Abstract

Fruit-set in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) depends on gibberellins and auxins (GAs). Here, we show, using the cv MicroTom, that application of N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA; an inhibitor of auxin transport) to unpollinated ovaries induced parthenocarpic fruit-set, associated with an increase of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) content, and that this effect was negated by paclobutrazol (an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis). NPA-induced ovaries contained higher content of GA1 (an active GA) and transcripts of GA biosynthetic genes (SlCPS, SlGA20ox1, and -2). Interestingly, application of NPA to pollinated ovaries prevented their growth, potentially due to supraoptimal IAA accumulation. Plant decapitation and inhibition of auxin transport by NPA from the apical shoot also induced parthenocarpic fruit growth of unpollinated ovaries. Application of IAA to the severed stump negated the plant decapitation effect, indicating that the apical shoot prevents unpollinated ovary growth through IAA transport. Parthenocarpic fruit growth induced by plant decapitation was associated with high levels of GA1 and was counteracted by paclobutrazol treatment. Plant decapitation also produced changes in transcript levels of genes encoding enzymes of GA biosynthesis (SlCPS and SlGA20ox1) in the ovary, quite similar to those found in NPA-induced fruits. All these results suggest that auxin can have opposing effects on fruit-set, either inducing (when accumulated in the ovary) or repressing (when transported from the apical shoot) that process, and that GAs act as mediators in both cases. The effect of NPA application and decapitation on fruit-set induction was also observed in MicroTom lines bearing introgressed DWARF and SELF-PRUNING wild-type alleles.

Fruit-set is the transition from the static condition of the ovary in the full developed flower to the active metabolic condition following pollination and fertilization (Leopold and Scott, 1952). Plant hormone quantification and application of plant growth substances to unpollinated and pollinated ovaries in diverse species have led to the conclusion that fruit-set depends on hormones synthesized in the developing seeds and/or ovary following pollination and fertilization (Abad and Monteiro, 1989; Gillaspy et al., 1993; García-Martínez and Hedden, 1997). Gibberellins and auxins (GAs) are considered the main compounds involved in that process.

In tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), application of diverse GAs and inhibitors of GA biosynthesis (Fos et al., 2000, 2001; Gorguet et al., 2005; Serrani et al., 2007b) and determination of GA levels (Bohner et al., 1988; Koshioka et al., 1994; Fos et al., 2000) have shown that fruit-set depends on GAs. The involvement of the SlDELLA repressor in this process has also been demonstrated (Martí et al., 2007). In pollinated ovaries, GA content increases as a result of higher GA 20-oxidase (GA20ox) metabolic activity associated with an increase of GA20ox transcripts (Martí et al., 2007; Olimpieri et al., 2007; Serrani et al., 2007b; for a scheme of the GA metabolic pathway, see Supplemental Fig. S1). In addition to GAs, auxin application (Abad and Monteiro, 1989; Koshioka et al., 1994; Alabadí et al., 1996; Ramin, 2003; Serrani et al., 2007a) and ectopic expression of genes encoding enzymes of auxin biosynthesis (Pandolfini et al., 2002) can also induce fruit-set in tomato. Early growth of tomato fruit has been associated with an increase of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA; Varga and Bruinsma, 1976) and IAA-like substances (Mapelli et al., 1978). More recently, the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 (ARF8) from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Goetz et al., 2006) and tomato (Goetz et al., 2007), ARF7 from tomato (de Jong et al., 2009b), and the Aux/IAA protein IAA9 from tomato (Wang et al., 2005) have been characterized as transcription factors from the auxin signaling pathway that repress fruit-set in the absence of fertilization. All these results support the idea that auxins are also involved in tomato fruit-set (Pandolfini et al., 2007; de Jong et al., 2009a).

Application of auxin transport inhibitors to unpollinated ovaries induces parthenocarpic fruit-set in cucumber (Cucumis sativus; Beyer and Quebedeaux, 1974) associated with auxin accumulation in the ovary (Kim et al., 1992). In the case of pollinated tomato, ovaries treated with 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA; an inhibitor of auxin transport) had reduced seed and fruit size and blossom-end rot occurrence was higher, although the fruits contained higher levels of IAA than untreated fruits (Hamamoto et al., 1998). This effect has also been found in parthenocarpic tomatoes induced with diverse auxin transport inhibitors (Banuelos et al., 1987).

It is known that there is competition between vegetative and reproductive growth (Tamas, 1995). For instance, pea (Pisum sativum) fruit development reduces apical shoot growth, and this effect is proportional to the number of growing fruits (García-Martínez and Beltrán, 1992), while reduction of vegetative growth by application of plant growth retardants (Davis and Curry, 1991) or mechanical elimination of apical and axillary shoots in grape (Vitis vinifera; Coombe, 1962) and apple (Malus domestica; Quinlan and Preston, 1971) favors fruit growth. In the case of pea, plant decapitation not only increases growth of pollinated ovaries but also induces parthenocarpic growth of unpollinated ovaries (Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1980). The inductive effect of plant decapitation on parthenocarpic growth in pea is negated by IAA applied to the stump (Rodrigo and García-Martínez, 1998). The mutant gio of pea has enhanced IAA transport from the apical shoot and significantly reduced response of unpollinated ovaries to applied GA3 (Rodrigo et al., 1998). It has also been found that diffusible IAA is involved in the correlative signal regulating dominance relationships between fruits, and also between fruits and shoots, in apple and tomato (Gruber and Bangerth, 1990). All these results suggest that the repressive effect of the apical shoot on fruit-set is mediated by auxin.

In this work, we have investigated the roles of auxins transported from the ovary and from the apical shoot in fruit-set and growth in tomato using the cv MicroTom (MT). This cultivar has been reported and used as a convenient model system to investigate diverse aspects of developmental regulation (Meissner et al., 1997; Serrani et al., 2007a; Wang et al., 2009; Campos et al., 2010). However, the presence of several mutations (mainly dwarf [d] and self-pruning [sp], affecting brassinosteroid biosynthesis and responsible for its determinate phenotype, respectively) has suggested that some caution is required when obtaining data using this cultivar (Martí et al., 2006). For this reason, in addition to MT, we have also used plants bearing introgressed D and Sp wild-type alleles (MT-D and MT-SP lines) to validate the most relevant data. Application of N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA; an auxin transport inhibitor) causes IAA to accumulate in both unpollinated and pollinated ovaries, showing that there is basal auxin biosynthesis in the ovary even in the absence of pollination and fertilization. Interestingly, NPA was able to induce parthenocarpic growth of unpollinated ovaries but prevented the growth of pollinated ovaries. Plant decapitation and NPA application to the apical shoot also induced parthenocarpic growth. This effect is mediated by auxin through a change of GA metabolism in unpollinated ovaries due mainly to increases of CPS (for copalyl diphosphate synthase) and GA20ox transcript levels.

