Abstract

Nursing critically ill patients includes planning and performing safe discharges from Intensive Care Units (ICU) to the general wards. The aim of this study was to obtain a deeper understanding of the main concern in the ICU transitional process—the care before, during, and after the transfer of ICU patients. Interviews were conducted with 35 Swedish nurses and analysed according to grounded theory. The main concern was the nurses' “struggling with a gap.” The “gap” was caused by differences in the altered level of care and contributed to difficulties for nurses encountering an overlap during the transitional care. The categories: sheltering, seeking organizational intertwining and striving for control are related to the core category and were used to generate a theory. The nurses sought improved collaboration, and employed patient-centred routines. They wanted access to necessary tools; they relayed or questioned their own competence and sought assurance of the patients' ability to be transferred. If the nurses felt a loss of control, lack of intertwining and lack of collaboration, they sheltered their patients and themselves. Intertwining was more difficult to perform, but actually even more important to do. With knowledge about ICU transitional care, collaboration, routines, and with an organization that provides an educational environment, the process could be improved.

Keywords: Collaborating, discharge process, ICU discharge, grounded theory, nursing, transitional care

Introduction

Transition is a well-known term and means a process or period's characteristics of change, passing from one state, stage, form, or activity to another. The transition process from Intensive Care Units, ICU, to the general ward involves the patient, their relatives, and the staff. Critically ill patients in the ICU often experience many transitions, from the time they are acutely sick until they recover and return to their homes (Chaboyer, James & Kendall, 2005). The transfer of patients from the ICU is an everyday procedure. It is an accepted part of the ICU nurse's routine work, but also an important element of providing quality care (Odell, 2000). There are approximately 40,000 patients a year admitted to Swedish Intensive Care, and it is expensive care (URL 1). Critical care beds are a finite resource, and the decision to transfer depends both on the individual's physical condition and on the demand for beds (Gibson, 1997). In this study, ICU transitional care is used and defined as “care provided before, during and after the transfer of an ICU patient to another care unit that aims to ensure minimal disruption and optimal care for the patient. This care may be provided by ICU nurses, acute care nurses, physicians and other healthcare professionals” (Chaboyer et al., 2005). Discharge planning is a part of ICU transitional care. It is a part of the process that aims to provide continuity of care for the patients. The effects of a poorly coordinated discharge can lead to readmission to the ICU and also avoidable deaths. If the transfer for the individual patient is accompanied by scarce, inadequate or untimely knowledge or preparation, it may be perceived as a threat to security (Whittaker & Ball, 2000).

It is well known that patients in a critical care environment may suffer both psychological and physical problems caused by the stress of being in the ICU (Coyle, 2001; Cutler & Garner, 1995; Gustad, Chaboyer & Wallis, 2008). The terms transfer anxiety or relocation stress are used for the psychological and physical problems that transferring causes for the patient (McKinney & Deeny, 2002). This stress may be exacerbated following transfer to a general ward. The anxiety is a common problem for patients and relatives, and both pre- and post-discharge are critical areas (Coyle, 2001). In the critical care environment, patients are often not able to express and communicate their own will either because of their present sedation or altered mental status. Hence, their relatives often find themselves in a stressful situation in an unfamiliar environment. The length of a patient's stay in the ICU varies and can be from less than 24 h to a stay as long as several months (Watts, Gardner, & Pierson, 2005). Earlier research indicated that ward nurses feel that caring for recently discharged patients from the ICU is stressful (Hall-Smith, Ball & Coakley, 1997). It is important that all healthcare professionals involved in the care of critically ill patients recognize the benefits of discharge planning for patients and their families (Coyle, 2001). The topic is an issue for medical research as well as for nursing research (Ball, 2005). Earlier studies often aim to study the relocation stress in the transfer, and therefore, this study aims to obtain a deeper understanding of the main concerns in the ICU transitional process as experienced by nurses in intensive care units and general wards in Sweden. We strive to illuminate how nurses handle the process and to identify problems during the process. This study is a part of a larger project that endeavours to illuminate the process called ICU transitional care with a grounded-theory approach.

Aim

The aim of this study was to obtain a deeper understanding of the main concerns in the ICU transitional process as experienced by nurses in intensive care units and general wards in Sweden.

Method

Grounded theory (GT), specifically the Glaserian version of GT, was selected as suitable in this qualitative study of the main concerns in the ICU transitional process as experienced by nurses in intensive care units and general wards in Sweden (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This version of GT, the classical version, seems to be ontologically closely positioned to positivism, which claims that only one real reality exists. According to Hallberg (2006), although Glaser never explicitly expresses this thought, he seems to assume an objective reality and a neutral researcher who discovers data in an objective way.

Participants and procedure

The participants have been open sampled, meaning that we sought a maximum variation of experiences in the group in order to obtain descriptions from contrasting milieus and backgrounds (Hallberg, 2006). To acquire this sort of heterogeneity in the group, different groups of nurses involved in ICU transitional care have been recruited. The nurses were recruited in three ICUs and five general wards in two different hospitals in Sweden. One hospital was located in the middle of Sweden, with around 3000 employees. The other hospital was located in the capital of Sweden, with around 4000 employees. The ICUs and wards specialized in surgical, medical, or general fields. Data was collected between February 2008 and October 2008. The total numbers of informants were 35 Swedish nurses, of which five were male and 30 female. The data was collected from focus groups and individual interviews for variation and heterogeneity in the data (see Table I).

