Abstract

We have previously reported the oncogenic properties of the gene ‘Amplified in Breast Cancer 1’ (AIB1), a member of the p160 family of hormone receptor coactivators. In a transgenic mouse model AIB1 overexpression resulted in a high incidence of tumors in various tissues, including mammary gland, uterus, lung, and pituitary. In order to determine whether AIB1’s oncogenicity in this model depended on its function as an estrogen receptor (ER) coactivator we abolished ER signaling through two independent approaches, by performing ovariectomy on AIB1 transgenic (AIB1-tg) mice to prevent gonadal estrogen production and by crossing AIB1-tg mice with ER null mutant mice. Ovariectomized mice, but not AIB1 × ERα−/− mice, still developed mammary gland hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. Both approaches, however, completely prevented the development of invasive mammary tumors, indicating that invasive mammary tumor formation is strictly estrogen-dependent. Once developed, AIB1-induced mammary tumors can subsequently lose their dependence on estrogen: Injection of ERα(+) tumor cell lines derived from such tumors into ovariectomized or untreated wild type mice resulted in a similar rate of tumor growth in both groups. Surprisingly, however, ovariectomized mice had a ~4-fold higher rate of metastasis formation, suggesting that estrogen provided some protection from metastasis formation. Lastly, our experiments identified oncogenic functions of AIB1 that are independent of its ER coactivation, as both approaches, ovariectomy and ER−/− crosses, still resulted in a high incidence of tumors in the lung and pituitary. We therefore conclude that AIB1 can exert its oncogenicity through tissue-specific estrogen-dependent and estrogen-independent functions.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent form of cancer in women in the United States. The prognosis and response to therapy largely depends on tumor phenotype. Targeted therapies are available for estrogen receptor α (ERα) positive tumors and for those tumors harboring HER2 amplifications. However tumors lacking hormone receptor expression or HER2 amplification, so-called triple-negative breast cancers, lack defined targeted therapies and have a poor prognosis. Furthermore, both de novo and acquired resistance to both endocrine and HER2-targeted therapies remain a significant problem and once patients develop metastatic disease cures remain extremely rare.

We have previously developed a mouse model for breast cancer by overexpressing the human gene AIB1 in the mammary gland of FVB mice (1) in order to investigate mechanisms of breast cancer development, metastasis formation, and drug resistance. AIB1 was discovered as a gene frequently amplified or overexpressed in breast cancer (2). It belongs to the p160 family of hormone receptor coactivators and consequently, one of its most studied functions is as an ERα coactivator (3). The AIB1-tg mice in our model developed invasive mammary gland tumors with a 75% incidence, as well as frequent tumors in other organs including the uterus, pituitary, lung, and skin. In addition, some of the mice harboring mammary gland tumors develop metastasis in bone and brain. These results demonstrated for the first time the ability of AIB1 to function as an oncogene.

The development of mammary and uterine tumors in AIB1-tg mice was consistent with its role as an estrogen receptor coactivator. However, the formation of tumors in the lung, skin, and pituitary was surprising, as these tissues are not known to be estrogen-dependent. Moreover, about 20% of the mammary tumors in AIB1-tg mice lacked expression of ERα. These observations raised the question whether AIB1 exerted its role as an oncogene through ERα coactivation alone or whether it had other functions as well.

In the present study we employed two strategies to address the role of estrogen and ERα in AIB1-mediated tumor formation. First, we surgically removed the ovaries of prepubertal AIB1-tg mice, in order to block gonadal estrogen production, which is the main source of estrogen in female mice. Ovariectomized (ovx) AIB1-tg mice did not develop any invasive mammary gland tumors. In sharp contrast, the incidence of pituitary, lung, skin, and bone tumors was higher than in non-ovariectomized AIB1 transgenic mice, indicating that only a subset of tumors was affected by the abolishment of gonadal estrogen production. Second, we crossed AIB1-tg mice with ERα null mutant mice. Lacking ERα, these mice are unable to respond to estrogen through this receptor, whether the estrogen is produced in the ovaries or in other tissues via aromatization of adrenal androgens. Again, these mice showed no signs of mammary tumors but developed tumors in lung, skin, and pituitary with the same high incidence as their AIB1-tg counterparts expressing ERα.

