Abstract

Background and objectives: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a disorder that can affect patients with renal dysfunction exposed to a gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA). Given the unique role nephrologists play in caring for patients at risk to develop NSF, this study surveyed their perceptions and practices regarding NSF.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: An internet-based, cross-sectional survey of clinical nephrologists in the United States was performed. Perceptions and self-reported practices regarding NSF and local facility policies were assessed concerning GBCA use in renal dysfunction.

Results: Of the 2310 eligible nephrologists e-mailed to participate in the survey, 171 (7.4%) responded. Respondents spent 85% of their time in direct patient care and 83% worked in private practice; 59% had cared for a patient with NSF. Although over 90% were aware of the morbidity and mortality associated with NSF, 31% were unaware of an association with specific GBCA brand and 50% believed chronic kidney disease stage 3 patients were at risk to develop NSF. Changes in facility policies concerning GBCA use in renal dysfunction were widespread (>90%). Most nephrologists (56%) felt that enacted policies were appropriate, yet 58% were uncertain if the changes had benefited patients.

Conclusions: These results indicate that nephrologists are generally familiar with the risk factors and consequences of NSF, but their perceptions do not always align with current evidence. Local policy changes in GBCA use are pervasive. Most nephrologists are comfortable with these policy changes but have mixed feelings regarding their effectiveness.

In 1997, several patients at a southern California hemodialysis center developed symptoms of a previously unknown fibrosing skin disorder (1). Skin biopsies revealed lesions similar to scleromyxedema. Subsequently, further cases were recognized and renal dysfunction was conspicuously present in all affected patients. Although no clear etiology could be identified, researchers later noted that this new disease (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy) could affect multiple systems, with documented fibrosis in the heart, liver, lungs, skeletal muscle, and other organs (2–5). In light of these observations, the disease was redesignated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) (2–7).

In 2006, Grobner suggested a link between gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) and NSF (8). A second report that same year further supported a causative role for GBCAs in the development of NSF (9). Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning to healthcare professionals and the public regarding the potential risks of NSF after GBCA exposure in patients with renal dysfunction. Since then, numerous studies have corroborated an association between GBCA and NSF (10–16), and in 2007 the FDA required the addition of a black box warning for all GBCAs (17).

This warning notified healthcare providers about the risk of developing NSF after GBCA exposure in patients with acute or chronic kidney disease with a GFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2 or acute kidney injury (AKI) of any degree due to the hepatorenal syndrome or in the setting of a liver transplant (17). In addition to screening for renal dysfunction and avoiding GBCA use in high-risk scenarios unless essential, the FDA also recommended avoiding repeated or high doses of GBCAs in patients with renal dysfunction. In patients receiving hemodialysis (HD) that are administered a GBCA, the FDA recommended considering prompt HD postexposure while acknowledging that this prophylactic approach was unproven (17).

Despite the discovery of gadolinium as a key factor in the development of NSF in patients with renal dysfunction, relatively little else is firmly known regarding other contributing factors, the natural history of the disease, or effective treatments (16,18–21). Nearly all patients with documented NSF had chronic kidney disease (CKD) with an estimated GFR (eGFR) < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 or AKI. In addition to renal dysfunction, potential associations with liver transplant, vascular injury, inflammatory processes, and high doses of erythropoietin stimulating agents have been theorized (16,18,20,22).

Frequently, clinical nephrologists and their patients confront difficult risk-benefit considerations when choosing whether to use imaging studies with GBCAs. Since 2007, multiple publications have reported on local changes in radiology and/or hospital policies regarding the use of GBCAs in patients with renal dysfunction (23–26). Some of these reports document potentially improved outcomes, including a lower incidence of NSF, after the introduction of new, restrictive departmental or institutional guidelines (24). Conversely, others have anecdotally reported on the potential detrimental effects of delayed or missed diagnoses (e.g., a malignancy) because of these changes (23). Given the relative rarity of NSF [approximately 315 cases of NSF have been identified as of June, 2009 (27)], many nephrologists are unlikely to possess an abundance of clinical experience with the disease to help make these challenging risk-benefit decisions. Limitations in clinical experience and our inadequate knowledge of NSF are likely to influence nephrologists' beliefs and practices regarding the disease and the policies established to reduce the risk of developing it. Because nephrologists' play a vital role in caring for and advising the patients most affected by the risks and benefits of undergoing a study with GBCA exposure, it is useful to understand their perceptions and practices concerning NSF and GBCAs. We surveyed clinical nephrologists on their perceptions and practices regarding NSF and GBCAs. We also explored whether clinical experience with this rare disease was associated with differences in responses.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Setting

