Abstract

Vitamin D is not just for preventing rickets and osteomalacia. Recent findings in animal experiments, epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, indicate that adequate vitamin D levels are important for cancer prevention, controlling hormone levels, and regulating the immune response. Although 25 Hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) levels above 10ng/ml may prevent rickets and osteomalacia, these levels are not sufficient to provide these more recently discovered clinical benefits. Rather, levels of 25OHD above 30ng/ml are generally recommended. Determining optimal levels of 25OHD and the amount of vitamin D supplementation required to achieve those levels for the numerous actions of vitamin D will only be established with additional trials. In this review, these newer applications are summarized and therapeutic considerations provided.

The vitamin D receptor (VDR), the nuclear hormone receptor that mediates most if not all of the functions of its preferred ligand 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) or calcitriol, is found in most tissues of the body. Thus it has been suspected for some time that vitamin D exerts its actions not only on classic tissues regulating calcium homeostasis such as bone, gut and kidney, but also on other tissues. Indeed, many of these tissues also contain the enzyme, CYP27B1 [1], which converts the major circulating metabolite of vitamin D, 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD), to 1,25(OH)2D. This enzyme, originally thought to be found only in the kidney, is now known to contribute to local production of 1,25(OH)2D3 [1] and to tissue-specific responses to vitamin D. Furthermore, regulation of CYP27B1 in non-renal tissues generally differs from that in the kidney, and may be more dependent on the concentration of available 25OHD substrate [1]. This has led to the concept that maintenance of 25OHD levels in the blood above that required for the prevention of rickets and osteomalacia is required for vitamin D regulation of a large number of physiologic functions beyond that of its classic actions in bone mineral metabolism. This review first covers the basics of vitamin D production, metabolism and molecular mechanism of action and then examines the impact of vitamin D on a number of non-classical tissues, exploring how vitamin D deficiency contributes to various pathologic conditions in these tissues.

Vitamin D production

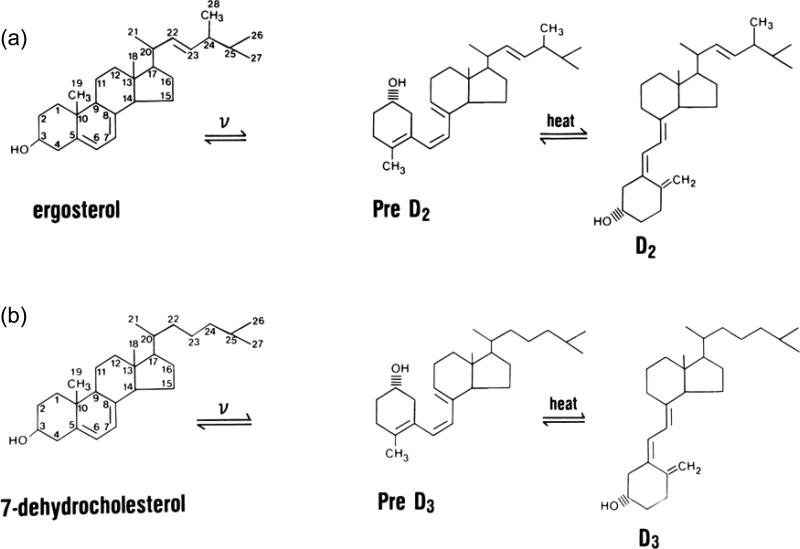

Two forms of vitamin D exist: vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) (Figure 1). The former is produced in the skin under the influence of ultraviolet B radiation (UVR), while the latter, also produced by UVR, is produced in a variety of plant materials and yeast. Differences exist in their binding to the major transport protein in blood, vitamin D binding protein (DBP), and in their metabolism because of the different structures of their side chains. In humans, 25OHD2 is cleared from the blood faster after a single dose of vitamin D2 than 25OHD3 after a comparable dose of vitamin D3 [2]. However, when given daily in equivalent amounts, vitamins D2 and D3 result in comparable levels of 25OHD [3]. This becomes important in terms of dosing, a subject that will be returned to in our discussion of treatment. At the tissue level, these differences appear to be minor in that the biologic activity of 1,25(OH)2D2 and 1,25(OH)2D3 are comparable at least with respect to binding VDR.

Figure 1. Vitamin D production and metabolism.

Vitamin D exists in two forms, vitamin D2 and vitamin D3. In each case vitamin D is produced from a precursor by ultraviolet B radiation (v). (a) Vitamin D2 is made in plants and yeast from ergosterol, whereas (b) vitamin D3 is made in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol. These forms of vitamin D differ in their side chains: vitamin D2 has a double bond between C22-23 and a methyl group at C24 that vitamin D3 lacks. However, vitamin D by itself is not biologically active but must first be converted to 25OHD (the major circulating form of vitamin D) and then to 1,25(OH)2D, the most biologically active metabolite. (c) The 25-hydroxylation occurs primarily in the liver, although other tissues have the requisite enzymatic activity. The major 25-hydroxylases in the liver include the mitochondrial enzyme CYP27A1 and the microsomal enzyme CYP2R1 (among others). 25OHD is then converted to its active form 1,25(OH)2D primarily in the kidney by the enzyme CYP27B1. As for the 25-hydroxylases, numerous tissues in addition to the kidney express CYP27B1. (i) In the kidney 1,25(OH)2D production is stimulated by PTH and low serum levels of calcium and phosphate, but inhibited by FGF23. Also in the kidney and elsewhere is the enzyme CYP24 which converts 25OHD to 24,25(OH)2D and 1,25(OH)2D to 1,24,25(OH)3D. Although these metabolites have been shown to have biologic activity, the 24-hydroxylation is also the first step in catabolizing vitamin D metabolites. (ii) The regulation of CYP24 by PTH, FGF23, calcium, and phosphate is essentially the reverse of that of CYP27B1, at least in the kidney, and 1,25(OH)2D is a potent inducer of its expression. Regulation of these enzymes in non-renal tissues differs from that in the kidney.

