Abstract

The mechanical landscape in biological systems can be complex and dynamic, with contrasting sustained and fluctuating loads regularly superposed within the same tissue. How resident cells discriminate between these scenarios to respond accordingly remains largely unknown. Here, we show that a step increase in compressive stress of physiological magnitude shrinks the lateral intercellular space between bronchial epithelial cells, but does so with strikingly slow exponential kinetics (time constant ∼110 s). We confirm that epidermal growth factor (EGF)-family ligands are constitutively shed into the intercellular space and demonstrate that a step increase in compressive stress enhances EGF receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation with magnitude and onset kinetics closely matching those predicted by constant-rate ligand shedding in a slowly shrinking intercellular geometry. Despite the modest degree and slow nature of EGFR activation evoked by compressive stress, we find that the majority of transcriptomic responses to sustained mechanical loading require ongoing activity of this autocrine loop, indicating a dominant role for mechanotransduction through autocrine EGFR signaling in this context. A slow deformation response to a step increase in loading, accompanied by synchronous increases in ligand concentration and EGFR activation, provides one means for cells to mount a selective and context-appropriate response to a sustained change in mechanical environment.—Kojic, N., Chung, E., Kho, A. T., Park, J.-A., Huang, A., So, P. T. C., Tschumperlin, D. J. An EGFR autocrine loop encodes a slow-reacting but dominant mode of mechanotransduction in a polarized epithelium.

Keywords: airway epithelium, mechanical stress, lateral intercellular space

Our understanding of how cells convert cues from the mechanical environment into biochemical signals is expanding rapidly as the molecular details of mechanotransduction processes emerge (1,2,3,4). In most cases, cellular responses to changes in mechanical status are initiated within seconds (1, 5,6,7). Such rapid mechanotransduction kinetics enable prompt cellular responses to acute changes in mechanical environment. We have far less understanding of how cells, in the context of dynamic mechanical environments present in vivo, discriminate between different mechanical scenarios that require distinct responses. For instance, in the lung, every breath generates transient fluctuations in stress and strain (8), whereas more sustained changes in stress and strain occur with bronchoconstriction and during morphogenesis and growth (9). Similarly, cells of the cardiovascular system regularly undergo pulsatile changes in loading (pressure and shear stress) but can also experience sustained changes in blood pressure in disease conditions such as chronic hypertension (10, 11). While rapid mechanoresponse mechanisms appear well suited for transducing transient or fluctuating loads, it remains unclear how cells mount selective and context-appropriate responses to sustained loads, while effectively filtering out transient mechanical perturbations.

In previous work, we observed that bronchial epithelial cells respond to sustained compressive stress (a transcellular apical to basal pressure gradient) with enhanced activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), accompanied by a dramatic reduction in the volume of the lateral intercellular space (LIS) separating neighboring cells (12). Prior studies (13,14,15,16,17), and our own observations (12), indicated that the EGFR is localized along the basolateral surfaces of bronchial epithelial cells, effectively lining the boundaries of the LIS. We thus proposed that compressive stress could activate the EGFR through the action of constitutive autocrine signaling in a shrinking lateral intercellular space (12). Until now, however, imaging limitations have prevented us from directly comparing the kinetics of LIS deformation with the temporal pattern of EGFR activation. Such a side-by-side comparison of deformation and signaling is vitally important to test the underlying validity of the proposed mechanotransduction mechanism.

In this study, we employ high-speed 2-photon microscopy to overcome prior imaging limitations, allowing us for the first time to characterize the kinetics of LIS deformations in response to step increases in loading. By combining the resulting measures of compression-induced LIS deformations with a computational diffusion-convection model of constitutive ligand shedding, we directly compare predicted changes in interstitial ligand concentrations with the experimentally measured EGFR response to compressive stress. We show that the slow physical deformation of the LIS in response to a step increase in loading leads to synchronous activation of the EGFR; this response is found only in the context of sustained mechanical stress and not in response to transient loads similar in duration to spontaneous or deep inspirations, demonstrating a selective mechanotransduction response tuned to sustained loading. Finally, to investigate the biological relevance of EGFR-mediated mechanosignaling, we measure transcriptomic responses to sustained loading in the presence and absence of a small-molecule inhibitor of EGFR activity. Our findings demonstrate that extracellular autocrine mechanotransduction is an important regulator of mechanical signaling in this context, and they establish a novel mechanism by which cells can mount selective responses to a sustained change in their mechanical environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells were obtained from a commercial source (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) and cultured at an air-liquid interface, as described previously (18). Briefly, cells were expanded on tissue culture-treated plastic (5% CO2, 37°C) in bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM, Clonetics, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with BSA (1.5 μg/ml) and retinoic acid (50 nM). Passage 3 cells were plated onto uncoated nucleopore membranes (0.4-μm pore size; Transwell Clear, Costar, Bethesda, MD, USA) at 100,000 cells/well (∼20,000 cells/cm2). The cells were fed with a 1:1 mixture of BEGM and DMEM (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) applied every 2 d both apically and basally until confluent, then basally after an air-liquid interface was established.

Shedding analysis

ELISAs for EGF and TGF-α were used as recommended by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). A neutralizing EGFR antibody (clone 225; Lab Vision, Fremont, CA, USA) was used to block ligand-receptor interactions. For HB-EGF, an ELISA was developed based on published methods (19). Briefly, 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Nunc MaxiSorp; Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) were incubated with polyclonal goat anti-human HB-EGF antibody (1 μg/ml; R&D Systems) at room temperature for 8 h. Plates were then blocked overnight at 4°C with blocking buffer [Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 3.5% BSA]. After washing with TBS plus 0.05% Tween (TBST), recombinant protein standards (R&D Systems) and medium samples were added to wells and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Following repeated washing with TBST, biotinylated antibody (0.5 μg/ml polyclonal goat anti-human; R&D Systems) against the relevant ligand was added to each well for 1.5 h at room temperature. After another series of washes, wells were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After a final series of washes, sequential incubation with substrate, amplifier, and stop solution (Invitrogen ELISA Amplification Kit) was followed by colorimetric measurement and analysis (Bio-Rad Model 680, Microplate Manager 5.2; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

EGFR phosphorylation analysis

Cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 200 μl of Cell Extraction Buffer (Biosource) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors as recommended by the manufacturer. Crude cell extracts were collected by scraping and incubated on ice for 30 min with vortexing at 10-min intervals. Samples were centrifuged at 11,000 g for 10 min, and supernatants were diluted 1:10 or 1:50 and assayed for phospho-EGFR (tyrosine 1068) or total EGFR by ELISA (Biosource) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance data were collected and analyzed against serial dilutions of positive control standard to compute the concentration of phospho-EGFR and EGFR.

Application of mechanical stress

To simulate the mechanical stress experienced by the airway epithelium during bronchoconstriction, a silicon plug with an access port for pressure application was press fitted into the top of each transwell, creating a sealed pressure chamber over the apical surface of the NHBE cells. Each plug was connected to a 5% CO2 (balance room air) pressure cylinder, with pressure level maintained by regulator and monitored by manometer. The pressure in the apical chamber was increased to the desired pressure (10, 30, or 50 cmH2O), while the basal surface and medium remained at atmospheric pressure. The resulting apical-to-basal transcellular pressures produced continuous compressive stresses comparable to those present in the airway epithelium during bronchoconstriction (20,21,22), an order of magnitude higher than the stress experienced by the airway epithelium during breathing (9).