A web-based, cross-sectional survey of U.S. nephrologists was performed between October 2008 and March 2009. The sample frame was nephrologists with an active membership in the Renal Physicians Association (RPA), licensed to practice medicine in the United States, and having completed their training in nephrology. Of 3700 RPA members, 2310 were eligible for participation in this survey.

Survey Design

The survey included questions assessing nephrologists' beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding NSF as well as demographic and practice characteristics. Survey items were developed after appraisal of the literature by two nephrologists (K.A., M.U.), two physician epidemiologists (P.P., A.K.), and a researcher with expertise in survey design (R.C.). The initial survey was reviewed and revised with the assistance of two additional faculty members at the University of Pittsburgh with expertise in survey design and implementation. Subsequently, the questionnaire was pilot tested by physicians in the University of Pittsburgh's Renal Division. Revisions to the questionnaire's content and configuration were made based on feedback received during pilot testing. The survey was then formatted for web-based implementation. A researcher with expertise in survey design reviewed the internet-based survey for format and user-friendliness. The final questionnaire contained 27 items concerning NSF, CKD, and GBCAs and 5 demographic questions (see Supplemental Appendix).

Survey Implementation

Through RPA distribution, all eligible members received an e-mail inviting them to participate in the survey. The invitation included a link to the web-based questionnaire. To enhance participation, the RPA sent a second dedicated e-mail to nonresponders 4 months after the initial e-mail. The invitation also ensured the confidentiality of participant responses and that only aggregate data would be analyzed. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze survey responses. Continuous variables were summarized using means and SD, whereas ordinal and categorical variables were summarized using percentages and frequencies. Fisher's exact test was used to assess independence of categorical variables. Logistic or ordinal logistic regression was used to assess for associations between involvement in the care of a patient with NSF (assessed by “Have you been involved in the care of a patient with NSF?”) or an academic practice setting (assessed by “Which best describes your practice setting?”) and items assessing nephrologists' perceptions and practices. For all analyses, P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using STATA version 10.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Of the 2310 eligible nephrologists who were e-mailed, 171 (7.4%) responded. Four respondents failed to complete the entire survey, each answering between 13 and 23 questions. Over 94% of respondents spent at least 50% of their time in direct patient care (data not shown). Respondents' demographic and practice characteristics are shown in Table 1. Respondents were predominantly in private and group practices. Nearly 59% of respondents reported ever being involved in the care of a patient with NSF. Compared with aggregate data available on eligible RPA members, respondents were more likely to practice in an academic setting (15.6% versus 9.7%, P = 0.02) than a private practice (83.2% versus 90.3%). Respondents were less likely to be in a solo practice (12.0% versus 20.9%, P = 0.02) and more likely to be in a group (73.1% versus 69.4%) or university practice (13.2% versus 9.7%).

Table 1.

Baseline respondent characteristicsa

| Percent clinical time | 85.1 (18.4) |

|---|---|

| Years since fellowship training | 18.7 (9.9) |

| Practice setting (%) | |

| hospital-based | 43.1 (72) |

| nonhospital-based | 46.1 (77) |

| both | 10.8 (18) |

| academic | 15.6 (26) |

| private | 83.2 (139) |

| government | 0.6 (1) |

| Practice organization (%) | |

| solo/two-person | 12.0 (20) |

| group | 73.1 (122) |

| university | 13.2 (22) |

| government | 1.2 (2) |

| Ever involved in the care of an NSF patient (%) | |

| yes | 58.7 (98) |

| no | 41.3 (69) |

n = 167 for all responses. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD). Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and N.