RESULTS

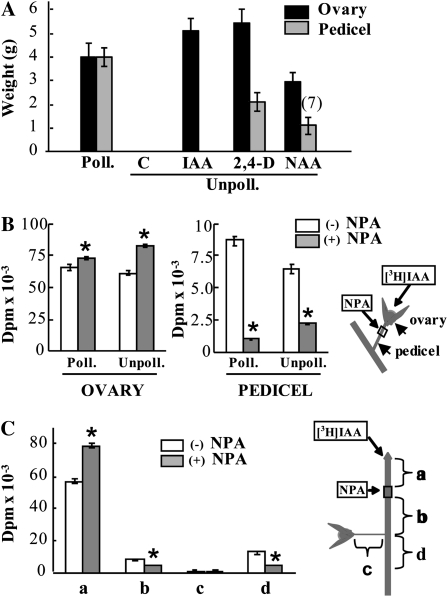

Auxin from the Ovary and the Apical Shoot Is Transported Basipetally

To investigate whether auxin is transported basipetally from the ovary, we first applied auxin directly to the unpollinated ovary or to the pedicel and examined parthenocarpic fruit-set and growth. As expected from previous results of our laboratory (Serrani et al., 2007a), application of three different auxins (IAA, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4-D], and α-naphthaleneacetic acid [NAA]) to unpollinated ovaries induced 100% parthenocarpic fruit growth. However, when the natural auxin IAA was applied to the pedicel, no fruit-set was obtained (Fig. 1A). In the case of the synthetic auxins 2,4-D and NAA, the size of fruits induced by pedicel application was significantly smaller compared with ovary application, and fruit-set of NAA-induced fruits was also less than 100% (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that auxin is not (in the case of IAA) or is poorly (in the cases of 2,4-D and NAA) transported to the ovary. To assay auxin transport directly, we applied [3H]IAA to unpollinated and pollinated ovaries without or with NPA (an inhibitor of auxin transport) to the pedicel in lanolin, and 2 d later the amount of 3H was determined in the ovary and the pedicel. In both kinds of ovaries, NPA treatment increased significantly the amount of 3H remaining in the ovary while reducing the amount transported basipetally to the pedicel (Fig. 1B). When [3H]IAA was applied to the pedicel, no radioactivity could be detected in the ovary (data not shown). In a parallel experiment, we found by HPLC that at least 36% of radioactivity in the pedicel was recovered as a compound with the same retention time as [3H]IAA (Supplemental Fig. S2C). Metabolism of part of the applied [3H]IAA may have occurred either during or after transport in the target tissues.

Figure 1.

Auxin transport in the ovary and apical shoot. A, Comparative effects of IAA, 2,4-D, and NAA application directly to unpollinated ovary versus pedicel on fruit-set and growth. Hormone application was carried out at day 0 to the ovary (in 10 μL of solution at concentrations of 200 ng μL−1 IAA, 20 ng μL−1 2,4-D, and 200 ng μL−1 NAA) or to the pedicel (in about 20 mg of lanolin at concentrations 10 times higher than to the ovary), and fruits were collected at day 20. Pollinated (Poll.) and unpollinated (Unpoll.) control (C) ovaries were treated with the same volume of solvent solution to the ovary or amount of lanolin to the pedicel. Weight values are means of developed fruits ± se (n = 12). The value in parentheses indicates the number of fruits developed from the 12 ovaries treated; absence of that notation means 100% fruit set. B, Inhibition of basipetal [3H]IAA transport applied to unpollinated and pollinated ovaries (1,670 Bq per ovary) by NPA applied in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1) to the pedicel. The applications were made at day 0, and the material (ovaries and pedicels) was collected 48 h later. Data are means ± se (n = 3, 15 ovaries and pedicels per replicate). Asterisks denote significant differences (P < 0.05, Student's t test) between untreated and treated tissues. C, Inhibition of basipetal [3H]IAA transport applied to the vegetative apex (1,670 Bp per plant) by NPA in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1) applied below the vegetative apex. The applications were made at day 0, and the material was collected 48 h later. Data are means ± se (n = 3, six plants per replicate). Asterisks denote significant differences (P < 0.05) between untreated and treated tissues.

Auxin transport from the apical shoot was also analyzed by applying [3H]IAA to the apex, in the absence and presence of NPA applied immediately below the apex in lanolin, and determining the amount of 3H in lower stem sections (b and d in Fig. 1C) and ovary pedicel (c in Fig. 1C). Radioactivity was found in the stem sections, and its amount was significantly reduced by NPA (Fig. 1C). In this case, about 42% of recovered radioactivity was [3H]IAA, according to HPLC retention time (Supplemental Fig. S2E). In contrast, essentially no 3H was found in the ovary pedicel (or in the ovary; data not shown) without or with NPA (Fig. 1C), supporting the hypothesis that IAA from the apex was also transported basipetally through the stem but that it was unable to enter into the pedicel and ovary.

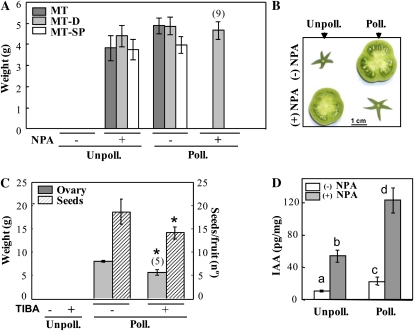

Inhibition of Auxin Transport from the Ovary Induces Fruit Growth of Unpollinated Ovaries But Negates That of Pollinated Ovaries

Unpollinated ovaries of MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants did not set, while application of NPA to the pedicel of those ovaries at the time equivalent to anthesis induced 100% parthenocarpic fruit-set (Fig. 2A). The size of the three kinds of parthenocarpic fruits was similar to that of pollinated fruits (Fig. 2A). In contrast, NPA application to the pedicel of pollinated ovaries completely blocked fruit-set in MT and MT-SP plants and was reduced to almost 50% in MT-D plants (Fig. 2A). The lower effect of NPA in decreasing fruit-set of pollinated MT-D ovaries may be due to the more vigorous growth of MT-D compared with MT and MT-SP plants (Supplemental Fig. S3), which may reduce the efficiency of the dose of NPA used in the experiment. The opposite effect of NPA application on unpollinated and pollinated ovaries can be well visualized in Figure 2B for MT. Application of TIBA (another auxin transport inhibitor) to the pedicel did not enhance fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries, although fruit-set of pollinated ovaries was reduced associated with a slight decrease in the number of seeds per fruit (from 19 ± 2 to 14 ± 2; Fig. 2C). IAA concentration in pollinated ovaries was double that in unpollinated ovaries (about 20 pg mg−1 versus 10 pg mg−1, respectively; Fig. 2D). As expected, NPA application enhanced IAA levels equally in both kinds of ovaries (five to six times), although the absolute concentration in pollinated ovaries (120 pg mg−1 fresh weight) was about 2.5-fold higher than in unpollinated ovaries (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Effects of auxin transport inhibition on fruit-set and growth. A, Effects of NPA on fruit-set and growth of unpollinated (Unpoll.) and pollinated (Poll.) ovaries from MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants. Data are means ± se (n = 16). B, Images of representative unpollinated and pollinated MT ovaries nontreated and treated with NPA. Mean weight of unpollinated/−NPA and pollinated/+NPA MT ovaries were 12 and 30 mg, respectively. C, Effects of TIBA on fruit-set and growth and number of seeds in unpollinated and pollinated MT ovaries. Data are means ± se (n = 8). Asterisks denote significant differences (P < 0.05) between untreated and treated organs. D, IAA concentration (ng g−1) in unpollinated and pollinated MT ovaries nontreated and treated with NPA. IAA values are means ± se (n = 3, 15 ovaries/fruits per replicate). Different letters on the bars represent means that are statistically different (P < 0.05). NPA and TIBA were applied in lanolin to the pedicel (at 1.5 and 15 mg g−1, respectively) at day 0, and fruits were collected 20 d (A–C) or 10 d (D) later. For meaning of values in parentheses, see legend of Figure 1A. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Application of NPA simultaneously with IAA and GA3 enhanced final fruit growth induced by those hormones (Fig. 3). This effect was probably due to the accumulation of IAA in the ovary produced by NPA, leading to an additional effect over that induced by the exogenous hormones. Since induced accumulation of endogenous IAA by NPA had an added effect on applied IAA, this also suggests that the relatively high dose of exogenous IAA (2,000 ng) was not saturated, probably because of degradation or transport difficulty. In contrast, a dose effect of 2,4-D on the response to NPA was observed (Fig. 3): additional at 2 ng, none at 20 ng, and negative at 200 and 2,000 ng of 2,4-D, in the last two cases probably due to an overdose (Fig. 3). The amount of 2,000 ng of 2,4-D clearly had a toxic effect by itself (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of NPA on growth of parthenocarpic fruits induced by IAA, 2,4-D, and GA3. NPA was applied to the pedicel in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1), and IAA (2,000 ng), 2,4-D (2, 20, 200, and 2,000 ng), and GA3 (2,000 ng) in 10 μL of solution, to unpollinated ovaries at day 0, and material was collected at day 20. Data are means of developed fruits ± se (n = 12). For meaning of values in parentheses, see legend of Figure 1A. Asterisks denote significant differences (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01) between untreated and treated tissues.

