Abstract

Background and objectives: Increased urinary albumin excretion is a known risk factor for cardiovascular events and clinical nephropathy in patients with diabetes. Whether microalbuminuria predicts long-term development of chronic renal insufficiency (CRI) in patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension remains to be documented.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: We conducted an 11.8-year follow-up of 917 patients who did not have diabetes and had hypertension and were enrolled in the Microalbuminuria: A Genoa Investigation on Complications (MAGIC) cohort between 1993 and 1997. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) was assessed at baseline in untreated patients in a core laboratory. Microalbuminuria was defined as ACR ≥22 mg/g in men and ACR ≥31 mg/g in women.

Results: A total of 10,268 person-years of follow-up revealed that baseline microalbuminuria was associated with an increased risk for developing CRI (relative risk [RR] 7.61; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.19 to 8.16; P < 0.0001), cardiovascular events (composite of fatal and nonfatal cardiac and cerebrovascular events; RR 2.11; 95% CI 1.08 to 4.13; P < 0.028), and cardiorenal events (composite of former end points; RR 3.21; 95% CI 1.86 to 5.53; P < 0.0001). Microalbuminuria remained significantly related to CRI (RR 12.75; 95% CI 3.62 to 44.92; P < 0.0001) and cardiorenal events (RR 2.58; 95% CI 1.32 to 5.05; P = 0.0056) even after adjustment for several baseline covariates.

Conclusions: Microalbuminuria is an independent predictor of renal and cardiovascular complications in patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension.

Renal dysfunction is a common finding in patients with hypertension and is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events (CVEs) (1,2) as well as with progression to ESRD (3). It has been pointed out that cardiovascular risk progressively increases as renal function declines and that it is already significantly elevated at the earliest stages of renal damage (4). Identifying the precursors of overt kidney disease is therefore of utmost importance to limit the burden of cardiovascular and renal morbidity.

Increased urinary albumin excretion (UAE) has been related to unfavorable cardiovascular outcomes in the general population (5,6) and in patients with diabetes and in high-risk patients (7). Furthermore, the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study (8) confirmed the predictive power of microalbuminuria and its changes over time (9) in a large cohort of carefully monitored patients during a 5-year follow-up; however, the renal predictive value of albuminuria is thus far limited to high-risk patients with or without diabetes (10,11) and to the general population (12–14). To understand better the natural history of hypertensive renal disease, especially at an early stage when intervention may prevent or delay sequelae, we sought to examine the role of microalbuminuria as a predictor of overt kidney disease in a cohort of patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

The design and main cross-sectional results of the Microalbuminuria: A Genoa Investigation on Complications (MAGIC) have previously been described (15). In brief, a total of 1230 patients with primary hypertension were recruited between 1993 and 1997 from among those who were attending several outpatient hypertension clinics in the Genoa area (for a list of participating centers, see reference [15]) and were followed up for a median of 11.8 years (range 1.6 to 14.2 years).

Exclusion criteria were age <18 years; evidence of neoplastic, hepatic, and/or renal disease (defined as serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dl in men and >1.4 mg/dl in women or overt proteinuria); chronic heart failure (New York Heart Association classes III and IV); diabetes; severe obesity; severe hypertension; and disabling diseases such as dementia and the inability to cooperate. More than 90% of the remaining patients (n = 1122; 614 men, 508 women) agreed to participate in the study. Diagnosis of primary hypertension was made by the attending physician after complete medical history, physical examination, and routine biochemical analyses of blood and urine had been obtained from the patients.

Hypertension was defined according to the fifth report of Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure criteria as an average BP ≥140/90 mmHg on at least three different occasions or by the presence of antihypertensive treatment. None of the patients showed evidence or history of congestive heart failure, ischemic cardiopathy, or advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Data on the patients (n = 205; 106 men, 99 women) who did not comply with washout instructions (63 patients), failed to collect urine samples properly (67 patients), or had to resume treatment because of severe hypertension during the washout period (61 patients) were excluded from analysis. Nine patients (5 men, 4 women) were excluded because of hypokalemia (serum K <3.5 mmol/L) and five because of macroalbuminuria (ACR >25 mg/mmol in men and >35 mg/ mmol in women in the presence of a normal routine urine examination). Attendance was voluntary, and each participant provided written informed consent. All surveys were approved by the ethics committee of our institution. Data that were obtained from the remaining 917 patients (514 men, 403 women; all white) form the basis of this report.

