Abstract

Introduction

HJURP (Holliday Junction Recognition Protein) is a newly discovered gene reported to function at centromeres and to interact with CENPA. However its role in tumor development remains largely unknown. The goal of this study was to investigate the clinical significance of HJURP in breast cancer and its correlation with radiotherapeutic outcome.

Methods

We measured HJURP expression level in human breast cancer cell lines and primary breast cancers by Western blot and/or by Affymetrix Microarray; and determined its associations with clinical variables using standard statistical methods. Validation was performed with the use of published microarray data. We assessed cell growth and apoptosis of breast cancer cells after radiation using high-content image analysis.

Results

HJURP was expressed at higher level in breast cancer than in normal breast tissue. HJURP mRNA levels were significantly associated with estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), Scarff-Bloom-Richardson (SBR) grade, age and Ki67 proliferation indices, but not with pathologic stage, ERBB2, tumor size, or lymph node status. Higher HJURP mRNA levels significantly decreased disease-free and overall survival. HJURP mRNA levels predicted the prognosis better than Ki67 proliferation indices. In a multivariate Cox proportional-hazard regression, including clinical variables as covariates, HJURP mRNA levels remained an independent prognostic factor for disease-free and overall survival. In addition HJURP mRNA levels were an independent prognostic factor over molecular subtypes (normal like, luminal, Erbb2 and basal). Poor clinical outcomes among patients with high HJURP expression were validated in five additional breast cancer cohorts. Furthermore, the patients with high HJURP levels were much more sensitive to radiotherapy. In vitro studies in breast cancer cell lines showed that cells with high HJURP levels were more sensitive to radiation treatment and had a higher rate of apoptosis than those with low levels. Knock down of HJURP in human breast cancer cells using shRNA reduced the sensitivity to radiation treatment. HJURP mRNA levels were significantly correlated with CENPA mRNA levels.

Conclusions

HJURP mRNA level is a prognostic factor for disease-free and overall survival in patients with breast cancer and is a predictive biomarker for sensitivity to radiotherapy.

Introduction

The centromere has long been recognized as a locus important for proper cell division and accurate partitioning of chromosomes into daughter cells [1-3]. Centromeres are the chromatin regions associated with kinetochores, which are massive multi-protein complexes that mediate chromosome segregation and the mitotic checkpoint [4]. There is mounting evidence that kinetochores become functionally unstable during oncogenesis resulting in segregation defects, chromosome instability, and cancer development [4-6].

Holliday Junction Recognition Protein (HJURP, also known as hFLEG1), which is a newly discovered gene, was reported to be overexpressed in lung cancer cells through genome-wide expression profile analysis [7]. By quantitative RT-PCR, Valente et al found that the HJURP expression levels significantly differ between glioblastoma resection tumor and non-neoplastic white matter [8]. Additionally it was observed that the expression level of HJURP in glioblastoma was changed about nine fold compared to typically benign pilocytic astrocytomas by microarray profile analysis [9]. It has also been reported that HJURP is involved in DNA double-strand break repair pathway through interaction with MSH5 and NBS1 [7]. Recently two groups have shown that HJURP functions at the level of the centromere, and is required for centromere protein A (CENPA) centromeric localization, for loading of new CENPA nucleosomes, and for accurate chromosomal segregation [10-12]. A majority of cancer cells tend to gain and lose chromosomes at each mitotic division and are found to be aneuploid and chromosomally instable. Thus these findings support the hypothesis that alterations in HJURP might play an important role in cancer development. We investigated whether altered expression levels of HJURP are associated with adverse clinical outcomes using cohorts of patients with breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell lysates

The names of cell lines used in our investigations are listed in Table 1. The derivation, sources, and maintenance of most of the breast cancer cell lines used in this study have been reported previously [13] or were provided in Table 2. These cell lines have been previously analyzed for genomic aberrations by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and for gene-expression profiles using Affymetrix microarrays (Santa Clara, CA, USA) [13]. The information on growth conditions of additional cell lines was listed in Table 2. Cells at 50% to 75% confluence were washed in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Then cells were extracted with a lysis buffer (containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 25 mM NaF, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 15 mM pyrophosphate, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium molybdate, 1% Nonidet-P40, 10 mg/ml leupeptin, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF). Cell lysates were then clarified by centrifugation and frozen at -80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad BCA protein assay kit (Cat# 23227, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA).

Table 1.

The list of breast cancer cell lines and immortalized non-malignant mammary epithelial cells used in these investigations.

| Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Set 4 | Set 5 | Set 6 | Set 7 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lane | Name | Lane | Name | Lane | Name | Lane | Name | Lane | Name | Lane | Name | Lane | Name |

| 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 | 1 | SKBR3 |

| 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A | 2 | MCF12A |

| 3 | 600MPE | 12 | MDAMB134 | 21 | BT483 | 30 | 184A1N4 | 39 | DU4475 | 48 | HCC1395 | 57 | MX-1 |

| 4 | AU565 | 13 | MDAMB157 | 22 | HCC70 | 31 | 184B5 | 40 | SUM1315M02 | 49 | HCC1428 | 58 | SUM102 |

| 5 | BT20 | 14 | MDAMB175 | 23 | HCC1187 | 32 | HCC38 | 41 | HCC1954 | 50 | HCC1806 | 59 | SUM190 |

| 6 | BT474 | 15 | MDAMB231 | 24 | HCC1500 | 33 | HCC202 | 42 | SUM44PE | 51 | HCC1937 | 60 | HCC1419 |

| 7 | BT549 | 16 | MDAMB361 | 25 | MCF10A | 34 | HCC1143 | 43 | SUM52PE | 52 | HCC2185 | 61 | HCC3153 |

| 8 | CAMA1 | 17 | MDAMB415 | 26 | MDAMB453 | 35 | HCC1569 | 44 | SUM149PT | 53 | HCC2218 | 62 | S1 |

| 9 | HBL100 | 18 | MDAMB435 | 27 | ZR751 | 36 | HCC1599 | 45 | SUM159PT | 54 | HCC1599 | 63 | T4 |

| 10 | Hs578T | 19 | T47D | 28 | ZR7530 | 37 | LY2 | 46 | SUM185PE | 55 | UACC893 | 64 | MDAMB231-Gray |

| 11 | MCF7 | 20 | UACC812 | 29 | ZR75B | 38 | SUM225 | 47 | SUM225CWN | 56 | SUM229 | 65 | MDAMB231-ATCC |

Table 2.