Our results indicate that AIB1 can cause tumor formation by estrogen-dependent and estrogen-independent mechanisms, depending on the organ or tissue affected. These results further suggest that AIB1 exerts oncogenic activities in cell signaling and/or gene regulation that are independent of its function as an estrogen receptor coactivator.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains and treatments

Animal experiments were compliant with the guidelines of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The AIB1-tg mouse line (FVB-MMTV-AIB1) has been previously described (1). FVB wild type (wt) mice were purchased from Charles River Labs. Ovaries from wt and AIB1-tg mice were surgically removed before onset of puberty. Mammary gland development was assessed after ovariectomy by whole mount analysis and H&E staining of cross sections (see below). Ovx animals were also aged and monitored for tumor formation. Mice were sacrificed when tumors developed or at 16 months of age, depending on tumor status and overall health conditions. Complete necropsies were then performed. DNA, RNA, and protein were extracted from various tissues for further analysis.

Heterozygous ERα deletion mutant mice (+/−) of the C57BL/6 strain were kindly provided by Dr. Chambon (4). These mice were crossed with the AIB1-tg mouse line FVB-MMTV-AIB1 to obtain the double mutant mouse line AIB1-tg × ERα +/− and then inbred to obtain the homozygous null mutant strain AIB1-tg × ERα−/−. Mammary gland development and tumor formation were assessed as described above.

Mammary gland whole mounts and immunostaining

Mammary glands were dissected, mounted on glass slides and stained as described in http://mammary.nih.gov/tools/histological/Histology/index.html. Tissues were fixed overnight in 10% neutralized buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin by standard procedures. Sections of 4µm thickness were stained with H&E or processed for immunohistochemistry analysis following antigen retrieval, using polyclonal ERα [Santa Cruz, diluted 1:3000] or monoclonal anti AIB1 antibody [BD Biosciences, diluted 1:200] and Hematoxylin counterstaining.

RNA isolation and qPCR

RNA isolation from tissue or tumors was done according to protocol provided by Trizol manufacturer (Invitrogen). 5 µg of RNA were reverse transcribed, using the ABI high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). The resulting cDNAs were used for quantitative PCR analysis using an Applied Biosystem 7300 RT PCR device and ABI SYBR Green master mix. The following primers were used: AIB1-sense 5’-GCGGCGAGTTTCCGATTTA-3’, antisense 5’-GCTCCCGTCTCCGTTTTTCT-3’ Actin-sense 5’-GTGGATCACCAAGCAGGAGT-3’, antisense 5’- TCGTCCTGAGGAGAGAGAGC-3’ Aromatase-sense 5’-AGGCCAAATAGCGCAAGATG-3’, antisense 5’-CGGGACCATGATGGTGACA-3’, ERα-sense 5’-TGCCTGGCTGGAGATTCTG-3’, antisense 5’-GCTTCCCCGGGTGTTCC-3’.

Protein extraction and Western blots analysis

Western blot analysis protocol has been previously described (5). Monoclonal anti-AIB1 antibody (BD Biosciences) and polyclonal anti-aromatase (Novus) were used for western blots. Polyclonal anti-calnexin (Stressgen) or β-actin antibodies (Sigma) were used as control for protein loading.

Tumor cell injection

Tumor cell lines were produced and maintained as previously described (5). Immortalized SCP2 cells were used as controls (6). One thousand tumor cells or 1 million control cells suspended in PBS (100ul) were injected in the thoracic fat pad of gland no. 3. For each experiment 5 intact female mice, 5 ovariectomized female mice and 5 male mice were used. The experiment was repeated three times. After injection, animals were routinely evaluated, tumor growth was monitored daily, and tumor size was measured using a caliper. Animals were sacrificed when tumor size reached 2 cm3 or the animal showed signs of discomfort or the skin was compromised. Complete necropsies were performed in all animals and tumor weight and tumor volume was assessed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for PCR and tumor injection studies were performed using unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t tests. Statistical significance was considered to be present at levels greater than 95% (p < 0.05). Means and standard deviations have been estimated for continuous variables. Tumor-free survival was calculated using the product-limit method of Kaplan-Meier (7). Comparisons between subgroups of study mice and the significance of differences between survivals rates were ascertained using a two-sided log-rank test (8). Differences between the two populations were considered significant at confidence levels greater than 95% (P<0.05). All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 5.0b for Mac OS X, GraphPad Software, San Diego California, USA.

