Abstract

Clinical and preclinical data concur that sleep disruption causes hyperalgesia, but the brain mechanisms through which sleep and pain interact remain poorly understood. Evidence that pontine components of the ascending reticular activating system modulate sleep and nociception encouraged the present study testing the hypothesis that hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) and an adenosine receptor agonist administered into the pontine reticular nucleus, oral part (PnO) each alter thermal nociception. Adult male rats (n = 23) were implanted with microinjection guide tubes aimed for the PnO. The PnO was microinjected with saline (control), hypocretin-1, the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-p-sulfophenyladenosine (SPA), the hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist N-(2-Methyl-6-benzoxazolyl)-N″-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl-urea (SB-334867), and hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867. As an index of antinociceptive behavior, the latency (in s) to paw withdrawal away from a thermal stimulus was measured following each microinjection. Compared to control, antinociception was significantly increased by hypocretin-1 and by SPA. SB-334867 increased nociceptive responsiveness, and administration of hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867 blocked the antinociception caused by hypocretin-1. These results suggest for the first time that hypocretin receptors in rat PnO modulate nociception.

Keywords: orexin, pain, sleep

In 2009, the American Pain Society35 and the National Sleep Foundation22 independently sponsored symposia on the topic of sleep and pain. The emerging appreciation of this relationship has been stimulated by evidence that pain states and sleep states are regulated by some of the same brain regions and neurotransmitters. Furthermore, preclinical1 and human14, 33, 36 studies make clear that sleep disruption causes hyperalgesia. These data are clinically relevant because opioids are a mainstay of pain management and opioids significantly disrupt sleep.24 Opioid-induced sleep disruption and ensuing hyperalgesia may in turn increase opioid requirement. Adjunctive therapies that aid in pain management while reducing sleep disruption would be of clinical value. A rational approach to development of pharmacotherapy that diminishes pain without disrupting sleep requires understanding the brain regions and molecules mediating the interaction between arousal states and pain.

The pontine reticular formation is part of an ascending projection system that regulates sleep/wake states23 and causes autonomic and behavioral activation in response to nociceptive input.32 The pontine reticular nucleus, oral part (PnO) is a component of the pontine reticular formation, and PnO administration of adenosine agonists alters sleep,8 time for emergence from anesthesia,38 and nociception.37, 41 The hypothalamic peptide hypocretin/orexin also modulates sleep/wake states (reviewed in29), emergence from volatile anesthesia,18 and nociception.2, 7, 27

No previous studies have determined whether adenosinergic and hypocretinergic neurotransmission in rat PnO alter nociception. The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that adenosinergic and hypocretinergic agonists microinjected into rat PnO enhance thermal antinociception. Portions of these data have been presented as abstracts.43-45

Methods

Animal Care and Surgical Preparation

All experiments and procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals and conformed to the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication 80-23, National Academy of Sciences Press, Washington DC, 1996). Adult male Crl:CD*(SD) (Sprague-Dawley) rats (n = 23) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) and allowed to acclimate for a minimum of one week prior to beginning experiments. Rats were housed in ventilated cages in the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine facilities on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00) with ad libitum access to food and water.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction = 3.5%; maintenance = 1.5-2.0%) and unilaterally implanted with an 8IC315GSPCXC model guide cannula (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) that was aimed to terminate above the stereotaxic coordinates of 8.4 mm posterior to bregma, 1.0 mm lateral to bregma, and 9.2 mm ventral to the skull surface.30 When inserted into the guide cannula, the tip of the microinjector extended below the guide cannula into the PnO. At the end of each surgery, the guide tube was closed with a Plastics One obturator (model 8IC315DCSPCC) and anesthesia delivery was terminated. Animals were then removed from the stereotaxic frame and returned to their home cages where they were observed until they were ambulatory.

Rats recovered from surgery for at least one week before nociceptive testing. During the recovery period, rats were placed in the chambers of a Model 336T Paw Stimulator Analgesia Meter (IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA) and given 1 h to habituate to the chambers. Characteristics of habituation included behavioral evidence of normal grooming and sleeping during the 1-h conditioning periods. Conditioning occurred daily for a minimum of one week. After the conditioning periods, the obturator was removed and a microinjector (model 8IC315IXXXXC, Plastics One) was inserted and removed. The obturator then was replaced. These steps simulated a microinjection and were used to further condition the rats to the handling required for subsequent experiments.

Microinjections and Nociceptive Testing

On data collection days, rats were habituated to the recording chambers for 1 h. The paw withdrawal latency (PWL) baselines were determined by 5 single measurements each separated by 5 min. These 5 single measurements were averaged to represent the overall baseline latency. The Hargreaves' PWL method15 was used to measure drug effects on the thermal nociceptive responses. Using the analgesia meter, the thermal source (a light beam with adjustable intensity) was focused on the plantar surface of a hind paw. Once the beam was appropriately aligned, the light was switched from idle intensity (10%) to active intensity (40%) simultaneously with onset of a timer. When the rat moved its paw away from the thermal stimulus, the timer was deactivated and the light returned to idle intensity. PWL was recorded as the time (in s) required for the rat to move its paw away from the thermal stimulus. Measurements were alternated between left and right paws to prevent any one paw from becoming sensitized to the thermal stimulus. After baseline measurements, the obturator was removed from the guide cannula and a microinjector was inserted.

The PnO was microinjected with 100 nL of either 0.9% saline (vehicle control) or drug. Two series of microinjection experiments were performed. Rats in Series 1 (n=12) received hypocretin-1 (35.6 ng; 10 pmol; California Peptide Research, Inc., Napa, CA, USA) and the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-p-sulfophenyladenosine (SPA; 227 ng; 500 pmol; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). In the second series of experiments, rats (n=11) were microinjected with hypocretin-1 (35.6 ng; 10 pmol), the hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist N-(2-Methyl-6-benzoxazolyl)-N″-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl-urea (SB-334867; 0.34 ng; 1 pmol; Tocris Bioscience Ellisville, MO, USA), and hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867 (35.6 ng and 0.34 ng, respectively; 10 pmol and 1 pmol, respectively). Each rat in Series 1 and Series 2 received all drug injections. Microinjections in the same rat were separated by at least one week.