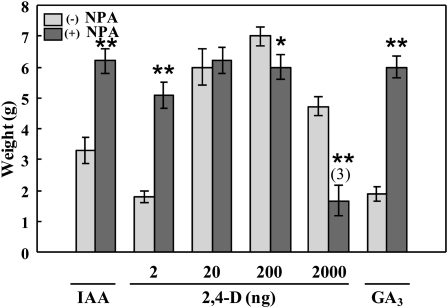

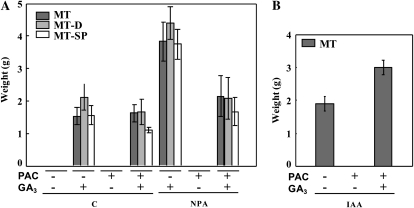

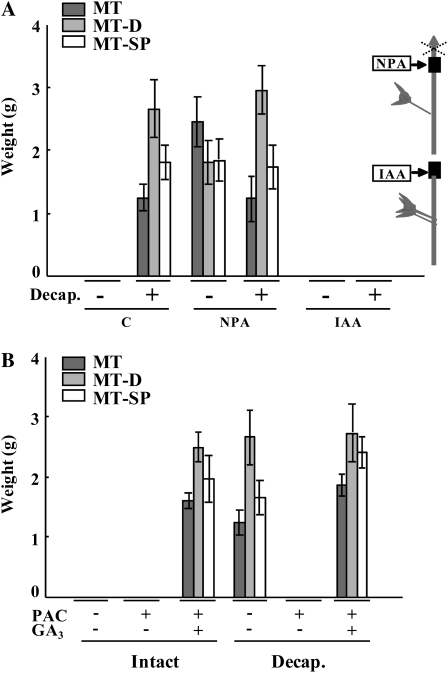

Induction of Fruit-Set and Growth by NPA Applied to the Pedicel Is Mediated by GAs

The effect of NPA on fruit-set and growth of unpollinated ovaries from MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants was abolished by watering the plants with paclobutrazol (PAC; an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis). The effect of PAC on fruit-set was fully reversed, and that on fruit size was partially reversed, by exogenous GA3 application to the ovary (Fig. 4A). We also found that PAC completely negated tomato fruit-set induced by the natural auxin IAA applied to the ovary of MT plants and that GA3 reversed this effect (Fig. 4B). This kind of PAC treatment had no effect on vegetative growth of the plant (data not shown), suggesting that fruit-set induced by IAA accumulated in the ovary following NPA application was mediated by GAs. To assess this hypothesis, we quantified GAs from the early-13-hydroxylation pathway (the most relevant in tomato fruit; Fos et al., 2000) in 10-d-old NPA-treated ovaries from MT plants (Table I). The levels of GA1 (the active GA; 3.0 ng g−1) and of its GA44, GA19, and GA20 precursors (particularly of GA20) and metabolite (GA8) were much higher than those of unpollinated nontreated ovaries of the same age (Table I).

Figure 4.

PAC inhibition and reversion by GA3 of parthenocarpic fruit-set and growth of unpollinated MT, MT-D, and MT-SP ovaries induced by NPA applied to the pedicel (A) and of MT unpollinated ovaries induced by IAA applied to the ovary (B). C, Control. NPA was applied in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1), and IAA (2 μg) and GA3 (2 μg) in 10 μL of solution, to the ovary at day 0. PAC was applied to the roots in 10−5 m solution. Data are means ± se (n = 16).

Table I. GA concentration (ng g−1 fresh weight) in unpollinated control ovaries, ovaries treated with NPA, and decapitated plants.

Flowers were emasculated on day −2, and application of NPA and plant decapitation were carried out on the day equivalent to anthesis (day 0). Ovaries and fruits were collected at day 10 (control and NPA-treated plants) or day 13 (decapitated plants). Values are means ± se of three biological replicates.

| Ovaries | Weight | GA53 | GA44 | GA19 | GA20 | GA29 | GA1 | GA8 |

| mg fruit−1 | ||||||||

| Control | 2 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | <0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| NPA treated | 650 ± 12 | <0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 10.6 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.4 |

| Decapitated plants | 670 ± 11 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 26.1 ± 5.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 1.2 |

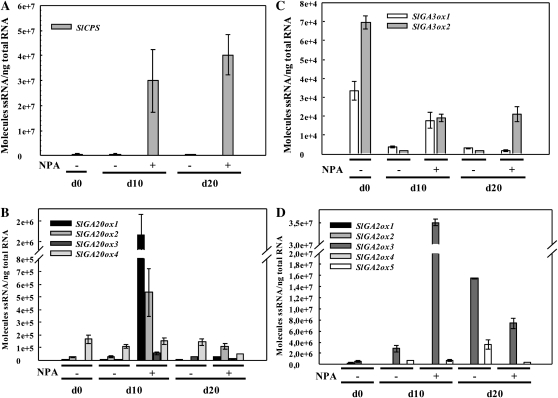

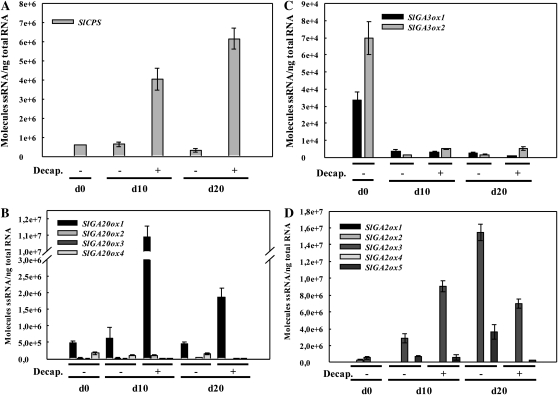

Fruit-set in tomato induced by pollination (Serrani et al., 2007b) or auxin application (Serrani et al., 2008) depends on their effect on GA metabolism. We determined whether NPA treatment of unpollinated ovaries also changed transcript levels of genes encoding enzymes of GA biosynthesis (SlCPS, SlGA20ox1, -2, -3, and -4, and SlGA3ox1 and -2) and catabolism (SlGA2ox1, -2, -3, -4, and -5) by quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis at day 0 (day equivalent to anthesis) and 10 and 20 d later. Transcript levels of SlCPS were higher in NPA-treated ovaries 10 and 20 d after treatment (Fig. 5A). SlGA20ox1 and -2 transcript contents were also clearly higher after 10 d of treatment. Transcript accumulation of SlGA3ox1 and -2 was relatively high at day 0 and decreased later, although that of SlGA3ox1 remained slightly higher in NPA-treated ovaries than in control ovaries at day 10 and those of SlGA3ox2 remained slightly higher at day 10 and day 20. Transcript content of all SlGA2ox genes was relatively low in day-0 ovaries, and that of SlGA2ox3 increased later on, being higher in NPA-treated ovaries than in control ovaries at day 10 but lower at day 20. These results support the hypothesis that the accumulation of IAA in unpollinated ovaries treated with NPA induces fruit-set and growth through the increase of GA biosynthesis.