Baseline Measures

During the baseline visit with the clinical research staff, patients reported family history and lifestyle habits. The research staff measured height, weight, and BP using standard procedures. None of the patients were on medication at the time of the study. They either had never been treated for hypertension (n = 725 [79%]) or had been taken off therapy at least 4 weeks before the study (n = 192 [21%]). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the following formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2. Ideal body weight was calculated by the Lorentz formula (16).

Blood and Urine Sampling Procedures and Biochemical Assays

At the end of the washout period, if any, on the study day, venous blood was drawn after an overnight fast in preparation for laboratory examinations, and albuminuria was evaluated by measuring the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). The mean of three nonconsecutive first morning samples was recorded. Only samples from patients with negative urine cultures were collected. The urine albumin concentration was measured using a commercially available RIA kit (Pantec, Torino, Italy) in a core laboratory. Microalbuminuria was defined as an ACR of ≥22 mg/g in men and ≥31 mg/g in women. Creatinine clearance was estimated (estimated GFR [eGFR]) using the Cockcroft-Gault formula (17). Ideal body weight was used in the formula.

End Points

The primary end points were the development of chronic renal insufficiency (CRI), a composite of fatal and nonfatal cerebrovascular events and cardiovascular events (CVEs), and a composite of CVEs and CRIs (i.e., cardiorenal events [CREs]).

After baseline evaluation, patients were treated by the referring general practitioner or specialist until censoring on the basis of current guidelines. The number of events that occurred between baseline examination and the censoring date (June 17, 2006) for living patients or the date of death for fatal events were analyzed. Data concerning life status, causes of death, and hospitalization were collected by examination of the records of the following databases of the Ligurian Region (Italy): The Nominative Cause of Death Registry, the Hospitalization Discharge Records, and the Ligurian Resident Population Registry. Because 14 patients had moved out of town, information on vital status was obtained from their new local municipalities. The completeness of case findings from the sample was >98%. When an event was reported, original source documents were retrieved and reviewed to determine the occurrence of cardiovascular or renal disease. All possible events were audited independently by two members of the end points committee. Events were coded according to the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Development of CRI was defined as hospitalization with a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM codes 585 to 587). Incident cerebrovascular disease was defined as hospitalization with revascularization of a carotid artery or other cerebral arteries or with a diagnosis of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430 to 434, or 436, nonfatal event) or as death as a result of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430 to 434, or 436, fatal event). Incident ischemic heart disease was defined as hospitalization with revascularization of the coronary arteries or with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM codes 410 to 411 or 414, nonfatal event) or as death as a result of myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM codes 410 to 414, fatal event). In the case of a nonfatal event followed by a fatal event, priority was given to the nonfatal event.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD, with the exception of skewed variables (duration of hypertension, triglycerides, and ACR), which are expressed as the median and interquartile range. Logarithmically transformed values of skewed variables were used for the statistical analysis. The degree of association between variables was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient (r). Comparisons between groups were made by ANOVA. Comparisons of proportions among groups were made using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test when appropriate. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by exponentiation of logistic regression coefficients. Cumulative survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. To identify prognostic factors of CRI, CVE, and CRE, we made comparisons between survival curves by log-rank test. Cox regression was used (enter method) to determine the predictive power of microalbuminuria adjusted for variables that differed at baseline between patients who subsequently did or did not develop an event; an additional model of multivariate analysis took into account variables that are known to influence the outcome (age, gender, duration of disease, smoking habit, BMI, BP levels, serum glucose, uric acid, LDL cholesterol, and eGFR). Cubic splines were used to explore the functional form of the effects of albuminuria as a continuous variable on the risk for CRI. The results of the spline regression analysis are presented by plotting the hazard ratio as a spline function of the log albuminuria. In an additional attempt to reduce confounding with underlying renal disease, we performed analyses by excluding patients with eGFR <60 ml/min. In this subgroup (n = 796), the final model for the optimal prediction of CRI was fitted by backward elimination of insignificant baseline variables (P ≥ 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using Statview 5.0.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and, for the cubic-spline, Stata MP 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study cohort was composed of 917 patients who did not have diabetes and had hypertension and were aged 49 ± 10 years (median 51 years) without previous CVEs or known renal disease. The mean ± SD for the interval between the baseline examination and the censoring date was 11.2 ± 2.2 years. During 10,268 person-years of follow-up, 36 patients died for all cause and 22 reached a renal end point; the incidence rate was 3.5 and 2.1/1000 person-years, respectively.