Results

Tumors formed in AIB1 transgenic mice lack a correlation between AIB1 and estrogen receptor expression levels

We have previously reported that AIB1-tg mice display a high incidence of mammary tumors. While many of these mammary tumors are ERα(+), a significant proportion of them do not express detectable levels of ERα (1). This finding was somewhat surprising as ERα coactivation is thought to be the primary function of AIB1. This finding raised the question of whether AIB1-induced formation of ERα(−) mammary tumors is ER-independent. Alternatively, formation of ERα(−) tumors does initially require AIB1 coactivation of ER, but the tumors later become ER-independent and lose ER expression. Before we determined whether ERα and estrogen were necessary for AIB1-mediated tumorigenesis we evaluated the correlation between AIB1 and ERα expression in mammary gland tumors derived from AIB1-tg mice. We compared AIB1 and ERα mRNA and protein levels in a large number of tumor samples, using qPCR (Fig. 1A), and western blot (Supplemental Figure 1). Notably, several tumors with high AIB1 expression levels had undetectable or only barely detectable levels of ERα. A statistical analysis of the expression levels revealed the lack of a correlation between AIB1 and ERα mRNA levels (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Lack of correlation of ER and AIB1 expression in mammary tumor samples from AIB1 transgenic mice. A. Relative mRNA expression levels of AIB1 and ER were determined by qPCR in the tumor samples indicated. B. For each tumor sample the relative expression levels of AIB1 and ERα were plotted against each other. Linear regression analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0b for Mac OS X.

Ovariectomy impairs mammary gland development in AIB1-tg mice

In order to address the causal relationship between ER function, AIB1 expression, and mammary tumor formation, we abolished ovarian estrogen production in 25 AIB1-tg FVB mice and in 25 wild type (wt) FVB mice by performing ovariectomy before onset of puberty. First, we analyzed mammary gland development in these mice and compared it to untreated AIB1-tg and wt mice. Whole mount analysis of 20-week-old ovariectomized (ovx) mice revealed severe impairment of mammary gland development, consistent with previous reports showing the requirement of estrogen for normal mammary gland development (9–11). While mammary glands of AIB1 and wt mice with intact ovaries showed complete ductal elongation that fully branches out and penetrates the mammary fat pad (Fig. 2A), duct formation after ovariectomy was only rudimentary and ductal elongation and side branching were limited or absent in both AIB1-tg and wt mice (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Effect of ovariectomy on mammary gland development in AIB1tg mice. Wild type and AIB1-tg mice were ovariectomized at 3 weeks of age. At 20 weeks controls and ovx mice were sacrificed and mammary gland whole mounts were prepared. A. Upper panels: (left) untreated wt, (right) untreated AIB1. Lower panels (left) ovx wt, (right) Ovx AIB1 mouse (20× magnification). Arrow indicates example of branching that is absent in ovx wt mice. B. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of mammary glands (100×). Ovariectomy results in impaired mammary gland development in wt and AIB1-tg mice. AIB1-tg mice display hyperplasia and disorganized mammary duct architecture, even after ovariectomy. Inset: Detail of a hyperplastic mammary duct. (Right) example of a ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) observed in some of the ovx AIB1-tg mice. C. Effect of ovariectomy on ERα expression. Mammary gland cross-sections of untreated and ovx wt and AIB1-tg mice were probed with ERα antibody. All mice showed comparable ERα staining. D. ERα expression of DCIS.

We did however observe a difference in overall mammary gland development between AIB1-tg and wt mice after ovariectomy. While there was no detectable ductal branching in wt mice following ovariectomy, mammary glands of AIB1-tg mice showed limited, but clearly present ductal elongation and branching (Fig. 2A arrow). These results confirm that ovarian estrogen production is required for full ductal development. AIB1 overexpression alone cannot compensate for the lack of gonadal estrogen during mammary gland development, although it increases ductal elongation and branching to some extent. Serum estrogen levels were undetectable in the ovx mice that developed uterine atrophy and increased body weight (not shown), in agreement with previous studies (9, 12–14).

Despite impaired mammary gland development ovx AIB1 transgenic mice display mammary gland hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ

We have previously reported that AIB1 transgenic mice develop mammary epithelial hyperplasia, as evidenced by increased cell numbers and a disorganized pattern of cells surrounding the ducts (1). We now find that despite ovariectomy, the mammary glands of AIB1-tg mice also show an increase in cell number and disorganized structures as compared to wt mice (Fig. 2B). Thus, despite impaired mammary gland development, ovx AIB1-tg mice develop hyperplasia, and in some cases develop ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Fig. 2B right panel). These results indicate that the apparent proliferative effects of the AIB1 gene on mammary gland epithelial cells are exerted even in the absence of gonadal estrogen.