Microinjections (60 s duration) were made using a manually driven microdrive equipped with a 1 μL syringe (Model 700, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). The microinjector was then removed and the obturator was replaced. After the microinjection, three PWL measurements were taken in rapid succession (within 1 to 1.5 min) at each of the following time points (in min): 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120. As with baseline conditions, the measurements alternated between the left and right hind paws. For example, at the 10 min mark, a measurement was taken on the left paw. Immediately after this measurement, the beam was focused onto the right hind paw for the second measurement. Immediately after the second measurement, the beam was once again focused on the left paw, but was aimed at a different spot on the paw from the first measurement to avoid possible desensitization or sensitization. No differences in PWL were observed between the paws that were ipsilateral and contralateral to the microinjection. After the last measurement, the rats were returned to their home cages.

Histological Confirmation of Microinjection Sites

Upon completion of the last PWL test, rats were deeply anesthetized and decapitated. Serial, coronal brain stem sections (40 μm thick) were stained with cresyl violet. All sections containing a microinjection site were digitized and compared with a rat brain atlas30 to determine the three-dimensional coordinates in relation to bregma. Only experiments with the microinjection site in the PnO were included in the data analysis.

Statistical Analyses of Paw Withdrawal Latency Data

PWL measurements were converted into percent maximum possible effect (%MPE)16 where %MPE = (post microinjection PWL – Baseline PWL)/(20 s – post microinjection PWL) × 100. For Series 1, the baseline values collected following microinjection of saline, hypocretin-1, and SPA were averaged for each rat to give 1 baseline value per rat. The same method was used for Series 2. The baseline value for a Series 2 rat was the average of the baseline values obtained prior to microinjection of saline, hypocretin-1, hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867, and SB-334867. The 20 s in the equation represents the cutoff time, defined as the time at which the thermal source automatically shuts off to avoid tissue damage. The %MPE calculation accounts for individual differences in the baseline responses to the nociceptive stimulation and the thermal stimulus cutoff time.

Statistical analyses were performed using GBStat™ (v.6.5.6, Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA) and GraphPad Prism™ (v.5.0a, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Time course %MPE data were evaluated by repeated measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The %MPE data averaged over the 120 min duration of the experiment were evaluated with one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Dunnett's multiple comparisons procedure. A probability (p) value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Microinjection Sites were Localized to the PnO

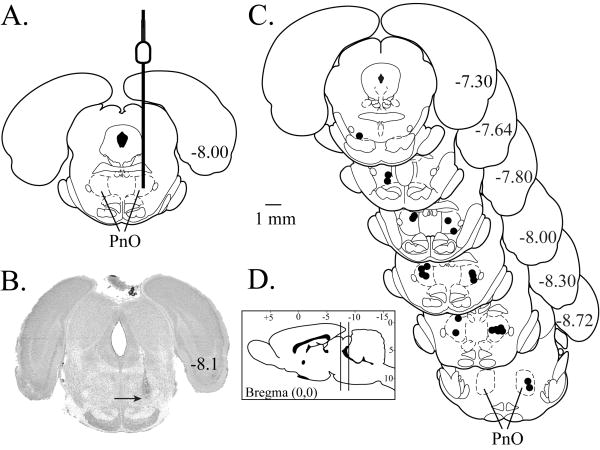

Histological analyses show that all microinjection sites (Fig. 1A) were confirmed to be in the PnO. In Fig. 1B, a digitized section illustrates one PnO microinjection site (arrow). Fig. 1C schematizes the location of each microinjection site on coronal diagrams modified from a rat brain atlas.30 The average ± SEM stereotaxic coordinates of all microinjection sites were 8.0 ± 0.1 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 ± 0.1 mm lateral to midline, and 8.3 ± 0.1 mm ventral to the skull surface.30 ANOVA revealed no differences in %MPE due to the posterior, lateral, or ventral stereotaxic coordinates of the microinjection sites.

Figure 1.

Histological localization of microinjection sites. A. The coronal diagram modified from a rat brain atlas30 schematizes the placement of a microinjector into the PnO. The diameter of the microinjector has been drawn to scale. B. The cresyl violet-stained coronal section illustrates a representative microinjection site (arrow) in the PnO. C. Schematic coronal diagrams were modified from a rat brain atlas.30 These diagrams span from 7.30 mm to 8.72 mm posterior to bregma and show the location of each microinjection site (black circles). D. The anterior to posterior range of all microinjection sites used in this study is indicated by the vertical lines in the sagittal diagram modified from a rat brain atlas.30 The 1 mm calibration bar applies to parts A-C.