At baseline, microalbuminuria was present in 36% (95% CI 19.51 to 56.71) of those who developed CRI compared with only 7% (95% CI 5.51 to 8.92) of control subjects (OR 7.48, 95% CI 3.03 to 18.72, P < 0.001; Table 1). Patients who had hypertensive and developed CRI were older and showed higher BP levels and worse renal function than those who remained free from renal end points. Table 2 shows baseline clinical characteristics of study patients on the basis of ACR levels. Patients with microalbuminuria were more likely male and showed higher BP and serum uric acid levels as compared with patients with normoalbuminuria, despite similar renal function and lipid profile. We found no association between basal levels of UAE and eGFR (r = 0.057, P = 0.102). Accordingly, the presence of microalbuminuria (n = 69) and eGFR reduction below 60 ml/min (n = 107) were also not related to each other (P = 0.52, χ2 0.40).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study patients who developed CRI and of control subjects with hypertension (n = 917)

| Characteristic | Controls for CRI (n = 895) | CRI (n = 22) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACR (mg/g; median [IQR]) | 4.42 (2.65 to 7.96) | 5.12 (2.56 to 56.48) | <0.001 |

| Microalbuminuria (%) | 7 | 36 | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 55 | 72 | 0.111 (NS) |

| Age (years; mean ± SD) | 49 ± 10 | 56 ± 9 | 0.006 |

| Duration of hypertension (months; median [IQR]) | 36 (12 to 84) | 30 (12 to 72) | 0.777 (NS) |

| Smoking habit, yes (%) | 43 | 48 | 0.552 (NS) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 26.1 ± 3.4 | 27.5 ± 3.5 | 0.071 (NS) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 160 ± 16 | 173 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 101 ± 8 | 107 ± 7 | 0.003 |

| Mean BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 121 ± 9 | 129 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 92 ± 10 | 91 ± 12 | 0.707 (NS) |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 0.193 (NS) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 0.92 ± 0.18 | 1.08 ± 0.25 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min; mean ± SD) | 83 ± 21 | 68 ± 19 | 0.002 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl; median [IQR]) | 150 (93 to 204) | 109 (79 to 153) | 0.106 (NS) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 218 ± 43 | 215 ± 39 | 0.750 (NS) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/d; mean ± SD) | 142 ± 38 | 136 ± 33 | 0.488 (NS) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study patients according to the presence/absence of microalbuminuria at baseline (n = 917)

| Characteristic | Normoalbuminuria (n = 848) | Microalbuminuria (n = 69) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACR (mg/g; median [IQR]) | 3.96 (2.67 to 6.63) | 53.91 (34.53 to 95.58) | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 54 | 72 | 0.004 |

| Age (years; mean ± SD) | 49 ± 11 | 51 ± 9 | 0.113 (NS) |

| Duration of hypertension (months; median [IQR]) | 36 (10 to 94) | 36 (12 to 60) | 0.814 (NS) |

| Smoking habit, yes (%) | 40 | 48 | 0.237 (NS) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 26.1 ± 3.4 | 26.8 ± 3.5 | 0.072 (NS) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 160 ± 16 | 165 ± 16 | 0.015 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 101 ± 8 | 105 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Mean BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 121 ± 9 | 125 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 92 ± 10 | 91 ± 11 | 0.325 (NS) |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 0.004 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 0.92 ± 0.18 | 0.96 ± 0.23 | 0.059 (NS) |

| eGFR (ml/min; mean ± SD) | 83 ± 21 | 81 ± 21 | 0.661 (NS) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl; median [IQR]) | 109 (79 to 153) | 115 (82 to 167) | 0.571 (NS) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 218 ± 43 | 214 ± 40 | 0.419 (NS) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl; mean ± SD) | 142 ± 38 | 136 ± 33 | 0.922 (NS) |

IQR, interquartile range.