Vitamin D3 (D3) is produced in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) through a two step process in which the B ring is broken under UVR (eg. sunlight), forming pre-D3 that isomerizes to D3 in a thermo-sensitive but non enzymatic process (Figure 1). Both UVR intensity and skin pigmentation contribute to D3 formation [4]. Prolonged UVR exposure (eg. sufficient to produce a sunburn) will not result in toxicity because with prolonged exposure, non biologically active products of D3 are formed [5]. Melanin in the skin blocks UVR from reaching 7-DHC, thus limiting D3 production, as do clothing and sunscreen. The intensity of UVR from sunlight varies according to season and latitude, so the further one lives from the equator, the less time of the year one can rely on solar exposure to produce D3 [6]

Vitamin D Metabolism

To be biologically active, vitamin D must first be converted to 25OHD (Figure 1). A number of enzymes, both mitochondrial and microsomal, are capable of this function [7]. These enzymes are found in many tissues, and their activity is limited primarily by substrate, ie. vitamin D, availability [8] . As such, serum 25OHD is a reliable indicator of vitamin D status [9]. To be fully active, 25OHD must be further converted to 1,25(OH)2D via CYP27B1. Although the proximal renal tubule is the major source of 1,25(OH)2D production for the body, the enzyme is also found in a number of extrarenal sites such as immune cells, epithelia of skin, gut, prostate, breast, lung, bone and parathyroid glands [10], where it may provide 1,25(OH)2D for local use as an intracrine or paracrine factor. Regulation of CYP27B1 in the proximal renal tubule is controlled by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and FGF-23, which stimulate and inhibit, respectively, its expression [1]. Additionally 1,25(OH)2D3 negatively regulates its own levels by inducing CYP24 [11], another mitochondrial P450 enzyme that catabolizes both 1,25(OH)2D and 25OHD[12]. Control of 1,25(OH)2D3 production by non-renal tissues differs. For example, in macrophages, CYP27B1 is induced when these cells are activated by an invading organism [13]. A similar situation exists in keratinocytes [14, 15].

Mechanism of Action

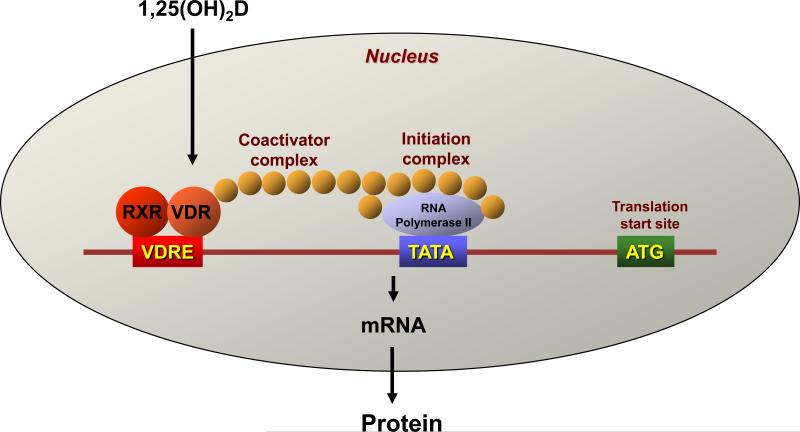

The mechanism of action of the active form of 1,25(OH)2D is similar to that of other steroid hormones and is mediated by binding to VDR (Figure 2). VDR is a member of the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors including receptors for steroid and thyroid hormones and retinoic acid. VDR functions as a heterodimer generally with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to regulate vitamin D target genes [16, 17]. These heterodimeric complexes interact with specific DNA sequences (vitamin D response elements; VDRE) [18, 19] that can be located within introns and/or at large distances from the transcription start site [16, 17, 20, 21]. The control of transcription requires the additional recruitment of co-regulators [22] that can be inhibitory (co-suppressors) or stimulatory (co-activators). Different tissues have varying levels of these co-regulators, providing some degree of tissue specificity for vitamin D action. Furthermore, different genes are selective for the co-regulator that in combination with VDR regulates their transcription [23]. Thus an appreciation of the ability of individual tissues to produce their own 1,25(OH)2D3 in a tissue specific fashion and to respond to 1,25(OH)2D3, again in a tissue specific fashion, provides the basis for the concept that vitamin D regulates many functions in many tissues, and does so selectively.

Figure 2. The mechanism of action of 1,25(OH)2D.

1,25(OH)2D is a sterol hormone, and shares the property of other steroid hormones, thyroid hormone, and retinoic acid as a ligand for a transcription factor, which in the case of 1,25(OH)2D is the vitamin D receptor (VDR). VDR is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family. When 1,25(OH)2D binds to VDR it is transported into the nucleus where it partners with another nuclear hormone receptor, most often the retinoid X receptor (RXR). These heterodimers bind to regions of the genes they regulate at specified sequences called vitamin D response elements (VDRE). Binding to the VDREs is accompanied by the formation of large complexes that can facilitate the expression of the targeted gene (coactivators) or inhibit its expression (cosuppressors). There are a number of different types of coactivator complexes that function either to expose the gene for transcription by acetylating the histones that otherwise conceal the DNA, or by bridging the gap between the VDRE and the initiation complex, stimulating transcription by activating the RNA polymerase as shown in this figure. Corepressors block this process in part by deacetylating the histones, although other modifications of these histones such as methylation have also been reported.