Additional cell line growth conditions and subtypes

| Lane | Name | Subtype* | Medium | Culture condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 184A1N4 | N | MEGMa | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 31 | 184B5 | N | MEGMa | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 36 | HCC1599 | Basal A | RPMI1640+10%FBSb | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 48 | HCC1395 | Basal B | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 50 | HCC1806 | Basal A | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 53 | HCC2218 | Luminal | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 54 | HCC1599 | Basal A | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 55 | UACC893 | Luminal | DMEM+10% FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 56 | SUM229PE | N/A | Ham's F12+5% FBS+IHc | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 57 | MX-1 | N/A | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 58 | SUM102PT | Basal A | Ham's F12+IHEd | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 60 | HCC1419 | Luminal | RPMI1640+10%FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 62 | S1 | N | H14 medium +10 ng/ml EGF | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 63 | T4 | Basal B | H14 mediume | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 64 | MDAMB231-Gray | Basal B | DMEM+10% FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

| 65 | MDAMB231-ATCC | Basal B | DMEM+10% FBS | 37°C, 5% CO2 |

a: Clonetics MEBM (no Bi Carbonate)+Insulin(5 ug/ml)+Transferrin(5 ug/ml)+Hydrocortisone(0.5 ug/ml) +EGF(5 ng/ml) +Isoprorternol

b: Fetal bovine serum (FBS)

c: Ham's F12 + 5% FBS + IH {insulin (5 ug/ml) + Hydrocortisone (1 ug/ml) + HEPES (10 mM)}

d: Ham's F12 + IHE {insulin (5 ug/ml) + HEPES (10 mM) + EGF (10 ng/ml)}

e: H14 medium: DMEM/F12 (GIBCO/BRL) with 250 ng/ml insulin, 10 μg/ml transferrin, 2.6 ng/ml sodium selenite, 10-10 M estradiol, 1.4 × 10-6 M

*: N: non-malignant(immortalized), N/A: no data

Western blot

For Western blots, 10 μg of protein extracts per lane were electrophoresed with denaturing sodium doedecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels (4% to 12%), transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), and incubated with HJURP antibody 1:500 (Rabbit, HPA008436, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and actin (goat, sc-1616, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted with blocking buffer (927-40000, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) The membranes were washed four times with TBST and treated with 1:10,000 dilution of Alex Fluor 680 donkey anti-rabbit (A10043, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and IRDye 800CW conjugated donkey anti-goat (611-731-127, Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA) to detect HJURP and actin respectively. The signals were detected by infrared imaging (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Images were recorded as TIFF files for quantification.

Protein quantification

Protein levels were measured by quantifying infrared imaging recorded from labeled antibodies using Scion Image [14]. For each protein, the blots were made for 7 sets of 11 cell lines, each set including the same pair (SKBR3 and MCF12A) to permit intensity normalization across sets. A basic multiplicative normalization was carried out by fitting a linear mixed effects model to log intensity values, and adjusting within each set to equalize the log intensities of the pair of reference cell lines across the sets.

Tumor samples

Detailed patient information has been described in our previous studies [15]. This analysis is based on previously reported comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and a gene expression profile of 130 tumors from UC San Francisco and the California Pacific Medical Center collected between 1989 and 1997.

Validation

The association of HJURP expression levels and survival among patients with breast tumors was examined in existing microarray data sets of primary tumor samples that had been profiled with an Affymetrix microarray assay (either HG-U133A or HG U133 Plus 2.0) ((GEO:GSE1456), (GEO:GSE7390), (GEO:GSE2034), (GEO:GSE4922)) or Agilent oligo microarray (Santa Clara, CA, USA)(Table 3). Probe 218726_at and 20366 (GenBank: NM_018410) were used to measure HJURP expression in Affymetrix and Agilent GeneChip, respectively. The process data from GEO website were downloaded for analysis.

Table 3.

Information of gene expression datasets used in this study

HJURP shRNA construct

The shRNA sequences were (forward) 5'-GATCCCC GAGCGATTCATCTTCATCA TTCAAGAGA TGATGAAGATGAATCGCTC TTTTTGGAAA-3' and (reverse) 5'-AGCT TTTCCAAAAA GAGCGATTCATCTTCATCA TCTCTTGAA TGATGAAGATGAATCGCTC GGG-3' synthesized from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). HJURP shRNA was cloned into BglII and HindIII cleavage sites of pSUPER.retro.puro vector based on manufactory's instruction (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA, USA). HJURP shRNA expression vector were confirmed by direct DNA sequencing.

