Abstract

Exposure to marital psychological and physical abuse has been established as a risk factor for children’s socio-emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems. Understanding the processes by which children develop symptoms of psychopathology and deficits in cognitive functioning in the context of marital aggression is imperative for developing efficient and effective treatment programs for children and families, and has far-reaching mental health implications. The present paper outlines our research program, Child Regulation and Exposure to Marital Aggression, which focuses on children’s emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation as pathways in the marital aggression–child development link. Findings from our research program, which highlight the importance of children’s regulatory processes for understanding children’s adjustment in contexts of intimate partner violence, are presented, and future directions in this line of inquiry are outlined.

Keywords: Marital violence, Marital aggression, Child adjustment, Physiological regulation, Vagal tone, Emotional reactivity

The negative impact of marital aggression and violence on children’s adjustment has been established; however, the processes that mediate these relations and variables that function as vulnerability or protective factors are poorly understood. Further, longitudinal research examining these associations is scarce. Marital psychological and physical aggression is prevalent in U.S. families, and understanding the processes by which marital violence affects children’s development across multiple domains of functioning has far-reaching mental health implications. The present paper describes our research program, Child Regulation and Exposure to Marital Violence, and presents a conceptual model for understanding the mechanisms by which marital violence affects children’s adjustment. We also present empirical evidence for our conceptual model. The main tenant of our research program is that examining children’s emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation to marital violence is not only critical for advancing our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the marital aggression–child adjustment link, but also offers a promising avenue for developing effective and efficient prevention and intervention efforts with children and families.

Prevalence Rates of Children’s Exposure to Marital Violence

While it is difficult to offer exact numbers regarding children exposed to marital violence, a commonly cited statistic is that some form of marital violence occurs in 12% of American households, and approximately 10 million children witness this violence per year (Straus and Gelles 1990). Current research, however, suggests that these statistics underestimate the number of children exposed to marital violence. For example, using a random digit dialing procedure, Smith Slep and O‘Leary (2005) assessed prevalence rates and patterns of aggression among married or cohabiting couples with at least one child between the ages of 3 and 7. Based on both partners’ reports of marital aggression, results indicated that some form of partner physical aggression was reported by 49% of couples, with 24% of these couples reporting severe physical aggression (e.g., beat up, burned, or scalded on purpose, kicked, slammed against a wall, choked, punched, or hit with an object that could hurt, used a knife or gun).

Not only are estimates of partner aggression higher than previously thought, but the number of children exposed to marital violence has also been previously underestimated. In a recent study, McDonald et al. (2006) estimated that 15.5 million children, or approximately 30%, live in homes in which some form of marital violence has occurred, and 13.3% of children live in homes in which at least one instance of severe partner violence has occurred during the past year. Alarmingly, due to the self-report nature of the study, the authors note that this study may still underestimate the number of children living in homes in which partner violence occurs. In an effort to provide a more accurate estimate of the number of children directly exposed to marital violence, Fantuzzo and Fusco (2007) worked with law enforcement investigators who were first responders to domestic violence events. The advantage of this methodology is that reports of physical violence are not based on participants’ reports of themselves or their partners. Additionally, police officers can assess whether children were present and whether they had sensory exposure (i.e., heard or saw) to the aggression. The results indicated that the most frequent type of violence was male-to-female aggression. Children were present in 44% of domestic violence events, and 58% of those children were below the age of six. The majority of children who were present during acts of marital violence (87%) had direct sensory exposure to the event. Taken together, this recent research highlights the prevalence of marital aggression in U.S. families, and that young children are disproportionately present and exposed to this violence. The effect of marital violence for children’s adjustment, therefore, is an important societal concern.

Marital Violence and Children’s Adjustment

Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence has implications for their emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological functioning (e.g., Jouriles et al. 1989; Kilpatrick and Williams 1997; Marks et al. 2001; Saltzman et al. 2005; Ybarra et al. 2007; see also Kitzmann et al. 2003 for review). Marital aggression also puts children’s physical safety at risk, such that partner violence in families increases the likelihood of parent-to-child aggression (Smith Slep and O‘Leary 2005).

Marital psychological abuse may account for additional unique variance in child functioning after controlling for the effects of physical aggression (Jouriles et al. 1996). Using an analog methodology in which children were exposed to simulated conflict scenarios, Cummings, El-Sheikh, and colleagues have found that children perceive physical interadult conflict as more angering and distressing than verbal marital altercations (e.g., Cummings et al. 1989; El-Sheikh and Cheskes 1995; Goeke-Morey et al. 2003; Harger and El-Sheikh 2003; Rieter and El-Sheikh 1999). Nevertheless, all forms of marital conflict, including physical, verbal, or covert (e.g., silent treatment) evoke negative affect and distress in children (Cummings et al. 2002; El-Sheikh and Reiter 1996 ; Rieter and El-Sheikh 1999 ). For a better understanding of child behavior problems and cognitive and academic performance in the context of family risk, child functioning needs to be examined in the context of both marital verbal/psychological and physical aggression.

Furthermore, marital aggression may have long lasting consequences for children’s functioning. For example, Cummings et al. (2007b) examined children’s responses to minor everyday marital disagreements in a community sample of families and found that controlling for current levels of marital aggression, previous levels of aggression moderated children’s responses. That is, children whose parents reported higher levels of aggression were more sensitive to positive conflict tactics during everyday marital disagreements, suggesting children exposed to marital violence track conflict for any evidence that parents are constructively working out their problems. These findings demonstrate that even low levels of marital aggression can impact children’s emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses to subsequent everyday marital disagreements 1 year later. This study underscores the need to examine not only concurrent relations between marital violence and children’s development, but also how marital violence effects children’s later adjustment. Further research, therefore, needs to be conducted investigating the longitudinal effects of marital violence for children’s outcomes. In particular, longitudinal studies are needed to address questions on how the timing of, and length of exposure to, marital violence differentially impacts children. Despite the implication of a temporal relationship between marital adjustment and children’s adjustment, the sparcity of longitudinal studies in this area limits our understanding of children’s developmental trajectories in the context of intimate partner violence.