Hypocretin-1 and SPA Increased Paw Withdrawal Latency

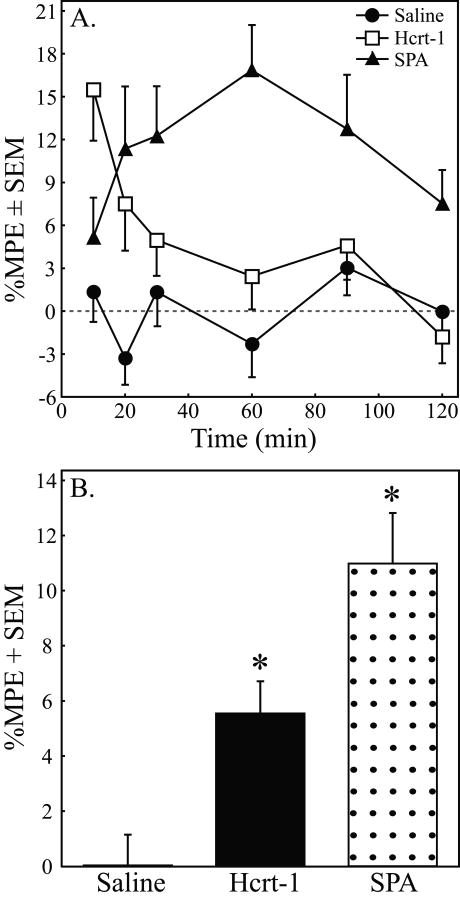

Table 1 reports the time course of paw withdrawal latencies for each rat used in Series 1 following microinjection of saline (A), hypocretin-1 (B), and SPA (C). Table 1 shows that the %MPE effect size (5 to 20%) was consistent with that of other studies. Table 1 also shows the variability in PWL, revealing that the coefficients of variation (%CV) across drug treatment conditions and across time points were comparable. Figure 2A plots the time course for mean %MPE measures of paw withdrawal following microinjection of saline, SPA, and hypocretin-1. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures indicated a significant increase in %MPE caused by hypocretin-1 (F = 11.64; df = 5, 350; p = 0.0011) and SPA (F = 25.95; df = 5, 350; p < 0.0001). A significant main-effect of time post-injection (F = 3.85; df = 5, 350; p = 0.0021) and drug by time interaction (F = 3.09; df = 5, 350; p = 0.0096) were also observed after microinjection of hypocretin-1. Figure 2B depicts the %MPE averaged over the 2 h post-injection period following microinjection of saline, SPA, and hypocretin-1. Compared to control, hypocretin-1 and SPA significantly increased antinociception by 5.51% and 10.95%, respectively. ANOVA revealed a significant drug main-effect on %MPE (F =14.97; df = 2, 70; p < 0.0001). Dunnett's procedure comparing the average %MPE after microinjection of saline to the average %MPE after injection of hypocretin-1 and SPA revealed that both hypocretin-1 and SPA significantly increased %MPE over the 2-h post-injection period (Fig. 2B, asterisks).

Table 1. Series 1 Raw Paw Withdrawal Latencies.

Raw latencies (in s) of paw withdrawal after PnO administration of saline (A), hypocretin-1 (B), and SPA (C). Data are reported at each post-injection time point. The far right column provides the average latency (in s) for each rat. The bottom four rows report the overall average, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), and coefficient of variation (%CV) for each time point. The bottom four values in the far right column of each table give the grand mean, standard deviation, standard error, and coefficient of variation of the mean for each treatment.

| A. Saline | Time Post-Injection (min) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean |

| R1 | 10,89 | 7.69 | 7.33 | 6.61 | 6.14 | 9.36 | 11.72 | 8.14 |

| R2 | 6.97 | 8.26 | 7.69 | 7.07 | 6.31 | 9.39 | 6.88 | 7.60 |

| R3 | 7.27 | 5.39 | 6.41 | 7.13 | 5.63 | 7.84 | 6.56 | 6.49 |

| R4 | 6.05 | 7.04 | 5.03 | 5.96 | 6.16 | 5.50 | 5.44 | 5.86 |

| R5 | 6.09 | 6.01 | 5.01 | 6.04 | 5.93 | 6.54 | 6.06 | 5.93 |

| R6 | 6.88 | 6.08 | 7.33 | 8.29 | 6.11 | 7.92 | 6.53 | 7.04 |

| R7 | 8.45 | 6.63 | 5.08 | 7.53 | 9.52 | 5.73 | 6.96 | 6.91 |

| R8 | 5.55 | 6.59 | 5.96 | 5.71 | 5.86 | 6.84 | 5.58 | 6.09 |

| R9 | 5.68 | 5.12 | 5.16 | 6.16 | 5.39 | 5.78 | 6.53 | 5.69 |

| R10 | 5.98 | 6.56 | 6.28 | 5.74 | 6.42 | 6.26 | 5.23 | 6.08 |

| R11 | 4.09 | 6.04 | 3.50 | 3.78 | 4.05 | 5.51 | 4.33 | 4.54 |

| R12 | 6.07 | 9.12 | 7.91 | 10.15 | 6.68 | 5.94 | 5.19 | 7.50 |

| Mean | 6.66 | 6.71 | 6.06 | 6.68 | 6.18 | 6.88 | 6.42 | 6.49 |

| SD | 1.63 | 1.12 | 1.29 | 1.50 | 1.20 | 1.36 | 1.77 | 0.96 |

| SEM | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.28 |

| %CV | 7.07 | 4.80 | 6.15 | 6.50 | 5.58 | 5.70 | 7.98 | 4.25 |

| B. Hypocretin-1 | ||||||||

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean |

| R1 | 8.15 | 12.40 | 8.41 | 8.59 | 9.57 | 7.94 | 6.04 | 8.83 |

| R2 | 6.20 | 9.39 | 6.19 | 6.48 | 8.24 | 7.29 | 6.66 | 7.38 |

| R3 | 5.92 | 6.48 | 10.39 | 7.79 | 8.22 | 6.57 | 5.63 | 7.52 |

| R4 | 6.07 | 7.52 | 5.98 | 5.70 | 7.28 | 6.71 | 5.93 | 6.52 |

| R5 | 6.22 | 5.46 | 5.00 | 6.25 | 5.91 | 5.90 | 6.29 | 5.80 |

| R6 | 8.71 | 11.54 | 7.64 | 9.99 | 7.23 | 8.82 | 7.87 | 8.85 |

| R7 | 6.84 | 9.04 | 7.81 | 7.56 | 7.54 | 9.49 | 5.88 | 7.89 |

| R8 | 4.85 | 10.16 | 6.89 | 9.69 | 5.11 | 6.71 | 5.45 | 7.34 |

| R9 | 5.25 | 8.16 | 8.44 | 5.73 | 6.76 | 7.33 | 6.03 | 7.07 |

| R10 | 6.97 | 7.24 | 12.76 | 6.26 | 6.71 | 6.54 | 7.30 | 7.80 |

| R11 | 5.33 | 9.53 | 4.46 | 5.49 | 4.58 | 5.63 | 5.63 | 5.89 |

| R12 | 5.66 | 5.53 | 5.98 | 6.27 | 4.10 | 6.15 | 6.71 | 5.79 |

| Mean | 6.35 | 8.54 | 7.50 | 7.15 | 6.77 | 7.09 | 6.28 | 7.22 |

| SD | 1.16 | 2.22 | 2.34 | 1.56 | 1.61 | 1.16 | 0.73 | 1.07 |

| SEM | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.31 |

| %CV | 5.26 | 7.50 | 9.00 | 6.31 | 6.88 | 4.74 | 3.35 | 4.26 |

| C. SPA | ||||||||

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean |

| R1 | 6.65 | 6.28 | 14.51 | 13.89 | 11.39 | 9.91 | 7.67 | 10.61 |

| R2 | 6.38 | 7.51 | 7.91 | 6.58 | 9.29 | 6.49 | 5.11 | 7.15 |

| R3 | 7.29 | 9.19 | 9.69 | 9.1 1 | 6.91 | 6.73 | 8.26 | 8.31 |

| R4 | 5.69 | 6.81 | 11.06 | 11.17 | 8.01 | 7.34 | 8.31 | 8.78 |

| R5 | 6.16 | 6.16 | 5.64 | 5.74 | 7.49 | 6.58 | 7.63 | 6.54 |

| R6 | 7.16 | 5.53 | 6.83 | 8.63 | 8.84 | 5.14 | 10.59 | 7.59 |

| R7 | 8.15 | 8.55 | 5.44 | 9.94 | 8.44 | 13.08 | 9.89 | 9.22 |

| R8 | 5.11 | 7.31 | 6.91 | 8.04 | 7.78 | 6.53 | 7.41 | 7.33 |

| R9 | 5.87 | 6.03 | 3.70 | 4.96 | 12.42 | 8.51 | 5.26 | 6.81 |

| R10 | 6.01 | 9.36 | 10.42 | 7.66 | 11.86 | 12.32 | 6.53 | 9.69 |

| R11 | 6.37 | 6.35 | 6.67 | 4.63 | 5.49 | 7.36 | 4.75 | 5.87 |

| R12 | 5.44 | 7.72 | 6.76 | 6.05 | 7.11 | 8.32 | 8.34 | 7.38 |

| Mean | 6.36 | 7.23 | 7.96 | 8.03 | 8.75 | 8.19 | 7.48 | 7.94 |

| SD | 0.86 | 1.27 | 2.97 | 2.73 | 2.14 | 2.43 | 1.82 | 1.40 |

| SEM | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.40 |

| %CV | 3.89 | 5.07 | 10.76 | 9.80 | 7.05 | 8.58 | 7.03 | 5.09 |

Figure 2.

Microinjection of hypocretin-1 and SPA into the PnO increased antinociceptive behavior. A. Percent maximum possible effect (%MPE) on paw withdrawal latency as a function of time and drug. Graphs summarize measures obtained during the two hours following microinjection of saline (n = 12 rats), hypocretin-1 (Hcrt-1, n = 12), and the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA (n = 12) into the pontine reticular formation. B. The %MPE averaged over 2 h after PnO microinjection of hypocretin-1 and SPA was significantly (*, p < 0.01) increased compared to saline.

SB-334867 Blocked the Hypocretin-1 Induced Increase in Antinociception

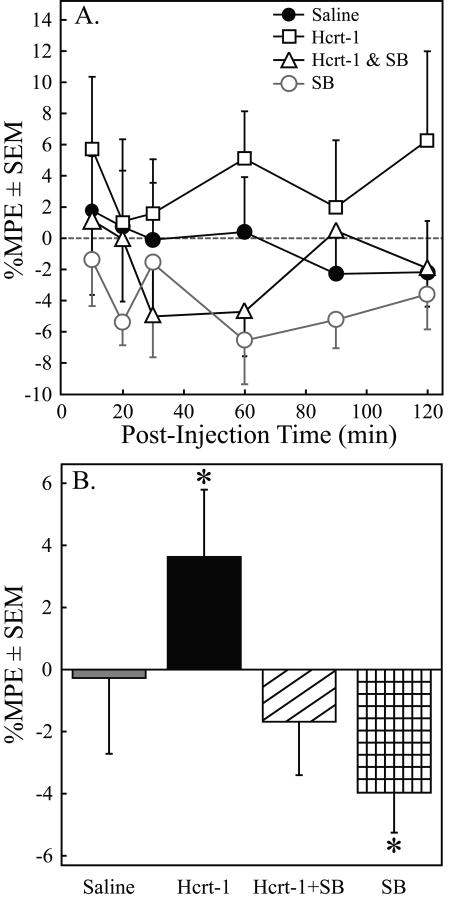

Table 2 shows the time course of paw withdrawal latencies after microinjection of saline (A), hypocretin-1 (B), hypocretin-1 + SB-334867 (C), and SB-334867 (D) for each rat in Series 2. The Table 2 data provide measures of variability (SD, SEM, %CV) at each time point for all four treatments. The mean %MPE for saline, hypocretin-1 (Hcrt-1), hypocretin-1 + SB-334867 (Hcrt-1+SB), and SB-334867 (SB) at each post-injection time point is presented in Figure 3A. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug main-effect for hypocretin-1 (F = 4.33; df = 1, 320; p = 0.04) and for SB-334867 (F = 4.78; df = 1, 320; p = 0.03). The comparison between the %MPE averaged over the 120 min post-injection period for saline, hypocretin-1, co-administration of hypocretin-1 and SB-334867, and SB-334867 is depicted in Figure 3B. ANOVA indicated a significant drug effect on %MPE (F = 7.44; df = 3, 113; p = 0.0001). Dunnett's test revealed that hypocretin-1 significantly (*p < 0.05) increased %MPE relative to saline and that this increased %MPE was blocked following co-administration of hypocretin-1 and SB-334867. Microinjection of SB-334867 increased nociceptive response as compared to saline.

