Summary

Thymus-derived naturally occurring regulatory T cells (nTregs) are necessary for immunological self-tolerance. nTreg development is instructed by the T cell receptor, and can be induced by agonist antigens that trigger T cell negative selection. How T cell deletion is regulated so that nTregs are generated is unclear. Here we showed that transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling protected nTregs and antigen-stimulated conventional T cells from apoptosis. Enhanced apoptosis of TGF-β receptor-deficient nTregs was associated with high expression of pro-apoptotic proteins Bim, Bax, and Bak, and low expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. Ablation of Bim in mice corrected the Treg development and homeostasis defects. Our results suggest that nTreg commitment is independent of TGF-β signaling. Instead, TGF-β promotes nTreg survival by antagonizing T cell negative selection. These findings reveal a critical function for TGF-β in control of autoreactive T cell fates with important implications for understanding T cell self-tolerance mechanisms.

Introduction

The stochastic process by which T cell antigen receptors (TCRs) are generated produces T cells bearing TCRs with high affinity for self-antigens. Both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic mechanisms have evolved to control pathogenic autoreactive T cells. T cells encountering high affinity self-antigens in the thymus can be eliminated through apoptosis (negative selection), which is mediated in part by the pro-apoptotic molecule Bim (Bouillet et al., 2002; Hogquist et al., 2005; Mathis and Benoist, 2004; Palmer, 2003). In addition, regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 are required to keep in check the autoreactive T cells that evade negative selection (Feuerer et al., 2009; Josefowicz and Rudensky, 2009; Sakaguchi et al., 2008; Shevach, 2009).

Thymic differentiation of naturally occurring CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs (nTregs) is regulated by TCR affinity. Studies with TCR transgenic mouse models reveal that engagement of agonist self-peptides induces not only T cell negative selection but also nTreg differentiation (Apostolou et al., 2002; Jordan et al., 2001; Kawahata et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2003). The mechanisms by which nTregs are protected from clonal deletion are unclear. nTregs or their precursors might be inherently more resistant to negative selection than conventional T cells (van Santen et al., 2004). The magnitude of clonal deletion may also be regulated so that large numbers of nTregs are produced to suppress autoreactive T cells. How TCR signaling is integrated to the differentiation program of nTregs, which culminates in the stable expression of Foxp3, also remains incompletely understood. However, additional signals from costimulatory receptors such as CD28 and cytokines including the common γ-chain cytokines appear essential for the lineage commitment of nTregs (Burchill et al., 2007; Fontenot et al., 2005; Malek et al., 2002; Salomon et al., 2000; Tai et al., 2005; Vang et al., 2008).

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a regulatory cytokine with pleiotropic functions in control of T cell responses (Li and Flavell, 2008). TGF-β1-deficient mice or mice with T cell-specific deletion of TGF-β receptors develop early fatal multifocal inflammatory diseases, highlighting a pivotal role for TGF-β in T cell tolerance. How TGF-β regulates T cell tolerance and its interactions with other self-tolerance pathways including T cell negative selection and Treg-mediated suppression have yet to be clarified. Activation of naïve T cells in the presence of TGF-β induces Foxp3 expression, and the differentiation of induced Tregs (iTregs) (Chen et al., 2003; Kretschmer et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2004). In contrast to the thymic origin of nTregs, iTregs are differentiated in the periphery, and they may control immune tolerance to innocuous environmental antigens such as those derived from commensal flora (Curotto de Lafaille and Lafaille, 2009). TGF-β-induced iTreg differentiation is in part mediated by the recruitment of its downstream transcription factor Smad3 to a Foxp3 enhancer element and the consequent induction of Foxp3 gene expression (Tone et al., 2008).

The function of and mechanism by which TGF-β controls nTreg differentiation and homeostasis remain ill-defined. Studies using mice with T cell-specific deletion of the TGF-β type II receptor (Tgfbr2) gene showed that TGF-β signaling is dispensable for the development of nTregs in 12–16-day-old mice (Li et al., 2006; Marie et al., 2006). A recent report, however, revealed an earlier requirement for TGF-β signaling in nTreg development. Conditional deletion of the TGF-β type I receptor (Tgfbr1) gene in T cells blocks thymic nTreg differentiation in 3–5-day-old mice but triggers nTreg expansion in mice older than 1 week (Liu et al., 2008). It was postulated that TGF-β signaling was required for the induction of Foxp3 gene expression and nTreg lineage commitment in neonatal mice similar to iTregs (Liu et al., 2008). The later expansion, a phenomenon also observed in mice deficient in TGF-βRII, was explained by the enhanced nTreg proliferation in response to increasing amounts of the cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008). Despite uncompromised thymic production of nTregs in 12–16-day-old TGF-β receptor-deficient mice, Tregs are reduced in the peripheral lymphoid organs of these mice, concomitant with the induction of rampant inflammatory diseases (Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008; Marie et al., 2006). The mechanisms by which TGF-β maintains peripheral Tregs remain to be determined.

In this study, using a T cell-specific TGF-βRII-deficient mouse model, we found that TGF-β signaling protected thymocytes from negative selection. In addition, TGF-β signaling inhibited nTreg apoptosis that was associated with imbalanced expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Genetic ablation of the pro-apoptotic molecule Bim rescued nTreg death, and restored the number of thymic nTregs in TGF-βRII-deficient mice. Bim deficiency also corrected the Treg homeostasis defects, attenuated T cell activation and differentiation, and prolonged the lifespan of TGF-βRII-deficient mice. These observations revealed a crucial function for TGF-β in inhibiting T cell negative selection and nTreg apoptosis. This function was discrete from TGF-β induction of Foxp3 expression and iTreg differentiation. These findings also showed that T cell TGF-β signaling was essential for the survival of peripheral Tregs, and for the inhibition of autoreactive T cells. Collectively, our results demonstrate that TGF-β hinders deletional tolerance, but promotes immune suppression to control T cell autoreactivity.