Maintaining skeletal health

Studies have examined whether vitamin D supplementation prevents fractures, with conflicting results. Bischoff-Ferrari et al. [24] recently published a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT) examining the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on fracture prevention with or without supplementary calcium in subjects over 65 years old. These studies included non-vertebral fractures (12 RCTs, 42,279 subjects) or hip fractures (8 RCT, 40,886 subjects). Studies using 400 IU vitamin D or less did not show benefit [24], whereas studies using more than 400 IU vitamin D showed a significant reduction (approximately 20%) in fractures [24]. Part of this reduction might come from increased bone mineral density in those receiving vitamin D supplements, but part of the benefit might also come from improved neuromuscular function and a decreased risk of falling [25].

Regulation of hormone secretion

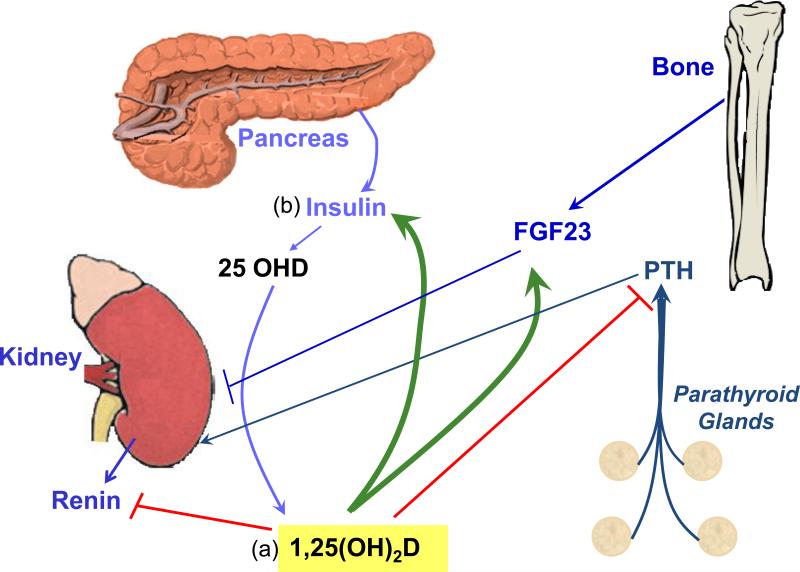

1,25(OH)2D regulates the production and secretion of a number of hormones (Figure 3), which in some cases feedback on renal production of 1,25(OH)2D3. Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to a variety of diseases resulting from either over or under secretion of such hormones, providing a physiologic basis for the importance of this regulation. The following are examples.

Figure 3. Hormonal regulation by and of 1,25(OH)2D.

(a) 1,25(OH)2D inhibits (red lines) the production of PTH and renin while stimulating (green arrows) that of FGF23 and insulin. PTH and FGF23 in turn are major regulators of 1,25OH)2D production by the kidney, PTH stimulating (arrow) while FGF23 inhibits (line). (b) Insulin may also stimulate 1,25(OH)2D production, perhaps through insulin like growth factor (IGF)-I receptor, although this possibility has received limited evaluation.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH)

1,25(OH)2D inhibits the synthesis and secretion of PTH [26] and prevents proliferation of the parathyroid gland [26, 27]. 1,25(OH)2D also upregulates the calcium sensing receptor (CaR)[28], which sensitizes the parathyroid gland to calcium inhibition, providing an additional means of regulating PTH production and secretion. This is an appropriate feedback mechanism in that PTH is a major stimulator of renal 1,25(OH)2D production. Hyperparathyroidism is a feature of vitamin D deficiency and contributes to bone loss; thus, PTH levels are a useful marker to follow when vitamin D supplementation is initiated to correct vitamin D deficiency. Of interest is that PTH levels in subjects with normal renal function correlate better with circulating 25OHD levels than with circulating 1,25(OH)2D levels, suggesting that the parathyroid gland makes its own 1,25(OH)2D from circulating 25OHD [29]. These actions of 1,25(OH)2D are exploited clinically through the use of 1,25(OH)2D and analogs to control secondary hyperparathyroidism in renal failure [27].

Insulin

1,25(OH)2D stimulates insulin secretion, presumably by regulating calcium flux, although the mechanism is not well defined [30, 31]. Pittas et al. [32] recently published a meta-analysis of studies demonstrating a link between vitamin D deficiency and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). In particular, in non-blacks, the relative risk (RR) of type 2 DM was 0.36 in those with the highest 25OHD levels compared to those with the lowest levels [32]. A similar inverse relationship was observed for the metabolic syndrome. In a recent Finnish trial with a 22 yr follow up of 7503 subjects free of DM at the beginning of the trial, subjects with the highest 25OHD levels at the start of the trial had a relative risk (RR) of 0.6 for developing DM compared to those with the lowest 25OHD levels [33]. Long term randomized controlled trials with vitamin D supplementation are needed to confirm these mostly observational cross-sectional and case control studies.

Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23)

FGF23 is produced primarily by bone, in particular by osteoblasts and osteocytes. 1,25(OH)2D stimulates FGF23 production [34]. Inasmuch as FGF23 inhibits 1,25(OH)2D production by the kidney, this feedback loop, like that for PTH secretion, maintains a balance in these hormone levels. FGF23 is also a major regulator of phosphate handling by the kidney, and phosphate, like 1,25(OH)2D, provides feedback regulation of FGF23 production [35]. A number of diseases are caused by overproduction or underproduction of FGF23 leading to abnormalities in vitamin D metabolism and phosphate handling. Mutations in the Phosphate regulating gene with Homologies to Endopeptidases on the X chromosome (PHEX) are the cause of X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets, marked by elevated FGF23 levels and low phosphate and 1,25(OH)2D levels [36]. Mutations in FGF23 itself (which prevent its proteolysis) are the cause of Autosomal Dominant Hypophosphatemic Rickets (ADHR) with a similar phenotype [37]. Conditions such as McCune-Albright disease and tumor induced osteomalacia in which FGF23 is overexpressed in the involved tissue lead to hypophosphatemia and inappropriately low 1,25(OH)2D levels accompanied by osteomalacia [38]. In contrast, mutations in UDP-N-acetyl-α–D galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GALNT3) [39], which glycosylates FGF23, or in FGF23 which block this glycosylation [40] result in inhibited FGF23 secretion leading to hyperphosphatemia, increased 1,25(OH)2D, and tumoral calcinosis [35]. The role of FGF23 in vitamin D deficiency per se has not yet been carefully examined, although in chronic kidney disease, elevated FGF23 levels may contribute to the osteomalacia frequently observed.

