Abstract

The mechanism of inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 (CYP2B1) by 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene (BPA) has been characterized previously to be caused by the covalent binding of a reactive intermediate to the apoprotein rather than heme destruction (J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:392–403, 2009). The identification of a BPA-glutathione conjugate and the increase in the mass of the BPA-adducted apoprotein have indicated that the mass of adduct is 174 Da, equivalent to the mass of BPA plus one oxygen atom. To identify the adducted residue, BPA-inactivated CYP2B1 was digested with trypsin, and the digest was then analyzed by using capillary liquid chromatography with a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer as the detector. A mass shift of 174 Da was used for a SEQUEST database search. The tandem mass spectrometry fragmentation of the modified peptide and the identity of modified residue were determined. The results revealed a mass increase of 174 Da for the peptide sequence 296FFAGTSSTTLR308 in the I-helix of CYP2B1 and that the site of adduction formation is Thr302. Homology modeling and ligand docking studies showed that BPA binds in close proximity to both the heme iron and Thr302 with the distances being 2.96 and 3.42 Å, respectively. The identification of Thr302 in the CYP2B1 active site as the site of covalent modification leading to inactivation by BPA supports previous hypotheses that this conserved Thr residue may play a crucial role for various functions in P450s.

A number of acetylenic compounds have been shown to be effective mechanism-based inactivators of various cytochrome P450s in rat liver microsomes or purified reconstituted systems (Roberts et al., 1993, 1995; Foroozesh et al., 1997; Blobaum et al., 2002; Kent et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2002). Because the mechanism for the inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 (CYP2B1) by 2-ethynylnaphthalene (2EN) and 9-ethynylphenanthrene (9EP) involved covalent binding of the acetylenic compound to apoprotein rather than to the prosthetic heme moiety, these acetylenes proved to be especially useful for the identification of modified peptides at the active site of P450s (Roberts et al., 1993, 1994, 1995). By using radiolabeled 2EN and 9EP as mechanism-based inactivators in the CYP2B1 reconstituted system and digesting the P450s with Lys C, trypsin, pepsin, or cyanogen bromide, the modified peptides were analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS) and sequenced on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The results indicated that 2EN is adducted to a peptide with a sequence corresponding to positions 290–314 in CYP2B1 and 9EP is adducted to a peptide with a sequence corresponding to positions 297–307 in CYP2B1. Both of these studies indicated that the modified residue is in the I-helix with the mass increase being equal to the addition of one molecule of inactivator plus one oxygen atom, and it was suggested that one of the Thr or Ser residues in the peptides was the site where 2EN or 9EP covalently modified the peptide. In several experiments with inactivated CYP2B1, the last residue that could be sequenced was the Glu301 that precedes Thr302, suggesting that Thr302 could be the modified residue. Thr302 in CYP2B1 corresponds to Thr252 in P450 101 and Thr268 in P450 102 (Poulos, 1991; Ravichandran et al., 1993; Hasemann et al., 1995). It has been proposed that Thr252 in CYP101 and Thr268 in CYP102 are essential parts of a proton relay pathway that donates protons to the dioxygen bound to the reduced heme iron during catalysis (Raag et al., 1991; Ravichandran et al., 1993). Moreover, site-directed mutagenesis of amino acids in this region has demonstrated the importance of Thr301 in catalysis of rabbit 2C2 and 2C14 (Imai and Nakamura, 1988), Thr303 in rabbit CYP2E1 (Fukuda et al., 1993), Thr302 in rat CYP2B1 (He et al., 1994), and Thr303 in CYP2A1/2A2 (Hanioka et al., 1992). Roberts et al. (1994, 1995) postulated that the covalent modification by 2EN and 9EP occurs by reaction of the hydroxyl group of Thr302 with a ketene intermediate of the acetylenic inactivator formed by the P450-catalyzed oxygenation of the acetylene (Ortiz de Montellano and Kunze, 1981; Ortiz de Montellano and Komives, 1985). However, the identity of the residue modified in CYP2B1 by 2EN and 9PN in the peptide has not yet been unequivocally determined. By using a radiolabeled compound in conjunction with liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS), our laboratory has recently identified Ser360 in CYP2B1 as the site modified by 17α-ethynylestradiol (Kent et al., 2008).

We have previously demonstrated that: 1) the inactivation of CYP2B1 by 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene (BPA) is very efficient and heme destruction does not contribute to the mechanism of inactivation, 2) BPA forms a covalent adduct with the CYP2B1 apoprotein with a mass increase of 174 Da, and 3) isolation and MS analyses of the BPA-glutathione (GSH) conjugate reveals a mass shift of 174 Da for the GSH adduct with the reactive metabolite (Lin et al., 2009). It is now feasible to identify sites of adduct formation in apoproteins without the requirement for radiolabeled compounds by using proteomics approaches. BPA-modified CYP2B1 was digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The mass shift of 174 Da observed after adduction of the apoprotein, and also for the GSH conjugate, was used to identify the modification site by using the SEQUEST database search.