Nephrologists' Perceptions

As shown in Table 2, most nephrologists (>90%) believed they were knowledgeable about the evidence linking NSF and GBCAs. The overwhelming majority of nephrologists recognized that NSF could be a severely debilitating disease and potentially life-threatening and that GBCAs were a causal factor. Approximately two-thirds recognized an association between the brand of gadolinium used and the risk of developing NSF. Although nearly all respondents believed that CKD stage 5 patients administered a GBCA were at risk to develop NSF, 86% believed that CKD stage 4 patients were also at risk, and over 50% believed CKD stage 3 patients were at risk. Respondents were generally uncertain whether peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients were at higher risk to develop NSF than HD patients.

Table 2.

Nephrologists' knowledge and beliefs regarding NSFa

| Strongly Agree % (N) | Agree % (N) | Disagree % (N) | Strongly Disagree % (N) | Do Not Know % (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am knowledgeable about the evidence linking gadolinium to NSF. | 21.1 (36) | 69.0 (118) | 7.0 (12) | 0.6 (1) | 2.3 (4) |

| NSF can be severely debilitating. | 80.7 (138) | 18.7 (32) | 0 | 0 | 0.6 (1) |

| NSF can be life threatening. | 50.3 (86) | 39.8 (68) | 5.8 (10) | 1.2 (2) | 2.9 (5) |

| Gadolinium-containing MRI contrast is a cause of NSF. | 35.1 (60) | 57.9 (99) | 1.8 (3) | 0 | 5.3 (9) |

| Some brands of gadolinium contrast are more likely to cause NSF than others. | 24.0 (41) | 45.0 (77) | 5.8 (10) | 0.6 (1) | 24.6 (42) |

| A patient with stage 5 CKD administered a standard dose of gadolinium is at risk for developing NSF. | 57.9 (99) | 38.6 (66) | 1.8 (3) | 0 | 1.8 (3) |

| A patient with stage 4 CKD administered a standard dose of gadolinium is at risk for developing NSF. | 21.1 (36) | 64.9 (111) | 6.4 (11) | 0.6 (1) | 7.0 (12) |

| A patient with stage 3 CKD administered a standard dose of gadolinium is at risk for developing NSF. | 5.8 (10) | 44.4 (76) | 25.7 (44) | 6.4 (11) | 17.5 (30) |

| PD patients administered a standard dose of gadolinium are at higher risk for developing NSF than HD patients. | 12.3 (21) | 29.2 (50) | 14.6 (25) | 0 | 43.9 (75) |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

N for each item is 171.

Facility Practices

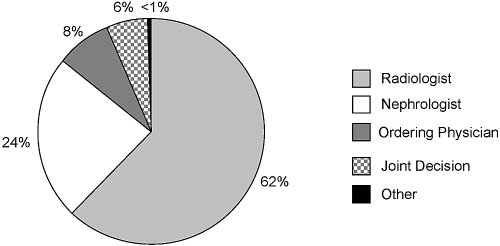

Radiologists were most frequently (62%) responsible for approving the use of GBCAs in a patient with renal dysfunction, as seen in Figure 1. However, 24% of respondents reported that nephrologists were primarily responsible. Similarly, 21% reported that a nephrology consultation was required before GBCA use in a patient with renal dysfunction. Over 90% of respondents reported that practice changes had occurred at their primary facility regarding the use of GBCAs in patients with renal dysfunction, as shown in Table 3. However, many respondents were uncertain concerning the specifics of these policy changes, as seen in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Primary responsibility for approving the administration of gadolinium to a patient with renal dysfunction (n = 169).

Table 3.