Retroviral packaging and infection

HJURP shRNA (or empty) retroviral vectors along with packaging system pHit60 and pVSVG vectors were then co-transfected into the HEK 293 Phoenix ampho packaging cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) by using FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Roche, Lewes, UK) according to the instruction to produce retroviral supernatants. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the virus-containing supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. Retroviral infection was performed by adding filtered supernatant to a MDAMB231 cell line cultured on 10 cm dishes with 50% confluent in the presence 4 ug/ml of polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Six hours after infection, the medium was changed with fresh medium. After 48 hours, infected cells were selected by adding 5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) to the culture medium for 72 hours and then maintained in complete medium with 2 μg/ml puromycin. Down-regulation of HJURP expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

High content imaging to assess cell number and apoptotic cells

The effects on cell growth and apoptosis were assessed by a Cellomics high-content image screening system (Cellomics, Thermo Fisher Scientfic Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA) after breast cancer cells exposed to a single dose of 0 (sham), 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 or 10 Gy X-ray radiation emitted from an irradiator (model 43855F, Faxitron X-ray Corporation, Lincolnshire, IL, USA). Live cells in 96 well plates with six replicates from each treatment were stained with 1 μmol/L YO-PRO-1 positive cells.

Statistical analysis

Spearman's correlation coefficient and test were used to examine the relationship between HJURP mRNA level and its protein level in the cell line studies, and the relationship with age, tumor size in the tumor studies, and CENPA mRNA level. The association between HJURP mRNA level and clinical factors, such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), ERBB2 and lymph node status, pathological stage, Scarff-Bloom-Richardson (SBR) grade, was analyzed by Mann-Whitney U (for two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis H (for more than two groups) test. Kaplan-Meier plots were constructed and a long-rank test was used to determine differences among disease free and overall survival curves according to HJURP expression level or radiotherapy. Multivariate analyses were carried out to examine whether HJURP expression is an independent prognostic factor for survival when adjusting for other covariates (age, ER, PR, lymph node, pathologic stage, SBR grade, tumor size) or the molecular subtypes (normal like, luminal, Erbb2 and Basal) using Cox proportional-hazard regression. In addition, the relation between HJURP expression and survival was explored in microarray data sets by dividing the cases from each cohort into a group with high (top one-third), moderate (middle one-third), and low (bottom one-third) level of expression. All analyses were performed by SPSS 11.5.0 for Windows. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

HJURP is overexpressed in breast cancer

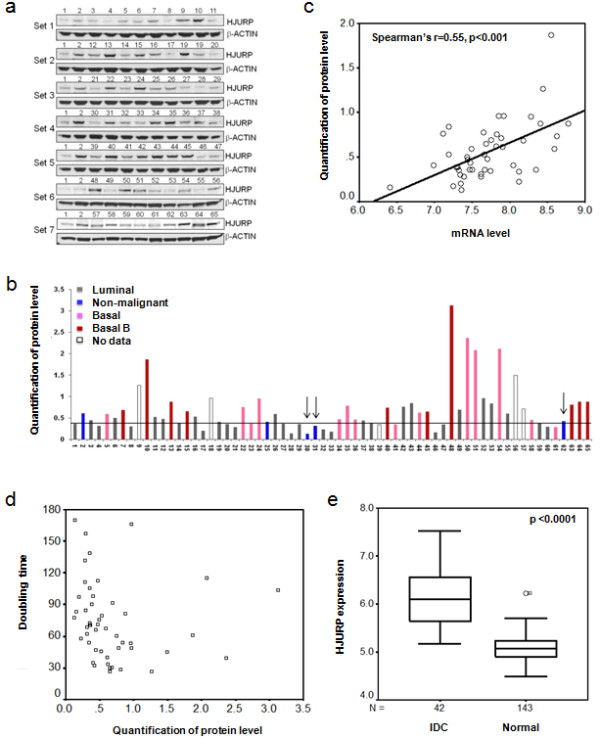

We examined the protein levels of HJURP in a large panel of human breast cancer cell lines and immortalized non-malignant mammary epithelial cells, which have been analyzed for genomic aberrations by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and for gene-expression profiles using Affymetrix microarrays [13]. Although we found few genetic alterations in the HJURP locus by inspection of these CGH microarray data, the protein levels of HJURP were elevated in about 50% of these breast cancer cell lines when compared to immortalized but non-malignant mammary epithelial cells 184A1N4, 184B5, and S1 (Figure 1a, b). In order to determine whether mRNA expression reflected protein levels, we quantified and normalized HJURP protein expression in each cell line and demonstrated a significant correlation between mRNA expression and protein levels (the Affymetrix probe for HJURP is 218726_at: Spearman's correlation coefficient R = 0.55, P < 0.001; Figure 1c). Next we examined whether HJURP protein level is associated with cell proliferation. In order to do so, we measured the doubling time for each cell line and found that the doubling time of cell lines was negatively correlated with HJURP protein levels (Spearman's correlation coefficient R = -0.395, P = 0.005; Figure 1d). Furthermore, HJURP mRNA levels in invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC) were statistically significantly higher than its levels in the normal breast ducts (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1e) [16].

Figure 1.

HJURP is overexpressed in human breast cancer cell lines and primary breast tumors. (a) Protein levels of HJURP (Holliday junction recognition protein) in a large panel of human breast cancer cell lines and immortalized non-malignant mammary epithelial cells were assessed by Western blotting. Samples 30, 31 and 62 are immortalized non-malignant mammary epithelial cells 184A1N4, 184B5 and S1 respectively. (b) Normalized quantification of HJURP protein levels in the cell lines using Scion Image software are shown. The arrows indicate the immortalized non-malignant mammary epithelial cells 184A1N4, 184B5, and S1 respectively. The line shows M+1.95*SE where M is mean of 184A1N4, 184B5 and S1 protein levels and SE is standard error of 184A1N4, 184B5 and S1 protein levels. Protein level above this line was defined as overexpression. About 50% breast cancer cell lines have overexpression of HJURP. (c) Figure 1c shows the correlation between mRNA and protein levels of HJURP in human breast cancer cell lines. HJURP expression is measured as log2 (probe intensities) by Affymetrix microarray. The detail for protein quantification refers to Materials and Methods. R was Spearman's rho correlation coefficient. The two-tailed P -value was obtained from Spearman correlation test. (d) The HJURP protein level has a negative and significant correlation with the doubling times of cell lines. (e) HJURP mRNA expression level is significantly evaluated in invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC) in comparison to normal breast ducts. HJURP mRNA expression is assessed by Affymetrix microarray. HJURP expression is measured as log2 (probe intensities). The microarray data were found in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database GEO accession numbers [GEO:GSE10780] [16].

