Abstract

Diurnal birds belong to one of two classes of colour vision. These are distinguished by the maximum absorbance wavelengths of the SWS1 visual pigment sensitive to violet (VS) and ultraviolet (UVS). Shifts between the classes have been rare events during avian evolution. Gulls (Laridae) are the only shorebirds (Charadriiformes) previously reported to have the UVS type of opsin, but too few species have been sampled to infer that gulls are unique among shorebirds or that Laridae is monomorphic for this trait. We have sequenced the SWS1 opsin gene in a broader sample of species. We confirm that cysteine in the key amino acid position 90, characteristic of the UVS class, has been conserved throughout gull evolution but also that the terns Anous minutus, A. tenuirostris and Gygis alba, and the skimmer Rynchops niger carry this trait. Terns, excluding Anous and Gygis, share the VS conferring serine in position 90 with other shorebirds but it is translated from a codon more similar to that found in UVS shorebirds. The most parsimonious interpretation of these findings, based on a molecular gene tree, is a single VS to UVS shift and a subsequent reversal in one lineage.

Keywords: gulls, UV visual pigment, opsin, phylogeny

1. Introduction

There is a categorical, physiological difference in colour vision between groups of diurnal birds (Cuthill et al. 2000). These have short-wavelength sensitive type 1 (SWS1) cone-opsin-based visual pigments of either an ultraviolet sensitive (UVS) type with maximum absorbance wavelengths (λmax) between 355 and 380 nm or a violet sensitive (VS) type with λmax between 402 and 426 nm (reviewed by Ödeen et al. 2009). The VS type appears to be ancestral (Yokoyama 2002) and phylogenetically most widespread (Ödeen & Håstad 2003) in birds. Independent shifts to UVS may have occurred only three or four times (Håstad et al. 2009): in shorebirds (Charadriiformes), in a common ancestor of passerines and psittaciforms, in Rhea americana and possibly in trogons (Carvalho et al. 2007). Gulls are the only shorebirds reported to be UVS—demonstrated through the presence of cysteine in amino acid (aa) position 90 (bovine rod opsin numbering) in their SWS1 opsin gene and ocular media with spectral transmission similar to that of other UVS birds (Ödeen & Håstad 2003; Håstad et al. 2005, 2009).

There is an increased cost of UV transmittance owing to photo-oxidation of the retina (e.g. Boulton et al. 2001), making the presence of UV tuning in gulls rather puzzling. Unlike other UVS birds, no selective advantage of UV vision has been demonstrated in gulls, whether for detecting sexual signals (e.g. Bennett et al. 1997) or foraging (e.g. Church et al. 1998). It has been suggested to allow eavesdropping on UV communication in schools of fish swimming close to the surface (Ödeen & Håstad 2003) but evidence seems weak. All auks, waders and terns investigated so far have SWS1 opsins of the VS type (Håstad et al. 2005), and some, especially terns, are ecologically similar to gulls. However, too few species have been sampled to safely infer that no other charadriiforms have UV-tuned visual pigments, or that this character state does not vary within Laridae.

The SWS1 λmax pigments in avian retinae closely follows aa sequence variation in the SWS1 opsin gene. In vitro studies have demonstrated that λmax can be predicted on the basis of the opsin's aa sequence (Wilkie et al. 2000; Yokoyama et al. 2000; Carvalho et al. 2007). The cone sensitivity can then be estimated from the opsin sequence, owing to covariance between the visual pigment's λmax and the spectral absorptance properties of the cone oil droplets (Hart & Vorobyev 2005). As spectral tuning of the SWS1 single cone is under direct genetic control, it becomes possible to identify the type of short-wavelength sensitivity in a bird from a sample of genomic DNA. This method was conceived by Ödeen & Håstad (2003) and validated by Ödeen et al. (2009). We have used it here to search for gross differences in colour vision in a significantly widened sample of gulls and other shorebirds. The aim has been to assess how stable the SWS1 pigment sensitivity has been during the evolution of shorebirds in general and gulls in particular. As the basis for this analysis, we have inferred a phylogeny, mainly using GenBank sequence data.