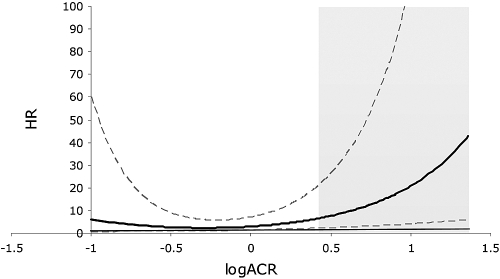

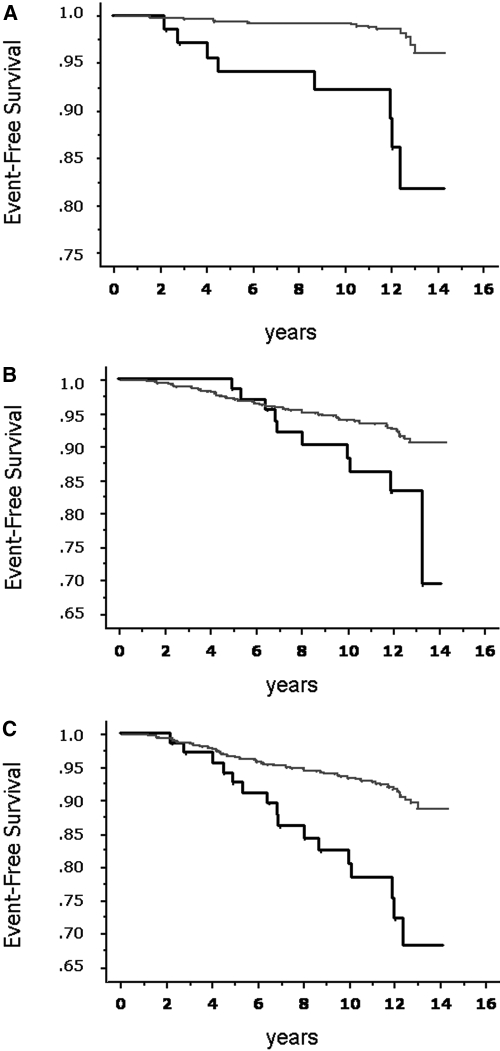

We investigated the role of several potential risk factors for the development of CRI. Microalbuminuria, ACR, decrease in eGFR, age, and BP increments all were significantly associated with the occurrence of CRI (Table 3). There was a clear dose-response relationship between ACR and the development of renal end points even after adjustment for several variables (Table 4). The relationship between ACR values and hazards for CRI, adjusted for gender, is presented as cubic-spline function in Figure 1. The increase in risk is steeper for patients within the range of microalbuminuria as shown by the hatched area. Patients with microalbuminuria showed higher incidence of CRI (12 versus 2%; OR 6.41; 95% CI 2.68 to 15.52; P < 0.001), as well as CVEs (15 versus 7%; OR 2.34; 95% CI 1.12 to 4.74; P = 0.029) and CRE (23 versus 8%; OR 3.52; 95% CI 1.91 to 6.38; P < 0.0001) than those with normoalbuminuria (Figure 2). Furthermore, during follow-up, patients with higher levels of albuminuria were hospitalized more frequently (4.1 ± 4.7 versus 2.9 ± 4.3; P = 0.022).

Table 3.

