Introduction

Vitamin D is an inactive precursor, requiring two hydroxylation steps, first in the liver and then the kidney, to be converted to 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol), the active hormone. The details of this metabolic conversion are described in other chapters in this volume. Calcitriol then binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) to mediate the actions of the hormone. As also detailed in other sections of this volume, calcitriol/VDR complexes regulate multiple target genes throughout the body. Most obvious are genes that regulate calcium and phosphate metabolism and that are responsible for normal mineralization of bone. In the absence of either the active hormone (calcitriol) or a functional receptor (VDR), calcium absorption is impaired and bones are become inadequately mineralized. When this occurs in children, the disease rickets develops, when it happens in adults, osteomalacia develops. The most common cause of rickets and osteomalacia is vitamin D deficiency that is described in chapter 5 for children and chapter 6 for adults.

However, two very interesting and rare genetic diseases can also cause rickets in children. These diseases, and the knockout mouse models of the two human diseases, have provided exceptional insight into the metabolism and mechanism of action of calcitriol. The critical enzyme to synthesize calcitriol from 25(OH)D, the circulating hormone precursor, is 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase). When this enzyme is defective and calcitriol can no longer be synthesized, the disease 1α-hydroxylase deficiency develops. The disease is also known as vitamin D dependent rickets type 1 (VDDR-1) or pseudovitamin D deficiency rickets (PDDR). When the VDR is defective, the disease hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets (HVDRR) also known as vitamin D dependent rickets type II (VDDR II) develops. Both diseases are rare autosomal recessive disorders characterized by hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism and early onset severe rickets. As will be discussed below in more detail, a crucial difference between the two diseases is that 1α-hydroxylase deficiency is characterized by extremely low to absent serum calcitriol levels while HVDRR, characteristic of a target organ resistance disease, is distinguished by exceedingly high levels of calcitriol. In this chapter, we will discuss and compare these two genetic childhood diseases that present similarly with hypocalcemia and rickets in infancy. However, our focus will be on HVDRR that we consider a more complex and serious disease since affected children do not usually respond to treatment with calcitriol while 1α-hydroxylase deficiency does.

1α-Hydroxylase Deficiency in Children

In 1973 Fraser et al [19] postulated that VDDR I was an inborn error of vitamin D metabolism involving defective conversion of 25(OH)D to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Approximately 25 years later in 1997 the gene (CYP27B1) encoding the 1α-hydroxylase enzyme was cloned by several groups [20,51,58,60,61] and it was immediately demonstrated that VDDR-I was caused by mutations in the CYP27B1 gene [20].

Children with the disease 1α-hydroxylase deficiency present with a clinical picture of joint pain and deformity, hypotonia, muscle weakness, growth failure and sometimes hypocalcemic seizures or fractures in early infancy [4,21,47]. Laboratory analysis reveals hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, elevated alkaline phosphatase and low or undetectable calcitriol in the presence of adequate 25(OH)D levels (Table 1). X-ray findings show characteristic changes of rickets. The children have no clinical response to high doses of cholecalciferol but respond to physiologic doses of calcitriol or 1α-hydroxyvitamin D [15]. Although it is a rare inborn error, 1α-hydroxylase deficiency is more frequently found in the French Canadian population [14].

Table 1.

Comparison of genetic defect in vitamin D action

| 1α-hydroxylase deficiency | HVDRR | |

|---|---|---|

| Gene | CYP27B1 | VDR |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | low | high |

| PTH | high | high |

| Calcium | low | low |

| Phosphate | low | low |

| Alopecia | no | yes |

| Response to calcitriol | yes | no |

Mutations in the CYP27B1 Gene as the Molecular Basis for 1α-Hydroxylase Deficiency

VDDRI is due to heterogeneous mutations in the CYP27B1 gene that abolish or reduce 1α-hydroxylase enzymatic activity. A recent review by the Miller and Portale group [31] catalogs the multiple different mutations in the CYP27B1 gene that have been described including missense mutations, deletions, duplications, and splice site changes. To date, 48 patients have been described with mutations in CYP27B1 gene including both genders of children from multiple ethnic backgrounds often in the setting of consanguinity.

The 1α-hydroxylase is a Type I mitochondrial P450 enzyme that functions as an oxidase. The reaction utilizes electrons from reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and molecular oxygen. The P450 moiety binds the 25(OH)D substrate, receives electrons and molecular oxygen and catalyzes the reaction using the heme group iron to coordinate oxygen [31,50]. Deletions, premature termination due to splice site mutations and insertions are the commonest defects that disrupt or eliminate the heme-binding domain and thereby inactivate the enzyme [31]. In some cases of 1α-hydroxylase deficiency, missense mutations have been identified in the CYP27B1 gene that disrupt α helical structures, the meander sequence, the cysteine pocket that binds the heme group and the substrate recognition sites (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Missense mutations identified in patients with 1α-hydroxylase deficiency. The human 1α-hydroxylase enzyme is composed of 508 amino acids. The locations of the missense mutations are shown above the line. Depicted below line are the names of the α helices (open boxes), the meander sequence (M, grey box); the cysteine pocket (CP, hatched box); substrate recognition sites (SRS, black boxes) and the β turns.