Child Regulation and Exposure to Marital Conflict Research Program

The overall goal of our research program, Child Regulation and Exposure to Marital Conflict, is to advance our understanding of how and why marital aggression is related to children’s functioning across multiple domains. Two hundred and fifty-one families were recruited to participate in our study. Child participants (123 boys, 128 girls) were in the second or third grade and had a mean age of 8.23 years (SD = .73). Parents were married or had been living together for a substantial amount of time (M = 10 years, SD = 5.67). Most families in our study (73%) included both biological parents of children. The remaining families included a biological mother and step-father or live-in boyfriend (24%) or a biological father and step-mother (3%). Although marital aggression is a risk factor for child witnesses, there is great variability in child out-comes associated with marital violence, and not all children exposed to marital aggression experience negative consequences (e.g., Hughes and Luke 1998). This heterogeneity in child functioning in the context of marital aggression reinforces the need for research addressing processes linking, and moderators of, family and child development. The purpose of our research program is to address this gap in the marital violence and child development field.

Specifically, there are two primary goals of our research program: (1) examine children’s emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation as pathways and moderators of the association between marital psychological/verbal aggression and physical violence and children’s adjustment and cognitive and academic functioning and (2) identify child developmental trajectories associated with aggression and emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation. Consistent with the research agenda for the field of domestic violence and children outlined by Prinz and Feerick (2003), our research program examines physiological processes in relation to marital aggression, considers child characteristics (e.g., age, gender) and contextual factors (SES, ethnicity), and utilizes multiple reporters and methods of assessing marital violence.

There are several unique elements of our research program that are crucial for advancing our knowledge of the mechanisms underlying children’s developmental problems in the context of intimate partner violence. First, our research program moves beyond “first generation” research to identify the processes by which marital aggression leads to children’s socio-emotional and cognitive problems. It is important to note that this first generation of research was informative and valuable, highlighting the risk that interadult aggression has for children’s functioning. The necessary next step, however, is to move beyond correlations between risk and children’s outcomes in order to understand how and why negative family processes are related to children’s functioning (Cummings and Davies 2002). This level of analysis is critical for developing programs for children exposed to marital violence. Whereas education programs teaching couples how to constructively handle disagreements are effective (e.g., Cummings et al. 2008), understanding the mechanisms by which aggression affects children provides an additional avenue for targeting treatment programs that deal directly with children exposed to violence. In addition, our selection of the generative mechanisms examined in the marital aggression–child development link were based on theory and previous empirical research (discussed below), consistent with recognized recommendations for research in this area (e.g., Levendosky et al. 2007).

A second contribution of our research program is that we examine not only physical violence, but psychological or verbal aggression. Marital psychological/verbal abuse refers to threats, insults, and throwing objects. Distinguishing between different types of violence, and their effects on children, has been a gap in previous research (Holden 2003). Moreover, marital psychological abuse often precedes and co-occurs with physical violence (O‘Leary et al. 1994 ), and, therefore, examining multiple forms of conflict may better represent the social ecology of marital aggression to which children are exposed.

Third, consistent with research priorities in this area (Prinz and Feerick 2003), our program considers not only mediators, but moderators of the marital aggression–child development link. That is, our research program includes examination of which children are particularly vulnerable to developing symptoms of psychopathology in the context of marital aggression. We examine child characteristics, such as child age and gender, as well as individual difference variables such as parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) regulation. In addition, our research investigates aspects of the family context, including socio-economic status (SES) and ethnicity, in relation to the impact these variables have on the strength of the association between marital psychological and physical violence and children’s functioning. Thirty-four percent of our sample was African-American (AA; n = 89), and the remainder was European-American (EA; n = 162). Participants represented the entire range of SES levels (1 to 5) with M of 3.21 (SD = .91), based on Hollingshead (1975) criteria. We carefully recruited our sample to include families from a wide range of SES backgrounds, such that we could untangle the roles of SES and ethnicity on child functioning in the context of exposure to marital aggression. A fourth contribution is that we have followed families longitudinally to examine the effect of marital aggression not only on children’s concurrent functioning, but also on changes in children’s adjustment over time. We have recently completed our third wave of data collection. In this regard, we can investigate the effects of marital aggression on children’s developmental trajectories. For example, we can test whether children from homes with lower levels of marital aggression exhibit lower levels of symptomatology over time compared to children from homes with higher levels of marital aggression. Longitudinal research also allows for the possibility of examining which child characteristics and family context variables promote resiliency among children exposed to marital aggression. Fifth, our work examines a wide range of child outcomes, including functioning in emotional, behavioral, social, and physical health domains, as well as cognitive functioning and academic achievement.

Conceptual Model

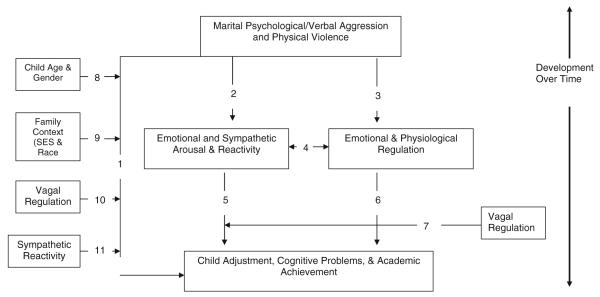

Our research program is rooted in an emotional regulation conceptual framework (Cummings and Davies 1996) and is guided by a biopsychosocial model of children’s development (El-Sheikh et al. in press). A framework for the regulatory processes mediating and moderating relations between intimate partner violence and child adjustment is presented in Fig. 1 and includes multiple pathways by which marital aggression and children’s outcomes may be related. As illustrated in the figure, children’s emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation are posited as generative mechanisms by which marital violence impacts children’s adjustment. Children’s responses to the stress of marital violence are viewed as mediating or moderating the effect of marital violence on children’s mental, cognitive/ academic and physical health problems.

Fig. 1.