Table I.

Overview of informants and interviews in chronological order.

| Interview | Informants recruited from | Years of experience as RN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Focus group | Intensive care unit | 10–25 |

| 2 | Focus group | Intensive care unit | 10–20 |

| 3 | Focus group | Intensive care unit | 11–24 |

| 4 | Focus group | A medical ward | 0.5–25 |

| 5 | Focus group | A surgical ward | 3–15 |

| 6 | Focus group | A medical ward | 3.5–33 |

| 7 | Individual | Intensive care/surgical ward | 20 |

| 8 | Individual | A surgical ward | 25 |

| 9 | Individual | A surgical ward | 17 |

| 10 | Individual | A surgical ward | 16 |

| 11 | Individual | Intensive care unit | 7 |

| 12a | Individual | Intensive care unit | 10 (as ICU nurse) |

| 13a | Individual | Intensive care unit | 14 |

aTheoretical saturation fulfilled.

In a focus group interview, every group should have a purpose, its specific focus. Focus groups can be a useful methodology when investigating people's attitudes and motives (Wibeck, 2000). In order to include the individual nurse's experience of ICU transitional care, seven individual interviews were added to the study. The interviews were conducted at the respondents' workplaces. The nurse in charge selected the respondents by asking nurses if they had interest in the study and following up with those who answered affirmatively. Written information about the aim of the study was sent to all the nurses. Each interview lasted 0.45–1.5 h.

The initial question was the same in all interviews and was as follows: “Can you describe how the ICU transitional care process is conducted and your feelings regarding it?” Follow-up questions were asked during the interview concerning the care before, during, and after the transfer of a patient from ICU to the general ward.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed into written text. Analysis was started immediately after the first interview and continued simultaneously. The overall coding process was made by open coding, line by line, and incident by incident followed by selective coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding.

Open coding

Open coding is the initial step of theoretical analysis that pertains to the discovery of categories and their properties. During the open coding, data was broken down into incidents and closely examined for similarity and differences (Glaser, 1992). The first author performed the coding process; the author made handwritten codes in the margin that sought activity in the data, trying to “run the data open,” and questioning “What is this data a study of?” The initial codes were sharpened to obtain the best fit, and when the categories emerged, they were named depending on their meaning and also renamed to obtain the best fit. The categories emerged from the following question: “What category or property of category does this incident indicate?” The number of categories was also reduced as they were renamed.

The emerging codes, categories, and properties were all compared with other data to explore variations, similarities, and differences in data. Finally, we asked the following question: “What is really going on in the data?” We tried to raise the analysis to an abstract level. The questions used for the constant analysis originated from Glaser's description of data analysis (Glaser, 1978). The authors wrote and compared memos comprising their associations, reflections, and ideas after each interview. Theoretical saturation was fulfilled when new data did not add new information to the theory (Hallberg, 2006).

Focused selective coding

The open coding ended when the core category appeared (Glaser, 1992). The core category answered the following question: “What was the main problem for the ICU nurses and the ward nurses?” Finally, the data analysis resulted in one core category; the main concern for the nurses was “struggling with a gap.” The theory was delimited to the core category. Three categories emerged which were related to the core category. The core category became a guide for further questioning (Glaser, 1978). In our study, the follow-up questions in the last five interviews had been theoretically sampled after the core category emerged.

Theoretical coding

The third step of the analysis, theoretical coding, has been a way to conceptualise how categories and substantive codes may relate to each other as a hypotheses to be transformed into a theory (Glaser, 1978). We examined the categories thoroughly and found relationships between the categories, and connections between the core category and the other categories. Table II shows the categories and how they are grounded in the data.

Table II.

Illustration of steps in coding process: core category, categories, subcategories, and how they are grounded in data.

| Interview text | Subcategory | Category | Core |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning is the most important! Nowadays, long-term planning hardly exists. | Wishing for routines that facilitate patient centeredness | Seeking organizational intertwining | |

| … For example, if we had planning in time, the physician in charge for the ICU that week could start planning the first day of the week, and then, we could prepare for the actual patient to move later that week. Then, you could write your epikris and prepare the ward for things that they may have to get …. | Wanting access to the necessary tools | Striving for control | |

| I would say that it is absolutely the most important that I, as a nurse, am totally convinced that the patient is well-prepared physically, so that their medical status is in the condition needed for an altered level of care …. So, there is no serious setback for the patient at the ward. … | Defending the patients Seeking assurance of the patients' ability | Sheltering Striving for control | Struggling with a gap |

| Sometimes, the patients have supplements that we never have seen before …. We do not have the competence and knowledge for that! …. | Relying on or questioning one's own ability | Striving for control | |

| … Often, nobody sees you and notices that you are there…. You do not want to feel like a bit of the wallpaper when you are waiting for the patient at the | Looking for affinity | Sheltering | |

| ICU …. One almost apologizes for being there …. | Seeking improved collaboration | Seeking organizational intertwining |

Ethical considerations

Ethical permission from the northern ethical board was obtained for the study (D- number 07–159). However, in this study, no medical records were used, and no patients participated. Before every interview, the participants were verbally informed and given written material stating the purpose of the study, that the data would be handled confidently, and that they had the right to withdraw at any time. Written consent was obtained from the head of the clinic. The nurses expressed their feelings that the topic was important for their professional work, and, therefore, they felt free and willing to be part of the study.

