Abstract

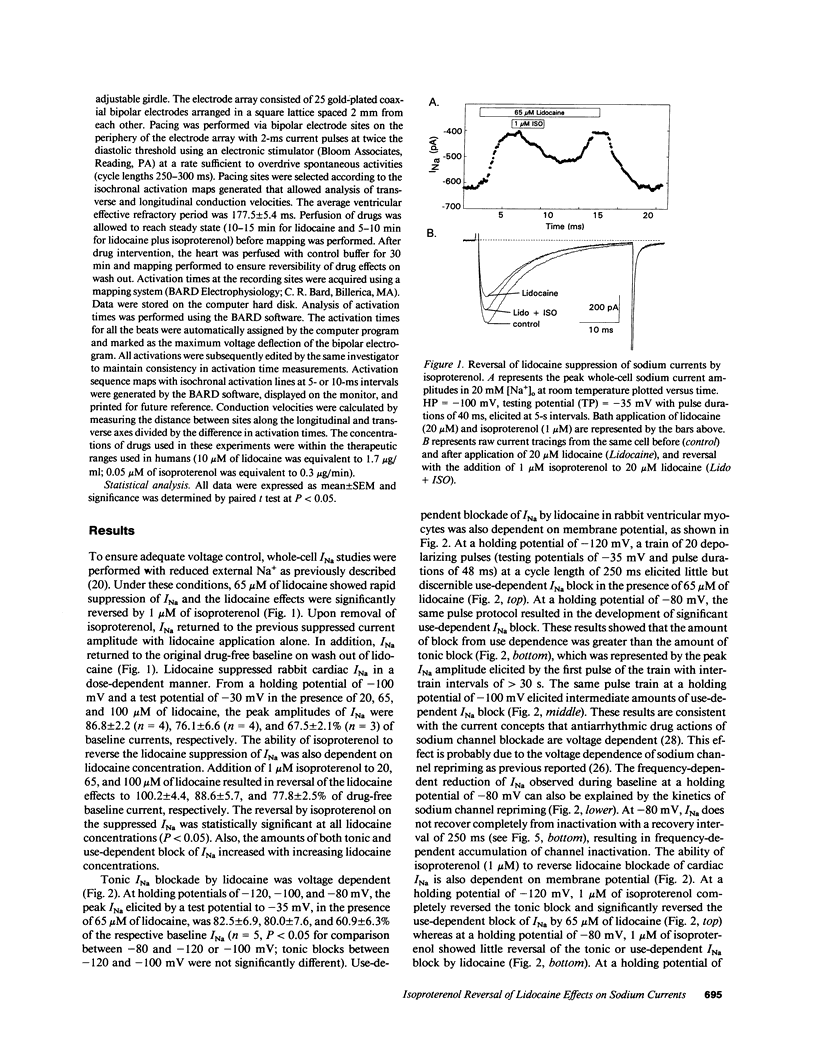

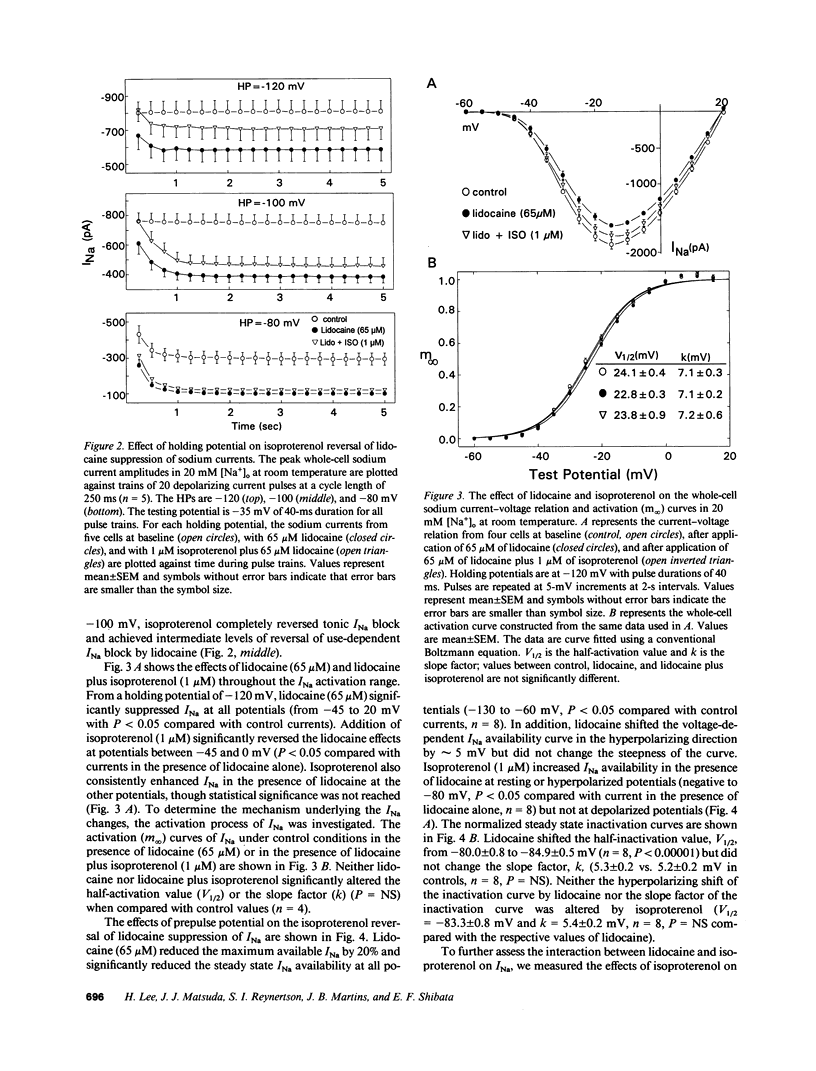

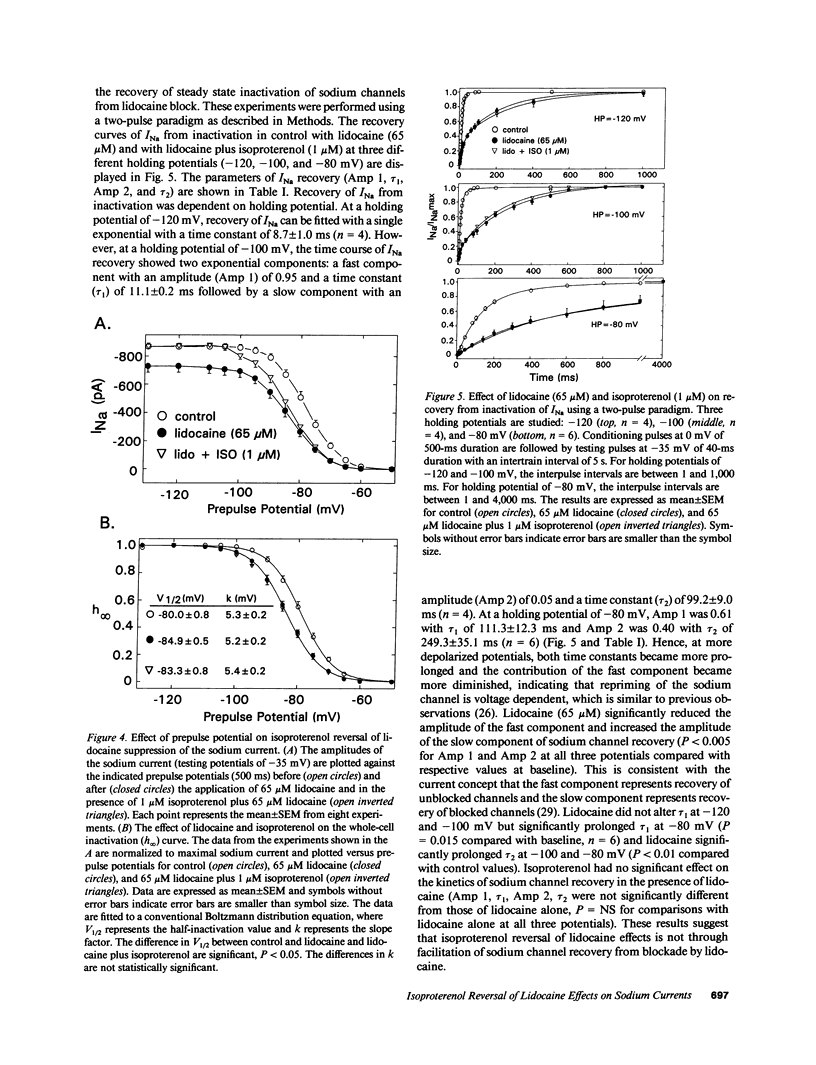

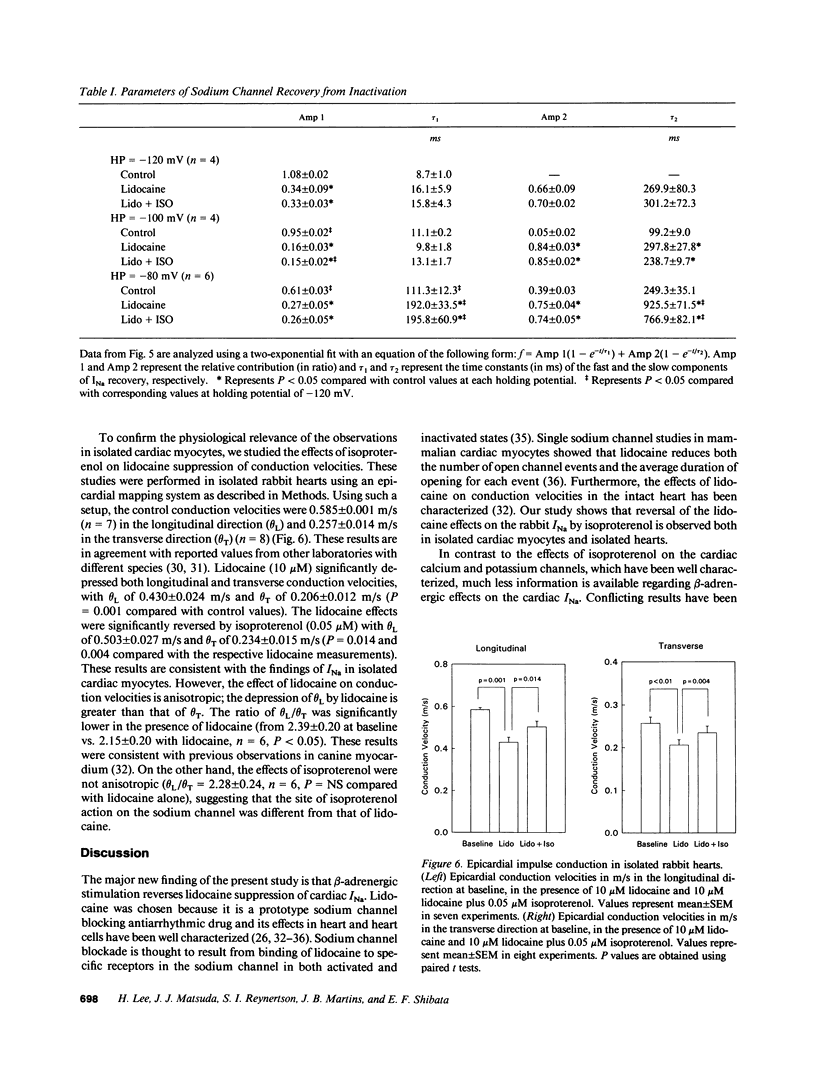

We demonstrated recently that isoproterenol enhanced the cardiac voltage-dependent sodium currents (INa) in rabbit ventricular myocytes through dual G-protein regulatory pathways. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that isoproterenol reverses the sodium channel blocking effects of class I antiarrhythmic drugs through modulation of INa. The experiments were performed in rabbit ventricular myocytes using whole-cell patch-clamp techniques. Reversal of lidocaine suppression of INa by isoproterenol (1 microM) was significant at various concentrations of lidocaine (20, 65, and 100 microM, P < 0.05). The effects of isoproterenol were voltage dependent, showing reversal of INa suppression by lidocaine at normal and hyperpolarized potentials (negative to -80 mV) but not at depolarized potentials. Isoproterenol enhanced sodium channel availability but did not alter the steady state activation or inactivation of INa nor did it improve sodium channel recovery in the presence of lidocaine. The physiological significance of the single cell INa findings were corroborated by measurements of conduction velocities using an epicardial mapping system in isolated rabbit hearts. Lidocaine (10 microM) significantly suppressed epicardial impulse conduction in both longitudinal (theta L, 0.430 +/- 0.024 vs. 0.585 +/- 0.001 m/s at baseline, n = 7, P < 0.001) and transverse (theta T, 0.206 +/- 0.012 vs. 0.257 +/- 0.014 m/s at baseline, n = 8, P < 0.001) directions. Isoproterenol (0.05 microM) significantly reversed the lidocaine effects with theta L of 0.503 +/- 0.027 m/s and theta T of 0.234 +/- 0.015 m/s (P = 0.014 and 0.004 compared with the respective lidocaine measurements). These results suggest that enhancement of INa is an important mechanism by which isoproterenol reverses the effects of class I antiarrhythmic drugs.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson K. P., Walker R., Lux R. L., Ershler P. R., Menlove R., Williams M. R., Krall R., Moddrelle D. Conduction velocity depression and drug-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Effects of lidocaine in the intact canine heart. Circulation. 1990 Mar;81(3):1024–1038. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.3.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahinski A., Nairn A. C., Greengard P., Gadsby D. C. Chloride conductance regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cardiac myocytes. Nature. 