Figure 5.

Effects of NPA application to the pedicel on transcript levels of genes of GA biosynthesis and inactivation in unpollinated ovaries. A, SlCPS. B, SlGA20ox1, -2, -3, and -4. C, GA3ox1 and -2. D, SlGA2ox1, -2, -3, -4, and -5. NPA was applied in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1) to the pedicel at day 0, and ovaries were collected 10 and 20 d later. −, Control; +, ovaries treated with NPA. The values are means of three biological replicates ± se.

Basipetal Transport of IAA from the Apical Shoot Inhibits Fruit-Set and Growth

Elimination of the apical shoot (plant decapitation) induced parthenocarpic fruit-set and growth of unpollinated ovaries in MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, application of NPA just below the intact apical shoot to prevent IAA transport also induced parthenocarpic growth (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the apical shoot inhibits ovary growth through basipetal auxin transport. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that the positive effect of decapitation on fruit-set induction was fully negated by the application of IAA to the severed shoot (Fig. 6A). It is important to note that, as shown before (Fig. 1C), [3H]IAA applied to the shoot was transported basipetally without entering into the ovary.

Figure 6.

Induction of parthenocarpic fruit-set and growth of unpollinated ovaries by plant decapitation. A, Effects of plant decapitation (Decap.) and application of NPA to the apical shoot of intact MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants, and reversion of the plant decapitation effect by IAA. Data are means ± se (n = 16 for MT and MT-D, n = 5 for MT-SP). C, Control. The inset is a scheme indicating the sites of NPA and IAA application. B, PAC inhibition of fruit-set induced by plant decapitation, and reversion by GA3 in MT, MT-D, and MT-SP plants. Data are means ± se (n = 16). NPA (1.5 mg g−1) and IAA (1 mg g−1) were applied to the apical shoot in lanolin (see inset in A), and GA3 (2,000 ng) was applied to the ovary in 10 μL of solution, at day 0, and materials was collected at day 20. PAC was applied as 10−5 m solution to the roots from day −7 every 2 d. Plant decapitation was done at day 0.

Induction of Fruit-Set by Plant Decapitation Is Mediated by GAs

To investigate the possibility that the effect of plant decapitation on fruit-set induction may be mediated by GAs, we watered decapitated plants with PAC and found that fruit-set was completely inhibited (Fig. 6B). Application of GA3 to unpollinated ovaries from decapitated and PAC-treated plants restored fruit-set and growth (Fig. 6B), suggesting that GAs play a role in plant decapitation-induced parthenocarpy. This hypothesis was also supported by results from GA quantification of parthenocarpic fruits that developed in MT decapitated plants. These fruits contained elevated concentrations of GA1 (5.7 ng g−1) and its precursors (GA53, GA44, GA19, and GA20) and GA8 metabolite (Table I) compared with unpollinated ovaries in intact plants, even higher than those developed upon NPA application described earlier (Table I).

Transcript levels of genes encoding enzymes of GA biosynthesis (SlCPS, SlGA20ox, and SlGA3ox) and GA catabolism (SlGA2ox) were determined in unpollinated ovaries from intact and decapitated plants at days 0, 10, and 20 post decapitation. Transcript contents of SlCPS and SlGA20ox1 were much higher in ovaries from decapitated plants than from intact plants (Fig. 7, A and B). SlGA3ox1 and -2 transcript levels decreased after day 0, and no apparent effect of decapitation was observed (Fig. 7C). In the case of SlGA2ox genes, the level of SlGA2ox3 transcript increased in decapitated ovaries at day 10 but was lower than those of intact plants at day 20. The level of SlGA2ox5 transcripts was lower in ovaries from decapitated plants, but only at day 20 (Fig. 7D). The increases of SlCPS and SlGA20ox1 transcripts were similar to those found in NPA-treated unpollinated ovaries; therefore, they are in agreement with the hypothesis that fruit-set induction by decapitation is mediated by GAs through induction of GA biosynthesis.

Figure 7.

Effects of plant decapitation on transcript levels of genes of GA biosynthesis and inactivation in unpollinated ovaries. A, SlCPS. B, SlGA20ox1, -2, -3, and -4. C, GA3ox1 and -2. D, SlGA2ox1, -2, -3, -4, and -5. Plant decapitation (Decap.) was carried out at day 0, and ovaries were collected 10 and 20 d later. −, Control; +, decapitated plants. The values are means of three biological replicates ± se.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that IAA is transported basipetally both from the ovary and from the apical shoot. This conclusion is based on the following evidence: (1) IAA induced fruit-set efficiently when applied directly to unpollinated ovary but not when applied to the pedicel; (2) no 3H was found in the ovary when [3H]IAA was applied to the pedicel; and (3) NPA (an auxin transport inhibitor) blocked transport of [3H]IAA from the ovary to the pedicel and from the apex to the stem. In all these cases, it was confirmed that about 40% of 3H recovered in the target tissues remained as [3H]IAA. This agrees with the poor transport into the ovary of IAA applied to the pedicel described previously (Homan, 1964) and with the basipetal polar transport of IAA found in the tomato fruit pedicel (Sastry and Muir, 1965). It is generally accepted that auxins are transported basipetally in different organs like roots, coleoptiles, and stem segments of diverse species and that this polar transport is the result of the basal cellular localization of auxin transporters (Morris et al., 2004). This is in contrast with the nonpolar transport of GAs demonstrated before by [3H]GA1 moving equally in the two directions of pea stems (Clor, 1967) and freely in the plant when applied to vegetative and reproductive tissues of pea (Peretó et al., 1988) and tomato (Couillerot, 1981).

Unpollinated and pollinated 10-d-old tomato ovaries contained IAA, although more in the latter than in the former (about twice as much; Fig. 2D). A maximum of auxin-like activity was found in pollinated tomato ovaries 10 d after anthesis (Mapelli et al., 1978). IAA in pollinated ovaries may come from the developing fertilized ovules (seeds), which are known to contain high levels of IAA (Varga and Bruinsma, 1976). However, unpollinated ovaries have not been reported previously to contain IAA, and our results suggest that they have basal IAA biosynthesis even in the absence of pollination/fertilization. It is not known whether this IAA is present in unfertilized ovules, pericarp tissues, or both. Application of NPA induced parthenocarpic fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries (Fig. 2, A and B) and accumulation of IAA both in unpollinated and pollinated ovaries (Fig. 2D), supporting the hypothesis that IAA biosynthesis is taking place in both kinds of ovaries, although in the case of unpollinated ovaries probably only at the basal rate compared with pollinated ones. Most interesting, since IAA level in unpollinated NPA-treated ovaries was about twice that of untreated pollinated ovaries, this suggests that NPA-induced parthenocarpy was the result of IAA accumulation. Moreover, pollinated ovaries treated with NPA had even higher IAA levels due to blockage of its transport out of the ovary and failed to set fruit. Together, these results suggest that an optimal IAA level is necessary to promote fruit growth. Induction of parthenocarpic growth by morphactin, an inhibitor of auxin transport, has been described in cucumber (Beyer and Quebedeaux, 1974). The application of TIBA, another inhibitor of auxin transport, to unpollinated tomato ovaries did not induce parthenocarpy. However, pollinated ovaries treated with TIBA displayed reduced fruit-set and growth and the developed fruits had lower numbers of seeds (Fig. 2C). A negative effect of TIBA on fruit growth and seed development was also observed by Hamamoto et al. (1998). The different effects of both kinds of auxin transport inhibitors were probably due to TIBA being less efficient than NPA in blocking IAA transport. Our results raise the importance of auxin homeostasis in the ovary for appropriate control of fruit-set and growth. This conclusion is further strengthened by the observation that additional accumulation of endogenous IAA as a result of IAA blockage transport by NPA may have a negative effect on 2,4-D fruit-set induction (Fig. 3).

