Introduction

As of 2007, it was estimated that the rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in West and Central Africa had resulted in 430 000 patients with advanced HIV disease receiving treatment of a total in need of 1.7 million [1]. Although the prevalence seems to be declining [2-4], West Africa remains the epicentre of the HIV-2 epidemic. Compared to HIV-1, HIV-2 infection is characterised by a longer latency period [5] and a slower T Lymphocyte CD4+ (CD4) depletion with a lower plasma viral load [6, 7], but nonetheless leads to clinical AIDS in some instances [8, 9]. Unfortunately data on the ART response in HIV-2 and dually positive patients are sparse [10-19]. There is clear evidence that non nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) are inappropriate for the treatment of HIV-2 infection [20]. However, this type of regimen remains the first line treatment of choice in resource-limited countries [1]. Even where a protease inhibitor (PI) regimen has been used results have not always been encouraging [12, 14], perhaps due to HIV-2 having a decreased susceptibility to several, especially unboosted PIs, [21] or to the presence of viral resistance mutations prior to the onset of an effective PI-based therapy [13, 15, 22-25]. In Abidjan, a lower CD4 response at six months has been reported in HIV-2 and dually positive patients compared to HIV-1 infected patients [26].

In this context of a rapid scale-up of ART delivery, a consortium of leading clinicians and clinical epidemiologists from five major cities around West Africa, representing 11 adult clinic cohorts has been assembled in West Africa in the context of the global International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) Collaboration of the US National Institutes of Health [27, 28]. Using this international database, we describe the case management of HIV-2 infected or dually positive patients and their response to treatment compared to HIV-1 infected patients in West Africa.

Methods

Patients

The IeDEA ([27]) in West Africa is a prospective, observational multi-cohort collaboration, established since 2006, assembling data from 11 cohorts of HIV-infected adult patients in Benin [29], Gambia [5], Côte d’Ivoire [26], Mali [30] and Senegal [31, 32]. For the present study, we selected all patients aged 16 or older at ART initiation with a documented date of starting ART, HIV type, and at least one measure of CD4 count during the first year of follow-up [33]. For the main analysis comparing NNRTI and PI-containing regimens, patients treated by triple nucleoside combinations and other regimens were considered in a third category. The IeDEA West Africa collaboration protocol was approved by the national ethics committees of each country and each clinical site has Federal Wide Assurance (FWA) number identification.

Biological assays

In Côte d’Ivoire, the standard serologic testing algorithm for primary care centres consists in a series of two rapid HIV assays, the Determine HIV-1/HIV-2 (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA), followed by the Genie II HIV-1/HIV-2 (Bio-Rad laboratories, Marne-La-Coquette, France) [34]. The first test used for screening was the same in all countries but in Gambia where the Murex test was used (Abbott Laboratories). The second test was ImmunoComb II HIV 1 & 2 BiSpot (Orgenics Ltd, Israel) for Mali and Senegal, Hexagon HIV (Human, Wiesbaden, Germany) in Gambia. A third test based on Genie II in Mali, ImmunoComb II in Benin or Pepti-lav 1-2 assay (Bio-Rad) in Gambia could be performed in case of discrepancy between the first two test results.

Statistical analyses

The date of initiation of ART was considered as baseline. Analyses were performed on intent-to-treat basis. The change of CD4 absolute count after treatment initiation was analysed using piecewise linear mixed models that take into account correlation of measurements within each patient. The dynamics of CD4 response was modelled with two slopes: before and after three months. This change was estimated using a profile-likelihood and was in agreement with previously published results [14, 35]. The effect of any covariate on each average slope was assessed using a Wald test. Robustness of the results was checked after square root transformation of the CD4 [36]. Loss to follow-up was assumed in patients who were not known to have died and who were not seen for at least one year before closing the database for the present analysis. Potential bias due to informative drop-out was checked by comparing these estimates with those from a joint model of longitudinal measurements of CD4 and log time to drop-out [37]. As results were very robust, we are not reporting this latter analysis (available from the authors).

