Abstract

Graves' disease, an autoimmune process associated with thyroid dysfunction, can also manifest as remodeling of orbital connective tissue. Affected tissues exhibit immune responses that appear to be orchestrated by resident cells and those recruited from the bone marrow through their expression and release of cytokines and surface display of cytokine receptors. Cytokines are small molecules produced by many types of cells, including those of the “professional” immune system. Aberrant cytokine expression appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including thyroid autoimmunity. The skewed pattern of cytokine expression in the thyroid, including the T helper cell bias, may condition the response to apoptotic signals and determine the characteristics of an autoimmune reaction. Furthermore, chemoattractant cytokines, including IL16, RANTES, and CXCL10, elaborated by resident cells in the thyroid and orbit may provoke mononuclear cell infiltration. Other cytokines may drive cell activation and tissue remodeling. Thus cytokines and the signaling pathways they activate represent attractive therapeutic targets. Interruption of these might alter the natural course of Graves' disease and its orbital manifestations.

Introduction

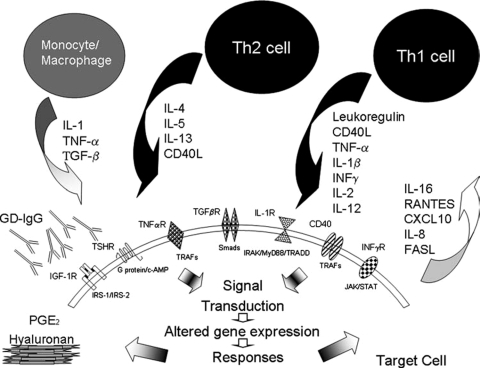

Graves' disease (GD) represents both the most common cause of hyperthyroidism and an archetypical example of antibody-mediated autoimmunity. It is associated with an inflammatory process in the orbit known as thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO). Abnormalities in the levels of several abundant cytokines have been documented in thyroid and orbital tissues in GD. Cytokines are small molecules synthesized by many different cell types and playing important roles in health and disease (1,2). Some are expressed as membrane-bound proteins while others are released as soluble molecules targeting high-affinity receptors on the surfaces of adjacent cells. They function as elaborate networks and therefore the aggregate contribution of many different molecular mediators represents the basis for the pattern of tissue reactivity found in disease (Fig. 1). The profile of cytokines appears to define the nature of organ-specific immune responses. Their central roles in inflammation suggest that they, their receptors, and the signaling pathways they utilize are potentially attractive therapeutic targets for autoimmune diseases of the thyroid.

FIG. 1.

Cytokine-mediated cellular interactions in autoimmune thyroid disease. Resident cells recruit those of the “professional” immune system by elaborating chemoattractant cytokines. These cells infiltrate target tissue and contribute to the cytokine milieu. The cytokine profile is dependent on the T cell subtype recruited. Cytokine actions are mediated predominantly through their ligating cognate receptors. Autoantibodies also target and activate cells through their occupancy of cell surface receptors, including TSHR and IGF-1R. PGE2 and hyaluronan production is provoked by pro-inflammatory cytokines.

GD and the Thyroid

Thyroid tissue becomes hyperplastic, hypertrophied, and infiltrated with B and T lymphocytes in GD. CD4+ cells predominate and these are accompanied by moderate B cell germinal center formation (3,4). GD is generally characterized by a Th2 pattern of cytokine production. Intrathyroidal lymphocytes secrete cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13, all of which tend to support antibody-mediated immune responses. This cytokine milieu may result from the contributions of both residential cells such as thyrocytes, endothelium, and fibroblasts and by cells recruited to the gland, including T cells. We postulate that epithelium and the other residential elements of the thyroid play important roles in defining the pattern of inflammation and tissue remodeling found in GD.

A key aspect of tissue remodeling concerns the process of apoptosis. Thyrocytes from individuals with GD express both Fas and FasL (5,6). The cytokine profile found in thyroid tissue in autoimmunity may contribute to the exaggerated susceptibility to apoptosis seen in Hashimoto's thyroiditis and in other destructive processes. Conversely, the relative resistance to apoptosis found in GD may be conditioned by a different pattern of cytokine expression. Th1-type cytokines predominating in Hashimoto's thyroiditis such as interferon (INF)-γ, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are associated with cell-mediated immunity. These promote Fas-mediated apoptosis through the induction of enzymes known as caspases. In contrast, through their expression of FasL, thyrocytes, intrathyroidal macrophages, and dendritic cells promote apoptosis in infiltrating lymphocytes displaying Fas (6,7). Th2-type cytokines protect thyrocytes in GD by up-regulating anti-apoptotic proteins, such as cFLIP and Bcl-xL (5,6,8). Thus, while the role of cytokines in apoptosis is complex and incompletely understood, cytokine profiles in GD and Hashimoto's thyroiditis might account for the clinical presentations that distinguish the two processes.

