Abstract

A flying insect must travel to find food, mates and sites for oviposition, but for a small animal in a turbulent world this means dealing with frequent unplanned deviations from course. We measured a fly's sensory-motor impulse response to perturbations in optic flow. After an abrupt change in its apparent visual position, a fly generates a compensatory dynamical steering response in the opposite direction. The response dynamics, however, may be influenced by superimposed background velocity generated by the animal's flight direction. Here we show that constant forward velocity has no effect on the steering responses to orthogonal sideslip perturbations, whereas constant parallel sideslip substantially shortens the lags and relaxation times of the linear dynamical responses. This implies that for flies stabilizing in sideslip, the control effort is strongly affected by the direction of background motion.

Keywords: insect vision, velocity, perturbation, dynamical control

1. Introduction

An adult fly spends much of its time flying in search of food, mates and oviposition sites (Chow & Frye 2009). To arrive at a distant target, flies use optic flow generated by their own locomotion to stabilize their heading against perturbations, such as gusts of wind, that might otherwise take them off course (Egelhaaf & Kern 2002). Visual flight stabilization is so important to an adult fly that even small optimizations to successful visual flight control could either improve how frequently resources are obtained, or reduce the energy costs in the process, and thus may have large effects on fitness.

In previous work (Theobald et al. in press) we measured the independent reactions to simulated perturbations in visual position (translations) and orientation (rotations) of tethered Drosophila melanogaster, and found that the visual cues generated by different axes of self-motion (i.e. sideslip, thrust) produced unique dynamical steering responses that were highly predictive of responses to novel stimuli. We estimated these reactions by exposing flies to white noise modulations of perspective-corrected optic flow fields. Although the flies in these experiments viewed visual motion continuously, the net simulated motion was set to zero, such that flies visually ended a trial where they began it. However, in natural situations flies generally progress forwards, or may gradually drift in any direction with a standing breeze. Under such conditions, visual perturbations would be superimposed upon constant velocity ‘background’ motion and might therefore alter the most advantageous responses.

To determine the effect of standing visual velocity on responses to perturbations, we first confirmed the dynamical response to sideslip, a particularly robust optomotor reaction in fruitflies. We then added to the sideslip stimulus a baseline motion field corresponding to simulated constant movement of the fly forwards, backwards or sideways, with respect to a stationary environment. Therefore, from the fly's perspective, the visual scene moves smoothly in one direction (forwards, backwards or sideways) but with unpredictable perturbations to the left and right.

2. Material and methods

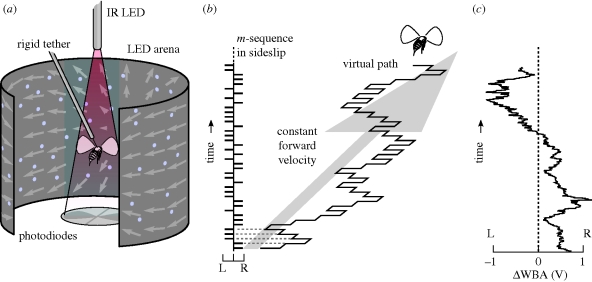

Animal preparation and experimental methods are detailed elsewhere (Theobald et al. in press). Briefly, tethered flies were suspended in a panoramic visual arena consisting 96 × 32 blue light emitting diodes (LEDs), spaced 3.75° apart, and spanning 79 per cent of the complete visual field (Reiser & Dickinson 2008). This allowed fast updates of arbitrary visual scenes in open loop. Flies viewed random dot fields that were animated to simulate perspective-corrected translational motion (figure 1a). This generated a range of spatial and temporal frequencies that mimicked the angular velocities produced during free flight translation. Instantaneous flight steering responses were measured optically as the difference in wing beat amplitude (ΔWBA), which is proportional to yaw torque (Götz 1987; Tammero et al. 2004).

Figure 1.

The experimental set up used to estimate impulse responses. (a) A tethered flying fly centred in the arena, with random dots moving as if the fly were translating forwards. Simultaneously, a pair of photodiodes measures the amplitude of the shadows of the left (L) and right (R) wing beats. IR, infrared. (b) A pseudorandom binary white noise sequence modulates left and right velocities as the fly advances forward, or moves in another direction at constant velocity. (c) An example steering trace, the difference in left and right wing beat amplitudes (ΔWBA) measured in (a) for a single fly during the stimulation depicted in (b).

To measure the steering response to sideslip, we used a correlation technique whereby we modulated sideslip velocities with white noise (in this case an m-sequence (Golomb 1981), figure 1b), then cross-correlated this sequence with the simultaneous responses (Ringach & Shapley 2004). This yields the dynamical linear filter that best links apparent visual velocities with steering (in a purely linear system this is the impulse response, h(t)). The visual effect of white noise modulating image velocity is an unpredictable left–right ‘jitter’ in the visual scene. We added to this stimulus an offset velocity of the same magnitude as the perturbations, but in various directions, to simulate continuous background body drift (figure 1b). A sample steering response to m-sequence modulation of yaw motion is plotted in figure 1c. To estimate to what degree these filters explained actual mean flight responses, we measured a separate group of flies viewing a new m-sequence, averaged their responses, then compared them with predictions generated by convolving the sequences with the previously estimated linear filters and calculated the coefficient of correlation. Forty-seven flies were used to estimate the filters, and 52 flies to estimate mean responses. Each fly was used for only a single experiment, with the four trials presented in a unique, random order. The spatial random dot flow field stimulus was arbitrarily selected from a group of five different random patterns.