Results

Study population characteristics

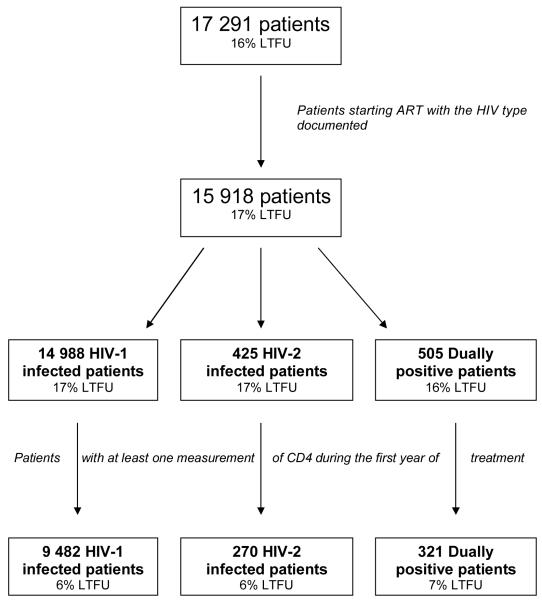

Among 17 291 patients, including 16% lost to follow-up (LTFU), 10 073 were eligible for this analysis, including 6% LTFU (Figure 1). Excluded patients (N=7 218) presented similar baseline characteristics (gender, age, CD4, ART regimen and previous exposure to antiretrovirals) compared to included patients. There were similar rates of patients LTFU in included and excluded patients according to HIV type (p=0.26). In the present sample, 9 482 patients were infected by HIV-1 only, 270 by HIV-2 only and 321 by both types of virus (dually positive patients). Patient characteristics according to the type of infection are reported in Table 1. Patients started combined antiretroviral therapy between 1997 and 2007 (85% between 2004 and 2007). More than three-quarter (N=7 894, 78%) of the patients were treated by a NNRTI-based regimen. The most common combinations were d4T+3TC+nevirapine (29%), d4T+3TC+efavirenz (22%) and AZT+3TC+efavirenz (19%). Among PI-containing regimens (N=1 616), the most common combinations were AZT+3TC+indinavir (22%), d4T+3TC+indinavir (15%) and AZT+3TC+nelfinavir (11%). Few patients (N=470) were treated with a ritonavir-boosted regimen. The remaining other regimens (N=563) included AZT+3TC+abacavir (43%) and d4T+3TC+ddI (8%). There were 544 (5.4%) patients who switched a major drug of their regimen (PI, NNRTI or Abacavir) during the first 12 months. The median time to switch was 4 months (IQR= 2; 8). Among patients treated with an NNRTI-containing regimen, more HIV-2 and dually positive patients changed to a PI-containing regimen compared to HIV-1 patients (p<.001). A total of 322 patients switched for a PI-containing regimen: 299 were HIV-1 infected patients (4% of those treated with NNRTI), nine were HIV-2 infected patients (20% of those treated with NNRTI) and 14 were dually positive patients (10% of those treated with NNRTI). The time of changing since ART initiation was not significantly different according to the HIV-type (3, 4 and 5 months, respectively for HIV-1, HIV-2 and dually positive patients).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the selection of patients. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration.

LTFU: Lost to follow-up in the first year after treatment initiation (see definition in the methods)

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by HIV type. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration, 1997-2007 (N=10 073).

| Type of infection |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | HIV-2 | Dually positive |