HJURP mRNA level is an independent prognostic biomarker for poor clinical outcome

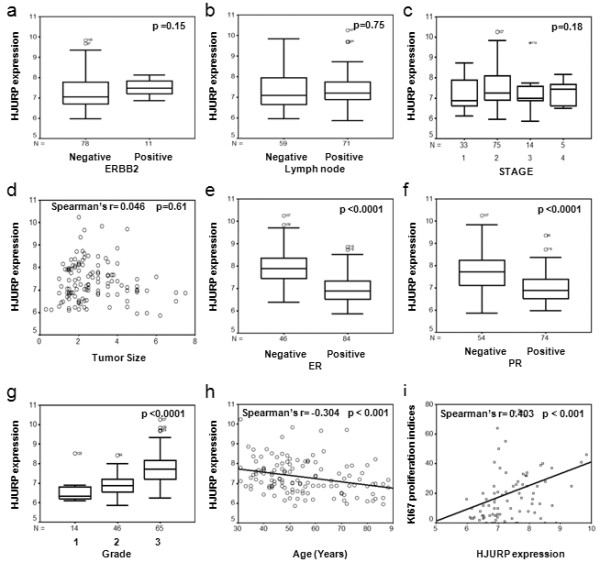

We assessed the association between HJURP mRNA levels and clinical factors and outcomes using a cohort of breast cancer patients in our previous studies [15]. HJURP expression level is measured as log2 (probe intensities) by Affymetrix microarray. In univariate analysis, HJURP mRNA levels were not associated with pathological stage, tumor size, ERBB2 positive, or lymph node positive status (Figure 2a, b, c, d). However, high HJURP mRNA levels were significantly associated with estrogen-receptor negative (ER-) (P < 0.0001), progesterone-receptor negative (PR-) P < 0.0001), advanced SBR grade (P < 0.0001), young age (P < 0.001) and Ki67 proliferation indices (P < 0.001) (Figure 2e, f, g, h, i). When we divided HJURP expression levels into three groups (low = bottom third, moderate = middle third, and high = top third), patients whose tumor with high HJURP expression levels had significantly shorter disease free survival (P = 0.0009) and overall survival (P = 0.0017) period using a Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis (Figure 3a). Interestingly, although HJURP expression significantly correlated with Ki67 proliferation indices, Ki67 proliferation indices are not significantly associated with both disease-free and overall survival (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Association of HJURP mRNA levels with clinic and pathological factors in patients with breast cancer. There was no significant association between HJUPR mRNA levels and (a) ERBB2 (erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2) status, or (b) lymph node status, or (c) pathological stage or (d) tumor size. There were significant higher mRNA levels of HJURP in (e) estrogen receptor (ER) negative patients, (f) progesterone receptor (PR) negative patients; higher mRNA levels of HJURP were significantly associated with (g) high SBR grade, (h) younger age, and (i) Ki67 proliferation indices. HJURP expression is measured as log2 (probe intensities) by Affymetrix microarray. The two-tailed P-values were obtained by Mann-Whitney U test for ERBB2, lymph node, ER and PR status, Kruskal-Wallis H test for pathological stage and SBR grade, and Spearman correlation for size, age, and Ki67 proliferation indices.

Figure 3.

The impact of HJURP expression and Ki67 proliferation indices on the disease-free and overall survival. Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves for breast cancer patients according to tumor expression of HJURP. The patients from each cohort were divided into a group with high (top one-third), moderate (middle one-third) and low (bottom one-third) level of HJURP expression. HJURP expression is measured log2 (probe intensities) as in the microarray. The same criteria were used for Ki67 proliferation indices. HJURP mRNA expression was a significant prognostic factor for disease-free and overall survival, whereas Ki67 proliferation indices were not significantly associated with prognosis. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for disease-free and overall survival are presented, while (b) shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for disease-free and overall survival based on Ki67 proliferation indices. The P-values shown were obtained from a long-rank test.

In multivariate analyses (including age, pathological stage, SBR grade, ER status, PR status, lymph node status, tumor size, HJURP mRNA levels), lymph node positive and high pathological stage were associated with poor disease free survival, whereas lymph node positive, big tumor size, and age were associated with poor overall survival (Table 4). HJURP expression level is an indicator of a poor prognosis for disease-free survival (hazard ratio, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.18 to 3.58; P = 0.011), and for overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.11 to 3.01; P = 0.018) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analysis of independent prognostic factors in patients with breast cancer using Cox regression

| Disease-Free survival | Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| HJURP expression+ | 2.05 (1.18 to 3.58) | 0.011 | 1.83 (1.11 to 3.01) | 0.018 |

| Lymph node (positive) | 3.76 (1.16 to 12.25) | 0.028 | 2.72 (1.08 to 6.88) | 0.035 |

| High Stage | 2.23 (1.08 to 4.59) | 0.030 | 1.85 (0.94 to 3.63) | 0.075 |

| Tumor size | 1.32 (0.97 to 1.79) | 0.079 | 1.34 (1.02 to 1.77) | 0.038 |

| Age (year) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.05) | 0.33 | 1.03 (1.004 to 1.053) | 0.022 |

| High SBR Grade | 0.76 (0.33 to 1.75) | 0.52 | 1.00 (0.50 to 2.00) | 0.99 |

| ER (positive) | 0.63 (0.21 to 1.94) | 0.42 | 0.86 (0.33 to 2.25) | 0.75 |

| PR (positive) | 0.90 (0.33 to 2.50) | 0.84 | 0.95 (0.40 to 2.26) | 0.91 |

+ HJURP expression is measured as log2 (probe intensities) by Affymetrix microarray