Based on the crystal structure of CYP2B4 (Scott et al., 2004), a CYP2B1 homology model was constructed, BPA was docked into the CYP2B1 active site, and the predictions from the docking studies were tested experimentally. The distances between the heme iron and the three residues that were suggested to be adducted by the SEQUEST search were examined.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Catalase, NADPH, GSH, l-α-dilauroyl-phosphatidylcholine, BPA, and trifluoroactic acid (TFA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mass spectrometry-grade trypsin was from Promega (Madison, WI). All other chemicals and solvents were of the highest purity available from commercial sources.

Preparation of Modified Apoprotein.

The CYP2B1 and reductase were expressed in Escherichia coli TOPP3 cells and purified according to previously published procedures (Lin et al., 2003). Samples containing 500 pmol of CYP2B1 were reconstituted with 500 pmol of reductase, 50 μg of l-α-dilauroyl-phosphatidylcholine, 2 mM GSH, 50 units of catalase, and 2 μM BPA in the absence (control) or presence (inactivated) of 1 mM NADPH in 500 μl of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) at 22°C for 10 min. After the inactivation, the reaction mixtures were denatured by 8 M urea at 60°C for 30 min followed by exchanging the buffer with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0) using Amicon Ultra centrifuge filter devices (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Aliquots (100 μl) of the concentrated samples were reduced by using 5 mM dithiothreitol and then digested with 2 μg of trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 37°C for 18 h. The digested peptides were centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min, and the clear supernatants were subjected to analysis by mass spectrometry.

Capillary LC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions.

A Waters (Milford, MA) capillary LC system connected to a ThermoFinnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used. Aliquots (25 μl) of the digested peptide samples were loaded onto a reversed-phase XBridge BEH300 C18 capillary column (3.5 μm, 0.3 × 150 mm NanoEase column; Waters). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (0.05% formic acid and 0.05% TFA in H2O) and solvent B (0.05% formic acid and 0.05% TFA in acetonitrile). Separation of the peptides was accomplished by using a linear gradient of 2% B to 50% B over 95 min followed by 50% B to 100% B for another 5 min at a flow rate at 5 μl/min. The column effluent was directed into the LTQ mass analyzer. The electrospray ionization conditions were: 4 kV for the spray voltage, 300°C for the capillary temperature, 47 V for the capillary voltage, 100 V for the tube lens, 30 arbitrary units for the sheath gas, and 5 arbitrary units for the auxiliary gas. Data were acquired in positive mode by using Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in data-dependent experiments where MS/MS data were collected on the 10 most abundant ions in the survey scan.

SEQUEST Database Search.

Modified peptides were identified based on the cross-correlation (XCorr) score, reflecting the quality of the match between an experimental and a database-predicted MS/MS spectrum (Bioworks, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Scores higher than 2.0, 2.5, and 3.6 for singly, doubly, and triply charged peptide precursor ions, respectively, were considered to be significant and verified by inspection of the fragmentation patterns. The probability score, a scoring algorithm in BioWorks software that is based on the probability that the peptide is a random match to the spectral data, was considered meaningful when it was less than 1 × 10−3. The observed peptide masses were exported to the SEQUEST software in BioWorks3.3.1 and compared with the theoretical masses for the CYP2B1 peptides from ProteinProspector software (http://prospector.ucsf.edu) using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. On the basis of the hypothesis that the insertion of an oxygen at the terminal carbon of an ethynyl moiety leading to an electrophilic ketene intermediate will result in the covalent modification of the apoprotein, the nucleophilic residues most likely to react with the carbonyl moiety to form a stable bond would be Thr, Ser, Tyr, Cys, and Lys (Roberts et al., 1993).

Docking of BPA into the CYP2B1 Active Site.

BPA was docked into the active site of CYP2B1 by using the energy-based docking software of AutoDock (version 4.0) (Morris et al., 1996). A homology model of CYP2B1 was constructed based on a template of the CYP2B4 crystal structure (Protein Data Bank ID code 1SUO) (Scott et al., 2004). The coordinates of BPA were built with ChemBioOffice 2008 (CambridgeSoft Corporation, Cambridge, MA), and the lowest energy conformations were obtained by the AM1 method. The flexible BPA was docked into the rigid CYP2B1 by using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm approach of AutoDock with the following parameters: mutation rate 0.02; crossover 0.80; maximal number of generations 2.7 × 107; and local search frequency 0.06. The distances from the amino acid residues to the heme iron and BPA were determined by using PyMOL software (www.pymol.org).