The major site in the body of 1α-hydroxylase activity is the kidney. It is of interest that 1α-hydroxylase is also expressed in many tissues of the body including breast, prostate, colon, placenta and macrophages [25]. These regions of local production are hypothesized to be of considerable importance for the expanded role of calcitriol in reducing cancer risk, fighting infection, and mediating anti- inflammatory actions, etc. However, it is the renal enzyme that determines the circulating 1α,25(OH)2D3 concentration. The renal enzyme is under careful regulation by parathyroid hormone, calcium status and calcitriol levels so that calcium homeostasis is tightly controlled by complex feedback loops.

The children with 1α-hydroxylase deficiency due to mutations in the CYP27B1 gene present for medical attention with metabolic abnormalities in early infancy usually prior to two years of age. In utero development is considered to be normal due to maternal normocalcemia. When the infants come to medical attention they characteristically show growth retardation, bone and joint deformities and bone pain. Teeth may show marked hypoplasia of the enamel. Serum levels show hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism and elevated alkaline phosphatase. X-rays exhibit classical features of rickets. Since the availability of 1α-hydroxylated vitamin D metabolites such as calcitriol or 1α-hydroxyvitamin D, therapeutic responses and complete remission of the disease can be routinely achieved. Doses of calcitriol of 1–3 μg/day are adequate to heal the rickets and return serum chemistries to normal. Calcium levels improve within days and radiologic improvement in bones can be seen within 2–3 months. Documentation of healing of rickets has been noted in 9–10 months [15].

Mouse Models of 1α-Hydroxylase Deficiency

Several groups have developed mouse models of 1α-hydroxylase deficiency using targeted disruption of the CYP27B1 gene [13,54]. The targeted region of the gene has been the hormone binding and heme binding domains of the protein. After weaning, the 1α-hydroxylase null mice develop the classical features of human 1α-hydroxylase deficiency with hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, retarded growth and skeletal changes of rickets. Many of the non-skeletal changes seen including reproductive and immune function abnormalities were probably at least partly due to severe hypocalcemia. It was subsequently discovered that feeding the mice a “rescue” diet high in calcium, phosphorous and lactose could normalize the hypocalcemia present in these mice as well as the VDR null mice and appear to heal the rickets [2,33]. The Goltzman group went on to compare findings in 1α-hydroxylase null mice with VDR null mice and the double mutant that combines disruption of both 1α-hydroxylase and VDR [22,53]. In addition, the authors studied the effects of normalizing calcium homeostasis with the rescue diet and treatment with calcitriol. They concluded that normalization of calcium cannot entirely substitute for vitamin D action in skeletal and mineral homeostasis and that the two agents have discrete and overlapping functions. Both are required to maintain normal osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone formation. The widened cartilaginous growth plates characteristic of rickets could only be completely normalized by a combination of calcium and 1,25(OH)2D3. These issues will be further discussed below when HVDRR and VDR mutations are discussed.

Hereditary Vitamin D Resistant Rickets in Children

Children with HVDRR develop hypocalcemia and severe rickets usually within months of birth. Affected children have bone pain, muscle weakness, hypotonia and occasionally have convulsions due to the hypocalcemia. They are often growth retarded and in some cases develop severe dental caries or exhibit hypoplasia of the teeth [41,42]. The laboratory findings include low serum concentrations of calcium and phosphate and elevated serum alkaline phosphatase activity. The children exhibit secondary hyperparathyroidism with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. The serum 25(OH)D values are usually normal and the 1,25(OH)2D levels are substantially elevated. This clinical finding distinguishes HVDRR from 1α-hydroxylase deficiency in which the serum 1,25(OH)2D values are low or absent (Table 1). Many children with HVDRR also have sparse body hair and some have total scalp and body alopecia including eyebrows and in some cases eyelashes. This feature also helps distinguish HVDRR from 1α-hydroxylase deficiency. Most affected children are resistant to therapy with supra-physiologic doses of all forms of vitamin D including calcitriol.

HVDRR is an autosomal recessive disease with males and females equally affected. The parents of patients, who are heterozygous carriers of the genetic trait, usually show no symptoms of the disease and have normal bone development. These findings indicate that a single defective allele is not sufficient to cause disease. In most cases, consanguinity is associated with the disease with each parent contributing a defective gene.

