INTRODUCTION

Osteonecrosis of the jaws (ONJ) clinically presents as exposed, necrotic bone in the maxilla or mandible of at least eight week duration, with or without the presence of pain, infection, or previous trauma in a patient who has not received radiation to the jaws (1–3). Although necrotic bone exposure has been reported in the jaws of a variety of patients not receiving bisphosphonates (BPs;4–9), the number of BP related ONJ cases has continued to steadily increase since the first report in 2003 (10). To date, a direct causal relationship between BP use and ONJ has not been established (11,12). However, many retrospective and prospective analyses have identified cases of ONJ where BP therapy, especially the more potent intravenous preparations, was the only consistent variable, strongly suggesting that BPs play a significant role in ONJ pathophysiology (13–24).

Potential mechanisms underlying bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) pathophysiology have generated great debate in the literature (25,26). It is not surprising that many hypotheses attempt to explain the unique localization of BRONJ exclusively to the jaws, including altered bone remodeling, angiogenesis inhibition, constant microtrauma, soft tissue BP toxicity, and bacterial infection (15,18,25,27–29). Importantly, ONJ incidence correlation with BP potency suggests that inhibition of osteoclast function and differentiation might be a key factor in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Currently other inhibitors of osteoclast differentiation and function are entering the pharmacologic armamentarium for the treatment of diseases with increased bone turnover. The association of these new therapies with ONJ is uncertain. We report a case of ONJ in a patient receiving Denosumab, a human RANKL monoclonal antibody currently in clinical trials for the treatment of osteoporosis, primary and metastatic bone cancer, giant cell tumor, and rheumatoid arthritis (30–33).

CASE REPORT

A 65 year-old woman presented to the UCLA School of Dentistry oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic with pain and exposed bone in the posterior mandible of unknown duration. Her medical history was significant for non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, a below the knee amputation for congenitally missing right fibula, hypertension, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia hypothyroidism, and a sacral giant cell tumor (GCT). The GCT was partially resected in 2005. In 2007, the patient fell and suffered an L2-L5 fracture. At this time she was placed on 120 mg of Denosumab subcutaneous injections weekly for three weeks, followed by a two-week holiday, and continued with a single Denosumab 120 mg injection every four weeks as long as she continued to improve. Approximately 2–3 years prior to her visit to our clinic, the patient reported a four month course of 70 mg Alendronate per week “for her bones.”

Her dental history was significant for pain in the posterior right mandible with an onset in late 2008. This resulted in endodontic treatment of the second premolar and first and second molars in the right mandible. In April 2009 at her oncology follow-up, a suspected area of exposed bone in the posterior right mandible was noted. At that time, the patient was referred to UCLA for an oral and maxillofacial surgery consultation.

Upon oral examination, a 4 × 6 mm rectangular area of exposed bone was noted on the lingual surface of the right posterior mandible, 1–2 mm inferior to the gingival margin of the second molar (Fig. 1). There were no signs of infection other than mild erythema surrounding the exposed bone. The area was extremely tender to palpation. The bone surface felt smooth, without sharp edges, and was firmly attached with no clinical evidence of sequestration.

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation of the patient. Exposed bone is seen lingual to tooth #31, with minimal marginal gingival erythema.