Renin

The juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney produce renin, a protease that converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I, which is subsequently converted to angiotensin II, a major regulator of aldosterone production and vascular tone. Mice lacking the ability to produce or respond to 1,25(OH)2D (CYP27B1 null, VDR null, respectively) have increased renin production leading to increased angiotensin II, hypertension, and cardiac hypertrophy [41, 42]. The negative regulation of renin/angiotensin by 1,25(OH)2D may explain the inverse correlation between 25OHD levels and both hypertension and heart disease. In a 10 year study of 18,225 men in the Health Professionals Follow up study, subjects in the lowest quartile of 25OHD levels at the start of the study (<15ng/ml) had a 2-2.4 fold increased risk of myocardial infarction relative to those in the highest quartile (>30ng/ml) [43]. Similarly, a study combining results from the Health Professionals Follow up study and those from the Nurses’ Health Study found that those in the lowest quartile of 25OHD levels were more likely to develop hypertension (RR 6.13 for men, 2.67 for women) than those in the highest quartile [44]. The renin/angiotensin system is also thought to play an important role in the development of diabetic nephropathy independent of its effects on blood pressure. Zhang et al. [45], using a mouse model of type 1 diabetes mellitus (streptozotocin treatment), demonstrated that the combination of a 1,25(OH)2D analog (paricalcitol) and an angiotensin receptor inhibitor (losartan) blocked the development of nephropathy, with the combination being more effective than either agent alone.

Regulation of Immune Function

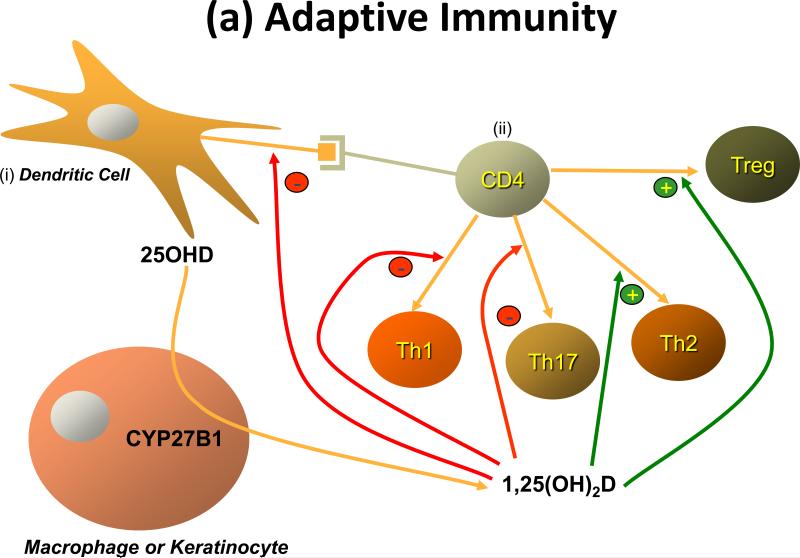

The potential role for vitamin D and its active metabolite 1,25(OH)2D to modulate the immune response rests on the observations that VDR are found in activated dendritic cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes [46, 47], that these cells produce 1,25(OH)2D (i.e. express CYP27B1) [46], and that 1,25(OH)2D regulates their proliferation and function [48]. Two forms of immunity exist - adaptive and innate - and each are regulated by 1,25(OH)2D (Figure 4).

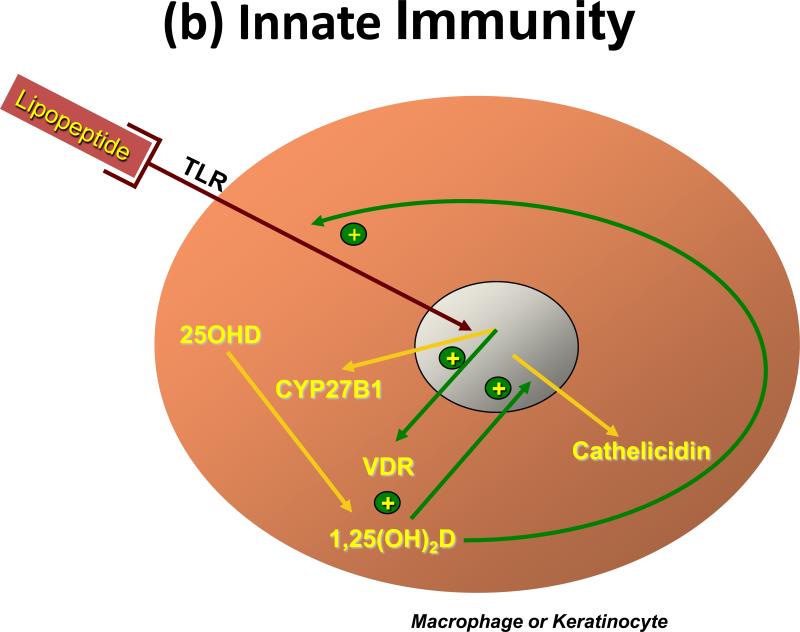

Figure 4. Regulation of immunity by 1,25(OH)2D.