Results

Purified CYP2B1 was inactivated by incubation with BPA under turnover conditions, the inactivated CYP2B1 was digested with trypsin, and the tryptic peptides were analyzed as described under Materials and Methods. The modification of neuclophilic residues in the active site of CYP2B1 by the addition of a reactive metabolite formed from BPA would be expected to result in a mass shift of 174 Da. A SEQUEST search using this mass shift suggested two modified peptides for the BPA-modified sample, but none were identified in the control sample. The search results are shown in Table 1. The two modified peptides correspond to residues 296–308 (FFAGTETSSTTLR) and residues 100–109 (TIAVIEPIFK). The MS/MS spectra of the modified peptides were further analyzed with Xcalibur software and compared with the theoretical fragmentations of modified peptides by using ProteinProspector software to confirm the modified peptide sequence and the identity of residues modified by BPA.

TABLE 1.

Results of a SEQUEST (BioWorks 3.30.1) database search of a trypsin digest of BPA-inactivated CYP2B1

| Modified Peptide Sequence | Modified Residue | Precursor Ion Charge | XCorra | Probabilityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 | Thr302 | 2 | 3.62 | 1.7 × 10−6 |

| 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 | Ser303 | 2 | 3.48 | 1.1 × 10−4 |

| 100TIAVIEPIFK109 | Thr100 | 2 | 2.90 | 8.0 × 10−5 |

XCorr value between the observed peptide fragment mass spectrum and the one theoretically predicted.

Probability: scoring algorithin in the BioWorks software program based on the probability that the peptide is a random match to the mass spectral data.

MS/MS Analysis of the BPA-Modified 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 Peptide.

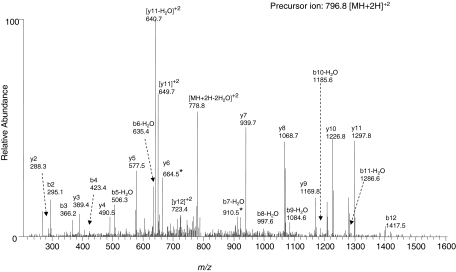

The reaction of the reactive metabolite of BPA to form an adduct at either Thr302 or Ser303 in the peptide sequence 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 giving a MH+ ion at m/z 1592.5 was suggested by the SEQUEST database search. The search indicated adduct formation at Thr302 with an XCorr score of 3.62 and a probability of 1.7 × 10−6 and the formation of an adduct at Ser303 with XCorr score of 3.48 and a probability of 1.1 × 10−4 for the doubly charged modified peptides. The predicted b and y ions of the singly charged modified peptide with the BPA adduct at either Thr302 or Ser303 obtained by using ProteinProspector are shown in Table 2. Modification at Thr302 would yield an ion series in which b6 is 653.3, b7 is 928.3, y6 is 664.4, and y7 is 939.4. For modification at the Ser303, the ion series would be characterized by: b7, 754.3; b8, 1015.4; y5, 577.3; and y6, 838.4. The identity of the modified peptide was further confirmed by MS/MS fragmentation of the doubly charged precursor ion having an m/z 796.8. As shown in Fig. 1, almost all of the expected fragment ions can be identified. In particular, the intensity of the singly charged fragment ions for y7, y8, y9, y10, and y11 and the doubly charged ions for y11, y12, and [MH+2H-2H2O]+2 are very abundant, strongly indicating that the reactive intermediate of BPA with mass shift of 174 Da forms an adduct with either Thr302 or Ser303.

TABLE 2.

Predicted b and y ion series for the modified peptide sequence 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 with MH+ at m/z 1592.5 for adduct formation by BPA at the Thr302 (T*) or Ser303 (Ŝ)

The b and y ion series for the Thr302- or Ser303-modified peptide with an MH+ ion at m/z 1592.5 were calculated from the theoretical b and y ions for the unmodified peptide with the increase of 174 Da by using ProteinProspector software. With the exception of the b7 and y6 ions, the rest of fragment ions for this peptide are the same for the modification site at either Thr302 or Ser303.

| b Ions | Amino Acid Sequence | y Ions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | 148.1 | F | y13 | |

| b2 | 295.1 | F | y12 | 1444.6 |

| b3 | 366.1 | A | y11 | 1297.6 |

| b4 | 423.2 | G | y10 | 1226.5 |

| b5 | 524.3 | T | y9 | 1169.5 |

| b6 | 653.3 | E | y8 | 1068.5 |

| b7 | 928.3* or 754.3^ | T* | y7 | 939.4 |

| b8 | 1015.4 | Ŝ | y6 | 664.4* or 838.4^ |

| b9 | 1102.4 | S | y5 | 577.3 |

| b10 | 1203.5 | T | y4 | 490.3 |

| b11 | 1304.5 | T | y3 | 389.3 |

| b12 | 1417.6 | L | y2 | 288.2 |

| b13 | R | y1 | 175.1 |

For the Thr302-modified peptide, the theoretical ion series at b7 would be 928.3 and y6 would be 664.4.