Results

Enhanced Anti-CD3-induced T Cell Apoptosis in the Absence of TGF-β Signaling

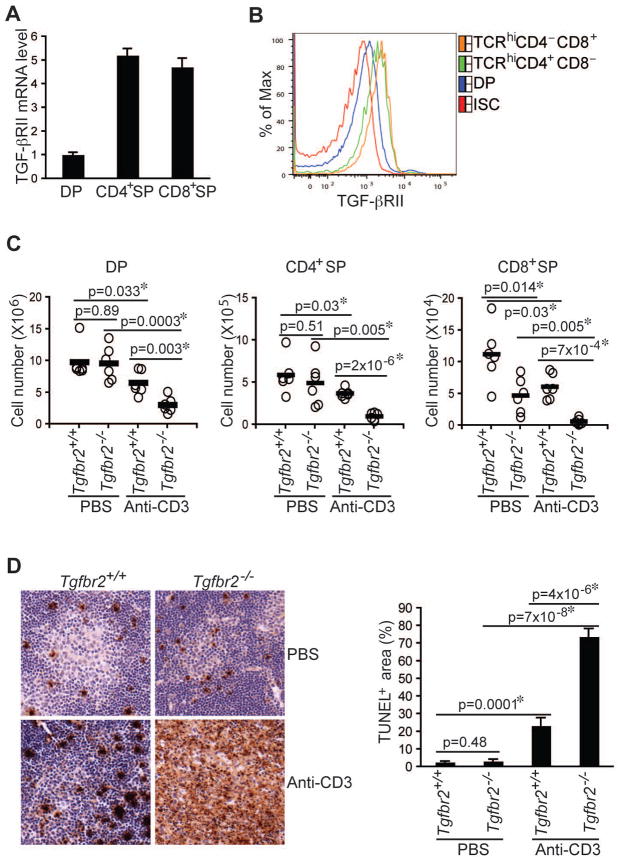

Among the numerous properties of TGF-β in the immune system is its ability to control T cell tolerance (Li and Flavell, 2008). We sought to investigate how T cell responses to high affinity self-antigens are modulated by TGF-β signaling transduced by TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII receptors. To determine whether TGF-β receptor expression is regulated during T cell development, we examined mRNA expression in immature CD4+CD8+ and mature TCR-βhiCD4+ and TCR-βhiCD8+ thymocytes. mRNA encoding the ligand-binding receptor TGF-βRII, but not TGF-βRI, showed approximately 5-fold higher expression in mature T cells than in immature T cells (Figure 1A and data not shown), which was associated with the enhanced TGF-βRII protein expression (Figure 1B and Figure S1A). These observations suggested that TGF-βRII-dependent signaling might regulate T cell selection.

Figure 1. Enhanced Anti-CD3-induced T Cell Apoptosis in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice.

(A, B) TGF-βRII expression in CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), CD4+CD8− single positive (CD4+SP) and CD4−CD8+ (CD8+SP) thymocytes was determined by quantitative PCR (A) and Flow cytometric analysis (B). ISC stands for iso-type control.

(C, D) Four-day-old wild-type (Tgfbr2+/+) and TGF-βRII-deficient (Tgfbr2−/−) mice were intraperitoneally injected with PBS or 20 μg/mouse of anti-CD3. Cell numbers of DP, CD4+SP, and CD8+SP thymocytes were determined 24 hr after the injection (C, n=6). Thymocyte apoptosis was examined by TUNEL staining 48 hr after the injection (D, left panel, original magnification, 20×). TUNEL staining-positive area of 4 sections per group was quantified by MetaMoph software (D, right panel). Data are representative of two (A) and three (B–D) independent experiments. The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

Thymocytes bearing high affinity TCRs for self-antigens undergo clonal deletion or negative selection, which provides an important mechanism for the prevention of autoimmunity (Hogquist et al., 2005; Mathis and Benoist, 2004; Palmer, 2003). To determine whether TGF-βRII is required for clonal deletion, we used a T cell-specific TGF-βRII-deficient (Tgfbr2−/−) mouse model generated by crossing a strain of floxed Tgfbr2 mice with the CD4-Cre transgene (Li et al., 2006). Using these mice, we and others have shown that TGF-βRII-dependent signaling is essential for the maintenance of T cell tolerance (Li et al., 2006; Marie et al., 2006), but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Neonatal 4-day-old wild-type (Tgfbr2+/+) and Tgfbr2−/− mice were injected with either PBS or CD3 antibody to model high affinity TCR ligation. 24 hr later, thymi from these mice were collected, and the immature and mature T cells were enumerated. As expected, T cell numbers from Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2+/+ mice in the PBS control group were comparable with the exception of a 50% reduction of TCR-βhiCD8+ T cells in Tgfbr2−/− mice as previously reported (Li et al., 2006) (Figure 1C). Surprisingly, thymocytes, notably TCR-βhiCD4+ and TCR-βhiCD8+ mature T cell subsets, were more profoundly depleted in Tgfbr2−/− mice administrated with CD3 antibody (Figure 1C). Enhanced T cell deletion was associated with a 3-fold increase in the size of apoptotic areas in tissue sections from the thymi of Tgfbr2−/− mice detected by TUNEL staining (Figure 1D). Therefore, intact TGF-β signaling appeared to be required to protect T cells from anti-CD3-induced T cell apoptosis.