Reported primary facility practices regarding gadolinium and NSF

| Question | Yes % (N) | No % (N) | Do Not Know % (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have any modifications in practice occurred regarding the use of gadolinium in patients with renal dysfunction?a | 91.2 (156) | 6.4 (11) | 2.3 (4) |

| Is there a specific written policy that addresses the administration of gadolinium to patients with ESRD?a | 42.7 (73) | 38.6 (66) | 18.7 (32) |

| Have modifications been made in the maximum allowable single dose of gadolinium administered to ESRD patients?b | 36.1 (56) | 33.5 (52) | 30.3 (47) |

| Have modifications been made in the maximum allowable cumulative dose of gadolinium administered to ESRD patients?b | 28.4 (44) | 38.7 (60) | 32.9 (51) |

| Have modifications been made in the brand of gadolinium contrast administered to ESRD patients?b | 24.5 (38) | 37.4 (58) | 38.1 (59) |

| Is a nephrology consultation required before using gadolinium in a patient with renal dysfunction?c | 21.3 (36) | 70.4 (119) | 8.3 (14) |

n = 171.

n = 155 of 156 respondents who endorsed any modifications in facility practice.

n = 169.

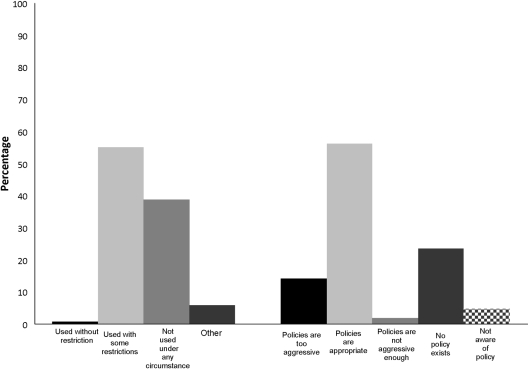

When characterizing their facility's policy toward GBCA use in ESRD, most respondents (55%) felt use was partially restricted, as shown in Figure 2. An additional 39% reported that GBCA use was not permitted under any circumstance in patients with ESRD. Most nephrologists (56%) felt these policies were appropriate (Figure 2), although 14% felt the policies were too restrictive. Respondents reporting that GBCA use in ESRD was forbidden at their facility were not more likely to report that their facility's policies were too restrictive (P = 0.3, data not shown).

Figure 2.

Facilities' policies regarding the use of gadolinium in ESRD and nephrologists' attitudes toward those policies.

Nephrologists' Practices

Many respondents (31%) reported that they did not recommend an extra HD session for their maintenance HD patients after the administration of GBCAs, as shown in Table 4. Respondents were unlikely to recommend an HD treatment to their maintenance PD (28%), CKD stage 5 (25%), or CKD stage 4 (13%) patients. For maintenance HD patients exposed to GBCAs who received an extra HD treatment, nephrologists reported that the extra session was started within 1 hour (20%) or between 1 and 6 hours (70%) after exposure.

Table 4.

Interventions recommended by nephrologists after the administration of gadolinium agent

| Yes % (N) | No % (N) | Do Not Know/ Not Applicable % (N)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| An extra HD treatment for maintenance HD patientsb | 69.4 (118) | 12.9 (22) | 17.6 (30) |

| A HD treatment for maintenance PD patientsc | 27.8 (47) | 43.8 (74) | 28.4 (48) |

| A HD treatment for nondialysis-dependent stage 5 CKD patientsc | 25.4 (43) | 39.1 (66) | 35.5 (60) |

| A HD treatment for stage 4 CKD patientsc | 13.0 (22) | 58.0 (98) | 29.0 (49) |

Do not know and not applicable responses were joined.

n = 170.

n = 169.