1989 Aug 31;340(6236):718–721. doi: 10.1038/340718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean B. P., Cohen C. J., Tsien R. W. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1983 May;81(5):613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett P. B., Woosley R. L., Hondeghem L. M. Competition between lidocaine and one of its metabolites, glycylxylidide, for cardiac sodium channels. Circulation. 1988 Sep;78(3):692–700. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.3.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. B., Giles W. Sodium current in single cells from bullfrog atrium: voltage dependence and ion transfer properties. J Physiol. 1987 Oct;391:235–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson C. W., Follmer C. H., Ten Eick R. E., Hondeghem L. M., Yeh J. Z. Evidence for two components of sodium channel block by lidocaine in isolated cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1988 Nov;63(5):869–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colatsky T. J. Voltage clamp measurements of sodium channel properties in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1980 Aug;305:215–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin L., Kienzle M. G., Brownstein S. L., Martins J. B. Influence of isoproterenol on the left ventricular response to right ventricular extrastimuli. Am J Cardiol. 1989 May 1;63(15):1132–1134. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney K. R. Mechanism of frequency-dependent inhibition of sodium currents in frog myelinated nerve by the lidocaine derivative GEA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975 Nov;195(2):225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra R. C., Winslow E., Pouget J. M., Rahimtoola S. H., Rosen K. M. The effect of isoproterenol on atrioventricular and intraventricular conduction. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Oct;32(5):629–636. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(73)80055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. The cardiac hyperpolarizing-activated current, if. Origins and developments. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1985;46(3):163–183. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(85)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan T. M., Noble D., Noble S. J., Powell T., Twist V. W. An isoprenaline activated sodium-dependent inward current in ventricular myocytes. Nature. 