Findings

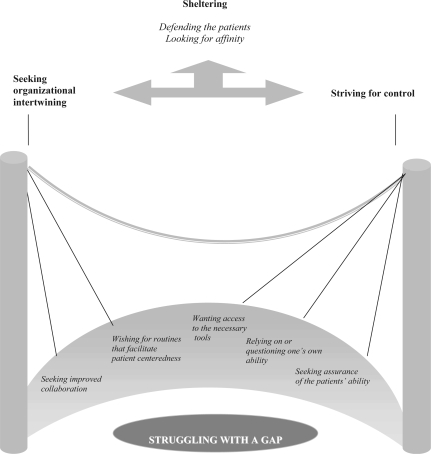

The core category and the main concern for nurses in the ICU transitional were their struggling with a gap in care between the ICU and the ward. The gap was caused by differences in the altered level of care and contributed to difficulties for the nurses in the overlap in the ICU transitional care process. These differences were seen in the nurses' competence, focus, and environment. The three other categories were related to the core category, and generated a theory describing the main concern for nurses involved in ICU transitional care and how the nurses handle the problem (see Figure 1). According to the nurses they were sheltering and seeking organizational intertwining and were also striving for control over the situations caused by the gap. The strategy sheltering described how the nurses were defending the patients and looking for affinity. The category, seeking organizational intertwining described the seeking for an improved collaboration between the ICU and the general ward and a wish for routines that facilitated patient centeredness, so the gap would be easier to handle. The third strategy described how the nurses were striving for control, which meant that they wanted access to the necessary tools for their nursing care and were relying on—or questioning their own competence, so that they were confident that they were competent and able to care for the patients for which they were responsible. They also wanted to be certain that the patients' recovery were sufficient for the ward staffs' competence, and were seeking assurance of the patient's ability. The theory showed that if the nurses felt a loss of control and lack of intertwining and collaboration, they sheltered their patients. The ability to perform the intertwining was negatively affected, and instead they sheltered, even though the need for collaboration and intertwining was even more salient. The categories and their subcategories were linked together as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustrating the main concern for the nurses: struggling with a gap. The three categories—sheltering, seeking organizational intertwining, and striving for control—are related to the core category. The bridge over the gap is built by the properties of two categories. All categories are connected with each other.

Struggling with a gap

The main concern, struggling with a gap, was a problem for the ICU nurses and the ward nurses. The gap consisted of cultural differences in the environment, differences in the nurses' competence, and uncertainty about how to communicate. The gap influenced the nurses' work between the departments and their own unit. The ICU nurses were, to a great extent, medically focused; they talked about saving the patients' lives, and how their actions were immediate and extremely controlled, always managing and monitoring. The ward nurses' care focused more on supporting the patients' strengths, and monitoring was a minor part of their care.

The dynamic between the ICU nurses and the ward nurses also influenced the nurses' struggles with a care gap, frequently in a negative manner. The differences in the care culture made the nurses feel safe in their own environment and also feel a shelter within the own group. The gap was maintained by lack of collaboration and lack of liaison between the wards and the ICUs. The ICU nurses expressed that they were well aware of the differences connected to an altered level of care and thought that it should be considered in the planning. The ward nurses indicated that this gap also was obvious for the patients and relatives and that they had to support the patients and their relatives through the gap caused by an altered care culture. According to the ICU nurses it was important that they did not confirm the patients' or relatives' mistrust and anxiety before and during the transfer.

It is important that we give the patient courage and trust before the actual discharge, one has to inform and support the patients and tell them that they actually are getting better and that they will manage the new level of care. (ICU nurse)

The nurses expressed the sense that because of the differences between the ICU and the general wards, it was important that their level of care was adjusted to patients' medical statuses. The altered staff ratio between the ICU and the general ward was visible also in the fact that ICU nurses often had a physician in charge near the patient, while the ward nurses more seldom had a physician at the ward. At the ICU, there were fewer—but often sicker—patients being cared for, compared to the general ward where nurses were responsible for many more. The ward nurses expressed that they sometimes felt overwhelmed, stressed, and tired when they knew that they would receive a patient from ICU, because of the extra workload involved. During the patients' first days at the ward—after the patient was transferred from ICU—the ward nurses sometimes had difficulties handling patients or relatives who expressed that they were used to obtaining help more immediately in the ICU.