Parthenocarpic growth induced by NPA applied to the pedicel or by IAA directly to the ovary was inhibited by PAC, an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis (Fig. 4). Moreover, NPA application induced elevated GA contents (of active GA1 and its precursors and metabolite) in MT ovaries (Table I). NPA application to unpollinated ovaries also increased transcript levels of SlCPS, SlGA20ox1 and -2, and SlGA3ox1 and -2 (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the enhancement of these transcript levels by NPA was quite similar to that found previously by application of 2,4-D to unpollinated ovaries (Serrani et al., 2008), strongly suggesting that parthenocarpic growth induced by IAA accumulation in NPA-treated ovaries is mediated by GAs through an increase of GA biosynthesis. It is of interest that, as occurs in pollinated ovaries (Serrani et al., 2007b), there is also an increase of SlCPS transcript content both after 2,4-D application (Serrani et al., 2008) and NPA treatment (Fig. 5A). However, since overexpression of AtCPS in Arabidopsis increased ent-kaurene but not active GA content (Fleet et al., 2003), we do not know the possible role of SlCPS increase in active GA homeostasis in relation to tomato fruit-set. An important difference between the results obtained by exogenous 2,4-D (Serrani et al., 2008) and NPA (this work) application was the absence of down-regulation of SlGA2ox2 expression in the last case. This may be due to different effects on gene expression between synthetic (2,4-D) and natural (IAA) auxin, or between the ways of increasing auxin content in the ovary (applied exogenously or by blocking IAA transport with NPA). Our conclusion on the mediation of GAs in auxin-induced fruit-set is also supported by the previous observation that parthenocarpic fruit growth in tomato by auxin application is also substantially reduced in the presence of GA biosynthesis inhibitors (Serrani et al., 2008). The increase of SlGA2ox3 transcript content found in NPA-induced ovaries (Fig. 5D) may be a consequence of the well-known positive feedback effect of GA on the expression of this kind of GA-inactivating enzymes (Yamaguchi, 2008).

Tomato plant decapitation induced parthenocarpic growth, and the effect of decapitation was reversed by IAA applied to the stump (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that the apical shoot inhibits tomato ovary growth through basipetal auxin transport. This phenomenon was similar to that described in pea, where decapitation also induces parthenocarpic growth (Carbonell and García-Martínez, 1980) and IAA application reverses that induction (Rodrigo and García-Martínez, 1998). This resembles the so-called apical dominance phenomenon, where basipetal IAA transport from the apex inhibits axillary bud growth (Tamas, 1995; Dun et al., 2006; Ongaro and Leyser, 2008). In both cases, IAA inhibition (of axillary bud and ovary growth) is carried out without the hormone entering the inhibited organ, so the auxin moving in the stem must act indirectly, and an unknown secondary signal(s) may be necessary to mediate the auxin effect. In contrast to apical dominance, where cytokinins and strigolactones have also been shown to be involved in shoot branching (Dun et al., 2006; Ongaro and Leyser, 2008), evidence on a secondary signal in the case of ovary growth inhibition by the apical shoot is scarce. In the case of pea, abscisic acid accumulates in unpollinated ovaries, and blockage of IAA transport from the apical shoot by TIBA prevents that accumulation, although it was not sufficient to trigger parthenocarpy (Rodrigo and García-Martínez, 1998). Based on results of transcriptome analysis, it has been proposed that abscisic acid and ethylene may have an antagonistic function to auxin and GAs to keep the tomato ovary in a dormant state before pollination and fertilization (Vriezen et al., 2007). Cytokinins have also been suggested as mediators between IAA from the apical shoot and fruit development (Rodrigo et al., 1998; Bangerth et al., 2000). In contrast to the second messenger theory, Bangerth (1989) proposed the “primigenic dominance” hypothesis, where the polar IAA export of the earlier developed sink (in our case, the shoot apex) inhibits the IAA export of later developed sinks (in our case, the unpollinated ovary); the depressed IAA export of the subordinated sink would act as the signal leading to inhibited ovary development, unless strong IAA biosynthesis and export occur as a result of pollination and ovule fertilization. A corollary of this hypothesis is that auxin needs to be transported out of the pollinated ovary for fruit-set. However, the observations that parthenocarpic fruit-set can be induced in unpollinated ovaries by blocking auxin transport with NPA (Fig. 2), and that the response to different hormones is enhanced by NPA (Fig. 3), do not support that hypothesis.

We have found that the inhibitory effect of tomato ovary growth by IAA transported from the apex seems to be mediated by preventing the synthesis of active GA. This conclusion is supported by the following evidence: (1) no parthenocarpic growth occurred in decapitated plants treated with PAC, but GA3 counteracted the effect of PAC (Fig. 6B); (2) the concentration of active GA1 and its precursors was much higher in ovaries from decapitated plants (where basipetal auxin transport from the apex did not occur) than in ovaries from intact plants (Table I); and (3) transcript levels of SlCPS and SlGA20ox1, genes encoding enzymes of GA biosynthesis, increased upon decapitation of the plant (Fig. 7). Therefore, we propose that the inhibitory effect of IAA transported basipetally from the apical shoot on fruit-set is carried out through inhibiting GA biosynthesis in the ovary. As a result, removal of the apical shoot should increase in the ovary the concentration of GAs, hormones responsible for fruit-set in tomato (Fos et al., 2000, 2001; Martí et al., 2007; Olimpieri et al., 2007; Serrani et al., 2007b, 2008). Auxins have been found to regulate GA metabolism in vegetative tissues of pea (O'Neill and Ross, 2002) and Arabidopsis (Frigerio et al., 2006) and in fruits of pea (Ngo et al., 2002; Ozga et al., 2003) and tomato (Serrani et al., 2008; this work). However, in contrast to these cases, where auxins applied or present in the target organs alter GA metabolism, leading to enhanced active GA concentration, we hypothesize that in our case the effect of auxin transported from the apex seems to prevent those GA metabolic changes without entering in the ovary through a still unknown secondary messenger, which would avoid the accumulation of active GA in this organ and thus fruit-set.