To determine the impact of estrogen removal on ERα expression levels, we performed immunohistochemistry. The pattern of ERα expression in luminal epithelial cells was not significantly different with or without ovariectomy, notwithstanding the smaller number of ducts and branches (Fig. 2C), indicating that estrogen deficiency does not influence ER expression levels or distribution. The DCIS lesions were also ERα(+) (Fig. 2D).

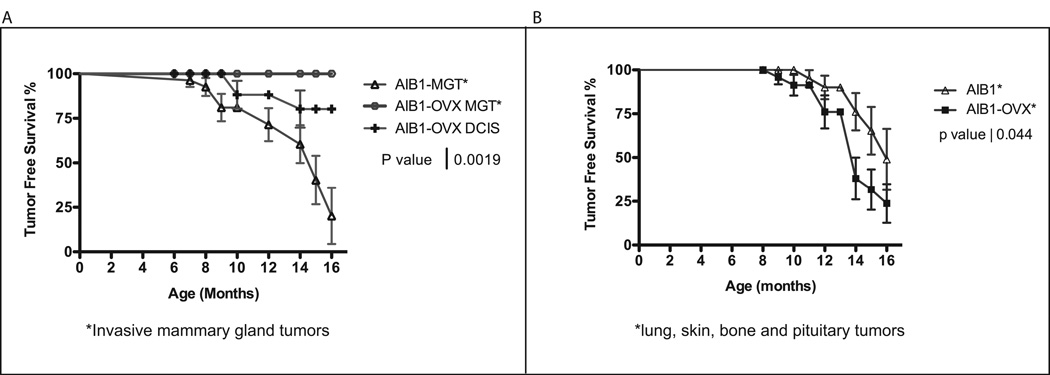

Ovariectomized AIB1-tg mice display a reduced incidence of tumors in hormone-dependent tissues, but an increased incidence of tumors in hormone-independent tissues

Twenty-five AIB1 transgenic mice treated by ovariectomy and 27 control AIB1 transgenic mice were aged and monitored for tumor formation. When animals presented evidence of disease or at the latest at the end of the study they were sacrificed and a full pathological examination was conducted. Data are presented as Kaplan Meier disease-free survival curves. Three categories of diseases were scored: invasive mammary gland tumors, non-invasive DCIS (both shown in Fig. 3A), and non-mammary gland tumors, such as lung, skin, bone, or pituitary tumors (Fig. 3B). DCIS does not lead to visible disease and consequently only was diagnosed when the animals suffered from other symptoms or at the end point of the study at 16 month. Most strikingly, none of the 25 ovariectomized AIB1 mice developed invasive mammary gland tumors (Fig. 3A) or uterine tumors (not shown). Thus, the incidence of invasive tumors in these hormone-dependent tissues is significantly reduced as compared to non-ovariectomized AIB1 mice. In sharp contrast, 13 out of 25 (52%) ovariectomized AIB1 mice developed tumors in hormone independent tissues, including lung, skin, pituitary, and bone. The incident of these tumors was even significantly higher than in untreated AIB1 mice, where 6 out of 27 (22%) of mice developed such tumors (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrate that AIB1 overexpression can give rise to two distinct groups of tumors, those that are prevented by ovariectomy and thus are estrogen-dependent (Fig. 3A) and those that remain unaffected or even increase in frequency upon ovariectomy and thus are independent of gonadal estrogen production (Fig. 3B). Representative sections of tumors developing in ovariectomized AIB1 transgenic mice are shown in supplementary Fig. S2. They include bone sarcoma, skin papilloma, lung carcinoma, and pituitary adenoma.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of tumor incidence in AIB1 transgenic mice with and without treatment by ovariectomy. A. Kaplan-Meier disease free survival curves comparing AIB1-tg mice that developed invasive mammary gland tumors with ovx AIB1-tg mice that only develop DCIS. B. Comparison of the incidence of non-mammary gland tumors in AIB1-tg mice vs. ovx AIB1-tg mice. Tumors developed in lung, skin, pituitary and skin.