2. Material and methods

We studied a broad selection of species in the order Charadriiformes (table 1) with special emphasis on including a representative sample of various Laridae taxa. We sequenced a fragment of the SWS1 opsin gene containing the aa residues of positions 84–94 in up to six species each of seven shorebird families (table 1). We estimated λmax from three key positions, as outlined by Ödeen et al. (2009).

Table 1.

SWS1 opsin gene fragments from shorebirds. The spectral tuning amino acid (aa) sites 86, 90 and 93 are marked in bold. Type of SWS1 opsin is either VS (violet sensitive) or UVS (UV-sensitive), as predicted from the gene fragment aa sequences. NRM, Swedish Museum of Natural History; LSUMZ, LSU Museum of Natural Science; UWBM, Burke Museum, University of Washington; ZMUC, Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen.

| family | species | common name | aa seq. 84–94 | aa90 codon | type | unknown effect | origin/voucher no. | tissue no. | GenBank acc. no. | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scolopacidae | Tringa glareola | Wood Sandpiper | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | Department of Animal Ecology, U. U. | 031218-2 | GU129664 | this study | |

| Actitis hypoleucos | Common Sandpiper | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY960716 | Håstad et al. (2005) | ||||

| Phalaropus fulicarius | Red Phalarope | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY960718 | Håstad et al. (2005) | ||||

| Gallinago gallinago | Common Snipe | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY960717 | Håstad et al. (2005) | ||||

| Philomachus pugnax | Ruff | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | F. Widemo | 11 individuals | GU129665 | this study | ||

| Thinocoridae | Thinocorus orbignyianus | Grey-breasted Seedsnipe | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | UWBM 54407 | DAB 808 | GU129666 | this study | |

| Laridae | Larus atlanticus | Olrog's Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | P. Yorio, J.-M. Pons | GU129667 | this study | |

| Larus marinus | Great Black-backed Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY227162 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Larus argentatus | European Herring Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY227160 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Larus michahellis | Yellow-legged Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | FJ790325 | Håstad et al. (2009) | |||

| Larus fuscus | Lesser Black-backed Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY227161 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Ichthyaetus hemprichii | Sooty Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY960710 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Leucophaeus pipixcan | Franklin's Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | UWBM 80595 | CSW 6795 | GU129668 | this study | |

| Chroicocephalus hartlaubii | Hartlaub's Gull | FIICVLCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY960709 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Chroicocephalus ridibundus | Black-headed Gull | FIICVLCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY960711 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Rhodostethia rosea | Ross's Gull | FVICVFCISLV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, Leu93 | ZMUC 139640 | GU129669 | this study | ||

| Rissa tridactyla | Black-legged Kittiwake | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | AY960712 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Pagophila eburnea | Ivory Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | ZMUC 132130 | GU129670 | this study | ||

| Xema sabini | Sabine's Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | LSUMZ B-4066 | GU129671 | this study | ||

| Creagrus furcatus | Shallow-tailed Gull | FIICVFCISIV | tgc | UVS | Ile86, 93 | LSUMZ B-15450 | GU129672 | this study | ||

| Rynchopidae | Rynchops niger | Black Skimmer | FVACVFCIFTV | tgc | UVS | LSUMZ B-2457 | GU129673 | this study | ||

| Sternidae | Anous minutus | Black Noddy | FIACIFCIFTV | tgc | UVS | ZMUC 137802 | GU129674 | this study | ||

| Anous tenuirostris | Lesser Noddy | FIACIFCIFTV | tgc | UVS | ZMUC 113339 | GU129675 | this study | |||

| Onychoprion anaethetus | Bridled Tern | FVTCVFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | ZMUC 112708 | GU129676 | this study | ||

| Onychoprion fuscatus | Sooty Tern | FVTCVFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | ZMUC 113320 | GU129677 | this study | ||

| Gygis alba | White Tern | FIACIFCIFTV | tgc | UVS | ZMUC 113340 | GU129678 | this study | |||