A biopsychosocial model for the development of adjustment, cognitive, and academic problems in the context of marital psychological/ verbal aggression and physical violence

Consistent with other perspectives in this area (e.g., Cole et al. 2008), we view emotion regulation as more than simply a higher order reaction to the activation of emotional and physiological systems but also in terms of its operation as a component of emotional and physiological activation (Thompson et al. 2008). Moreover, from a theoretical perspective, the functioning of these behavioral and biological response processes, including emotional and physiological activation and regulation, is not simply to promote subjective well-being, but to also stabilize the organism’s functioning through reciprocal consolidation and coordination, toward goals of coherent organization as well as psychological well-being and health (Thompson et al. 2008).

With regard to what we mean by regulation in terms of physiological processes, we focus on two branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS): the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the PNS. The SNS and PNS are components of the human stress response. More specifically in terms of our conceptual model, intimate partner violence is hypothesized to have effects on neurobiological regulatory systems, including the PNS and SNS. Activity in these systems is hypothesized to contribute to pathways of effects in the link between marital conflict and violence and child outcomes. Both branches of ANS activity may influence children’s regulation of arousal, affect, and attention, and further function in concert, rather than in isolation, with each other. Patterns of vulnerabilities may be both inherited or acquired through experience (Steinberg and Avenevoli 2000). Moreover, ANS functioning may serve as a moderator (e.g., El-Sheikh et al. in press) as well as a mediator of relations between intimate partner violence and child adjustment. That is, ANS activity may also vary independent of intimate partner violence, exacerbating, or attenuating effects on children’s physical and mental health problems.

Direct Effects

Path 1 in the model is the direct link between marital psychological/verbal aggression and physical violence and children’s development. Direct effects are defined as those due to marital aggression, after accounting for the effects of other variables in the model. Direct effects likely reflect other mediating processes that were not included in our conceptual model. Whereas research has established a relationship between marital aggression and children’s adjustment, previous studies have assessed a narrow set of child outcomes, focusing primarily on behavioral and social problems (Cummings and Davies 2002). Theory and empirical data, however, suggest that marital aggression influences children’s cognitive processing (Moore and Pepler 1998; Rossman 1998). Investigations of associations between marital aggression and thorough assessments of cognitive processing are scarce. Therefore, our research program examines the relationship between marital aggression and a broader set of child outcomes, including cognitive functioning and academic achievement in addition to emotional and behavioral problems.

Mediating Effects

Paths 2 and 3, and 5 and 6 in the model depict children’s emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation, which are integral components of the Emotional Security Theory (Davies and Cummings, 1994), as intervening variables in the marital aggression–child development link. Emotional reactivity refers to the frequency and intensity of children’s expression of emotions. Physiological reactivity to a stressor is conceptualized as children’s SNS reactivity, and was assessed via electrodermal arousal and reactivity, including assessments of skin conductance level (SCL) and skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR), as well as cardiovascular arousal examined via pre-ejection period.

Previous research supports the proposition that heightened emotional reactivity mediates the relationship between marital aggression and children’s adjustment problems (Davies and Cummings 1998; Harold et al. 2004). For example, Lee (2001) found that higher levels of anger mediated the association between exposure to marital violence and children’s total behavior problems. High levels of negative emotionality in children in response to the stress of living in a home in which marital violence occurs, therefore, may develop into patterns of emotion dysregulation that in the extreme may result in symptoms of psychopathology (Cole et al. 1994). Further, high levels of emotional and physiological reactivity due to living in a maritally aggressive home may interfere with children’s cognitive functioning (see Rossman 1998). Although moderate levels of heightened arousal may be associated with better cognitive performance, high levels of arousal likely interfere with cognitive performance (McEwen and Margarinos 1997).

Emotion regulation is a dynamic process, with affective and physiological components, and includes processes of initiating, maintaining and modulating the occurrence, intensity, and/or duration of emotions, or emotion-related physiological processes (Eisenberg et al. 2000). The regulation of emotions is an adaptive process allowing one to match internal feeling states with environmental demands (Eisenberg et al. 2000; Thompson 1994). Physiological regulation, in our conceptual model, is a component of emotion regulation (Thompson 1994), and is assessed via PNS activity (vagal tone and suppression). Vagal tone and regulation are two common measures of PNS functioning, and are indexed in our studies by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). Vagal tone refers to baseline functioning, and vagal reactivity refers to changes in RSA from baseline to challenge conditions.

These mediated paths in the model are partly guided by the Emotional Security Theory (Davies and Cummings 1994). This theory posits that marital aggression threatens children’s set goal of wanting to feel secure in the family system, which motivates children’s regulatory responses. Thus, in our conceptual model, psychological/verbal aggression and marital violence impact children’s emotionality and its regulation, which in turn play a mediational role leading to adjustment difficulties (Davies and Cummings 1998). Although emotion reactivity and regulation are emphasized in models on the effects of marital conflict on children, these variables have been less studied in the family violence literature. Both marital psychological abuse and physical violence induce strong emotional responses in children, including higher levels of anger, sadness, and fear (Cummings et al. 2004, 2002; Davies and Cummings 1998; El-Sheikh 1997). We have expanded empirical assessments of the emotional security framework to include indices of children’s sympathetic (e.g., SCL) and parasympathetic (e.g., vagal regulation) arousal. Analog studies suggest that children respond to simulated conflict with cardiovascular and electrodermal reactivity (Ballard et al. 1993; El-Sheikh 2005a, b; El-Sheikh and Cummings 1992).

Path 4 in the model represents the fact that emotional and physiological reactivity and regulation are interrelated.

Moderating Effects

Moderation effects clarify which children are most likely to be at risk, and in which contexts, and thus are important for a process-oriented understanding regarding the effects of marital violence on children. Representing the complex pathways of effects that are likely present in the marital aggression–child adjustment link, ANS functioning may serve not only as a mediator, but also a moderator of effects, as depicted in Paths 7, 10, and 11. That is, we consider both the mediating and moderating role of vagal regulation and SCL reactivity to more fully explore the role of ANS functioning in the link between marital aggression and child development. Supporting the proposition that ANS functioning may also operate as moderator of risk, both vagal functioning and SCL stabilize in middle to late childhood (Calkins and Keane 2004; El-Sheikh 2005b; El-Sheikh 2007) reflecting individual differences among children in how they respond to stress. However, it is important to note that given the correlational nature of our longitudinal study, mediation and moderation were examined in a statistical sense.

