Abstract

Owing to exceptional biomolecule preservation, fossil avian eggshell has been used extensively in geochronology and palaeodietary studies. Here, we show, to our knowledge, for the first time that fossil eggshell is a previously unrecognized source of ancient DNA (aDNA). We describe the successful isolation and amplification of DNA from fossil eggshell up to 19 ka old. aDNA was successfully characterized from eggshell obtained from New Zealand (extinct moa and ducks), Madagascar (extinct elephant birds) and Australia (emu and owl). Our data demonstrate excellent preservation of the nucleic acids, evidenced by retrieval of both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from many of the samples. Using confocal microscopy and quantitative PCR, this study critically evaluates approaches to maximize DNA recovery from powdered eggshell. Our quantitative PCR experiments also demonstrate that moa eggshell has approximately 125 times lower bacterial load than bone, making it a highly suitable substrate for high-throughput sequencing approaches. Importantly, the preservation of DNA in Pleistocene eggshell from Australia and Holocene deposits from Madagascar indicates that eggshell is an excellent substrate for the long-term preservation of DNA in warmer climates. The successful recovery of DNA from this substrate has implications in a number of scientific disciplines; most notably archaeology and palaeontology, where genotypes and/or DNA-based species identifications can add significantly to our understanding of diets, environments, past biodiversity and evolutionary processes.

Keywords: ancient DNA, extinct birds, palaeontology, archaeology, eggshell

1. Introduction

Avian eggshell has been described from numerous fossil deposits and early human settlements all over the world (Miller et al. 1999a, 2005; Dortch 2004; Clarke et al. 2006). Iconic extinct megafauna, such as the New Zealand moa birds (Aves: Dinornithiformes), the elephant birds of Madagascar (two genera: Aepyornis and Mullerornis) and Australian thunderbirds (Genyornis), left behind large amounts of this substrate owing to the sheer size and thickness of their eggs. Fossil eggshells have been used extensively to reconstruct palaeoecology and palaeodiets (Miller et al. 2005; Clarke et al. 2006; Emslie & Patterson 2007), and they also serve as an exceptional medium for a variety of dating methods, including radiocarbon, amino acid racemization and uranium-series disequilibrium (Higham 1994; Johnson et al. 1997; Miller et al. 1999a; Magee et al. 2008).

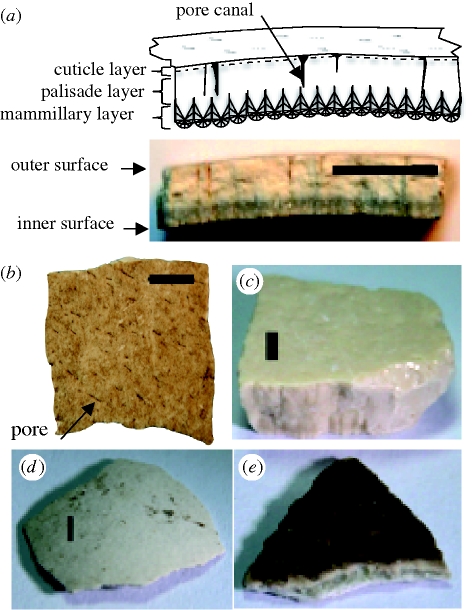

The matrix of avian eggshell is a highly ordered, porous, biomineral, composed of calcium carbonate (calcite, approx. 97%) and an organic matrix (approx. 3%) (Gautron et al. 2001; Nys et al. 2004) (figure 1a) and is formed, along with non-calcified membranes, as the egg passes through the oviduct. The eggshell provides the developing avian embryo with an external skeletal support and aids in protection from physical stress and microbes, and controls the exchange of gases and water (Nys et al. 2004; Wellman-Labadie et al. 2008a). Because most of the organic matrix is intracrystalline, rather than intercrystalline as in most biominerals (Miller et al. 2000), avian eggshell suffers little diffusional loss or isotope exchange of its original organic constituents, and the entry of microbes is largely excluded (Miller et al. 1992; Johnson & Miller 1997). Despite a documented history of biomolecule preservation, the successful retrieval of DNA from fossil avian eggshell has never been described.

Figure 1.

Avian eggshells. (a) Stylized radial cross-section (upper) with corresponding pictorial view (lower) of a moa eggshell (Dinornis robustus). (b) Outer surface of a moa eggshell (D. robustus). Pores are visible and are aligned towards the poles of the egg. (c) Elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus). (d) Duck (Anas sp.). (e) Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). Scale bar, 2 mm.

The past decade has seen the field of ancient DNA (aDNA) diversify from more ‘traditional’ aDNA substrates, such as bone and mummified tissue, into a variety of alternative substrates with varying degrees of success. Some of these include hair and nails; coprolites; sediments (see review, Willerslev & Cooper 2005); feathers (Rawlence et al. 2009). Each of these new substrates presents a unique set of challenges; including variation in the levels of contamination from exogenous DNA, types of DNA damage, presence of PCR inhibitors and the absolute quantity of DNA. To complicate matters further, in the age of high-throughput sequencing (HTS), the degree of microbial contamination is as important as the absolute quantity of endogenous DNA in substrate (Gilbert et al. 2008). For example, a recent study observed that only 45 per cent of the DNA (sequenced using HTS) obtained from a mammoth bone could be aligned to the elephant genome (Poinar et al. 2006). By contrast, Miller et al. (2008) aligned approximately 90 and 58 per cent of HTS sequences using DNA isolated from two mammoth hair extractions (Miller et al. 2008). Clearly, each substrate has a set of variable preservation characteristics that are dependent on many factors, including the depositional environment.