Most peripheral T cells from 4-day-old Tgfbr2−/− mice manifested a naïve CD44loCD62Lhi phenotype similar to T cells from Tgfbr2+/+ mice (data not shown). However, CD3 antibody might activate these T cells, and trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and stress hormone that could obscure TCR-induced deletion of thymocytes (Brewer et al., 2002). To avoid the potential complication of peripheral T cells, we isolated thymocytes from Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2+/+ mice, and cultured them with CD3 and CD28 antibodies for 24 hr. Subsequently, apoptotic cells in culture were assessed with annexin V staining. Compared to T cells from Tgfbr2+/+ mice, increased apoptosis was observed in TCR-βhiCD4+ and TCR-βhiCD8+ T cells from Tgfbr2−/− mice (Figures S1B and S1C). These observations supported a direct role for TGF-β signaling in inhibiting anti-CD3-induced T cell apoptosis.

Exaggerated T Cell Negative Selection in the Absence of TGF-β Signaling

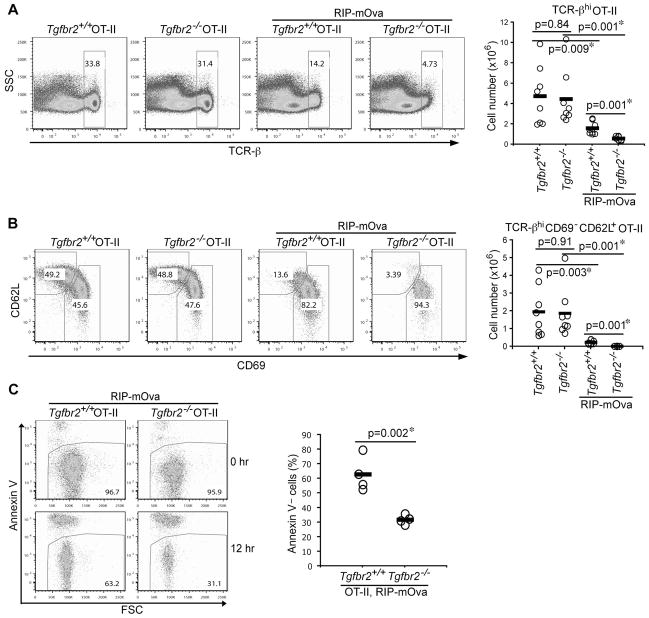

To determine a definitive function for TGF-β in control of antigen-induced T cell negative selection, we used a TCR transgenic mouse model. OT-II (CD4+ TCR specific for an ovalbumin peptide) transgenic mice were crossed to the RIP-mOVA transgene driving expression of a membrane-bound form of ovalbumin (mOVA) under the control of a rat insulin promoter (RIP) (Kurts et al., 1996). In addition to mOVA expression in the pancreatic β cells, mOVA is expressed in the medullary thymic epithelial cells, leading to a pronounced thymic deletion of OT-II T cells (Anderson et al., 2005; Gallegos and Bevan, 2004). OT-II mice were further crossed onto Rag1−/− background to prevent the rearrangement of endogenous TCR that may alter T cell antigen specificity.

In line with our previous observations (Li et al., 2006), TGF-βRII deficiency did not affect OT-II T cell positive selection in the absence of mOVA expression (Figures 2A and 2B). However, thymic deletion of TCR-βhi OT-II T cells was markedly enhanced in 5-week-old Tgfbr2−/− mice on RIP-mOVA background (Figure 2A), which was associated with a profound reduction of mature CD69−CD62L+ OT-II T cells (Figure 2B). Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOVA mice started to develop diabetes at 6 weeks of age (see below). It was possible that T cell negative selection may be affected by diabetes-induced stress in week-old mice. To minimize this effect, we determined T cell deletion in 8-day-old mice. Diminished TCR-βhi and mature CD69−CD62L+ OT-II T cells were similarly observed in Tgfbr2−/− RIP-mOVA mice (Figure S2A). To directly assess T cell survival potential, thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells were isolated from Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2+/+ RIP-mOVA mice by FACS sorting, and cultured in medium for 12 hr. Compared to Tgfbr2+/+ OT-II T cells, approximately 50% viable Tgfbr2−/− OT-II T cells were recovered (Figure 2C). Taken together, these findings revealed an unexpected function for TGF-β signaling in protecting T cells from antigen-induced negative selection.

Figure 2. Exaggerated T cell Negative Selection in the absence of TGF-β Signaling.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of TCR-β expression in thymic OT-II T cells from 5-week-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene (left panel). The numbers of thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells from 8 groups of mice are shown (right panel).

(B) Flow cytometric analysis of CD69 and CD62L expression in thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells from 5-week-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene (left panel). The numbers of thymic TCR-βhiCD69−CD62L+ OT-II T cells from 8 groups of mice are shown (right panel).