I think that the staff ratio mirrors in the relation … I mean if they are calling for you at six pm and want help, and you don't have the time then, they are very disappointed. And, it's difficult, difficult to make them understand … (Ward nurse)

According to the nurses, the differences in the environment greatly contributed to the cultural gap. The environmental differences affected the nurses, especially since the patients and relatives reacted to the sudden environmental change in their care. The technological environments in the ICUs were described as noisy and disturbing, and ICU nurses or other staffs were always close. The patients were continually monitored and attached to machines. The general ward's environment was described as calmer and with more possibilities to take action personally. According to ward and ICU nurses, the patient and/or relatives sometimes felt a sense of relief when leaving the noisy ICU and moving to a calmer ward. Alternatively, the differences also often contributed to anxiety. The gap influenced the nurses' work situation, and it simplified matters if the gap was reduced.

Sheltering

The cultural differences made the nurses seek shelter in their own and well-known area, where they sought affinity with their own group and defended the patients and their relatives.

Looking for affinity

There existed visible dynamics between the nurses in the different departments; the nurses felt safe with their own group and often questioned the others, looking for affinity within their own group. They often talked in “us and them” terms, and according to many ward nurses, they sometimes felt insecure, frustrated, and of less worth when they met ICU nurses, especially in the ICU ward. In addition, the actual technological environment was unknown and made the ward nurses feel insecure.

You can feel unbelievably “small” when you are getting a patient from ICU … Their language is totally different and if you ask what it means, you can really be questioned. I sometimes feel like a fly on the wall … (Ward nurse 1)

Yes, you want to be noticed and to be seen when you are going in the ICU … (Ward nurse 2)

Good encounters and confirmation were important factors; the ward nurses wanted to be seen and met respectfully and equally when they came to the ICU ward. In addition to the importance of good encounters between the two wards, it was also significant to understand instead of questioning each other. The ward nurses expressed that one of the important bricks in their workplace was a visible, mutual understanding of both workplaces' situations and competences. The ICU nurses also expressed that the relationship with the ward nurses sometimes needed improvement. Mostly, their wishes concerned proper communication, and they wanted to erase the feelings of counteraction from the ward nurses concerning when to come and actually move the patient from the ICU.

Defending the patients

The nurses were often worried about the patients' well-being during the process. The ward nurses often took action to defend “their own patients,” especially if the patients were well known to the staff at the ward. They sometimes visited or called ICU to get information concerning the patient's status. For the ICU nurses, a great deal of their work concerned negotiations with the physicians, defending their patients regarding when and if the patients were ready to be discharged.

I think that I always need to slow the discharge … Yes! I think that they are transferred way too soon nowadays … Yes, I may have seen the patient many more days than the physician and know how fragile he really is, and then the physician comes and takes a look and says—ready for the ward … You need to know that the patient is medically able to move to the ward. (ICU nurse)

Because of downsized numbers of hospital beds, the nurses often needed to compromise their own ideals regarding how transitional care should be handled. The nurses felt that the focus in ICU transitional care was seldom on the patients, although they often tried to be their advocate and counsellor. More often, the participants expressed that the focus was all on moving the patient to another clinic and making a new bed for another patient in need; patient-centeredness was forgotten. This way of thinking concerned the nurses.

I think it is because everyone is thinking of their own needs and forgets the patient's experience of their journey. I think-that many think that I will do my job, and then others can take over … (ICU nurse)

Seeking organizational intertwining

Strategies of how to intertwine and overlap ICU transitional care were important for handling the gap, and an ICU nurse said: “The process should be like a net, where no mesh is broken and it is just continuing.” The process was described as unclear by the ICU nurses and often determined by whatever the physician for the day wanted to do. When nurses and doctors could create collaboration between departments, and use similar routines that facilitated patient centeredness, ICU transitional care was carried out more successfully.

Seeking improved collaboration

Collaboration between the ICU and general ward was of great importance for creating organizational intertwining and was sometimes used (and sometimes not). When the icu staff and the ward staff collaborated, it was often to secure the transfer of a patient with obvious special needs, so that no readmission to the ICU would occur.

This one time, they cooperated between our clinics among the discharge, but you got the feeling that it was only because that they didn't want to have the patient return again … (ICU nurse)

If the patient and the relatives met with the ward nurses before the discharge, and with the ICU nurses after the discharge, for a follow up, this created an intertwining. However, this sort of collaborating was more often expressed as a wish from the nurses than was actually performed. Both ICU and ward nurses said that providing information about the ward was important for a successful transition. This information varied greatly depending on which nurse was in charge of the actual patient because of the lack of intertwining and missing routines in ICU transitional care. However, the ICU nurses sometimes felt it difficult to provide the ward's information to the patients and the relatives. They did not always have actual information concerning the routines, etc. to give to the patient.

Intertwining with a liaison nurse was also described as a successful way of handling transitional care. The liaison nurse was someone in charge of and responsible for organizing transitional care, creating meetings with different team members and planning for the follow-up of possible future needs for the patients. This meeting provides the liaison nurse the opportunity to inform the ward nurses of the transfer, giving them time to prepare for the needs of taking over the patient.

Collaboration with the departments was also performed when the ward nurses consulted the ICU nurses to learn new supplements/procedures.