(a) Adaptive immunity. Antigen presenting cells, primarily dendritic cells and macrophages but in some cases other cells like keratinocytes, when activated induce the proliferation and differentiation of T cells (CD4 and CD8) along different pathways depending on a variety of conditions including cell context and type of antigen activating the system. (i)The dendritic cell is shown stimulating (ii) the CD4 cell to differentiate into one of 4 different types of T helper (Th) cell. 1,25(OH)2D influences this process by inhibiting the development of Th1 and Th17 cells, while promoting that of Th2 and Treg cells. (b) Innate immunity. The innate immune response is triggered by a wide variety of environmental stimuli including various infectious organisms. These act through toll like receptors (TLR). Many cells including professional immune cells and a number of epithelial cells express TLRs and are capable of mounting the innate immune response. Several of these TLRs, when activated, induce VDR and CYP27B1, which given adequate substrate (25OHD), results in 1,25(OH)2D production within the cell. 1,25(OH)2D in turn binds to the VDR to induce antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin capable of killing the invading organism. The innate immune response is also critical for activating the adaptive immune response, but the role of 1,25(OH)2D in this process has received limited study.

Adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune response involves the ability of T and B lymphocytes to produce cytokines and immunoglobulins, respectively, to specifically combat the source of the antigen presented to them by cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Vitamin D exerts an inhibitory action on the adaptive immune system. In particular, 1,25(OH)2D suppresses proliferation and immunoglobulin production and retards the differentiation of B-cell precursors into plasma cells[47]. In addition 1,25(OH)2D inhibits T cell proliferation [49], in particular the Th1 cells capable of producing IFN-γ and IL-2 and activating macrophages [50] and Th17 cells capable of producing IL17 and IL22 [51, 52] (Figure 4). In contrast IL-4, IL-5, and IL10 production increase [53], shifting the balance to a Th2 cell phenotype. CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) are also increased by 1,25(OH)2D3 [54] leading to increased IL-10 production. The IL-10 so produced is one means by which Treg block Th1 and Th17 development. At least in part these actions on T cell proliferation and differentiation stem from actions of 1,25(OH)2D on dendritic cells to reduce their maturation and antigen presenting capability [55]. The ability of 1,25(OH)2D to suppress the adaptive immune system is beneficial for conditions in which the immune system is directed at self, ie. autoimmunity [56] and following transplants [57].

An increased incidence of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 DM and multiple sclerosis has been associated with vitamin D deficiency. The 1,25(OH)2D analog calcipotriol is approved for treatment of the Th1/Th17 mediated skin disease psoriasis [58], and clinical trials are under way for other autoimmune disorders. However, Th2 mediated diseases such as atopic dermatitis and asthma may be worsened by 1,25(OH)2D and its analogs [59], and infections requiring an adaptive immune response for protection may likewise be impaired by 1,25(OH)2D [60]. However, for asthma, vitamin D deficiency has been linked to increased incidence of this disease, not a decrease [61], demonstrating the need for randomized controlled trials with vitamin D supplementation in this area.

Innate immunity

The innate immune response is the critical first line of defense against invading pathogens. The response involves the activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) in polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), monocytes and macrophages as well as in a number of epithelial cells including those of the epidermis, gingiva, intestine, vagina, bladder and lungs [62]. TLRs are transmembrane pathogen-recognition receptors that interact with specific membrane patterns (PAMP) shed by infectious agents that trigger the innate immune response in the host [63]. Activation of TLRs leads to the induction of antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species, which kill the organism. Among those antimicrobial peptides is cathelicidin. The expression of this antimicrobial peptide is induced by 1,25(OH)2D in both myeloid and epithelial cells [64, 65] that also express CYP27B1 and so are capable of producing 1,25(OH)2D needed for this induction (Figure 4). Stimulation of TLR2 by an antimicrobial peptide in macrophages [13] or stimulation of TLR2 in keratinocytes by wounding the epidermis [14] results in increased CYP27B1 expression, which in the presence of adequate substrate (25OHD), stimulates cathelicidin expression. Lack of substrate (25OHD), VDR, or CYP27B1 blunts the ability of these cells to respond to a challenge with respect to cathelicidin production [13, 14, 65]. It has long been appreciated that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased susceptibility to tuberculosis [66], and sunlight was the prescribed therapy before antituberculosis drugs became available. Both macrophages and bronchial epithelia produce 1,25(OH)2D and cathelicidin, enabling them to resist infection by M. tuberculosis [64, 65]. Similarly, the skin is resistant to infections by organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus as a result of 1,25(OH)2D induced cathelicidin in keratinocytes when activated by this organism [67].

Regulation of proliferation and differentiation

The proliferation and differentiation of many cell types is controlled, at least to some degree, by vitamin D and its metabolites. As such, the role of vitamin D in the prevention and/or treatment of conditions where such regulation goes awry has received considerable attention. Much interest has focused on cancer prevention and treatment. 1,25(OH)2D has been evaluated for its potential anticancer activity in animal and cell studies. The list of malignant cells that express VDR is now quite extensive. 1,25(OH)2D stimulates the expression of cell cycle inhibitors p21 and p27 [68] and the expression of the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin [69], while inhibiting transcriptional activity of β-catenin [69-71]. These actions would be expected to block proliferation of these cells. In keratinocytes, 1,25(OH)2D promotes the repair of DNA damage induced by ultraviolet radiation (UVR) [72] and increases p53 [73]. Epidemiologic evidence supporting the importance of adequate vitamin D nutrition (including sunlight exposure) for the prevention of a number of cancers is extensive as recently reviewed [74]. In one study, 25OHD levels >33ng/ml showed a RR of colorectal cancer development that was half that of the group with 25OHD levels <12ng/ml [75]. However, a recent report from the Women's Health Initiative failed to find a reduction in colon cancer in women receiving 400 IU vitamin D plus 1000mg calcium [76], although this study has been criticized for using too low a dose of vitamin D, poor compliance, and failure to control for vitamin D and calcium supplementation in the placebo group. A report from the Nurses’ Health Study indicated that women in the highest quintile of 25OHD levels at the start of the study had a reduced risk of breast cancer of approximately 27% [77]. The relationship of 25OHD levels and prostate cancer has been less clear. One recent study indicated no significant trend between 25OHD levels and prostate cancer development. Instead an alarming trend associating higher 25OHD levels with more aggressive prostate cancer was found [78].