Unadjusted HRs with 95% CIs associated with risk factors for development of CRI (n = 917)

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Men versus women | 2.21 (0.86 to 5.62) | 0.099 |

| Age in 10-year increments | 1.89 (1.10 to 3.10) | 0.011 |

| Duration of disease in 1-year increments | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.06) | 0.539 |

| Smokers versus nonsmokers | 1.13 (0.83 to 1.12) | 0.338 |

| BMI in 1-kg/m2 increments | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.26) | 0.091 |

| Systolic BP in 10-mmHg increments | 1.31 (1.10 to 1.48) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP in 5-mmHg increments | 1.42 (1.16 to 1.76) | 0.002 |

| Fasting blood glucose in 1-mg/dl increments | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | 0.819 |

| Total cholesterol in 1-mg/dl increments | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.630 |

| HDL cholesterol in 1-mg/dl increments | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) | 0.972 |

| Serum uric acid in 1-mg/dl increments in men | 1.08 (0.73 to 1.56) | 0.656 |

| Serum uric acid in 1-mg/dl increments in women | 0.94 (0.47 to 2.02) | 0.939 |

| eGFR in 10-ml/min decrements | 1.53 (1.10 to 1.97) | 0.0035 |

| ACR in 10-mg/g increments | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.22) | <0.0001 |

HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

HR with 95% CIs for renal end point associated with albuminuria adjusted for other baseline characteristics

| Parameter | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| ACR adjusted for gender and age | 2.51 (1.15 to 5.47) | 0.0210 |

| ACR adjusted for eGFR | 3.14 (1.38 to 7.16) | 0.0063 |

| ACR adjusted for variables differing at baseline between patients who subsequently did or did not develop CRIa | 3.29 (1.34 to 8.11) | 0.0093 |

| ACR adjusted for variables known to influence outcomeb | 4.41 (1.56 to 12.49) | 0.0052 |

HR, hazard ratio.

Age, mean BP, and eGFR.

Gender, age, BMI, duration of hypertension, smoking habit, systolic BP, LDL cholesterol, eGFR, serum uric acid, and serum glucose.

Figure 1.

Gender-adjusted relationship between ACR levels and hazard ratio for development of CRI. Bold line shows the estimated relation when hazard is modeled as a cubic-spline function of logACR. Dashed lines are 95% CIs. Thin line marks 1 HR. Gray area represents the upper and lower limits of the current definition for microalbuminuria (ACR 2.5 to 30 mg/mmol).

Figure 2.

(A) Survival without CRI of patients with hypertension and microalbuminuria (n = 69; bold line) or normoalbuminuria (n = 848, thin line; P < 0.0001, log-rank test). (B) Survival without fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular end point in patients with hypertension and microalbuminuria (n = 69; bold line) or normoalbuminuria (n = 848; thin line; P < 0.028, log-rank test). (C) Survival without composite cardiorenal end point in patients with hypertension and microalbuminuria (n = 69; bold line) or normoalbuminuria (n = 848, thin line; P < 0.0001, log-rank test).

The unadjusted hazard ratio of microalbuminuria for CRI, CVE, and CRE was 7.61, 2.11, and 3.21, respectively, and remained significant when adjusted for gender (Table 5). Adjustment for other risk factors such as age, eGFR, BP values, BMI, duration of disease, smoking habit, serum glucose, uric acid, and LDL cholesterol improved or did not significantly alter the RR for CRI and CRE. Conversely, after adjustment for any confounding factors other than gender, the excess of risk for CVEs related to the presence of microalbuminuria lost statistical significance (Table 5). Table 6 shows the best model for prediction of de novo CRI in patients with hypertension. Analyses that were limited to patients with preserved basal eGFR >59 ml/min showed that albuminuria retained its predictive power. Furthermore, when male gender, systolic BP, and eGFR were included in the model, none of the other baseline variables that we measured in this study contributed to any significant further increase in the RR.

Table 5.

HR with 95% CIs for primary and composite end point associated with microalbuminuria and successively adjusted for other baseline characteristics

| Parameter | CRI (n = 22) |

CVE (n = 71) |

CRE (n = 85) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| MA versus NA | 7.61 (3.19 to 18.16) | <0.0001 | 2.11 (1.08 to 4.13) | 0.028 | 3.21 (1.86 to 5.53) | <0.0001 |

| MA versus NA adjusted for gender | 7.12 (2.97 to 7.05) | <0.0001 | 1.96 (1.00 to 3.85) | 0.049 | 3.01 (1.75 to 5.21) | <0.0001 |

| MA versus NA adjusted for gender and age | 5.32 (2.10 to 13.50) | 0.0004 | 1.46 (0.72 to 2.97) | 0.298 | 2.34 (1.32 to 4.13) | 0.0035 |