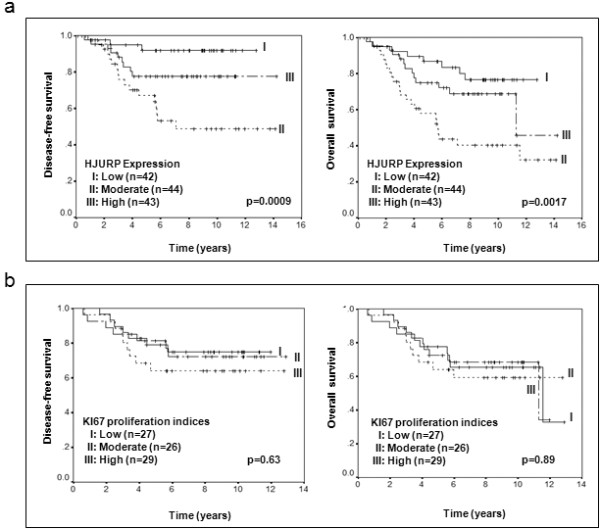

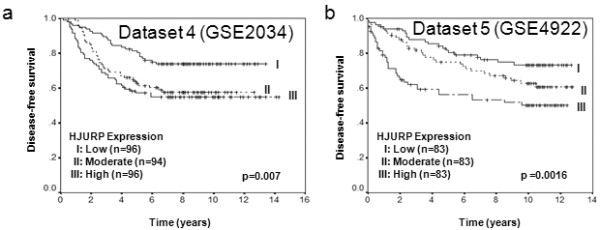

To validate our findings, we used several independent breast cancer cohorts with previously reported microarray data deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [17], to compare mRNA level of HJURP in tumor tissue with patient survival (Table 3). In agreement with our initial findings, decreased disease-free and overall survival rate was associated with high mRNA level of HJURP in all of the datasets (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Validation of the association between HUJRP mRNA and prognosis in three independent cohorts. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for breast cancer patients according to tumor expression of HJURP are shown. The patients from each cohort were divided into a group with high (top one-third), moderate (middle one-third) and low (bottom one-third) level of HJURP expression. HJURP expression is measured log2 (probe intensities) as in the microarray. The significant association between HJURP mRNA and disease-free and overall survival was validated in three independent cohorts of patients with breast cancer. Parts (a), (b) and (c) show the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for disease-free and overall survival in Dataset 1 (GSE1456), Dataset 2 (GSE7390) and Dataset 3 (NKI) respectively. The P-values shown were obtained from a long-rank test.

Figure 5.

Validation of the association between HJURP mRNA and disease-free survival in another two independent cohorts. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for breast cancer patients according to tumor expression of HJURP are shown. The patients from each cohort were divided into a group with high (top one-third), moderate (middle one-third) and low (bottom one-third) level of HJURP expression. HJURP expression is measured log2 (probe intensities) as in the microarray. The significant association between HJURP mRNA and disease-free survival was further validated in two independent cohorts of patients with breast cancer. Parts (a) and (b) show the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for disease-free survival in Dataset 4 (GSE2034) and Dataset 5 (GSE4922). The P-values shown were obtained from a long-rank test.

Finally, we investigated whether HJURP mRNA levels were an independent prognostic factor over molecular subtypes (normal like, luminal, Erbb2 and basal) using Cox regression. In order to do so, three data sets (reference 14, Dataset 1 and 3), in which the information of the molecular subtypes was available, were combined because there were few patients in each subtype using each data set. As showed in Table 5, both HJURP mRNA levels and molecular subtypes were independently significantly associated with survival.

Table 5.

Both HJURP mRNA levels and molecular subtypes are independent prognostic factors in patients with breast cancer using Cox regression#

| Disease-Free survival | Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| HJURP | 6.19E-07 | 0.00011 | ||

| High vs Low | 3.26 (2.01 to 5.28) | 1.72E-06 | 3.23 (1.85 to 5.62) | 3.65E-05 |

| Moderate vs Low | 3.34 (2.11 to 5.27) | 2.3E-07 | 2.89 (1.68 to 4.95) | 0.00012 |

| Molecular Subtypes | 0.0069 | 0.00012 | ||

#The results are obtained from the combination of three data sets (reference 14, Dataset 1 and 3) where the information of the molecular subtypes (Normal like, Luminal, Erbb2 and Basal) was available.

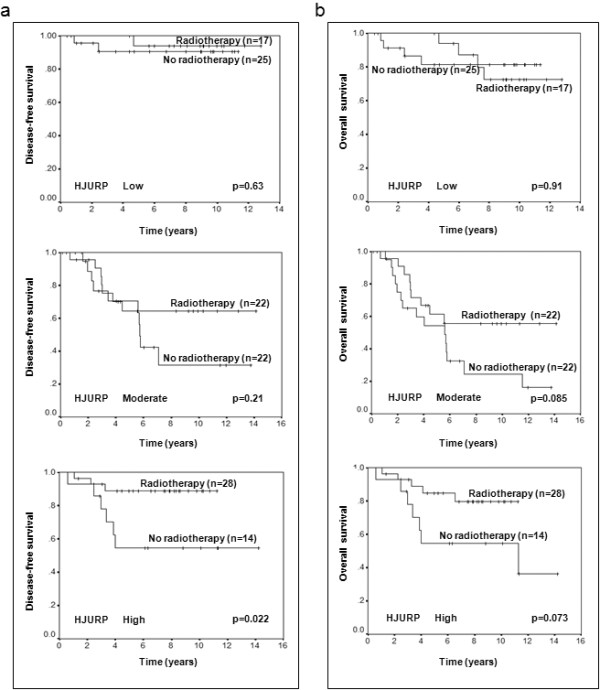

HJURP mRNA level predicts the sensitivity to radiation treatment in breast cancer patients and cell lines