Image acquisition and analysis

A custom-built high-speed 2-photon microscope was used to view live NHBE cells in transwells inverted such that the upright microscope objective was immersed in the basal medium (23). A pressure source was connected to the otherwise sealed apical chamber of the cells to apply the apical to basal transcellular pressure. All of the experiments were performed at room temperature, and the pressure source supplied compressed air containing 5% CO2. To mark the extracellular space, a high-molecular-mass fluorescent FITC-dextran (either 70 or 150 kDa) was used.

Images were acquired at 10 frames/s. The field of view was 300 × 400 pixels, which for an ×63 objective (Achroplan, ×63/0.9 W; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) translated into image dimensions of 80 × 95 μm. A stack of 30 planar images separated by a distance of 1 μm could be acquired in ∼3 s with this configuration. Images were segmented into cellular and LIS fractions using a custom-weighted directional adaptive-thresholding (23) method. By summing all of the LIS pixels for each stack of images, the total LIS volume for every time point was calculated. LIS volume changes were normalized with respect to the initial, prepressure volume for each experiment.

Computational modeling

Ligand diffusion-convection in the LIS was modeled as previously detailed (24). Briefly, the epithelial interstitial space was divided into 3 domains: LIS, transitional, and radial. The transitional domain was included to avoid numerical difficulties that can occur when transitioning from the 1-D cartesian coordinate system of the LIS to the cylindrical coordinates of the underlying reservoir (radial domain). The space and time-varying ligand concentration C(w, x, t) was computed as a function of LIS width, with w(t) obtained from the imaging experiments described above. The diffusion-convection equations, along with the boundary conditions of no flux at the most apical point (impermeable tight junction) and 0 concentration distant from the LIS were solved for the ligand concentration (as a function of both time and space) using the PAK finite element method software package. The spatially varying ligand concentration was then expressed as a mean (or average) LIS concentration at a given time:

|

where h is the LIS height (see Fig. 4C and Supplemental Fig. S2).

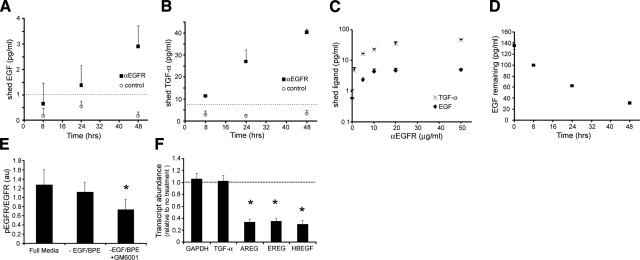

Figure 1.

Constitutive ligand shedding and autocrine EGFR activity. A, B) Time-dependent accumulation of EGF (A) and TGF-α (B)in basal medium of ALI-cultured NHBE cells in the absence (control) and presence of an EGFR neutralizing antibody (αEGFR; 20 μg/ml). Dashed lines indicate ELISA sensitivities. C) Dose-response effect of EGFR-neutralizing antibody on EGF and TGF-α accumulation over 48 h, demonstrating plateau at 20 μg/ml. D) Time-dependent loss of exogenous EGF added to basal medium of NHBE cells without EGFR antibody. E) Omission of EGF/BPE from full-growth medium does not significantly decrease baseline levels of phosphorylated (active) fraction of EGFR. However, addition of the MMP inhibitor GM6001 (10 μM) for 1 h significantly reduces phosphoEGFR (tyr 1068; P=0.005) relative to full growth medium condition. F) Addition of AG1478 (1 μM), an EGFR-kinase inhibitor, for 2 h selectively attenuates expression of genes encoding EGF-family ligands AREG (P=0.013), EREG (P=0.011), and HBEGF (P=0.006), but not TGF-α, relative to GAPDH expression. Data are means ± sd from 3 or 4 wells from one of ≥2 replicate experiments. *P ≤ 0.05.

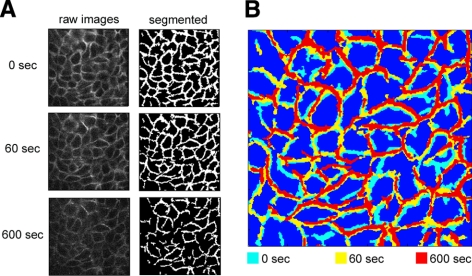

Figure 2.

Visualizing intercellular deformations under sustained compressive stress. A) Comparison of raw and segmented images for matched optical sections at 0, 60, and 600 s after onset of continuous transcellular pressure (30 cmH2O). B) Composite image shows comparative LIS geometry at 0, 60, and 600 s after onset of continuous pressure gradient. Note that the NHBE cells form a 3-dimensional structure; hence, out-of-plane motions affect the degree to which the optical sections are superimposed.

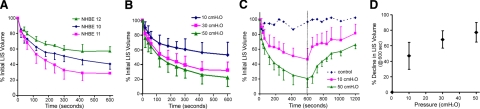

Figure 3.

Mechanical characterization of LIS deformations. A) Time-dependent changes in LIS volume (normalized to time 0) for 3 cell donors over 600 s of 30 cmH2O continuous compressive stress. Best-fit exponentials for each donor yielded time constants of 100, 116, and 113 s for donors 10, 11 and 12, respectively. B) Comparison of time-dependent LIS volume changes in NHBE 11 cells under 10, 30, and 50 cmH2O continuous compressive stress. Best-fit exponentials yielded time constants of 100, 109, and 114 s for the 10, 30, and 50 cmH2O pressure loads, respectively. C) LIS volume changes during and after continuous compressive stress for 600 s; NHBE 11 cells at 10 and 50 cmH2O, as well as time-matched control. Vertical dashed line indicates time at which applied compressive stress was removed (600 s). Best-fit exponential time constants during the loading phase were 111 and 116 s, and during the recovery phase 154 and 312 s for 10 and 50 cmH2O loads, respectively. D) Change in LIS volume at 600 s vs. applied pressure gradient for donor 11. Data are means ± sd from 3–4 independent replicate experiments.

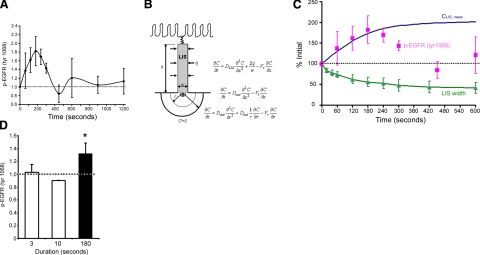

Figure 4.

Comparing kinetics of ligand accumulation and EGFR activation. A) Time-dependent changes in phospho-EGFR (tyr 1068) during continuous compressive stress (30 cmH2O). Phospho-EGFR results were normalized to time 0 controls within each experiment and expressed as means ± sd, n = 4 experiments. B) Schematic of the LIS and the governing ligand diffusion-convection equations used to compute spatial and temporal changes in LIS ligand concentration C(t) that occur with changes in LIS width w(t). C) Comparison of temporal (normalized to time 0) changes in LIS width (means±sd from 3 cell donors in Fig. 3A), calculated ligand concentration [CLIS, mean is C(t) averaged over LIS height], and measured phospho-EGFR from A. D) Phospho-EGFR levels at 180 s after exposure to compressive stress (30 cmH2O) for 3, 10, or 180 s, using an independent donor from experiments in A and C. Data are means ± sd from 3, 2, and 5 experiments, respectively for 3, 10, and 180 s conditions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was purified from cell lysates (RNeasy; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Equal amounts of RNA (2 μg) were reverse transcribed using MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) by incubation at 42°C for 30 min. Real-time PCR reactions were performed using 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad). Fold changes were calculated using the ΔΔCt method (25). Real Time PCR primers (Invitrogen) targeting ATF3, CCND1, CHI3L1, CYR61, DUSP5, DUSP6, ELF4, ELK1, FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, HOXB7, KLF2, PIAS1, PLAU, PLAUR, RAP1GAP, SPRED2, TNK1, and TRIB3, (see Supplemental Data for primer sequences) and HBEGF, EREG, AREG, TGF-α, and GAPDH (see ref. 26 for sequences) were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) with similar melting point temperatures, primer lengths, and amplicon lengths in order to obtain similar PCR efficiency. Each primer was tested against GAPDH over a range of concentrations to ensure similar PCR efficiency.