Data from prospective trials with vitamin D and its metabolites are limited. A prospective 4 yr trial with 1100 IU vitamin D and 1400-1500 mg calcium showed a 77% reduction in cancers (multiple types) after excluding the initial year of study [79]. In this study, vitamin D supplementation raised the 25OHD levels from a mean of 28.8ng/ml to 38.4ng/ml with no changes in the placebo or calcium-only groups. However, this was a relatively small study in which cancer prevention was not the primary outcome variable. Trials with 1,25(OH)2D and its analogs for the treatment of cancer have been disappointing and limited by hypercalciuria. One such study involving 250 patients with prostate cancer using 45μg 1,25(OH)2D weekly in combination with docetaxel demonstrated a non significant decline in PSA, although survival was significantly improved (HR 0.67) [80]. A larger study with a similar therapeutic regimen is in progress, but the results have not yet been reported. Most likely until an analog of 1,25(OH)2D is developed which is both efficacious and truly non hypercalcemic, treatment of cancer with vitamin D metabolites will remain problematic.

Therapeutic considerations

Defining vitamin D sufficiency

Serum 25OHD levels, collectively constituted by 25OHD2 from nutritional sources and 25OHD3 from both cutaneous sources and nutritional sources, provide a useful surrogate for assessing vitamin D status. 1,25(OH)2D levels, unlike 25OHD levels, are well maintained until the extremes of vitamin D deficiency because of secondary hyperparathyroidism, and so do not provide a useful index for assessing vitamin D deficiency at least at the initial stages. Historically, vitamin D sufficiency was defined as the level of 25OHD sufficient to prevent rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. Levels of 25OHD below 5ng/ml (or 12nM) are associated with a high prevalence of rickets or osteomalacia [81], and current “normal” levels of 25OHD are often stated to include levels as low as 15ng/ml. There is a growing consensus that these lower limits of ‘normal’ are too low [9]. Although there is currently no consensus for optimal levels, most experts define vitamin D deficiency as levels of 25OHD below 20ng/ml and optimal levels above 30ng/ml [9]. With this definition of vitamin D deficiency, a very large proportion of the population in both the developed and developing world are vitamin D deficient [9].

Vitamin D treatment strategies

Adequate sunlight exposure is the most cost effective means of obtaining vitamin D. Whole body exposure to enough UVB radiation or sunlight to provide a mild reddening of the skin (minimal erythema unit) has been calculated to provide the equivalent of 10,000 IU vitamin D3 [82]. Duration of exposure depends on skin pigmentation and sunlight intensity. A 0.5 minimal erythema dose of sunlight (ie. half the dose required to produce a slight reddening of the skin) or UVB radiation to the arms and legs, which can be achieved in 5-10 min on a bright summer day in a fair skinned individual in Boston, has been calculated to be the equivalent of 3000 IU vitamin D3 [9]. However, concerns regarding the association between sunlight and skin cancer and/or photoaging have limited this approach, perhaps to the extreme, although it remains a viable option for those unable or unwilling to benefit from oral supplementation. Current recommendations for daily vitamin D supplementation (200 IU for children and young adults, 400 IU for adults 51-70, and 600 IU for adults older than 71) are too low, and do not maintain 25OHD at the desired level for many individuals. Recently the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended increasing the dose to 400 IU for children. A number of studies demonstrated that for every 100 IU vitamin D3 supplementation administered on a daily basis for four or more months, 25OHD levels rise by 0.5-1ng/ml [82, 83]. Thus to increase a patient's 25OHD level from 20ng/ml to 30ng/ml, the supplementation would need to be 1000-2000 IU per day. As previously discussed, 700-800 IU appears to be the lower limit of vitamin D supplementation required to prevent fractures and falls. Unfortified food contains little vitamin D with the exception of wild salmon and other fish products such as cod liver oil. Milk and other fortified beverages typically contain 100 IU/8oz serving. The 25OHD level after a single 50,000 IU dose of D2 returns to baseline by 2 wks, whereas a comparable dose of D3 results in elevated 25OHD levels for over 1 month [2]. However, as mentioned previously, when given on a daily basis, 25OHD levels are equally well maintained with either form of vitamin D [3]. Therefore, if vitamin D2 is used, it needs to be given at least weekly. Toxicity due to vitamin D supplementation has not been observed at doses less than 10,000 IU per day [84], although such doses are seldom required except in situations in which vitamin D is poorly absorbed (malabsorption syndromes). Toxicity manifests as hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, leading to renal failure as a result of nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis and neurologic symptoms including coma.