1987 Aug 13;328(6131):634–637. doi: 10.1038/328634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez J. M., Fox A. P., Krasne S. Membrane patches and whole-cell membranes: a comparison of electrical properties in rat clonal pituitary (GH3) cells. J Physiol. 1984 Nov;356:565–585. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R. A., Swerdlow C. D., Echt D. S., Winkle R. A., Soderholm-Difatte V., Mason J. W. Facilitation of ventricular tachyarrhythmia induction by isoproterenol. Am J Cardiol. 1984 Oct 1;54(7):765–770. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friehling T. D., Lipshutz H., Marinchak R. A., Stohler J. L., Kowey P. R. Effectiveness of propranolol added to a type I antiarrhythmic agent for sustained ventricular tachycardia secondary to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Jun 1;65(20):1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91322-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles W., Nakajima T., Ono K., Shibata E. F. Modulation of the delayed rectifier K+ current by isoprenaline in bull-frog atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 1989 Aug;415:233–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A. O., Dietz M. A., Gilliam F. R., 3rd, Starmer C. F. Blockade of cardiac sodium channels by lidocaine. Single-channel analysis. Circ Res. 1989 Nov;65(5):1247–1262. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill O. P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F. J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981 Aug;391(2):85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R. D., Hume J. R. Autonomic regulation of a chloride current in heart. Science. 1989 May 26;244(4907):983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.2543073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M. Antiarrhythmic agents: modulated receptor applications. Circulation. 1987 Mar;75(3):514–520. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri M. R., Van Wyhe G., Avitall B., McKinnie J., Tchou P., Akhtar M. Isoproterenol reversal of antiarrhythmic effects in patients with inducible sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989 Sep;14(3):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimitsuki T., Mitsuiye T., Noma A. Negative shift of cardiac Na+ channel kinetics in cell-attached patch recordings. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jan;258(1 Pt 2):H247–H254. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.1.H247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kléber A. G., Janse M. J., Wilms-Schopmann F. J., Wilde A. A., Coronel R. Changes in conduction velocity during acute ischemia in ventricular myocardium of the isolated porcine heart. Circulation. 