| MA versus NA adjusted for eGFR | 7.15 (2.79 to 8.06) | <0.0001 | 1.77 (0.80 to 3.92) | 0.156 | 3.00 (1.64 to 5.48) | 0.0004 |

| MA versus NA adjusted for variables differing at baseline between patients who subsequently did or did not develop an eventa | 7.77 (2.86 to 21.08) | <0.0001 | 1.24 (0.52 to 2.98) | 0.629 | 2.31 (1.18 to 4.51) | 0.0140 |

| MA versus NA adjusted for variables known to influence outcomeb | 14.10 (3.12 to 60.91) | 0.0006 | 1.11 (0.42 to 2.95) | 0.829 | 2.33 (1.12 to 4.84) | 0.0235 |

HR, hazard ratio; MA, microalbuminuria; NA, normoalbuminuria.

For CRI = age, mean BP, and eGFR; for CVE = gender, age, duration of hypertension, smoking habit, systolic BP, and total cholesterol; for CRE = gender, age, duration of hypertension, smoking habit, systolic BP, and eGFR.

Gender, age, BMI, duration of hypertension, smoking habit, systolic BP, LDL cholesterol, eGFR, serum uric acid, and serum glucose.

Table 6.

Final model for prediction of CRI in 796 patients with hypertension, without diabetes, and with baseline GFR >59 ml/min

| Parameter | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Variable in final model | ||

| microalbuminuria | 7.82 (1.43 to 42.65) | 0.018 |

| male gender | 10.99 (1.05 to 114.6) | 0.045 |

| systolic BP in 10-mmHg increments | 2.18 (1.21 to 3.70) | 0.008 |

| eGFR in 10-ml/min decrements | 2.82 (1.22 to 4.81) | 0.013 |

| Variable not included in final model | ||

| age | 0.79 | |

| BMI | 0.41 | |

| duration of disease | 0.09 | |

| smoking habit | 0.70 | |

| serum glucose | 0.25 | |

| serum uric acid | 0.45 | |

| LDL cholesterol | 0.73 |

All variables were initially entered in the model, and, if insignificant (P ≥ 0.05), they were successively excluded by the conditional backward elimination method.

Discussion

This study shows that, during long-term follow-up, microalbuminuria is a powerful predictor of CRI and CVEs in patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension. The excess of risk associated with increased albuminuria was independent of eGFR and other potential confounders. Interestingly, whereas the relationship between ACR and a renal end point was continuous and already apparent for levels of albuminuria that are currently considered to be normal, the risk for developing a renal end point increased substantially when microalbuminuria was present. The unadjusted as well as the fully adjusted hazard ratios for the development of CRI conferred by the presence of microalbuminuria at baseline were far greater than those attributable to a 10-year increment in age, to a 10-ml/min decrease in eGFR, and to a 10- and 5-mmHg increment in systolic and diastolic BP levels, respectively.

Microalbuminuria has been shown to be an intermediate end point and a powerful predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes. In particular, the degree of albuminuria is strongly related both to the progression of diabetic renal disease and to the risk for CVEs (18). Dipstick urinalysis for proteinuria (19) and micro- or macroalbuminuria (5,14) were previously reported to predict renal outcome in the general population. These data, however, need to be interpreted with some caution. Within an Australian Aboriginal community (13), renal failure developed only in patients with overt albuminuria at baseline and largely, although not exclusively, was limited to those with a preexisting reduction of GFR. Similarly, in the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease (PREVEND) study (14), >55% of individuals who reached ESRD during the follow-up period were already known to have renal function impairment at baseline. Noteworthy, in our study, the renal predictive power of microalbuminuria persisted even after exclusion of patients with eGFR <60 ml/min at baseline from the analysis. In fact, even in this subgroup (n = 796), we recorded a greater incidence of CRI in patients with microalbuminuria than in those with normoalbuminuria (5 versus 1%; OR 4.72; 95% CI 1.24 to 17.89; P = 0.044).