Lack of ovarian production of estrogen leads to increased aromatase expression in the mammary gland

An essential step of estrogen biosynthesis is catalyzed by the enzyme aromatase. Aromatase is responsible for estrogen produced in the ovaries, but also for extragonadal estrogen production, for example in adipose tissue and skin (15–17). It has been suggested that aromatase expression is increased upon reduction of estrogen levels in an attempt by the organism to increase estrogen production to compensate for reduced estrogen signaling (18, 19). To determine whether abolishment of gonadal estrogen production leads to increased aromatase production in our system, we analyzed aromatase mRNA expression levels by qPCR in whole mammary glands from mature ovx and non-ovx AIB1-tg and wt mice. Ovariectomy led to a 3 to 4-fold increase in aromatase levels in both AIB1-tg and wt mice, (Supplemental Figure 3). Interestingly, AIB1-tg mice had about 2 to 3-fold lower aromatase expression as compared to wt mice. This difference was apparent in treated and untreated AIB1 mice, indicating that there might also be a negative feedback loop by which increased ER activity (due to increased AIB1 coactivation) down-regulates estrogen production by aromatase.

AIB1 × ERα−/− double mutant mice show impaired mammary gland development and no mammary tumors, but a high incidence of non-mammary tumors

We next investigated whether extragonadal estrogen was responsible for mediating the phenotype of AIB1 mice after ovariectomy by abolishing all estrogen signaling through removal of ERα. We did this by generating crosses of AIB1 transgenic mice with ERα null mutant mice. This approach should allow us to unequivocally dissect ERα-dependent and ERα-independent functions of AIB1-mediated tumorigenesis. Double mutant mice of the AIB1-tg × ERα−/− genotype were aged and monitored for tumor formation. When tumors were detected or at the end point of the study mice were sacrificed and dissected for pathological evaluation. As expected, all 16 of the double mutant mice displayed impaired mammary gland development. Specifically, mammary glands did not show signs of ductal elongation or side branching (Fig. 4), nor did they develop terminal end buds (not shown). A similar mammary gland phenotype was detected in control ERα−/− mice, in agreement with previous reports showing that ERα−/− mice only develop a truncated ductal rudiment, demonstrating that normal mammary gland development requires ERα signaling (20–24). As expected, no mammary or uterine tumors were found during 16 months of aging. However, 7 out of the 16 mice displayed lung or pituitary tumors, a comparable incidence to the 12 out of 25 AIB1-tg mice showing the same kinds of tumors after ovariectomy. The lung and pituitary tumors were of similar type and showed similar onsets than the tumors developing in the single mutant AIB1-tg mice (not shown). These results demonstrate that lung and pituitary tumors are indeed arising in an ERα and estrogen-independent manner.

Fig. 4.

Whole mounts depicting the effect of ERα removal. Left panel: 10 week old wt mouse, middle panel: 10 week old double mutant ERα−/− AIB1 mouse and right panel: 10 week old ERα−/− mutant mouse.

Lack of estrogen dependence of tumor growth in normal mice after injection with an ERα(+) AIB1 tumor cell line

Thus far we have shown that the formation of mammary tumors in AIB1-tg mice is strictly estrogen dependent. However, that does not necessarily mean that once mammary tumors have formed they continue to depend on estrogen. In fact, when we derived ERα(+) cell lines from AIB1-tg mammary tumors and injected those cell lines into normal mice, they only showed a limited response to tamoxifen, as we previously reported (5). Upon injection into normal, syngeneic mice, these mammary tumor cell lines have been shown to be particularly aggressive leading to uniform tumor formation in 100% of injected animals within 2 weeks (5).

We wanted to determine whether tumor growth upon injection of these ERα(+) AIB1 tumor cell line still required the presence of gonadal estrogen. Therefore, groups of 5 female wt-FVB mice were ovariectomized before onset of puberty. At 20-weeks of age mice were injected with one thousand cells of the ER(+) AIB1-tg tumor cell line. As control, 5 age-matched, intact female wt mice were injected, and 5 wt FVB male mice were treated with the same tumor cell line than the females. After injection, the volume of developing tumors was determined at regular intervals. Mice were sacrificed after 24 days or when tumor volumes reached 2 cm3. Tumors developed in 100% of the animals injected, regardless of gender or prior treatment with ovariectomy. The group of mice injected with the tumor cell line showed no difference in the tumor growth rate (Fig. 5A). No tumors were obtained when we injected the non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cell line SCP2 (6) into ovariectomized or untreated female mice or into male mice (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that an ER (+) tumor cell line derived from an AIB1 induced mammary tumor can form subsequent tumors, in vivo, in the absence of circulating, gonadal estrogen.

Fig. 5.