We suspect that thyrocytes participate in immune responses by virtue of their capacity to both produce cytokines and to respond to them. IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, IL-16, CXCL-10, CXCL-19, and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) are synthesized by thyrocytes in vitro (9–12). Of these, IL-16 and RANTES represent potent T lymphocyte chemoattractant molecules, and their production by thyrocytes may be an important basis for lymphocyte trafficking to the diseased thyroid (10,13,14). Thyrocytes, orbital fibroblasts, and adipocytes in culture secrete CXCL10 in response to INF-γ and TNF-α, effects attenuated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ agonists (15). CXCR3 the cognate receptor for CXCL10 is expressed at high levels on lymphocytes (16) and endothelial cells (17), suggesting another mechanism involving CXCL10 through which recruitment of lymphocytes to the thyroid and orbit in GD might occur. Serum CXCL10 levels are elevated in patients with TAO (15,18). They are particularly high in recent-onset GD and during the active phase of TAO (19).

Cross-talk between thyrocytes and infiltrating lymphocytes can occur through a number of signaling pathways. Prominent among these is CD40 and its cognate ligand CD154 (also known as CD40 ligand). CD40, a member of the TNF-α receptor superfamily, was originally discovered on B cells where it functions in lymphocyte activation. Elevated levels of CD40 are found in situ in GD on thyrocytes (20) and its engagement in cultured cells has been shown to induce IL-6 production (21). A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the CD40 gene has been associated with susceptibility to GD (22). This SNP enhances translational efficiency of CD40 mRNA and increases modestly (15–32%) B-cell surface display of the protein (23). The threshold of cell activation might decline as a result.

Cytokines can modulate thyroid epithelial cell growth and function (24,25). IL-1, TNF-α, and INF-α, -β, and -γ have been shown to inhibit thyrotropin (TSH) dependent [125I] uptake and thyroid hormone release by cultured human thyrocytes (26,27). These cytokine effects are synergistic and reversible. Gerard et al. (28) demonstrated that treatment of thyrocytes with the Th1 cytokine combination IL-1α/INF-γ resulted in reduced thyroid peroxidase (TPO) protein and mRNA expression. TPO is a critical thyroidal enzyme responsible for iodine organification, the first step in thyroid hormone synthesis. Effects of cytokines on other key thyroidal functions such as sodium-iodide symporter expression (29), thyroglobulin production, and cAMP generation (30) have also been reported. In addition, IL-1β induces production of hyaluronan by primary thyroid epithelial cells and thyroid fibroblasts, a process that may contribute to the development of goiter in GD (31). It is likely that the intrathyroidal milieu of molecular mediators, including cytokines and anti-thyroid antibodies modulate thyroid function and goiter formation. Furthermore, INF-γ enhances the expression of major histocompatibility complex (HLA) class I and class II on thyrocytes (25), potentially enhancing antigen presentation (24). Additionally, HLA-DR3, a class II molecule exhibits high affinity binding with TSH-receptor (TSH-R) peptides (32). Complexing of HLA-DR3 with TSH-R may modify TSH-R surface expression and TSH-R epitope presentation to the immune system.

Systemic cytokine administration can result in thyroid dysfunction. INF-α, used in the treatment of hepatitis, can result in hypothyroidism (33,34). However, it can also provoke hyperthyroidism and the generation of thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI) (35). Patients developing detectable TSI following INF-α therapy rarely manifest clinical TAO (36). Thyroid dysfunction appears to occur more frequently in patients with antecedent anti-TPO antibodies (36,37) and is often irreversible (33). IL-2 administration can also result in hypothyroidism likely via lymphocyte activation and secondary cytokine release (38,39). Surprisingly perhaps, INF-γ therapy does not culminate in autoimmune thyroid disease (40). The mechanisms through which systemic cytokines disrupt thyroid function have yet to be identified, but may be related to direct effects on iodine organification. Alternatively, they may enhance auto-antibody generation (38,41,42).