(C) Survival of thymic OT-II T cells from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. Thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells were purified by FACS sorting, and cultured for 12 hr. T cell viability before and after the cell culture was determined by annexin V staining (left panel). Percentages of viable T cells at 12 hr from 4 pairs of mice are presented (right panel). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

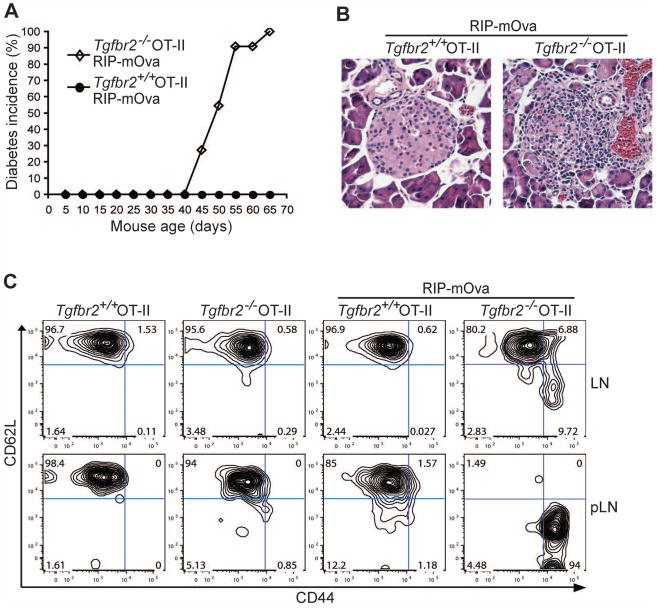

TGF-β Control of Peripheral T Cell Tolerance to a Neo-self Antigen

Mice with T cell-specific deletion of TGF-β receptors develop fatal systemic inflammatory diseases on a polyclonal T cell background, which is associated with widespread T cell activation (Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008; Marie et al., 2006). However, studies with TCR-transgenic mouse models reveal that most TGF-β receptor-deficient T cells specific for foreign antigens exhibit a naïve T cell phenotype (Li et al., 2006; Marie et al., 2006). We wished to investigate whether cognate antigen stimulation was required for T cell hyperactivation in the absence of TGF-β signaling. To this end, we first determined whether TGF-βRII deficiency would affect T cell tolerance in OT-II RIP-mOVA mice. Consistent with previous reports (Anderson et al., 2005; Gallegos and Bevan, 2004), wild-type OT-II RIP-mOVA mice were tolerized to the ovalbumin antigen, and remained diabetes free for at least 8 months (Figure 3A and data not shown). In striking contrast, 6-week-old Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOVA mice started to develop diabetes, and all mice became diabetic by 10 weeks of age (Figure 3A). Histological analysis of tissue sections from TGF-βRII-deficient, but not wild-type OT-II RIP-mOVA mice revealed an aggressive leukocyte infiltrate in the islets of the pancreas (Figure 3B). In line with these observations, TGF-βRII-deficient but not wild-type OT-II T cells isolated from the pancreatic draining lymph nodes, displayed an activated CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype (Figure 3C). However, most Tgfbr2−/− OT-II T cells from the non-pancreatic draining lymph nodes of RIP-mOVA mice, which presumably had not been exposed to mOVA antigen, exhibited a CD44loCD62Lhi naïve T cell phenotype (Figure 3C). These observations demonstrated that despite enhanced T cell negative selection in the absence of T cell TGF-β signaling, an intact TGF-β pathway was essential for the inhibition of antigen-induced T cell activation, and for the maintenance of peripheral T cell tolerance.

Figure 3. Diabetes Development and T cell Activation in TGF-βRII-deficient OT-II RIP-mOva Mice.

(A) The incidence of diabetes in Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOva mice (n=11).

(B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the pancreas of 8-week-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOva mice (original magnification, 20×). These are representative results of four mice per group analyzed.

(C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD44 and CD62L expression in OT-II T cells from non-pancreatic control lymph nodes (LN) and pancreatic lymph nodes (pLN) of 5-week-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