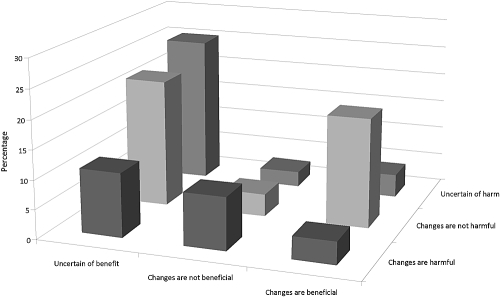

Respondents were largely uncertain whether changes in practice had benefited or harmed patients. Over 58% were uncertain if the changes had beneficial effects on patients, whereas 32% were uncertain if the changes had harmful effects on patients. Interestingly, a similar percentage of respondents reported that practice changes resulted in benefits (27%) and reported that the changes resulted in harm (24%). Examining responses to these two questions together, one-quarter of respondents were uncertain if changes had produced positive or negative consequences, as shown in Figure 3. Another 22% were uncertain if changes had resulted in benefits but felt that they had not caused harm. Approximately 19% believed that changes resulted in beneficial consequences without detrimental effects for patients. Nephrologists reported that their practices were most frequently influenced by specialty society/national organization guidance (53%), liability concerns (49%), clinical experience with the disease (41%), facility policy (30%), opinions of colleagues (25%), and medical literature (10%).

Figure 3.

Perceived beneficial and harmful consequences of facility changes in gadolinium use on patients with renal dysfunction. P < 0.001 (Fisher's exact test).

Experience with NSF

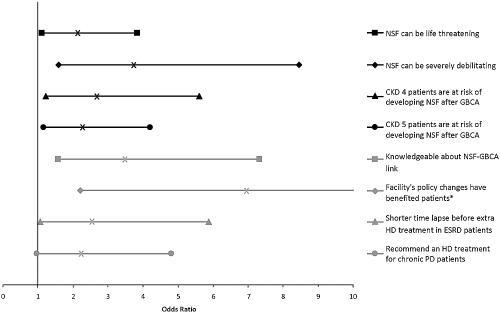

Approximately 40% of respondents reported that they were not aware of any patients diagnosed with NSF at their dialysis center. Another 42% reported that between one and three patients had been diagnosed with NSF at their dialysis center. Only 10% of respondents reported four or more patients diagnosed with NSF, whereas 8% of respondents were uncertain of the number of patients with NSF at their dialysis center. As shown in Figure 4, personally caring for a patient with NSF was associated with nephrologists' responses to multiple survey questions assessing perceptions and practices.

Figure 4.

Experience of caring for NSF patients with item response. *Upper limit of 95% CI is 21.3.

Association with Practice Setting

Approximately 16% of responding nephrologists reported practicing in an academic setting (versus private practice). These respondents were more likely to report that their facility had a written policy regarding the use of GBCAs in ESRD [odds ratio (OR): 4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6 to 10.3], that their facility required a renal consultation before GBCA use in the setting of renal dysfunction (OR: 2.9, 95% CI: 1.2 to 7.4), and that a larger number of patients had been diagnosed with NSF at their dialysis center (OR: 2.9, 95% CI: 1.2 to 6.7). Academic nephrologists were less likely to report liability concerns as a major factor influencing their use of GBCAs in the setting of renal dysfunction (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.68).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess nephrologists' perceptions and practices regarding GBCAs and NSF. Our findings indicate that many nephrologists (approximately 40%) have not cared for a patient with NSF and are not aware of any patients with NSF at their dialysis center. Nonetheless, most nephrologists were well informed of the debilitating and potentially life-threatening nature of NSF and the risk of developing NSF in CKD stage 5 patients administered a GBCA. Changes in facility practices appeared to be pervasive, with over 90% of respondents acknowledging that changes had occurred at their facility regarding the use of GBCAs in the setting of renal dysfunction. Most nephrologists (56%) felt that the policies established at their institution were appropriate, yet they were also generally uncertain (58%) whether these changes benefited patients. Nephrologists who had personally cared for a patient with NSF were more likely to believe that their facility's policy changes had benefited patients.