For the Ser-modified peptide, the theoretical ion series at b7 would be 754.3 and y6 would be 838.4.

Fig. 1.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the modified peptide 296FFAGTETSSTTLR308 with the reactive intermediate formed by BPA adducted to either Thr302 or Ser303. The predicted fragment ion series for the singly charged ion with MH+ at m/z 1592.5 is indicated in Table 2. Data presented are from the MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion with [M+2H]+2 at m/z 796.8 obtained in the positive mode by using Xcalibur software. For modification at Thr302, the ions predicted for b7 and y6 would be 928.3* and 664.4*, respectively. The MS/MS spectrum shown here with the peaks indicated (910.5* for b7-H2O and 664.5* for y6) are consistent with modification at Thr302. For modification of the Ser303, the predicted fragment ions for b7 and y6 would be 754.3∧ and 838.4∧, respectively. However, these two ions are not observed in the MS/MS spectrum.

The identification of fragment ions b7 and y6 in the MS/MS spectrum is the key factor for assigning the actual site for the modification. The observation of the fragment ions at 910.5 and 664.5 is consistent with the theoretical b7-H2O and y6 ions formed by the modification at Thr302 and not at Ser303. For the modification at Ser303, the two predicted fragment ions at 754.3 for b7 and 838.3 for y6 cannot be detected. Although Ser303 has been suggested as a potential site on this peptide for the covalent modification by BPA, MS/MS analysis has revealed that the Thr302 is the predominant site, if not the sole site for the adduct formation, rather than the adjacent Ser303 residue.

MS/MS Analysis of the BPA-Modified 100TIAVIEPIFK109 Peptide.

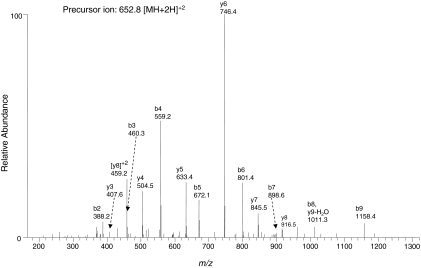

Formation of an adduct of BPA at Thr100 in the peptide sequence 100TIAVIEPIFK109 with a MH+ ion at m/z 1304.7 was also suggested by the SEQUEST search. The search indicated an XCorr score of 2.90 and probability of 8.0 × 10−5 for the doubly charged modified peptide. The identity of the modified peptide was confirmed by MS/MS fragmentation of the doubly charged precursor ion with the m/z 652.8. The b and y ions for the modified peptide were predicted by using ProteinProspector (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 2, almost all of the fragment ions for this modified peptide can be identified, suggesting that Thr100 may also be modified by a reactive metabolite of BPA. However, the relative MS/MS spectral intensities of the major fragment ions for the Thr302-modified peptide are higher than those for the Thr100-modifed peptide and the two search parameters, Xcorr and the probability score, for the Thr302-modified peptide are better than the Thr100-modified peptide. Therefore, on the basis of this proteomics approach, it may be concluded that Thr302 is the primary site and Thr100 is the secondary site in CYP2B1 for covalent modification by BPA.

TABLE 3.

Predicted b and y ion series for the modified peptide sequence 100TIAVIEPIFK109 for adduct formation by of BPA at the Thr100 residue

The b and y ion series for the Thr100-modified peptide with an MH+ ion at m/z 1304.7 were calculated from the theoretical b and y ions for the unmodified peptide with the mass increase of 174 Da on Thr100 by using ProteinProspector software.

| b Ions | Amino Acid Sequence | y Ions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | 276.1 | T | y10 | |

| b2 | 389.1 | I | y9 | 1029.6 |

| b3 | 460.2 | A | y8 | 916.6 |

| b4 | 559.2 | V | y7 | 845.6 |

| b5 | 672.3 | I | y6 | 746.4 |

| b6 | 801.4 | E | y5 | 633.4 |

| b7 | 898.4 | P | y4 | 504.3 |

| b8 | 1011.5 | I | y3 | 407.3 |

| b9 | 1158.6 | S | y2 | 294.2 |

| b10 | K | y1 | 147.1 |

Fig. 2.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the modified peptide 100TIAVIEPIFK109 with the reactive intermediate formed by BPA covalently bound to Thr100. The predicted fragment ion series for the singly charged ion with MH+ at m/z 1304.7 is indicated in Table 3. Data presented are from the MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion with [M+2H]+2 at m/z 652.8 obtained in the positive mode by using Xcalibur software.