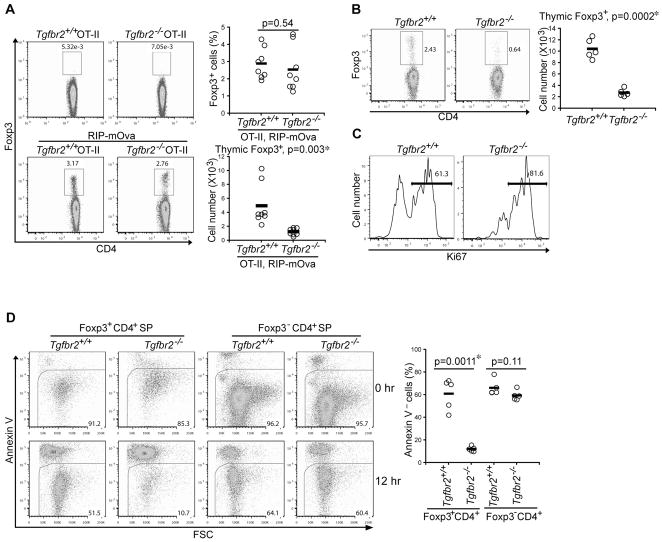

Increased Thymic nTreg Death in the Absence of TGF-β Signaling

In addition to T cell negative selection, thymic generation of nTregs is essential for the establishment of immunological self-tolerance (Feuerer et al., 2009; Josefowicz and Rudensky, 2009; Sakaguchi et al., 2008; Shevach, 2009). Using TCR transgenic mice that express the cognate antigens in the thymus, it has been shown that nTregs can be generated in response to TCR agonist ligand stimulation (Apostolou et al., 2002; Jordan et al., 2001; Kawahata et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2003). To investigate whether TGF-β signaling regulates nTreg differentiation, we determined the frequency and number of thymic nTregs in OT-II mice. In the absence of mOVA, nTregs were barely detectable in either Tgfbr2+/+ or Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice (Figure 4A and Figure S2B). On the RIP-mOVA background, 1–5% TCR-βhi OT-II T cells differentiated into Foxp3+ nTregs in Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice (Figure 4A and Figure S2B). However, as a consequence of enhanced mOVA antigen-induced T cell deletion (Figure 2), the numbers of both Foxp3+ nTregs and Foxp3− mature T cells from Tgfbr2−/− mice were reduced to approximately 25% of those from Tgfbr2+/+ mice (Figure 4A and data not shown). A recent study showed that nTreg development is compromised in neonatal mice with a T cell-specific inactivation of TGF-βRI, which was postulated to be caused by defective Foxp3 induction (Liu et al., 2008). Because we observed similar frequencies of nTregs in Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2+/+ OT-II RIP-mOVA mice (Figure 4A and Figure S2B), we hypothesized that nTreg survival, rather than its lineage commitment, was dependent on TGF-β signaling.

Figure 4. TGF-β Control of Thymic nTreg Survival.

(A) Thymic nTregs from 5-week-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence RIP-mOva transgene. Foxp3 expression in TCR-βhi OT-II T cells (left panel), and the percentages (right top panel) and numbers (right bottom panel) of nTregs from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOva mice are shown (n=8).

(B) Thymic nTregs in 3–5-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. Foxp3 expression in TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells (left panel), and nTreg numbers from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice (right panel) are shown (n=5).

(C) Flow cytometric analysis of Ki67 expression in thymic nTregs from 3–5-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. These are representative results of four mice per group analyzed.

(D) Thymic Foxp3+CD4+ single positive (SP) nTregs and Foxp3−CD4+ SP conventional T cells were purified by FACS sorting from 14–16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice, and cultured for 12 hr. T cell viability before and after the cell culture was determined by annexin V staining (left panel). Percentages of viable T cells at 12 hr from 5 pairs of mice are presented (right panel). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

We tested this hypothesis using Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice on a polyclonal T cell background. Consistent with the previous report (Liu et al., 2008), the number of thymic nTregs in 3–5-day-old Tgfbr2−/− mice was about 25% of that in Tgfbr2+/+ mice (Figure 4B). The numbers of TCR-βhiCD4+Foxp3− conventional T cells were comparable between Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2+/+ mice (data not shown), most of which were likely low affinity TCR T cells that had undergone positive selection. A higher proportion of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs expressed the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 than Tgfbr2+/+ nTregs (Figure 4C), suggesting that reduction of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs was not caused by defective cell division. To directly assess T cell survival potential, we purified thymic nTregs and conventional TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells based on the expression of Foxp3 marked by a red-fluorescent protein (Wan and Flavell, 2005). Whereas Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− conventional T cells, and Tgfbr2+/+ nTregs had a comparable survival rate, 5-fold more Tgfbr2−/− nTregs underwent cell death after a 12 hr culture (Figure 4D). Reduced numbers of viable Tgfbr2−/− nTregs were observed as early as 6 hr after in vitro culture (Figure S3A). These observations revealed that concomitant with TGF-β inhibition of T cell negative selection, TGF-β signaling promoted survival of thymic nTregs.

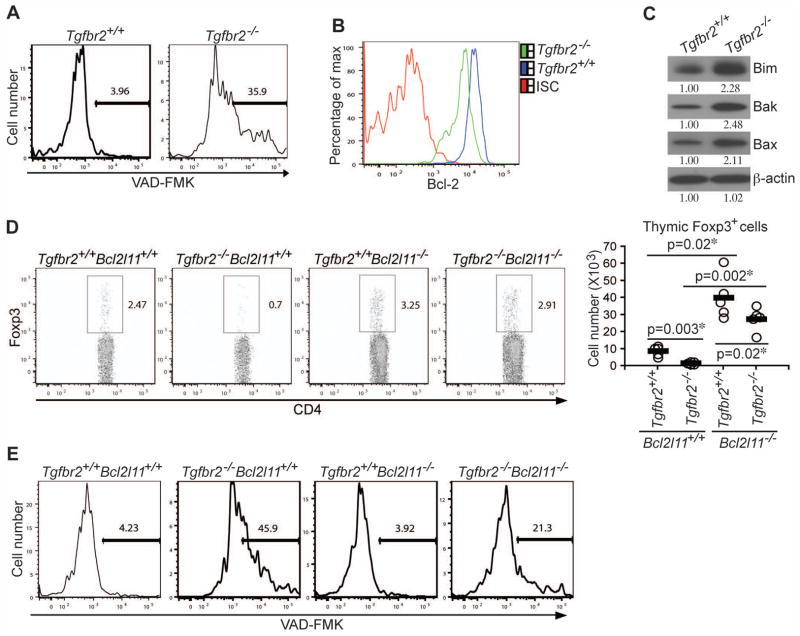

Bim Regulation of nTreg Apoptosis in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice

We next sought to investigate the mechanisms underlying the exaggerated cell death of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs. Deletion of autoreactive T cells occurs through apoptosis (Smith et al., 1989), which is mediated by the cysteine proteases, caspases (Lakhani et al., 2006). Approximately 10-fold more Tgfbr2−/− nTregs exhibited high caspase activity than Tgfbr2+/+ nTregs isolated from 3–5-day-old mice (Figure 5A), supporting an apoptotic mechanism of cell death. As previously reported (Li et al., 2006; Marie et al., 2006), the frequency of thymic nTregs in 16-day-old Tgfbr2−/− mice was no less than that of the control mice (Figure S3B). Importantly, elevated caspase activation was also detected in nTregs from 16-day-old Tgfbr2−/− mice (Figure S3C). Recovery of thymic nTregs in these mice was likely due to the long-lasting enhanced nTreg proliferation (Figure 4C and Figure S3D). These findings demonstrated that TGF-β signaling was essential for inhibiting caspase activation and nTreg apoptosis in neonatal as well as week-old mice.