A. Estrogen-dependence of in vivo tumor growth potential of a mammary tumor cell line derived from AIB1 transgenic mice. Groups of wild type ovariectomized and control female mice and of wild type male mice were injected with the tumor cell line J110, derived from a mammary tumor of an AIB1 transgenic mouse. The cell line SCP2 was injected as a control. Tumor growth was monitored by palpation and caliper measurements. Final tumor size and metastasis formation were determined by pathological exam. There was no significant difference in tumor growth between all groups of mice injected with AIB1 tumor cells. B. Incidence of metastasis formation. The incidence of metastasis formation in the above mice was compared. Male mice and female mice after ovariectomy showed a significant increase in metastasis formation as compared to non-ovariectomized female mice.

In addition to tumor formation and growth we also assessed metastasis formation by dissection and full pathological analysis, as we have previously shown that this cell line can give rise to metastasis in various organs (5). As expected from those studies, we did observe a considerable number of metastasis in the injected animals. Surprisingly, however, ovx mice showed a dramatically larger proportion of metastasis (80–90% vs. 20–30% for non-ovariectomized mice, (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the rate of metastasis in male mice was also increased over female untreated mice (40–50% vs. 20–30%), suggesting that estrogen signaling may play a role in the prevention of metastasis.

Discussion

We have examined the dependency of AIB1-mediated tumor formation on estrogen in a mouse model in order to differentiate AIB1’s function as an estrogen receptor coactivator from other reported functions (25). We followed a dual strategy: in one set of experiments we removed the capacity for gonadal estrogen production, by performing ovariectomies. In a second set of experiments we removed the capacity for ERα signaling by creating AIB1-tg × ERα −/− double mutant mice. A comparison of the results from these two approaches allowed us to distinguish effects of gonadal estrogen and ERα on normal and premalignant mammary gland phenotype, mammary tumorigenesis, and tumor formation in other hormone-dependent and hormone-independent tissues.

Consistent with previous reports (9–11) (20–22) ovariectomy as well as deletion of the ERα gene both resulted in severely impaired mammary gland development. However, wt and AIB1-tg mice revealed different degrees of impairment after ovariectomy, as mammary glands of AIB1-tg mice showed limited, but clearly present ductal elongation and branching. These features were absent in AIB1 × ERα −/− mice, indicating that they are strictly dependent on ERα signaling. Unexpectedly, despite a general impairment of mammary gland development ovariectomy did not prevent the formation of AIB1-mediated mammary gland abnormalities including disorganized mammary gland architecture, the development of epithelial cell hyperplasia and the formation of ductal carcinoma in situ, indicative of a premalignant phenotype (26, 27). This observation raised the question whether these abnormalities were caused by AIB1 through an ERα dependent mechanism. We were able to the requirement for ERα by creating AIB1 × ERα−/− mice and examining their phenotype. As these mice did not show any evidence of the above AIB1-mediated mammary gland abnormalities we conclude that these features are strictly estrogen receptor-dependent. Thus, the premalignant mammary phenotype still present after ovariectomy must be the result of extragonadal estrogen production, ligand-independent activation of ERα, or both. We expect extragonadal estrogen levels to be somewhat increased after ovariectomy, due to the increase levels of aromatase mRNA and protein, which is consistent with previous reports of increased aromatase levels after ovariectomy in mice or rats (18, 19). However, we conclude that the levels of extragonadal estrogen were neither sufficient for normal mammary gland development nor for the generation of AIB1-induced mammary tumors.

Our findings establish that the development of mammary gland tumors and uterine tumors in the AIB1 model is strictly dependent on the production of gonadal estrogen, as ovx mice showed a 0% incidence of these tumors, as compared to a 75% incidence of mammary tumors (and 20% incidence of uterine tumors) for untreated AIB1-tg mice. These findings argue that AIB1 exerts it oncogenicity in the mammary gland and uterus by acting as a coactivator for estrogen-bound ERα leading to the expression of genes involved in proliferation and survival. Unexpectedly, we found that ovariectomy not only suppressed ER(+) but also ER(−) mammary gland tumors, which developed in untreated AIB1-tg mice with a ~ 15% incidence. This finding suggests that the formation of ER(−) tumors in AIB1 transgenic mice requires estrogen at some stage during tumorigenesis, but that this requirement is lost at a later stage of tumor progression.