It has been reported that HJURP is involved in the DNA repair pathway, thus next we investigated whether the HJURP mRNA level is a predictive marker for radiotherapy in our cohort of breast cancer patients. As shown in Figure 6a, the radiotherapy significantly increased disease-free survival of patients within the high HJURP mRNA level group (P = 0.022) whereas radiotherapy did not within the low HJURP mRNA level group. The data showed a trend toward increased overall survival within the high and moderate HJURP mRNA level group (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

The expression level of HJURP is a predictive factor for radiotherapy sensitivity. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for breast cancer patients according to radiotherapy treatment are presented. Part (a) shows the survival curves for disease-free survival, while (b) shows survival curves for overall survival. The P-values shown were obtained from a long-rank test.

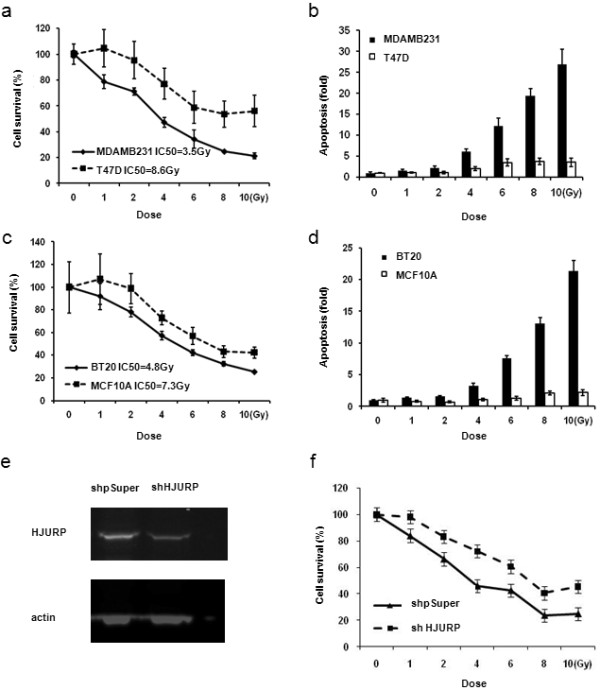

In order to confirm the relationship between HJURP mRNA levels and radiation sensitivity, we selected two cell lines, one had high levels of HJURP (MDAMB231), the other had a low level of HJURP (T47D), and treated them with different doses of x-ray irradiation. Seventy-two hours after radiation, we measured cell growth and apoptosis using high-content image analysis. Our data showed that the response to radiation in breast cancer cell line MDAMB231 (IC50 = 3.5 Gy) was more sensitive than T47D (IC50 = 8.6 Gy) (Figure 7a). Consistent with radiation sensitivity, MDAMB231 cells had ahigher rate of apoptosis than T47D cells (Figure 7b). Similar results were found in additional cell lines BT20 with high levels of HJURP and MCF10A with low levels of HJURP (Figure 7c, d). Finally we designed small interfering RNA (shRNA) against HJURP and generated stable transfectants in a human breast cancer cell line (MDAMB231). The shRNA down-regulated HJURP protein levels by 75%, as assessed by Western blotting assays (Figure 7e). Knockdown of the HJURP gene reduced the sensitivity to radiation (Figure 7f).

Figure 7.

The HJURP mRNA level in breast cancer cell lines predicts the sensitivity to radiation treatment. Part (a) shows the percent of viable cells at 72 hours after different doses of radiation in breast cancer cell line MDAMB231 with a high level of HJURP and T47D with a low level of HJURP. MDAMD231 cells are more sensitive to radiation treatment than T47D cells. Figure 7b shows the fold change of apoptosis in comparison to control (no radiation) at 72 hours after the different dose of radiation in breast cancer cell line MDAMB231 and T47D. There are more apoptosis in MDAMB231 cells than T47D cells. Part (c) shows the percent of viable cells at 72 hours after the different dose of radiation in breast cancer cell line BT20 with high level of HJURP and MCF10A with low level of HJURP. BT20 cells are more sensitive to radiation treatment than MCF10A cells. Part (d) shows the fold change of apoptosis in comparison to control (no radiation) at 72 hours after the different dose of radiation in breast cancer cell line BT20 and MCF10A. There are more apoptosis in BT20 cells than MCF10A cells. (e) HJURP protein levels are down-regulated by shRNA in MDAMB231 breast cancer cell lines. Part (f) shows that MDAMB231 breast cancer cells with shRNA against HJURP reduce the sensitivity to radiation.

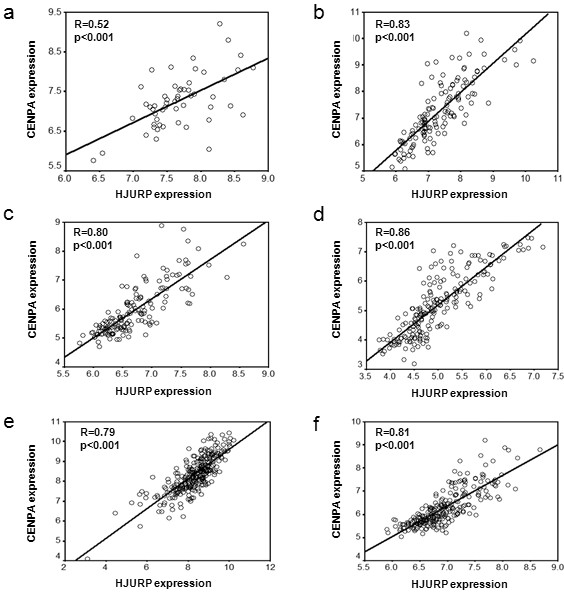

Co-overexpression of HJURP and CENPA in breast cancer

Recently it has been shown that HJURP interacts with CENPA for localization to centromeres and for accurate chromosome segregation. Thus we examined the expression pattern between HJURP and CENPA at the mRNA level. Surprisingly, HJURP levels were significantly and positively correlated with CENPA levels in human breast cancer cell lines (Figure 8a) and primary breast tumors (Figure 8b). Such highly significant correlation was confirmed in four independent cohorts with breast tumors (Figure 8c, d, e, f).