Research supports that vagal regulation may moderate relations between marital aggression and children’s adjustment. El-Sheikh et al. (2001) found that greater vagal regulation was protective against externalizing and internalizing problems in the context of verbal/psychological marital aggression in a community sample of children ages 8–11. Similar findings were replicated in an independent sample of 6–11-year-old children (Whitson and El-Sheikh 2003). Additionally, individual differences have been found to moderate children’s internalizing and externalizing problems, and social competence in the context of other family stressors (e.g., paternal depression, Cummings et al. 2007a; El-Sheikh 2001, parental alcoholism). Furthermore, increased SNS reactivity was a vulnerability factor for girls’ externalizing problems associated with exposure to parental–marital conflict (e.g., El-Sheikh 2005b). Specifically, our conceptual model indicates that vagal regulation (Path 10) and sympathetic reactivity (Path 11) may moderate the direct link between marital psychological/verbal aggression and physical violence and children’s adjustment (Path 10), and/or it may moderate the mediated link among marital aggression, emotional and physiological reactivity, and children’s adjustment, also known as moderated mediation (Path 7; James and Brett 1984).

Other moderators included in the model are children’s age and gender (Path 8) and the family context, including ethnicity and SES (Path 9). Whereas age- and gender-related effects have been examined in studies investigating the effects of marital aggression on children’s outcomes, findings remain inconsistent (Gerard and Buehler 1999). That is, there is no clear consensus whether older as compared to younger children, or girls as compared to boys, are more strongly affected by marital aggression.

Associations between race/ethnicity and child functioning among children from high conflict homes have been little studied. In fact, only a small percentage of study samples have included both AA and EA families (McLoyd et al. 2001), and studies investigating ethnic differences in marital aggression have reported inconsistent findings. For example, whereas Gelles (1993) found increased incidences of marital aggression in AA families, in comparison to EA families, Vogel and Marshall (2001) did not find any differences when SES was taken into account. Drawing from the parenting literature, there is evidence to suggest that ethnicity may moderate associations. Deater-Deckard and colleagues (1997, 1996) found that physical discipline in early childhood predicted aggression for EA but not AA children.

Many studies on the marital violence–child adjustment link have investigated working or lower SES families. Jouriles et al. (1991) found that the relationship between marital aggression and child problems was stronger for lower, as compared to higher SES families. There is a recognized need in the literature to examine the effects of marital violence on child witnesses in not only lower, but also middle and upper-class families (NIH 2003, PAR-03-096).

Findings from our NIH-funded Research Program

The findings from our research program have examined direct, mediated, and moderated effects of intimate partner violence on children’s adjustment. Consistent with our conceptual model, our studies have examined children’s emotional and physiological responding as important process variables. Mothers, fathers, and children completed measures in the university laboratory. Given the sensitivity of some of the questionnaires with regard to marital violence, mothers and fathers completed measures in separate rooms. Children completed questionnaires with the help of an experimenter. Children also participated in a psycho-physiological assessment, in which the indices of the PNS and SNS were assessed (details on these procedures are available in El-Sheikh et al. in press).

Mediators and moderators of the marital aggression–child adjustment link

In our first study, we examined aggression against both mothers and fathers on children’s adjustment in multiple domains (El-Sheikh et al. 2008). Typically, studies on intimate partner violence have focused on aggression against the mother. Although not as distressing, aggression against the father, however, is also upsetting for children (Goeke-Morey et al. 2003). Marital aggression is likely reciprocal (Smith Slep and O‘Leary 2005), and Fantuzzo and Fusco (2007) noted that the effects of exposure to bidirectional aggression is an understudied area that should be addressed in future research. Not only did we study aggression against both parents, but our study examined multiple aspects of marital aggression, including acts and threats of physical violence, as well as psychological/verbal abuse. Our study, therefore, examined the unique effects of marital psychological and physical aggression against both the mother and father on children’s functioning in multiple domains. We examined a broad range of children’s out-comes, including internalizing and externalizing problems, symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems. Moreover, consistent with recommendations for research in this area, our study was theory-driven, extending the emotional security theory to more extreme forms of marital conflict. Our indices of emotional security included children’s emotional reactivity, behavioral regulation, and cognitive representations of the family in response to marital aggression. Therefore, this study provided a direct test of children’s reactivity and regulation as mediators of the link between marital aggression and children’s mental and physical health.

The findings indicated that aggression against either parent has unique effects for children’s emotional security. That is, controlling for aggression against the other parent, aggression against both mothers and fathers was related to increased levels of emotional insecurity (i.e., higher negative emotional reactivity, behavioral dysregulation, negative cognitive representations of the family). In turn, higher levels of emotional insecurity were related to higher levels of internalizing problems, symptoms of PTSD, and externalizing problems.

Consistent with our theoretical model, we also examined child characteristics (gender) and family context variables (ethnicity, SES) as moderators of the mediating effect of emotional security. That is, our moderated mediation models (James and Brett 1984) examined whether children’s reactivity and regulation (e.g., emotional security) was a stronger or weaker mediator in the association between marital aggression and child development in (1) girls compared to boys, (2) EA children compared to AA children, and (3) children from higher versus lower SES families. Generally, there were no differences among children based on gender, ethnicity, or SES. These results demonstrate the applicability of children’s regulatory processes, and more specifically their emotional security, for children of various ethnic and SES backgrounds.