Microarray analysis

NHBE cells were studied under 4 different conditions: control (C), pressure 30 cmH2O (P), AG1478 (1 μM, A), and pressure plus AG1478 (P+A) at 1, 3, and 8 h, all in the absence of exogenous EGF. Samples were also collected at time 0 for control and AG1478 conditions (AG1478 was added 60 min prior to experiment). Each experiment was performed 4 times, with total RNA purified from cell lysates (RNeasy; Qiagen), and equal mass quantities from each replicate experiment combined into a single pooled sample for microarray analysis. Whole-transcriptome profiling was performed using the Affymetrix HG-U133A microarray, which contains 22,283 probes representing 12,863 unique Entrez-identified genes. The data set was normalized by standard robust multiple-array average (RMA) background correction (27), and the resulting probe signals were represented in natural logarithmic scale. For each probe, we considered its signal fold change (difference in logarithmic scale, AvgLF) between C and P, and between A and P + A. To estimate the technical variation of probe signals, we assumed that in the ideal case, the gene signals should be time invariant in C conditions. Thus, any signal variation observed for a gene in C conditions may be attributed to technical noise (NoisLF). NoisLF is calculated as the difference between averages of the 2 largest and 2 smallest signals in conditions C0–8 (28, 29). Since there are no replicate microarray measurements, the AvgLF for a probe was classified as pressure dependent if its P/C magnitude was ≥0.5210 log fold (1.68 linear fold change) and exceeded its NoisLF value. The selection of 0.5210 log fold as a threshold was motivated by previous evidence that HBEGF is reproducibly pressure dependent (26, 30). The AvgLF of the two HBEGF probes on the microarray were probe 38037_at, AvgLF P1/C1 0.4471, AvgLF P+A1/A1 0.0626, NoisLF 0.3363, and probe 203821_at, AvgLF P1/C1 0.5210, AvgLF P+A1/A1 −0.1085, NoisLF 0.4169. We thus selected the more responsive of the HBEGF probes to provide a rational threshold for pressure responsiveness.

Gene ontology enrichment assessment was performed using DAVID 2008 online database version February 2009 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) (31). Fisher exact test was used to assess the proportional significance of genes from a particular ontologic category in a given list of unique genes, relative to the background of 12,863 unique Entrez-identified genes on the HG-U133A microarray platform (32). In addition, an odds ratio (fold enrichment) was used to measure the strength of overrepresentation for the particular ontologic category.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± sd, and where indicated, were analyzed by 2-tailed Student’s t test (values of P<0.05 considered significant), with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Constitutive autocrine EGFR activity

EGF-family ligands are synthesized as membrane-spanning propeptides and are proteolytically shed from the cell surface to release mature growth factor (33). One premise on which the previously proposed autocrine mechanotransduction mechanism is based (12)—constitutively active autocrine signaling localized to the LIS of highly confluent and differentiated epithelia—has not been unequivocally tested. To evaluate whether constitutive shedding and receptor binding of EGF-family ligands is present under baseline conditions in NHBE cells, we pursued two parallel approaches: direct measurement of spontaneous ligand shedding by cells, and assessment of changes in EGFR phosphorylation and downstream gene expression under conditions that would interrupt the putative autocrine loop.

To measure ligand shedding, we employed commercially available ELISAs for TGF-α and EGF, two of the major ligands of the EGF family (33). Because previous results highlighted a role for HB-EGF in mechanotransduction (30), we also developed an ELISA for HB-EGF (adapted from (19), and verified that it displayed sensitivity similar to that of the commercially available TGF-α kit. We grew NHBE cells on microporous substrates at air-liquid interface using defined growth medium to generate pseudostratified epithelial cultures displaying a mucociliary phenotype (18). To measure spontaneous shedding of ligands, we fed the cells with fresh medium, omitting EGF and bovine pituitary extract (BPE; which may itself contain trace amounts of EGF-family ligands), and collected basal conditioned medium at 8, 24, and 48 h. During 48 h of incubation, the cells appeared normal under these culture conditions, but levels of EGF and TGF-α in the medium did not reach the minimum levels measurable by ELISA (Fig. 1A, B). We confirmed this result for TGF-α in the presence of normal growth medium (including EGF and BPE; data not shown).

Because cultured NHBE cells express abundant EGFR (12, 17), we reasoned that ligand production could be masked by efficient receptor-mediated capture (34,35,36). To reveal this cryptic ligand shedding activity, we incubated cells with a neutralizing EGFR antibody that prevents ligand-receptor interactions; its effect on ligand accumulation reached a plateau at concentrations ≥20 μg/ml (Fig. 1C). In the presence of neutralizing EGFR antibody, both EGF and TGF-α accumulated to measurable levels in the basal medium over 48 h (Fig. 1A, B), with TGF-α accumulating at a >20-fold higher rate than EGF (∼24 vs. ∼1 molecule/cell/h, respectively). Notably, ligand accumulation under these conditions occurred at an approximately constant rate, consistent with a constitutive ligand shedding process. Shedding of TGF-α was not altered by inclusion of EGF in the growth medium, nor was it significantly altered by application of continuous compressive stress for 8 h (not shown), further supporting a robust constitutive shedding process. When cells were fed with normal EGF-containing growth medium, EGF levels decreased at a rate of ∼26 molecules/cell/h (Fig. 1D), comparable to the measured rates of spontaneous constitutive shedding of TGF-α, again consistent with the capacity of cells to efficiently capture EGF-family ligands. Together, these results demonstrate the presence of constitutive ligand shedding in NHBE cells, and emphasize that these cells are extremely efficient in capturing endogenous shed ligands in a local autocrine circuit (34).

Unlike the case for EGF and TGF-α, we were unable to measure HB-EGF accumulation in medium under any circumstance, which is surprising given that we had previously demonstrated its surface expression by immunohistochemistry under identical culture conditions (30). Subsequent experiments (see below) demonstrated that blocking EGFR suppresses baseline HBEGF gene expression, but not TGF-α, transcript levels; hence, the absence of measured HB-EGF shedding in the presence of EGFR-neutralizing antibody is likely an unintended consequence of the EGFR blockade on HBEGF transcription and subsequent HB-EGF synthesis. Additional mechanisms also likely conspire against accumulation of measurable HB-EGF in the basolateral media, including the higher molecular mass and more abundant glycosylation of HB-EGF than either TGF-α or EGF (24, 33, 37), as well as the potential for HB-EGF to bind to other cell surface proteins, such as ErbB4 (37).