Figure 5. TGF-β Signaling Regulates Thymic nTreg Development via the Inhibition of Bim-dependent Apoptosis.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of caspase activation in 4-day-old thymic nTregs from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. These are representative results of four mice per group analyzed.

(B) Flow cytometric analysis of Bcl-2 expression in thymic nTregs from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. ISC stands for the isotype control antibody.

(C) The expression of Bim, Bak, and Bax in thymic nTregs from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice was determined by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a protein-loading control. Band densities were quantified by ImageJ. The relative protein amounts are shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

(D) Restoration of thymic nTreg development in Tgfbr2−/− mice by Bim deletion. Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells from 4-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice (left panel), and nTreg numbers from 5 groups of 3–5-day-old mice are presented (right panel). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

(E) Flow cytometric analysis of caspase activation in thymic nTregs from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

Signals from the common γ-chain cytokines, including IL-2, IL-15, and IL-7, are important regulators of T cell survival and nTreg differentiation (Burchill et al., 2007; Fontenot et al., 2005; Malek et al., 2002; Vang et al., 2008). To investigate whether compromised survival of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs was due to defective signaling of IL-2, IL-15, or IL-7, we determined thymic expression of these cytokines and the cytokine receptors. With the exception of CD127 (IL-7 receptor α chain), the amounts of CD25 (IL-2 receptor α chain), CD122 (the shared IL-2 and IL-15 β chain), and CD132 (the common γ chain) were all elevated in Tgfbr2−/− nTregs (Figure S4A), whereas the amounts of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 mRNA were comparable in the thymi of Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice (Figure S4B). To explore a potential role for the reduced CD127 expression in Tgfbr2−/− nTregs, we crossed Tgfbr2−/− mice with a strain of IL-7R transgenic mice (Park et al., 2004). However, restoration of CD127 expression did not correct the reduced frequency of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs in 3–5-day-old mice (Figures S4C and S4D). These observations suggested that nTreg apoptosis in Tgfbr2−/− mice was unlikely caused by the compromised signaling of common γ-chain cytokines.

A prominent pathway of caspase activation and induction of apoptosis is through permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane, which is regulated by proteins of the Bcl-2 family including both the prosurvival protein Bcl-2 and the proapoptotic proteins such as Bim, Bak, and Bax (Bouillet et al., 2002; Rathmell et al., 2002; Youle and Strasser, 2008). Associated with the enhanced caspase activation in Tgfbr2−/− nTregs, Bcl-2 expression was downregulated (Figure 5B), whereas the expression of Bim, Bak, and Bax proteins was upregulated (Figure 5C). Previous studies have established Bim as a key regulator of T cell apoptosis during negative selection (Bouillet et al., 2002). Indeed, Bim deficiency corrected the enhanced OT-II T cell deletion in Tgfbr2−/− RIP-mOVA mice (Figures 2A, 2B, and Figures S2C, S2D). To determine whether the elevated Bim expression was causative for the enhanced apoptosis of Tgfbr2−/− nTregs, we crossed Tgfbr2−/− mice to the Bim-deficient (Bcl2l11−/−) background. The frequency and number of thymic Tgfbr2−/− nTregs from 3–5-day-old mice were corrected by 80% in the absence of Bim (Figure 5D), which was associated with decreased caspase activation (Figure 5E). It is noteworthy that Bim deficiency itself caused a general increase of thymic nTregs (Figure 5D and Figure S5A), which was likely a consequence of reduced T cell negative selection (Bouillet et al., 2002). CD28 costimulation is essential for nTreg development, which is possibly through CD28 regulation of Foxp3 gene expression (Salomon et al., 2000; Tai et al., 2005). Importantly, Bim deletion did not rescue the thymic nTreg defects in CD28-deficient mice (Figure S5B). These observations suggested that TGF-β signaling played a specific role in protecting nTregs from Bim-dependent apoptosis, and was unlikely involved in the induction of Foxp3 expression in nTregs.

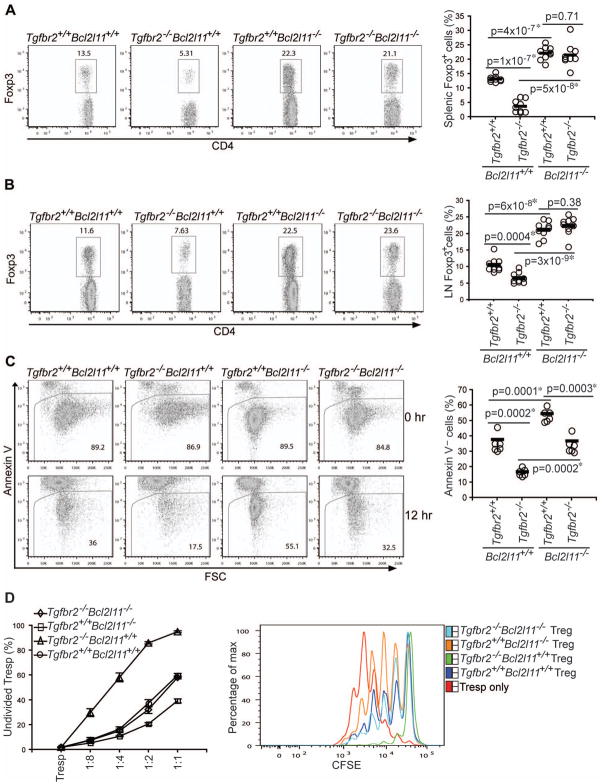

Bim Control of Treg Homeostasis and T Cell Activation in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice

Tregs fail to be maintained in the peripheral lymphoid organs of TGF-β receptor-deficient mice (Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008; Marie et al., 2006), but the underlying mechanisms have yet to be characterized. To determine whether Bim-dependent apoptosis accounted for this defect, we examined peripheral Tregs in mice deficient in both TGF-βRII and Bim (Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/−). Whereas the frequency of splenic and lymph node Tregs from Tgfbr2−/− mice was lower than that from Tgfbr2+/+ mice, an almost complete rescue of the proportion of Tregs was observed in Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice (Figures 6A, 6B, and Figure S5C). Reduced Tregs in Tgfbr2−/− mice were associated with an approximate 2-fold increase of Treg apoptosis, which was corrected by 60% in the absence of Bim (Figure 6C). Notably, Bim deletion did not rescue the peripheral Treg defects in CD28-deficient mice (Figure S5B). These observations revealed a specific function for TGF-β signaling in protecting peripheral Tregs from mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis.

Figure 6. Bim Ablation Restores Peripheral Tregs in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice.

(A, B) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression in splenic (A) and lymph node (LN) (B) CD4+ T cells from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice (left panels). Treg percentages from 8 groups of 14–16-day-old mice are shown (right panels).

(C) Splenic and lymph node Tregs were purified from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/− and Tgfbr2−/− Bcl2l11−/− mice by FACS sorting, and cultured for 12 hr. T cell viability before and after the cell culture was determined by annexin V staining (left panel). Percentages of viable T cells at 12 hr from 6 groups of 14–16-day-old mice are presented (right panel). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

(D) Suppressive function of Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− Tregs. Splenic and lymph node Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs were isolated from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. CD44loCD4+ T cells from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+ mice were labeled with CFSE, and used as responding T cells (Tresp). Cell division was assessed by CFSE dilution. The percentages of undivided Tresp cells (Y axis) and the ratios of cell numbers between Treg and Tresp cells (X axis) were plotted (left panel). A representative of CFSE dilution of Tresp cells cultured in the absence or presence of 1:2 ratio of Tregs to Tresp cells was shown (right panel). These are representative of three independent experiments.

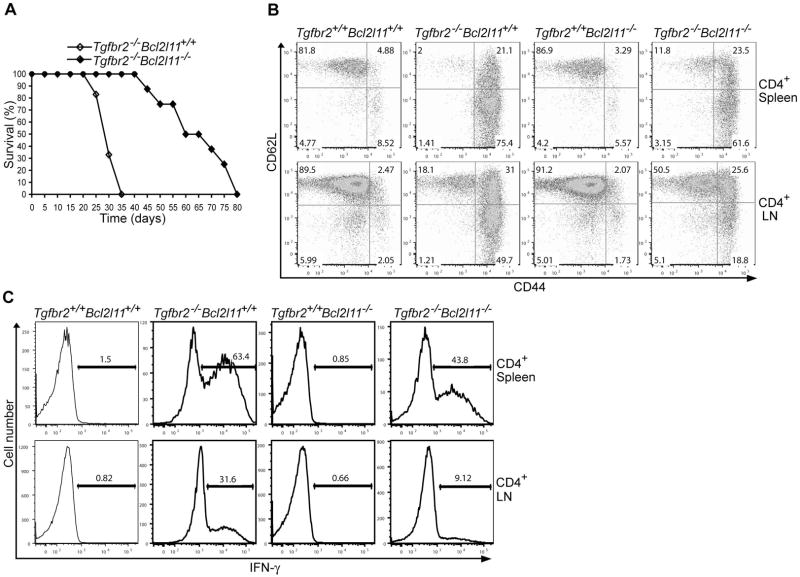

To determine the effects of Bim deficiency on the anergic phenotype of Tregs and Treg suppressive function, we used CFSE-based cell proliferations assays. Whereas wild-type or Bcl2l11−/− Tregs were refractory to anti-CD3-induced proliferation, Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− Tregs underwent substantial cell division (Figure S5D). Compared to wild-type Tregs, Tgfbr2−/− Tregs had enhanced suppressive activity on a per cell basis, whereas Bcl2l11−/− Tregs were less suppressive (Figure 6D). Importantly, Tgfbr2−/− Bcl2l11−/− Tregs had comparably suppressive activity to wild-type Tregs (Figure 6D). To investigate the impact of Bim deficiency on peripheral T cell tolerance, we examined the lifespan of Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. Whereas 100% Tgfbr2−/− mice died by 5 weeks of age, all Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice survived during the same period (Figure 7A). Compared to CD4+ T cells from Tgfbr2−/− mice, a smaller proportion of CD4+ T cells from Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice exhibited an activated CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype (Figure 7B), and fewer CD4+ T cells produced the effector cytokine IFN-γ (Figure 7C). Nevertheless, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice eventually succumbed to a lethal multi-focal inflammatory disorder similar to that of Tgfbr2−/− mice (Figure 7A and Figure S6). These observations revealed that Bim rescue of peripheral Tregs was associated with a partial correction of the T cell activation and lethal autoimmune phenotype in Tgfbr2−/− mice.