Summary and Conclusions

Vitamin D regulates numerous physiologic processes in addition to maintaining calcium homeostasis through its actions on bone, intestine, and kidney. These non-classical actions include regulating the production and secretion of a number of hormones, controlling cellular proliferation and differentiation, and modulating both the adaptive and innate immune response. These pleiotropic actions reflect the ubiquitous distribution of VDR and the enzyme, CYP27B1, that produces the preferred ligand for VDR, 1,25(OH)2D. Although the kidney is the principle source for circulating 1,25(OH)2D, other tissues can make their own 1,25(OH)2D for intracrine or paracrine purposes. The kidney maintains adequate levels of 1,25(OH)2D production even in the face of modest degrees of vitamin D deficiency as a result of secondary hyperparathyroidism, but that is not the case for other tissues which lack responsiveness to PTH. Thus, maintaining adequate circulating levels of 25OHD is necessary to optimize these non-classical actions of vitamin D. At this point the optimal level of 25OHD is not clear for any of these non-classical actions, and more prospective trials need to be performed (Box 1). Nevertheless, based on current data, a level above 30ng/ml is considered sufficient. This level can be achieved with judicious exposure to sunlight at suberythemal doses and/or oral supplementation with vitamin D at doses generally above those officially recommended. Because of individual variation in the extent of epidermal production of vitamin D and in dietary intake, it is difficult to make a ‘one size fits all’ recommendation as to levels of oral supplementation (Box 2). The goal is to achieve serum levels of 25OHD that are optimal for the numerous functions vitamin D plays in the body.

Box 1.Outstanding questions.

What is the optimal level of vitamin D supplementation and/ or level (25OHD) in the blood to achieve maximal benefit for the numerous actions of vitamin D?

Do each of the various actions of vitamin D have an optimal level?

Should everyone have their 25OHD levels measured? If so, at what age and how often, if not under what circumstances should 25OHD levels be determined?

Is vitamin D supplementation given orally equally effective to vitamin D produced endogenously in the skin?

Would vitamin D supplementation started at age 60 be equally protective for fracture prevention or cancer prevention (after the first year of treatment) as vitamin D supplementation begun much earlier?

Box 2. Therapeutic Considerations.

The goal of treatment is to achieve a level of 25OHD in the blood optimal for the numerous physiologic functions regulated by vitamin D and its active metabolites.

With the exception of individuals with renal failure, it is not necessary and may even be detrimental to use vitamin D analogs instead of vitamin D itself to treat vitamin D deficiency.

Although the optimal level is not well established for many of the more recently described functions of vitamin D, current evidence suggests that 30ng/ml 25OHD is a reasonable target.

Since the diet is not rich in vitamin D, most of the vitamin D must come from its production in the skin or from dietary supplements.

Moderate exposure of non protected skin to sunlight (UVB) at doses that do not cause sunburn is a cost effective and safe way of achieving adequate vitamin D levels—the time of exposure to achieve adequate levels depends on the intensity of the sunlight and the pigmentation in the skin.

Dietary vitamin D supplementation is effective in situations where sun exposure is inadequate. Although doses as high as 10,000 IU/day have proven safe, daily doses in the 1000-2000 IU range generally suffice.

Single doses of vitamin D2 result in lower levels of circulating 25OHD after 1-2 wks than that of vitamin D3, but if given daily vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 result in comparable serum 25OHD levels. There are no compelling data to indicate that the active metabolites of vitamins D2 and D3 differ significantly in their biologic activity.

Glossary

- CYP27B1

25OHD 1alpha hydroxylase (the enzyme that produces 1,25(OH)2D)

- CYP24

25OHD 24 hydroxylase (the enzyme that degrades 1,25(OH)2D and 25OHD)

- 1,25(OH)2D

1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D, the preferred ligand for the vitamin D receptor

- 7-DHC

7 dehydrocholesterol, the precursor in skin for vitamin D production

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- DBP

vitamin D binding protein, the major carrier of vitamin D metabolites in the circulation

- FGF23

fibroblast growth factor 23, a major regulator of phosphate reabsorption and 1,25(OH)2D production in the kidney

- IFN

interferon, a family of cytokines

- IL

interleukin, a family of cytokines

- 25OHD

25 hydroxyvitamin D, the major circulating metabolite of vitamin D

- PSA

prostate specific antigen, a protease, serves as a marker for prostate cancer

- PTH

parathyroid hormone, a major regulator of calcium and phosphate homeostasis including 1,25(OH)2D production

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RR

relative risk

- RXR

retinoid X receptor, the most common partner for VDR in its transcriptional activity

- Th

helper T cell, a class of lymphocytes

- TLR

toll like receptor, pattern recognition receptor triggering the innate immune response