…We had this patient with a unfamiliar tracheotomy that made many nurses anxious… The ICU nurses were here a lot before the discharge and demonstrated how to proceed the suction… We also knew that the ICU nurses always were available for support. (Ward nurse)

Wishing for routines that facilitate patient centeredness

The nurses expressed a desire for routines that facilitated patient-centeredness and wanted strategies to use with the team members and the clinics involved. They wanted routines that facilitated patient-centeredness and wished that the caregivers would take responsibility for the individual, instead of only considering the advantages for their own unit. The nurses were aware that the planning had to consider the individual patient's needs, as well as general routines in transitional care, so intertwining could be accomplished. If there were strategies that described how to handle the whole ICU transitional care process, the planning would be simplified. If the nurses had routines to rely on, they could provide safer and better transitions for patients and their relatives. Set strategies would also simplify matters for the staff involved in care when another physician was put in charge.

You have to have a strategy, that's what it is all about. Every ICU should have clarity in what routines to use when moving an intensive care patient to the ward. That is where to start! (ICU nurse)

The ICU nurses expressed ambiguity concerning what authority and responsibility they had in planning the process; they relied heavily on the physicians' decisions. However, they felt that they often possessed a great deal of influence in the process. The ward nurses felt absolutely no influence in the ICU transitional care process, and their own role in it was undefined. They expressed a wish not only to see to their patients' care but see the whole chain in the journey of the patients' transitional care and to take responsibility for the care after or before their own department.

Striving for control

When the patient was about to be transferred, the control of the patient was transferred from the ICU nurses to the ward nurses. The ICU nurses and the ward nurses strove for control, wanted access to necessary tools, relied on questioning their competence, and sought assurance of the patients' ability to accept the altered level of care.

Wanting access to the necessary tools

The ICU nurses felt that one of their tools for providing good care was connected to the opportunity to plan the transfer properly. They wanted to prepare both the ward and the patient very well for the transition so that care could be continued properly. If the patient needed some unusual supplement at the ward, early planning was important so that the ward nurses did not miss things when the patient arrived.

The relay-race baton has to be given away in a proper way, so that the ward nurse gets the opportunity to continue the care for the patient. (ICU nurse)

Both the ICU nurses and the ward nurses felt that the decisions for the patient needed to be well documented, and that the physician had to write the prescriptions so that the ward nurses could more easily take control. Written nursing documentation was an important tool in this situation. There were differences in the hospitals' documentation systems. One of the hospitals had a single overall system for the hospital, which enabled the ward nurses to be able to read about their patients in ICU. Ward nurses prepared by reading the patients' medical story before receiving a new patient in the ICU. By doing this, the nurses could more easily achieve control. This preparation was not performed at the other hospital; the ward nurses were not given the opportunity to read the ICU journals and, therefore, knew little about the patients. If they were receiving an ICU patient with extended care needs, the ward nurses expressed that one important tool for them was an adequate number of staff. This was vital for the both patients' security as well as for nurses' safety.

The informational tools were also communicated in a verbal report between the ICU nurse and the ward nurse. The ward nurses often thought that the verbal reports were too long and extensive and often possessed a medical focus that did not always seem needed. The ICU nurses were driven by a need to hand over all the information. They felt that the ward nurses needed to know the many things that occurred during the patients' ICU care. The ICU nurses partly used the same language when reporting to other ICU nurses; sometimes, it was difficult for them to change their way of communication.

I think that we much too often speak our medical language when reporting to the ward nurses. (ICU nurse)

Relying on or questioning ones own ability

It was important that the ICU and ward nurses felt confident in their abilities to care for the patients. Most participants in the study expressed a wish to gain control, which was often connected to their feelings of their competence in caring for the patients. In the hospitals, there were differences in how ward nurses experienced unfamiliar things in the care of their patients. If educational support was provided for the ward nurses, feelings of trust were visible, and they relied on their competence more easily. With support and education, the ward nurses felt curious about developed care and were also proud of their competence.

I think that our ward has quite an intense educational approach! … Our chief is providing time for education, and you can really feel that …. We think that new things are nice to see, and our attitude is that developing is good! This is an environment that encourages knowledge. (Ward nurse)

If the ward nurses sensed a lack of control, their feelings of unsafeness and insecurity could aggravate the collaboration between the departments, and if so, the gap remained. Hence, if this support and an educational environment were absent, feelings of insecurity emerged if a patient from ICU needed new and unusual care. This insecurity and frustration made the collaboration with the ICU nurses more difficult, since the ward nurses were less willing to receive such a patient from the ICU.

The ward nurses sometimes felt frustration about differences in their authority compared with the ICU nurses, and felt insecurity when they were told to do things that they did not usually do. These things could, for example, be that they were told to take away supplements from the patient, or perform controls that they did not usually do.

I can be confused when I am getting a patient from the ICU, there is a nurse just like me that is reporting, but we can do different kinds of things, they are doing things that for us must be prescribed by an physician …they are working so much more independently … I mean, what if we are doing something wrong! (Ward nurse)

Nurses often leaned on collegial support when they were confronted with new situations. If their colleagues' competence was not enough support, they questioned their own competency in the ward and feelings of insecurity emerged. Occasionally, the ward nurses went to visit the nurses at the ICU and learn in advance if there were unusual elements of care that would need to be handled. One of the nurses' suggestions for handling the negative differences concerned the nurses' competence, was that the ward nurses should be given opportunities to visit the ICU and work with an ICU nurse for a few days. This experience could improve their understanding of each other and, above all, the patients' experience in the ICU transitional journey.