Mutations in the VDR gene as the Molecular Basis for Hereditary Vitamin D Resistant Rickets

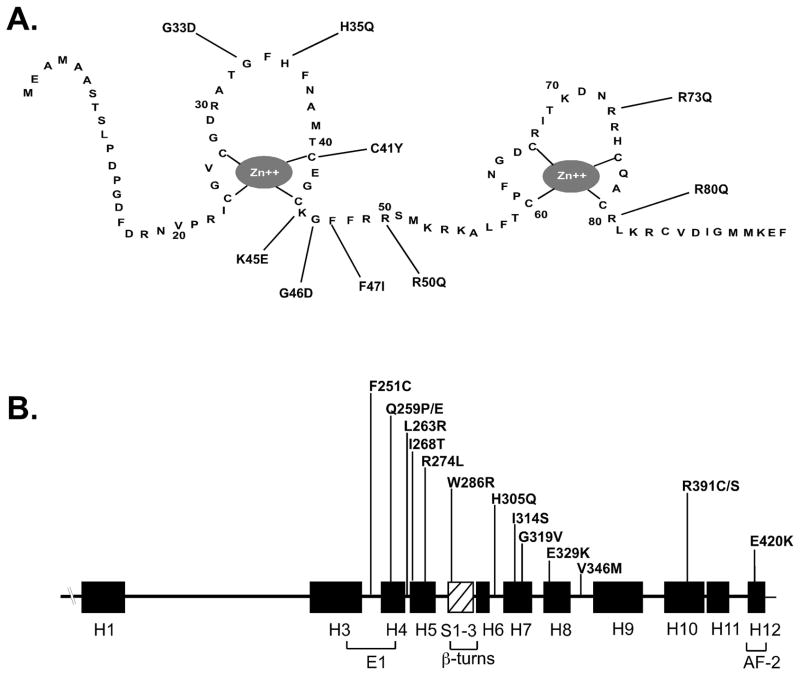

Over 100 cases of HVDRR have been recorded and a number of these have been analyzed at the biochemical and molecular level [39,41,42]. Presently, 34 heterogeneous mutations have been identified in the VDR gene as the cause of HVDRR (Fig. 2). Mutations in the DNA binding domain (DBD) prevent the VDR from binding to DNA causing total 1,25(OH)2D3 resistance even though 1,25(OH)2D3 binding to the VDR is normal. On the other hand, mutations in the ligand binding domain (LBD) may disrupt ligand binding, or heterodimerization with RXR, or prevent coactivators from binding to the VDR and cause partial or total hormone resistance. Other mutations that have been identified in the VDR that cause 1,25(OH)2D3 resistance include nonsense mutations, insertions/substitutions, insertions/duplications, deletions, and splice site mutations. Some of these VDR mutations will be described below.

Fig. 2.

Missense mutations identified in patients with HVDRR. (A) The locations of missense mutations in the VDR DNA binding-domain depicted as a two-zinc finger structure. (B) The locations of the missense mutations in the VDR ligand-binding domain are shown above the line. The filled rectangles represent α helices (H1–H12) and the hatched box represents the β sheet structure. The location of the E1 and AF-2 domains are also indicated.

To date, nine missense mutations have been identified in the VDR DBD as the cause of HVDRR (Fig. 2A). These mutant VDRs exhibit normal ligand binding but defective DNA binding [41,42]. A common feature of patients with mutations in the DBD is that they all have alopecia. The heterozygotic parents with a single mutant allele are asymptomatic.

Several nonsense mutations have been identified in the VDR gene that truncate the VDR protein [41,42]. Fibroblasts from patients with VDR nonsense mutations exhibit no ligand binding and often the truncated VDR protein could not be detected by immunoblotting. One particular mutation, a single base change in exon 8 that introduced a premature termination codon (Y295X), was identified in several families that comprise a large kindred where consanguineous marriages were common [40]. The VDR mRNA was undetectable by northern blot analysis indicating that the Y295X mutation led to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Interestingly, in one family with an R30X mutation, the parents of the affected child had somewhat elevated serum 1,25(OH)2D levels indicating some resistance to 1,25(OH)2D [48]. All of the affected children with nonsense mutations had alopecia.

Splice site mutations in the VDR gene have also been identified as the cause of HVDRR. These mutations usually cause a frameshift and eventually introduce a downstream premature stop signal resulting in a non-functional VDR. Splice site mutations in the VDR gene cause exons to be skipped [23,35] or cause incorporation of an intron into the VDR mRNA [30]. In one case, a cryptic 5′ donor splice site was generated in exon 6 that deleted 56 nucleotide bases and led to a frameshift in exon 7 [12].

To date, 15 missense mutations have been identified in the VDR LBD (Fig. 2) [56,66]. One patient had an R274L mutation that altered the contact point for the 1α-hydroxyl group of 1,25(OH)2D3 [55,56]. The mutation lowered the binding affinity of the VDR for 1,25(OH)2D3. A second patient had an H305Q mutation that altered the contact point for the 25-hydroxyl group of 1,25(OH)2D3 [37,55]. This mutation also lowered the binding affinity of the VDR for 1,25(OH)2D3. These cases illustrate the importance of critical amino acids as contact points for 1,25(OH)2D3 and demonstrate that mutations of these residues can be the basis for HVDRR.