Table 2. Series 2 Raw Paw Withdrawl Latencies.

Paw withdrawal latencies (in s) to a thermal nociceptive stimulus after PnO microinjection of saline (A), hypocretin-1 (B), hypocretin-1 + SB-334867 (C), and SB-334867 (D). Data from each rat are reported for each post-injection time point. The overall latency for each animal is in the far right column; the overall mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), and coefficient of variation (%CV) for each time point are located at the bottom of the table, and the grand means for the experimental condition are located in the bottom four rows of the far right column.

| A. Saline | Time Post-Injection (min) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean | |

| R1 | 7.55 | 7.91 | 12.54 | 9.46 | 8.51 | 7.88 | 9.24 | 9.25 | |

| R2 | 7.46 | 6.51 | 3.88 | 5.16 | 6.44 | 6.71 | 6.31 | 5.83 | |

| R3 | 6.27 | 8.89 | 4.76 | 5.46 | 5.09 | 5.46 | 6.42 | 6.01 | |

| R4 | 5.01 | 5.53 | 6.36 | 5.34 | 4.69 | 4.92 | 5.19 | 5.34 | |

| R5 | 6.17 | 5.11 | 6.08 | 6.21 | 5.55 | 5.96 | 5.06 | 5.66 | |

| R6 | 8.95 | 8.51 | 7.42 | 9.57 | 9.82 | 5.73 | 8.21 | 8.21 | |

| R7 | 5.81 | 5.09 | 5.88 | 5.01 | 5.96 | 5.15 | 5.53 | 5.44 | |

| R8 | 7.29 | 7.89 | 6.61 | 6.19 | 5.86 | 6.30 | 5.83 | 6.45 | |

| R9 | 6.40 | 6.77 | 6.24 | 6.16 | 6.46 | 6.46 | 5.24 | 6.22 | |

| R10 | 6.10 | 6.13 | 6.29 | 6.31 | 6.70 | 7.12 | 5.20 | 6.29 | |

| R11 | 5.73 | 4.71 | 5.21 | 5.25 | 5.71 | 5.28 | 4.77 | 5.15 | |

| Mean | 6.61 | 6.64 | 6.48 | 6.37 | 6.44 | 6.09 | 6.09 | 6.35 | |

| SD | 1.10 | 1.47 | 2.23 | 1.62 | 1.50 | 0.91 | 1.42 | 1.27 | |

| SEM | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.38 | |

| %CV | 5.02 | 6.69 | 10.37 | 7.68 | 7.03 | 4.51 | 7.01 | 6.02 | |

| B. Hypocretin-1 | |||||||||

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean | |

| R1 | 7.54 | 8.31 | 8.71 | 7.22 | 9.19 | 6.96 | 8.84 | 8.21 | |

| R2 | 6.42 | 7.59 | 6.39 | 4.80 | 6.93 | 6,76 | 5.67 | 6.36 | |

| R3 | 5.36 | 6.06 | 4.65 | 6.17 | 6.31 | 5.78 | 6.81 | 5.96 | |

| R4 | 5.47 | 4.30 | 5.34 | 3.98 | 4.59 | 5.42 | 4.73 | 4.73 | |

| R5 | 6.41 | 6.89 | 5.85 | 7.39 | 8.59 | 7.33 | 13.00 | 8.18 | |

| R6 | 5.89 | 9.67 | 7.64 | 7.71 | 7.74 | 5.23 | 10.66 | 8.11 | |

| R7 | 7.00 | 8.51 | 7.29 | 7.28 | 7.76 | 5.46 | 4.49 | 6.80 | |

| R8 | 6.87 | 8.66 | 7.08 | 7.49 | 6.73 | 10.67 | 6.97 | 7.93 | |

| R9 | 6.55 | 7.63 | 6.71 | 6.61 | 8.06 | 7.59 | 6.48 | 7.18 | |

| R10 | 5.52 | 5.47 | 6.90 | 8.57 | 6.35 | 6.07 | 6.40 | 6.63 | |

| R11 | 6.05 | 5.48 | 5.26 | 5.55 | 5.58 | 6.00 | 5.68 | 5.59 | |

| Mean | 6.28 | 7.14 | 6.53 | 6.62 | 7.08 | 6.66 | 7.25 | 6.88 | |

| SD | 0.70 | 1.65 | 1.19 | 1.37 | 1.35 | 1.55 | 2.60 | 1.17 | |

| SEM | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.35 | |

| %CV | 3.35 | 6.97 | 5.48 | 6.24 | 5.76 | 7.02 | 10.82 | 5.11 | |

| C. Hypocretin-1 + SB 334867 | |||||||||

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean | |

| R1 | 7.08 | 10.09 | 9.23 | 7.27 | 7.33 | 7.51 | 7.96 | 8.23 | |

| R2 | 7.00 | 8.01 | 6.94 | 6.57 | 6.19 | 7,29 | 7.38 | 7.06 | |

| R4 | 5.16 | 4.41 | 4.41 | 4.48 | 3.76 | 4.86 | 5.17 | 4.52 | |

| R7 | 6.64 | 5.58 | 5.01 | 4.56 | 5.88 | 5.51 | 6.77 | 5.55 | |

| R8 | 7.21 | 5.55 | 6.24 | 5.91 | 7.60 | 7.89 | 5.50 | 6.45 | |

| R9 | 6.31 | 6.84 | 6.67 | 5.83 | 5.22 | 6.08 | 5.92 | 6.09 | |

| R10 | 6.33 | 6.62 | 6.22 | 5.95 | 5.09 | 6.43 | 5.94 | 6.04 | |

| R11 | 5.82 | 5.58 | 6.75 | 5.65 | 5.32 | 6.53 | 4.93 | 5.79 | |

| Mean | 6.44 | 6.58 | 6.43 | 5.78 | 5.80 | 6.51 | 6.20 | 6.22 | |

| SD | 0.70 | 1.78 | 1.43 | 0.93 | 1.25 | 1.03 | 1.08 | 1.10 | |

| SEM | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.33 | |

| %CV | 3.28 | 8.16 | 6.72 | 4.88 | 6.50 | 4.77 | 5.24 | 5.31 | |

| D. SB-334867 | |||||||||

| Rat ID | BL | 10 | 20 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | Mean | |