This hypothesis is further supported by the results from an ER(+) mammary tumor cell line derived from an AIB1 mammary tumor that seems to represent an intermediate step on the path to estrogen independence. As shown in Figure 5A, injection of this tumor cell line can give rise to solid tumors in ovx female mice or in male mice. Thus, this particular tumor cell line is no longer dependent on gonadal estrogen for proliferation and survival, in vivo. It remains possible that this cell line uses extragonadal sources of estrogen or possibly produces estrogen in an autocrine manner. However, we consider this possibility unlikely, as the cell line has also ceased to respond to estrogen, in vitro, and is not affected by treatment with ER antagonist ICI 182780 (data not shown). Therefore, this cell line seems indeed to be estrogen-independent despite continued expression of ER (also see Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Models of estrogen-dependent and estrogen-independent AIB1 actions. A. Role of estrogen and ERα in mammary gland development. B. Estrogen dependence of tumor progression and metastasis formation.

A totally unexpected finding from these injection experiments was that estrogen seems to have a protective effect from the development of metastasis, since ovariectomized mice have a significantly increased rate of metastasis following injection of the ER(+) tumor cell line. The increase in metastasis formation after ovariectomy seems indeed to be due to reduced estrogen levels rather than to the effect of a prior surgery, since male mice (not treated by any surgery) showed a similar increase in metastasis over female untreated mice. Thus, while this cell line does not seem to require ER signaling for proliferation and survival, ER must still provide some other signals that result in the protection from metastasis, most likely by regulating transcription of genes involved in migration or homing (see in Fig. 6B). These findings indicate that loss of ER may present additional, thus far unanticipated risks in the progression of breast cancer.

In sharp contrast to mammary tumors and uterine tumors, which were completely abolished by ovariectomy or deletion of the ERα gene, tumors in other organs, such as lung, pituitary, and skin, still persisted following these treatments. This indicates that AIB1 does not function as an estrogen receptor coactivator in the formation of these latter tumors and thus, must have functions other than ER coactivation that can result in oncogenesis. AIB1 has been reported to serve as a coactivator for several other transcription factors, besides the estrogen receptor, including other hormone receptors such as progesterone receptor (PR), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and retinoic acid receptor (RAR), when overexpressed in the presence of ligand (28–30). AIB1 has also been shown to function in a hormone receptor-independent fashion to co-activate other p300/CBP associated transcription factors, such as STAT and AP-1 (31). Furthermore, we and others have implicated AIB1 in the regulation of several signaling pathways, including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and the NF-κB pathway (1, 32). At this point we don’t know whether any of these functions, an entirely new function, or a combination of these is responsible for tumorigenesis in lung, pituitary, and skin mediated by AIB1.

It is interesting to note that in the absence of estrogen or ER the incidence of non-mammary gland tumors increases rather than remaining unchanged (see figure 3B). This indicates that there may be a connection between the estrogen-dependent and -independent functions of AIB1. For example, various pathways or molecules (including ER) might compete for AIB1, such that AIB1 might be the limiting factor in deciding which pathway is being activated. This result thus highlights a tight regulation of the various functions of AIB1.