p-value | Overall | |

| Total N (%) | 9482 (100) |

270 (100) |

321 (100) |

10073 (100) |

|

| Baselinea characteristics | |||||

| Gender | <10−4 | ||||

| Women (%) | 6071 (67) | 147 (54) | 166 (52) | 6384 (63) | |

| Median age (IQR) |

37 (31-43) |

43 (36-50) |

40 (23-46) |

<10−4 | 37 (31-44) |

| Advanced clinical stage of AIDS diseaseb |

0.16 | ||||

| Yes (%) | 4114 (43) | 97 (36) | 141 (44) | 4352 (43) | |

| No (%) | 3685 (39) | 123 (46) | 123 (38) | 3931 (39) | |

| Unknown (%) | 1683 (18) | 50 (18) | 57 (18) | 1790 (18) | |

| Previous exposure to antiretrovirals | <10−4 | ||||

| Yes (%) | 894 (9) | 31 (11) | 31 (10) | 956 (9) | |

| No (%) | 8174 (86) | 199 (74) | 283 (88) | 8656 (86) | |

| Unknown (%) | 414 (5) | 40 (15) | 7 (2) | 461 (5) | |

| Type of regimen | <10−4 | ||||

| 2NRTIs+1NNRTI (%) | 7714 (81) | 45 (17) | 135 (42) | 7894 (78) | |

| 2NRTIs+1PI (%) | 931 (10) | 109 (40) | 106 (33) | 1146 (11) | |

| 2NRTIs+1 boosted PI(%) | 326 (3) | 84 (31) | 60 (19) | 470 (5) | |

| 3NRTIs (%) | 325 (3) | 21 (8) | 15 (5) | 361 (4) | |

| Others (%) | 186 (2) | 11 (4) | 5 (1) | 202 (2) | |

| Patients with CD4 count at baseline (%) | 8824 (93) | 270 (100) | 306 (95) | <10−4 | 9400 (93) |

| Median CD4 (IQR) | 155 (68-250) |

148 (77-232) |

152 (69-236) |

0.52 | 155 (68-249) |

| Follow-up characteristics | |||||

| Median number of CD4 measurements including baseline (IQR) |

2 (1-2) |

2 (1-3) |

2 (1-2) |

0.16 | 2 (1-2) |

| Median follow-up in months (IQR) | 11 (7-12) |

11 (6-13) |

11 (7-12) |

0.33 | 11 (7-12) |

| Patients lost-of-follow-up (%) | 586 (6) | 16 (6) | 24 (7) | 0.63 | 626 (6) |

| Patients died (%) | 114 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.84 | 122 (1) |

IQR: InterQuartile Range, NRTI: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, NNRTI: Non Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor, PI: Protease Inhibitor

Baseline: initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy

Advanced clinical stage defined according to Centers for Disease Control (CDC) classification (stage C AIDS) or World Health Organization (WHO) classification (stage 3 or 4)

CD4 response to treatment

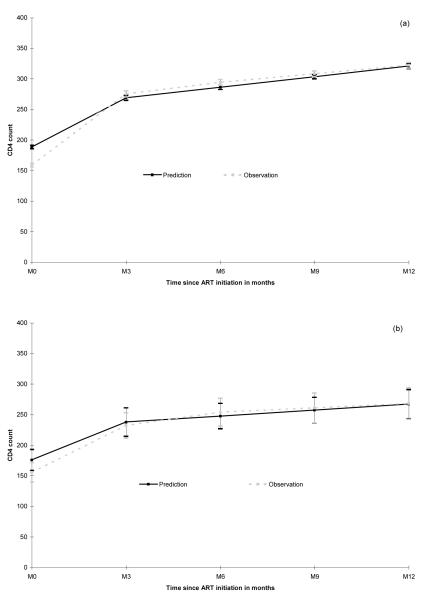

The observed baseline median CD4 counts were comparable in the three groups: 155 cells/μL in HIV-1, 148 in HIV-2 and 152 in dually positive patients (p=0.52, Table 1). The estimated baseline values according to the model were also not significantly different by type of infection (p=0.23). The good agreement between observed and predicted CD4 counts over time is illustrated in Figure 2. The slight overestimation of predicted baseline values was mostly related to missing observations at baseline.

Figure 2.

Predicted (from piecewise linear mixed model) and observed mean values of CD4 absolute count (95% Confidence Interval) for HIV-1 (a), HIV-2 (b) and dually positive patients (c). IeDEA West Africa Collaboration.