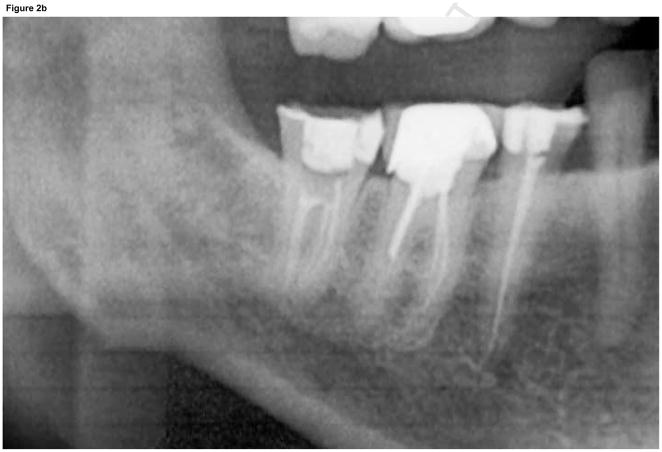

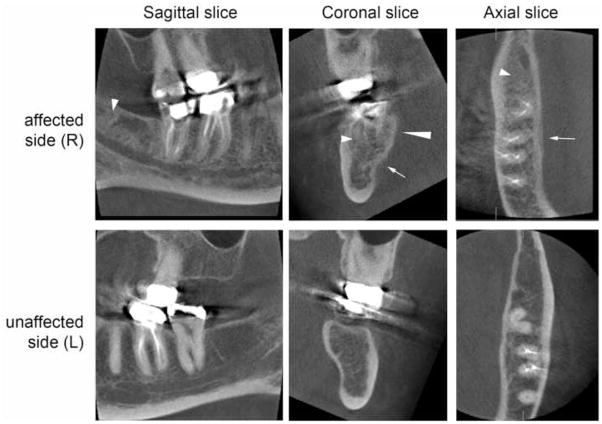

A panoramic radiograph (Fig. 2) revealed irregular trabeculation with increased density at the right retromolar area, extending to the roof of the inferior alveolar canal (IAC). The external oblique ridge and IAC cortication appeared slightly ill-defined. For more detailed evaluation, a limited field of view cone beam CT (CBCT) was performed (Fig. 3). The CBCT confirmed the panoramic findings and furthermore demonstrated slight periosteal new bone formation, irregular cortication of the lingual mandibular plate at the area of #30–32 that corresponded to the area of clinically exposed bone, and irregular trabeculation with increased density throughout the whole buccal-lingual thickness of the mandible from the retromolar area to the area of #30.

Figure 2.

Panoramic radiograph of patient at the time of presentation. A) Panoramic radiograph demonstrates increased trabecular density of posterior right mandible compared to the unaffected left side. B) Magnified view of right posterior mandible demonstrates irregular trabeculation with increased density and loss of cortical definition of the external oblique ridge and roof of the IAC.

Figure 3.

CBCT of the patient. Sagittal (A, D), coronal (B, E), and axial (C, F) slices of the affected (upper panel) and unaffected side (lower panel) demonstrate periosteal bone reaction (arrows), irregular cortication of the lingual mandibular plate (long arrowhead), and increased trabecular density (short arrowheads).

The patient history coupled with the clinical and radiographic findings was consistent with a working diagnosis of ONJ. The disease was classified as Stage 2—exposed and necrotic bone with pain and erythema, without purulent drainage (34). To prevent infection clindamycin 300 mg orally four times per day and chlorhexidine 0.12% mouthrinse twice per day were prescribed. For pain control, Darvon N-100 every 4–6 hours was given. The patient was seen two and four weeks after the initial visit with no change in the clinical severity of exposed bone or erythematous soft tissues.

After eight weeks, the patient represented for follow-up with minimal change in the area of exposed bone, but with slightly more erythematous gingival tissue surrounding the bony exposure. Since the patient now had clinically exposed bone in the mandible for more than eight weeks without a history of radiation therapy, she was diagnosed with ONJ. In this case it was not associated with BP therapy.

Two weeks later, the patient presented to our clinic with a six day history of moderate, erythematous, tender submental swelling causing her difficulty swallowing. No dental or other source of infection was noted. She was admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics and incision and drainage. A CT scan demonstrated localized fluid collection in the submental region. 20–25 cc of purulent fluid was drained from the abscess. While in surgery a thorough oral examination revealed no direct etiology for the submental infection and no connection to the ONJ area. After the surgery, the infection subsided and the patient was discharged.