SCLR as a Moderator of Harsh Parenting–Child Externalizing Problems Association

Given that marital aggression frequently co-occurs with parent-to-child aggression, we also extended our program of research to examine the unique effects of harsh parenting on children’s outcomes, controlling for marital conflict (Erath et al. in press). Harsh parenting was defined as coercive acts and negative emotional expression, which includes both verbal and physical aggression. Harsh parenting is a reliable correlate of children’s externalizing problems, and this study examined children’s physiological responding as an important process variable that may account for this relationship. Individual child characteristics, such as physiological responding, may shape psychological and behavioral outcomes. Guided by a biopsychosocial perspective, children’s sympathetic reactivity, as indexed by SCLR, was examined as a moderator of the link between harsh parenting and children’s externalizing problems. The rationale was that lower SCLR is a marker of low fearfulness and disinhibited behavior. Therefore, children with lower SCLR when faced with punishment may be insensitive to this form of discipline, making it ineffective. Rather, because of the low level of arousal, cognitive functioning among these children with lower SCLR is less disrupted and therefore they may be learning from their parents’ coercive and aggressive behavior. Children with higher SCLR, on the other hand, are more sensitive to harsh parenting. Therefore, harsh parenting is detrimental to all children; however, children with low SCLR may be learning and processing parents’ aggressive behavior more, making the link between aggression and children’s externalizing problems stronger.

The moderating role of SCLR in the association between harsh parenting and children’s externalizing behavior was examined using different reporters of harsh parenting (mothers, fathers, and children), and SCLR was assessed in different contexts (an interpersonal stress situation and a challenging task). Demonstrating the robustness of effects, the findings were consistent across reporters and contexts of SCLR assessment. As expected, in the context of harsh parenting, children with lower levels of SCLR exhibited higher levels of externalizing problems compared to children with higher levels of SCLR. No evidence for gender as a moderator was found.

Interactions Between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System Activity

A novel direction taken by our program of research is the examination of the coordination of the two branches of ANS, SNS and PNS, as a moderator of effects in the link between children’s exposure to marital aggression and their externalizing problems (El-Sheikh et al. in press). Despite the relatively robust nature of the association between marital aggression and externalizing problems, many children exposed to such aggression do not develop externalizing problems, and even among children who do exhibit externalizing behavior in the context of marital conflict, significant variability exists (Cummings and Davies, 2002). Steinberg and Avenevoli (2000) posited that individual differences in physiological responding might modulate the type and degree of maladjustment among children exposed to environmental stress such as marital conflict. That is, certain patterns of arousal and regulation, both inherited and acquired through experience, may operate as vulnerability or protective factors in the context of marital aggression. The SNS and PNS are key components of the human stress response system, and may be individual difference variables that increase or decrease susceptibility to externalizing problems associated with marital aggression.

Our previous studies have highlighted the role of the activity of either the SNS (El-Sheikh 2005b; El-Sheikh et al. 2007c) or the PNS (e.g., El-Sheikh and Whitson 2006) as intervening variables in the association between children’s responses to marital aggression and their externalizing behaviors. However, compared to the study of the activity of either system alone, simultaneously considering the activity of both ANS branches is likely to better account for the influence of marital aggression and physiological stress responses on behavioral adjustment. Indeed, investigations of physiological systems as independent entities are inevitably limited because physiological systems do not operate in isolation from one another. Rather, multiple physiological systems are in a perpetual process of coordinated fine-tuning to meet individual and environmental needs (Bauer et al. 2002). In the first such publication in the literature, we examined the coordination between the SNS and PNS as a moderator in the marital aggression–child externalizing behavior connection (El-Sheikh et al. in press; Study 2 in the Monograph). We expected that reciprocal activation (Berntson et al. 1991) in which both branches of the ANS promote the same directional response in a target system (e.g., ANS), will be associated with better adjustment in the context of family risk. Conversely, nonreciprocal activation refers to the condition in which the two branches of the ANS promote opposing responses in the broader ANS system. Because SNS and PNS actions serve opposing physiological functions, such parallel, or nonreciprocal, activation actually produces opposing physiological outcomes and was expected to yield increased vulnerability for externalizing problems in the context of marital aggression.

We examined children’s SNS activity through SCL and SCLR, and their PNS activity through RSA and RSA reactivity (RSAR). SCLR and RSAR were examined in two contexts (an interpersonal stress situation and a challenging task). The moderating role of interactions between SNS and PNS measures in the association between marital aggression and children’s externalizing behavior was examined using different reporters of marital aggression (mothers, fathers, and children), and child externalizing behavior was assessed via mothers’ and fathers’ reports. Results were supportive of hypotheses and indicated that opposing action of the PNS and SNS (i.e., nonreciprocal activation) operated as a vulnerability factor for externalizing behavior in the context of marital conflict, whereas reciprocal action of the PNS and SNS operated as a protective factor. This pattern of results did not differ for boys as compared to girls. The results provide compelling evidence in support of our biopsychosocial conceptualization of child adjustment, in which interactions between physiological systems involved in stress response moderate the association between marital aggression and child externalizing behaviors.

Summary of Key Findings and Contributions

A notable contribution of these studies is that multiple forms of aggression within the family were examined among community families, which may better capture the social ecology of aggression as it occurs in families. Physical and psychological aggressions were assessed, and the unique effects of aggression against both mothers and fathers were explored. Erath et al. (in press) examined parent-to-child aggression, controlling for marital aggression. Additionally, these studies were process-oriented, and guided by theory and prior empirical findings. Breaking new ground, our research program is one of the first to explore how the two branches of the ANS are interrelated with each other and emotional regulation and reactivity and may place certain children at increased risk for externalizing problems in the context of marital aggression. Consistent with our conceptual model, first, the findings demonstrate that children’s emotional reactivity operates as a mediator between marital psychological and physical abuse and multiple domains of children’s adjustment (Paths 2 and 5 in our model). Second, SNS reactivity (assessed via SCL) moderates the relationship between harsh parenting (another form of aggression within families, closely linked with marital aggression) and children’s externalizing problems (Path 11). Third, in a novel contribution to the field, our study has found that the two branches of the ANS, which are interrelated (Path 4), interact to predict children’s externalizing problems (Path 7). Fourth, we have examined child (gender, Path 8), and family (SES, ethnicity, Path 9) characteristics as moderators of our meditational model and as of yet have not found support for differential effects based on these variables. Although we have made progress in testing our conceptual model across a series of programmatic studies, fully exploring this model remains an ongoing effort.