To assess the consequences of perturbing the putative EGFR autocrine loop, we measured spontaneous EGFR phosphorylation levels (tyrosine residue 1068) in cultured NHBE cells by phospho-specific ELISA. Phosphorylation of EGFR on tyrosine 1068 is directly implicated in downstream signaling through Ras/MAP kinase signaling pathway (38). As expected, cells in standard growth medium (with EGF and BPE) exhibited low but measurable levels of EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 1E). Incubation of cells for 24 h in the absence of exogenous EGF and BPE slightly reduced phospho-EGFR levels, but the effect did not reach statistical significance. The addition of a broad-spectrum metalloprotease inhibitor (GM 6001) for 1 h significantly reduced phospho-EGFR levels relative to both control and EGF/BPE-free medium. These results indicate that a significant fraction of baseline EGFR activity depends on metalloprotease activity, consistent with constitutive proteolytic shedding of EGF-family ligands.

To establish a functional role for constitutive EGFR activity, we evaluated transcript levels for several genes in the presence and absence of an EGFR-specific kinase inhibitor (AG1478, 1μM) by quantitative real-time PCR. While AG1478 had no effect on GAPDH and TGF-α transcript levels, under otherwise normal culture conditions, it significantly reduced transcript levels for EGF-family ligands amphiregulin (AREG), epiregulin (EREG), and HBEGF (Fig. 1F). Our results confirm that baseline EGFR activity is functionally relevant in the context of steady-state expression of select genes (35). Moreover, our findings emphasize that expression of a subset of EGF-family transcripts is dependent on baseline EGFR activity (26), emphasizing a potential confounding effect of receptor blocking strategies on spontaneous ligand shedding measurements. TGF-α transcript levels, however, were unaffected by EGFR inhibition, underscoring the soundness of our approach to measuring TGF-α shedding (Fig. 1B).

Kinetics of LIS deformation

While we previously showed that compressive stress dramatically shrinks the lateral intercellular space separating neighboring epithelial cells (12), imaging limitations prevented us from assessing the kinetics of this process. We therefore modified our 2-photon microscopy approach to improve temporal resolution (23). The enhanced image acquisition method allowed us to capture stacks of images at 1-μm intervals, spanning the entire epithelial depth within ∼3 s. We exposed NHBE cells to a step increase in compressive stress of 30 cmH2O (12), and collected stacks of images throughout the epithelial cell layer prior to and at various intervals during 10 min of continuous compressive stress (Fig. 2A). The lateral intercellular space was visualized by imaging 150-kDa fluorescent FITC-dextran added to the basal surface several minutes prior to mechanical loading to allow diffusion and even distribution throughout the LIS. Images were analyzed with a custom-weighted directional adaptive-threshold method to segment the LIS (23). The parameters of the thresholding method were calibrated using a preliminary set of images, and then applied uniformly to all subsequent analyses. Time-matched control experiments confirmed minimal fluctuations in FITC-dextran defined LIS geometry in the absence of pressure application.

Superimposing LIS segmentation images from 0, 60, and 600 s (Fig. 2B) illustrated the gradual nature, and relatively homogenous distribution of changes in interstitial spacing that occurred under loading, particularly within the first 60 s. When the volume history of the LIS under loading was reconstructed from three different cell donors, we observed reproducible kinetics and magnitudes of LIS volume changes within donor replicates, and reproducible differences in the magnitudes of volume changes across donors (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, the kinetics of LIS volume change for each donor fit exponential relationships with time constants in a narrow range of 110–116 s. How can we account for such slow deformation responses to a step increase in loading? The most obvious explanation is that the kinetics of deformation are dominated by resistance to fluid flow through the LIS and underlying porous substrate. However, a simple calculation assuming Poiseuille tube flow revealed that the entire contents of the LIS could be emptied through the substrate pores in <1 s under the imposed pressure gradient if the only factor retarding LIS deformation was substrate flow resistance. Similarly, the coupled flow resistance of the substrate pores and the LIS channels themselves would still allow the LIS to be emptied in <3 s (see Supplemental Data, Tube Flow Analysis). Clearly then, it is not simple tube flow resistance that dominates the kinetics of LIS volume changes. In contrast to the changes in LIS volume, we did not observe any changes in cellular volume (Supplemental Fig. S1).

To more fully characterize the LIS mechanical behavior, we exposed cells from a single donor to varying magnitudes of pressure gradient (10, 30, and 50 cmH2O, Fig. 3B) for 10 min, and also imaged LIS deformations after removal of sustained pressure (Fig. 3C). We found that the extent of LIS volume change was dependent on the magnitude of the pressure gradient applied (Fig. 3B). The relationship between applied pressure and resulting change in LIS volume at 600 s (about steady state) is shown in Fig. 3D; this nonlinear relationship is typical of biological tissues which show strain-dependent stiffening. On removal of sustained pressure at 600 s, the LIS volume increased, but the recovery process exhibited slower kinetics than the original collapse (Fig. 3C). The recovery of LIS volume appeared to be ongoing at the conclusion of the time course, but extending experiments beyond 1200 s led to increasing cellular uptake of dextran and loss of selective LIS staining (data not shown). Taken together, the imaging results demonstrate that LIS deformations in response to step increases in pressure are remarkably slow, largely reversible, and nonlinearly proportional to pressure magnitude.

Comparing predicted and measured EGFR activation kinetics

To measure the time course of EGFR activation under sustained compressive loading, we collected cell lysates at various intervals after initiation of continuous compressive stress. As described above, we employed an ELISA approach to detect the quantity of EGFR phosphorylated at tyrosine 1068 in each sample. We found that continuous compressive stress transiently increased phospho-EGFR levels with a peak 1.8 ± 0.3-fold increase at 180 s and a return to approximately baseline levels by 480 s (Fig. 4A).

We then employed a computational approach (24) to model the temporal changes in ligand concentration that would accompany the LIS volume changes observed in the preceding experiments. We used a finite element approach to solve the diffusion-convection equations governing ligand transport in a dynamically changing LIS geometry (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Fig. S2), assuming for simplicity one-dimensionality of fluid flow and ligand diffusion (24). We estimated the LIS width as a function of time w(t) from measured changes in LIS volume (average of the observations in Fig. 3A). We further assumed uniform ligand diffusivity within and outside the LIS (DLIS=Dout=120 μm2/s). The choice of ligand diffusivity, within the expected range for EGF-family ligands, had little effect on the overall kinetics of ligand accumulation (see Supplemental Fig. S3).

When plotted together on the same time scale, we observed a striking correlation between the onset kinetics and magnitude of ligand accumulation predicted from LIS volume changes and the measured change in EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). The tight correspondence between predicted and measured EGFR signaling, while correlative, strongly supports the hypothesis that mechanical stress is transduced into receptor activation through the gradual accumulation of autocrine ligands in the intercellular space. Beyond 180 s, the close correlation between predicted and observed EGFR activation diverged, likely reflecting tightly regulated EGFR down-regulation through mechanisms (e.g., phosphatase activity and receptor internalization; refs. 39,40,41,42)not incorporated in our ligand diffusion-convection model. The observation of a transient increase in EGFR activation in the presence of a sustained increase in ligand concentration is consistent with a vast body of prior experimental work (e.g., refs. 43,44,45,46,47).

