 | 57.7 |

| 1 to 7 | 29.9 | 21.9 | 29.4 | 21.7 | 28.9 | 21.6 |

| 8 to 14 | 11.5 | 8.8 | 11.6 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 8.6 |

| ≥15 | 15.2 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 12.1 | 15.2 | 12.0 |

| Monthly number of dialysis sessions | ||||||

| mean (SD) | 13.0 (2.5) | 13.0 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.5) | 13.0 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.4) | 13.0 (3.1) |

| median | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| Dialysis duration, years | ||||||

| <1 | 17.9 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 16.6 | 17.8 | 16.6 |

| 1 to <3 | 35.3 | 32.4 | 35.3 | 32.4 | 35.4 | 32.3 |

| 3 to <5 | 21.8 | 21.3 | 22.1 | 21.2 | 22.0 | 21.2 |

| ≥5 | 25.1 | 29.6 | 24.9 | 29.8 | 24.8 | 29.9 |

ASHD, atherosclerotic heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA/TIA, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack; GI, gastrointestinal; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Values are percents, except average monthly number of dialysis sessions.

Table 2 presents associations between patient characteristics and frequency of fluid overload treatment episodes, as indicated by relative density results from the Anderson–Gill model. Characteristics associated with more frequent events included younger age (<45 years), female sex, African-American race, causes of ESRD other than diabetes, dialysis duration 1 to 3 years, smaller average number of dialysis sessions per month at baseline, hospitalizations during baseline, and all comorbid conditions studied except dementia, which was associated with less frequent events.

Table 2.

Associations between patient characteristics and frequency (density) of fluid overload treatment episodes

| Covariates | Fluid Overload Treatment Episode Defined by Length of Hospital Stay |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Days |

≤4 Days |

≤3 Days |

|

| Relative Density (P) | Relative Density (P) | Relative Density (P) | |

| Age, years (reference, 45 to 64 years) | |||

| 0 to 44 | 1.46 (< 0.0001) | 1.54 (< 0.0001) | 1.74 (< 0.0001) |

| 65 to 74 | 1.12 (< 0.0001) | 1.15 (< 0.0001) | 1.22 (< 0.0001) |

| ≥75 | 0.98 (0.2547) | 0.96 (0.0120) | 0.94 (< 0.0001) |

| Gender (reference, male) | |||

| female | 1.06 (< 0.0001) | 1.04 (0.0002) | 1.01 (0.3082) |

| Race (reference, white) | |||

| African American | 1.18 (< 0.0001) | 1.20 (< 0.0001) | 1.19 (< 0.0001) |

| other | 0.99 (0.6480) | 0.98 (0.4945) | 0.95 (0.1177) |

| Primary cause of ESRD (reference, diabetes) | |||

| hypertension | 1.24 (< 0.0001) | 1.26 (< 0.0001) | 1.28 (< 0.0001) |

| GN | 1.11 (< 0.0001) | 1.14 (< 0.0001) | 1.16 (< 0.0001) |

| other | 1.07 (0.0005) | 1.09 (< 0.0001) | 1.12 (< 0.0001) |

| Dialysis duration, years (reference 1 to 3 years) | |||

| <1 | 0.96 (< 0.0001) | 0.95 (< 0.0001) | 0.95 (< 0.0001) |

| 3 to <5 | 0.75 (< 0.0001) | 0.76 (< 0.0001) | 0.77 (< 0.0001) |

| ≥5 | 0.88 (< 0.0001) | 0.89 (< 0.0001) | 0.91 (< 0.0001) |

| Average monthly number of dialysis sessions | 0.85 (< 0.0001) | 0.85 (< 0.0001) | 0.85 (< 0.0001) |