| R2 | 7.43 | 7.24 | 6.24 | 6.67 | 5.36 | 6.43 | 6.72 | 6.45 | |

| R3 | 5.52 | 5.61 | 4.94 | 4.69 | 5.38 | 4.55 | 5.79 | 5.16 | |

| R4 | 4.05 | 4.43 | 3.58 | 4.85 | 5.10 | 4.71 | 4.61 | 4.55 | |

| R5 | 5.87 | 6.36 | 5.56 | 7.89 | 5.25 | 4.86 | 5.26 | 5.86 | |

| R6 | 5.65 | 4.64 | 6.11 | 5.69 | 4.75 | 5.26 | 5.73 | 5.36 | |

| R7 | 6.46 | 6.68 | 5.65 | 5.20 | 4.90 | 5.97 | 5.46 | 5.64 | |

| R9 | 6.70 | 6.62 | 6.39 | 6.91 | 5.31 | 6.16 | 6.11 | 6.25 | |

| R10 | 6.71 | 5.62 | 5.36 | 5.81 | 6.34 | 6.12 | 5.93 | 5.86 | |

| R11 | 6.37 | 6.94 | 5.24 | 6.18 | 5.56 | 5.34 | 5.81 | 5.84 | |

| Mean | 6.08 | 6.02 | 5.45 | 5.99 | 5.33 | 5.49 | 5.71 | 5.66 | |

| SD | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.04 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.58 | |

| SEM | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 | |

| %CV | 5.31 | 5.54 | 5.21 | 5.80 | 2.85 | 4.26 | 3.40 | 3.39 | |

Figure 3.

The hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist SB-334867 blocked the hypocretin-1-induced increase in antinociception. A. The time course for the mean percent maximum possible effect (%MPE) measures of PWL following microinjection of saline (n = 11 rats), hypocretin-1 (Hcrt-1, n = 11), the hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist SB-334867 (SB, n = 9), and hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867 (Hcrt-1+SB, n = 8). B. Percent maximum possible effect (%MPE) on paw withdrawal latency averaged over 2-h after PnO microinjection of saline, hypocretin-1, hypocretin-1 plus SB-334867, and SB-334867 alone. PnO microinjection of hypocretin-1 increased average %MPE as compared to saline. The increase in antinociception due to PnO microinjection of hypocretin-1 was blocked when hypocretin-1 was co-administered with the hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist SB-334867. SB-334867 increased nociceptive responses when administered alone. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in %MPE (p < 0.01) compared to saline.

Discussion

The results show that the peptide hypocretin-1 and the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA increase thermal antinociception when microinjected into the PnO. The hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist SB-334867 blocked the increase in thermal antinociception caused by hypocretin-1. These data suggest for the first time that within the PnO (Fig. 1), hypocretin receptor-1 may play a role in thermal antinociception. The findings are discussed in relation to adenosinergic and hypocretinergic modulation of pain and arousal states.

Adenosine is a neuromodulator formed during energy metabolism10 and PnO administration of adenosine agonists in rat25 and mouse8 increases sleep. Adenosine can also be antinociceptive11 and in the present study thermal antinociception was increased by PnO microinjection of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These results are consistent with evidence that PnO microinjection of the adenosine A1 receptor agonist SPA into the pontine reticular formation of cat37 and mouse41 causes antinociception. The good agreement between data obtained from three species provides compelling support for the interpretation that adenosine receptors in brain regions known to regulate sleep/wake states, such as the pontine reticular formation, can also influence pain states.

Hypocretin-1 is a peptide synthesized by neurons in the lateral hypothalamus.34 Hypocretin-containing neurons project to multiple arousal-related brain regions, including the pontine reticular formation.31 Hypocretin-1 promotes wakefulness (reviewed in29) and microinjection of hypocretin-1 into rat PnO increases wakefulness.42 The present results showing that PnO microinjection of hypocretin-1 is antinociceptive are consistent with a growing body of evidence that hypocretin-1 can alter pain transmission. For instance, microinjection of hypocretin-1 into rat posterior hypothalamus2 decreases responses to nociceptive input.

Hypocretin-1 has also been shown to cause antinociception during thermal,5, 27 mechanical,27 and chemical5, 27 nociceptive stimuli in mouse and rat when administered intracerebroventricularly or intrathecally.27 In comparison to these reports, the present study found modest increases in antinociception. However, studies involving intrathecal or intracerebroventricular injections used doses of hypocretin-1 ranging from 30 pmol to 240 nmol.5, 27 One study showed that 30 pmol of hypocretin-1 caused a maximum %MPE of approximately 5%,5 which is similar to the current results obtained by microinjecting 10 pmol. The present finding of statistically significant antinociception due to a small percent change emphasizes the robustness of the drug effect. Hypocretin-1 is an endogenous neuropeptide and the statistically significant but modest increase in antinociception induced by PnO microinjection of hypocretin-1 may reflect tightly regulated hypocretinergic signaling within the brain. Synthetic agonists for hypocretin receptors may cause more efficacious antinociception.

Intrathecal7, 46, 47 and intracerebroventricular46 administration of hypocretin-1 suppresses mechanical allodynia in rat models of postoperative,7 neuropathic,46 and inflammatory47 pain. Morphine also suppresses mechanical allodynia when administered systemically4, 12 or intracerebroventricularly4 in rat models of neuropathic pain. When morphine is given intrathecally, however, mechanical allodynia is not suppressed.4 The differences in suppression of mechanical allodynia due to intrathecal administration of hypocretin-1 or morphine may be due to the presence of hypocretin-19, 40 and its receptors17 in the spinal cord, as well as a possible reduction of spinal μ-opioid receptors resulting from neuropathic pain models.4 Even though hypocretin-1 and morphine have similar effects on mechanical allodynia when given intracerebroventricularly, these compounds have very different effects on arousal.