Several days later, the patient was admitted to a community hospital with symptoms of shortness of breath. A diagnosis of pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure was made. She deteriorated and developed adult respiratory distress syndrome and multi-system organ failure. The patient expired during this hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

Osteonecrosis of the jaws is a complicated disease most commonly associated with BP treatment. Here we report development of ONJ in a patient on Denosumab therapy for the management of a giant cell tumor. Although this patient was medically compromised and on multiple medications, a common thread in ONJ development may be inhibition of osteoclastic activity, mediated in this case by Denosumab.

Osteoclasts are derived from the hematopoietic stem cell lineage, and depend on other cells, such as marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts, to secrete macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and RANKL for their differentiation and function (35). In addition to promoting the fusion of preosteoclasts into osteoclasts, RANKL is required for activation and function of mature osteoclasts (35–37). Vital to the regulation and balance of osteclastogenesis is osteoprotegerin (OPG), an osteoclast decoy receptor that competes with RANK for RANKL binding (38). Together, RANKL and OPG maintain a balance of bone resorption in a healthy state. However, an increase in the RANKL/OPG ratio may shift the balance in favor of bone resorption in skeletal disease (36,39). Since osteoclast mediated bone resorption is pathologic in diseases such as multiple myeloma, metastatic breast and prostate cancer, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and giant cell tumor of bone, inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and function is a primary therapeutic target.

In this case report, Denosumab was utilized to combat osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in a patient with an unresectable sacral GCT. Although GCT is a benign tumor, it may metastasize, undergo malignant transformation, or cause significant skeletal-related events (32). The efficacy of Denosumab in GCT is not surprising, since the tumor contains tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase positive multinucleated giant cells that express osteoclastogenic markers, mononuclear monocytes, and stromal cells (32,40,41). RANKL expression is significantly increased in the stromal cells of GCTs, with a crucial role in its pathogenesis (32,41). BPs such as zoledronic acid have been utilized as adjuvant treatment for GCT with improved symptoms and lower recurrence (42,43), but the specific involvement of RANKL in GCT pathophysiology has contributed to the interest in Denosumab for these patients (32). A current proof-of-principle study demonstrates decreased bone turnover markers, almost elimination of giant cells, reduced pain, and stability of disease in GCT patients without any serious adverse effects (32,44).

BPs, especially nitrogen-containing subset such as zoledronic acid and pamidronate, similarly decrease bone resorption, but through inhibition of farnesyl diphosphate synthetase in the cholesterol biosynthesis mevalonate pathway (45). This leads to osteoclast cytoskeleton disruption, intracellular vesicular trafficking impairment, increased osteoclast apoptosis and decreased osteoclast function (46–53). BPs bind physiochemically to exposed hydroxyapatite (54,55) and incorporate into the bone matrix with a half-life of many years. However unlike BPs, the incorporation and long-term effect of Denosumab on bone remodeling and half-life in the bone matrix are not well defined (31).

Denosumab is a high-affinity, highly specific human IgG2 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds human RANK, and not other members of the TNF ligand superfamily (30,56,57). In clinical trials, Denosumab causes rapid, profound, and prolonged decreases in bone turnover markers without a change in bone formation, suggesting its mostly antiresorptive properties (58–60). Denosumab has also shown excellent clinical results in comparison to BPs in cancer and osteoporosis therapy, with greater increase in bone mineral density and suppression of bone turnover markers (61–63), with efficacy even in patients previously resistant to BPs (33).

Importantly, ONJ has been reported in patients not receiving osteoclast inhibitors. These ONJ cases usually appear in the presence of glucocorticoids, infection, heat induced bone necrosis, trauma, and coagulation disorders (4–9). The patient in this case had a multitude of medical problems including obesity, diabetes, and a short course of alendronate. This complex medical history could have contributed to the outcome of this case and might have impaired bone homeostasis.