Data on the predictive role of an increase in the urinary excretion of albumin in terms of progression of renal damage are scanty in patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension. In this regard, our data confirm and extend, in a much larger study group, preliminary results by Bigazzi et al. (20), who published a report on 141 patients, that suggested that microalbuminuria at baseline was associated with a greater decline in renal function during a seven-year observation period. The study, however, suffered from several limitations, such as the small sample size and the retrospective design. Since then, no other studies have been published supporting the role of microalbuminuria as a forerunner of progressive renal damage in nondiabetic hypertension.

Potential Mechanisms

A number of factors could explain the predictive role of microalbuminuria with regard to overt renal disease. The clustering of microalbuminuria with traditional risk factors (21) may provide insight as to why the outcome in this subgroup was significantly worse. In fact, the excess of renal events that we observed in our patients with microalbuminuria persisted despite adjustment for several confounding factors, suggesting that additional mechanisms may be responsible for these associations.

Univariate regression analysis showed that ACR (r = 0.18, P < 0.001), eGFR, (r = −0.11, P = 0.002), systolic BP level (r = 0.12, P < 0.001), diastolic BP level (r = 0.10, P = 0.003), and age (r = 0.09, P = 0.006) all were predictors of CRI. At logistic multivariate analysis, however, ACR was the only independent predictor of CRI (RR 1.18; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.32 for each 10-mg/g increment in ACR; P = 0.001). This suggests that although hypertension, age, and basal renal function are widely known risk factors for renal disease, the presence of microalbuminuria entails an even greater risk for developing renal events.

Although our findings do not prove a cause–effect relationship between microalbuminuria and decline in renal function, they do suggest that patients with microalbuminuria be targeted for aggressive cardiovascular and renal risk factors so as to have a favorable impact on renal outcome. The lack of association that we found between UAE and eGFR at baseline is at least in part at variance with other studies and could be related to selection criteria that led to the exclusion of high-risk patients and those with overt renal damage.

As for the positive association that we found between ACR and CVE, this is consistent with results of previous studies (22,23). In our cohort, however, this relationship lost statistical power when adjusted for variables that were potentially related to cardiovascular outcome, such as age, smoking habits, BP, and lipid profile. These findings could be due to a number of confounding factors that were not taken into consideration in our study, such as the treatment of hypertension or other cardiovascular risk factors during the follow-up period. Furthermore, the relatively small number of events recorded in the study period may help to explain the lack of association after adjustment.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has both strengths and limitations. The former include the rigorous method that we applied to the collection of urine samples and measurement of albuminuria. Moreover, the stringent criteria used for patient recruitment at baseline (all patients without diabetes or a history of CVEs) allowed us to select a fairly homogeneous group, which adds to the clarity and power of our study findings. The ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes that we used to adjudicate end points have proved to be highly specific for detecting CRI, although it has been noted that they may lack in sensitivity (24). It is indeed possible that in this study, we underestimated the prevalence of new-onset CRI. Similarly, the selection criteria may have been the reason for the relatively small number of events that were recorded, thereby causing an underestimation of the association between microalbuminuria and cardiovascular and renal end points and limiting the power of our study. Although it is widely acknowledged that GFR estimation using equations has a certain degree of inaccuracy, the use of the Cockcroft-Gault equation corrected for ideal body weight provides an acceptable way to estimate GFR in this clinical setting. Finally, we have no definitive data to address the relationship between cardiovascular and renal risk associated with microalbuminuria on the basis of the type of treatment or the achieved BP level.

Perspectives

On the basis of these results, patients without diabetes and with primary hypertension and microalbuminuria do show an increased risk for developing CRI, even after adjustment for several baseline confounding variables, including eGFR. Our findings, which indicated an almost sevenfold higher risk for CRI in patients with microalbuminuria, emphasize the usefulness of a more widespread evaluation of ACR in an effort to guide the management of hypertension. Patients with microalbuminuria should be aggressively targeted for renal and cardiovascular risk factor reduction, although further research is warranted to determine whether specific treatment would help to improve outcomes, as already reported for patients with diabetes (10).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity. We all have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