Mutations have also been identified in the VDR that disrupt VDR:RXR protein interaction as a cause HVDRR. For example, an R391C mutation in the VDR LBD had no affect on ligand binding but reduced its transactivation activity. R391 is located in helix H10 where the RXR dimer interface is formed from helix H9 and helix H10 and the interhelical loops between H7-H8 and H8-H9 in VDR [55]. R391 was also mutated to serine (R391S) [52]. Several other mutations have been identified in the VDR that affect RXR heterodimerization including Q259P and F251C [12,46]. Q259 was also mutated to glutamic acid (Q259E) [36]. A V346M mutation was identified in a patient with HVDRR and may be important in RXR heterodimerization [3]. All of the patients with defects in RXR heterodimerization had alopecia.

A mutation has also been identified in the VDR that prevented coactivator recruitment that is critical for transcriptional activity [45]. An E420K mutation located in helix H12 had no affect on ligand binding, VDR-RXR heterodimerization or DNA-binding. However, the E420K mutation abolished binding by the coactivators SRC-1 and DRIP205. Interestingly, the child with the E420K mutation did not have alopecia [45] suggesting that ligand-mediated transactivation and coactivator recruitment by the VDR is not required for hair growth.

Several compound heterozygous mutations in the VDR gene have been identified in children with HVDRR. In these cases each heterozygotic parent harbored a different mutant VDR and consanguinity was not involved. One patient was heterozygous for an E329K mutation and also had a second mutation on the other allele that deleted a single nucleotide 366 (366delC) in exon 4 [49]. The single base deletion resulted in a frameshift creating a premature termination signal that truncated most of the LBD. The E329K mutation in helix H8 that is important in heterodimerization with RXR and likely disrupts this activity. L263R and R391S compound heterozygous mutations were also identified in the VDR gene in a child with HVDRR and early childhood-onset type 1 diabetes [52]. The mutant VDRs in this case exhibited differential effects on 24-hydroxylase and RelB promoters. The 24-hydroxylase responses were abolished in the L263R mutant but only partially altered in the R391S mutant. On the other hand, RelB responses were normal for the L263R mutant but the R391S mutant was defective in this response [52]. The reason for the differential activities of these VDR mutants is unknown. Compound heterozygous mutations were also found in the VDR gene in a patient with HVDRR and alopecia [69]. The patient was heterozygous for a nonsense mutation R30X and a 3 bp deletion in exon 6 that deleted the codon for lysine at amino acid 246 (3K246). The 3K246 mutation did not affect ligand binding but abolished heterodimerization with RXR and binding to coactivators [69]. All of the patients with compound heterozygous mutations had alopecia.

Two cases of insertions/duplications in the VDR gene causing HVDRR have been reported. In one case a unique 5-bp deletion/8-bp insertion was found in the VDR gene [44]. The mutation deleted amino acids H141 and Y142 and inserted three amino acids (L141, W142, and A143). Only the A143 insertion into the WT VDR disrupted transactivation to the same extent as the natural mutation. The patient with this mutation did not have alopecia. In the second case a 102 bp insertion/duplication was found in the VDR gene that introduced a premature stop (Y401X) and deleted helix H12 [43]. The truncated VDR was able to heterodimerize with RXR, bind to DNA and interact with the corepressor hairless (HR) but failed to bind coactivators and was transactivation defective. The patient with this mutation had patchy alopecia.

There is only a single reported case where investigators failed to detect a mutation in the VDR as the basis of HVDRR [24]. In this case the authors speculated that the resistance to the action of 1,25(OH)2D3 was due to abnormal expression of hormone response element-binding proteins belonging to the hnRNP family that prevented the VDR-RXR complex from binding to vitamin D response elements in target genes [10].

Mouse Models of HVDRR

Mouse models of HVDRR have been created by targeted ablation of the VDR [34,68]. The targeted region has been the DBD domain. The VDR null mice (VDRKO) recapitulate the findings in the children with HVDRR. The VDRKO mice appear normal at birth and become hypocalcemic and their parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels increase sometime after weaning. Bone mineralization is severely impaired and the changes of rickets develop over time. The VDRKO mice have normal hair at birth but develop progressive alopecia, thickened skin, enlarged sebaceous glands and epidermal cysts [34,68]. In one VDRKO mouse model uterine hypoplasia with impaired folliculogenesis was found in female reproductive organs [68]. When the VDRKO mice are fed a “rescue” diet, their calcium can be normalized and the rickets reversed or prevented as was described for children with HVDRR successfully treated with intravenous or oral calcium. Many non-skeletal abnormalities seen in the hypocalcemic mice are prevented by the rescue diet indicating the abnormalities resulted from the hypocalcemia and were not directly caused by the absence of a functional VDR. However, again as in children with HVDRR, the alopecia is not reversed or prevented by normalization of calcium homeostasis.