We believe that the potent inhibition of osteoclastic activity by Denosumab played a central role in the development of ONJ in this patient. Although the patient reported a history of oral BP use, the short treatment duration is unlikely to have contributed to her ONJ. In a large series of ONJ patients taking alendronate, no cases of BRONJ were reported when the medication was taken for less than three years (64). However, the possibility of alendronate treatment synergistically enhancing Denosumab inhibition of osteoclastic activity and ONJ development should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

We report the development of ONJ in a patient taking Denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody that blocks the binding of RANKL to RANK, therefore inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and function. Although we recognize the many complicated medical factors in this patient, we believe that Denosumab contributed to the ONJ. A recent press release reports equal ONJ incidence for patients treated with Denosumab vs. zoledronic acid for management of bone metastases or multiple myeloma (65). Since osteoclasts are the common target of BPs and Denosumab, potent osteoclast inhibition appears to play a central role in the pathophysiology of ONJ. As more osteoclastic inhibitors enter clinical practice to manage diseases with increased bone turnover, the possibility that these agents might cause ONJ should be investigated ongoing clinical trials will ultimately demonstrate whether an association between Denosumab or other osteoclast inhibitors and ONJ exists.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:753. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shane E, Goldring S, Christakos S, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: more research needed. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1503. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitzman R, Sauter N, Eriksen EF, et al. Critical review: updated recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients--May 2006. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:148. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodmansey KF, White RK, He J. Osteonecrosis related to intraosseous anesthesia: report of a case. J Endod. 2009;35:288. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meer S, Coleman H, Altini M, et al. Mandibular osteomyelitis and tooth exfoliation following zoster-CMV co-infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:70. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pogrel MA, Miller CE. A case of maxillary necrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:489. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah CS, Savage NW. Oral ulceration with bone sequestration. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:61. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glueck CJ, McMahon RE, Bouquot JE, et al. A preliminary pilot study of treatment of thrombophilia and hypofibrinolysis and amelioration of the pain of osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:64. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz HC. Osteonecrosis of the jaws: a complication of cancer chemotherapy. Head Neck Surg. 1982;4:251. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890040313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarassoff P, Csermak K. Avascular necrosis of the jaws: risk factors in metastatic cancer patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1238. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, et al. Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeting ODAC 2005 Package insert revisions re:Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: Zometa injection and Aredia injection.