Figure 8.

Correlation between HJURP and CENPA in mRNA levels. There is a highly significant and positive correlation between HJURP and CENPA in mRNA levels within human breast cancer cell lines (a), Primary breast tumors (b), Dataset 1 (c), Dataset2 (d), Dataset4 (e), and Dataset5 (f). R shown is Spearman's rho correlation coefficient.

Discussion

The current study is the first to report that HJURP is overexpressed in breast cancer cell lines and primary human breast cancer compared to non-malignant human mammary epithelial cells and normal breast tissues. High HJURP mRNA expression is significantly associated with both shorter disease-free and overall survival which were validated in five independent clinical datasets for breast cancer. Furthermore, HJURP is a predictive marker for sensitivity of radiotherapy, indicating levels of HJURP mRNA and protein in breast cancer patients are clinically relevant.

Although we found HJURP mRNA levels were not associated with ERBB2 status, the mRNA levels of HJURP was still found significantly higher in triple-negative (ER negative, PR negative, ERBB2/HER2/neu not overexpressed) breast cancer, possibly due to the fact that a higher HJURP mRNA level is significantly associated with ER or PR negative status. Triple negative breast cancer has distinct clinical and pathological features, and also has relatively poor prognosis and aggressive behavior [18-20], consistent with our finding that high HJURP expression is associated with a bad prognosis. Furthermore, our studies showed that the prognostic effect of HJURP mRNA level on survival is independent of the clinical factors, such as age, lymph node, pathological stage, SBR grade, ER, PR, tumor size, and the molecular subtypes. In addition, we found there is a significant correlation between HJURP expression and Ki67 proliferation indices; however, HJURP expression is a better biomarker than Ki67 proliferation indices for the predication of prognosis.

It is very interesting to find that the HJURP mRNA level is a predictive marker for radiotherapy sensitivity. Our results showed that patients with low mRNA levels of HJURP already had a good prognosis and could not get further benefit from radiotherapy, suggesting these patients may not necessarily benefit from receiving radiotherapy. However, patients with high HJURP mRNA levels could increase their survival with radiotherapy, but they still had a worse prognosis than those with low levels as found in Dataset 3 (Figure 4c) and Dataset 4 (Figure 5a) where almost all patients received radiotherapy with or without additional benefit. Thus a high level of HJURP is overall associated with poor prognosis. Although we note our findings will require replication in additional independent and larger cohorts, our in vitro studies further confirmed that breast cancer cells with high levels of HJURP are more sensitive to radiation treatment, and even more convincingly, knock down of HJURP by shRNA reduces the sensitivity to radiation. The radiation induced more apoptosis in these cells, consistent with clinical findings. A previous report showed that HJURP interacts with proteins hMSH5 and NBS1, suggesting HJURP is involved in the DNA double-strand break repair process [7]. The understanding of the roles that HJURP plays in DNA repair and cell death in response to DNA damage may provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of breast tumor development and may help to improve breast cancer therapies. In addition, we found that cells with HJURP shRNA grew slowly (data not shown), which is consistent with the finding that the double time of cell lines was negatively correlated with HJURP protein level, indicating HJURP plays an important role in cell proliferation. Thus one of the reasons why the ability of HJURP to act as a marker for prognosis and response to radiotherapy may be linked to its control of cell proliferation.

HJURP has recently been reported to interact with CENP-A for the purpose of localizing CENP-A and loading new CENP-A nucleosomes on the centromere [11,12]. CENP-A is the key determinant of centromere formation and kinetochore assembly, which regulate the complex job of attaching chromosomes to the mitotic spindle; ensuring that those attachments are correct; signalling a delay in mitotic progression if they are not, and regulating the movements of the chromosomes towards the spindle poles in anaphase. Thus overexpression of HJURP in human breast cancer may be similar to overexpression of mitotic kinases, such as Aurora kinases, which induce genomic instability that is one of the hallmarks for tumor development. In this study we showed that HJURP mRNA levels are highly significantly correlated with CENPA mRNA levels in human breast cancer cell lines and primary breast tumors. Such correlation is also found in other types of human cancer, such as cancers from lung, ovary, prostate (data not shown), suggesting that compatible mRNA levels of HJURP and CENPA might be required for tumor progression. Further investigation of the interaction between HJURP and CENPA for breast cancer development will be carried out in our future studies.

Conclusions

The expression level of HJURP has an independent prognostic impact for both disease-free and overall survival in breast cancer, and is a predictive biomarker for radiotherapy. Further investigations of the mechanisms of HJURP in tumor development and its association with sensitivity to radiotherapy are clearly warranted.

Abbreviations

CENP-A: centromere protein A; CGH: Comparative Genomic Hybridization; ER: estrogen receptor; ERBB2: v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2: neuro/glioblastoma derived oncogene homolog; GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; HJURP: Holliday Junction Recognition Protein; PR: progesterone receptor; SBR grading: Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ZH and GH contributed equally. ZH, GH, SG, MP and NB performed in vitro studies. JHM and GH performed statistical analysis. AS and MEL provided microarray expression and survival data. JHM, EAB, ZH and JWG designed the study, and drafted and revised the paper. All authors read, commented, and approved the final manuscript.