1986 Jan;73(1):189–198. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Mohabir R., Smith N., Franz M. R., Clusin W. T. Effect of ischemia on calcium-dependent fluorescence transients in rabbit hearts containing indo 1. Correlation with monophasic action potentials and contraction. Circulation. 1988 Oct;78(4):1047–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe W. F., Podzuweit T., Daries P. S., Opie L. H. The role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in adrenergic effects on ventricular vulnerability to fibrillation in the isolated perfused rat heart. J Clin Invest. 1978 May;61(5):1260–1269. doi: 10.1172/JCI109042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. W., Winkle R. A. Accuracy of the ventricular tachycardia-induction study for predicting long-term efficacy and inefficacy of antiarrhythmic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1980 Nov 6;303(19):1073–1077. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198011063031901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda J. J., Lee H., Shibata E. F. Enhancement of rabbit cardiac sodium channels by beta-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Res. 1992 Jan;70(1):199–207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald T. V., Courtney K. R., Clusin W. T. Use-dependent block of single sodium channels by lidocaine in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 1989 Jun;55(6):1261–1266. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morady F., Kou W. H., Kadish A. H., Nelson S. D., Toivonen L. K., Kushner J. A., Schmaltz S., de Buitleir M. Antagonism of quinidine's electrophysiologic effects by epinephrine in patients with ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Aug;12(2):388–394. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T., Fozzard H. A. Adrenergic modulation of the transient outward current in isolated canine Purkinje cells. Circ Res. 1988 Jan;62(1):162–172. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T., Kodama I., Tsuboi N., Toyama J., Yamada K. Effects of activation sequence and anisotropic cellular geometry on the repolarization phase of action potential of dog ventricular muscles. Circulation. 1987 Jul;76(1):226–236. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C. P., Gettes L. S. Use of isoproterenol as an aid to electric induction of chronic recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 1979 Oct;44(4):705–713. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. Calcium channel modulation by neurotransmitters, enzymes and drugs. Nature. 1983 Feb 17;301(5901):569–574. doi: 10.1038/301569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert B., Vandongen A. M., Kirsch G. E., Brown A. M. Inhibition of cardiac Na+ currents by isoproterenol. Am J Physiol. 1990 Apr;258(4 Pt 2):H977–H982. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach M. S., Dolber P. C., Heidlage J. F., Kootsey J. M., Johnson E. A. Propagating depolarization in anisotropic human and canine cardiac muscle: apparent directional differences in membrane capacitance. A simplified model for selective directional effects of modifying the sodium conductance on Vmax, tau foot, and the propagation safety factor. Circ Res. 1987 Feb;60(2):206–219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat J., Vereecke J., Carmeliet E. A combined study of sodium current and T-type calcium current in isolated cardiac cells. Pflugers Arch. 1990 Oct;417(2):142–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00370691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE A. G., SARNOFF S. J. EFFECTS OF CARDIAC SYMPATHETIC NERVE STIMULATION ON CONDUCTION IN THE HEART. Circ Res. 1964 Jan;14:86–92. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K. B., Begenisich T. B., Kass R. S. Beta-adrenergic modulation of cardiac ion channels. Differential temperature sensitivity of potassium and calcium currents. J Gen Physiol. 1989 May;93(5):841–854. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikswo J. P., Jr, Wisialowski T. A., Altemeier W. A., Balser J. R., Kopelman H. A., Roden D. M. Virtual cathode effects during stimulation of cardiac muscle. Two-dimensional in vivo experiments. Circ Res. 1991 Feb;68(2):513–530. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit A. L., Hoffman B. F., Rosen M. R. Electrophysiology and pharmacology of cardiac arrhythmias. IX. Cardiac electrophysiologic effects of beta adrenergic receptor stimulation and blockade. Part A. Am Heart J. 1975 Oct;90(4):521–533. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woosley R. L., Roden D. M. Pharmacologic causes of arrhythmogenic actions of antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Apr 30;59(11):19E–25E. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P. Proarrhythmic effects of antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Apr 30;59(11):26E–31E. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]