Abstract

It is generally agreed that the successful treatment of a badly broken tooth with pulpal disease depends not only on good endodontic therapy, but also on good prosthetic reconstruction of the tooth after the endodontic therapy is complete. Often, we come across an endodontically treated tooth with little or no clinical crown in routine clinical cases. In such cases, additional retention and support of the restoration are difficult to achieve. Two case reports are discussed here where structurally compromised, endodontically treated, posterior teeth were restored using the Richmond crown in the first case, and by the use of two nonparallel cast posts in the second case.

Keywords: Cast post, post endodontic restorations, Richmond crown

INTRODUCTION

The goal of endodontics and restorative dentistry is to retain the natural teeth with maximal function and pleasing aesthetics.[1] It is generally agreed that the successful treatment of a badly broken tooth with pulpal disease depends not only on good endodontic therapy, but also on good prosthetic reconstruction of the tooth after the endodontic therapy is complete. [2] The primary purpose of a post is to retain a core in a tooth that has lost its coronal structure extensively.[3,4]

During the treatment procedure, a structurally compromised tooth can give rise to complications such as root fracture, loss of restorative seal, dislodgement of core, and periodontal injury due to biological width invasion during margin preparation. [1] There are many techniques of restoring a badly broken molar tooth after successful endodontic treatment, which should be complemented by a sound coronal restoration. This should ideally meet the requirements of function and aesthetics. It is easier to make cast metal restorations with the aid of posts for retention and lasting service. However, whenever possible, the metal can be camouflaged by veneering with tooth-colored restorations.

In this article, two cases have been elaborated where two different techniques have been employed for the final restoration.

CASE REPORTS

Case I

A 23 year-old patient reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, D.A.P.M.R.V Dental College, Bangalore, for a routine check-up. On examination, it was found that tooth 36 had undergone root canal treatment 8-10 months ago. However, tooth 36 was asymptomatic and the clinical crown was <2 mm. The radiographic examination of tooth 36 revealed straight root canals with well condensed guttapercha filling extending 0.5 mm short of the radiographic apex. No periapical changes were noted in relation to tooth 36. An occlusal model evaluation was done to assess the amount of space available for the post endodontic restoration to restore the tooth to function.

The following points were reviewed before proceeding further.

The pulp chamber preparation included removal of any endodontic filling material and blocking out the undercuts with type IX Glass Ionomer cement. The root canal preparation included the post length[5-9] in the posterior tooth, which was dictated by the remaining bone support, root anatomy, root curvatures, and the apex obturation. Care was taken to ensure that the length of the post was 2/3 the length of the canal or in other words, ½ the bone supported the length of the root. The more coronally located the root curve, the shorter the post should be.[10] Thus, 1 mm of the surrounding dentin was preserved to maintain the strength of the root.[1]

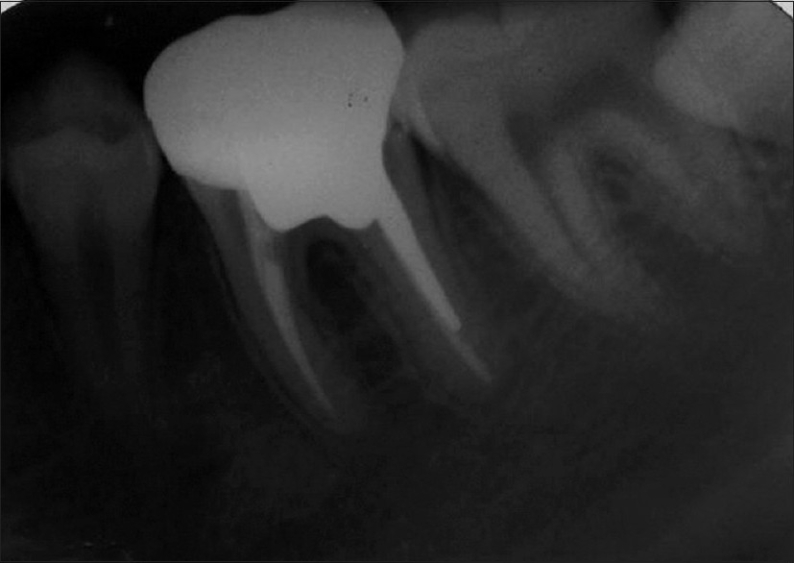

A crown-lengthening procedure was carried out using the tissue recontouring system to expose 2 mm of the tooth structure and to have the crown ferrule effect for better retention. A GG drill was used to remove the guttapercha. Post space was prepared in the distal canal of tooth 36 with Peeso reamer. An H-file was used circumferentially to smoothen the preparation of the post space [Figure 1]. A slot or cloverleaf was prepared near the orifice region with a tapered carbide bur. Also, tooth preparation was carried out for the full metal crown.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing the slot preparation