To test whether the slow deformation of the LIS provides a mechanical filter that prevents cellular activation by transiently applied mechanical stresses, we exposed NHBE cells from a new donor to either 3, 10, or 180 s of transcellular pressure, then lysed cells and compared EGFR phohsphorylation at 180 s (Fig. 4D). The short durations were chosen for their physiological relevance to the approximate durations of normal and deep inspirations. The data derived from these experiments show that while sustained (3 min), mechanical stress evokes an increase in EGFR phosphorylation, and transiently applied (3 or 10 s) loads do not. These data support the concept that this mechanotransduction mechanism encodes a selective response to sustained loading.

Transcriptional analysis of EGFR-dependent mechanotransduction

The EGFR activation by compressive stress was both modest in degree and transient in duration, raising a question as to the importance of the signal in the overall cellular response to loading that emerges over the following minutes to hours (48). To gain perspective on the role EGFR activation plays in global, transcriptome-scale responses to sustained mechanical loading, we used a small-molecule EGFR inhibitor (AG1478; 1 μM) and compared transcriptional profiles from cells exposed to continuous compressive stress for 1, 3, and 8 h to time-matched controls in the presence and absence of AG1478. We focused our analysis on the set of mechanoresponsive genes differentially expressed in cells exposed to pressure, group P, relative to controls, C, and compared their differential expression in the presence of AG1478, groups P + A and A. At the most basic level, we expect EGFR-dependent mechanoresponsive genes to be differentially expressed in P/C, but not in P + A/A. On the other hand, EGFR-independent genes will remain differentially expressed in P + A/A. To each gene that was classified as mechanoresponsive, we thus applied a simple criterion (P+A/A<0.5∗P/C) to segregate genes into EGFR-dependent and -independent groups. In this way, we could evaluate the overall contribution of EGFR signaling to the totality of transcriptional responses evoked by sustained application of mechanical stress.

Focusing first on all mechanoresponsive genes, we identified 19 probes (representing 18 genes) increased after 1 h of continuous compressive stress, with 53 probes (representing 46 genes) and 49 probes (representing 34 genes) identified after 3 and 8 h of continuous compressive stress, respectively. For the complete list of mechanoresponsive genes at each time point, see Supplemental Data. To evaluate both the overall quality of the microarray analysis and our selection criteria for mechanoresponsive genes, we measured the expression levels of 20 genes (some at multiple timepoints) by qPCR, using RNA aliquots from the individual replicate experiments that had been pooled together for microarray analysis. The overall linear correlation between microarray and replicate PCR results for P/C was 0.81 (Fig. 5A), which was highly significant (P=2.1E-7; Supplemental Data). Similar results were obtained when the data were examined for rank correlation, which reduces the influence of extreme values (r=0.68, P=6.4E-5). Analysis of replicate experiments by qPCR identified eight gene and time point combinations that were statistically (P<0.05) increased in pressure samples relative to time-matched controls (Fig. 5A, open circles). The gene with the greatest mechanoresponsive signature by microarray that failed to confirm via qPCR was DUSP6 at 1 h. Its P/C value by microarray was 0.51 log fold, and its PCR log fold change was 0.48, with P = 0.08 (Fig. 5A). Our designated criteria for mechanoresponsive genes (0.52 log fold) excluded this gene, and also excluded several of the genes that reached statistical significance by qPCR (only 5 of the 8 genes that tested significant by PCR exceeded the 0.52 log fold threshold). These results highlight the relative stringency of the threshold we used in selecting mechanoresponsive genes, which minimizes the inclusion of false positives, but correspondingly, omits genes that might reach statistical significance when evaluated by qPCR.

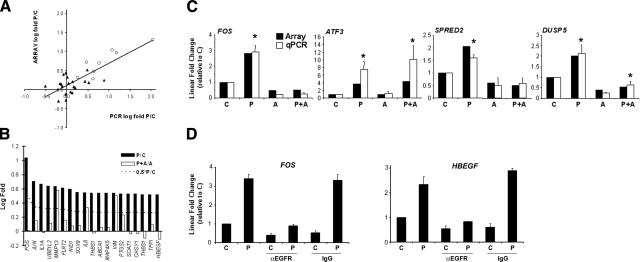

Figure 5.

EGFR-dependent transcriptomic response to compressive stress. A) Comparison of natural log fold changes in gene expression of pressure samples vs. time matched controls (P/C) measured by microarray anlaysis of pooled samples, and qPCR analysis of replicate samples (means of 3 independent experiments). Open circles indicate probes that reached statistical significance by qPCR. Cutoff for inclusion in mechanoresponsive gene list was 0.52 on the y axis. B) Rank-ordered mechanoresponsive probes (P/C) after 1 h continuous compressive stress, and their response to compressive stress in the presence of AG1478 (P+A/A). Criteria used to assess EGFR-independence are shown as a dashed line (P+A/A<0.5∗P/C). C) Comparison of qPCR results to microarray values that led to classification of 3 EGFR-dependent (FOS, SPRED2, and DUSP5) and 1 EGFR-independent mechanoresponsive genes (ATF3). *P < 0.05 for P vs. C or P+A vs. A. D) Changes in transcript levels for FOS and HBEGF, measured by qPCR, after exposure to compressive stress for 1 h in the presence of a neutralizing antibody against EGFR (20 μg/ml), or isotype control (IgG, 20 μg/ml). Cells from same donor as Fig. 4D were used. Data are means ± sd representative of 2 independent experiments; n = 2 wells/condition.

Segregating the mechanoresponsive probes into EGFR-independent and -dependent classifications, we found that 16 of 19 probes (84%) were EGFR dependent after 1 h of compressive stress (Fig. 5B), while 36 of 53 (68%) were EGFR dependent at 3 h, and only 17 of 49 (35%) at 8 h. To confirm the segregation of genes, we analyzed 4 mechanoresponsive genes in more detail, 3 classified as EGFR-dependent (FOS, DUSP5, and SPRED2), and 1 classified as EGFR-independent (ATF3). Three of 4 classifications were clearly confirmed by PCR (Fig. 5C). DUSP5 remained responsive to compressive stress in the presence of EGFR blockade, but from a 4-fold lower expression level. To test whether attenuation of transcriptional responses by AG1478 reflected bona fide EGFR-dependent genes, we performed additional qPCR analysis of FOS and HBEGF transcripts in the presence of a neutralizing antibody to EGFR, or an isotype control (Fig. 5D). These experiments confirmed the EGFR-dependent mechanoresponsiveness of these two genes. The overall picture that emerges from these analyses is of a dominant role for EGFR-dependent mechanotransduction in driving the early global transcriptional responses to sustained mechanical loading, with its influence waning as compressive stress continues for prolonged periods after the initial burst of EGFR activation. This conclusion holds even if more stringent thresholds for EGFR dependence are instituted. For instance, defining EGFR dependence by P + A/A < 0.33 ∗ P/C still results in 15/19 probes (79%) classified as EGFR-dependent at 1 h, and similarly defining EGFR dependence as P + A/A < 0.25 ∗ P/C leaves 14/19 probes (74%) classified as EGFR dependent.