| Hospital days in baseline period (reference, 0 days) | |||

| 1 to 7 | 1.25 (< 0.0001) | 1.27 (< 0.0001) | 1.27 (< 0.0001) |

| 8 to 14 | 1.17 (< 0.0001) | 1.14 (< 0.0001) | 1.06 (0.0053) |

| ≥15 | 1.13 (< 0.0001) | 1.07 (0.0007) | 0.98 (0.475) |

| Comorbid conditions (reference, none) | |||

| ASHD | 1.28 (< 0.0001) | 1.27 (< 0.0001) | 1.26 (< 0.0001) |

| CHF | 2.16 (< 0.0001) | 2.15 (< 0.0001) | 2.19 (< 0.0001) |

| CVA/TIA | 1.23 (< 0.0001) | 1.23 (< 0.0001) | 1.25 (< 0.0001) |

| PVD | 1.19 (< 0.0001) | 1.19 (< 0.0001) | 1.20 (< 0.0001) |

| cardiac (other) | 2.09 (< 0.0001) | 2.12 (< 0.0001) | 2.19 (< 0.0001) |

| COPD | 1.65 (< 0.0001) | 1.66 (< 0.0001) | 1.67 (< 0.0001) |

| GI bleeding | 1.24 (< 0.0001) | 1.25 (< 0.0001) | 1.29 (< 0.0001) |

| liver disease | 1.31 (< 0.0001) | 1.32 (< 0.0001) | 1.33 (< 0.0001) |

| dysrhythmia | 1.24 (< 0.0001) | 1.24 (< 0.0001) | 1.23 (< 0.0001) |

| cancer | 1.14 (< 0.0001) | 1.14 (< 0.0001) | 1.14 (< 0.0001) |

| diabetes | 1.13 (< 0.0001) | 1.13 (< 0.0001) | 1.13 (< 0.0001) |

| dementia | 0.84 (< 0.0001) | 0.81 (< 0.0001) | 0.76 (< 0.0001) |

The average cost was $6,372 per fluid overload treatment episode. As expected, average cost for inpatient episodes ($7,171) was higher than for hospital observation ($1,947) or emergency department ($1,326) episodes. In each care setting, costs were higher for primary diagnoses of heart failure or pulmonary edema than for primary diagnosis of fluid overload (Table 3). Linear regression analysis showed that patient characteristics associated with higher PPPY Medicare allowable costs included older age (≥75 years), hypertension as cause of ESRD, smaller average number of dialysis sessions at baseline, number of days hospitalized during baseline, and all comorbid conditions studied except peripheral vascular disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, and diabetes. Dialysis duration <1 year showed a small association with lower costs. The associations observed were generally modest in strength, with the strongest being older age, hospital days at baseline, CHF, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia (Table 4).

Table 3.

Average cost per fluid overload treatment episode

| Care Setting, Discharge Diagnosis | Cost per Fluid Overload Treatment Episode Defined by Length of Hospital Stay, $ |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Days |

≤4 Days |

≤3 Days |

|||||||

| Mean | Median | 25th, 75th Percentile | Mean | Median | 25th, 75th Percentile | Mean | Median | 25th, 75th Percentile | |

| All | 6372 | 6645 | 5483, 7836 | 6112 | 6467 | 5132, 7653 | 5657 | 6149 | 3729, 7378 |

| heart failure | 6557 | 6742 | 5793, 7836 | 6311 | 6579 | 5589, 7651 | 5872 | 6298 | 4795, 7380 |

| fluid overload | 4408 | 5054 | 1416, 6137 | 4255 | 4938 | 1308, 6016 | 3979 | 4654 | 1168, 5852 |

| pulmonary edema | 7310 | 8069 | 2247, 9516 | 6973 | 7935 | 1946, 9379 | 6490 | 7611 | 1670, 9147 |

| Inpatient | 7171 | 6927 | 6056, 8079 | 7028 | 6803 | 5946, 7939 | 6826 | 6618 | 5762, 7755 |

| heart failure | 7144 | 6930 | 6132, 8003 | 6996 | 6805 | 6021, 7853 | 6775 | 6616 | 5837, 7641 |

| fluid overload | 5961 | 5729 | 5020, 6713 | 5898 | 5665 | 4970, 6611 | 5800 | 5581 | 4862, 6513 |

| pulmonary edema | 9539 | 8781 | 7850, 10,032 | 9344 | 8710 | 7795, 9969 | 9173 | 8619 | 7682, 9934 |

| Hospital observation | 1947 | 1634 | 1170, 2157 | 1942 | 1630 | 1168, 2146 | 1922 | 1614 | 1155, 2118 |

| heart failure | 2135 | 1765 | 1299, 2271 | 2129 | 1757 | 1296, 2262 | 2110 | 1723 | 1273, 2222 |