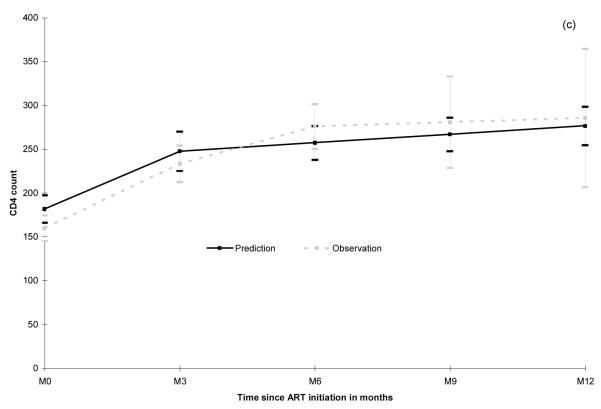

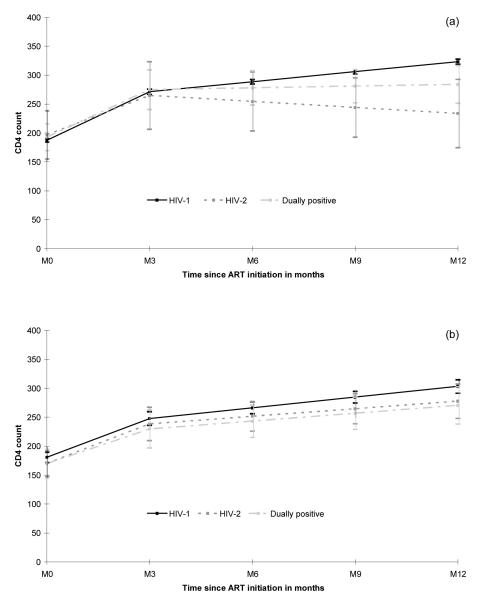

In patients treated with a NNRTI-containing regimen, the CD4 response was weaker in HIV-2 and dually positive patients compared to HIV-1 infected patients (Table 2, Figure 3). Although identical in the first three months on treatment (p=0.62), the CD4 response was gradually blunted beyond this time point (p=0.01) for HIV-2 infected patients (−41 cells/μL/year, CI= −x123; 40) and dually positive patients (+12 cells/μL/year, CI= −34; 58) compared to HIV-1 infected patients (+69 cells/μL/year, CI= 63; 75). This led to a significantly lower CD4 count 12 months after ART initiation in HIV-2 (268 cells/μL, CI= 175; 293) and dually positive patients (277 cells/μL, CI= 252; 317) compared to HIV-1 patients (321 cells/μL, CI= 319; 328) (p<.001). Of note, the CD4 response beyond the first three months on treatment was significantly better in dually positive patients compared to those infected by HIV-2 only (p=0.03). These results were highly consistent when adjusted for potential confounding factors (gender, age, clinical stage and previous exposure to antiretrovirals). Thus, the estimated CD4 slopes after three months for female patients older than 40 years, starting ART at CDC C stage (or WHO stage 3/4) and having never been exposed to antiretrovirals were +72, −30 and +14 cells/μL/year in HIV-1, HIV-2 and dually positive patients, respectively (p=0.03).

Table 2.

Estimation of the mean change (95% Confidence Interval) in cells/μL/month of the absolute CD4 count after ART initiation according to the type of antiretroviral regimen. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration.

| Antiretroviral combination |

HIV-1 | HIV-2 | Dually positive | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NNRTI-containing

regimen |

Slope during first 3 months |

+28 (27; 29) |

+23 (9;36) |

+27 (20; 35) |

0.62 |

| Slope after first 3 months |

+6 (5; 6) |

−3 (−10; 3) |

+1 (−3; 5) |

0.01 | |

|

PI-containing

regimen |

Slope during first 3 months |

+22 (20; 25) |

+23 (16; 29) |

+20 (13; 27) |

0.73 |

| Slope after first 3 months |

+6 (5; 8) |

+4 (1; 8) |

+5 (1; 8) |

0.37 | |

| Other regimen | Slope during first 3 months |

+16 (12; 21) |

+11 (−3; 25) |

+11 (−8; 30) |

0.49 |

| Slope after first 3 months |

+5 (3; 7) |

+4 (−4; 11) |

+4 (−6; 14) |

0.72 |

NRTI: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, NNRTI: Non Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor, PI: Protease Inhibitor

Wald test for at least one slope differing from the two others

Figure 3.