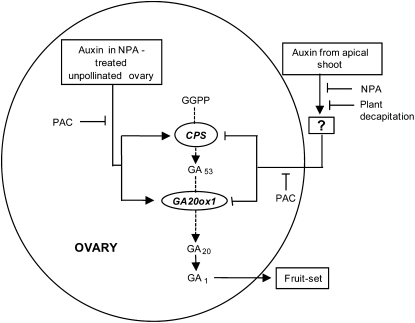

In summary, as shown in the scheme in Figure 8, our results show that IAA synthesized both in the ovary and in the apical shoot controls fruit-set in tomato. Since IAA synthesis occurs at a very low level in the ovary, the positive effect of IAA from the ovary on fruit-set was only observed upon blockage of its transport (which produced IAA accumulation in the ovary) using an auxin transport inhibitor (NPA). In the case of auxin from the apical shoot, its negative effect on fruit-set occurs without entering the ovary through a still unknown second messenger (? in Fig. 8) and was relieved by blocking its transport with NPA or by plant decapitation. Interestingly, in both cases, the effect of auxin on fruit-set and growth was correlated with changes of GA metabolism in the unpollinated ovary. Auxin accumulated in the ovary enhanced transcript levels of genes encoding GA biosynthetic enzymes (SlCPS, GA20ox1, and GA20ox2 to a lesser extent), thus inducing fruit-set. In contrast, auxin from the apical shoot seems to prevent the increase of transcript levels of genes encoding GA biosynthetic enzymes (SlCPS and SlGA20ox1), therefore avoiding fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries. The results presented in this article were obtained with MT, whose use has been described and should be taken with caution due to the presence of several mutations in that cultivar. However, the main results were also confirmed with MT lines carrying wild-type D and Sp genes. Therefore, it can also be concluded that at least the d and sp mutations (which reduce brassinosteroid content and induce a determinate phenotype, respectively) do not affect the conclusions raised in this work.

Figure 8.

Proposed model for auxin (from the ovary and from the apical shoot)-GA interaction on parthenocarpic fruit-set. Auxin accumulated in unpollinated ovary upon NPA application and auxin transported from the apical shoot (without entering in the ovary) regulate GA metabolism genes in the ovary in opposite ways, associated with induction (auxin in the ovary) and repression (auxin from the apical shoot) of fruit-set. For clarity, only GA20ox1, the main GA20ox gene regulated in both cases, is given in the scheme. GA20ox2, GA3ox1, and GA3ox2 transcript levels also increased in NPA-induced ovaries at day 10 after treatment but not in decapitated plants. The question mark (?) means that IAA from the apex does not need to enter the ovary for fruit-set inhibition and that this effect depends on unknown second messenger(s). GGPP, Geranylgeranyl diphosphate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Plants of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum ‘MicroTom’; Meissner et al., 1997) were used in the experiments. MT-D and MT-SP plants (BC6F2) carrying the D and Sp wild-type alleles, respectively, were also used (isolation of those lines was carried out using the protocol described by Zsögön et al. [2008]; see plant phenotypes in Supplemental Fig. S3). The plants (one per pot) were grown in 1-L pots with a mixture of peat:vermiculite (1:1) in a greenhouse under 24°C day/20°C night conditions and irrigated daily with Hoagland solution. Natural light was supplemented with Osram lamps (Powerstar HQI-BT, 400 W) to get a 16-h-light photoperiod. Only one flower per truss and the first two trusses were left per plant for the experiments, as described previously (Serrani et al., 2007a), unless otherwise stated. Flower emasculation was carried out 2 d before anthesis (day −2) to prevent self-pollination. All nonselected flowers were removed.

Plant decapitation was performed by severing about 1 cm of the apical shoot the day equivalent to anthesis of the flowers (day 0). Only two flowers per plant, from the first two bunches, emasculated the same day were used in this kind of experiment. All the axillary buds that developed as a result of plant decapitation were removed to prevent competition with developing fruits.

Application of Plant Growth Substances and Inhibitors

Application to unpollinated ovaries of the auxins IAA, 2,4-D, and NAA and of GA3 (all reagents from Duchefa) was carried out at the concentration specified for each experiment on the day equivalent to anthesis (day 0) in 10 μL of 5% ethanol and 0.1% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich) solution. IAA was also applied to the stump of severed apical shoots in lanolin (10 mg g−1 lanolin paste; prepared by mixing 2.75 g of lanolin, 450 μL of Tween 80, 100 μL of distilled water, and 33 mg of IAA). Application of IAA, 2,4-D, NAA, and GA3 was also carried out on pedicels of unpollinated flowers in lanolin paste (all at concentrations of 1 mg g−1; prepared as described before) on the day equivalent to anthesis. PAC (an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis; Duchefa) was applied to the roots in the nutrient solution at 10−5 m every 2 d, starting when flowers on which the effect of the inhibitor was going to be determined were about 7 d before anthesis (3–4 mm bud size) so it would be transported in time to the ovary. NPA and TIBA (inhibitors of auxin transport; Duchefa) were applied in solution to the ovaries (3 μg, in 10 μL) or in lanolin (1.5 mg g−1 lanolin) to ovary pedicels and to apical shoots. Control ovaries were treated with the same volume of solvent solution or amount of lanolin.

Determination of [3H]IAA Transport Applied to Ovaries and Apical Shoot

Tritium-labeled IAA ([5-3H]IAA; specific activity of 925 GBq mmol−1; Amersham Biosciences) was applied to unpollinated ovaries (less than 2 mg fresh weight, after removing petals and anthers from bud flowers just before anthesis) or to apical shoots (1,670 Bq per ovary or apical shoot) in 10 μL of a 10% methanol solution on day 0.

Ovaries, pedicels, and stem segments (as indicated in Fig. 1) were collected 48 h after application. For ovary treatment, 15 unpollinated ovaries (from flowers emasculated at day −2) and pedicels were collected together per replicate. In the case of shoot treatment, six plants per replicate were used. Three replicates were performed per treatment. All samples were then frozen in N2 and homogenized in 80% methanol. After overnight agitation at 4°C, the extracts were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm and the supernatant was collected to determine 3H concentration per ovary or per tissue section by radioactive scintillation counting using OptiPhase HiSafe 3 (Perkin-Elmer) as liquid scintillation cocktail. Extracts were also analyzed by HPLC (4-μm C18 column, 15 cm long, 3.9 mm i.d.; NovaPak; Millipore) using a 10% to 100% methanol gradient at 1 mL min−1 over 40 min.

Quantification of Endogenous IAA

Unpollinated and pollinated 10-d-old ovaries, untreated and treated with NPA applied to the pedicel, were collected for IAA extraction. Aliquots of 15 mg fresh weight were extracted with 0.5 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.05 m, pH 7.0) in the presence of [13C6]IAA (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; 500 pg per sample) as internal standard as described by Edlund et al. (1995). The extract, after adjusting the pH with 1 m HCl to 2.7, was passed through a preequilibrated C8 column (Isolute C8-EC; International Sorbent Technology). The column was washed with 2 mL of 10% methanol solution containing 1% acetic acid, eluted with 2 mL of 70% methanol and 1% acetic acid, and the eluate was evaporated to dryness. The residue, dissolved in 0.2 mL of 2-propanol, was methylated with trimethylsilyl-diazomethane in hexane (Aldrich), taken to dryness under vacuum, and trimethylsilylated in 15 μL of acetonitrile plus 15 μL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide + 1% trimethyl chlorosilane. For gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, the sample was dissolved in 20 mL of n-heptane and injected into a gas chromatograph (HP 6890 Series; Agilent Technologies) equipped with a 30-m × 0.25-mm i.d. analytical gas chromatography column with a 0.25 μm CP-Sil8 CB-MS stationary phase (Chrompack; Varian), using an autoinjector (HP 7683 Series; Agilent Technologies) coupled to a mass spectrometer (JMS-700 MStation double-focusing magnetic sector instrument; JEOL) using the conditions described by Ljung et al. (2005). The amount of endogenous IAA in the sample was quantified by isotopic dilution as described by Ljung et al. (2005). All samples were analyzed using three biological replicates.