3. Results

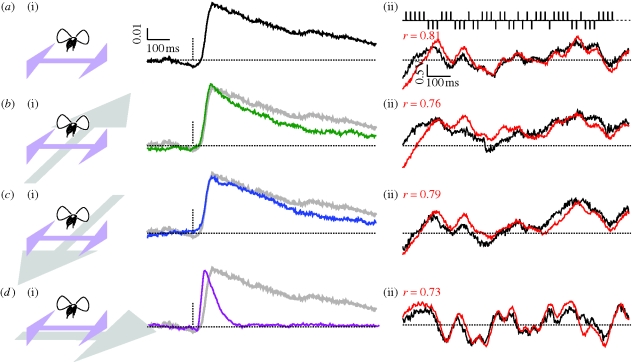

White noise modulation of visual sideslip produces a robust and characteristic impulse response estimate (figure 2a(i)). The time course and shape of the linear filter indicates that wing beat kinematics respond quickly to involuntary changes in sideslip position, with a time to peak response of 92 ms, and work to correct the fly's course against this change. In response to a different white noise sequence, predictions generated by the linear filter account for 66 per cent of the variance produced by flies themselves in response to the same stimulus (figure 2a(ii)).

Figure 2.

Impulse responses to sideslip obtained by cross correlation (n = 47), and mean responses to sideslip (n = 52) compared with linear predictions. (a) A white noise sequence modulated visual sideslip with no additional motion. (i) Shows the estimated linear filter, and (ii) shows 1 s of mean difference in wing beat amplitude in black, and the linear prediction in red, responding to sideslip modulated by the partial m-sequence illustrated above. (b) The same white noise sequence in sideslip with forward motion superimposed. (c) The experiment with backward motion superimposed. (d) The same again, but with perpendicular sideslip motion superimposed.

We next presented perspective-corrected optic flow simulating continuous forward or backward translation, superimposed the white noise sideslip perturbations and calculated the linear sideslip filter. Neither the superposition of forward nor backward translation at two different speeds had any influence on the shape of the sideslip impulse response (figure 2b,c(i)). It follows that neither the linear predictions (convolving the impulse response with the stimulus vector, see figure 2) nor average fly behavioural responses were substantially altered by concomitant orthogonal forward/backward translation motion (figure 2b,c(ii)).

We repeated these experiments, but with the sideslip perturbations now superimposed upon continuous sideslip velocity (rather than forward velocity)—the optic flow field drifted continuously to the left, and was superimposed with white noise modulated sideslip. In contrast to forward translation, continuous sideslip velocity dramatically shortened the delay to onset and relaxation time of the linear filter estimate (figure 2d(i)). The onset delay was shorted to 48 ms, approximately half the value of that obtained without background motion. Accordingly, the new impulse response continues to predict flies’ response to a novel white noise stimulus (figure 2c(ii)).

4. Discussion

White noise methods have been well established for analysing linear and nonlinear properties of biological systems (De Boer & Kuyper 1968; Marmarelis & Naka 1972). Using a rapid white-noise approach in a visual flight simulator, we measure the sensory-motor impulse response of an intact fly to visual sideslip against the background of simultaneous forwards, backwards or sideways translation. The optomotor impulse response does not imply linearity within those mechanisms. Indeed, visual processing contains nonlinearities at several stages. However, the impulse response does provide a robust predictive model that has no free parameters. The predictions then enable precise quantitative assessment of manipulations to the complexity of optic flow such as that experienced under natural conditions.

In free flight, Drosophila generally iterates a sequence of straightforward flight punctuated by rapid turns (Tammero & Dickinson 2002). Therefore, the world continuously translates backwards across the eyes. Fruitflies also orient upwind during flight (Budick & Dickinson 2006), but in anything but purely laminar wind flow, they probably experience substantial sideslip movements. Visual sideslip evokes powerful visual equilibrium wing kinematics (Duistermars et al. 2007) and strong reaction forces and moments (Sugiura & Dickinson 2009).

Our results indicate that (i) the linear impulse response predicts a large fraction of the explainable variation (the variation linked to optic flow) in yaw kinematics during perturbations to sideslip optic flow, and (ii) there appears to be little or no crosstalk between the optomotor control algorithms operating along different axes (figure 2a). This optimal linear filter is highly robust and selective in that it is not influenced at all by superimposed forward velocity (figure 2b). This suggests that compound optic flow stimuli are effectively decomposed into their elemental components, and then in this case only sideslip signals are fed into the stability control algorithm. This interpretation is consistent with the result that sideslip velocity dramatically alters the control of sideslip stabilization. Remarkably, added offset in sideslip velocity improves temporal sensitivity by shortening both the response delay and relaxation time (figure 2c). This result was surprising, because we expected that the background velocity might be perceived as added noise and render the impulse response more sluggish and less correlated with the input stimuli.