Estimated mean CD4 response (95% Confidence Interval) during the first year of treatment by HIV type in patients treated with NNRTI (a) and treated with PI (b).

In patients treated by a PI-containing regimen, the CD4 response did not differ significantly for the three HIV groups before (p=0.73) and after three months (p=0.37) (Table 2, Figure 3). The estimated CD4 counts at 12 months was thus similar in HIV-2 (278 cells/μL, CI= 248; 307, p=0.22) and dually positive (271 cells/μL, CI= 238; 303, p=0.25) patients compared to HIV-1 infected patients (303 cells/μL, CI= 292; 315). There were no significant differences of HIV type effect on CD4 response after three months between boosted and unboosted PI-based regimens (all p-values > 0.35).

In patients treated by another regimen neither containing a NNRTI nor a PI, the CD4 response was similar whatever the type of infection (p=0.49 and p=0.72, before and after three months). The results were similar even after adjustment for the potential confounding factors: age, gender, clinical stage at ART initiation and previous exposure to antiretrovirals (data not shown).

In all analyses, the CD4 responses varied substantially between individuals of the same group of treatment (variance of the individual slopes significantly different from 0, all p values < 0.01). This variation was less pronounced in the group of patients treated with an NNRTI-containing regimen, irrespective of the HIV type. In all groups of treatment, the results were consistent after adjusting for centres (data not shown).

Discussion

In this international collaboration of cohorts of HIV-infected adults including the largest sample of HIV-2 and dually positive patients treated by ARV ever reported, we found that 1) as expected the CD4 response was poor if the patient harboured HIV-2 and was treated with a NNRTI-containing regimen although it was better in dually positive compared to HIV-2 only infected patients 2) the efficacy of PI-containing regimens was comparable in HIV-1, HIV-2 and dually positive patients, in line for HIV-1 with other published reported [19, 26, 32, 38, 39].

There are several explanations for the use of NNRTI-based regimens in these HIV-2 and dually positive patients. First, the information on the HIV type was not always available at the time of treatment initiation. Occasionally, this information only became available after ART initiation and in the context of clinical progression. Second, in some participating clinical centres, NNRTI-containing regimens were the only treatment options available at a given time. This feature is mostly related to the challenging issue of the choice of second-line therapies in resource-limited settings [40]. Thirdly, an efavirenz-regimen may have been prescribed in order to avoid PI-rifampin interactions during TB-HIV co-treatment (although not recommended in HIV-2 infection). Finally, it is possible that some physicians did not know that NNRTIs are ineffective in HIV-2 infection. The individual justification of this therapeutic choice was not available in this dataset of routinely collected data. Overall, this underlines the need of country-specific medical education in the context of rapid scaling-up as recently advocated [32, 41]. If HIV type is not available, although recommended by the WHO-guidelines [42], it would be more appropriate to treat with a PI-based regimen or a triple therapy of NRTIs if the CD4 count is above 200 cells/μL in HIV-2 endemic countries [42].

Although PI-based regimens did better than those based on NNRTIs, all PIs did not present the same potency [21]. This underlines the need in studying further the efficacy of specific drugs in the special context of HIV-2 infection. In fact, observational studies like the present one cannot rule out a potential channelling bias. Furthermore, emergence of resistance mutations endorsed the need of increasing antiretroviral treatment potency in HIV-2 patients for the first and second line therapy [23]. We thus believe like others [43, 44] that there is a need to conduct new randomized clinical trials to optimise the care of HIV-2 infected patients.