- 14.Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:527. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortensen M, Lawson W, Montazem A. Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with bisphosphonate use: Presentation of seven cases and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000240885.64568.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zervas K, Verrou E, Teleioudis Z, et al. Incidence, risk factors and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma: a single-centre experience in 303 patients. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagan JV, Murillo J, Jimenez Y, et al. Avascular jaw osteonecrosis in association with cancer chemotherapy: series of 10 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:120. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke BM, Boyette J, Vural E, et al. Bisphosphonates and jaw osteonecrosis: the UAMS experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:396. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durie BG, Katz M, Crowley J. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200507073530120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khamaisi M, Regev E, Yarom N, et al. Possible association between diabetes and bisphosphonate-related jaw osteonecrosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1172. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pozzi S, Marcheselli R, Sacchi S, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of 35 cases and an evaluation of its frequency in multiple myeloma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:56. doi: 10.1080/10428190600977690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey AB. Is bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw caused by soft tissue toxicity? Bone. 2007;41:318. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen MR, Burr DB. The pathogenesis of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: so many hypotheses, so few data. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:61. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood J, Bonjean K, Ruetz S, et al. Novel antiangiogenic effects of the bisphosphonate compound zoledronic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1055. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrotra B, Ruggiero S. Bisphosphonate complications including osteonecrosis of the jaw. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006;356 doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruggiero SL, Fantasia J, Carlson E. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: background and guidelines for diagnosis, staging and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:433. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geusens P. Emerging treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis - focus on denosumab. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:241. doi: 10.2147/cia.s3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewiecki EM. Denosumab update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:369. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832ca41c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas DM, Skubitz KM. Giant cell tumour of bone. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:338. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832c951d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fizazi K, Lipton A, Mariette X, et al. Randomized phase II trial of denosumab in patients with bone metastases from prostate cancer, breast cancer, or other neoplasms after intravenous bisphosphonates. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws--2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baud’huin M, Lamoureux F, Duplomb L, et al. RANKL, RANK, osteoprotegerin: key partners of osteoimmunology and vascular diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2334. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7104-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tat SK, Padrines M, Theoleyre S, et al. OPG/membranous--RANKL complex is internalized via the clathrin pathway before a lysosomal and a proteasomal degradation. Bone. 2006;39:706. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofbauer LC, Heufelder AE. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin in bone cell biology. J Mol Med. 2001;79:243. doi: 10.1007/s001090100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan T, Atkins GJ, Trivett MK, et al. Molecular profiling of giant cell tumor of bone and the osteoclastic localization of ligand for receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:117. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62959-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimoto N, Nakagawa K, Seichi A, et al. A new bisphosphonate treatment option for giant cell tumors. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:643. doi: 10.3892/or.8.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tse LF, Wong KC, Kumta SM, et al. Bisphosphonates reduce local recurrence in extremity giant cell tumor of bone: a case-control study. Bone. 2008;42:68. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas D, Chawla S, Skubitz K, et al. Denosumab treatment of giant cell tumor of bone: interim analysis of an open-label phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:10500. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shipman CM, Rogers MJ, Apperley JF, et al. Bisphosphonates induce apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines: a novel anti-tumour activity. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2713086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami H, Takahashi N, Sasaki T, et al. A possible mechanism of the specific action of bisphosphonates on osteoclasts: tiludronate preferentially affects polarized osteoclasts having ruffled borders. Bone. 1995;17:137. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(95)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes DE, Wright KR, Uy HL, et al. Bisphosphonates promote apoptosis in murine osteoclasts in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1478. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sato M, Grasser W. Effects of bisphosphonates on isolated rat osteoclasts as examined by reflected light microscopy. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:31. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogers MJ, Gordon S, Benford HL, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Cancer. 2000;88:2961. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12+<2961::aid-cncr12>3.3.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogers MJ. From molds and macrophages to mevalonate: a decade of progress in understanding the molecular mode of action of bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75:451. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luckman SP, Hughes DE, Coxon FP, et al. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates inhibit the mevalonate pathway and prevent post-translational prenylation of GTP-binding proteins, including Ras. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:581. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coxon FP, Helfrich MH, Van’t Hof R, et al. Protein geranylgeranylation is required for osteoclast formation, function, and survival: inhibition by bisphosphonates and GGTI-298. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1467. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zerial M, Stenmark H. Rab GTPases in vesicular transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:613. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90130-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato M, Grasser W, Endo N, et al. Bisphosphonate action. Alendronate localization in rat bone and effects on osteoclast ultrastructure. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:2095. doi: 10.1172/JCI115539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jung A, Bisaz S, Fleisch H. The binding of pyrophosphate and two diphosphonates by hydroxyapatite crystals. Calcif Tissue Res. 1973;11:269. doi: 10.1007/BF02547227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reddy GK, Mughal TI, Roodman GD. Novel approaches in the management of myeloma-related skeletal complications. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;4:15. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2006.n.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romas E. Clinical applications of RANK-ligand inhibition. Intern Med J. 2009;39:110. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bekker PJ, Holloway DL, Rasmussen AS, et al. A single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG 162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1059. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McClung MR, Lewiecki EM, Cohen SB, et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Body JJ, Facon T, Coleman RE, et al. A study of the biological receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand inhibitor, denosumab, in patients with multiple myeloma or bone metastases from breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1221. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown JP, Prince RL, Deal C, et al. Comparison of the effect of denosumab and alendronate on BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:153. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0809010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, et al. Randomized active-controlled phase II study of denosumab efficacy and safety in patients with breast cancer-related bone metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4431. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, et al. Extended efficacy and safety of denosumab in breast cancer patients with bone metastases not receiving prior bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6690. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marx RE, Cillo JE, Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2397. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amgen. 2009 www.amgen.com/media/media_pr_detail.jsp?releaseID=1316081.