| fluid overload | 1511 | 1356 | 950, 1859 | 1508 | 1353 | 950, 1846 | 1490 | 1348 | 946, 1827 |

| pulmonary edema | 1654 | 1461 | 1136, 1930 | 1654 | 1461 | 1136, 1930 | 1643 | 1458 | 1092, 1917 |

| Emergency department | 1326 | 1150 | 802, 1570 | 1325 | 1150 | 801, 1569 | 1321 | 1147 | 799, 1565 |

| heart failure | 1445 | 1244 | 896, 1679 | 1443 | 1243 | 896, 1679 | 1442 | 1242 | 896, 1678 |

| fluid overload | 969 | 870 | 607 1209 | 965 | 869 | 607, 1207 | 951 | 864 | 604, 1194 |

| pulmonary edema | 1471 | 1211 | 875, 1729 | 1471 | 1211 | 875, 1729 | 1470 | 1211 | 874, 1730 |

Table 4.

Association between patient characteristics and Medicare costs (PPPY) for fluid overload treatment episodes

| Covariates | Fluid Overload Treatment Episode Defined by Length of Hospital Stay |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Days |

≤4 Days |

≤3 Days |

|

| Relative Cost (P) | Relative Cost (P) | Relative Cost (P) | |

| Age, years (reference, 45 to 64 years) | |||

| 0 to 44 | 0.95 (0.0194) | 0.95 (0.040) | 0.98 (0.4330) |

| 65 to 74 | 0.987 (0.0322) | 0.98 (0.239) | 0.99 (0.626) |

| ≥75 | 1.11 (< 0.0001) | 1.11 (< 0.0001) | 1.08 (0.0007) |

| Gender (reference, men) | |||

| women | 0.99 (0.4922) | 0.99 (0.483) | 0.98 (0.3069) |

| Race (reference, white) | |||

| African American | 1.00 (0.9773) | 1.00 (0.9812) | 0.98 (0.2103) |

| other | 1.04 (0.1200) | 1.05 (0.0785) | 1.06 (0.1137) |

| Primary cause of ESRD (reference, diabetes) | |||

| hypertension | 1.05 (0.0100) | 1.05 (0.0137) | 1.05 (0.0296) |

| GN | 1.01 (0.8176) | 1.01 (0.6854) | 1.03 (0.3286) |

| other | 1.02 (0.3039) | 1.03 (0.2169) | 1.05 (0.0916) |

| Dialysis duration, years (reference, 1 to 3 years) | |||

| <1 | 0.98 (< 0.0001) | 0.98 (< 0.0001) | 0.98 (< 0.0001) |

| 3- to <5 | 0.98 (0.2622) | 0.98 (0.2575) | 0.99 (0.6958) |

| ≥5 | 1.00 (0.8414) | 1.01 (0.6604) | 1.01 (0.5266) |

| Average monthly number of dialysis sessions | 0.96 (0.0155) | 0.96 (0.0292) | 0.96 (0.0631) |