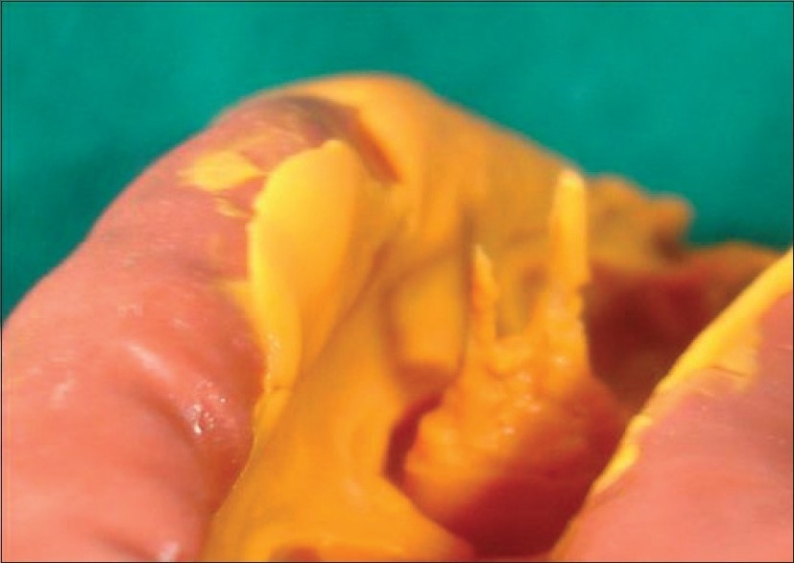

Orangewood stick (post) was selected and trimmed and shaped conically to fit passively to full length into the prepared post space in the distal canal. The orangewood stick was coated with adhesive and kept aside. Light-body, rubber-based, impression material was injected into the prepared post space in the distal canal and the orangewood stick was placed in the post space. Additional material was then injected around the preparation and the tray loaded with the heavy-body, rubber-based material was placed on the light-body material. The impression of the post space was picked up along with the tooth preparation for the full crown [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Impression of the post space and full crown preparation was taken in rubber base impression material

The impression was poured in die material to obtain a master cast. Adjoining teeth (the distal surface of the second premolar and the mesial surface of the second molar) in the model were scraped to provide additional room for the wax to ensure tight contact of the restoration. A wax pattern was made on the master cast and the casting procedure was carried out.

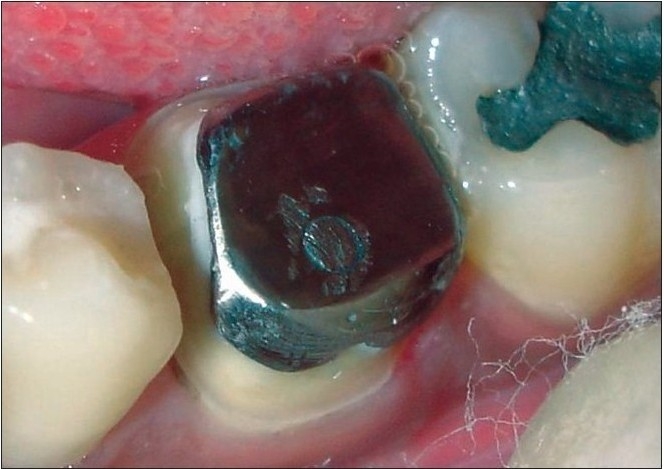

The final casting comprised of directly attaching the post to the crown [Figure 3] which was cemented using type I Glass Ionomer luting agent; the occlusion was then checked [Figure 4]. The case was followed for 16 months in which no root fracture, no loosening or dislodgement of the post, and no secondary caries were reported.

Figure 3.