As expected, the overwhelming majority of nephrologists reported that changes in facility practices had occurred regarding GBCA use in renal dysfunction. These changes included the implementation of partial restrictions or the outright prohibition of GBCA use in ESRD patients. These changes were well received by most respondents, although a minority (14%) felt the restrictions were too aggressive. Surprisingly, 23% of nephrologists were unaware of the existence of any facility policy and most were unaware of a formal, written institutional policy regarding the use of GBCAs, the dose administered, or the brand utilized. We were unable to discern whether this was due to a lack of official institutional policies or the need to improve local dissemination of these policies. Formal local policies are important to ensure practices regarding GBCA use in patients with renal dysfunction represent established recommendations. Indeed, 30% of respondents reported that their facility's policy had a large influence on their practice regarding GBCA use in patients with renal dysfunction. Because we are the primary physician advocates for patients with renal disease, nephrologists should be actively involved in helping to create these policies.

When formal policies already exist, better communication of these policies may allow nephrologists to more fully inform patients of the precautions that are being taken to minimize the risk of NSF. Furthermore, knowledgeable nephrologists may advocate for alternative or additional measures to decrease the risk of NSF or to avoid overly restrictive policies that are unlikely to benefit low-risk patients. This, along with future research advances, may begin to address the mixed feelings expressed by most respondents who reported that they were uncertain whether policy changes had benefited or harmed patients.

Our survey indicates that nephrologists are generally aware of the potential morbidity and mortality associated with NSF, the link to GBCAs, and the risk to CKD stage 5 patients exposed to a GBCA. However, respondents' perceptions were not always well aligned with the available evidence. For example, nearly one-third of respondents did not believe that gadolinium brand played a role in NSF risk. Recent publications comparing various GBCAs have shown differences in the incidence of NSF or NSF-like changes in humans and animals (28–32), and the European Medicines Agency and the European Society of Urogenital Radiology have published recommendations classifying agents into low, intermediate, or high risk for causing NSF in patients with renal dysfunction (33). A recently convened FDA advisory panel also recommended differentiating between GBCAs (34,35); however, current FDA guidelines do not differentiate between GBCA brands, and surveyed U.S. nephrologists may not be aware of the existing literature or may not be convinced by it. Further studies investigating the role that gadolinium chelate structure and charge may play in the risk of developing NSF are needed. Nephrologists should consider chelate factors when GBCA use cannot be avoided in a patient with renal dysfunction; these issues have been reviewed in the literature (18,36).

Additional areas where respondents' perceptions may not fully agree with the available evidence were also uncovered. Approximately 14% of respondents felt that CKD stage 4 patients administered a standard dose of GBCAs were not at risk to develop NSF; however, studies and reviews have documented this risk, albeit low (37,38). Patients and providers need to consider this risk when making decisions to pursue imaging studies with GBCAs in CKD stage 4 patients. Interestingly, 50% of nephrologists believed that stage 3 CKD patients were at risk to develop NSF after GBCA use. Although case reports of NSF in patients with stage 3 CKD exist, they have been in the setting of superimposed AKI (39). Rare reports of NSF in the setting of stable, very late stage 3 CKD exist (34); however, these reports have been limited by variation and imprecision in reported eGFR values. Plausibly, a very small risk of NSF may exist in patients with stable, late stage 3 CKD, although this has not been convincingly demonstrated. With millions of stage 3 CKD patients in the United States and across the world (40,41), restricting the use of GBCAs in stage 3 CKD (especially early stage 3 CKD which is more prevalent) could have a significant effect on the care of many patients. Our survey findings indicate that further educational efforts are needed to bridge the knowledge gap between available NSF literature and nephrologists' perceptions. Future continuing medical education activities and local expert outreach efforts will likely be needed to address this problem. Further studies should also elaborate on potential differences in NSF perceptions and practices between academic and private nephrologists. Such information could guide future educational initiatives and help them better target their audience's needs.

Some nephrologists may believe that an intimate knowledge of NSF is not required because issues regarding screening and consenting patients fall primarily into a radiologist's purview. However, we found that nearly one-quarter of respondents reported that nephrologists were ultimately responsible for approving the use of GBCAs in patients with renal dysfunction. Similarly, over 20% of responding nephrologists reported that a formal nephrology consultation was required to assess NSF risk before gadolinium could be administered to a patient with renal dysfunction. These findings highlight the important role nephrologists are playing in assessing the risks and benefits of studies requiring GBCAs and the need to ensure that our practices are consistent with the growing body of literature on NSF.