Recently, DNA was extracted from eggshell membranes and other non-shell residues of bird eggs in museum collections and nest sites (Strausberger & Ashley 2001; Bush et al. 2005; Lee & Prys-Jones 2007). However, the only reports of modern DNA being isolated from the eggshell matrix (i.e. without associated membranes) are by Egloff et al. (2009) and Rikimaru & Takahashi (2009), who obtained microsatellite DNA profiles from eggshell ‘powder’ of fresh herring gull (Larus argentatus) (Egloff et al. 2009) and chicken (Gallus gallus) (Rikimaru & Takahashi 2009) eggs. On the basis that amino acids are well preserved in fossil eggshell and given that DNA has been characterized from modern eggshell, we set out to examine the extent of aDNA preservation in fossil eggshell. Furthermore, we critically assess extraction methods and develop a protocol for the efficient isolation and amplification of DNA from this substrate. Our study describes the successful recovery of aDNA from fossil eggshell collected from various archaeological and palaeontological sites in Australia, New Zealand and Madagascar (figure 1 and table 1).

Table 1.

A list of bird eggshell specimens from Australia, Madagascar and New Zealand included in this study, with associated primers and GenBank accession numbers. (The following museum abbreviations are used: WRS, Witchcliffe Rock Shelter; MAD, Madagascar; SPAR, Southern Pacific Archaeological Research; WAM, Western Australian Museum; n.a., not attempted; WA, Western Australia; NSW, New South Wales; SI, South Island; NI, North Island.)

| mtDNA |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| site | specimen ID no. | dates | predicted taxaa | gene | amplicon sizeb (bp) | nuDNA | taxonc, | common name | GenBank no. |

| Australia | |||||||||

| WRSd | WAM T20.5.3A | <400 | Dromaius sp. | 12Se, CRf | 250 | yes | D. novaehollandiae (100%) | emu | GU799584–85 |

| WAM T20.33.6 | 400–700 | Dromaius sp. | 12Sg | 125 | n.a. | D. novaehollandiae (100%) | emu | GU799586 | |

| Tunnel Caved | WAM G10.5B.21 | 13 000 | Dromaius sp. | 12Se, CRf | 250 | yes | D. novaehollandiae (100%) | emu | GU799587–88 |

| WAM G10.106.9 | 19 000 | Dromaius sp. | 12Sg | 125 | no | D. novaehollandiae (100%) | emu | GU799589 | |

| Tallering Hill | WAM_El | — | unknown | 12Se | 250 | yes | Tyto sp. (100%) | owl | GU799590 |

| Popiltahh | M05-A720 | 50 000 | Genyornis | — | no | n.a. | — | ||

| Eurobillih | M00-A110 | 50 000 | Genyornis | — | no | n.a. | — | ||

| Madagascar | |||||||||

| Meandrare Estuary | MAD 95-47 | Holocene | Aepyornis sp. | 12Sg | 125 | n.a. | M. agilis (92%) | elephant bird | GU799600 |

| MAD 95-49 | Holocene | Aepyornis sp. | 12Sg | 125 | n.a. | M. agilis (93%) | elephant bird | GU799601 | |

| Talaky | MAD 97-26 | Holocene | Mullerornis sp. | 12Se | 250 | n.a. | M. agilis (100%) | elephant bird | GU799591 |

| New Zealand | |||||||||

| Pyramid Valley, SI | PV_El | Holocene | unknown | 12Se | 250 | yes | Anas sp. (99%) | dabbling duck | GU799592 |

| Redcliffsi, SI | SPAR 12 | 500–700 | Dinornis sp. | CRj | 250 | no | D. robustus (100%) | SI giant moa | GU799593 |

| Rosslea, SI | RL_El | Holocene | unknown | CRj | 250 | yes | E. crassus (100%) | eastern moa | GU799594 |

| Pounaweak, SI | PN.H18.L.1 | 400–700 | Dinornis sp. | CRj | 250 | yes | D. robustus (99%) | SI giant moa | GU799595 |

| PN.H19.SP2.L1 | 400–700 | Dinornis sp. | CRj | 250 | yes | D. robustus (99%) | SI giant moa | GU799596 | |

| PN.H22.L2 | 400–700 | Dinornis sp. | CRj | 250 | yes | D. robustus (100%) | SI giant moa | GU799597 | |

| Hukanui 7al, NI | H7a_E20 | >3000 | unknown | CRj | 250 | yes | P. mappini (100%) | heavy footed moa | GU799598 |

| Hukanui Pooll, NI | HP_E45 | >3000 | unknown | CRj | 250 | yes | A. didiformis (100%) | little bush moa | GU799599 |

aBased on eggshell morphology and location.

bMaximum amplicon length denoted in italics.

cBased on the closest GenBank BLAST match.

dDates according to Dortch (2004).

emtDNA gene region amplified using primers reported in 12Sa/h; Cooper et al. (2001).

fmtDNA gene region amplified using primers reported in emu CR46F/281R present study.

g12SF5/R4; Haile (2009).

hDates according to Miller et al. (1999b).

iDates according to Jacomb (2009).

jmoa CR262F/441R; Bunce et al. (2003).

kDates according to Hamel (2001).

lDates according to Haile et al. (2007).

2. Material and methods

(a). Materials

Initially, we analysed 18 fossil eggshell fragments from 13 locations in Australia, Madagascar and New Zealand, representing a range of climatic conditions. Eggshells were obtained from both museum collections and directly from excavation sites (table 1; table S1a in the electronic supplementary material) and were selected to provide a full assessment of the quality and extent of preservation of DNA in this substrate. Prior to any DNA-based identification, each eggshell was assigned a morphological species identification based on location and/or thickness of the eggshell. For Dromaius (emu) and Genyornis and the elephant bird eggshells, this was straightforward (Williams 1981), but, because of the range of potential taxa the New Zealand material was unassigned to taxon before DNA sequencing. Where possible, the outermost surfaces of the eggshell were removed by grinding with a Dremel tool (Part no. 114; Racine, WI, USA), to minimize the incorporation of sediments and surface contaminants. Eggshells were then powdered using the same Dremel tool at rotational speeds depending on shell thickness. Powder was collected and weighed in 2.0 ml safelock Eppendorf tubes for later digestion. To prevent contamination from external sources, all samples were prepared in a dedicated aDNA clean room and the sampling area and tools were decontaminated between processing each sample to prevent cross-sample contamination (Cooper & Poinar 2000; Allentoft et al. 2009).