A drawback of this study may be the absence of evaluation of virological response. Such data were not available as these tests are not routinely available. Nevertheless, the immunological response is one of the requested goals of any antiretroviral therapy and the one currently recommended by WHO in the public health approach of ARV [42]. We do not think that the selection for enrolment (based on availability of CD4 and HIV types) or during follow-up (due to withdrawal) could impact our conclusion because i) there was no strong differences between included and excluded patients according to HIV type, and ii) results were robust according to sensitivity analyses. Another issue is the lack of perfect discrimination between dually positive and HIV-2 infected patients [34]. Hence, the group of dually positive patients could have included a mixture of patients infected by HIV-2 only or both HIV-1 and HIV-2. However, the data from the present observational study come from routine practice and therefore endorse the need for confirmation algorithms of the dual infection by HIV-1 and 2 as well as the cautious use of NNRTI-containing regimens in such circumstances.

In conclusion, the scaling-up of ART in West Africa must fully incorporate the issue of HIV-2 infected patients, in term of medical training but also for the choice of appropriate medications and diagnostic protocols at clinic and programmatic level. Finally, randomized clinical trials evaluating the new generation of antiretroviral drugs in HIV-2 infected patients are warranted to better defined public health guidelines [3, 43, 44].

Acknowledgments

Roles of authors: J.D., R.T., D.K.E and F.D. designed the analysis and wrote the paper. J.D., and R.T. conducted the statistical analysis, S.E and K.P. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. S.E, M.M., M.D.Z, P.S.S, K.P., E.B. contributed to the design, data and original idea.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, grant 5U01AI069919-03), together with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

We would like to thank Xavier Anglaret for his valuable comments on a previous version of the article.

Footnotes

Preliminary results were presented at the 16th conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic infections, February 8-11, 2009, abstract #600.

Composition of the IeDEA-West Africa Collaboration Primary investigator: Pr François Dabis* (INSERM U897, ISPED, Bordeaux, France) Co-investigators: Clarisse Amani-Bosse, Franck Olivier Ba-Gomis, Emmanuel Bissagnene*, Man Charurat*, Eric Delaporte, Joseph Drabo*, Serge-Paul Eholie*, Serge-Olivier Koulé, Moussa Maiga*, Eugène Messou, Albert Minga, Kevin Peterson, Papa Salif Sow, Hamar Traoré, Marcel D Zannou*

Others members: Gérard Allou, Xavier Anglaret, Alain Azondékon, Eric Balestre, Jules Bashi, Ye-Diarra, Didier K Ekouévi*, Jean-François Eytard, Antoine Jaquet, Alain Kouakoussui, Valériane Leroy, Charlotte Lewden, Karen Malateste, Lorna Renner, Annie Sasco, Haby Signaté Sy*, Rodolphe Thiébaut, Marguerite Timité-Konan, Hapsatou Touré.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Geneva: Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector: progress report 2008. 2008