Focusing our attention on individual mechanoresponsive genes and enriched ontological categories, we noted that several previously identified (26, 48, 49) mechanoresponsive genes (HBEGF, EREG, PLAUR, PLAT, EDN2) were identified in the current microarray analysis (see Supplemental Data). Strikingly, several other mechanoresponsive genes identified here have been previously identified as targets of EGFR signaling by others, including IL8 (50,51,52), VEGFA (50, 52), and THBS1 (53), supporting the primacy of EGFR in driving the early transcriptional response to mechanical stress. Among the most significant ontological categories at 1 h were several denoted “EGF” or “EGF-like,” containing the 4-gene set of NID1, PTGS2, HBEGF, and THBS1, further emphasizing the connection between mechanical stress, EGFR activation, and early transcriptional events. Full lists of significantly enriched ontological categories at each time point, including member mechanoresponsive genes, are provided in the Supplemental Data. Interestingly, at 3 h, gene ontology analysis identified MAP kinase phosphatase as a highly enriched category, with members DUSP5 and DUSP10. These genes, like DUSP6 mentioned above, encode dual-specificity phosphatases that contribute to feedback attenuation of MAP kinase activity (52, 54, 55). Similarly, we identified SPRED2, a negative regulator of ras-MAPK signaling (56, 57), as mechanoresponsive and EGFR-dependent in this system (Fig. 5C). Taken together, the microarray and qPCR results demonstrate a transcriptome-wide role for EGFR signaling in driving early (1–3 h) cellular responses to sustained compressive stress, and suggest that transcriptional events may mediate feedback attenuation to this mechanical stimulus.

DISCUSSION

Cells mount rapid responses to changes in their mechanical environment through a number of mechanisms that are typically localized intracellularly or at the cell surface (1, 3,4,5,6). Our results, in contrast, detail a mechanical signaling mechanism operating on a slower timescale through gradual accumulation of shed ligands in a slowly deforming extracellular space. The relatively slow nature of this process provides a unique means to tailor cellular responses to sustained loading while limiting responses to transient loads, thus providing one mechanistic explanation for cellular reactions that require persistent changes in the mechanical environment (26, 49). We established the presence of localized constitutive autocrine signaling activity, a necessary precondition for such a signaling mechanism, revealing cryptic ligand shedding normally masked by efficient receptor-mediated ligand capture. By directly comparing the kinetics of EGFR activation and LIS deformation through a computational model of ligand accumulation, we confirmed that ongoing constant-rate ligand shedding in a shrinking LIS is sufficient to account for both the magnitude and onset kinetics of receptor activation. Nobably, these results argue against any contribution from transactivation of EGFR (58, 59) by mechanical stress, which would necessarily evoke EGFR activation in excess of that predicted by geometric effects on the LIS. While the EGFR response to sustained loading was itself both modest and transient, its biological relevance was underscored by the widespread attenuation of early transcriptional responses in the presence of a small-molecule inhibitor of EGFR activity. Together, these results support a slow developing, dominant, receptor-specific response to compressive loading through autocrine signaling in a deforming LIS.

The LIS as an architectural feature of polarized epithelia was previously thought to serve two primary functions: to facilitate paracellular transport and to serve as a conduit for immune cell trafficking. Our results demonstrating ongoing autocrine signaling in a compliant LIS provide a third functional role for the LIS in mechanosensing. While autocrine loops were first identified as potential mediators of autonomous cancer cell growth (60), they are now widely recognized in a variety of cell types, tissues, and contexts (61), and our results suggest that their ongoing activity in the presence of interstitial deformations may constitute a distinct mode of mechanical signaling. The coupling of changes in intercellular spacing with autocrine signaling provides cells with a contact-independent readout of changes in cellular “crowding” applicable to both externally applied mechanical loads, as shown here, or rapid changes in cell number occurring during developmental processes or uncontrolled cellular proliferation. While the current investigation was focused on signaling in the LIS of a polarized epithelium, there is evidence that local interstitial autocrine signaling may also play a prominent role in cardiac mechanotransduction and remodeling (62, 63), suggesting the broader applicability and relevance of this mode of mechanical signaling.

The tight regulation and rapid reversal of EGFR phosphorylation we observed in response to sustained loading (Fig. 4A) is not surprising given the critical roles this receptor plays in development (64) and cancer (65). The phosphorylation status of the EGFR reflects a dynamic balance between cellular kinase and phosphatase activities (39, 41), with the balance tilted heavily in favor of phosphatases in normal high-density cultures (42). Despite the modest degree of EGFR phosphorylation induced under compressive loading, we observed a dominant transcriptome-wide role for EGFR-dependent mechanosignaling. These results emphasize the sensitivity of the EGFR network, and its broad-scale importance for epithelial gene expression (35). Moreover, our microarray results reveal EGFR-dependent expression of genes capable of feedback regulation (DUSP5,10 and SPRED2) of the EGFR signaling axis; these findings complement previously identified mechanosensitive-positive feedback mediators (26), and echo EGF-dependent networks identified in other epithelia (52).

While EGFR activation in sparse cell culture conditions is usually associated with proliferation and functions as such in undifferentiated airway epithelial cultures (66), responses to EGFR activation in highly confluent cells are biased toward modulation of differentiation. Indeed, in the intact airway and in confluent airway epithelial cultures, EGFR signaling is associated with promotion of a mucus secretory phenotype (67, 68). In agreement with this role, we have found that EGFR-dependent mechanosignaling contributes to mucus cell hyperplasia in response to chronic, intermittent compressive stress (69). Immunohistochemical evidence from human airways supports the notion that EGF receptors and ligands are basolaterally colocalized in airways (13,14,15,16, 70), though counterexamples of apical/basal segregation of EGF receptors and ligands emphasize the versatility of the EGFR system (17, 71). What functional roles might justify the energy expenditures necessary for constitutive EGF-family ligand shedding? In addition to a role in mechanosignaling, as demonstrated here, constitutive ligand shedding could provide ongoing signals to maintain or modulate epithelial differentiation states, or serve to tonically stimulate receptors at low levels, thus priming cellular machinery to respond to subtle changes in microenvironmental ligand availability.

An intriguing mystery that remains unresolved in our study is the physical origin of the slow interstitial deformations we observed in response to step increases in loading. Our experimental regimen is analogous to a standard creep-compliance mechanical test, where creep is the deformation ongoing after a step increase in load. Notably, creep and recovery in isolated cells are usually characterized by time constants much shorter than the ∼110 s observed here (72, 73), suggesting that the origin of the slow deformations might reside largely outside the cell. Strikingly, hydrogels and extracellular matrix-rich tissues such as the lung have been shown to exhibit creep characterized by long time constants similar to those we observed here (74, 75). The slow creep response in hydrated matrices can be attributed to the biphasic nature of these tissues, with a dense solid matrix contributing elastic properties and greatly retarding the flow of interstitial fluid (76, 77). The resulting mechanical properties of such a biphasic material can be further modified by electrostatic charge distributed throughout the solid matrix (78). In support of a biphasic characterization of the LIS, abundant evidence indicates that diffusion of small molecules within the LIS is significantly hindered in a size- and charge-dependent fashion (79,80,81), indicating that the LIS is not simply fluid-filled, but is rather a crowded molecular space. Together, these observations lead us to speculate that mechanical and electrostatic interactions between LIS fluid, basolateral cell surfaces and interstitial contents, such as the glycocalyx, play a prominent role in retarding the kinetics of LIS deformation under loading. This raises the possibility that variations in interstitial contents across tissues and disease conditions could modulate the kinetics of mechanical deformations, and tune cellular mechanical responses to varying timescales.

Taken together, our findings indicate for the first time that sustained mechanical loading leads to slow interstitial deformations coupled to gradual autocrine ligand accumulation and cognate receptor activation. The resulting mechanotransduction system provides a unique means to tailor cellular responses selectively to sustained mechanical loading. Such a mechanism could be particularly important in the lung and other mechanically dynamic tissues, where a variety of mechanisms are likely needed to specify appropriate responses to sustained vs. transient stresses (9, 82, 83). The slow, but robust, mechanical signaling response demonstrated here could thus provide an ideal means to ensure that energetically costly responses to mechanical stimuli are activated only when warranted by persistent changes in the mechanical environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Drazen, J. Fredberg, and D. Lauffenburger for helpful discussions. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL082856 and HL88028, and A.T.K. is funded by NIH NS040828.