(b). Molecular methods

In our initial study, DNA was extracted from eggshell powder using 66–374 mg by rotational incubation at 55°C for 48–72 h in a 750 µl digestion buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8.0 (Sigma, MO, USA), 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), 1 mg ml−1 proteinase K (Amresco, OH, USA), 0.48 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and 0.1 per cent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Invitrogen)) or (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM DTT, 1 mg ml−1 proteinase K, 0.47 M EDTA and 1 per cent Triton X-100 (Invitrogen)). After centrifugation, the supernatant was concentrated to approximately 50 µl in a Vivaspin 500 column (MWCO 30000; Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Germany) at 13 000 g, and then combined with five volumes of PBi buffer (Qiagen, CA, USA). DNA was extracted using silica spin columns (Qiagen) and cleaned with 700 µl of AW1 and AW2 wash buffers (Qiagen). Finally, the DNA was eluted from the silica in 60 µl of 10 mM of Tris buffer (Qiagen).

DNA samples were initially screened (by PCR) using a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) approximately 250 bp generic bird PCR assay (12Sa/h rRNA) (Cooper et al. 2001). Where DNA preservation was poor, shorter fragments were attempted using a variety of species-specific and generic primers (table 1; table S2 in the electronic supplementary material) (Bunce et al. 2003). Nuclear DNA (nuDNA) was also assessed, where possible, by amplifying a conserved region of the c-mos gene (table S2 in the electronic supplementary material). Multiple negative extraction and amplification controls were included. Selected amplification products were cloned using TOPO TA cloning kits (Invitrogen) and sequenced at a commercial facility, Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea). A subset of samples was sent to Copenhagen and Oxford Universities for independent replication. Sequences were analysed using Geneious 4.8 (Biomatters, New Zealand) and deposited on GenBank (accession numbers GU799584–GU799601).

(c). Optimization of eggshell DNA digestion and extraction methods

Following the successful recovery of DNA from fossil eggshells, different extraction methods were assessed and optimized in order to maximize DNA yields. Eggshells from two moa species in two New Zealand locations, Pounawea (South Island) and Hukanui Pool (North Island), were selected as representative samples. To minimize sample-dependent variation, we used a mixture of eggshell fragments (nine, Anomalopteryx sp. from Hukanui Pool and three, Dinornis sp. from Pounawea (table S1b in the electronic supplementary material)) that were powdered and pooled to provide a bulk sample suitable for a number of controlled DNA extraction methods. In the first comparison, we tested these bulk samples with three slightly modified extraction methods: (i) chelex with proteinase K (CpK); (ii) phenol/chloroform (P/C); and (iii) digest buffer (DBa) (see the electronic supplementary material). Variants of these methods are commonly employed on aDNA substrates (Rohland & Hofreiter 2007b; Allentoft et al. 2009; Schwarz et al. 2009) and recently on modern eggshell (Egloff et al. 2009). To standardize the different extraction methods, the following constants were used: 100 mg of eggshell powder, starting digestion volume 750 µl and final DNA elution in 60 µl.

Following the DBa, chelex and P/C comparisons, we chose the method that generated the highest DNA yield (DBa method) and proceeded with further optimizations of the protocol. To increase solubility, the DBa method was modified by adding a heat step (DBb) at 95°C, following the initial digestion, this modification was included as default in all subsequent extraction optimization tests. The effect of incubation time was investigated by reducing the 55°C digest from 48 to 2 h (DBc). Finally, we compared the effect of surfactant types; we tested both anionic surfactants: 1 per cent SDS (DBd) and non-ionic surfactants: 1 per cent Tween 20 (Sigma) (DBe), 1 per cent Triton X-100 (DBb) in addition to the complete absence (DBf) of surfactants in the DB.

DNA yields were compared using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay and a dilution series (2, 0.5 and 0.125 µl) was performed to test for inhibition effects in assay. Furthermore, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was omitted to allow any inhibition effects to be observed. Two qPCR assays (12Sa/h and CR262F/441R) were performed, in duplicate, using the StepOne real-time PCR system (ABI) in 25 µl reactions containing 2 µl DNA extract, 2X Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI), 10 ρmoles of each primer (table S2 in the electronic supplementary material), and ultrapure H2O. PCR thermal cycling was initiated with a 10 min 95°C denaturation step followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 58°C for 45 s, followed by an extension at 72°C for 10 min. qPCR data were analysed using the StepOne 2.0 software. Cycle threshold values were scored at a consistent baseline and values greater than 37, which could not be accurately quantitated, were given a greater than 40 CT value (tables S3 and S4 in the electronic supplementary material). To determine the relative yield of DNA based on CT values, two quantitative points (CT values which differed according to qPCR conventions) were chosen for each method, normalized to provide an estimated CT value for the undiluted extract and averaged for each PCR assay (see the electronic supplementary material). Student t-tests were performed using SPSS 17.0 (IL, USA) to determine whether modifications to the extraction methods generated significantly different DNA yields.

To assess the total DNA preservation, both endogenous and microbial DNA within eggshell, we compared the relative CT values between avian DNA (12Sa/h) and bacteria (Bac12sqPCR_F and Bac12sqPCR_R) in both eggshell and bone of similar age (table S2 in the electronic supplementary material). Moa bone was isolated according to methods described by Allentoft et al. (2009). PCR reactions were set up as for §2c, with the following modifications; the extension step for 16S was altered to a two-step 60°C, (40 cycle) assay for both primer sets and performed in parallel on a MyiQ Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad).