| Sternula albifrons | Little Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | NRM 20076398 | GU129679 | this study | ||

| Chlidonias niger | Black Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | NRM 20066936 | GU129680 | this study | ||

| Chlidonias hybrida | Whiskered Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | ZMUC 131916 | GU129681 | this study | ||

| Sterna hirundo | Common Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | Department of Animal Ecology, U. U. | 031218-9 | GU129682 | this study | |

| Thalasseus sandvicensis | Sandwich Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | AY960720 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Sterna paradisaea | Arctic Tern | FVTCIFSIFTV | tcc | VS | Thr86 | AY960719 | Håstad et al. (2005) | |||

| Alcidae | Uria aalge | Common Murre | FLACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY227163 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Alca torda | Razorbill | FVACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY227159 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | ||||

| Stercorariidae | Stercorarius longicaudus | Long-tailed Jaeger | FVACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | NRM 976537 | GU129683 | this study | ||

| Stercorarius parasiticus | Parasitic Jaeger | FVACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | NRM 20066101 | GU129684 | this study | |||

| Stercorarius maccormicki | South Polar Skua | FVACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | ZMUC 131807 | GU129685 | this study | |||

| Glareolidae | Glareola pratincola | Collared Pratincole | FLACVFSVFTV | agc | VS | M. Wilson, A.Ö. | Ug35 | GU129686 | this study | |

| Glareola nuchalis | Rock Pratincole | FLACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | ZMUC 113386 | GU129687 | this study | |||

| Rhinoptilus chalcopterus | Bronze-winged Courser | CLACLFSVFTV | agc | VS | ZMUC 131583 | GU129688 | this study | |||

| Recurvirostridae | Himantopus himantopus | Black-winged Stilt | FVACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY227156 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Haematopodidae | Haematopus ostralegus | Eurasian Oystercatcher | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY227155 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) | |||

| Charadriidae | Pluvialis apricaria | Eurasian Golden Plover | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | Department of Animal Ecology, U. U. | Ljungpipare98 | GU129689 | this study | |

| Charadrius dubius | Little Ringed Plover | FIACIFSVFTV | agc | VS | AY227154 | Ödeen & Håstad (2003) |

For the phylogenetic analyses, we used GenBank sequences of three mitochondrial and three nuclear loci, plus own β fibrinogen (FGB7) and myoglobin sequences of Anous tenuirostris and Gygis alba. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by maximum likelihood for one locus at a time and by Bayesian inference in the following combinations: (i) mitochondrial CO1, ND2 and cytochrome b, (ii) nuclear RAG-1, FGB7 and myoglobin intron 2 (myoglobin), and (iii) all loci together. For details, see the electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

(a). Opsin gene analysis

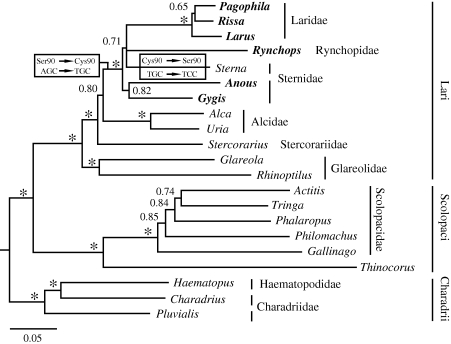

All gull species investigated in this and previous studies (table 1) carry the UVS-pigment-conferring Ser to Cys substitution at aa position 90 (Ser90Cys: Wilkie et al. 2000; Yokoyama et al. 2000), as specified by the codon TGC in the SWS1 opsin gene. We found this trait in four other shorebirds, namely A. minutus, A. tenuirostris, G. alba (Sternidae) and Rynchops niger (Rynchopidae). All other species examined carry Ser90, which is ancestral to Charadriiformes (Ödeen & Håstad 2003; Håstad et al. 2005), but translated from different synonymous codons. In general, VS shorebirds carry AGC; the exception is Sternidae (excluding Anous and Gygis), where all sequences read TCC instead. The distribution of these traits on the phylogeny is shown in figure 1 (and the electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Bayesian inference tree of shorebirds based on mitochondrial ND2, cytochrome b and CO1, and nuclear RAG-1, FGB7 and myoglobin (approx. 7.4 kbp). The species having the UVS-pigment-conferring Ser90Cys substitution in their SWS1 opsin are in bold. The most parsimonious reconstruction of the sequence of mutations in the corresponding codon is shown in boxes. Numbers at nodes are posterior probabilities (values of 1.00 indicated by *). The name of the family Thinocoridae (comprising Thinocorus) is not marked owing to lack of space.