Ongoing Directions from the Research Program: Longitudinal Follow-up Studies

Several ongoing projects utilizing the data from our ongoing NIH-funded study have significant potential to advance our prior cross-sectional studies, by investigating child regulation and developmental outcomes in the context of family aggression using multi-wave (i.e., three-wave) longitudinal data. Longitudinal data provide unique opportunities to study the intervening role of child regulatory processes linking marital aggression with child outcomes, through methods that are more rigorous than cross-sectional methods, and allow tests of stability or change in marital aggression, child developmental out-comes, processes leading to child outcomes, and their correlates. Additionally, this longitudinal approach allows for the strongest argument for causality that can be made in nonexperimental research: the requirements of correlation, time precedence, and the control of possible confounds have been met to the greatest extent possible. These follow-up studies that are presently in preparation will thus reinforce our prior cross-sectional research and answer questions that require longitudinal data. For example, in an aforementioned recent cross-sectional investigation, El-Sheikh et al. (2008) provided new evidence for emotional insecurity as a mediator linking marital violence with children’s internalizing, externalizing, and PTSD symptoms. In an ongoing follow-up study, more rigorous tests of mediation and directionality will be conducted via autoregressive, cross-lagged statistical models using three-waves of data.

In other cross-sectional studies using the NIH data, Erath et al. (in press) found that SCLR moderated the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior, and El-Sheikh et al. (in press) reported that interactions between PNS and SNS activity moderated the association between marital aggression and child externalizing behavior. Longitudinal follow-up studies are critical, to examine whether these interactions among family aggression and indices of physiological regulation predict changes in children’s externalizing behavior and other facets of adjustment over time. We are also in the process of examining children’s cognitive performance and academic achievement over time in the context of exposure to parental–marital and parent–child psychological and physical aggression. Assessments of children’s cognitive and academic functioning in the context of family aggression are scarce and our rich data set will allow for an explication of specific cognitive functioning and academic domains (e.g., executive functioning, performance on standardized achievement tests) that may be most affected by exposure to familial aggression.

Clinical Implications

The findings from our research program thus far indicate that children’s regulatory processes, both emotional and physiological, are important pathways through which marital aggression affects children’s development. Children with high levels of negative emotional reactivity (anger, sadness, fear), behavioral dysregulation, and lower PNS activity, may be particularly vulnerable to developing symptoms of psychopathology in the context of marital aggression and harsh parenting. It remains to be tested how these relationships change over time, and the consequences of certain patterns of emotional and physiological responding and regulation for children’s adjustment over time. Nevertheless, the importance of children’s reactivity and regulation for their development in the context of marital aggression has implications for treatment and intervention programs. In addition to programs for couples aimed at reducing marital and family aggression and violence, programs can also be developed that deal directly with children exposed to aggression (e.g., Cummings et al. 2008). That is, treatment programs can be developed such that clinicians can work directly with children to develop effective and safe coping strategies for children to deal with the stress of exposure to marital aggression. These coping strategies should be based on regulating children’s negative emotional and physiological responses that are adaptive for them not only in the short-term, but also adaptive for their long-term functioning. For example, Wolchik and colleagues (2000, 2002) found only limited support for the additive benefit of a child component program that attempted to change children’s coping skills in relation to adjustment and marital conflict and divorce. At the same time, a program that took into account child effects with regard to individual differences in emotional and physiological reactivity may be able to target, which lessons to emphasize in teaching children to cope with marital conflict. Findings from our research program, which indicate significant individual differences in children’s patterns of emotional and physiological reactivity to marital conflict and other family stressors, suggest that this is a promising direction toward more effective programs for ameliorating the negative effects of violence on children, that is, fine-tuning programs to suit children’s individual response dispositions.

Next Steps in This Research Direction

Knowledge gained through data collected for this grant broke new ground in understanding processes and intervening variables in the link between exposure to marital aggression and a wide range of child development out-comes including adjustment, cognitive functioning, and academic performance. However, several important gaps in knowledge remain. The three-waves of data collected constitute a rich data set for investigating developmental outcomes in the context of psychological and physical marital aggression. However, three-waves of data do not allow for examinations of nonlinear trajectories of development. Thus, further assessments of the role of regulatory processes (mediators, moderators) in the context of multiple forms of marital aggression through more waves of data are likely to clarify developmental trajectories of child adaptation and maladaptation over time. Additional analyses with at least four waves of data will not only enable the examination of nonlinear trajectories but will also allow for the exploration of the prominence of associations among model variables during earlier versus later waves (e.g., Is mediation or moderation stronger for certain developmental periods? Is the relation between T1 marital aggression and T2 child outcomes similar to that between T4 aggression and T5 outcomes?). Further, the direction of effects among model variables could also be examined over a longer developmental period (e.g., Is the relation between T1 marital aggression and T5 child outcomes stronger than that between pertinent outcomes at T1 and T5 marital aggression?). To accomplish this, multipanel structural equation modeling would be instrumental. Models can also be examined in reverse direction of effects (e.g., child outcomes as predictors of marital aggression) to determine whether one construct is a “leading cause” (Schermerhorn et al. 2007).

In addition, further longitudinal follow-up studies over a longer time frame could begin to answer intriguing developmental questions that build on our prior cross-sectional and longitudinal studies with fewer waves of data. For example, it is possible that children’s physiological responses are more influential as vulnerability or protective factors (i.e., moderator) in adolescence versus childhood. Importantly, further follow-ups would allow addressing these questions during a developmental period that is characterized by significant biological changes (e.g., puberty) as well as other environmental challenges (e.g., school transitions), and that immediately precedes the well-documented increase in internalizing and externalizing problems around the transition to adolescence.