Therapy of HVDRR

Mutations in the VDR that cause HVDRR result in partial or total resistance to 1,25(OH)2D3 action. The patients become hypocalcemic predominately because of a lack of VDR signaling in the intestine to promote calcium absorption. The hypocalcemia leads to a decrease in bone mineralization and causes rickets. Some HVDRR patients improve both clinically and radiologically when treated with pharmacological doses of vitamin D ranging from 5000 to 40,000 IU/day; 20 to 200 μg/day of 25(OH)D3; and 17–20 μg/day of 1,25(OH)2D3 [41,42]. Some patients also responded to 1αOH)D3 [41,42]. The patient with the H305Q mutation, a contact point for the 25-hydroxyl group of 1,25(OH)2D3, showed improvement with 12.5 μg/day calcitriol treatment [37,63]. On the other hand, the patient with the R274L mutation, a contact point for the 1α-hydroxyl group of 1,25(OH)2D3, was unresponsive to treatment with 600,000 IU vitamin D; up to 24 μg/day of 1,25(OH)2D3; or 12 μg/day 1 α(OH)D3 [18].

When patients fail to respond to vitamin D or 1,25(OH)2D3, intensive calcium therapy is used. Oral calcium can be absorbed in the intestine by both vitamin D-dependent and vitamin D-independent pathways. In children with non-functional VDR, the vitamin D-independent pathway becomes critical. When oral calcium therapy is successful, the calcium levels in the gut have been raised high enough so that passive diffusion or other non-vitamin D dependent absorption is adequate to maintain normocalcemia. IV calcium infusions are used to treat children with HVDRR who failed prior treatments with large doses of vitamin D derivatives and/or oral calcium [5,6,8,28,65]. Intravenous calcium therapy bypasses the calcium absorption defect in the intestine caused by the lack of action of the mutant VDR. However, in affected children receiving IV calcium, when the IV therapy is discontinued the syndrome recurs slowly over time. Some children have been managed with intermittent IV calcium regimens using oral calcium in the intervals [35]. Once the child is older, perhaps when the skeleton has finished major growth, oral calcium often suffices to maintain normocalcemia and the IV calcium regimen can be discontinued [28]. Oral calcium alone has sometimes been successfully used as a therapy for HVDRR patients [57]. Spontaneous healing of rickets has been observed in some HVDRR patients as they get older and all therapy sometimes can be discontinued [11,26,27]. In all of the cases regardless of the therapy, if alopecia is present, it is unchanged by the treatment despite normalization of calcium and healing of rickets.

A most unexpected finding is that raising the serum calcium to normal by IV or oral calcium administration reversed all aspects of HVDRR including hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, rickets, elevated alkaline phosphatase, etc. except for alopecia (discussed below). Correcting the hypocalcemia often corrects the hypophosphatemia without the need for phosphate supplements. This finding indicates that the low phosphate was caused by the secondary hyperparathyroidism which normalizes with correction of the hypocalcemia even in the absence of VDR action. The inescapable conclusion is that the most important actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 on calcium and bone homeostasis occur in the intestine on calcium absorption and not in the bone. The ability of the rachitic bone abnormality to normalize in the absence of VDR-mediated vitamin D action was surprising. The data are incomplete in patients about whether the bones are entirely normal and Panda et al., using VDR knockout mice, has data suggesting that subtle defects remain in the bones of VDR null mice whose serum calcium had been corrected by a rescue diet [53]. However, the reversal of all clinical aspects of HVDRR with IV calcium does indicate that healing of bone and reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hypophosphatemia can take place without normal VDR-mediated vitamin D action. There is no doubt that vitamin D has important actions on bone and parathyroid cells. However, these actions can apparently be compensated for in vivo if the calcium level is normalized.

In recent years there have been many new actions attributed to vitamin D that mediate important and wide-spread effects that are unrelated to calcium and bone homeostasis [16,17]. These include actions to reduce the risk of cancer, autoimmune disease, infection, neurodegeneration, etc. At this time we have not detected a trend toward an increased risk for any of these potential problems in the children with HVDRR. However, there are very few cases of HVDRR and most of the cases are detected in infants and young children so that it may be too early in their life to detect an increased tendency toward any of these potential health problems.