In this study we did not consider the effect of rotational velocities, although these might also alter the responses to sideslip. However, rotational saccades comprise vastly less of a flight trajectory than forward translation. Sustained rotation would be experimentally problematic to test for several reasons. It is periodic, bringing the fly back to its original orientation each full rotation cycle, and it alters the direction of wing generated forces with respect to gravity. These issues make standing rotation a more challenging and less relevant stimulus to analyse.

Patterns of optic flow are encoded by wide-field integration neurons of the third optic ganglion in flies (Borst & Haag 2007) that synapse with interneurons projecting into the thoracic motor centres (Haag et al. 2007). Thus, it is probable that these circuits perform critical computations for encoding and decomposing optic flow patterns. Yet, flies exhibit diverse visual behaviours, such as sensitivity to second-order motion, that cannot be readily explained by our current understanding of these circuits (Theobald et al. 2008), and fascinating crossmodal interactions with motion processing and optomotor behaviour have recently been brought to light (Parsons et al. 2006; Chow & Frye 2008).

We are far from achieving a comprehensive model of the control algorithms by which naturalistic patterns of visual motion are integrated into stabilization flight reflexes in these high performance fliers. The linear filters account for most of the mean responses, but there is substantial variation still unexplained, especially in the case of standing sideslip velocity, which may imply static or dynamic nonlinearities. The analyses presented here provide an entry point for further quantitative behavioural, neurophysiological and genetic analyses of the cellular circuits and computational algorithms that bestow flies with visuo-motor robustness and flexibility that have propelled their evolutionary success.

Acknowledgements

M.A.F. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist. This work was funded by NSF grant IOS-0718325 to M.A.F. and NIH EY-12 816 and EY-18 322 to D.L.R.

Footnotes

One contribution to a Special Feature on ‘Control and dynamics of animal movement’.

References

- Borst A., Haag J.2007Optic flow processing in the cockpit of the fly. In Invertebrate neurobiology (eds North G., Greenspan R. J.), pp. 101–122 Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Budick S., Dickinson M. H.2006Free-flight responses of Drosophila melanogaster to attractive odors. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3001–3017 (doi:10.1242/jeb.02305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow D. M., Frye M. A.2008Context dependent olfactory enhanced optomotor flight control in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 2478–2485 (doi:10.1242/jeb.018879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow D. M., Frye M. A.2009The neuro-ecology of resource localization in Drosophila. Fly 3, 50–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer E., Kuyper P.1968Triggered correlation. Biomedical engineering. IEEE Trans. BME 15, 169–179 (doi:10.1109/TBME.1968.4502561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duistermars B. J., Chow D. M., Contro M., Frye M. A.2007The spatial, temporal, and contrast properties of expansion and rotation optomotor responses in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 3218–3227 (doi:10.1242/jeb.007807) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelhaaf M., Kern R.2002Vision in flying insects. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12, 699–706 (doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00390-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb S. W.1981Shift register sequences Laguna Hills, CA: Aegean Park Press [Google Scholar]

- Götz K. G.1987Course-control, metabolism and wing interference during ultralong tethered flight in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 128, 35–46 [Google Scholar]

- Haag J., Wertz A., Borst A.2007Integration of lobula plate output signals by DNOVS2, an identified premotor descending neuron. J. Neurosci. 27, 1992–2000 (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4393-06.2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarelis P. Z., Naka K.1972White-noise analysis of a neuron chain: an application of the Wiener theory. Science 175, 1276–1278 (doi:10.1126/science.175.4027.1276) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. M., Krapp H. G., Laughlin S. B.2006A motion-sensitive neurone responds to signals from the two visual systems of the blowfly, the compound eyes and ocelli. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 4464–4474 (doi:10.1242/jeb.02560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser M. B., Dickinson M. H.2008A modular display system for insect behavioral neuroscience. J. Neurosci. Meth. 167, 127–139 (doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.07.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringach D., Shapley R.2004Reverse correlation in neurophysiology. Cogn. Sci. 28, 147–166 (doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2802_2) [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura H., Dickinson M. H.2009The generation of forces and moments during visually-evoked steering maneuvers in flying Drosophila. PLoS ONE 4, e4883 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammero L. F., Dickinson M. H.2002The influence of visual landscape on the free flight behavior of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 327–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammero L. F., Frye M. A., Dickinson M. H.2004Spatial organization of visuomotor reflexes in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 113–122 (doi:10.1242/jeb.00724) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theobald J. C., Duistermars B. J., Ringach D. L., Frye M. A.2008Flies see second-order motion. Curr. Biol. 18, r464 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theobald J. C., Ringach D. L., Frye M. A.In press Dynamics of optomotor responses in Drosophila to perturbations in optic flow. J. Exp. Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]