The Role of Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of TAO

Orbital connective tissue remodeling in TAO results from cytokine-dependent fibroblast activation (43). A key feature of the histopathology found in TAO is the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronan. Infiltration of connective tissue and extra-ocular muscle with immunocompetent cells, such as T and B lymphocytes and mast cells drives the tissue reactivity in TAO (44,45). The T cell phenotype predominating the active phase remains controversial (46). Cytokines abundant in affected tissue have yet to be adequately characterized but TNF-α, IL-1α and INF-γ were detected (47). mRNA encoding TNF-α, IL-1β, INF-γ, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 could also be detected in muscle and orbital fat (48). Changes in the relative abundance of these cytokines during the disease course have been suggested but these are not convincingly documented.

In culture, fibroblasts from orbital tissue respond to several cytokines (49,50). The anatomic site-selective involvement of the orbit appears to be based, at least in part, on the unusual susceptibility of orbital fibroblasts to pro-inflammatory molecules. When they are treated with IL-1β or leukoregulin, a T cell–derived cytokine, expression of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase (PGHS)-2 is up-regulated in orbital fibroblasts (49,51) and results in increased prostaglandin (PG)E2 production. While cytokines modestly increase PGHS-2 gene transcription, they more substantially enhance PGHS-2 mRNA stability. The induction of PGE2 by IL-1β is blocked by INF-γ and IL-4 (52). This surprising result suggests that despite the transition from Th1 to Th2 predominance as TAO progresses from the active to chronic phase, modulation by these cytokines could be maintained.

The impact of PGE2 on immunity is currently debated, but the prostanoid biases naïve (Th0) T cell development toward the Th2 phenotype at the expense of Th1-type cells (53). This would shift the profile of cytokines synthesized from IFN-γ responses to those mediated by IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. PGE2 also influences B cell and mast cell development. Th1 cytokines appear to predominate in active disease while Th2 may characterize late (chronic and stable) TAO (54,55). Furthermore, Xia et al. (56) found a correlation between Th1 dominance and the clinical activity score (CAS).

Like thyrocytes, orbital fibroblasts express high levels of CD40. This receptor is displayed on the cell surface (57), and its levels are induced by IFN-γ. When CD40 is ligated with its cognate ligand, CD154, signal transduction cascades are activated, leading to the up-regulation of specific downstream genes (57,58), including IL-6, IL-8, PGHS-2, and hyaluronan synthesis. Orbital fibroblasts from patients with GD proliferate when incubated with autologous T cells, an effect dependent on CD40–CD154 signaling (46). The CD40–CD154 bridge has been a major focus in the quest for effective therapy of many diseases. Its interruption may represent a therapeutic strategy for chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Recently, fibroblasts, like thyrocytes, were shown to express high levels of the T cell chemoattractants IL-16 and RANTES when activated by cytokines like IL-1β (59). In a subsequent study, IgG isolated from patients with GD (GD-IgG) induced particularly high levels of both IL-16 and RANTES in fibroblasts of these same donors (60). Based on the results of these studies, the fibroblast may be a key site for the expression of T cell–activating cytokines, and GD-IgG may act on fibroblasts to initiate T cell trafficking to affected tissues. A recent observation concerns the identity of the self-antigen recognized by GD-IgG. Pritchard and colleagues (61) found that these IgGs bind to the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), leading to the activation of fibroblasts. Thus, it appears that a second autoantigen, the IGF-1R may be involved in the pathogenesis of GD.