The reticular formation comprises a brainstem network that promotes the arousal and autonomic responses to nociceptive input.32 Although the reticular formation is not considered part of ascending pain pathways, it has been known for more than 10 years that areas of the reticular formation that regulate sleep can also alter nociception.20 Cholinomimetics administered to the PnO cause antinociception,20, 41 and microdialysis delivery of hypocretin-1 to rat PnO increases acetylcholine release in the PnO.3 The present results (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 3) provide the first evidence that hypocretin-1 administered to the PnO is antinociceptive.

Limitations and Conclusions

This study was limited to evaluating acute thermal nociception and the results may not generalize to other sensory modalities of other types of pain. The results encourage future efforts to address this limitation and evaluate the antinocieptive effects of PnO hypocretin-1 using chemical, surgical,6 and genetic13 models of chronic pain. A second limitation of this study is the use of only male rats. Sex differences have been observed in response to thermal nociception.28 Future studies should investigate whether sex differences occur in hypocretin-1-induced antinociception. The present study also did not examine possible circadian variations in the antinociceptive effects of hypocretin-1. Some hypocretin neurons in the medial and dorsal tuberal hypothalamus coexpress higher levels of c-Fos during the dark period, indicating cell activation.26 These data suggest that hypocretinergic neurons display circadian activity rhythms. Hypocretin-1 levels in the basal forebrain (ranging from approximately 1.0 to 1.3 fmol/20 μL) and lateral hypothalamus (ranging from approximately 1.25 to 1.6 fmol/20 μL) are lowest during non-rapid eye movement sleep.19 Although some circadian influence may be present, the use of 10 pmol/0.1 μL in the present study, a concentration much higher than endogenous levels, most likely overcame any variations due to circadian rhythms.

Microinjection of saline into the PnO caused a non-significant decrease in %MPE (Fig. 3B). The reasons for this decrease are not known. Saline may have diluted endogenous molecules in the PnO that normally have antinociceptive effects.

Although the antinociception caused by SPA is consistent with data obtained from mouse,41 the present use of SPA limits inferences to adenosine A1 receptors. In previous studies, antinociception caused by PnO administration of SPA was blocked by an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist.37 The conclusion that the present antinociceptive effects were receptor mediated also is consistent with the fact that receptors for adenosine and hypocretin-1 are coupled to guanine nucleotide binding proteins which are activated in rat PnO by hypocretin3 and SPA.39

The good agreement that hypocretin-1 promotes behavioral arousal29 and evidence that hypocretin-1 is antinociceptive suggests that there is potential for hypocretin-1 to alleviate pain without depressing wakefulness. Future studies are needed in order to determine if performance or cognitive function can be improved by coadministering hypocretin-1 combined with opioids compared to administering opioids alone. Hypocretin-1 has been shown to facilitate emergence from anesthesia18 without any change in induction time.18, 21 The shortened emergence time has been attributed to actions at the hypocretin receptor-1.18, 21 Identification of an endogenous peptide that decreases both pain and anesthesia recovery time is of considerable interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants HL57120, HL40881, MH45361, and the Department of Anesthesiology. We thank A.S. Battersby, S. Jiang, and M.A. Norat for expert assistance.