See related editorial by Coates et al., http://breast-cancer-research.com/content/12/3/106

Contributor Information

Zhi Hu, Email: ZHu@lbl.gov.

Ge Huang, Email: GHuang2@lbl.gov.

Anguraj Sadanandam, Email: ASadanandam@lbl.gov.

Shenda Gu, Email: SGu2@lbl.gov.

Marc E Lenburg, Email: MELenburg@lbl.gov.

Melody Pai, Email: MPai@lbl.gov.

Nora Bayani, Email: NBayani@lbl.gov.

Eleanor A Blakely, Email: EABlakely@lbl.gov.

Joe W Gray, Email: JWGray@lbl.gov.

Jian-Hua Mao, Email: JHMao@lbl.gov.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant R01 CA116481 (JHM); by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Biological & Environmental Research, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants P50 CA 5820, the P30 CA 82103, and the U54 CA 112970 (JWG).

References

- Morris CA, Moazed D. Centromere assembly and propagation. Cell. 2007;128:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagnarelli P, Ribeiro SA, Earnshaw WC. Centromeres: old tales and new tools. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1950–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar GA, Amon A. Emerging roles for centromeres in meiosis I chromosome segregation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:899–910. doi: 10.1038/nrg2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Mao Y, Sullivan KF. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell. 2003;112:407–421. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves Dos Santos, Silva A, Sarkar R, Harizanova J, Guffei A, Mowat M, Garini Y, Mai S. Centromeres in cell division, evolution, nuclear organization and disease. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:2040–2058. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Sato N, Hayama S, Yamabuki T, Ito T, Miyamoto M, Kondo S, Nakamura Y, Daigo Y. Activation of Holliday junction recognizing protein involved in the chromosomal stability and immortality of cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8544–8553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente V, Teixeira SA, Neder L, Okamoto OK, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SK, Scrideli CA, Paçó-Larson ML, Carlotti CG Jr. Selection of suitable housekeeping genes for expression analysis in glioblastoma using quantitative RT-PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie SK, Okamoto OK, Uno M, Hasegawa AP, Oba-Shinjo SM, Cohen T, Camargo AA, Kosoy A, Carlotti CG Jr, Toledo S, Moreira-Filho CA, Zago MA, Simpson AJ, Caballero OL. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase transcript abundance correlates with malignancy grade in human astrocytomas. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:807–815. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Pulido L, Pidoux AL, Ponting CP, Allshire RC. Common ancestry of the CENP-A chaperones Scm3 and HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy EM, Roche D, Tagami H, Lacoste N, Ray-Gallet D, Nakamura Y, Daigo Y, Nakatani Y, Almouzni-Pettinotti G. HJURP is a cell-cycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell. 2009;137:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz DR, Jansen LE, Bailey AO, Yates JR III, Bassett EA, Wood S, Black BE, Cleveland DW. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, Clark L, Bayani N, Coppe JP, Tong F, Speed T, Spellman PT, DeVries S, Lapuk A, Wang NJ, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, McCormick F, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lippman M, Ethier S, Gazdar A, Gray JW. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scion Corporation Home Page. http://www.scioncorp.com Scion Corporation Home Page.

- Chin K, DeVries S, Fridlyand J, Spellman PT, Roydasgupta R, Kuo WL, Lapuk A, Neve RM, Qian Z, Ryder T, Chen F, Feiler H, Tokuyasu T, Kingsley C, Dairkee S, Meng Z, Chew K, Pinkel D, Jain A, Ljung BM, Esserman L, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, Gray JW. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DT, Nasir A, Culhane A, Venkataramu C, Fulp W, Rubio R, Wang T, Agrawal D, McCarthy SM, Gruidl M, Bloom G, Anderson T, White J, Quackenbush J, Yeatman T. Proliferative genes dominate malignancy-risk gene signature in histologically-normal breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:335–46. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Main Page. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Main page.

- Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, Rijn M van de, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Eystein Lønning P, Børresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C, Leung S, McKinney S, Chia SK, Perou CM, Nielsen TO. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1368–1376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Features and Patterns of Recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y, Bjöhle J, Amler L, Borg AL, Egyhazi S, Hall P, Han X, Holmberg L, Huang F, Klaar S, Liu ET, Miller L, Nordgren H, Ploner A, Sandelin K, Shaw PM, Smeds J, Skoog L, Wedrén S, Bergh J. Gene expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from adjuvant therapy: derived and validated in two population-based cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R953–964. doi: 10.1186/bcr1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmedt C, Piette F, Loi S, Wang Y, Lallemand F, Haibe-Kains B, Viale G, Delorenzi M, Zhang Y, d'Assignies MS, Bergh J, Lidereau R, Ellis P, Harris AL, Klijn JG, Foekens JA, Cardoso F, Piccart MJ, Buyse M, Sotiriou C. TRANSBIG Consortium. Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3207–3214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijver MJ van de, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, Velde T van der, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, Bernards R. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, Talantov D, Timmermans M, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Yu J, Jatkoe T, Berns EM, Atkins D, Foekens JA. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivshina AV, George J, Senko O, Mow B, Putti TC, Smeds J, Lindahl T, Pawitan Y, Hall P, Nordgren H, Wong JE, Liu ET, Bergh J, Kuznetsov VA, Miller LD. Genetic reclassification of histologic grade delineates new clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10292–10301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robustness, Scalability, and Integration of a Wound-Reponse Gene Expression Signature in Predicting Breast Cancer Survival. http://microarray-pubs.stanford.edu/wound_NKI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]