Another important avenue for future research is the investigation of other child outcome domains that may be impacted by multiple facets of marital aggression, including children’s sleep and immune system functioning. El-Sheikh, Buckhalt, and colleagues’ previous research supports the importance of family functioning for children’s sleep disruptions. In a study funded by NSF, we found that a higher level of emotional security in the parental–marital relationship functioned as an intervening variable in the association between children’s exposure to marital conflict and their sleep problems, adjustment (e.g., El-Sheikh et al. 2007a) and academic achievement (El-Sheikh et al. 2007b). In another publication, we reported links between marital conflict and sleep in children (El-Sheikh et al. 2006). Family conflict has also been implicated as a predictor of later insomnia (Gregory et al. 2005), and links between stress, including marital conflict, and sleep are reported (Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001). Thus, further inclusion of facets of biological regulation will help clarify how children’s sleep parameters (amount, quality) are influenced by marital psychological and physical aggression. For example, SCLR may constitute a child effect that moderates risk for adjustment problems in the context of family stresses, such as parental dysphoria and marital conflict, with implications for children’s sleep disruptions and immune system functioning (Cummings et al. 2007). Additionally, links with children’s internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety) (Cummings et al. 2006) and cognitive functioning (Harold et al. 2007) have been limited and study of relations with these outcomes is an important future direction for research.

Another potentially fruitful avenue for research builds on findings from the NIH data set regarding reciprocal activation of the SNS and PNS as a protective factor, and nonreciprocal activation as a vulnerability factor, in relation to children’s externalizing behaviors in the context of marital aggression. Our present studies did not link physiological response patterns with measured cognitive or behavioral coping responses, and this linkage is an open scientific question. ANS activity and reactivity are likely associated with emotional reactivity and regulation, and empirical assessments of this proposition in the context of exposure to marital aggression are likely to move the field forward. Future research that specifically links physiological activity and reactivity with behavioral coping responses, in particular, would be informative for interventions designed to protect children from exposure to marital aggression and violence.

Conclusions

The integration of study of biological and psychological processes in children’s responses to intimate partner violence over time is a signature characteristic of this NIH-funded research program, addressing important gaps pertinent to future directions in clinical child and developmental research. The findings of this research program highlight the urgent need to understand physiological as well as psychological processes that may mediate or moderate the impact of marital aggression on multiple dimensions of child functioning and adjustment. In addition, this work underscores the need to ground research in well-defined and delineated theoretical models that can accommodate and incorporate multiple domains of children’s physiological and psychological processes, and how these factors interrelate, as well as the prediction of multiple dimensions of children’s functioning beyond psychological adjustment, for example, school performance and sleep problems. Moreover, the results emphasize the value of incorporating multiple family processes and stressors in examining the effects of marital aggression on children’s development, including parent–child and interparental relationships. For example, recent work suggests that understanding trajectories of children’s emotional security processes over time is better informed by taking into account multiple family stressors (e.g., parental depression and marital conflict, Kouros et al. 2008). Important next steps include further investigation of these issues in the context of longitudinal model testing, which will enable more certain inferences about the nature of causal processes, as well as the opportunity for breaking new ground in tracking important developmental changes and trajectories in child functioning over time in these contexts. These next steps in this research direction will allow us to better identify processes of risk, including long-term implications of risk processes, as well as resilience and protective factors, with the potential to better inform future clinical intervention and prevention efforts regarding children’s exposure to marital conflict and violence (Cummings et al. 2008). Finally, the long-term goal of this NIH-funded research program, and related projects, is contributing toward the advancement of a truly biopsychosocial model of children’s development in the context of violence.

Contributor Information

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA.

Mona El-Sheikh, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Chrystyna D. Kouros, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA

Joseph A. Buckhalt, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

References

- Ballard M, Cummings EM, Larkin K. Emotional and cardiovascular responses to adults’ angry behavior and challenging tasks in children of hypertensive and nomotensive parents. Child Development. 1993;64:500–515. doi:10.2307/1131265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Quas JA, Boyce WT. Associations between physiological reactivity and children’s behavior: Advantages of a multisystem approach. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23(2):102–113. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Quigley KS. Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review. 1991;98:459–487. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.4.459. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation across the preschool period: Stability, continuity, and implications for childhood adjustment. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45(3):101–112. doi: 10.1002/dev.20020. doi:10.1002/dev.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Luby J, Sullivan MW. Emotion and development of childhood depression: Bridging the gap. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2(3):141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Keller PS. Children’s skin conductance reactivity as a mechanism of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2007a;48(5):436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01713.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Faircloth WB, Mitchell PM, Cummings JS, Schermerhorn AC. Evaluating a brief prevention program for improving marital conflict in community families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:193–202. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.193. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:191–202. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019770.13216.be. doi:10.1023/B:JACP.0000019770.13216.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM, Dukewich TL. Children’s responses to mothers’ and fathers’ emotionality and tactics in marital conflict in the home. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:478–492. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Kouros CD, Papp LM. Marital aggression and children’s responses to everyday interparental conflict. European Psychologist. 2007b;12:17–28. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.12.1.17. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77(1):132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Vogel D, Cummings JS, El-Sheikh E. Children’s responses to different forms of expression of anger between adults. Child Development. 1989;60:1392–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04011.x. doi:10.2307/1130929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Exploring children’s emotional security as a mediator of the link between marital relations and child adjustment. Child Development. 1998;69:124–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0803_1. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Petit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1065. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Children’s responses to adult–adult and mother–child arguments: The role of parental marital conflict and distress. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:165–175. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.11.2.165. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Parental drinking problems and children’s adjustments: Vagal regulation and emotional reactivity as pathways and moderators of risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:499–515. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Stability of respiratory sinus arrhythmia in children and young adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Development and Psychopathology. 2005a;46:66–74. doi: 10.1002/dev.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. The role of emotional responses and physiological reactivity in the marital conflict-child functioning link. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2005b;46:1191–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00418.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Children’s skin conductance level and reactivity: Are these measures stable over time and across tasks? Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49:180–186. doi: 10.1002/dev.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt J, Cummings EM, Keller P. Sleep disruptions and emotional insecurity are pathways of risk for children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2007a;48:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01604.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt J, Cummings EM, Keller P, Acebo C. Child emotional insecurity and academic achievement: The role of sleep disruptions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007b;21:29–38. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.29. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt J, Mize J, Acebo C. Marital conflict and disruption of children’s sleep. Child Development. 2006;77:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh E, Cheskes J. Background verbal and physical anger: A comparison of children’s responses to adult–adult and adult–child arguments. Child Development. 1995;66:446–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00882.x. doi:10.2307/1131589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM. Availability of control and preschoolers’ responses to interadult anger. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1992;15:207–226. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh E, Cummings EM, Kouros CD, Elmore-Staton L, Buckhalt J. Marital psychological and physical aggression and children’s mental and physical health: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:138–148. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Keller PS, Erath SA. Marital conflict and risk for child maladjustment over time: Skin conductance level reactivity as a vulnerability factor. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007c;35:715–727. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9127-2. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Erath S, Cummings EM, Keller P, Staton L. Marital conflict and children’s externalizing behavior: Interactions between parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system activity. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00501.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Reiter SL. Children’s responding to live interadult conflict: The role of form of anger expression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:401–415. doi: 10.1007/BF01441564. doi:10.1007/BF01441564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:30–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath SA, El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM. Child Development. Harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior: Skin conductance level reactivity as a moderator. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, Fusco RA. Children’s direct exposure to types of domestic violence crime: A population-based investigation. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:543–552. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9105-z. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ. Through a sociological lens: Social structure and family violence. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DR, editors. Current controversies on family violence. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Buehler C. Multiple risk factors in the family environment and youth problem behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Harold GT, Shelton KH. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, Moffitt TE, O’Connor TG, Pouton R. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-1824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harger J, El-Sheikh M. Are children more angered and distressed by man-child than woman-child arguments and by interadult versus adult–child disputes? Social Development. 2003;12:162–181. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00227. [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Aitken JJ, Shelton KH. Interparental conflict and children’s academic attainment: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1223–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Shelton KH, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships and child adjustment. Social Development. 2004;13:350–376. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00272.x. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW. Children exposed to domestic violence and child abuse: Terminology and taxonomy. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:151–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1024906315255. doi:10.1023/A:1024906315255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. 1975. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hughes HA, Luke DA. Heterogeneity in adjustment among children of battered women. In: Jouriles EN, Holden GW, Geffner R, editors. Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 185–221. [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Brett JM. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 1984;69:307–321. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.307. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Bourg WJ, Farris AM. Marital adjustment and child conduct problems: A comparison of the correlation across subsamples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:354–357. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.354. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Murphy CM, O‘Leary KD. Interspousal aggression, marital discord, and child problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:453–455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.3.453. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Norwood WD, McDonald R, Vincent JP, Mahoney A. Physical violence and other forms of marital aggression links with children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:223–234. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.223. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick KL, Williams LM. Post-traumatic stress disorder in child witnesses to domestic violence. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;50:686–696. doi: 10.1037/h0080261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witness of domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros CD, Merriless CE, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and children’s emotional security in the context of parental depression. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2008;70:684–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00514.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. Marital violence: Impact on children’s emotional experiences, emotional regulation, and behaviors in a post-divorce/separation situation. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2001;18:137–163. doi:10.1023/A:1007650812845. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, von Eye A. New directions for research on intimate partner violence and children. European Psychologist. 2007;12:1–5. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.12.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Marks CR, Glass BA, Horne JB. Effects of witnessing severe marital discord on children’s social competence and behavior problems. The Family Journal (Alexandria, Va.) 2001;9:94–101. doi:10.1177/1066480701092002. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Margarinos M. Stress effects on morphology and function of the hippocampus. In: McFarlane AC, Yehuda R, editors. Psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. New York Academy of Sciences; New York, NY: 1997. pp. 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Harper CI, Copeland NL. Ethnic minority status, interparental conflict, and child adjustment: Theory, research, and application. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 98–125. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TE, Pepler DJ. Correlates of adjustment in children at risk. In: Jouriles EN, Holden GW, Geffner R, editors. Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 157–184. [Google Scholar]

- NIH Research on children exposed to violence. 2003. PAR-03-096.

- O‘Leary KD, Malone J, Tyree A. Physical aggression in early marriage: Prerelationship and relationship effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:594–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.594. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Feerick MM. Next steps in research on children exposed to domestic violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:215–219. doi: 10.1023/a:1024966501143. doi:10.1023/A:1024966501143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieter SL, El-Sheikh M. Does resolution of interadult conflict ameliorate children’s anger and distress across covert, verbal, and physical disputes? Journal of Emotional Abuse. 1999;1:1–21. doi:10.1300/J135v01n03_01. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BBR. Descartes’s error and posttraumatic stress disorder: Cognition and emotion in children who are exposed to parental violence. In: Jouriles EN, Holden GW, Geffner R, editors. Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 223–256. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman KM, Holden GW, Holahan CJ. The psychobiology of children exposed to marital violence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:129–139. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_12. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, Cummings AC, DeCarlo CA, Davies PT. Children’s influence in the marital relationship. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):259–269. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.259. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep AM, O‘Leary SG. Parent and partner violence in families with young children: Rates, patterns, and connections. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:435–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. The role of context in the development of psychopathology: A conceptual framework and some speculative propositions. Child Development. 2000;71(1):66–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8, 145 families. Transaction Publications; NJ: 1990. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:25–52. doi:10.2307/1166137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Lewis MD, Calkins SD. Reassessing emotion regulation. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2(3):124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel LCM, Marshall LL. PTSD symptoms and partner abuse: Low income women at risk. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:569–584. doi: 10.1023/A:1011116824613. doi:10.1023/A:1011116824613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson SM, El-Sheikh M. Moderators of family conflict and children’s adjustment and health. Journal of Emotional Abuse: Interventions, Research and Theories of Psychological Maltreatment, Trauma, and Nonphysical Aggression. 2003;31:47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Plummer BA, Greene SM, Anderson ER, et al. Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1874–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1874. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Coatsworth D, Lengua L, et al. An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:843–856. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra GJ, Wilkens SL, Lieberman AF. The influence of domestic violence on preschooler behavior and functioning. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:33–42. doi:10.1007/s10896-006-9054-y. [Google Scholar]