Cytokines As Potential Therapeutic Targets

Elevation in the levels of abundant cytokines in thyroid and orbital tissues in GD provides a rationale for exploring the therapeutic benefit that disrupting the relevant pathways might yield. Yet virtually no well-controlled and sufficiently powered studies have been conducted despite the availability of several cytokine-disrupting agents. A case might be made for blocking the TNF-α pathway, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by monocytes, macrophages, and T lymphocytes. TNF-α protein and mRNA appear to be over-expressed in orbital connective tissue in TAO (47,62). This cytokine can induce intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 expression in orbital fibroblasts (63). Moreover, serum levels are elevated in patients with hyperthyroid GD although they normalize following restoration of the euthyroid state (64). A polymorphism in the TNF-α gene promoter has been associated with increased incidence of GD (65,66). Thus, targeting TNF-α signaling might prove clinically useful for GD, particularly in cases of troublesome TAO. Three Food and Drug Administration–approved TNF-α inhibitors, each with a distinct mechanism of action, are currently available. These have revolutionized the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. Paridaens et al. (67), in a prospective but uncontrolled study, examined the effects of etanercept in patients with GD. This TNF-α inhibitor was administered to 10 euthyroid patients with active TAO. Prior to therapy, subjects had a mean CAS of 4. Following 12 weeks of anti-cytokine therapy, the mean CAS improved to 1.6. The majority of clinical improvement involved the soft tissues. The degree of proptosis was unaffected. Overall, 60% of the subjects reported moderate to marked improvement. Durrani et al. (68) report a single patient presenting with sight-threatening TAO who appeared to benefit from infliximab treatment. Despite a potentially central role in the pathogenesis of TAO, no studies examining the potential therapeutic benefits of interrupting the IL-1β pathway have as yet been reported. This cytokine elicits a number of responses in orbital fibroblasts and thyrocytes (10,51,63,69). Furthermore, it can be detected in the autoimmune thyroid gland (70) and orbital tissues in TAO (62). Chen et al. (71) studied 95 subjects with GD and 163 healthy controls and found an IL-1β gene promoter polymorphism that was associated with GD. Anakinra represents a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist used successfully to treat patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, although no convincing evidence currently supports their use, agents targeting TNF-α and IL-1β would appear to be good therapeutic candidates for TAO.

Summary

Altered actions and levels of several cytokines have been reported in GD and TAO. Nonetheless, little understanding currently exists concerning their specific roles in disease pathogenesis. Additional studies into the complex interplay between cytokines, residential cells and “professional” immune cells recruited to the thyroid and orbit in GD should provide additional clues as to how these molecular networks provoke and sustain disease. Cytokines and their receptors continue to represent potentially attractive targets for therapeutic intervention in aggressive and sight-threatening forms of TAO.

Acknowledgments

We thank Debbie Hanaya for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants RR017304, EY008976, EY011708, and DK063121.