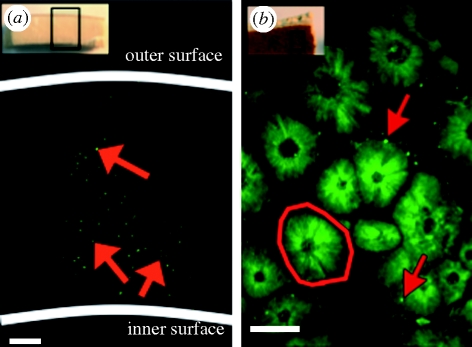

(d). Confocal imaging of DNA in fossil eggshells

With the aim of determining the locality of DNA preserved in the eggshell, we employed confocal microscopy together with fluorescent DNA binding dyes. Moa and elephant bird eggshells (figure 2) were incubated at room temperature in Hoechst 33342 (1 mg ml−1, Invitrogen) and 10X SYBR Green (10 000X nucleic acid stain, Invitrogen) dyes for approximately 15 min, then imaged. Hoechst-stained moa eggshell was imaged using the Bio-Rad MRC 1000/10224 ultra violet confocal microscope using a 40×, NA 1.30 oil immersion objective at 488 nm. SYBR-stained elephant bird eggshell was imaged using the Leica SP2 AOBS multiphoton microscope at 5×, NA 0.15 Fluotar objective and excitation at 488 nm. Optical cross-sectional images were taken and analysed in Image J (Rasband 1997–2009).

Figure 2.

Confocal images of ratite eggshells stained for DNA. (a) Confocal radial cross section of an Aepyornis eggshell, stained with SYBR Green, displaying the DNA distributed throughout the matrix: 5× objective lens, scale bar, 400 µm. Inset, orientation of confocal image. (b) Confocal inner surface of a D. robustus eggshell, stained with Hoechst dye, displaying mammillary cones (outlined) with peripherally located DNA: 40× objective lens, scale bar, 50 µm. Inset, orientation of confocal image. Red arrows, fluorescently labelled DNA.

3. Results and discussion

(a). aDNA is preserved in fossil eggshell

To investigate the level of DNA preservation in fossil eggshell, we sourced samples from a number of palaeontological and archaeological deposits that represent a range of climatic conditions and ages (approx. 400 years to approx. 50 ka old) (table 1; table S1a in the electronic supplementary material). In a set of initial experiments, we attempted to isolate and PCR amplify mtDNA and nuDNA to qualitatively assess biomolecule preservation in these samples. Because there are no existing guidelines on how to maximize DNA recovery from fossil eggshell (see later qPCR data), we employed a methodological approach similar to that used on fossil bone advocated by Rohland & Hofreiter (2007a,b) as the basis for further optimization. We demonstrated that, with the exception of the 50 ka old Genyornis eggshell that failed to amplify, we were able to recover DNA from all eggshell sampled. The recovery of aDNA from the eggshell of the extinct Aepyornis (figure 1c and table 1) is particularly encouraging, as a number of fossil bones from this genus have failed to yield aDNA. The thickness of Aepyornis eggshell readily differentiates it from the smaller Mullerornis, and the similarity of both the Mullerornis and Aepyornis 12S mtDNA sequences to the single published Mullerornis GenBank reference sequence (Cooper et al. 2001) leaves little doubt as to the authenticity of the sequence. In accordance with aDNA guidelines, identical sequences (table 1) were obtained at both the Murdoch and Oxford aDNA facilities (MAD 95-49) (see the electronic supplementary material) (Haile 2009).

New Zealand has experienced numerous avian extinctions since the arrival of Polynesians ca 700 BP, and the eggshell of the giant ratite moa has been found in many former nesting sites, swamps and archaeological deposits. Table 1 describes the successful characterization of moa DNA from five different deposits of Holocene age, in both the North and South Islands. The mtDNA sequences recovered from these eggshell samples can be definitively assigned to moa taxa by comparison with fossil bone mtDNA sequences on GenBank. The recovery of Anas (dabbling duck, Anatidae) DNA from a tiny piece of thin eggshell from the lake sediments at Pyramid Valley (figure 1d and table 1) demonstrates that DNA preservation is not a feature unique to the thick ratite eggshell; even small starting quantities of eggshell matrix can yield authentic mtDNA and nuDNA. The recovery of sequences tentatively assigned to the genus Anas is the first breeding record for that genus from the site (Holdaway & Worthy 1997).

Owing primarily to its hot wet/dry climate, Australia has not traditionally been considered as an environment conducive to long-term DNA preservation (Smith et al. 2003). To test if Pleistocene-aged bird eggshell still contains traces of DNA, we investigated material of that age from two Australian species; the extant Dromaius (figure 1e) and the extinct Genyornis (table 1). We failed to amplify any DNA from Genyornis material which is estimated to be approximately 50 ka old (Miller et al. 1999b), demonstrating that although eggshell may exhibit properties favouring long-term preservation (see later discussion), it is not exempt from ongoing degradation. By contrast, Dromaius eggshell from two limestone cave deposits in southwestern Australia yielded mtDNA and nuDNA sequences from well-dated archaeological contexts up to 19 ka old (table 1) (Dortch 2004). One Dromaius eggshell from an archaeological context was charred (possibly as a result of cooking on coals) but still yielded mtDNA (sample AD211; table S1a in the electronic supplementary material). Again, demonstrating that DNA preservation is not restricted to ratite eggshells, we successfully retrieved DNA from a Holocene owl eggshell (Tallering Hill) and identified it as originating from the genus Tyto (table 1).

Taken together, the DNA sequences from the samples in table 1 indicate that bird eggshell has the potential for long-term DNA preservation in a number of, often hostile, environments that have not traditionally been conducive to long-term DNA survival. With these encouraging findings, we subsequently went on to investigate first the location of DNA in the eggshell matrix, second the efficiency of various DNA extraction methods and finally the ratio of endogenous avian mtDNA to microbial DNA, in eggshell relative to fossil bone. The purpose of these studies was to provide researchers with some foundation data on how to best approach fossil eggshell from a genetic perspective. Approaches that optimize DNA recovery and enrichment are crucial to this field (Rohland & Hofreiter 2007a,b), for example, it now appears somewhat ironic that aDNA researchers (including authors on this paper) (Cooper et al. 2001; Bunce et al. 2003) for years, routinely discarded the supernatant following bone powder de-calcification, when this fraction has subsequently been shown to contain a large proportion of the total DNA in the sample (Schwarz et al. 2009).