- 2.van der Loeff MF, Awasana AA, Sarge-Njie R, van der Sande M, Jaye A, Sabally S, et al. Sixteen years of HIV surveillance in a West African research clinic reveals divergent epidemic trends of HIV-1 and HIV-2. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:1322–1328. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eholie S, Anglaret X. Commentary: Decline of HIV-2 prevalence in West Africa: good news or bad news? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:1329–1330. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valadas E, Franca L, Sousa S, Antunes F. 20 Years of HIV-2 Infection in Portugal: Trends and Changes in Epidemiology. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:1166–1167. doi: 10.1086/597504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittle H, Morris J, Todd J, Corrah T, Sabally S, Bangali J, et al. HIV-2-infected patients survive longer than HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 1994;8:1617–1620. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199411000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry N, Ariyoshi K, Jaffar S, Sabally S, Corrah T, Tedder R, Whittle H. Low peripheral blood viral HIV-2 RNA in individuals with high CD4 percentage differentiates HIV-2 from HIV-1 infection. Journal of Human Virology. 1998;1:457–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacNeil A, Sarr AD, Sankale JL, Meloni ST, Mboup S, Kanki P. Direct evidence of lower viral replication rates in vivo in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) infection than in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Virology. 2007;81:5325–5330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02625-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele E Martinez, Awasana AA, Corrah T, Sabally S, van der Sande M, Jaye A, et al. Is HIV-2-induced AIDS different from HIV-1-associated AIDS? Data from a West African clinic. AIDS. 2007;21:317–324. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011d7ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Loeff MFS, Steele E Martinez, Corrah T, Awasana AA, van der Sande M, Njie R Sarge, et al. HIV-2-induced AIDS different from HIV-1-associated AIDS? AIDS. 2008;22:791–792. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f37824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schutten M, van der Ende ME, Osterhaus AD. Antiretroviral therapy in patients with dual infection with human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1758–1760. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witvrouw M, Pannecouque C, Switzer WM, Folks TM, De Clercq E, Heneine W. Susceptibility of HIV-2, SIV and SHIV to various anti-HIV-1 compounds: implications for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis. Antiviral Therapy. 2004;9:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matheron S, Damond F, Benard A, Taieb A, Campa P, Peytavin G, et al. CD4 cell recovery in treated HIV-2-infected adults is lower than expected: results from the French ANRS CO5HIV-2 cohort. AIDS. 2006;20:459–462. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000199829.57112.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jallow S, Kaye S, Alabi A, Aveika A, Sarge Njie R, Sabally S, et al. Virological and immunological response to Combivir and emergence of drug resistance mutations in a cohort of HIV-2 patients in The Gambia. AIDS. 2006;20:1455–1458. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233582.64467.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drylewicz J, Matheron S, Lazaro E, Damond F, Bonnet F, Simon F, et al. Comparison of viro-immunological marker changes between HIV-1 and HIV-2- infected patients in France. AIDS. 2008;22:457–468. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4ddfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RA, Anderson DJ, Pyrak CL, Preston BD, Gottlieb GS. Antiretroviral Drug Resistance in HIV-2: Three Amino Acid Changes Are Sufficient for Classwide Nucleoside Analogue Resistance. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;199:1323–1326. doi: 10.1086/597802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borget MY, Diallo K, Adje-Toure C, Chorba T, Nkengasong JN. Virologic and immunologic responses to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 and HIV-2 dually infected patients: case reports from Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2009;45:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benard A, Damond F, Campa P, Peytavin G, Descamps D, Lascoux-Combes C, et al. Good response to lopinavir/ritonavir-containing antiretroviral regimens in antiretroviral-naive HIV-2-infected patients. Aids. 2009;23:1171–1173. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832949f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarfo FS, Bibby DF, Schwab U, Appiah LT, Clark DA, Collini P, et al. Inadvertent non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based antiretroviral therapy in dual HIV-1/2 and HIV-2 seropositive West Africans: a retrospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jallow S, Alabi A, Sarge-Njie R, Peterson K, Whittle H, Corrah T, et al. Virological response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) and in patients dually infected with HIV-1 and HIV-2 in the Gambia and emergence of drug-resistant variants. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2200–2208. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01654-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren J, Bird LE, Chamberlain PP, Stewart-Jones GB, Stuart DI, Stammers DK. Structure of HIV-2 reverse transcriptase at 2.35-A resolution and the mechanism of resistance to non-nucleoside inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:14410–14415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222366699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brower ET, Bacha UM, Kawasaki Y, Freire E. Inhibition of HIV-2 protease by HIV-1 protease inhibitors in clinical use. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2008;71:298–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Descamps D, Damond F, Matheron S, Collin G, Campa P, Delarue S, et al. High frequency of selection of K65R and Q151M mutations in HIV-2 infected patients receiving nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors containing regimen. Journal of Medical Virology. 2004;74:197–201. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb GS, Badiane NMD, Hawes SE, Fortes L, Toure M, Ndour CT, et al. Emergence of Multiclass Drug-Resistance in HIV-2 in Antiretroviral-Treated Individuals in Senegal: Implications for HIV-2 Treatment in Resouce-Limited West Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:476–483. doi: 10.1086/596504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landman R, Damond F, Gerbe J, Brun Vezinet F, Yeni P, Matheron S. Immunovirological and therapeutic follow-up of HIV-1/HIV-2-dually seropositive patients. AIDS. 2009;23:426–428. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321305a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jallow S, Vincent T, Leligdowicz A, De Silva T, Van Tienen C, Alabi A, et al. Presence of a multidrug-resistance mutation in an HIV-2 variant infecting a treatment-naive individual in Caio, Guinea Bissau. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1790–1793. doi: 10.1086/599107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, Traore M, Dogbo N Dakoury, Duvignac J, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10000 adults in Cote d’Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008;22:873–882. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS - West Africa 2009.