References

- 1.Kim CH. Chemokine-chemokine receptor network in immune cell trafficking. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2004;4:343–361. doi: 10.2174/1568008043339712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianoukakis AG. Smith TJ. The role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of endocrine disease. Canadian Diabetes Journal. 2004;28:20–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tezuka H. Eguchi K. Fukuda T. Otsubo T. Kawabe Y. Ueki Y. Matsunaga M. Shimomura C. Nakao H. Ishikawa N, et al. Natural killer and natural killer-like cell activity of peripheral blood and intrathyroidal mononuclear cells from patients with Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:702–707. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-4-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Totterman TH. Andersson LC. Hayry P. Evidence for thyroid antigen-reactive T lymphocytes infiltrating the thyroid gland in Graves' disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 1979;11:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1979.tb03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stassi G. Di Liberto D. Todaro M. Zeuner A. Ricci-Vitiani L. Stoppacciaro A. Ruco L. Farina F. Zummo G. De Maria R. Control of target cell survival in thyroid autoimmunity by T helper cytokines via regulation of apoptotic proteins. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:483–488. doi: 10.1038/82725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsiades N. Poulaki V. Mitsiades CS. Koutras DA. Chrousos GP. Apoptosis induced by FasL and TRAIL/Apo2L in the pathogenesis of thyroid diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:384–390. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura Y. Watanabe M. Matsuzuka F. Maruoka H. Miyauchi A. Iwatani Y. Intrathyroidal CD4+ T lymphocytes express high levels of Fas and CD4+ CD8+ macrophages/dendritic cells express Fas ligand in autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid. 2004;14:819–824. doi: 10.1089/thy.2004.14.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S. Fazle Akbar SM. Zhen Z. Luo Y. Deng L. Huang H. Chen L. Li W. Analysis of the expression of Fas, FasL and Bcl-2 in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disorders. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aust G. Scherbaum WA. Expression of cytokines in the thyroid: thyrocytes as potential cytokine producers. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1996;104(Suppl 4):64–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gianoukakis AG. Martino LJ. Horst N. Cruikshank WW. Smith TJ. Cytokine-induced lymphocyte chemoattraction from cultured human thyrocytes: evidence for interleukin-16 and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted expression. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2856–2864. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gianoukakis AG. Douglas RS. King CS. Cruikshank WW. Smith TJ. Immunoglobulin G from patients with Graves' disease induces interleukin-16 and RANTES expression in cultured human thyrocytes: a putative mechanism for T-cell infiltration of the thyroid in autoimmune disease. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1941–1949. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weetman AP. Cellular immune responses in autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2004;61:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laberge S. Cruikshank WW. Kornfeld H. Center DM. Histamine-induced secretion of lymphocyte chemoattractant factor from CD8+ T cells is independent of transcription and translation. Evidence for constitutive protein synthesis and storage. J Immunol. 1995;155:2902–2910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schall TJ. Bacon K. Toy KJ. Goeddel DV. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature. 1990;347:669–671. doi: 10.1038/347669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonelli A. Rotondi M. Ferrari SM. Fallahi P. Romagnani P. Franceschini SS. Serio M. Ferrannini E. INF-gamma-inducible alpha-chemokine CXCL10 involvement in Graves' ophthalmopathy: modulation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:614–620. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Lopez MA. Sancho D. Sanchez-Madrid F. Marazuela M. Thyrocytes from autoimmune thyroid disorders produce the chemokines IP-10 and Mig and attract CXCR3+ lymphocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5008–5016. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romagnani P. Annunziato F. Lasagni L. Lazzeri E. Beltrame C. Francalanci M. Uguccioni M. Galli G. Cosmi L. Maurenzig L. Baggiolini M. Maggi E. Romagnani S. Serio M. Cell cycle-dependent expression of CXC chemokine receptor 3 by endothelial cells mediates angiostatic activity. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:53–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI9775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romagnani P. Rotondi M. Lazzeri E. Lasagni L. Francalanci M. Buonamano A. Milani S. Vitti P. Chiovato L. Tonacchera M. Bellastella A. Serio M. Expression of IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 in the thyroid and increased levels of IP-10/CXCL10 in the serum of patients with recent-onset Graves' disease. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:195–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64171-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonelli A. Fallahi P. Rotondi M. Ferrari SM. Romagnani P. Grosso M. Ferrannini E. Serio M. Increased serum CXCL10 in Graves' disease or autoimmune thyroiditis is not associated with hyper- or hypothyroidism per se, but is specifically sustained by the autoimmune, inflammatory process. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:651–658. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith TJ. Sciaky D. Phipps RP. Jennings TA. CD40 expression in human thyroid tissue: evidence for involvement of multiple cell types in autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Thyroid. 1999;9:749–755. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metcalfe RA. McIntosh RS. Marelli-Berg F. Lombardi G. Lechler R. Weetman AP. Detection of CD40 on human thyroid follicular cells: analysis of expression and function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1268–1274. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomer Y. Concepcion E. Greenberg DA. A C/T single-nucleotide polymorphism in the region of the CD40 gene is associated with Graves' disease. Thyroid. 2002;12:1129–1135. doi: 10.1089/105072502321085234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson EM. Concepcion E. Oashi T. Tomer Y. A Graves' disease-associated Koxak sequence single-nucleotide polymorphism enhances the efficiency of CD40 gene translation: a case for translational pathophysiology. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2684–2691. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen AK. Cytokine actions on the thyroid gland. Dan Med Bull. 2000;47:94–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajjan RA. Watson PF. Weetman AP. Cytokines and thyroid function. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1996;6:359–386. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(97)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato K. Satoh T. Shizume K. Ozawa M. Han DC. Imamura H. Tsushima T. Demura H. Kanaji Y. Ito Y, et al. Inhibition of 125I organification and thyroid hormone release by interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and INF-gamma in human thyrocytes in suspension culture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:1735–1743. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-6-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamazaki K. Kanaji Y. Shizume K. Yamakawa Y. Demura H. Kanaji Y. Obara T. Sato K. Reversible inhibition by interferons alpha and beta of 125I incorporation and thyroid hormone release by human thyroid follicles in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1439–1441. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.5.8077347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerard AC. Boucquey M. van den Hove MF. Colin IM. Expression of TPO and ThOXs in human thyrocytes is downregulated by IL-1alpha/IFN-gamma, an effect partially mediated by nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E242–253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajjan RA. Watson PF. Findlay C. Metcalfe RA. Crisp M. Ludgate M. Weetman AP. The sodium iodide symporter gene and its regulation by cytokines found in autoimmunity. J Endocrinol. 1998;158:351–358. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1580351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krogh Rasmussen A. Bech K. Feldt-Rasmussen U. Poulsen S. Holten I. Ryberg M. Dinarello CA. Siersbaek-Nielsen K. Friis T. Bendtzen K. Interleukin-1 affects the function of cultured human thyroid cells. Allergy. 1988;43:435–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1988.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gianoukakis AG. Jennings TA. King CS. Sheehan CE. Hoa N. Heldin P. Smith TJ. Hyaluronan accumulation in thyroid tissue: evidence for contributions from epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2007;148:54–62. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawai Y. DeGroot LJ. Binding of human thyrotropin receptor peptides to a Graves' disease-predisposing human leukocyte antigen class II molecule. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1176–1179. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh LK. Greenspan FS. Yeo PP. Interferon-alpha induced thyroid dysfunction: three clinical presentations and a review of the literature. Thyroid. 1997;7:891–896. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roti E. Minelli R. Giuberti T. Marchelli S. Schianchi C. Gardini E. Salvi M. Fiaccadori F. Ugolotti G. Neri TM. Braverman LE. Multiple changes in thyroid function in patients with chronic active HCV hepatitis treated with recombinant interferon-alpha. Am J Med. 1996;101:482–487. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bohbot NL. Young J. Orgiazzi J. Buffet C. Francois M. Bernard-Chabert B. Lukas-Croisier C. Delemer B. Interferon-alpha-induced hyperthyroidism: a three-stage evolution from silent thyroiditis towards Graves' disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:367–372. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carella C. Mazziotti G. Amato G. Braverman LE. Roti E. Clinical review 169: interferon-alpha-related thyroid disease: pathophysiological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3656–3661. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marazuela M. Garcia-Buey L. Gonzalez-Fernandez B. Garcia-Monzon C. Arranz A. Borque MJ. Moreno-Otero R. Thyroid autoimmune disorders in patients with chronic hepatitis C before and during interferon-alpha therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 1996;44:635–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.751768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartzentruber DJ. White DE. Zweig MH. Weintraub BD. Rosenberg SA. Thyroid dysfunction associated with immunotherapy for patients with cancer. Cancer. 1991;68:2384–2390. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911201)68:11<2384::aid-cncr2820681109>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krouse RS. Royal RE. Heywood G. Weintraub BD. White DE. Steinberg SM. Rosenberg SA. Schwartzentruber DJ. Thyroid dysfunction in 281 patients with metastatic melanoma or renal carcinoma treated with interleukin-2 alone. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1995;18:272–278. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Metz J. Romijn JA. Endert E. Corssmit EP. Sauerwein HP. Administration of interferon-gamma in healthy subjects does not modulate thyroid hormone metabolism. Thyroid. 2000;10:87–91. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preziati D. La Rosa L. Covini G. Marcelli R. Rescalli S. Persani L. Del Ninno E. Meroni PL. Colombo M. Beck-Peccoz P. Autoimmunity and thyroid function in patients with chronic active hepatitis treated with recombinant interferon alpha-2a. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;132:587–593. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1320587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fentiman IS. Balkwill FR. Thomas BS. Russell MJ. Todd I. Bottazzo GF. An autoimmune aetiology for hypothyroidism following interferon therapy for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:1299–1303. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith TJ. Fibroblast biology in thyroid diseases. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2002;9:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Trieb K. Sztankay A. Holter W. Anderl H. Wick G. Retrobulbar T cells from patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy are CD8+ and specifically recognize autologous fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2738–2743. doi: 10.1172/JCI117289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Carli M. D'Elios MM. Mariotti S. Marcocci C. Pinchera A. Ricci M. Romagnani S. del Prete G. Cytolytic T cells with Th1-like cytokine profile predominate in retroorbital lymphocytic infiltrates of Graves' ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1120–1124. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.5.8077301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldon SE. Park DJ. O'Loughlin CW. Nguyen VT. Landskroner-Eiger S. Chang D. Thatcher TH. Phipps RP. Autologous T-lymphocytes stimulate proliferation of orbital fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3913–3921. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heufelder AE. Bahn RS. Detection and localization of cytokine immunoreactivity in retro-ocular connective tissue in Graves' ophthalmopathy. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiromatsu Y. Yang D. Bednarczuk T. Miyake I. Nonaka K. Inoue Y. Cytokine profiles in eye muscle tissue and orbital fat tissue from patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1194–1199. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang HS. Cao HJ. Winn VD. Rezanka LJ. Frobert Y. Evans CH. Sciaky D. Young DA. Smith TJ. Leukoregulin induction of prostaglandin-endoperoxide H synthase-2 in human orbital fibroblasts. An in vitro model for connective tissue inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22718–22728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith TJ. Wang HS. Evans CH. Leukoregulin is a potent inducer of hyaluronan synthesis in cultured human orbital fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C382–388. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.2.C382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han R. Tsui S. Smith TJ. Up-regulation of prostaglandin E2 synthesis by interleukin-1beta in human orbital fibroblasts involves coordinate induction of prostaglandin-endoperoxide H synthase-2 and glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E2 synthase expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16355–16364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han R. Smith TJ. T helper type 1 and type 2 cytokines exert divergent influence on the induction of prostaglandin E2 and hyaluronan synthesis by interleukin-1beta in orbital fibroblasts: implications for the pathogenesis of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Endocrinology. 2006;147:13–19. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phipps RP. Stein SH. Roper RL. A new view of prostaglandin E regulation of the immune response. Immunol Today. 1991;12:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90064-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakelkamp IM. Bakker O. Baldeschi L. Wiersinga WM. Prummel MF. TSH-R expression and cytokine profile in orbital tissue of active vs. inactive Graves' ophthalmopathy patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2003;58:280–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Avunduk AM. Avunduk MC. Pazarli H. Oguz V. Varnell ED. Kaufman HE. Aksoy F. Immunohistochemical analysis of orbital connective tissue specimens of patients with active Graves ophthalmopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:631–638. doi: 10.1080/02713680591005931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia N. Zhou S. Liang Y. Xiao C. Shen H. Pan H. Deng H. Wang N. Li QQ. CD4+ T cells and the Th1/Th2 imbalance are implicated in the pathogenesis of Graves' ophthalmopathy. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sempowski GD. Rozenblit J. Smith TJ. Phipps RP. Human orbital fibroblasts are activated through CD40 to induce proinflammatory cytokine production. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C707–714. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao HJ. Wang HS. Zhang Y. Lin HY. Phipps RP. Smith TJ. Activation of human orbital fibroblasts through CD40 engagement results in a dramatic induction of hyaluronan synthesis and prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-2 expression. Insights into potential pathogenic mechanisms of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29615–29625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sciaky D. Brazer W. Center DM. Cruikshank WW. Smith TJ. Cultured human fibroblasts express constitutive IL-16 mRNA: cytokine induction of active IL-16 protein synthesis through a caspase-3-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;164:3806–3814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pritchard J. Horst N. Cruikshank W. Smith TJ. Igs from patients with Graves' disease induce the expression of T cell chemoattractants in their fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2002;168:942–950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pritchard J. Han R. Horst N. Cruikshank WW. Smith TJ. Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant expression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves' disease is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway. J Immunol. 2003;170:6348–6354. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar S. Bahn RS. Relative overexpression of macrophage-derived cytokines in orbital adipose tissue from patients with graves' ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4246–4250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cawood TJ. Moriarty P. O'Farrelly C. O'Shea D. The effects of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin1 on an in vitro model of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy; contrasting effects on adipogenesis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:395–403. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diez JJ. Hernanz A. Medina S. Bayon C. Iglesias P. Serum concentrations of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble TNF-alpha receptor p55 in patients with hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism before and after normalization of thyroid function. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2002;57:515–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simmonds MJ. Heward JM. Howson JM. Foxall H. Nithiyananthan R. Franklyn JA. Gough SC. A systematic approach to the assessment of known TNF-alpha polymorphisms in Graves' disease. Genes Immun. 2004;5:267–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shiau MY. Huang CN. Yang TP. Hwang YC. Tsai KJ. Chi CJ. Chang YH. Cytokine promoter polymorphisms in Taiwanese patients with Graves' disease. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paridaens D. van den Bosch WA. van der Loos TL. Krenning EP. van Hagen PM. The effect of etanercept on Graves' ophthalmopathy: a pilot study. Eye. 2005;19:1286–1289. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Durrani OM. Reuser TQ. Murray PI. Infliximab: a novel treatment for sight-threatening thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Orbit. 2005;24:117–119. doi: 10.1080/01676830590912562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gianoukakis AG. Cao HJ. Jennings TA. Smith TJ. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase expression in human thyroid epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C701–708. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ajjan RA. Weetman AP. Cytokines in thyroid autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2003;36:351–359. doi: 10.1080/08916930310001603046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen RH. Chen WC. Chang CT. Tsai CH. Tsai FJ. Interleukin-1-beta gene, but not the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene, is associated with Graves' disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 2005;19:133–138. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]