(b). Visualizing aDNA in fossil eggshell

The first step in maximizing DNA recovery from eggshell is to determine where the DNA is physically located. In modern eggshell, the membranous layers on the inner surface are often used as a source of DNA—given this, the DNA in fossil eggshell might be located solely on the inner surface as the membranes desiccate onto the matrix. If DNA can be identified as concentrated in the inner, outer or calcified layers of eggshell, it would assist in the development of more efficient sampling strategies. Here, we employed two double-stranded DNA binding dyes and confocal imaging techniques to visualize the DNA in this novel substrate (§2).

Confocal imaging of elephant bird (Aepyornis) eggshell in cross section clearly demonstrated that DNA is distributed throughout the eggshell matrix as evidenced by the presence of fluorescent ‘hot-spots’ (figure 2a). Imaging of the inner surface of moa eggshell (Dinornis) also shows foci of DNA clustered around the edges of mammillary cone structures. These images demonstrate that, at least in ratite eggshell, the preserved DNA is distributed somewhat uniformly throughout the eggshell matrix but may be more concentrated around the periphery of the mammillary cones (figure 2b). Both the size of the DNA ‘hot-spots’ (2–5 µm) and location, even deep in the eggshell (accessed by optical sectioning), are inconsistent with size and shape of bacteria. Bird eggshell consists of approximately 3 per cent organic matter, composed primarily of intracrystalline proteins (Miller et al. 2000) with both structural and antimicrobial functions. One possible hypothesis for the presence of DNA in the eggshell matrix is that when the protein constituents of eggshell are deposited, sloughed epithelial cells are also incorporated into the eggshell calcite (Egloff et al. 2009). Given these findings, we see no clear reason to selectively sample specific parts of the eggshell to maximize DNA recovery, other than the obvious precaution of removing debris from the outer surfaces to minimize microbial load. We argue that the entire eggshell matrix can be powdered and undergo DNA isolation. However, in forensic or conservation case studies where non-destructive sampling is required, filing of the outer eggshell surface, as previously demonstrated (Egloff et al. 2009), may be more appropriate.

(c). Quantitative and qualitative approaches to optimize aDNA recovery from eggshell

The objective of any DNA extraction technique, especially when dealing with low copy number DNA, is to maximize DNA recovery while at the same time minimizing the co-purification of inhibitors, which can impact on the efficacy of polymerases during PCR. Differences in the chemical composition of the substrates often used in aDNA studies (e.g. bone, hair, sediments) mean that extraction methods need to be modified accordingly to maximize DNA recovery. Most modern biological substrates are so rich in DNA that even if an inappropriate DNA isolation method is employed, some amplifiable DNA is still recovered. This is not a luxury afforded by substrates involved in most aDNA studies, especially if low copy number nuDNA sequences are the targets. The ease or difficulty of aDNA research is linked to two primary factors; DNA preservation and DNA extraction efficacy. With this in mind, we set out to compare a number of commonly employed DNA isolation methods using a similar strategy to Rohland & Hofreiter (2007a,b) who compared aDNA recovery from Pleistocene-aged cave bear bones and teeth (Rohland & Hofreiter 2007a,b).

Here, we compared three methods commonly used in the aDNA/forensic literature; chelex resin (with proteinase K), a P/C method commonly employed in aDNA studies reported in the literature (Cooper et al. 2001; Bunce et al. 2003) and last, a DBa in approximately 0.5 M EDTA, which uses a Qiagen silica column (Allentoft et al. 2009). A comparison of the mtDNA recovery was made using two independent qPCR assays (§2). In order to observe the extent of PCR inhibition, a serial dilution was performed in the absence of BSA in order to detect inhibition. By pooling eggshell, replicating qPCR assays and using standardized qPCR chemistry, we have ensured the fidelity and reproducibility of the qPCR data presented in tables 2 and 3. Quantitative data presented in table 2 (and tables S3 and S4 in the electronic supplementary material) clearly demonstrate that chelex and P/C methods are uniformly poor in terms of both DNA recovery and the removal of inhibitors. These results may explain why, using modern eggshell, Egloff et al. (2009) only achieved 68 per cent success using a P/C method and only 29 per cent using chelex. Both of these methods, in our opinion, are highly unsuitable for DNA recovery and could be one reason why aDNA from fossil bird eggshell had not previously been reported.

Table 2.

Results from the qPCR assays comparing three different extraction methods using 100 mg of moa eggshell powder. (CpK, chelex with proteinase K; P/C, phenol chloroform; DBa, digest buffer with Triton X-100; inhibition column: *, ** and *** inhibition observed at neat, 1/4, and 1/16 concentrations, respectively. Relative to best method values are based on normalized CT values (tables S3 and S4 in the electronic supplementary material). CpK and P/C methods both performed statistically worse compared with the best performing method (in bold), DBa (^, p < 0.001).)

| nuDNA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| extraction method | relative to best method | 80 bp | 200 bp | inhibition |

| CpK | <0.01 | yes | no | *** |

| P/C | <0.01 | no | no | *** |

| DBa | 1^ | yes | yes | * |

Table 3.

Results from qPCR assays comparing the initial best performing method from table 2 to the optimized DB extraction methods altering digestion temperature, incubation time and different surfactants using 100 mg of moa eggshell powder. (DB, digest buffer; a, Triton X-100; b, 95°C heat step; c, 2 h incubation; d, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS); e, Tween 20; f, without. DBa performed significantly worse than DBb (*, p < 0.025, paired Students t-test). Incubation time had no significant effect on DNA yield (CT value). Surfactants that performed poorly at a significant level compared with the best performing method (DBd) are indicated by an asterisk (*, p < 0.02 and p < 0.04 for DBe and DBf, respectively (paired Students t-test)). Inhibition column: *, **, inhibition observed at neat and one-quarter concentrations, respectively. Relative to best method values are based on normalized CT values (tables S3 and S4 in the electronic supplementary material).)