We thank Clizia Nicolella, Denise Parodi, Elena Ratto, Maura Ravera, Antonella Sofia, Angelito Tirotta, and Simone Vettoretti for support in the clinical treatment of patients. Moreover, we thank Mariapia Sormani for assistance with the statistical analysis that we performed during the review process.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Astor B, Sarnak MJ: Evidence for increased cardiovascular disease risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13: 73–81, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX: Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2034–2047, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culleton BF, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Evans JC, Parfrey PS, Levy D: Cardiovascular disease and mortality in a community-based cohort with mild renal insufficiency. Kidney Int 56: 2214–2219, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romundstad S, Holmen J, Kvenild K, Hallan H, Ellekjaer H: Microalbuminuria and all-cause mortality in 2,089 apparently healthy individuals: A 4.4-year follow-up study. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), Norway. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 466–473, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, van Gilst WH, de Zeeuw D, van Veldhuisen DJ, Gans RO, Janssen WM, Grobbee DE, de Jong PE, Prevention of Renal and Vascular End Stage Disease (PREVEND) Study Group: Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 106: 1777–1782, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Hallé JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, Nawaz S, Yusuf S, HOPE Study Investigators: Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 286: 421–426, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibsen H, Wachtell K, Olsen MH, Borch-Johnsen K, Lindholm LH, Mogensen CE, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wan Y, LIFE substudy: Does albuminuria predict cardiovascular outcome on treatment with losartan versus atenolol in hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy? A LIFE substudy. J Hypertens 22: 1805–1811, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibsen H, Olsen MH, Wachtell K, Borch-Johnsen K, Lindholm LH, Mogensen CE, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wan Y: Reduction in albuminuria translates to reduction in cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: Losartan intervention for endpoint reduction in hypertension study. Hypertension 45: 198–202, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogensen CE: Microalbuminuria and hypertension with focus on type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med 254: 45–66, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann JF, Gerstein HC, Yi QL, Lonn EM, Hoogwerf BJ, Rashkow A, Yusuf S: Development of renal disease in people at high cardiovascular risk: Results of the HOPE randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 641–647, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhave JC, Gansevoort RT, Hillege HL, Bakker SJ, De Zeeuw D, de Jong PE, PREVEND Study Group: An elevated urinary albumin excretion predicts de novo development of renal function impairment in the general population. Kidney Int Suppl 92: S18–S21, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoy WE, Wang Z, VanBuynder P, Baker PR, McDonald SM, Mathews JD: The natural history of renal disease in Australian Aborigines. Part 2: Albuminuria predicts natural death and renal failure. Kidney Int 60: 249–256, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Velde M, Halbesma N, de Charro FT, Bakker SJ, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE, Gansevoort RT: Screening for albuminuria identifies individuals at increased renal risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 852–862, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontremoli R, Sofia A, Ravera M, Nicolella C, Viazzi F, Tirotta A, Ruello N, Tomolillo C, Castello C, Grillo G, Sacchi G, Deferrari G: Prevalence and clinical correlates of microalbuminuria in essential hypertension: The MAGIC Study. Microalbuminuria—A Genoa Investigation on Complications. Hypertension 30: 1135–1143, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorentz FH: A new index of conformation [in German]. Klin Wochenschr 8: 348–351, 1929 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH: Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16: 31–41, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mogensen CE, Poulsen PL: Microalbuminuria, glycemic control, and blood pressure predicting outcome in diabetes type 1 and type 2. Kidney Int Suppl 92: S40–S41, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Iseki C, Takishita S: Proteinuria and the risk of developing end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 63: 1468–1474, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bigazzi R, Bianchi S, Baldari D, Campese VM: Microalbuminuria predicts cardiovascular events and renal insufficiency in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens 16: 1325–1333, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parving HH: Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension and diabetes mellitus. J Hypertens Suppl 14: S89–S93, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Olsen MH, Borch-Johnsen K, Lindholm LH, Mogensen CE, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Kristianson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Nieminen MS, Okin PM, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H, Snapinn SM, Aurup P: Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: The LIFE Study. Ann Intern Med 139: 901–906, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S, Schroll M, Borch-Johnsen K: Arterial hypertension, microalbuminuria, and risk of ischemic heart disease. Hypertension 35: 898–903, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kern EF, Maney M, Miller DR, Tseng CL, Tiwari A, Rajan M, Aron D, Pogach L: Failure of ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res 4: 564–580, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]