Quantification of Endogenous GAs

GAs were determined in unpollinated ovaries from intact plants and in parthenocarpic fruits developed after NPA application and in decapitated plants. Aliquots of 4 to 6 g fresh weight were extracted with ethanol, purified by solvent partition and HPLC, and quantified by gas chromatography-selected ion monitoring according to the protocol described elsewhere (Fos et al., 2000; Serrani et al., 2007b), using [3H]GA20 and [3H]GA9 to monitor the separation of GAs after HPLC and [17,17-2H]GA1, [17,17-2H]GA8, [17,17-2H]GA19, [17,17-2H]GA20, [17,17-2H]GA29, [17,17-2H]GA44, and [17,17-2H]GA53 (purchased from Prof. L. Mander, Australian National University; http://www.anu.edu.au) as internal standards for quantification. The concentrations of GAs in the extracts (three biological replicates) were determined using the calibration curves methodology.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Transcript levels were determined by absolute quantitative RT-PCR according to the methodology described in detail elsewhere (Serrani et al., 2008). Total RNA was isolated from ovaries using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit and Plant RNA Isolation Aid (Ambion, Applied Biosystems), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA, random hexamers, and a TaqMan RT kit (Ambion), with the following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, followed by 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 s. Aliquots of cDNA solutions were taken for quantitative RT-PCR using specific primers (Supplemental Table S1), Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, and a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Absolute quantification was carried out using external standard curves as described elsewhere (Olmos et al., 2005). Briefly, short PCR fragments (80–200 bp) of the sequences of interest were obtained using the specific primers indicated in Supplemental Table S1 (in this case, each forward primer also contained the T7 promoter sequence 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) and cDNA from specific clones for each analyzed gene. These PCR fragments, containing the T7 promoter, were purified from a 3% agarose gel using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and transcribed in vitro with the Megashortscript kit. Positive sense single-strand RNA (ssRNA) transcripts were treated with TURBO DNase to remove the DNA fragment used as template, purified by a glass filter-based system (MEGAClear kit), and used to synthesize first-strand cDNA as described before. Serial dilutions of cDNA solution corresponding to about 105 to108 molecules of ssRNA were used to set up external standard curves under identical amplification conditions to those used to amplify RNA targets from samples. Moles of ssRNA template were calculated by taking into account average ribonucleotide mass (340 g mol−1) and transcript base number (Nb) according to the following equation: pmol ssRNA = x pg ssRNA × (1 pmol/340 pg) × (1/Nb). Molecules of ssRNA were estimated using the Avogadro's constant (6.023 × 1023 molecules mol−1). Absolute amounts of mRNA in samples were quantified using three biological replicates.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AB015675 (SlCPS), AF049898 (SlGA20ox1), AF049899 (SlGA20ox2), AF049900 (SlGA20ox3), EU652334 (SlGA20ox4), AB010991 (SlGA3ox1), AB010992 (SlGA3ox2), EF441351 (SlGA2ox1), EF441352 (SlGA2ox2), EF441353 (SlGA2ox3), EF441354 (SlGA2ox4), and EF441355 (SlGA2ox5).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Scheme of the GA metabolic pathway.

Supplemental Figure S2. HPLC profiles of applied [3H]IAA and 3H radioactivity recovered in extracts from material collected 48 h after application of [3H]IAA to the ovary or apex.

Supplemental Figure S3. Images of representative MT, MT-SP, and MT-D plants at six-leaf (A) and at fruit-ripening (B) stages.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis of genes from GA metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas Moritz for help on IAA quantification and Dr. Jason W. Reed for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Abad M, Monteiro AA. (1989) The use of auxins for the production of greenhouse tomatoes in mild-winter conditions: a review. Sci Hortic 38: 167–192 [Google Scholar]

- Alabadí D, Agüero MS, Pérez-Amador MA, Carbonell J. (1996) Arginase, arginine decarboxylase, ornithine decarboxylase, and polyamines in tomato ovaries: changes in pollinated ovaries and parthenocarpic fruits induced by auxin and gibberellin. Plant Physiol 112: 1237–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangerth F. (1989) Dominance among fruits/sinks and the search for a correlative signal. Physiol Plant 76: 608–614 [Google Scholar]

- Bangerth F, Li CJ, Gruber J. (2000) Mutual interaction of auxin and cytokinins in regulating correlative dominance. Plant Growth Regul 32: 205–217 [Google Scholar]

- Banuelos GS, Bangerth F, Marschner H. (1987) Relationship between polar basipetal auxin transport and acropetal Ca2+ transport into tomato fruits. Physiol Plant 71: 321–327 [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EM, Quebedeaux B. (1974) Parthenocarpy in cucumber: mechanism of action of auxin transport inhibitors. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 99: 385–390 [Google Scholar]

- Bohner J, Hedden P, Bora-Haber E, Bangerth F. (1988) Identification and quantitation of gibberellins in fruits of Lycopersicon esculentum, and their relationship to fruit size in L. esculentum and L. pimpinellifolium. Physiol Plant 73: 348–353 [Google Scholar]

- Campos JL, Carvalho RF, Benedito VA, Peres LEP. (2010) Small and remarkable: the Micro-Tom model system as a tool to discover novel hormonal functions and interactions. Plant Signal Behav 5: 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell J, García-Martínez JL. (1980) Fruit-set of unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum L.: influence of vegetative parts. Planta 147: 444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clor MA. (1967) Translocation of tritium-labelled gibberellic acid in pea stem segments and potato tuber cylinders. Nature 214: 1263–1264 [Google Scholar]

- Coombe BG. (1962) The effect of removing leaves, flowers and shoot tips on fruit-set in Vitis vinifera L. J Hortic Sci 37: 1–15 [Google Scholar]

- Couillerot JP. (1981) Transport et devenir des molecules marquées après l'application du AG1-3H sur divers organs de Lycopersicon esculentum Mill: le rôle des fruits. C R Acad Sci Paris Ser III 292: 251–254 [Google Scholar]

- Davis TD, Curry EA. (1991) Chemical regulation of vegetative growth. Crit Rev Plant Sci 10: 151–188 [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Mariani C, Vriezen WH. (2009a) The role of auxin and gibberellin in tomato fruit set. J Exp Bot 60: 1523–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Wolters-Arts M, Feron R, Mariani C, Vriezen WH. (2009b) The Solanum lycopersicum Auxin Response Factor 7 (SlARF7) regulates auxin signalling during tomato fruit set and development. Plant J 57: 160–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Beveridge CA. (2006) Apical dominance and shoot branching: divergent opinions or divergent mechanisms? Plant Physiol 142: 812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund A, Eklöf S, Sundberg B, Moritz T, Sandberg G. (1995) A microscale technique for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry measurements of picogram amounts of indole-3-acetic acid in plant tissues. Plant Physiol 108: 1043–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet CM, Yamaguchi S, Hanada A, Kawaide H, David CJ, Kamiya Y, Sun TP. (2003) Overexpression of AtCPS and AtKS in Arabidopsis confers increased ent-kaurene production but no increase in bioactive gibberellins. Plant Physiol 132: 830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fos M, Nuez F, García-Martínez JL. (2000) The gene pat-2, which induces natural parthenocarpy, alters the gibberellin content in unpollinated tomato ovaries. Plant Physiol 122: 471–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fos M, Proaño K, Nuez F, García-Martínez JL. (2001) Role of gibberellins on parthenocarpic fruit-set in tomato induced by the genetic system pat-3/pat-4. Physiol Plant 111: 545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio M, Alabadí D, Pérez-Gómez J, García-Cárcel L, Phillips AL, Hedden P, Blázquez MA. (2006) Transcriptional regulation of gibberellin metabolism genes by auxin signalling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 142: 533–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Beltrán JP. (1992) Interaction between vegetative and reproductive organs during early fruit development in pea. Karssen CM, van Loon LC, Vreugdenhil D, , Progress in Plant Growth Regulation: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Plant Growth Substances. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 401–410 [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez JL, Hedden P. (1997) Gibberellins and fruit development. Tomás-Barberán FA, Robins RJ, , Phytochemistry of Fruit and Vegetables. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 263–286 [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy G, Ben-David H, Gruissem W. (1993) Fruits: a developmental perspective. Plant Cell 5: 1439–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Hooper LC, Johnson SD, Rodrigues JCM, Vivian-Smith A, Koltunow AM. (2007) Expression of aberrant forms of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 stimulates parthenocarpy in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Physiol 145: 351–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Vivian-Smith A, Johnson SD, Koltunova AM. (2006) AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 is a negative regulator of fruit initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1873–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorguet B, Van Heusden AW, Lindhout P. (2005) Parthenocarpic fruit development in tomato. Plant Biol 7: 131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Bangerth F. (1990) Diffusible IAA and dominance phenomena in fruits of apple and tomato. Physiol Plant 79: 354–358 [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto H, Shishido Y, Furuya S, Yasuba K. (1998) Growth and development of tomato fruit as affected by 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) applied to the peduncle. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci 67: 210–212 [Google Scholar]