Alopecia

The molecular analysis of the VDR from HVDRR patients with and without alopecia has provided several clues to the functions of the VDR that are important for hair growth. For example, patients with premature stop mutations and VDR knockout mice have alopecia indicating that the intact VDR protein is critical for renewed hair growth after birth [34,68]. Expression of the WT VDR in keratinocytes of VDR knockout mice prevented alopecia, a finding that further supports a role for the VDR in regulating hair growth [9]. Patients with DBD mutations also have alopecia indicating that VDR binding to DNA is critical to prevent alopecia. Patients with VDR mutations that inhibit RXR heterodimerization have alopecia indicating an essential role for VDR-RXR heterodimers in hair growth [12,46,66]. Also, inactivation of RXRα in keratinocytes in mice also caused alopecia clearly demonstrating a role for RXR in hair growth [32].

On the other hand, patients with VDR mutations that abolish ligand binding or patients with 1α-hydroxylase deficiency and other forms of vitamin D deficiency do not have alopecia suggesting that a ligand-independent action of the VDR is critical to regulate the normal hair cycle [29,38,45,59]. The patient with the E420K mutation that abolished coactivator binding (but not ligand binding or RXR heterodimerization) did not have alopecia indicating that VDR actions to regulate hair growth were independent of coactivator interactions [81]. Also, when ligand-binding defective or coactivator-binding defective mutant VDRs were specifically expressed in keratinocytes in VDR knockout mice that have alopecia, hair growth was fully or partially restored [59].

The alopecia associated with HVDRR is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from the generalized disease atrichia with papular lesions (APL) found in patients with mutations in the hairless (hr) gene [1,49,64]. The hr gene product, HR acts as a corepressor and directly interacts with the VDR and suppresses 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transactivation [29,64,67]. It has been hypothesized that the role of the VDR in the hair cycle is to repress the expression of a gene(s) in a ligand-independent manner [29,45,59,64]. The ligand-independent activity requires that the VDR heterodimerize with RXR and bind to DNA [38,45]. The corepressor actions of HR may also be required in order for the unliganded VDR to repress gene transcription during the hair cycle. Mutations in the VDR that disrupt the ability of the unliganded VDR to suppress gene transcription are hypothesized to lead to the derepression of a gene(s) whose product, when expressed inappropriately, disrupts the hair cycle that ultimately leads to alopecia [29,45,59,64]. Inhibitors of the Wnt signaling pathway are possible candidates [7,62]. Thus far, there have been no reports of mutations in the VDR that affect interactions with HR. The role of HR in regulating the unliganded action of the VDR during the hair cycle remains to be discovered.