Seeking assurance of the patients' ability

Both the ICU nurses and the ward nurses sought assurance that the patients were able to handle the altered level of care, as this was of great importance for the nurses' feelings of control and competence. The nurses wished that the level of care should be adjusted to the patients needs. They wanted to be certain that the patients' recoveries were sufficient for the resources that were available at the ward. Sometimes, however, a patient was moved to the general ward when it was known that he or she was soon going to die. These patients were moved to obtain a calmer environment for the patient and, above all, his or her relatives. Prior to the transfer, the ICU nurses sought signs confirming the patients' ability to transition to an altered level of care. The timing of discharge was crucial, and the inclusion criteria for moving from the ICU could vary. Sometimes, the nurses stopped a discharge when it was occurring too fast, and sometimes, they pushed it through and made it go faster. The time of preparation for the transfer and the discharge was sometimes minimal, and the decisions for the discharge were made “over a day.” The nurses could not always offer an explanation for the length of times they spent deciding to transfer a patient. Sometimes the move was simply caused by an acute situation that demanded more beds in the ICU.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to obtain a deeper understanding of the main concerns in the ICU transitional process as experienced by nurses in intensive care units and general wards in Sweden. Our theory shows a close connection between the nurses' main concern in ICU transitional care—struggling with a gap in a multitude of areas such as communication, technology, staff readiness—and the strategies for diminishing or bridging this gap, sheltering, seeking organizational intertwining, and striving for control.

The gap between the highly technological culture in the ICU and the culture in a general ward may be difficult to reduce totally. Nevertheless, there must be a way to improve and develop care by planning and working out routines; for that, there has to be knowledge of the ICU transitional care process and education for the staff. The goal of medical care should not only be to free up a bed for another patient in need, even if the resources of healthcare institutions are limited. Other authors have observed the gap between ward and ICU transitional care. According to Coyle (2001) the ICU transitional care is influenced by the gap between the ICU and the aftercare at a general ward. Coyle found that the gap is caused by differences in routines, environments, and loss of invasive monitoring, which can cause transfer anxiety without proper preparation and explanation. On the contrary, our study shows that these differences are a consequence of the gap, rather than its cause. A recent literature review (Lin, Chaboyer & Wallis, 2009) showed that intensive care discharge is influenced by organizational factors, individual factors and teamwork factors.

The transition process could be improved by enabling integration through professional meetings, and by creating mutual understanding between staff members in different settings in health care (Lundin, Danielson & Ohrn, 2007). Their findings are similar to ours, highlighting the importance of having strategies on hand for building bridges, and also the need for professional meetings for enabling integration. This sort of intervention should be carried out with knowledge of research into ICU transitional care.

Since 1979, concerned professionals have discussed the possibility of nursing interventions to reduce the stress that the patients meet in the gap between the ICU and the general ward (Schwartz & Brenner, 1979). The nurses in our study are also aware of the importance of connecting these two links in the chain of healthcare—an organizational intertwining—so that the patient receives the best care. However, there seem to be difficulties in the ICU transitional care process that need to be remedied. The nursing staff could be a key group in developing and implementing new procedures in the ICU discharge process (Chiung-Jung Jo & Coyer, 2007). Our study illuminates the nurses' ambiguity as to what extent they are responsible for ICU transitional care and what authority they possess. In spite of this, the study showed very little action towards improvement by the nurses. According to Woodrow (1997) nursing increasingly needs nurses that are highly and actively involved in their practices. The nurses should question and ponder what they are doing. Our study showed that the ward nurses expressed that their workload sometimes was too heavy and that the knowledge of receiving an ICU patient could make them feel overwhelmed. In a study by Hallin and Danielson (2007), the nurses balanced strain and stimulation in their daily work, which contained more stressful work than stimulating work situations. The nurses expressed demands of adaptability, high working capacity, strength and patience so that they could handle every sort of assignments in their profession at a general ward (Hallin & Danielson, 2007). This fact makes it even more important to have routines and strategies that facilitate the nurses' workload in ICU transitional care.

Healthcare is moving towards more patient-centred service, a philosophy of care that emphasizes working across professional and organizational boundaries to support quality service improvements. The improvements are, to a great extent, dependent on the staff's willingness to collaborate in the process (Coombs & Dillon, 2002). Collaboration between physicians and nurses is highly important for the patient and is especially linked to positive outcomes for the patients in the ICU (Stein-Parbury & Liashenko, 2007). Creating a collaborative care culture is needed in functional ICU transitional care. According to Sandberg (2006), to achieve collaborative teamwork, there have to be different kinds of competency in the team, and the team members actually have to collaborate. To reach this point, all team members must act with the knowledge that all members possess important and adequate competencies, and that the solution is mutual giving and taking (Sandberg, 2006). Our theory shows us the importance of collaboration in planning between the team members involved in the care. Feelings and thoughts of hierarchy and status must be minimized; instead, the nurses should view each other as important parts of a chain with different competencies. According to Coombs (2003), teamwork and a collaborative environment require a shared understanding of roles and working practices, but role definitions and power bases, based on traditional and historical boundaries, continue to exist.