Discussion

The results presented here are a follow-up to our previous publication on the inactivation of 2B1 by BPA (Lin et al., 2009). We reported previously that BPA is a very potent mechanism-based inactivator and that the inactivation is caused primarily by covalent modification of the apoprotein. Identification of a BPA-GSH conjugate demonstrated that the mass of the reactive intermediate is 174 Da, corresponding to the mass of BPA plus one oxygen. Deconvolution of the MS spectrum of the modified apoprotein revealed a mass increase equivalent to the addition of one molecule of BPA plus one oxygen atom, indicating that only one residue had been modified per molecule of CYP2B1. Here, we report that the reaction mixtures were digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS followed by a SEQUEST search for an increase in the mass of a tryptic peptide of 174 Da. The search results, summarized in Table 1, suggested that Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 may have been modified by a reactive intermediate of BPA. These three residues all are located in substrate recognition sites (SRSs) in the cytochrome P450 family 2 as proposed by Gotoh (1992). Thr100 is in SRS-1 and located in the B′ helix/loop region. Thr302 and Ser303 are in SRS-4 and located in the I-helix. The MS/MS fragmentation pattern in Fig. 1 clearly shows that formation of an adduct with Thr302 has higher confidence than Ser303 and Thr100. Because Ser303 is adjacent to Thr302, it might be expected that the reactive intermediate of BPA would preferentially bind to Thr302, and Ser303 may not be adducted. However, it is possible that the reactive intermediate may diffuse out to the B′ helix/loop region and react with Thr100.

Two different residues, Tyr75 and Cys239, were recently identified as the sites for covalent modification of the CYP3A4 apoprotein by raloxifene. However, only Tyr75 was identified by Yukinaga et al. (2007), whereas only Cys239 was identified by Baer et al. (2007). The possible reasons for the identification of different sites for adduct formation may include differences in the experimental conditions used for enzymatic digestion and differences in the sequence coverage for P4503A4 (Eggler et al., 2007; Yukinaga et al., 2007). In addition, the Cys98 and Cys468 residues in CYP3A4 both were identified as being covalently modified by lapachenole. However, only one molecule of lapachenole was bound per molecule of protein (Wen et al., 2005). Because we have identified more than one BPA-modified residue for BPA-inactivated CYP2B1, two different residues were identified for raloxifene-inactivated CYP3A4, and two Cys residues in CYP3A4 were covalently modified by lapachenole, it now appears that covalent modification of an apoprotein by a mechanism-based inactivator may not be necessarily limited to one specific residue.

In addition to the results cited in the Introduction, more information on the catalytic role and importance of the conserved Thr residue in the I-helix has been obtained by studies using site-specific mutagenesis of that Thr. Some examples include: 1) studies have demonstrated that Thr302 in CYP2B1 and Thr302 in CYP2B4 are critical determinants for secobarbital and 2EN inactivation, respectively (He et al., 1996; Roberts et al., 1996) and 2) a decrease in the inactivation of 2E1 by 5-phenyl-1-pentyne and several naturally occurring isothiocynates and the reversible formation of a novel heme adduct of tert-butylacetylene were observed in the Thr303A mutant of 2E1 (Roberts et al., 1998; Moreno et al., 2001; Blobaum et al., 2004).

Unlike the early investigations of the amino acid residues in the I-helix, there was relatively little interest in structure–function analysis of the B′ helix/loop region in the CYP2B enzymes until the CYP2B4 crystal structure became available. The crystal structure of CYP2B4 revealed that contacts between residues in the B′ helix and residues in helices G and I play an important role in the opening and closing of the active site of the enzyme (Scott et al., 2004; Zhao and Halpert, 2007). Extensive mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that residues 100–109 (TIAVIEPIFK) in the B′ helix/loop region affect regioselectivity and stereoselectivity of the P450-catalyzed oxidations and substrate entry into the active site of CYP2B1 (Honma et al., 2005). Homology modeling and docking studies have previously revealed that BPA is in close contact with I101 and I104 in CYP2B1 (Lin et al., 2009). In addition, Thr100 is the most nucleophilic residue in this region with the potential to be attacked by a reactive intermediate of BPA. The formation of an adduct of BPA at Thr100 might be expected to alter substrate binding and subsequent catalysis.