Conclusions

The biochemical and genetic analysis of the VDR in HVDRR patients has yielded important insights into the structure and function of the receptor in mediating 1,25(OH)2D3 action. Similarly, study of the affected children with HVDRR continues to provide a more complete understanding of the biological role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vivo. A concerted investigative approach to HVDRR at the clinical, cellular and molecular level has proven exceedingly valuable in gaining knowledge of the functions of the domains of the VDR and elucidating the detailed mechanism of action of 1,25(OH)2D3. These studies have been essential to promote the wellbeing of the families with HVDRR and in improving the diagnostic and clinical management of this rare genetic disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. DK042482 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahmad W, Faiyaz ul Haque M, Brancolini V, et al. Alopecia universalis associated with a mutation in the human hairless gene. Science. 1998;279:720–24. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amling M, Priemel M, Holzmann T, et al. Rescue of the skeletal phenotype of vitamin D receptor-ablated mice in the setting of normal mineral ion homeostasis: formal histomorphometric and biomechanical analyses. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4982–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arita K, Nanda A, Wessagowit V, et al. A novel mutation in the VDR gene in hereditary vitamin D-resistant rickets. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:168–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnaud C, Maijer R, Reade T, et al. Vitamin D dependency: an inherited postnatal syndrome with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Pediatrics. 1970;46:871–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balsan S, Garabedian M, Larchet M, et al. Long-term nocturnal calcium infusions can cure rickets and promote normal mineralization in hereditary resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1661–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI112483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balsan S, Garabedian M, Liberman UA, et al. Rickets and alopecia with resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: two different clinical courses with two different cellular defects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:803–11. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-4-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaudoin GM, 3rd, Sisk JM, Coulombe PA, et al. Hairless triggers reactivation of hair growth by promoting Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14653–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507609102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bliziotes M, Yergey AL, Nanes MS, et al. Absent intestinal response to calciferols in hereditary resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: documentation and effective therapy with high dose intravenous calcium infusions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:294–300. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-2-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CH, Sakai Y, Demay MB. Targeting expression of the human vitamin D receptor to the keratinocytes of vitamin D receptor null mice prevents alopecia. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5386–89. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Hewison M, Hu B, et al. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) binding to hormone response elements: A cause of vitamin D resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6109–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031395100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen TL, Hirst MA, Cone CM, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D resistance, rickets, and alopecia: analysis of receptors and bioresponse in cultured fibroblasts from patients and parents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59:383–88. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-3-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockerill FJ, Hawa NS, Yousaf N, et al. Mutations in the vitamin D receptor gene in three kindreds associated with hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3156–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.9.4243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dardenne O, Prud’homme J, Arabian A, et al. Targeted inactivation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3)-1(alpha)-hydroxylase gene (CYP27B1) creates an animal model of pseudovitamin D-deficiency rickets. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3135–41. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Braekeleer M, Larochelle J. Population genetics of vitamin D-dependent rickets in northeastern Quebec. Ann Hum Genet. 1991;55:283–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1991.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delvin EE, Glorieux FH, Marie PJ, et al. Vitamin D dependency: replacement therapy with calcitriol? J Pediatr. 1981;99:26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80952-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman D, Malloy PJ, Krishnan AV, et al. Vitamin D: biology, action, and clinical implications. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, et al., editors. Osteoporosis. 3. San Diego: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 317–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH, editors. Vitamin D. 2. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. p. 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraher LJ, Karmali R, Hinde FR, et al. Vitamin D-dependent rickets type II: extreme end organ resistance to 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 in a patient without alopecia. Eur J Pediatr. 1986;145:389–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00439245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser D, Kooh SW, Kind HP, et al. Pathogenesis of hereditary vitamin-D-dependent rickets. An inborn error of vitamin D metabolism involving defective conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:817–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197310182891601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu GK, Lin D, Zhang MY, et al. Cloning of human 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1 alpha-hydroxylase and mutations causing vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1961–70. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glorieux FH, St-Arnaud R. Vitamin D pseudodeficiency. In: Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH, editors. Vitamin D. 2. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. pp. 1197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goltzman D, Miao D, Panda DK, et al. Effects of calcium and of the Vitamin D system on skeletal and calcium homeostasis: lessons from genetic models. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:485–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawa NS, Cockerill FJ, Vadher S, et al. Identification of a novel mutation in hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets causing exon skipping. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hewison M, Rut AR, Kristjansson K, et al. Tissue resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D without a mutation of the vitamin D receptor gene. Clin Endocrinol. 1993;39:663–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewison M, Zehnder D, Chakraverty R, et al. Vitamin D and barrier function: a novel role for extra-renal 1 alpha-hydroxylase. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirst MA, Hochman HI, Feldman D. Vitamin D resistance and alopecia: a kindred with normal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D binding, but decreased receptor affinity for deoxyribonucleic acid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:490–95. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-3-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochberg Z, Benderli A, Levy J, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D resistance, rickets, and alopecia. Am J Med. 1984;77:805–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochberg Z, Tiosano D, Even L. Calcium therapy for calcitriol-resistant rickets. J Pediatr. 1992;121:803–08. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81919-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh JC, Sisk JM, Jurutka PW, et al. Physical and functional interaction between the vitamin D receptor and hairless corepressor, two proteins required for hair cycling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38665–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katavetin P, Wacharasindhu S, Shotelersuk V. A girl with a novel splice site mutation in VDR supports the role of a ligand-independent VDR function on hair cycling. Horm Res. 2006;66:273–76. doi: 10.1159/000095546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim CJ, Kaplan LE, Perwad F, et al. Vitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase gene mutations in patients with 1alpha-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3177–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M, Chiba H, Warot X, et al. RXR-alpha ablation in skin keratinocytes results in alopecia and epidermal alterations. Development. 2001;128:675–88. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li YC, Amling M, Pirro AE, et al. Normalization of mineral ion homeostasis by dietary means prevents hyperparathyroidism, rickets, and osteomalacia, but not alopecia in vitamin D receptor-ablated mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4391–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, et al. Targeted ablation of the vitamin D receptor: an animal model of vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9831–35. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma NS, Malloy PJ, Pitukcheewanont P, et al. Hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets: Identification of a novel splice site mutation in the vitamin D receptor gene and successful treatment with oral calcium therapy. Bone. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macedo LC, Soardi FC, Ananias N, et al. Mutations in the vitamin D receptor gene in four patients with hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;52:1244–51. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302008000800007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malloy PJ, Eccleshall TR, Gross C, et al. Hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets caused by a novel mutation in the vitamin D receptor that results in decreased affinity for hormone and cellular hyporesponsiveness. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:297–304. doi: 10.1172/JCI119158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Hereditary 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets. Endocr Dev. 2003;6:175–99. doi: 10.1159/000072776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Molecular defects in the vitamin D receptor associated with hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D resistant rickets. In: Holick MF, editor. Vitamin D: physiology, molecular biology, and clinical applications. Totowa: Humana Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malloy PJ, Hochberg Z, Tiosano D, et al. The molecular basis of hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 resistant rickets in seven related families. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:2071–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI114944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malloy PJ, Pike JW, Feldman D. Hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D resistant rickets. In: Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux F, editors. Vitamin D. 2. San Diego: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1207–38. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malloy PJ, Pike JW, Feldman D. The vitamin D receptor and the syndrome of hereditary 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:156–88. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malloy PJ, Wang J, Peng L, et al. A unique insertion/duplication in the VDR gene that truncates the VDR causing hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets without alopecia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:285–92. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malloy PJ, Xu R, Cattani A, et al. A unique insertion/substitution in helix H1 of the vitamin D receptor ligand binding domain in a patient with hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1018–24. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2004.19.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malloy PJ, Xu R, Peng L, et al. A novel mutation in helix 12 of the vitamin D receptor impairs coactivator interaction and causes hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets without alopecia. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2538–46. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malloy PJ, Zhu W, Zhao XY, et al. A novel inborn error in the ligand-binding domain of the vitamin D receptor causes hereditary vitamin D-resistant rickets. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;73:138–48. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marx SJ, Spiegel AM, Brown EM, et al. A familial syndrome of decrease in sensitivity to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47:1303–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-6-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mechica JB, Leite MO, Mendonca BB, et al. A novel nonsense mutation in the first zinc finger of the vitamin D receptor causing hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-resistant rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3892–94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller J, Djabali K, Chen T, et al. Atrichia caused by mutations in the vitamin D receptor gene is a phenocopy of generalized atrichia caused by mutations in the hairless gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:612–17. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller WL. Minireview: regulation of steroidogenesis by electron transfer. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2544–50. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monkawa T, Yoshida T, Wakino S, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNA and genomic DNA for human 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1 alpha-hydroxylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:527–33. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen M, d’Alesio A, Pascussi JM, et al. Vitamin D-resistant rickets and type 1 diabetes in a child with compound heterozygous mutations of the vitamin D receptor (L263R and R391S): dissociated responses of the CYP-24 and rel-B promoters to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:886–94. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panda DK, Miao D, Bolivar I, et al. Inactivation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase and vitamin D receptor demonstrates independent and interdependent effects of calcium and vitamin D on skeletal and mineral homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16754–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panda DK, Miao D, Tremblay ML, et al. Targeted ablation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1alpha -hydroxylase enzyme: evidence for skeletal, reproductive, and immune dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7498–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131029498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rochel N, Wurtz JM, Mitschler A, et al. The crystal structure of the nuclear receptor for vitamin D bound to its natural ligand. Mol Cell. 2000;5:173–79. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rut AR, Hewison M, Rowe P, et al. A novel mutation in the steroid binding region of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene in hereditary vitamin D resistant rickets (HVDRR) In: Norman AW, Bouillon R, Thomasset M, editors. Vitamin D: gene regulation, structure-function analysis, and clinical application Eighth workshop on vitamin D. New York: Walter de Gruyter; 1991. pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakati N, Woodhouse NJY, Niles N, et al. Hereditary resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: clinical and radiological improvement during high-dose oral calcium therapy. Hormone Res. 1986;24:280–87. doi: 10.1159/000180568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shinki T, Shimada H, Wakino S, et al. Cloning and expression of rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3- 1alpha-hydroxylase cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12920–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skorija K, Cox M, Sisk JM, et al. Ligand-independent actions of the vitamin D receptor maintain hair follicle homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:855–62. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.St-Arnaud R, Messerlian S, Moir JM, et al. The 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-alpha-hydroxylase gene maps to the pseudovitamin D-deficiency rickets (PDDR) disease locus. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1552–59. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takeyama K, Kitanaka S, Sato T, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1alpha-hydroxylase and vitamin D synthesis. Science. 1997;277:1827–30. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson CC, Sisk JM, Beaudoin GM., 3rd Hairless and Wnt signaling: allies in epithelial stem cell differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1913–17. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Maldergem L, Bachy A, Feldman D, et al. Syndrome of lipoatrophic diabetes, vitamin D resistant rickets, and persistent müllerian ducts in a Turkish boy born to consanguineous parents. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:506–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960823)64:3<506::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang J, Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Interactions of the vitamin D receptor with the corepressor hairless: analysis of hairless mutants in atrichia with papular lesions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25231–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weisman Y, Bab I, Gazit D, et al. Long-term intracaval calcium infusion therapy in end-organ resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Am J Med. 1987;83:984–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitfield GK, Selznick SH, Haussler CA, et al. Vitamin D receptors from patients with resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: point mutations confer reduced transactivation in response to ligand and impaired interaction with the retinoid X receptor heterodimeric partner. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1617–31. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie Z, Chang S, Oda Y, et al. Hairless suppresses vitamin D receptor transactivation in human keratinocytes. Endocrinology. 2006;147:314–23. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshizawa T, Handa Y, Uematsu Y, et al. Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nat Genet. 1997;16:391–96. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou Y, Wang J, Malloy PJ, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in the vitamin D receptor in a patient with hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets with alopecia. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:643–51. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]