Footnotes

Perspective: Widely distributed and overlapping neural networks regulate states of sleep and pain. Specifying the brain regions and neurotransmitters through which pain and sleep interact is an essential step for developing adjunctive therapies that diminish pain without disrupting states of sleep and wakefulness.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baghdoyan HA. Hyperalgesia induced by REM sleep loss: a phenomenon in search of a mechanism. Sleep. 2006;29:137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsch T, Levy MJ, Knight YE, Goadsby PJ. Differential modulation of nociceptive dural input to [hypocretin] orexin A and B receptor activation in the posterior hypothalamic area. Pain. 2004;109:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard R, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Hypocretin (orexin) receptor subtypes differentially enhance acetylcholine release and activate G protein subtypes in rat pontine reticular formation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:163–171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bian D, Nichols ML, Ossipov MH, Lai J, Porreca F. Characterization of the antiallodynic efficacy of morphine in a model of neuropathic pain in rats. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1981–1984. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199510010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingham S, Davey PT, Babbs AJ, Irving EA, Sammons MJ, Wyles M, Jeffrey P, Cutler L, Riba I, Johns A, Porter RA, Upton N, Hunter AJ, Parsons AA. Orexin-A, an hypothalamic peptide with analgesic properties. Pain. 2001;92:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brummett CM, Norat MA, Palmisano JM, Lydic R. Perineural administration of dexmedetomidine in combination with bupivacaine enhances sensory and motor blockade in sciatic nerve block without inducing neurotoxicity in rat. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:502–511. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182c26b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng JK, Chou RCC, Hwang LL, Chiou LC. Antiallodynic effects of intrathecal orexins in a rat model of postoperative pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:1065–1071. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.056663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman CG, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Dialysis delivery of an adenosine A2A agonist into the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse increases pontine acetylcholine release and sleep. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1750–1759. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Date Y, Mondal MS, Matsukura S, Nakazato M. Distribution of orexin-A and orexin-B (hypocretins) in the rat spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 2000;288:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenach JC, Hood DD, Curry R. Preliminary efficacy assessment of intrathecal injection of an American formulation of adenosine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:29–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erichsen HK, Hao JX, Xu XJ, Blackburn-Munro G. Comparative actions of the opioid analgesics morphine, methadone and codeine in rat models of peripheral and central neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;116:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geisser ME, Wang W, Smuck M, Koch LG, Britton SL, Lydic R. Nociception before and after exercise in rats bred for high and low aerobic capacity. Neurosci Lett. 2008;443:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haack M, Mullington JM. Sustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-being. Pain. 2005;119:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes RL, Katayama Y, Watkins LR, Becker DP. Bilateral lesions of the dorsolateral funiculus of the cat spinal cord: effects on basal nociceptive reflexes and nociceptive suppression produced by cholinergic activation of the pontine parabrachial region. Brain Res. 1984;311:267–280. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hervieu GJ, Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Roberts JC, Leslie RA. Gene expression and protein distribution of the orexin-1 receptor in the rats brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;103:777–797. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, Cheng Meng Q, Moore JT, Veasey SC, Dixon S, Thornton M, Funato H, Yanagisawa M. An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1309–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Maidment N, Lam HA, Wu MF, John J, Peever J, Siegel JM. Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5282–5286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kshatri AM, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Cholinomimetics, but not morphine, increase antinociceptive behavior from pontine reticular regions regulating rapid-eye-movement sleep. Sleep. 1998;21:677–685. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushikata T, Hirota K, Yoshida H, Kudo M, Lambert DG, Smart D, Jerman JC, Matsuki A. Orexinergic neurons and barbiturate anesthesia. Neuroscience. 2003;121:855–863. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavigne G, Roehrs T. Pain and sleep: A scientific and clinical conference. Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Sleep, anesthesiology, and the neurobiology of arousal state control. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1268–1295. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Neurochemical mechanisms mediating opioid-induced REM sleep disruption. In: Lavigne G, Sessle BJ, Choinière M, Soja PJ, editors. Sleep and Pain. IASP Press; Seattle: 2007. pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks GA, Birabil CG. Enhancement of rapid eye movement sleep in the rat by cholinergic and adenosinergic agonists infused into the pontine reticular formation. Neuroscience. 1998;86:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marston OJ, Williams RH, Canal MM, Samuels RE, Upton N, Piggins HD. Circadian and dark-pulse activation of orexin/hypocretin neurons. Molecular Brain. 2008;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mobarakeh JI, Takahashi K, Sakurada S, Nishino S, Watanabe H, Kato M, Naghdi N, Yanai K. Enhanced antinociception by intracerebroventricularly administered orexin A in histamine H1 or H2 receptor gene knockout mice. Pain. 2005;118:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mogil JS, Chesler EJ, Wilson SG, Juraska JM, Sternberg WF. Sex differences in thermal nociception and morphine antinociception in rodents depend on genotype. Neurosci Behav Rev. 2000;24:375–389. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishino S, Sakurai T. The Orexin/Hypocretin System: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th. Academic Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price DD. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science. 2000;288:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roehrs T, Hyde M, Blaisdell B, Greenwald M, Roth T. Sleep loss and REM sleep loss are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006;29:145–151. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith MT. The role of sleep in hyperalgesia and persistent pain. American Pain Society 28th Annual Scientific Meeting; San Diego, CA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MT, Edwards RR, McCann UD, Haythornthwaite JA. The effects of sleep deprivation on pain inhibition and spontaneous pain in women. Sleep. 2007;30:494–505. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanase D, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Microinjection of an adenosine A1 agonist into the medial pontine reticular formation increases tail flick latency to thermal stimulation. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1597–1601. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanase D, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Dialysis delivery of an adenosine A1 receptor agonist to the pontine reticular formation decreases acetylcholine release and increases anesthesia recovery time. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:912–920. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanase D, Martin WA, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. G protein activation in rat pontomesencephalic nuclei is enhancd by combined treatment with a mu opioid and an adenosine A1 receptor agonist. Sleep. 2001;24:1–11. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van den Pol AN. Hypothalamic hypocretin (orexin): robust innervation of the spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3171–3182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03171.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Leptin replacement restores supraspinal cholinergic antinociception in leptin deficient obese mice. J Pain. 2009;10:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson CJ, Soto-Calderon H, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Pontine reticular formation (PnO) administration of hypocretin-1 increases PnO GABA levels and wakefulness. Sleep. 2008;31:453–464. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson SL, Battersby AS, Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Washington, DC: Society of Neuroscience; 2008. [08/25/2009]. Increase in antinociception caused by microinjection of hypocretin-1 (hcrt-1) into the pontine reticular nucleus, oral part (PnO) of Sprague Dawley rat is blocked by the hcrt receptor-1 (hcrt-r1) antagonist SB-334867. Program No. 270.18. 2008 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Online. URL. http://www.abstractsonline.com/Plan/ViewSession.aspx?mID=1668&sKey=b5b4ad51-dff5-429c-a2fa-f9e4a7915223. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson SL, Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience; 2006. [08/25/2009]. Response to nociceptive input is decreased by the adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-p-sulfophenyladenosine (SPA), but not by hypocretin-1 (hcrt), microinjected into the pontine reticular formation (PRF) of Sprague-Dawley rat. Program No. 248.5. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Online. URL. http://www.abstractsonline.com/viewer/viewAbstractPrintFriendly.aspCKey={B1B2DAF1-8A62-4907-8914-8045B8391D79}&SKey={758FF20AA555-4CC8-9BB3-3949330452BA}&MKey={D1974E76-28AF-4C1C-8AE8-4F73B56247A7}&AKey={3A7DC0B9-D787-44AA-BD08-FA7BB2FE9004} [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson SL, Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Microinjection of hypocretin-1 into the pontine reticular nucleus, oral part (PnO) of Sprague-Dawley rat decreases response to nociceptive input. J Pain. 2008;9(Suppl 2):P7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto T, Saito O, Shono K, Aoe T, Chiba T. Anti-mechanical allodynic effect of intrathecal and intracerebroventricular injection of orexin-A in the rat neuropathic pain model. Neurosci Lett. 2003;347:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto T, Saito O, Shono K, Hirasawa S. Activation of spinal orexin-1 receptor produces anti-allodynic effect in the rat carrageenan test. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;481:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]