Halpert and co-workers have used site-directed mutagenesis to investigate the functional roles of Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 in the metabolism of testosterone and androstenedione (He et al., 1994; Honma et al., 2005). Their results indicate that: 1) mutagenesis of Thr302 resulted in a 5-fold larger decrease in 16β-hydroxylase activity for testosterone compared with 16α-hydroxylase activity, whereas 16α-hydroxylase and 16β-hydroxylase activities for androstenedione decreased in parallel, 2) mutagenesis of the Ser303 residue did not result in any significant alterations in testosterone or androstenedione metabolism, and 3) mutation of the Thr100 residue resulted in a 2-fold decrease in 16α-hydroxylation activity for testosterone, whereas 16β-hydroxylation activity decreased to a lesser extent. These site-directed mutagenesis studies suggested that Thr302 and Thr100, but not Ser303, may be in close proximity to P450-bound testosterone and play a critical role in the stereoselectivity for testosterone metabolism.

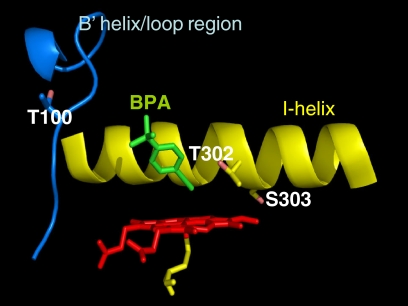

In the attempt to better understand our experimental results, BPA was docked into a model for the CYP2B1 active site that was constructed based on the crystal structure of CYP2B4 (Scott et al., 2004). Using this model, the orientations of BPA with respect to Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 residues in the CYP2B1 structure were investigated. As shown in Fig. 3, the triple bond of BPA is positioned within the active site at a distance of approximately 2.96 Å from the heme iron. The shortest distances from BPA and the heme iron to the Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 residues have been calculated and are shown in Table 4. As can be seen, the Thr302 residue is in close contact with the ethynyl moiety of BPA with the distance being 3.42 Å. In contrast, Ser303 is pointed away from the active site cavity and thus would not be expected to interact with substrate. Compared with Thr302, Thr100 is relatively far from the heme iron and BPA, suggesting that adduct formation at Thr302 would be favored. In short, our homology modeling and docking analyses are consistent with previous site-directed mutagenesis studies (He et al., 1994; Honma et al., 2005). Thus, Thr302 is the primary site for adduct formation resulting in the inactivation of CYP2B1 by BPA.

Fig. 3.

Results of homology modeling and docking studies for the binding of BPA into the CYP2B1 active site. Partial structures from the homology model are shown with the locations of Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 indicated with respect to the heme and BPA. BPA was docked into the active site as described under Materials and Methods. The ethynyl moiety of BPA faces the heme iron. Shown are the I-helix (yellow ribbon), the B′ helix/loop region (blue), the Thr100, Thr302, and Ser303 residues (white), BPA (green), the heme (red), and the axial Cys436 (yellow stick).

TABLE 4.

Results from homology modeling and substrate docking in the CYP2B1 active site

The CYP2B1 homology model was constructed based on the CYP2B4 crystal structure, and BPA was docked into active site as described under Materials and Methods.

| Residue Modified | Location | Distance to the Heme Irona | Distance to BPAa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Å | |||

| Thr100 | B′helix/loop | 15.44 | 8.31 |

| Thr302 | I-helix | 6.22 | 3.42 |

| Ser303 | I-helix | 8.57 | 7.67 |

Distance between the nearest atom of each amino acid residue and the heme iron or BPA in the CYP2B1 homology model calculated by using PyMOL.

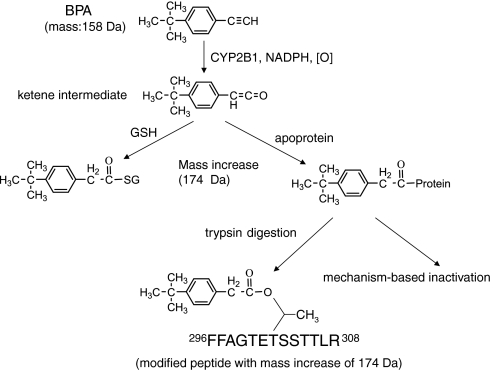

The trapping and elucidation of the structures of GSH conjugates of mechanism-based inactivators are widely used to determine the identity of the reactive metabolites when probing the mechanism of inactivation. The structure of the reactive intermediate of the compound that forms a GSH conjugate is generally believed to be the same as that that reacts with nucleophilic residues in the active site of the protein leading to covalent modification and inactivation. The pathways proposed for the formation of a reactive intermediate of BPA and the formation of a protein-bound adduct during the mechanism-based inactivation of CYP2B1 by BPA are illustrated in Fig. 4. The ketene intermediate derived from oxidation of the acetylene by CYP2B1 may be oriented in the active site in such a way that nucleophilic attack by the hydroxyl group of Thr to form an ester linkage in the apoprotein adduct is facilitated. In conclusion, Thr302 has been identified as the principal site of BPA adduct formation in CYP2B1 leading to mechanism-based inactivation. Recently, our laboratory has reported that BPA is bound to Thr302 in CYP2B4 and inactivates the enzyme by causing steric hindrance (Zhang et al., 2009). Mutagenesis studies of Thr100 and Thr302 to Val are underway to elucidate the involvement of the residues in the mechanism-based inactivation of CYP2B1 by BPA.