Our survey also suggests that national organizations might play an important role in shaping nephrologists' practices and beliefs, because more than half of respondents reported they were greatly influenced by these institutions. Indeed, approximately 70% of nephrologists agreed with the FDA's recommendation to perform HD promptly after a HD patient was exposed to a GBCA despite its unproven efficacy. Whether this is due to a belief in expert opinions, liability concerns, or other factors is unclear.

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. The response rate for our survey was low, and this may reduce generalizability. Respondents to this survey may be self-selected and therefore substantively different from nonresponders (e.g., more knowledgeable and interested in NSF or alternatively less knowledgeable), potentially limiting the external validity of our findings. We attempted to enhance the response rate by sending out a reminder e-mail and including the academic institutional affiliation of the researchers on the survey invitation and webpage. However, we targeted a difficult group to survey—nephrologists with a very active clinical practice. We felt this group of physicians would be most representative of the specialists that kidney disease patients are likely to encounter and hence best reflect “every-day practice.” The respondents to our survey were overwhelmingly clinicians in a group or solo private practice who spent the greater part of their work time in direct patient care, generally representative of most U.S. nephrologists and the targeted sample frame—RPA physicians. Another limitation is recall and misclassification bias (e.g., nephrologists may not accurately recall the number of patients with NSF that they have cared for or their local facility's policies).

In conclusion, our findings indicate that many nephrologists have not personally cared for a patient with NSF, and although they are aware of the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease, their perceptions do not always agree with the literature. Although changes in GBCA use have been adopted at most facilities, many nephrologists are unaware of the particulars of these changes. Although most nephrologists were generally comfortable with local changes in GBCA policy, significant uncertainty remains regarding the beneficial effects of these policies on patients. Research is needed to identify additional risk factors for NSF, further describe the incidence of NSF in high-risk patients receiving potentially lower-risk GBCA agents, and determine optimal practices to avoid harm while maximizing the benefits derived from GBCA studies.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank Dale Singer and the RPA for their assistance. This work was supported by a National Kidney Foundation Clinical Research Fellowship and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Institutional Research Training Grant (T32-DK061296, K.A.K.). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.cjasn.org/.

References

- 1. Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE: Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet 356: 1000–1001, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cowper SE: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: The nosological and conceptual evolution of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 763–765, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowper SE, Bucala R: Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: Suspect identified, motive unclear. Am J Dermatopathol 25: 358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, Kurtz K: Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol 139: 903–906, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibson SE, Farver CF, Prayson RA: Multiorgan involvement in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: An autopsy case and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 130: 209–212, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LeBoit PE: What nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy might be. Arch Dermatol 139: 928–930, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daram SR, Cortese CM, Bastani B: Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Report of a new case with literature review. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 754–759, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grobner T: Gadolinium—A specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1104–1108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Dupont A, Damholt MB, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2359–2362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy associated with exposure to gadolinium-containing contrast agents—St. Louis, Missouri, 2002–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 56: 137–141, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collidge TA, Thomson PC, Mark PB, Traynor JP, Jardine AG, Morris ST, Simpson K, Roditi GH: Gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Retrospective study of a renal replacement therapy cohort. Radiology 245: 168–175, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A population study examining the relationship of disease development to gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2: 264–267, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Othersen JB, Maize JC, Woolson RF, Budisavljevic MN: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to gadolinium in patients with renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 3179–3185, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J: Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Predictor of early mortality and association with gadolinium exposure. Arthritis Rheum 56: 3433–3441, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kallen AJ, Jhung MA, Cheng S, Hess T, Turabelidze G, Abramova L, Arduino M, Guarner J, Pollack B, Saab G, Patel PR: Gadolinium-containing magnetic resonance imaging contrast and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A case-control study. Am J Kidney Dis, 51: 966–975, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal R, Brunelli SM, Williams K, Mitchell MD, Feldman HI, Umscheid CA: Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 24: 856–863, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA alert: Information for healthcare professionals gadolinium-based contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (marketed as Magnevist, MultiHance, Omniscan, OptiMARK, ProHance). May 23, 2007. Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm142884.htm Accessed September 4, 2009