| Hospital days in baseline (reference, 0 days) | |||

| 1 to 7 | 1.10 (< 0.0001) | 1.11 (< 0.0001) | 1.12 (< 0.0001) |

| 8 to 14 | 1.16 (< 0.0001) | 1.17 (< 0.0001) | 1.15 (< 0.0001) |

| ≥15 | 1.23 (< 0.0001) | 1.21 (< 0.0001) | 1.21 (< 0.0001) |

| Comorbid conditions (reference, none) | |||

| ASHD | 1.06 (< 0.0001) | 1.06 (< 0.0001) | 1.05 (0.0032) |

| CHF | 1.18 (< 0.0001) | 1.17 (< 0.0001) | 1.18 (< 0.0001) |

| CVA/TIA | 1.03 (0.0544) | 1.01 (0.6120) | 1.01 (0.6198) |

| PVD | 1.02 (0.1488) | 1.02 (0.2714) | 0.99 (0.4368) |

| cardiac (other) | 1.08 (< 0.0001) | 1.09 (< 0.0001) | 1.08 (< 0.0001) |

| COPD | 1.13 (< 0.0001) | 1.12 (< 0.0001) | 1.10 (< 0.0001) |

| GI bleeding | 0.96 (0.1073) | 0.96 (0.1111) | 0.98 (0.5144) |

| liver disease | 1.08 (0.0005) | 1.07 (0.0022) | 1.10 (0.0007) |

| dysrhythmia | 1.05 (0.0016) | 1.04 (0.0346) | 1.03 (0.1543) |

| cancer | 1.05 (0.0467) | 1.04 (0.0797) | 1.06 (0.0548) |

| diabetes | 0.99 (0.7139) | 0.99 (0.5882) | 0.99 (0.5939) |

| dementia | 1.10 (0.0398) | 1.12 (0.0235) | 1.11 (0.0823) |

Using ≤3 or ≤4 days, rather than ≤5 days, as the LOS cutoff decreased episode counts almost entirely through fewer inpatient episodes. Using LOS ≤ 4 days reduced the total episode count by 15%, from 41,699 to 35,389; using LOS ≤ 3 days reduced the count by 37%, to 26,312 (Figure 2). Compared with average cost per episode of $6,372 using LOS ≤ 5 days, average cost was 4% less ($6,112) using LOS ≤ 4 days and 11% less ($5,657) using LOS ≤ 3 days (Table 3). Although magnitude of the associations varies somewhat, patterns of association between patient characteristics and frequency of events (Table 2) and PPPY cost of events (Table 4) remain the same regardless of which LOS exclusion is used.

Discussion

In a Medicare point-prevalent hemodialysis population, analysis of claims data found treatment of fluid overload in the inpatient, hospital observation, and emergency department settings at a rate of 13.7 episodes/100 patient-years. Total costs for the episodes identified in the study cohort over the 2.5-year follow-up period were approximately $266 million. The estimates produced by our algorithm are admittedly imprecise because of limitations of the claims data. Several aspects of the methodology merit discussion.

First, episodes with primary diagnosis codes for heart failure and pulmonary edema were included, along with episodes with a primary diagnosis code for fluid overload. The relationship between fluid overload and heart failure is complex, with each exacerbating the other (9,11). Details available in Medicare claims data do not allow for clean separation of cases in which fluid overload was the initial condition resulting in exacerbation of heart failure versus cases in which changes in heart function resulted in fluid overload. We attempted to limit cases to those in which fluid overload was primary by using methodology that excluded episodes with codes indicating cardiovascular procedures or acute myocardial infarction. Approximately 10% of all heart failure hospitalizations were eliminated through these exclusions. Despite these exclusions, a decrease in heart function, resulting in fluid overload or pulmonary edema, may have been primary in some of the remaining cases. However, it is also likely that in some of the excluded cases, fluid overload was in fact primary, leading to acute myocardial infarction or the need for cardiovascular procedures.

Vascular access failure prevents dialysis and, in some cases, can result in a patient being admitted to the hospital or seen in an emergency department to re-establish vascular access. On arrival, such patients might well need treatment for fluid overload. Although this is an important issue, we wished to focus on episodes potentially preventable through means other than preservation of vascular access. Excluding cases with codes for vascular access procedures eliminated 8% of episodes remaining after the acute myocardial infarction/cardiovascular procedure exclusion. Excluding episodes with a surgical DRG was meant as a conservative step to exclude cases in which an underlying condition could have led to fluid overload. It eliminated only 1% of cases remaining after the acute myocardial infarction/cardiovascular procedure and vascular access procedure exclusions.

The LOS exclusion was an important final step in producing the cohort of episodes. One might argue that all cases carrying fluid overload as the primary discharge diagnosis should be included. As a conservative measure, we chose to exclude cases at the upper end of LOS distribution for this group and to apply that same LOS cut to episodes with heart failure or pulmonary edema as the primary diagnosis. Use of LOS ≤ 5 days seemed reasonable given our belief that patients admitted for fluid overload treatment would not uncommonly be kept through a second dialysis session to ensure stability. Using LOS ≤4-day or ≤3-day exclusions resulted, unsurprisingly, in an important decrease in counts and total costs of episodes; however, of note, average cost per episode decreased only modestly and associations between patient factors and frequency of episodes or cost of episodes changed little. No matter which LOS exclusion is used, the magnitude of these episodes is large.