(b). Phylogeny

All analyses produced results largely in agreement with previous studies (Ericson et al. 2003; Paton et al. 2003; Paton & Baker 2006; Baker et al. 2007; Fain & Houde 2007), and identify three main clades corresponding to Lari, Scolopaci and Charadrii. Only the tree based on all loci (figure 1) is shown (combined nuclear and mitochondrial gene trees in the electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2). All trees recover a strongly supported clade comprising Laridae, Sternidae and Rynchops. Within this clade, in the tree based on all loci, Laridae, Rynchops and Sterna form a poorly supported clade, which is sister to an insufficiently supported clade comprising Anous and Gygis. The nuclear tree has the same topology, but even weaker support. In contrast, in the mitochondrial tree, Laridae, Rynchops and Anous form a moderately well-supported trichotomy that is sister to a strongly supported clade containing Gygis as sister to the rest of Sternidae (excluding Anous).

4. Discussion

Our results agree with previous studies in showing that gulls have Cys90 in their SWS1 opsins, characteristic of the UVS class of colour vision. This trait has been conserved during gull evolution, as revealed by the denser taxon sampling of this study compared with previous ones (Håstad et al. 2005). Another new finding is that gulls are not unique among shorebirds in being UVS, as the terns A. minutus, A. tenuirostris and G. alba and the skimmer R. niger share the UVS opsin forming Ser90Cys substitution.

The evolutionary interpretation of our results hinges on the correct inference of the phylogeny. As the relationships in the Laridae/Sternidae/Rynchopidae clade are somewhat uncertain, different interpretations are possible. However, the most parsimonious reconstruction suggests a Ser90Cys substitution in the common ancestor to Laridae/Sternidae/Rynchopidae, and a subsequent reversal to Ser in the Sternidae lineage (except Anous and Gygis), in all formed by two consecutive point mutations in the codon at aa position 90, from AGC to TGC to TCC. This is true even if the uncertainty in the gene tree is taken into account by considering the Sternidae branch (except Anous and Gygis) in alternative positions. For example, the posterior probability that Sterna is outside the clade comprising Laridae, Rynchops, Anous and Gygis—which would support a single Ser90Cys substitution but no subsequent reversal—is lesser than 0.06. Accordingly, our favoured hypothesis based on the available data is a single shift from VS to UVS in the common ancestor to Laridae/Sternidae/Rynchopidae and a subsequent reversal in the Sternidae lineage (except Anous and Gygis).

All key aas we report in positions 86, 90 and 93 have already been described (Wilkie et al. 2000; Yokoyama et al. 2000; Ödeen & Håstad 2003), but the spectral tuning effects of some of them are still unknown. The effect of Cys86 in birds is probably negligible (Ödeen et al. 2009), but neither the effects of Thr86 or Ile86 nor Ile93 has been investigated in vitro. However, the λmax of SWS1 pigment of Anas platyrhynchos, which carries Ile93, is not significantly different from that of species with aas of known effect in this position (Ödeen et al. 2009).

In one aspect, avian colour vision is under simple genetic control: the VS/UVS pigment opsin character depends on the Ser90Cys substitution, which can be caused by a single nucleotide mutation. Still, this character is surprisingly conserved among birds, indicating strong stabilizing selection. This is a rare example of a system where two very similar and well-understood variants of the same gene, which have a significantly different effect on the phenotype and ecology of the carrier, have been equally successful in a large taxon.