- UVR

ultraviolet radiation

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bikle D. Extra renal synthesis of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D and its Health Implications. Clin Rev in Bone and Min Metab. 2009;7:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armas LA, et al. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5387–5391. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF, et al. Vitamin D2 is as effective as vitamin D3 in maintaining circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:677–681. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick MF, et al. Photosynthesis of previtamin D3 in human skin and the physiologic consequences. Science. 1980;210:203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.6251551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holick MF, et al. Regulation of cutaneous previtamin D3 photosynthesis in man: skin pigment is not an essential regulator. Science. 1981;211:590–593. doi: 10.1126/science.6256855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb AR, et al. Sunlight regulates the cutaneous production of vitamin D3 by causing its photodegradation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:882–887. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-5-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prosser DE, Jones G. Enzymes involved in the activation and inactivation of vitamin D. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2004;29:664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gascon-Barré M. The Vitamin D 25-Hydroxylase. Elsevier. 2005;1:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewison M, et al. Extra-renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in human health and disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura A, et al. Regulation of messenger ribonucleic acid expression of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase in rat osteoblasts. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1794–1799. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.4.8137744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zierold C, et al. Two vitamin D response elements function in the rat 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 24-hydroxylase promoter. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1675–1678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu PT, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauber J, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:803–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI30142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikle DD, et al. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production in human keratinocytes by interferon-gamma. Endocrinology. 1989;124:655–660. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-2-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakos S, et al. New insights into the mechanisms of vitamin D action. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:695–705. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1689S–1696S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerner SA, et al. Sequence elements in the human osteocalcin gene confer basal activation and inducible response to hormonal vitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4455–4459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohyama Y, et al. Functional assessment of two vitamin D-responsive elements in the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30381–30385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton AL, MacDonald PN. Vitamin D: more than a “bone-a-fide” hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:777–791. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna NJ, et al. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oda Y, et al. Two distinct coactivators, DRIP/mediator and SRC/p160, are differentially involved in vitamin D receptor transactivation during keratinocyte differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2329–2339. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:551–561. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Is fall prevention by vitamin D mediated by a change in postural or dynamic balance? Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:656–663. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demay MB, et al. Sequences in the human parathyroid hormone gene that bind the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and mediate transcriptional repression in response to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8097–8101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin KJ, Gonzalez EA. Vitamin D analogs: actions and role in the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Seminars in nephrology. 2004;24:456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canaff L, Hendy GN. Human calcium-sensing receptor gene. Vitamin D response elements in promoters P1 and P2 confer transcriptional responsiveness to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30337–30350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vieth R, et al. Age-related changes in the 25-hydroxyvitamin D versus parathyroid hormone relationship suggest a different reason why older adults require more vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:185–191. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadowaki S, Norman AW. Demonstration that the vitamin D metabolite 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 and not 24R,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 is essential for normal insulin secretion in the perfused rat pancreas. Diabetes. 1985;34:315–320. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and pancreatic beta-cell function: vitamin D receptors, gene expression, and insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1602–1610. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.4.8137721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittas AG, et al. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2017–2029. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knekt P, et al. Serum vitamin D and subsequent occurrence of type 2 diabetes. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2008;19:666–671. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318176b8ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolek OI, et al. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link in a renal-gastrointestinal-skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G1036–1042. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF23 is a hormone-regulating phosphate metabolism--unique biological characteristics of FGF23. Bone. 2007;40:1190–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The HYP Consortium. Nat Genet. 1995;11:130–136. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White KE, et al. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat Genet. 2000;26:345–348. doi: 10.1038/81664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Econs MJ, Drezner MK. Tumor-induced osteomalacia--unveiling a new hormone. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Topaz O, et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:579–581. doi: 10.1038/ng1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benet-Pages A, et al. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:385–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li YC, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the reninangiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:229–238. doi: 10.1172/JCI15219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiang W, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy in vitamin D receptor knockout mice: role of the systemic and cardiac renin-angiotensin systems. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E125–132. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00224.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giovannucci E, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168:1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forman JP, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, et al. Combination therapy with AT1 blocker and vitamin D analog markedly ameliorates diabetic nephropathy: blockade of compensatory renin increase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15896–15901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803751105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sigmundsdottir H, et al. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to ‘program’ T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nature immunology. 2007;8:285–293. doi: 10.1038/ni1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, et al. Modulatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human B cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2007;179:1634–1647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bikle D. Vitamin D and Immune Function: Understanding Common Pathways. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2009:7. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigby WF, et al. Inhibition of T lymphocyte mitogenesis by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol). J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1451–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI111557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lemire JM, et al. Immunosuppressive actions of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: preferential inhibition of Th1 functions. J Nutr. 1995;125:1704S–1708S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_6.1704S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel C, et al. Immune modulatory treatment of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis with calcitriol is associated with a change of a T helper (Th) 1/Th17 to a Th2 and regulatory T cell profile. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2008;324:23–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bettelli E, et al. Induction and effector functions of T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;453:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature07036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boonstra A, et al. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4974–4980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penna G, Adorini L. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffin MD, et al. Vitamin D and its analogs as regulators of immune activation and antigen presentation. Annual review of nutrition. 2003;23:117–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adorini L. Intervention in autoimmunity: the potential of vitamin D receptor agonists. Cellular immunology. 2005;233:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adorini L, et al. Prevention of chronic allograft rejection by Vitamin D receptor agonists. Immunology letters. 2005;100:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kragballe K, et al. Double-blind, right/left comparison of calcipotriol and betamethasone valerate in treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Lancet. 1991;337:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92157-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Z, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin overproduced by keratinocytes in mouse skin aggravates experimental asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1536–1541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812668106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehrchen J, et al. Vitamin D receptor signaling contributes to susceptibility to infection with Leishmania major. Faseb J. 2007;21:3208–3218. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7261com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Litonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;120:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu PT, et al. Therapeutic implications of the TLR and VDR partnership. Trends in molecular medicine. 2007;13:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gombart AF, et al. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Faseb J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang TT, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ustianowski A, et al. Prevalence and associations of vitamin D deficiency in foreign-born persons with tuberculosis in London. J Infect. 2005;50:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schauber J, et al. Control of the innate epithelial antimicrobial response is cell-type specific and dependent on relevant microenvironmental stimuli. Immunology. 2006;118:509–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ingraham BA, et al. Molecular basis of the potential of vitamin D to prevent cancer. Current medical research and opinion. 2008;24:139–149. doi: 10.1185/030079908x253519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palmer HG, et al. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:369–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah S, et al. Trans-repression of beta-catenin activity by nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48137–48145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah S, et al. The molecular basis of vitamin D receptor and beta-catenin crossregulation. Mol Cell. 2006;21:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dixon KM, et al. Skin cancer prevention: a possible role of 1,25dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta R, et al. Photoprotection by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 is associated with an increase in p53 and a decrease in nitric oxide products. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:707–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giovannucci E. Vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:31–42. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gorham ED, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;32:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:684–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertone-Johnson ER, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1991–1997. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ahn J, et al. Serum vitamin D concentration and prostate cancer risk: a nested case-control study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:796–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lappe JM, et al. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beer TM, et al. Double-blinded randomized study of high-dose calcitriol plus docetaxel compared with placebo plus docetaxel in androgen-independent prostate cancer: a report from the ASCENT Investigators. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:669–674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parfitt AM. Vitamin D and the Pathogenesis of Rickets and Osteomalacia. Elsevier. 2005;2:1029–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:842–856. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heaney RP, et al. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:204–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hathcock JN, et al. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:6–18. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]