| relative to best method |

nuDNA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| digest buffer optimization | Pounawea | Hukanui | average | 80 bp | 200 bp | inhibition | |

| best method in table 2 | DBa | 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.34* | yes | yes | * |

| temperature effect | DBb | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.81 | yes | yes | ** |

| incubation time | DBc | 1 | 0.88 | 0.94 | yes | yes | ** |

| surfactants | |||||||

| SDS | DBd | 0.97 | 1 | 0.99 | yes | yes | ** |

| Tween 20 | DBe | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.36* | yes | yes | ** |

| without | DBf | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.72* | yes | yes | ** |

Table 3 presents qPCR data representing a further optimization of the extraction protocol. In these experiments, we directly compared three variables: (i) the presence/absence of a heating step at 95°C aimed at increasing the solubility of carbonate salts in eggshell, (ii) digest incubation time, and (iii) the effect of different surfactants. The direct comparisons presented in table 3 demonstrate a number of useful ways to maximize recovery. First, the inclusion of a heat step significantly improved DNA recovery (p < 0.025). Second, longer incubation times did not increase DNA yield, in fact approximately 2 h incubations appeared marginally better than longer ones (approx. 48 h), although the difference was not statistically significant. Last, the choice of surfactant also influenced DNA recovery. Tween 20 was always detrimental to recovery (p < 0.02), whereas Triton X-100 and SDS generally outperformed those techniques where surfactants were completely omitted (p < 0.04). However, the increased viscosity of the DB containing SDS made centrifugation through molecular weight cut-off columns time consuming. Of the methods presented in this study to recover DNA from eggshell, we would recommend the use of a DB containing Triton X-100, an incubation time of between 2 and 24 h, followed by a brief heat step at 95°C. A schematic of our suggested DNA isolation approach for fossil bird eggshell can be found in figure S1, electronic supplementary material.

(d). Moa eggshell versus bone: qPCR measures of microbial load

In light of recent advances in DNA sequencing platforms (the Roche GS FLX; ABI SOLiD; Illumina Solexa), and their use in the field of aDNA (Miller et al. 2008; Allentoft et al. 2009), we set out to compare the relative microbial load in moa bone and moa eggshell. These approaches become increasingly important when deciding upon substrates for de novo whole genome sequencing, and marker discovery, where there is normally little interest in sequencing the vast quantities of uncharacterized plant, fungal and bacterial sequences that might have infiltrated specimens post-mortem. Table 4 presents raw qPCR cycle threshold (CT) data for a bird-specific assay (12Sa/h) together with a generic 16S assay that amplifies bacterial DNA. By comparing the ΔCT (the difference in CT values between bird and bacterial assays) values for six bones and six eggshells, there is more (p < 0.003) bacterial DNA present in the moa bone samples compared with moa eggshell. On a cautionary note, although these generic primers have been designed to amplify a wide diversity of bacteria, we cannot rule out biases owing to different depositional environments. The avian to bacterial CT ratios were on average approximately 125 times (or 6.9 PCR cycles) less in eggshell compared with bone (table 4). Ultimately, relative bacterial loads in eggshell need to be calculated by extensive HTS approaches as have been completed for hair, where favourable ratios resulted in this substrate being chosen for the sequencing of the entire mammoth mitochondrial and nuclear genomes (Gilbert et al. 2007; Miller et al. 2008). On the basis of our results, we would suggest that avian eggshell might be a preferable candidate for sequencing extinct avian genomes (mtDNA and nuDNA) including moa, elephant bird, Haast's eagle, the dodo and the great auk, to name a few high profile candidates with interesting evolutionary histories. Alternatively, DNA isolated from feathers might also have similar properties; however, feathers do not preserve as well as eggshell and have to date only been subjected to a limited assessment of aDNA preservation (Rawlence et al. 2009).

Table 4.

A comparison of the relative amounts of moa mtDNA to bacteria DNA in bone and eggshell using qPCR. (Primer sets used in this assay. Samples from Bell Hill and Hukanui are temporarily held by RNH; SPAR, Southern Pacific Archaeological Research.)

| CT values |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| specimen ID no. | excavation site | moa taxon | moa 12Sa | bacteria 16Sb | ΔC*T | mean ΔCT |

| bone | ||||||

| BH_B1 | Bell Hill | D. robustus | 25.64 | 18.62 | 7.02 | 10.38 |

| S39957 | Bell Hill | D. robustus | 25.58 | 18.43 | 7.15 | moa : bacteria 1 : 1333 |

| BH_B2 | Bell Hill | P. elephantopus | 26.53 | 17.23 | 9.3 | |

| SPAR 5 | Redcliffs | E. crassus | 33.60 | 16.11 | 17.50 | |

| SPAR 6 | Redcliffs | E. crassus | 31.81 | 19.67 | 12.14 | |

| SPAR 9 | Redcliffs | E. geranoides | 26.50 | 17.31 | 9.19 | |

| eggshell | ||||||

| PN.J21.L2 | Pounawea | D. robustus | 28.61 | 26.95 | 1.66 | 3.41 |

| PN.H19.SP2.L1 | Pounawea | D. robustus | 28.40 | 26.91 | 1.49 | moa : bacteria 1 : 10.6 |

| PN.H18.L1 | Pounawea | D. robustus | 30.53 | 27.51 | 3.02 | |

| SPAR 12 | Redcliffs | D. robustus | 32.54 | 24.50 | 8.04 | |

| H7a_E20 | Hukanui 7a | P. mappini | 28.44 | 23.27 | 5.17 | |

| HP_E45 | Hukanui Pool | A. didiformis | 23.82 | 22.74 | 1.08 | |

*p < 0.003 (paired Students t-test).

a12Sa/h; Cooper et al. (2001).

bBac16sqPCR_F/Bac16sqPCR_R (present study) CT, cycle threshold.