Although this study focused on potentially preventable fluid overload treatment, we are unable to define the proportion of these cases that were in fact preventable, much less which individual episodes could have been avoided. More detailed patient information would be needed to make this determination. For example, Medicare claims during the period studied do not give information on the days when dialysis was performed in the period leading up to the fluid overload treatment episode. If available, this information would give insight into missed sessions as a cause. The association of patient factors with episode occurrence does give some hints regarding etiology. The positive association with fewer dialysis sessions at baseline suggests that suboptimal adherence to regular dialysis sessions might play a role. And the age group with highest frequency of episodes is <45 years, consistent with findings in other studies that younger populations are least adherent to regular dialysis sessions and to fluid and dietary restrictions (4,6). The independent associations with measures of morbidity, such as hospitalization during baseline and most comorbid conditions studied, indicate that sicker patients, along with younger patients, are at increased risk. Possibly, different populations are at increased risk for different reasons. Clear delineation of why specific patient groups are at higher risk would point the way toward effective prevention efforts.

Younger patients were at highest risk for event occurrence, and the oldest age category (≥75 years) was associated with higher PPPY costs. This is probably due to higher likelihood of inpatient, versus less expensive hospital observation or emergency department treatment, in the elderly population. Episodes were 89% inpatient for ages ≥75 years, 87% for ages 65 to 74 years, 85% for ages 45 to 64 years, and 82% for ages ≤44 years (using LOS ≤5 days).

Finally, our study was limited to the Medicare population, and its results might not be fully generalizable to the 21% of January 1, 2004 point-prevalent U.S. hemodialysis patients with a primary payer other than Medicare.

This study demonstrates that among U.S. hemodialysis patients, treatment for fluid overload in inpatient, hospital observation, and emergency department settings is relatively common and quite expensive. Further study of this topic using data with more detailed patient information would be useful to confirm the magnitude of treatments reported here and is necessary to understand the scale and nature of prevention opportunities now present.

Disclosures

Dr. Arneson holds an ownership interest in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Gilbertson has received consulting fees from Amgen and AMAG Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Foley has received consulting fees from 21st Services, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, Pursuit Vascular, Fresenius, and Affymax. Dr. Collins has received consulting fees from Amgen, Affymax, NxStage, and Baxter. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research contract from Fresenius Medical Care. The contract provides for the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation investigators to have final determination of manuscript content. The authors thank Chronic Disease Research Group colleagues Shane Nygaard, BA, for manuscript preparation, and Nan Booth, MSW, MPH, for manuscript editing.

Appendices

Appendix 1.

ICD-9-CM codes for comorbid conditions

| Condition | ICD-9-CM Codes |

|

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis Codes | V Codes | |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 410 to 414 | V45.81; V45.82 |

| Congestive heart failure | 398.91; 422; 425; 428; 402.x1; 404.x1; 404.x3 | V42.1 |

| Cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack | 430 to 438 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 440 to 444; 447; 451 to 453; 557 | |

| Cardiac (other) | 420; 421; 423; 424; 429; 785.0 to 785.3 | V42.2;V43.3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 491 to 494; 496; 510 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 456.0 to 456.2; 530.7; 531 to 534; 569.84; 569.85; 578 | |

| Liver disease | 570; 571; 572.1; 572.4; 573.1 to 573.3 | V42.7 |

| Dysrhythmia | 426; 427 | V45.0; V53.3 |

| Cancer | 140 to 172; 174 to 208; 230; 231; 233; 234 | |

| Diabetes | 250; 357.2; 362.0x; 366.41 | |

| Dementia | 290; 3310 | |

Appendix 2.

ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes used to define primary diagnoses

| Primary Diagnosis | ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes |

|---|---|

| Fluid overload | 276.6 |

| Heart failure | 428; 402.x1; 404.x1; 404.x3; 398.91 |

| Pulmonary edema | 518.4; 514 |

Appendix 3.