Fig. 4.

Pathways proposed for the covalent modification of CYP2B1 by a reactive intermediate of BPA. The formation of the GSH conjugate, covalent binding of the reactive intermediate to the apoprotein, and the modified peptides are discussed in the text.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kathleen Noon (Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Facility, Department of Pharmacology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI) for performing capillary LC-MS/MS analyses and Dr. Anastasia Yocum (Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School) for valuable discussions and contributions to the SEQUEST database searches and analyses.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [Grant CA-16954].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.109.164350.

- CYP2B1

- cytochrome P450 2B1

- BPA

- 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene

- GSH

- glutathione

- TFA

- trifluoroacetic acid

- HPLC

- high-pressure liquid chromatography

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- LC-MS/MS

- liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- SRS

- substrate recognition site

- 2EN

- 2-ethynylnaphthalene

- 9EP

- 9-ethynylphenanthrene

- XCorr

- cross-correlation.

References

- Baer et al., 2007.Baer BR, Wienkers LC, Rock DA. (2007) Time-dependent inactivation of P450 3A4 by raloxifene: identification of Cys239 as the site of apoprotein alkylation. Chem Res Toxicol 20:954–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobaum et al., 2002.Blobaum AL, Kent UM, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (2002) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 2E1 and 2E1 T303A by tert-butyl acetylenes: characterization of reactive intermediate adducts to the heme and apoprotein. Chem Res Toxicol 15:1561–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobaum et al., 2004.Blobaum AL, Kent UM, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (2004) Novel reversible inactivation of cytochrome P450 2E1 T303A by tert-butyl acetylene: the role of threonine 303 in proton delivery to the active site of cytochrome P450 2E1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggler et al., 2007.Eggler AL, Luo Y, van Breemen RB, Mesecar AD. (2007) Identification of the highly reactive cysteine 151 in the chemopreventive agent-sensor Keap 1 protein is method-dependent. Chem Res Toxicol 20:1878–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroozesh et al., 1997.Foroozesh M, Primrose G, Guo Z, Bell LC, Alworth WL, Guengerich FP. (1997) Aryl acetylenes as mechanism-based inhibitors of cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol 10:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda et al., 1993.Fukuda T, Imai Y, Komori M, Nakamura M, Kusunose E, Satouchi K, Kusunose M. (1993) Replacement of Thr-303 of P450 2E1 with serine modifies the regioselectivity of its fatty acid hydroxylase activity. J Biochem 113:7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh, 1992.Gotoh O. (1992) Substrate recognition sites in cytochrome P450 family 2 (CYP2) proteins inferred from comparative analyses of amino acid and coding nucleotide sequences. J Biol Chem 267:83–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanioka et al., 1992.Hanioka N, Gonzalez FJ, Lindberg NA, Liu G, Gelboin HV, Korzekwa KR. (1992) Site-directed mutagenesis of cytochrome P450s CYP2A1 and CYP2A2: influence of the distal helix on the kinetics of testosterone hydroxylation. Biochemistry 31:3364–3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasemann et al., 1995.Hasemann CA, Kurumbail RG, Boddupalli SS, Peterson JA, Deisenhofer J. (1995) Structure and function of cytochrome P450: a comparative analysis of three crystal structures. Structure 2:41–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al., 1994.He Y, Luo Z, Klekotka PA, Burnett VL, Halpert JR. (1994) Structural determinants of cytochrome P450 2B1 specificity: evidence for five substrate recognition sites. Biochemistry 33:4419–4424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al., 1996.He K, He YA, Szklarz GD, Halpert JR, Correia MA. (1996) Secobarbital-mediated inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 and its active site mutants. Partitioning between heme and protein alkylation and epoxidation. J Biol Chem 271:25864–25872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma et al., 2005.Honma W, Li W, Liu H, Scott EE, Halpert JR. (2005) Functional role of residues in the helix B′ region of cytochrome P450 2B1. Arch Biochem Biophys 435:157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai and Nakamura, 1988.Imai Y, Nakamura M. (1988) The importance of threonine-301 from cytochromes P-450 [laurate (ω-1)-hydroxylase and testosterone 16α-hydroxylase] in substrate binding as demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS Lett 234:313–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent et al., 2002.Kent UM, Mills DE, Rajnarayanan RV, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (2002) Effect of 17α-ethynylestradiol on activities of cytochrome P450 2B (P4502B) enzymes: characterization of inactivation of P450s 2B1 and 2B6 and identification of metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent et al., 2008.Kent UM, Sridar C, Spahlinger G, Hollenberg PF. (2008) Modification of serine 360 by a reactive intermediate of 17-α-ethynylestradiol results in mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 and 2B6. Chem Res Toxicol 21:1956–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al., 