Acknowledgements

Tissue and DNA samples were kindly provided by Burke Museum, University of Washington, Seattle; Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen; LSU Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge; Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm; Department of Animal Ecology, Uppsala University; Fredrik Widemo, Jean-Marie Pons and Malcom Wilson. This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas (A.Ö.). Two anonymous reviewers provided constructive criticism, which has improved this paper.

References

- Baker A. J., Pereira S. L., Paton T. A.2007Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of Charadriiformes genera: multigene evidence for the Cretaceous origin of at least 14 clades of shorebirds. Biol. Lett. 3, 205–210 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0606) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A. T. D., Cuthill I. C., Partridge J. C., Lunau K.1997Ultraviolet plumage colors predict mate preferences in starlings. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 8618–8621 (doi:10.1073/pnas.94.16.8618) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M., Rózanowska M., Rózanowski B.2001Retinal photodamage. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 64, 144–161 (doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00227-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L. S., Cowing J. A., Wilkie S. E., Bowmaker J. K., Hunt D. M.2007The molecular evolution of avian ultraviolet- and violet-sensitive visual pigments. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1843–1852 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msm109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church S. C., Bennett A. T. D., Cuthill I. C., Partridge J. C.1998Ultra-violet cues affect the foraging behaviour of blue tits. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 1509–1514 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0465) [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill I. C., Partridge J. C., Bennett A. T. D., Church S. C., Hart N. S., Hunt S.2000Ultraviolet vision in birds. Adv. Stud. Behav. 29, 159–214 (doi:10.1016/S0065-3454(08)60105-9) [Google Scholar]

- Ericson P. G. P., Envall I., Irestedt M., Norman J. A.2003Inter-familial relationships of the shorebirds (Aves: Charadriiformes) based on nuclear DNA sequence data. BMC Evol. Biol. 3, 16 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-3-16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain M. G., Houde P.2007Multilocus perspectives on the monophyly and phylogeny of the order Charadriiformes (Aves). BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 35 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-35) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart N. S., Vorobyev M.2005Modelling oil droplet absorption spectra and spectral sensitivities of bird cone photoreceptors. J. Comp. Physiol. A 191, 381–392 (doi:10.1007/s00359-004-0595-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håstad O., Ernstdotter E., Ödeen A.2005Ultraviolet vision and foraging in dip and plunge diving birds. Biol. Lett. 1, 306–309 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håstad O., Partridge J. C., Ödeen A.2009Ultraviolet photopigment sensitivity and ocular media transmittance in gulls, with an evolutionary perspective. J. Comp. Physiol. A 95, 585–590 (doi:0.1007/s00359-009-0433-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ödeen A., Håstad O.2003Complex distribution of avian color vision systems revealed by sequencing the SWS1 opsin from total DNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 855–861 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msg108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ödeen A., Hart N. S., Håstad O.2009Assessing the use of genomic DNA as a predictor of the maximum absorbance wavelength of avian SWS1 opsin visual pigments. J. Comp. Physiol. A 195, 167–173 (doi:10.1007/s00359-008-0395-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton T. A., Baker A. J.2006Sequences from 14 mitochondrial genes provide a well-supported phylogeny of the Charadriiform birds congruent with the nuclear RAG-1 tree. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39, 657–667 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton T. A., Baker A. J., Groth J. G., Barrowclough G. F.2003RAG-1 sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships within Charadriiform birds. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 268–278 (doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00098-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie S. E., Robinson P. R., Cronin T. W., Poopalasundaram S., Bowmaker J. K., Hunt D. M.2000Spectral tuning of avian violet- and ultraviolet-sensitive visual pigments. Biochemistry 39, 7895–7901 (doi:10.1021/bi992776m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S.2002Molecular evolution of color vision in vertebrates. Gene 300, 69–78 (doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00845-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S., Radlwimmer F. B., Blow N. S.2000Ultraviolet pigments in birds evolved from violet pigments by a single amino acid change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7366–7371 (doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7366) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]