- 28.Brinkhof MW, Boulle A, Weigel R, Messou E, Mathers C, Orrell C, et al. Mortality of HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: comparison with HIV-unrelated mortality. Plos Medicine. 2009;6:e1000066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hounton SH, Akonde A, Zannou DM, Bashi J, Meda N, Newlands D. Costing universal access of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Benin. AIDS Care. 2008;20:582–587. doi: 10.1080/09540120701868303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boileau C, Nguyen VK, Sylla M, Machouf N, Chamberland A, Traore HA, et al. Low prevalence of detectable HIV plasma viremia in patients treated with antiretroviral therapy in Burkina Faso and Mali. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;48:476–484. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817dc416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etard JF, Ndiaye I, Thierry-Mieg M, Gueye NF, Gueye PM, Laniece I, et al. Mortality and causes of death in adults receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegal: a 7-year cohort study. AIDS. 2006;20:1181–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226959.87471.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sow PS, Otieno LF, Bissagnene E, Kityo C, Bennink R, Clevenbergh P, et al. Implementation of an antiretroviral access program for HIV-1-infected individuals in resource-limited settings: clinical results from 4 African countries. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;44:262–267. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802bf109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiébaut R, Walker S. When it is better to estimate a slope with only one point. QJM Quaterly Journal of Medicine. 2008;101:821–824. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouet F, Ekouevi DK, Inwoley A, Chaix ML, Burgard M, Bequet L, et al. Field evaluation of a rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serial serologic testing algorithm for diagnosis and differentiation of HIV type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and dual HIV-1-HIV-2 infections in West African pregnant women. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:4147–4153. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4147-4153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pakker NG, Notermans DW, de Boer RJ, Roos MT, de Wolf F, Hill A, et al. Biphasic kinetics of peripheral blood T cells after triple combination therapy in HIV-1 infection: a composite of redistribution and proliferation. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gadda H Jacqmin, Sibillot S, Proust C, Molina JM, Thiébaut R. Robustness of the linear mixed model to misspecified error distribution. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2007;51:5142–5154. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiébaut R, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Babiker A, Commenges D. Joint modelling of bivariate longitudinal data with informative dropout and left-censoring, with application to the evolution of CD4+cell count and HIV RNA viral load in response to treatment of HIV infection. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:65–82. doi: 10.1002/sim.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nash D, Katyal M, Brinkhof MW, Keiser O, May M, Hughes R, et al. Long-term immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. AIDS. 2008;22:2291–2302. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283121ca9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pujades-Rodriguez M, O’Brien D, Humblet P, Calmy A. Second-line antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: the experience of Medecins Sans Frontieres. AIDS. 2008;22:1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fa75b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Souville M, Msellati P, Carrieri MP, Brou H, Tape G, Dakoury G, Vidal L. Physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward HIV care in the context of the UNAIDS/Ministry of Health Drug Access Initiative in Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2003;17(Suppl 3):S79–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization Geneva: Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents : recommendations for a public health approach. 2006 –2006 revision. [PubMed]

- 43.Gottlieb GS, Eholie SP, Nkengasong JN, Jallow S, Rowland-Jones S, Whittle HC, Sow PS. A call for randomized controlled trials of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-2 infection in West Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:2069–2072. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830edd44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matheron S. HIV-2 infection: a call for controlled trials. AIDS. 2008;22:2073–2074. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830edd44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]