2002.Lin HL, Kent UM, Hollenberg PF. (2002) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 3A4 by 17α-ethynylestradiol: evidence for heme destruction and covalent binding to protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301:160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al., 2003.Lin HL, Zhang H, Waskell L, Hollenberg PF. (2003) Threonine-205 in the F helix of p450 2B1 contributes to androgen 16β-hydroxylation activity and mechanism-based inactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306:744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al., 2009.Lin HL, Zhang H, Noon KR, Hollenberg PF. (2009) Mechanism-based inactivation of CYP2B1 and its F-helix mutant by two tert-butyl acetylenic compounds: covalent modification of prosthetic heme versus apoprotein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:392–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno et al., 2001.Moreno RL, Goosen T, Kent UM, Chung FL, Hollenberg PF. (2001) Differential effects of naturally occurring isothiocynates on the activities of cytochrome P450 2E1 and the mutant P450 2E1 T303A. Arch Biochem Biophys 391:99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris et al., 1996.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Huey R, Olson AJ. (1996) Distributed automated docking of flexible ligands to proteins: parallel applications of AutoDock 2.4. J Comput Aided Mol Des 10:293–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano and Kunze, 1981.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Kunze KL. (1981) Shift of the acetylenic hydrogen during chemical and enzymatic oxidation of the biphenylacetylene triple bond. Arch Biochem Biophys 209:710–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano and Komives, 1985.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Komives EA. (1985) Branchpoint for heme alkylation and metabolite formation in the oxidation of arylacetylenes by cytochrome P450. J Biol Chem 260:3330–3336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos, 1991.Poulos TL. (1991) Modeling of mammalian P450s on basis of P450cam X-ray structure. Methods Enzymol 206:11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raag et al., 1991.Raag R, Martinis SA, Sligar SG, Poulos TL. (1991) Crystal structure of the cytochrome P-450cam active site mutant Thr252Ala. Biochemistry 30:11420–11429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran et al., 1993.Ravichandran KG, Boddupalli SS, Hasemann CA, Peterson JA, Deisenhofer J. (1993) Crystal structure of hemoprotein domain of P450BM-3, a prototype for microsomal P450s. Science 276:731–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 1993.Roberts ES, Hopkins NE, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (1993) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 by 2-ethnylnaphthalene: identification of an active-site peptide. Chem Res Toxicol 6:470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 1994.Roberts ES, Hopkins NE, Zaluzec EJ, Gage DA, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (1994) Identification of active-site peptides from 3H-labeled 2-ethynylnaphthalene-inactivated P450 2B1 and 2B4 using amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 33:3766–3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 1995.Roberts ES, Hopkins NE, Zaluzec EJ, Gage DA, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (1995) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B1 by 9-ethynylphenanthrene. Arch Biochem Biophys 323:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 1996.Roberts ES, Pernecky SJ, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (1996) A role of threonine 302 in the mechanism-based inactivation of P450 2B4 by 2-ethynylnaphthalene. Arch Biochem Biophys 331:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 1998.Roberts ES, Alworth WL, Hollenberg PF. (1998) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochromes P450 2E1 and 2B1 by 5-phenyl-1-pentyne. Arch Biochem Biophys 354:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott et al., 2004.Scott EE, White MA, He YA, Johnson EF, Stout CD, Halpert JR. (2004) Structure of mammalian cytochrome 2B4 complexed with 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole at 1.9-Å resolution: insight into the range of P450 conformations and the coordination of redox partner binding. J Biol Chem 279:27294–27301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen et al., 2005.Wen B, Doneanu CE, Gartner CA, Roberts AG, Atkins WM, Nelson SD. (2005) Fluorescent photoaffinity labeling of cytochrome P450 3A4 by lapachenole: identification of modification sites by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 44:1833–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukinaga et al., 2007.Yukinaga H, Takami T, Shioyama SH, Tozuka Z, Masumoto H, Okazaki O, Sudo K. (2007) Identification of cytochrome P450 3A4 modification site with reactive metabolite using linear ion trap-Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol 20:1373–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al., 2009.Zhang H, Lin HL, Walker VJ, Hamdane D, Hollenberg PF. (2009) tert-Butylphenylacetylene is a potent mechanism-based inactivator of cytochrome P450 2B4: inhibition of cytochrome P450 catalysis by steric hindrance. Mol Pharmacol 76:1011–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao and Halpert, 2007.Zhao Y, Halpert JR. (2007) Structure–function analysis of cytochrome P450 2B. Biochim Biophy Acta 1770:402–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]