4. Conclusions

This study provides, to our knowledge, the first evidence that aDNA is preserved in fossil avian eggshell. Using this substrate, we have managed, for the first time, to our knowledge, to obtain authentic, replicated sequences of DNA from the heaviest bird to have ever existed, the extinct elephant bird Aepyornis. The successful retrieval of aDNA from eggshell from Holocene deposits on Madagascar and Pleistocene deposits in Australia is particularly encouraging as neither of these localities have been conducive to long-term DNA preservation in bone. This is most likely owing to a combination of high temperatures and alternating wet/dry cycles. These results raise the question, what properties of eggshell make it conducive to the long-term preservation of biomolecules? We hypothesize that the organic component of eggshell, owing to its stable intracrystalline location, sequesters a small cache of well-preserved DNA as evidenced by the amplification of nuDNA markers (up to 13 ka old) and mtDNA (up to 19 ka old). Bird eggshell is resilient to diffusion losses and acts as a barrier to oxygen and water—the key contributors to aDNA damage via hydrolytic and oxidative mechanisms (Willerslev & Cooper 2005). Interestingly, the organic component of other calcite biominerals, such as mollusc shell, is intercrystalline so different factors may govern biomolecule preservation in these substrates. Modern avian eggshell also exhibits antimicrobial activities (Wellman-Labadie et al. 2008a,b) and it is possible that these remain active in fossil eggshell. The low microbe hypothesis is backed up by qPCR data (table 4), which clearly demonstrates a favourable avian to microbial ratio in moa eggshell when compared with moa bone material of similar age. Excellent mtDNA and nuDNA preservation coupled with low microbial loads make avian eggshell a good candidate for HTS approaches and research is currently underway to identify short tandem repeats markers (Allentoft et al. 2009) and single nucleotide polymorphisms for moa and other species of interest.

In an attempt to make this substrate accessible to researchers in the fields of palaeontology and archaeology, we have undertaken a detailed set of quantitative assessments that aim to maximize the recovery of DNA from fossil eggshell. We demonstrate that through the careful selection of isolation methodology and surfactants, aDNA recovery can be maximized. We would like to echo the thoughts of Rohland & Hofreiter (2007b) data on how best to isolate DNA from biological substrates can have tangible effects on the success or failure of aDNA projects. This study serves as a reminder that all non-mineralized substrates will contain biomolecules of some description, in various states of decay and that systematic descriptions of where DNA is located (figure 2) and how to best isolate it (tables 2 and 3) will facilitate genetic analyses of older, more degraded specimens.

The ability to genetically characterize historic and fossil collections of eggs will benefit a number of research programmes including the study of diets and how they have changed over time, and in response to environmental shifts. For example, Antarctic Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) eggshells up to 38 ka old were recently examined and the δ13C and δ14N isotope values were found to have changed dramatically approximately 200 years ago, prompted by changes in krill availability (Emslie & Patterson 2007). Overlaying both mtDNA and nuDNA genetic signatures (for definitive species and population assignment) together with isotope profiles will assist in data interpretation, particularly in the case of seabird eggshells, which act as a valuable proxy for marine ecosystem health. Clearly, biomolecules preserved in the matrix of historic and fossil eggshell represent a previously unrecognized and untapped source of DNA, the characterization of which will assist in a range of archaeological, palaeontological, conservation and forensic applications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the Western Australian Museum, Canterbury Museum, University of Otago, Palaecol Research and the Musée d'Art et d'Archéologie of the University of d'Antananarivo for their institutional support. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council (DP0771971 and FT0991741), the Marsden Fund of the Royal Society of New Zealand (09-UOO-164 and 06-PAL-001-EEB) and Murdoch University. For confocal imaging, we acknowledge the support of the Australian Microscopy and Microanalysis Research, UWA, funded by UWA and the state and commonwealth Governments. We would also like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy, the British Institute in Eastern Africa, the Danish Natural Science Council, the National Geographic Society, the Natural Environment Research Council, the Nuffield Foundation and the Society of Antiquaries.

References

- Allentoft M., et al. 2009Identification of microsatellites from an extinct moa species using high-throughput (454) sequence data. Biotechniques 46, 195–200 (doi:10.2144/000113086) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce M., Worthy T. H., Ford T., Hoppitt W., Willerslev E., Drummond A., Cooper A.2003Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis. Nature 425, 172–175 (doi:10.1038/nature01871) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K. L., Vinsky M. D., Aldridge C. L., Paszkowski C. A.2005A comparison of sample types varying in invasiveness for use in DNA sex determination in an endangered population of greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Conserv. Genet. 6, 867–870 [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. J., Miller G. H., Fogel M. L., Chivas A. R., Murray-Wallace C. V.2006The amino acid and stable isotope biogeochemistry of elephant bird (Aepyornis) eggshells from southern Madagascar. Q. Sci. Rev. 25, 2343–2356 (doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.02.001) [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A., Poinar H. N.2000Ancient DNA: do it right or not at all. Science 289, 1139 (doi:10.1126/science.289.5482.1139b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A., Lalueza-Fox C., Anderson S., Rambaut A., Austin J., Ward R.2001Complete mitochondrial genome sequences of two extinct moas clarify ratite evolution. Nature 409, 704–707 (doi:10.1038/35055536) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dortch J.2004Palaeo-environmental change and the persistence of human occupation in South-Western Australian forests Oxford, UK: Archaeopress [Google Scholar]

- Egloff C., Labrosse A., Hebert C., Crump D.2009A nondestructive method for obtaining maternal DNA from avian eggshells and its application to embryonic viability determination in herring gulls (Larus argentatus). Mol. Ecol. Res. 9, 19–27 (doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02214.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie S. D., Patterson W. P.2007Abrupt recent shift in δ13C and δ15N values in Adelie penguin eggshell in Antarctica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11 666–11 669 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0608477104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautron J., Hincke M. T., Mann K., Panheleux M., Bain M., McKee M. D., Solomon S. E., Nys Y.2001Ovocalyxin-32, a novel chicken eggshell matrix protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39 243–39 252 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M104543200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M. T., et al. 2007Whole-genome shotgun sequencing of mitochondria from ancient hair shafts. Science 317, 1927–1930 (doi:10.1126/science.1146971) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M. T. P., Miller W., Schuster S. C.2008Response to comment on ‘Whole-genome shotgun sequencing of mitochondria from ancient hair shafts’. Science 322, 857b (doi:10.1126/science.1158565) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile J.2009. Ancient DNA from sediments and associated remains. PhD thesis, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, UK