Final casting comprised of post directly attached to crown (Richmond crown)

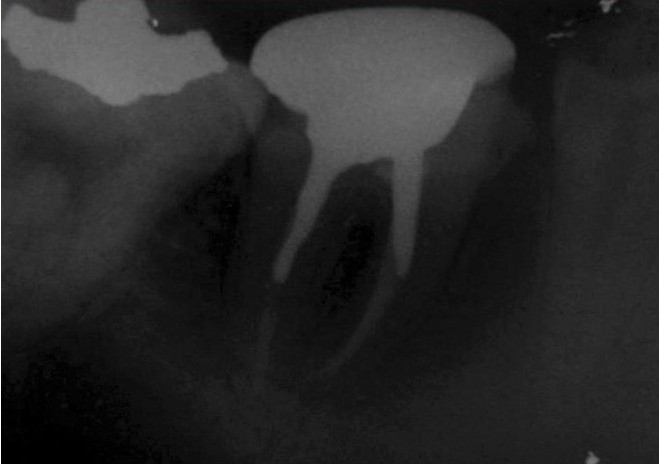

Figure 4.

Post cementation: Radiograph

Case 2

A patient aged 26 years reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, D.A.P.M.R.V Dental College, Bangalore, with the chief complaint of dull pain in the lower left back tooth region since 12–15 days. Vitality test with an electric pulp tester showed a delayed response suggestive of partial necrosis in tooth 36. The radiographic examination revealed radiolucency suggestive of caries involving the pulp of tooth 36 and periodontal ligament widening. A diagnosis of chronic apical periodontitis was made and root canal treatment was performed; the clinical crown was equal to 2 mm. An occlusal model evaluation was done to assess the amount of space available for the post endodontic restoration to restore the tooth to function.

In this case, two nonparallel cast posts were used to restore the tooth. The case was reviewed for the points discussed under case 1.

A GG drill was used to remove the guttapercha. Post space was prepared in the distal and mesiobuccal canals of tooth 36 with Peeso reamer. An H-file was used circumferentially to smoothen the preparation of the post space [Figure 5] A slot or cloverleaf preparation was prepared near the orifice region with a tapered carbide bur. Also, tooth preparation was carried out for the full metal crown.

Figure 5.

After removal of guttapercha from the distal and mesiobuccal canals along with preparation for full metal crown

Orangewood stick (post) was selected and trimmed and shaped conically to fit passively to full length into the prepared post space in the distal and mesiobuccal canals. The orangewood stick was coated with adhesive and kept aside. Light-body, rubber-based impression material was injected into the prepared post space in the distal and mesiobuccal canals and the orangewood stick was then placed into the prepared post spaces. Additional material was then injected around the preparation. The tray loaded with the heavy-body material was placed on the light-body material and an impression was picked up of the post space along with the tooth preparation for the full crown [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Rubber base impression of the post space along with the full crown preparation was taken

The impression was poured into die material to obtain a master cast on which the wax pattern was made. The wax pattern had one post attached to the core and another separate, withdrawable post [Figure 7]. The casting procedure was carried out and the final casting comprised of one post attached to the core and another separate, withdrawable post [Figure 8]. Both the withdrawable post and the post attached to the core were cemented using type I Glass Ionomer luting agent [Figure 9].

Figure 7a.

Wax pattern was made on the master cast with one post attached to the core and other withdrawable post

Figure 8.

The final casting comprised of one post attached to the core and the other separate withdrawable post

Figure 9a.

Cementation of the post attached to the core and the separate withdrawable post

Figure 7b.

Wax pattern showing withdrawable post

A second impression was made for restoring the tooth with a full metal crown and poured into die material to obtain the master cast. A wax

Figure 9b.

Postcementation radiograph

pattern was made for the full metal crown and the casting procedure was carried out. The tooth was restored with a full metal crown and the occlusion was checked. The case was followed for 14 months in which no root fracture, no loosening or dislodgement of post, and no secondary caries were reported.

DISCUSSION

The number of endodontic procedures has increased steadily in the past decade with highly predictable results. Therefore, restoration of teeth after endodontic treatment is becoming an integral part of restorative practice in dentistry. Proper restoration of endodontically treated teeth requires a sound knowledge of the endodontic, periodontal, restorative, and occlusal principles.[11] Post space preparation requires good understanding and knowledge of tooth anatomy to avoid unnecessary mishaps.[12]

Endodontically treated molar teeth should receive cuspal coverage, but in most cases, they do not require a post. When a post is required as a result of extensive loss of the natural tooth substance, as in the cases discussed above, it should be placed in the largest and straightest canal to avoid weakening the root, during post space preparation and root perforation in curved canals.[2,13] As the distal root canal of the mandibular molar was the largest and straightest in case 1, it was used for post placement. In case 2, the distal and mesiobuccal canals were prepared to receive the two nonparallel cast posts to provide additional retention. But, rarely are two posts required in posterior teeth in routine cases.