The ward nurses expressed frustration and sometimes even anger over how they felt treated when coming to the ICU to receive a patient. Working together as a team in the organization is an important issue to improve the process. According to Sandberg (2006), above all, the competence of the staff in the team influences the working environment. The three aspects of competence in the working environment are professional competence, collaborative competence, and emotional competence (Sandberg, 2006). Knowledge is empowering to those who develop it, those who use it and those who benefit from it (Meleis, Sawyer, Im, Hilfinger Messias & Schumacher, 2000). Also shown in the present study is that knowledge is an important element for collaboration between nurses involved in ICU transitional care. Hence, leaders must take responsibility in the organizations for encouraging and building a collaborative environment and a culture that improves ICU transitional care.

ICU nurses are responsible for assisting the patients in coping with the transfer situation; they also must identify the patients' needs so that an individual discharge plan can be created (Chaboyer, Foster, Kendall & James, 2002). Furthermore, our study shows that the ward nurses also must take early responsibility in planning the transition process. Whittaker and Ball also claims that ward nurses should be part of the process, as they are well suited to minimize the transfer anxiety for the patient (Whittaker & Ball, 2000). If the ward nurses play an early role in the process, the patient and his/her relatives can have their informational needs from the ward fulfilled, and the gap can be reduced. Since the patients had a great need for information when moving from the ICU care to the ward (Strahan & Brown, 2005), the nurses should be able to give this information to the patients and their relatives.

The need for improved communication between the ICU nurses and the ward nurses is important for minimizing risks during ICU transitional care, according to Whittaker and Ball (2000). They describe this lack of functional communication as common, as the ICU nurses fail to adjust the handover information to the ward nurses' needs. They also illuminate the fact that the ward nurses thought that the ICU nurses should dwell on the patients' abilities (i.e. sitting up in the bed), the patients' oral diet, etc. instead of the acuity of the illness. The results in our study showed, furthermore, that the ICU nurses knew that they often used overly medical and technical language, but it was difficult for them not to use the language that they ordinarily employed in the ICU unit.

The healthcare institution should pay attention to the ICU transitional process. The importance of a functional organization is also linked to economic factors. Green and Edmonds (2004) highlight the fact that a malfunctioned discharge process in ICU transitional care (among other things) could lead to the inability for the ICU to accept booked elective-surgery patients. The length of stay (LOS) in the ICU could be prolonged because of the patients' needs for close observation and care that the general ward does not routinely provide. Further, an ICU liaison nurse could provide a more cost-effective, timely, and integrated approach for acute care. This nurse should have responsibilities for coordinating the transitiona l care, being a resource for the junior-based staff, and supporting the ward nurses if and when they provide care for patients with extended needs (Green & Edmonds, 2004).

This study reveals the importance of evidence-based routines in ICU transitional care, and the need to handle the resources with care and prioritise the right choices. To gain knowledge of ICU transitional care, improvements must be carried out, so that the reality of care can afford us with evidence and instruct us in how to refine further our strategies and care. Further, the study also reveals that the nurses find the patients' reactions to a recent transfer to be individual; therefore, individualised care and preparation are needed (c.f. Cutler & Garner, 1995). The routines must consider the individual patients' needs and be patient- centred. Some of the ICU nurses thought that the discharge planning occurred too quickly and that the decisions for transfer were made only over the course of a day. Others experienced quite the contrary; the patient stayed in the ICU at the end of the intensive care period for too long. Both alternatives contributed to ineffective care. The need for transferring at the right time is of importance for the individual patient; for the nurses, so the nurses are able to provide the best care; and for the organization, so that the resources go to those who need them the most. According to Russell (1999), patients are often discharged from the ICU too early, which contributes to a risk for readmission into ICU, since the general wards' resources often are limited. Three main factors contribute to readmissions from the ward: (1) progression of illness; (2) postoperative requirements; and (3) inadequate follow-up care in the general wards. The inadequate follow-up care was often linked to the inability to manage patients with significant health needs (Russell, 1999). Our study observed one way of following up on and crossing these boundaries, when ICU nurses supported the ward nurses, by explaining unfamiliar elements of care.

Having the patient in the ICU for as long as the medical situation warrants is vital for the patients' safety in ICU transitional care. Having confidence in one's own competence is another important factor. Ward nurses need early discharge planning (Whittaker & Ball, 2000) and proper education, support that also could prevent relocation stress for the patients. The nurses' role in planning also has to be clarified, since the nurses actually are responsible for the patients' overall care—not including the medical decisions. In order to increase the capacity of healthcare, and improve the nurses' work situation, it is important to create an educational environment that supports the nurses' needs when new situations among the patients from the ICU arise. This leads to an increased capacity of hospitals' resources, and above all, it will provide safety and wellbeing for the patients and relatives in ICU transitional care.

Methodological discussion

Grounded theory was well suited to describing the main problems for the nurses involved in ICU transitional care. The groups of nurses had both similar and divergent ways of viewing the process, and there were also visible differences between the two hospitals. We began this study by performing focus group interviews, which were interesting, since the informants discussed and described their problems in the process. However, group members all seemed mostly to talk in the same manner and express more or less the same sentiments; the group setting did not always allow an individual to express ideas in another direction. We also sampled individual interviews, which saturated the result.