Our findings that AIB1 can mediate its oncogenicity in the lung in an estrogen-independent manner have some immediate medical relevance, as AIB1 overexpression and amplification have recently been shown to correlate with poor prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer in humans (33). However, such correlation studies cannot address cause and effect and therefore it remains unclear whether in humans AIB1 overexpression is causal to lung cancer formation and whether AIB1 functions as an ERα coactivator in the lung. The data from our mouse model clearly demonstrate that AIB1 overexpression by itself is sufficient to cause lung cancer and to do so in an estrogen-independent manner. Our findings may thus have important implications in the search of drugs and drug targets for lung cancer. Taken together, our present study demonstrates that AIB1 can exert its oncogenicity through at least two distinct, tissue-dependent mechanisms, one that is estrogen receptor-dependent and one that is estrogen receptor-independent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Pierre Chambon for providing the ER −/− mice and Dr. Stefan Doerre for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants P01 CA8011105 and P50C89393, the DF/HCC Breast Cancer Spore grant. M. I. Torres-Arzayus received research funding from BIRCWH K12 (HD051959, supported by NIMH, NIAID, NICHD, and OD).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Torres-Arzayus MI, Font de Mora J, Yuan J, et al. High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, et al. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277(5328):965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Gomes PJ, Chen JD. RAC3, a steroid/nuclear receptor-associated coactivator that is related to SRC-1 and TIF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(16):8479–8484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupont S, Krust A, Gansmuller A, Dierich A, Chambon P, Mark M. Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development. 2000;127(19):4277–4291. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Arzayus MI, Yuan J, DellaGatta JL, Lane H, Kung AL, Brown M. Targeting the AIB1 oncogene through mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in the mammary gland. Cancer Res. 2006;66(23):11381–11388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desprez PY, Hara E, Bissell MJ, Campisi J. Suppression of mammary epithelial cell differentiation by the helix-loop-helix protein Id-1. Mol and Cell Bio. 1995;15(6):3398–3404. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan E, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation for incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures (with discussion) J R Stat Soc A. 1972;135:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westerlind KC, Gibson KJ, Malone P, Evans GL, Turner RT. Differential effects of estrogen metabolites on bone and reproductive tissues of ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(6):1023–1031. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.6.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel CW, Silberstein GB, Strickland P. Direct action of 17 beta-estradiol on mouse mammary ducts analyzed by sustained release implants and steroid autoradiography. Cancer Res. 1987;47(22):6052–6057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silberstein GB, Van Horn K, Shyamala G, Daniel CW. Essential role of endogenous estrogen in directly stimulating mammary growth demonstrated by implants containing pure antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1994;134(1):84–90. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan DL, Kurita T, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR, Cooke PS. Role of stromal and epithelial estrogen receptors in vaginal epithelial proliferation, stratification, and cornification. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4345–4352. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotinun S, Westerlind KC, Kennedy AM, Turner RT. Comparative effects of long-term continuous release of 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone and 17 beta-estradiol on bone, uterus, and serum cholesterol in ovariectomized adult rats. Bone. 2003;33(1):124–131. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurita T, Lee KJ, Cooke PS, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR. Paracrine regulation of epithelial progesterone receptor by estradiol in the mouse female reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 2000;62(4):821–830. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/62.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grodin JM, Siiteri PK, MacDonald PC. Source of estrogen production in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36(2):207–214. doi: 10.1210/jcem-36-2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson ER, Clyne C, Rubin G, et al. Aromatase--a brief overview. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:93–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081601.142703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulun SE, Chen D, Lu M, et al. Aromatase excess in cancers of breast, endometrium and ovary. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;106(1–5):81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao H, Tian Z, Cheng L, Chen B. Electroacupuncture enhances extragonadal aromatization in ovariectomized rats. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thordarson G, Lee AV, McCarty M, et al. Growth and characterization of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary tumors in intact and ovariectomized rats. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(12):2039–2047. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocchinfuso WP, Korach KS. Mammary gland development and tumorigenesis in estrogen receptor knockout mice. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2(4):323–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1026339111278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunha GR, Young P, Hom YK, Cooke PS, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB. Elucidation of a role for stromal steroid hormone receptors in mammary gland growth and development using tissue recombinants. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2(4):393–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1026303630843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallepell S, Krust A, Chambon P, Brisken C. Paracrine signaling through the epithelial estrogen receptor alpha is required for proliferation and morphogenesis in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2196–2201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510974103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mueller SO, Clark JA, Myers PH, Korach KS. Mammary gland development in adult mice requires epithelial and stromal estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2002;143(6):2357–2365. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bocchinfuso WP, Lindzey JK, Hewitt SC, et al. Induction of mammary gland development in estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141(8):2982–2994. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao L, Kuang SQ, Yuan Y, Gonzalez SM, O'Malley BW, Xu J. Molecular structure and biological function of the cancer-amplified nuclear receptor coactivator SRC-3/AIB1. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83(1–5):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardiff RD, Moghanaki D, Jensen RA. Genetically engineered mouse models of mammary intraepithelial neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5(4):421–437. doi: 10.1023/a:1009534129331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardiff RD, Anver MR, Gusterson BA, et al. The mammary pathology of genetically engineered mice: the consensus report and recommendations from the Annapolis meeting. Oncogene. 2000;19(8):968–988. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14(2):121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20(3):321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown K, Chen Y, Underhill TM, Mymryk JS, Torchia J. The coactivator p/CIP/SRC-3 facilitates retinoic acid receptor signaling via recruitment of GCN5. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(41):39402–39412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torchia J, Rose DW, Inostroza J, et al. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature. 1997;387(6634):677–684. doi: 10.1038/42652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu RC, Qin J, Hashimoto Y, et al. Regulation of SRC-3 (pCIP/ACTR/AIB-1/RAC-3/TRAM-1) Coactivator activity by I kappa B kinase. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(10):3549–3561. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3549-3561.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He LRZH, Li BK, Zhang LJ, Liu MZ, Kung HF, Guan XY, Bian XW, Zeng YX, Xie D. Overexpression of AIB1 negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jan 11; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp592. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.