When a considerable amount of tooth structure has been lost, as in the cases discussed above, because of caries or previous restoration or the endodontic treatment itself, special techniques are needed to restore such a tooth. This loss of tooth structure makes retention of a subsequent restoration problematic and increases the likelihood of fracture during function. In these cases, crown lengthening can be done either surgically or by orthodontic extrusion to get the ferrule effect. In case 1, crown lengthening was carried out using the tissue recontouring system (electro surgery) as it offers the advantage of leaving a virtually bloodless site for immediate procedure.

In the cases discussed in this article, special attention was given towards straight line access and the path of withdrawal of the post for preparing the tooth to receive the post. Also, the undercuts in the pulp chamber were blocked using type I Glass Ionomer Cement for the easy removal of the impression. A slot or cloverleaf was prepared near the orifice region which aids in the seating of the casting and also resists torque.

For the cases discussed in this article, a Ni-Cr alloy was used for casting the posts as high-strength alloys are needed to restore the posterior teeth which carry the major masticatory forces. But their hardness might be a major disadvantage in adjustment and may predispose the tooth to root fracture. Other substitutes which can be used for the cases discussed above include the cast gold alloy which provides high strength and is easy to adjust. One six-year retrospective study reported a success rate of 90.6% using a cast post and core as a foundation restoration. [2]

The teeth with minimal vertical tooth structure remaining for crown margins are subjected to flexion forces under function. As less cervical tooth structure is available, cervical stiffening from a more rigid post is needed to protect the crown margins and resist leakage. At the same time, force dissipation from a more resilient post is needed to resist root fracture. [10] Therefore, cast metal post systems were chosen in the cases discussed in this article. The advantages reported with the cast post system include i) custom fitting to the root configuration, ii) adaptability to large, irregularly shaped canals and orifices, iii) strength, and iv) the availability of considerable documentation to support their effectiveness.[10]

Although there are certain disadvantages of the cast post and core placement procedure-their high cost, lower retention, difficult temporization between appointments, risk of casting inaccuracies, additional removal of tooth structure,[10] and greater number of visits needed to complete the treatment and laboratory fabrication.[2]

The clinician must judge every situation on its individual merits and select a procedure that fulfills the needs of the case while maximizing retention and minimizing stress. Although any number of post designs may be used in a clinical situation, success is dictated by the remaining tooth structure available after endodontic therapy.

This article presents the methods to salvage and restore badly broken molars and restore them to function by the different techniques discussed herein.

Acknowledgment

Dr. S. Jagadish, Professor and HOD, Dr. Shashikala. K, Professor, Dr. Keshava Prasad B. S., Professor, Dr. Suman Makam, Asst. Professor.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenstiel SF, Land MF, Fujimoto J. 2nd ed. Contemporary fixed prosthodontics; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin S. Weine endodontic therapy. (6 th ed) :553–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett SO. Construction of detached core crowns for pulpless teeth in only two sittings. J Am Dent Assoc. 1968;77:843–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1968.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung W. Properties of and important concepts in restoring the endodontically treated teeth. Dent Asia. 2004:40–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingle JI, Bakeland LK. Endodontics. (5th ed) :913–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane JJ, Burgess JO. Modification of the resistance form of amalgam coronal-radicular restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:470–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90281-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins JW. Guidelines for the restoration of endodontically treated teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:558–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1990.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen H. Operative procedures on mutilated endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1961;11:973–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung W. A review of the management of Endodontically treated teeth Post, core and the final restoration. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:611–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Hargreaves KM. Pathways of the pulp. (9 th ed) :786–821. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverstein WH. The reinforcement of weakened pulpless teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1964;14:372–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern N, Hirschfeld Z. Principles of preparing endodontic treated teeth for dowel and core restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;30:162–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(73)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodacre CJ, Spolnik KJ. The prosthodontic management of endodontically treated teeth: A literature review: Part I: Success and failure data, treatment concepts. J Prosthodont. 1994;3:243–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1994.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]