The researchers have very different experiences concerning intensive care and critically ill patients; these experiences have been used to validate the results. Since the classic version of grounded theory claims that data should speak for itself, these preconceptions have been bridled. Bridling in relation to grounded theory can be seen as a way to hold back preconceptions and see alternative interpretations. Each category should earn its way into the analysis, which means it should be grounded in data rather than rising from the researcher's preconception (Hallberg, 2006). The literature review had been disciplined and restrained before the study in order to optimize the conditions for analysing the data in a neutral way.

Conclusion

The present theory reveals a gap in the care culture between the ICU units and general wards. The main concern in the ICU transitional process was that the nurses were struggling with a gap; therefore, more knowledge about the process is needed in order to minimize the gap. To increase the capacity of healthcare and the nurses' work situation, it is important to create an educational and collaborative environment that supports the nurses' needs to care for the individual patient.

This study will implicate further research in ICU transitional care, with special focus on supporting and preparing the patient to leave the ICU environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors especially wish to thank the participants who shared their thoughts and feelings with us.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ball C. Ensuring a successful discharge from intensive care. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2005;21(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer W., Foster M., Kendall E., James H. ICU nurses' perceptions of discharge planning: A preliminary study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2002;18(2):90–95. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(02)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer W., James H., Kendall M. Transitional care after the intensive care unit: current trends and future directions. Critical Care Nurse. 2005;25(3):16–18. 20–12, 24–16 passim; quiz 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiung-Jung Jo W., Coyer F. Reconsider the transfer of patients from intensive care unit to the ward: A case study approach. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2007;9:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs M., Dillon A. Crossing boundaries, re-defining care: The role of the critical care outreach team. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002;11(3):387–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle M. A. Transfer anxiety: preparing to leave intensive care. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2001;21(1) doi: 10.1054/iccn.2001.1561. 1–4.17(3), 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler L., Garner M. Reducing relocation stress after discharge from the intensive therapy unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 1995;21(1) doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(95)80398-x. 1–4.11(6), 333–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J. M. Focus of nursing in critical and acute care settings: prevention or cure? Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 1997;21(1) doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(97)80921-4. 1–4., 13(3), 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. Theoretical sensitivity: advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Green A., Edmonds L. Bridging the gap between the intensive care unit and general wards-the ICU Liaison Nurse. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2004;21(1) doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2004.02.007. 1–4., 20(3), 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustad L. T., Chaboyer W., Wallis M. ICU patient's transfer anxiety: a prospective cohort study. Australian Critical Care. 2008;21(4):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Smith J., Ball C., Coakley J. Follow-up services and the development of a clinical nurse specialist in intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1997;13(5):243–248. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(97)80374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L. R. M. The core category of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2006;1(3):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin K., Danielson E. Registered nurses' experiences of daily work, a balance between strain and stimulation: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Chaboyer W., Wallis M. A literature review of organizational, individual and teamwork factors contributing to the ICU discharge process. Australian Critical Care. 2009;22(1):29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin C. S., Danielson E., Ohrn I. Handling the transition of adolescents with diabetes: participant observations and interviews with care providers in paediatric and adult diabetes outpatient clinics. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2007;7:e05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney A. A., Deeny P. Leaving the intensive care unit: a phenomenological study of the patients' experience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18(6):320–331. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(02)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis A. I., Sawyer L. M., Im E. O., Hilfinger Messias D. K., Schumacher K. Experiencing transitions: an emerging middle-range theory. ANS Advanced Nursing Science. 2000;23(1):12–28. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell M. The patient's thoughts and feelings about their transfer from intensive care to the general ward. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31(2):322–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. Reducing readmissions to the intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1999;28(5):365–372. doi: 10.1053/hl.1999.v28.a101055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg H. Det goda teamet: om teamarbete, arbetsklimat och samarbetshälsa. The good team: About teamwork, working environment and collaboration health. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. P., Brenner Z. R. Critical care unit transfer: Reducing patient stress through nursing interventions. Heart Lung. 1979;8(3):540–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein-Parbury J., Liashenko J. Understanding collaborating between nurses and physicians as knowledge at work. American Journal of Critical Care. 2007;16(5):470–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahan E. H., Brown R. J. A qualitative study of the experiences of patients following transfer from intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2005;21(3):160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URL 1. Annual report of Swedish Intensive Care. Retrieved January 30, 2009, from http://icuregswe.org%20Annual%20reports/2007/Arsrapport_SIR_2007.pdf.

- Watts R., Gardner H., Pierson J. Factors that enhance or impede critical care nurses' discharge planning practices. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2005;21(5):302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J., Ball C. Discharge from intensive care: a view from the ward. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2000;16(3):135–143. doi: 10.1054/iccn.2000.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibeck V. Fokusgrupper:om fokuserade gruppintervjuer som undersökningsmetod.Focus groups: about focusing group interviews as research method. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow P. Nursing perspectives for intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1997;13(3):151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(97)80889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]