- Haile J., et al. 2007Ancient DNA chronology within sediment deposits: are paleobiological reconstructions possible and is DNA leaching a factor? Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 982–989 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msm016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel J.2001The archaeology of Otago Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation [Google Scholar]

- Higham T.1994Radiocarbon dating New Zealand prehistory with moa eggshell: some preliminary results. Q. Sci. Rev. 13, 163–169 (doi:10.1016/0277-3791(94)90043-4) [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway R. N., Worthy T. H.1997A reappraisal of the late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of Pyramid Valley Swamp, North Canterbury, New Zealand. New Zeal. J. Zool. 24, 69–121 [Google Scholar]

- Jacomb C.2009Excavations and chronology at the Redcliffs Flat site, Canterbury, New Zealand. Rec. Cant. Mus. 23, 15–30 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J., Miller G. H.1997Archaeological applications of amino acid racemization. Archaeometry 39, 265–287 (doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1997.tb00806.x) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J., Miller G. H., Fogel M. L., Beaumont P. B.1997The determination of the late Quaternary paleoenvironments at Equus Cave, South Africa, using stable isotopes and amino acid racemization in ostrich eggshell. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 136, 121–137 (doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(97)00043-6) [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. L. M., Prys-Jones R. P.2007Extracting DNA from museum bird eggs, and whole genome amplification of archive DNA. Mol. Ecol. Notes 8, 551–560 (doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02042.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee J. W., Miller G. H., Spooner N. A., Questuaux D. G., McCulloch M. T., Clark P. A.2008Evaluating Quaternary dating methods: radiocarbon, U-series, luminescence and amino acid racemisation dates of a late Pleistocene emu egg. Quat. Geochronol. 4, 84–92 (doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2008.10.001) [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Beaumont P. B., Jull A. J. T., Johnson B.1992Pleistocene geochronology and palaeothermometry from protein diagenesis in ostrich eggshells: implications for the evolution of modern humans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 337, 149–157 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0092) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Beaumont P. B., Deacon H. J., Brooks A. S., Hare P. E., Jull A. J. T.1999aEarliest modern humans in southern Africa dated by isoleucine epimerization in ostrich eggshell. Quat. Sci. Rev. 18, 1537–1548 (doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00044-X) [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Magee J. W., Johnson B. J., Fogel M. L., Spooner N. A., Mcculloch M. T., Ayliffe L. K.1999bPleistocene extinction of Genyornis newtoni: human impact on Australian megafauna. Science 283, 205–208 (doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Hart C. P., Roark E. B., Johnson B. J.2000Isoleucine epimerization in eggshells of the flightless Australian birds, Genyornis and Dromaius. In Perspectives in amino acid and protein geochemistry (eds Goodfriend G. A., Collins M. J., Fogel M. L., Macko S. A., Wehmiller J. F.), pp. 161–181 Oxford, MA: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Fogel M. L., Magee J. W., Gagan M. K., Clarke S. J., Johnson B. J.2005Ecosystem collapse in Pleistocene Australia and a human role in megafauna extinction. Science 309, 287–290 (doi:10.1126/science.1111288) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., et al. 2008Sequencing the nuclear genome of the extinct woolly mammoth. Nature 456, 387–390 (doi:10.1038/nature07446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys Y., Gautron J., Garcia-Ruiz J. M., Hincke M.2004Avian eggshell mineralization: biochemical and functional characterization of matrix proteins. C.R. Palevol. 3, 549–562 (doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2004.08.002) [Google Scholar]

- Poinar H. N., et al. 2006Metagenomics to paleogenomics: large-scale sequencing of mammoth DNA. Science 311, 392–394 (doi:10.1126/science.1123360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband W. S.1997–2009Image J Bethesda, MD, USA: US National Institutes of Health; See http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- Rawlence N. J., Wood J. R., Armstrong K. N., Cooper A.2009DNA content and distribution in ancient feathers and potential to reconstruct the plumage of extinct avian taxa. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3395–3402 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0755) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikimaru K., Takahashi H.2009A simple and efficient method for extraction of PCR-amplifiable DNA from chicken eggshells. Anim. Sci. J. 80, 220–223 (doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2008.00624.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohland N., Hofreiter M.2007aAncient DNA extraction from bones and teeth. Nat. Prot. 2, 1756–1762 (doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohland N., Hofreiter M.2007bComparison and optimization of ancient DNA extraction. Biotechniques 42, 343–352 (doi:10.2144/000112383) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz C., Debruyne R., Kuch M., McNally E., Schwarcz H., Aubrey A. D., Bada J., Poinar H.2009New insights from old bones: DNA preservation and degradation in permafrost preserved mammoth remains. Nucl. Acids Res. 37, 3215–3229 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkp159) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. I., Chamberlain A. T., Riley M. S., Stringer C., Collins M. J.2003The thermal history of human fossils and the likelihood of successful DNA amplification. J. Hum. Evol. 45, 203–217 (doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(03)00106-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausberger B. M., Ashley M. V.2001Egg yield nuclear DNA from egg-laying female cowbirds, their embryos and offspring. Conserv. Genet. 2, 385–390 (doi:10.1023/A:1012526315617) [Google Scholar]

- Wellman-Labadie O., Lakshminarayanan R., Hincke M. T.2008aAntimicrobial properties of avian eggshell-specific C-type lectin-like proteins. FEBS Lett. 582, 699–704 (doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman-Labadie O., Picman J., Hincke M.2008bAntimicrobial activity of cuticle and outer eggshell protein extracts room three species of domestic birds. Brit. Poult. Sci. 49, 133–143 (doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willerslev E., Cooper A.2005Ancient DNA. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 3–16 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2813) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. L. G.1981Genyornis eggshell (Dromornithidae: Aves) from the Late Pleistocene of South Australia. Alcheringa 5, 133–140 [Google Scholar]