Codes for cardiovascular procedures, vascular access and complications, and surgical DRG

| ICD-9-CM Codes (any position) |

CPT and Surgical DRG Codes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis Codes | Procedure Codes | ||

| Cardiovascular procedure | |||

| CABG surgery | 36.1x | 33510 to 33523; 33533 to 33536 | |

| PCI | 00.66; 36.01; 36.02; 36.06 | 92980 to 92982; 92984; 92995; 92996 | |

| ICD | 37.94 | ||

| CRT-D | 00.51 | ||

| Coronary angiography and/or catheterization | 37.22 to 37.23; 88.53 to 88.57 | 93508, 93510, 93511, 93524, 93526, 93527, 93529, 93531 to 93533, 93539, 93540, 93543, 93545, 93555 | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 410, 410.x0, 410.x1 | ||

| Vascular access and complicationsa | |||

| Vascular access | 38.95, 39.27, 39.42, 39.43, 39.93, 39.94, 86.07 | 36488,b 36489,b 36490,b 36491,b 36533,b 36555,b 36556,b,36557,b 36558,b 36565,b 36800, 49419, 49420, 49421, 36810, 36818, 36820, 36821, 36825, 36830 | |

| Complication | 996.1, 996.62, 996.73 | 34101,b 35190,b 35321,b 35458,b 35460,b 35475,b 35476,b 35484,b 35875,b 35876,b 35900,b 35903,b 35910,b 36005,b 36145, 36534,b 36535,b 36550,b 36575,b 36580,b 36581,b 36584,b 36589,b 36596,b 36597,b 36831, 36832, 36833,36834,b 36838, 36860, 36861, 36870, 37190,b 37201,b 37205,b 37206,b 37207,b 37208,b 37607, 49422, 75790, 75820,b 75860,b 75896,b 75960,b 75962,b 75978,b 76937, 75998,b 00532,b 01784,b 01844,b 90939, 90940, G0159, M0900 | |

| Surgical DRG codes | 001 to 008, 036 to 042, 049 to 063, 075 to 077, 103 to 120, 567 to 570, 146 to 171,191 to 201, 577 to 579, 209 to 234, 257 to 270, 285 to 293, 303 to 315, 334 to 345, 353 to 365, 392 to 394, 400 to 402, 406 to 408, 439 to 443, 471, 472, 476 to 486, 458, 459, 506, 507, 513 to 520, 525 to 558, 493 to 504, 439, 415, 424, 461, 474, 573, 468, 488, 491 | ||

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillators; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

CPT codes for vascular access and complications are from Medicare Part B claims.

Requires an accompanying renal diagnosis code or V code for inclusion: 250.xx, 403.xx, 580 to 589, 593.xx, 996.1, 996.62, 996.73, V56.x, V45.1.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Charra B: Fluid balance, dry weight, and blood pressure in dialysis. Hemodial Int 11: 21–31, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raimann J, Liu L, Ulloa D, Kotanko P, Levin NW: Consequences of overhydration and the need for dry weight assessment. Contrib Nephrol 161: 99–107, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wabel P, Moissl U, Chamney P, Jirka T, Machek P, Ponce P, Taborsky P, Tetta C, Velasco N, Vlasak J, Zaluska W, Wizemann V: Towards improved cardiovascular management: The necessity of combining blood pressure and fluid overload. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 2965–2971, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leggat JE, Jr, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Golper TA, Jones CA, Held PJ, Port FK: Noncompliance in hemodialysis: Predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 139–145, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishibe S, Peixoto AJ: Methods of assessment of volume status and intercompartmental fluid shifts in hemodialysis patients: Implications in clinical practice. Semin Dial 17: 37–43, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindberg M, Prutz KG, Lindberg P, Wikstrom B: Interdialytic weight gain and ultrafiltration rate in hemodialysis: Lessons about fluid adherence from a national registry of clinical practice. Hemodial Int 13: 181–188, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Van Wyck D, Bunnapradist S, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC: Fluid retention is associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis. Circulation 119: 671–679, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charra B, Chazot C: Volume control, blood pressure and cardiovascular function. Lessons from hemodialysis treatment. Nephron Physiol 93: 94–101, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shotan A, Dacca S, Shochat M, Kazatsker M, Blondheim DS, Meisel S. Fluid overload contributing to heart failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20[Suppl 7]: vii24–vii27, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wizemann V, Wabel P, Chamney P, Zaluska W, Moissl U, Rode C, Malecka-Masalska T, Marcelli D: The mortality risk of overhydration in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1574–1579, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotter G, Felker GM, Adams KF, Milo-Cotter O, O'Connor CM: The pathophysiology of acute heart failure—Is it all about fluid accumulation? Am Heart J 155: 9–18, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]