- 18. Perazella MA: Advanced kidney disease, gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: The perfect storm. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 519–525, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perazella MA: Current status of gadolinium toxicity in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 461–469, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kribben A, Witzke O, Hillen U, Barkhausen J, Daul AE, Erbel R: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1621–1628, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weinreb JC, Kuo PH: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 17: 159–167, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yerram P, Saab G, Karuparthi PR, Hayden MR, Khanna R: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A mysterious disease in patients with renal failure—Role of gadolinium-based contrast media in causation and the beneficial effect of intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 258–263, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lind-Ramskov K, Thomsen HS: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and contrast medium-induced nephropathy: A choice between the devil and the deep blue sea for patients with reduced renal function? Acta Radiol 50: 1–3, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perez-Rodriguez J, Lai S, Ehst BD, Fine DM, Bluemke DA: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Incidence, associations, and effect of risk factor assessment—Report of 33 cases. Radiology 250: 371–377, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Juluru K, Vogel-Claussen J, Macura KJ, Kamel IR, Steever A, Bluemke DA: MR imaging in patients at risk for developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Protocols, practices, and imaging techniques to maximize patient safety. Radiographics 29: 9–22, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weinreb JC: Impact on hospital policy: Yale experience. J Am Coll Radiol, 5: 53–56, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cowper SE: Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy 2001–2009. Available at http://www.icnfdr.org Accessed September 4, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28. Martin DR: Nephrogenic system fibrosis: A radiologist's practical perspective. Eur J Radiol 66: 220–224, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sieber MA, Lengsfeld P, Walter J, Schirmer H, Frenzel T, Siegmund F, Weinmann HJ, Pietsch H: Gadolinium-based contrast agents and their potential role in the pathogenesis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: The role of excess ligand. J Magn Reson Imaging 27: 955–962, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sieber MA, Lengsfeld P, Frenzel T, Golfier S, Schmitt-Willich H, Siegmund F, Walter J, Weinmann HJ, Pietsch H: Preclinical investigation to compare different gadolinium-based contrast agents regarding their propensity to release gadolinium in vivo and to trigger nephrogenic systemic fibrosis-like lesions. Eur Radiol 18: 2164–2173, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Broome DR: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis associated with gadolinium based contrast agents: A summary of the medical literature reporting. Eur J Radiol 66: 230–234, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reilly RF: Risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with gadoteridol (ProHance) in patients who are on long-term hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 747–751, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomsen HS: How to avoid nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Current guidelines in Europe and the United States. Radiol Clin North Am 47: 871–875, vii, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gadolinium-based contrast agents & nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: FDA Briefing Document. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/DrugSafetyandRiskManagement-AdvisoryCommittee/UCM190850.pdf Accessed January 4, 2010

- 35. Richwine L: US panel sees higher skin risk with some MRI drugs. Available at http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSN0813180520091209 Accessed January 4, 2010

- 36. Kuo PH: Gadolinium-containing MRI contrast agents: Important variations on a theme for NSF. J Am Coll Radiol 5: 29–35, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wertman R, Altun E, Martin DR, Mitchell DG, Leyendecker JR, O'Malley RB, Parsons DJ, Fuller ER, III, Semelka RC: Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Evaluation of gadolinium chelate contrast agents at four American universities. Radiology 248: 799–806, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saab G, Abu-Alfa A: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis—Implications for nephrologists. Eur J Radiol 66: 208–212, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sadowski EA, Bennett LK, Chan MR, Wentland AL, Garrett AL, Garrett RW, Djamali A: Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Risk factors and incidence estimation. Radiology 243: 148–157, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J, Cohen EP, Collins AJ, Eckardt KU, Nahas ME, Jaber BL, Jadoul M, Levin A, Powe NR, Rossert J, Wheeler DC, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: Approaches and initiatives—A position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int 72: 247–259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]