References

- Chachisvilis M, Zhang Y L, Frangos J A. G protein-coupled receptors sense fluid shear stress in endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15463–15468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607224103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Tamada M, Dubin-Thaler B J, Cherniavskaya O, Sakai R, Tanaka S, Sheetz M P. Force sensing by mechanical extension of the Src family kinase substrate p130Cas. Cell. 2006;127:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses W B, Dejana E, Schultz D A, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz M A. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Botvinick E L, Zhao Y, Berns M W, Usami S, Tsien R Y, Chien S. Visualizing the mechanical activation of Src. Nature. 2005;434:1040–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature03469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B D, Overby D R, Mannix R, Ingber D E. Cellular adaptation to mechanical stress: role of integrins, Rho, cytoskeletal tension and mechanosensitive ion channels. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:508–518. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Izumo S. Mechanical stretch rapidly activates multiple signal transduction pathways in cardiac myocytes: potential involvement of an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. EMBO J. 1993;12:1681–1692. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyton S R, Kim P D, Ghajar C M, Seliktar D, Putnam A J. The effects of matrix stiffness and RhoA on the phenotypic plasticity of smooth muscle cells in a 3-D biosynthetic hydrogel system. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2597–2607. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarran R, Button B, Boucher R C. Regulation of normal and cystic fibrosis airway surface liquid volume by phasic shear stress. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:543–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.072304.112754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin D J, Drazen J M. Chronic effects of mechanical force on airways. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:563–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.072304.113102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux S, Esposito B, Merval R, Tedgui A. Differential regulation of vascular focal adhesion kinase by steady stretch and pulsatility. Circulation. 2005;111:643–649. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154548.16191.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux S, Tedgui A. Cellular mechanics and gene expression in blood vessels. J Biomech. 2003;36:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin D J, Dai G, Maly I V, Kikuchi T, Laiho L H, McVittie A K, Haley K J, Lilly C M, So P T, Lauffenburger D A, Kamm R D, Drazen J M. Mechanotransduction through growth-factor shedding into the extracellular space. Nature. 2004;429:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature02543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida S, Tamai S, Sekiguchi S, Shimizu N. Distribution of epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor in human lung: immunohistochemical and immunoelectron-microscopic studies. Respiration. 1994;61:161–166. doi: 10.1159/000196329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amishima M, Munakata M, Nasuhara Y, Sato A, Takahashi T, Homma Y, Kawakami Y. Expression of epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor immunoreactivity in the asthmatic human airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1907–1912. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9609040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polosa R, Puddicombe S M, Krishna M T, Tuck A B, Howarth P H, Holgate S T, Davies D E. Expression of c-erbB receptors and ligands in the bronchial epithelium of asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:75–81. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddicombe S M, Polosa R, Richter A, Krishna M T, Howarth P H, Holgate S T, Davies D E. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial repair in asthma. FASEB J. 2000;14:1362–1374. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.10.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer P D, Einwalter L A, Moninger T O, Rokhlina T, Kern J A, Zabner J, Welsh M J. Segregation of receptor and ligand regulates activation of epithelial growth factor receptor. Nature. 2003;422:322–326. doi: 10.1038/nature01440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Shively J D, Foley J S, Drazen J M, Tschumperlin D J. Differentiation-dependent responsiveness of bronchial epithelial cells to IL-4/13 stimulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L119–L126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00365.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinante F, Marchi M, Rigo A, Scapini P, Pizzolo G, Cassatella M A. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor/diphtheria toxin receptor and sensitivity to diphtheria toxin in human neutrophils. Blood. 1999;94:3169–3177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst S J, Stropp J Q. Pressure-volume and length-stress relationships in canine bronchi in vitro. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2522–2531. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler B, Lee R T, Randell S H, Drazen J M, Kamm R D. Molecular responses of rat tracheal epithelial cells to transmembrane pressure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L1264–L1272. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.6.L1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggs B R, Hrousis C A, Drazen J M, Kamm R D. On the mechanism of mucosal folding in normal and asthmatic airways. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1814–1821. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojic N, Huang A, Chung E, Tschumperlin D, So P T. Quantification of three-dimensional dynamics of intercellular geometry under mechanical loading using a weighted directional adaptive-threshold method. Opt Express. 2008;16:12403–12414. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.012403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojic N, Kojic M, Tschumperlin D J. Computational modeling of extracellular mechanotransduction. Biophys J. 2006;90:4261–4270. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K J, Schmittgen T D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu E K, Foley J S, Cheng J, Patel A S, Drazen J M, Tschumperlin D J. Bronchial epithelial compression regulates epidermal growth factor receptor family ligand expression in an autocrine manner. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:373–380. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0266OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R A, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay Y D, Antonellis K J, Scherf U, Speed T P. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett J N, Sanoudou D, Kho A T, Han M, Bennett R R, Kohane I S, Beggs A H, Kunkel L M. Gene expression profiling of Duchenne muscular dystrophy skeletal muscle. Neurogenetics. 2003;4:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s10048-003-0148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Kho A, Kenney A M, Yuk Di D I, Kohane I, Rowitch D H. Identification of genes expressed with temporal-spatial restriction to developing cerebellar neuron precursors by a functional genomic approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5704–5709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082092399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin D J, Shively J D, Swartz M A, Silverman E S, Haley K J, Raab G, Drazen J M. Bronchial epithelial compression regulates MAP kinase signaling and HB-EGF-like growth factor expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L904–L911. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00270.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr, Sherman B T, Hosack D A, Yang J, Gao W, Lane H C, Lempicki R A. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M, Wolfe D A. New York: Wiley; Nonparametric Statistical Methods. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Harris R C, Chung E, Coffey R J. EGF receptor ligands. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey P J, Coffey R J. Basolateral targeting and efficient consumption of transforming growth factor-alpha when expressed in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16878–16889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen G, Park S W, Nguyenvu L T, Rodriguez M W, Barbeau R, Paquet A C, Erle D J. IL-13 and epidermal growth factor receptor have critical but distinct roles in epithelial cell mucin production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:244–253. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger D A, Oehrtman G T, Walker L, Wiley H S. Real-time quantitative measurement of autocrine ligand binding indicates that autocrine loops are spatially localized. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15368–15373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab G, Klagsbrun M. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1333:F179–F199. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M, Yao S, Lin Y Z. Controlling epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated Ras activation in intact cells by a cell-permeable peptide mimicking phosphorylated EGF receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27456–27461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostman A, Bohmer F D. Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatases. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resat H, Ewald J A, Dixon D A, Wiley H S. An integrated model of epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Biophys J. 2003;85:730–743. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74516-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A R, Tischer C, Verveer P J, Rocks O, Bastiaens P I. EGFR activation coupled to inhibition of tyrosine phosphatases causes lateral signal propagation. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:447–453. doi: 10.1038/ncb981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorby M, Ostman A. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase-mediated decrease of epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in high cell density cultures. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10963–10966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoev B, Ong S E, Kratchmarova I, Mann M. Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen U B, Cardone M H, Sinskey A J, MacBeath G, Sorger P K. Profiling receptor tyrosine kinase activation by using Ab microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9330–9335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633513100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J V, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa S, Ozaki Y, Fujita K, Kuroda S. Prediction and validation of the distinct dynamics of transient and sustained ERK activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:365–373. doi: 10.1038/ncb1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeberl B, Eichler-Jonsson C, Gilles E D, Muller G. Computational modeling of the dynamics of the MAP kinase cascade activated by surface and internalized EGF receptors. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nbt0402-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu E K, Cheng J, Foley J S, Mecham B H, Owen C A, Haley K J, Mariani T J, Kohane I S, Tschumperlin D J, Drazen J M. Induction of the plasminogen activator system by mechanical stimulation of human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:628–638. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0040OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin D J, Shively J D, Kikuchi T, Drazen J M. Mechanical stress triggers selective release of fibrotic mediators from bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:142–149. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0121OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J G, Vincent P W, Klohs W D, Fry D W, Leopold W R, Elliott W L. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8 as biomarkers of antitumor efficacy of a prototypical erbB family tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:938–947. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L M, Torres-Lozano C, Puddicombe S M, Richter A, Kimber I, Dearman R J, Vrugt B, Aalbers R, Holgate S T, Djukanovic R, Wilson S J, Davies D E. The role of the epidermal growth factor receptor in sustaining neutrophil inflammation in severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:233–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Citri A, Shay T, Lu Y, Katz M, Zhang F, Tarcic G, Siwak D, Lahad J, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Vaisman N, Segal E, Rechavi G, Alon U, Mills G B, Domany E, Yarden Y. A module of negative feedback regulators defines growth factor signaling. Nat Genet. 2007;39:503–512. doi: 10.1038/ng1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Ono M, Uchiumi T, Ueno H, Kohno K, Sugimachi K, Kuwano M. Up-regulation of thrombospondin-1 gene by epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor beta in human cancer cells–transcriptional activation and messenger RNA stabilization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1574:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyse S M. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D M, Keyse S M. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signalling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene. 2007;26:3203–3213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakioka T, Sasaki A, Kato R, Shouda T, Matsumoto A, Miyoshi K, Tsuneoka M, Komiya S, Baron R, Yoshimura A. Spred is a Sprouty-related suppressor of Ras signalling. Nature. 2001;412:647–651. doi: 10.1038/35088082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Hisamoto T, Akiba J, Koga H, Nakamura K, Tokunaga Y, Hanada S, Kumemura H, Maeyama M, Harada M, Ogata H, Yano H, Kojiro M, Ueno T, Yoshimura A, Sata M. Spreds, inhibitors of the Ras/ERK signal transduction, are dysregulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma and linked to the malignant phenotype of tumors. Oncogene. 2006;25:6056–6066. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel N, Zwick E, Daub H, Leserer M, Abraham R, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer O M, Hart S, Gschwind A, Ullrich A. EGFR signal transactivation in cancer cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1203–1208. doi: 10.1042/bst0311203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M B, Roberts A B. Autocrine growth factors and cancer. Nature. 1985;313:745–747. doi: 10.1038/313745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley H S, Shvartsman S Y, Lauffenburger D A. Computational modeling of the EGF-receptor system: a paradigm for systems biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly I V, Lee R T, Lauffenburger D A. A model for mechanotransduction in cardiac muscle: effects of extracellular matrix deformation on autocrine signaling. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:1319–1335. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000042221.61633.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka J, Prince R N, Huang H, Perkins S B, Cruz F U, MacGillivray C, Lauffenburger D A, Lee R T. Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and degradation of connexin43 through spatially restricted autocrine/paracrine heparin-binding EGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10622–10627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501198102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen P J, Warburton D, Bu D, Zhao J S, Berger J E, Minoo P, Koivisto T, Allen L, Dobbs L, Werb Z, Derynck R. Impaired lung branching morphogenesis in the absence of functional EGF receptor. Dev Biol. 1997;186:224–236. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T J, Bell D W, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto R A, Brannigan B W, Harris P L, Haserlat S M, Supko J G, Haluska F G, Louis D N, Christiani D C, Settleman J, Haber D A. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriola P C, Robertson A T, Rusnak D W, Diaugustine R, Nettesheim P. Epidermal growth factor dependence and TGF-α autocrine growth regulation in primary rat tracheal epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1992;152:302–309. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041520211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama K, Fahy J V, Nadel J A. Relationship of epidermal growth factor receptors to goblet cell production in human bronchi. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:511–516. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama K, Dabbagh K, Lee H M, Agusti C, Lausier J A, Ueki I F, Grattan K M, Nadel J A. Epidermal growth factor system regulates mucin production in airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3081–3086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J A, Tschumperlin D J. Chronic intermittent mechanical stress increases MUC5AC protein expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:459–466. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0195OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polosa R, Prosperini G, Leir S H, Holgate S T, Lackie P M, Davies D E. Expression of c-erbB receptors and ligands in human bronchial mucosa. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:914–923. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner J W, Kim E Y, Ide K, Pelletier M R, Roswit W T, Morton J D, Battaile J T, Patel A C, Patterson G A, Castro M, Spoor M S, You Y, Brody S L, Holtzman M J. Blocking airway mucous cell metaplasia by inhibiting EGFR antiapoptosis and IL-13 transdifferentiation signals. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:309–321. doi: 10.1172/JCI25167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand G, Millet E, Fabry B, Butler J P, Fredberg J J. Linearity and time-scale invariance of the creep function in living cells. J R Soc Interface. 2004;1:91–97. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2004.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek G, Wiltz D C, Athanasiou K A. Contribution of the cytoskeleton to the compressive properties and recovery behavior of single cells. Biophys J. 2009;97:1873–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin M F, Suki B, Stamenovic D. Dynamic behavior of lung parenchyma in shear. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:1880–1890. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.6.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu M T, Huang J C, Yeh G C, Ho H O. Characterization of collagen gel solutions and collagen matrices for cell culture. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian G A, Chahine N O, Basalo I M, Hung C T. The correspondence between equilibrium biphasic and triphasic material properties in mixture models of articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2004;37:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00252-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mow V C, Kuei S C, Lai W M, Armstrong C G. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W M, Hou J S, Mow V C. A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:245–258. doi: 10.1115/1.2894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovbasnjuk O N, Bungay P M, Spring K R. Diffusion of small solutes in the lateral intercellular spaces of MDCK cell epithelium grown on permeable supports. J Membr Biol. 2000;175:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s002320001050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P, Bungay P M, Gibson C C, Kovbasnjuk O N, Spring K R. Diffusion coefficients in the lateral intercellular spaces of Madin-Darby canine kidney cell epithelium determined with caged compounds. Biophys J. 1998;74:3302–3312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78037-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring K R, Hope A. Size and shape of the lateral intercellular spaces in a living epithelium. Science. 1978;200:54–58. doi: 10.1126/science.635571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button B, Picher M, Boucher R C. Differential effects of cyclic and constant stress on ATP release and mucociliary transport by human airway epithelia. J Physiol. 2007;580:577–592. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarran R, Button B, Picher M, Paradiso A M, Ribeiro C M, Lazarowski E R, Zhang L, Collins P L, Pickles R J, Fredberg J J, Boucher R C. Normal and cystic fibrosis airway surface liquid homeostasis. The effects of phasic shear stress and viral infections. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35751–35759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505832200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.