- Homan DN. (1964) Auxin transport in the physiology of fruit development. Plant Physiol 39: 982–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IS, Okubo H, Fujieda K. (1992) Endogenous levels of IAA in relation to parthenocarpy in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Sci Hortic 52: 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- Koshioka M, Nishijima T, Yamazaki H, Nonaka M, Mander LN. (1994) Analysis of gibberellins in growing fruits of Lycopersicon esculentum after pollination or treatment with 4-chlorophenoxy-acetic acid. J Hortic Sci 69: 171–179 [Google Scholar]

- Leopold AC, Scott FI. (1952) Physiological factors in tomato fruit-set. Am J Bot 39: 310–317 [Google Scholar]

- Ljung K, Hull AK, Celenza J, Yamada M, Estelle M, Normanly J, Sandberg G. (2005) Sites and regulation of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 17: 1090–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli SC, Frova C, Torti G, Soressi G. (1978) Relationship between set, development and activities of growth regulators in tomato fruits. Plant Cell Physiol 19: 1281–1288 [Google Scholar]

- Martí C, Orzáez D, Ellul P, Moreno V, Carbonell J, Granell A. (2007) Silencing of DELLA induces facultative parthenocarpy in tomato fruits. Plant J 52: 865–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí E, Gisbert C, Bishop GJ, Dixon MS, García-Martínez JL. (2006) Genetic and physiological characterization of tomato cv Micro-Tom. J Exp Bot 57: 2037–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner R, Jacobson Y, Melamed S, Levyatuv S, Shalev G, Ashri A, Elkind Y, Levy AA. (1997) A new model system for tomato genetics. Plant J 12: 1465–1472 [Google Scholar]

- Morris DA, Friml J, Zazimalová E. (2004) The transport of auxins. Davies PJ, , Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 437–470 [Google Scholar]

- Ngo P, Ozga JA, Reinecke DM. (2002) Specificity of auxin regulation of gibberellin 20-oxidase gene expression in pea pericarp. Plant Mol Biol 49: 439–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olimpieri I, Siligato F, Caccia R, Mariotti L, Ceccarelli N, Soressi GP, Mazzucato A. (2007) Tomato fruit set driven by pollination or by the parthenocarpic fruit allele is mediated by transcriptionally regulated gibberellin biosynthesis. Planta 226: 877–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos A, Bertolini E, Gil M, Cambra M. (2005) Real-time assay for quantitative detection of non-persistently transmitted plum pox virus RNA targets in single aphids. J Virol Methods 128: 151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill DP, Ross JJ. (2002) Auxin regulation of the gibberellin pathway in pea. Plant Physiol 130: 1974–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro V, Leyser O. (2008) Hormonal control of shoot branching. J Exp Bot 59: 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozga JA, Yu J, Reinecke DM. (2003) Pollination-, development-, and auxin-specific regulation of gibberellin 3β-hydroxylase gene expression in pea fruit and seeds. Plant Physiol 131: 1137–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfini T, Molesini B, Spena A. (2007) Molecular dissection of the role of auxin in fruit initiation. Trends Plant Sci 12: 327–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfini T, Rotino GL, Camerini S, Defez R, Spena A. (2002) Optimisation of transgene action at the post-transcriptional level: high quality parthenocarpic fruits in industrial tomatoes. BMC Biotechnol 2: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretó JG, Beltrán JP, García-Martínez JL. (1988) The source of gibberellins in the parthenocarpic development of ovaries on topped pea plants. Planta 175: 493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan JD, Preston AP. (1971) The influence of shoot competition on fruit retention and cropping of apple trees. J Hortic Sci 46: 525–534 [Google Scholar]

- Ramin AA. (2003) Effects of auxin application on fruit formation in tomato growing under stress temperatures in the field. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 78: 706–710 [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo MJ, García-Martínez JL. (1998) Hormonal control of parthenocarpic ovary growth by the apical shoot in Pisum sativum L. Plant Physiol 116: 511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo MJ, López-Díaz I, García-Martínez JL. (1998) The characterization of gio, a new pea mutant, shows the role of indoleacetic acid in the control of fruit development by the apical shoot. Plant J 14: 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry KSK, Muir RM. (1965) Transport of indoleacetic acid in pedicels of tomato and its relation to fruit growth. Bot Gaz 126: 13–19 [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Fos M, Atarés A, García-Martínez JL. (2007a) Effect of gibberellin and auxin on parthenocarpic fruit growth induction in the cv Micro-Tom of tomato. J Plant Growth Regul 26: 211–221 [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fos M, García-Martínez JL. (2008) Auxin-induced fruit-set in tomato is mediated in part by gibberellins. Plant J 56: 922–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Sanjuan R, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fos M, García-Marínez JL. (2007b) Gibberellin regulation of fruit-set and growth in tomato. Plant Physiol 145: 246–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamas IA. (1995) Hormonal regulation of apical dominance. Davies PJ, , Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 572–597 [Google Scholar]

- Varga A, Bruinsma J. (1976) Roles of seeds and auxins in tomato fruit growth. Z Pflanzenphysiol 80: 95–104 [Google Scholar]

- Vriezen WH, Feron R, Maretto F, Keijman J, Mariani C. (2007) Changes in tomato ovary transcriptome demonstrate complex hormonal regulation of fruit set. New Phytol 177: 60–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Jones B, Li Z, Frasse P, Delalande C, Regad F, Chaabouni S, Latché A, Pech JC, Bouzayen M. (2005) The tomato Aux/IAA transcription factor IAA9 is involved in fruit development and leaf morphogenesis. Plant Cell 17: 2676–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Schauer N, Usadel B, Frasse P, Zouine M, Hernould M, Latché A, Pech JC, Fernie AR, Bouzayen M. (2009) Regulatory features underlying pollination-dependent and -independent tomato fruit set revealed by transcript and primary metabolite profiling. Plant Cell 21: 1428–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. (2008) Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 225–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsögön A, Lambais MR, Benedito VA, Figueira AVO, Peres LEP. (2008) Reduced arbuscular mycorhizal colonization in tomato ethylene mutants. Sci Agric 65: 259–267 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.