Figure 7. Bim Ablation Partially Restores T Cell Tolerance in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice.

(A) Survival of Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+ (n=18) and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− (n=8) mice.

(B) Flow cytometric analysis of CD44 and CD62L expression in splenic and lymph node (LN) CD4+ T cells from 14-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. These are representative results of four mice per group analyzed.

(C) Splenic and LN CD4+ T cells from 14-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hr, and analyzed for the expression of IFN-γ by intracellular staining. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

Discussion

Although TGF-β has been established as a pivotal regulator of T cell tolerance, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. In this report, we used a T cell-specific TGF-βRII-deficient mouse strain to study the function of TGF-β signaling in control of T cell negative selection and nTreg development, two established pathways of T cell self-tolerance. Using anti-CD3-induced and antigen-triggered T cell deletion models, we found that thymic negative selection was repressed by TGF-β signaling in T cells. TGF-β inhibition of T cell deletion promoted thymic Treg survival, revealing a mechanism for TGF-β in regulation of nTreg development. Enhanced apoptosis of TGF-βRII-deficient nTregs was associated with high expression of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein Bim, lack of which partially rescued the nTreg cell death phenotype. In addition, we found that TGF-βRII-deficient Tregs in peripheral tissues underwent exaggerated Bim-dependent apoptosis; Bim deficiency restored peripheral Tregs, inhibited T cell activation, and extended the lifespan of T cell-specific TGF-βRII-deficient mice. These observations uncover previously undefined functions for TGF-β signaling in control of deletional tolerance and Treg-mediated immune suppression in vivo.

Autoreactive T cells can be readily found in the peripheral lymphoid organs of healthy individuals (Danke et al., 2004). In animal models of T cell negative selection, a large fraction of T cells also escape clonal deletion (Bouneaud et al., 2000). Lack of complete deletion of autoreactive T cells may be a consequence of limited expression and/or presentation of self-antigens in the thymus. Here we showed that negative selection was also actively suppressed by TGF-β signaling in T cells. Although the significance of this regulatory pathway remains to be fully elucidated, we found that by inhibiting T cell clonal deletion, TGF-β enhanced nTreg production. nTregs exhibit an ‘antigen-experienced’ phenotype, suggesting that their differentiation process is induced or accompanied by exposure to high-affinity self-antigens (Josefowicz and Rudensky, 2009; Sakaguchi et al., 2008). Recent studies of transgenic mice expressing TCRs derived from Tregs demonstrate that nTreg differentiation is indeed instructed by TCR specificity (Bautista et al., 2009; DiPaolo and Shevach, 2009; Leung et al., 2009). Intriguingly, the proportion of Treg-TCR transgenic T cells that mature into the Treg lineage is inversely correlated with the precursor frequency (Bautista et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2009), which could be explained by intraclonal competition for limited Treg-selecting high-affinity self MHC-peptide complexes. In one Treg-TCR transgenic mouse strain, profound T cell deletion was observed (DiPaolo and Shevach, 2009), revealing that at least some endogenous nTregs were differentiated in response to high affinity self-antigens. Consistent with these and previous studies (Apostolou et al., 2002; Jordan et al., 2001; Kawahata et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2003), co-expression of mOVA in OT-II transgenic mice triggered nTreg differentiation, concomitant with the induction of T cell negative selection. Blockade of TGF-β signaling in OT-II T cells resulted in heightened deletion of nTregs as well as conventional T cells in response to mOVA antigen. These observations are in line with the reports that Foxp3 deficiency does not affect the efficiency or sensitivity of T cell negative selection (Chen et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2006). Collectively, our findings suggest that nTregs are not inherently more resistant to apoptosis than conventional T cells, but the magnitude of T cell clonal deletion can be regulated to ensure proper production of nTregs.

The Treg-specific transcription factor Foxp3 can be induced in both developing thymocytes and peripheral T cells in response to appropriate combinations of TCR, costimulatory molecule, and cytokine stimulation (Josefowicz and Rudensky, 2009). Activation of peripheral naïve CD4+ T cells in the presence of TGF-β induces Smad-dependent Foxp3 expression and iTreg differentiation. Defective nTreg development had also been observed in neonatal mice with a T cell-specific inactivation of TGF-βRI, which was postulated to be caused by failed Foxp3 induction (Liu et al., 2008). Similar neonatal nTreg defects were present in TGF-βRII-deficient mice. However, we found that compromised differentiation of TGF-βRII-deficient nTregs was associated with high expression of the proapoptotic molecule Bim, enhanced caspase activation, and increased nTreg apoptosis. Importantly, genetic ablation of Bim restored nTregs in TGF-βRII-deficient mice. It is noteworthy that Bim deficiency did not correct the nTreg defects in mice lacking the costimulatory molecule CD28, the signals from which likely directly control Foxp3 gene transcription. These findings suggest that in contrast to iTregs, TGF-β signaling is not essential for the induction of Foxp3 expression in nTregs, but is required to inhibit Bim-dependent nTreg apoptosis.

The cellular and molecular mechanisms by which TGF-β regulates Bim expression and nTreg apoptosis are open for future studies. There are three types of TGF-β molecules in mammals, with TGF-β1 being the major protein expressed in the immune system (Li and Flavell, 2008). A previous report showed that T cells from TGF-β1-deficient mice are more susceptible to anti-CD3-induced T cell death, which was attributed to an intracellular function of TGF-β1 located in the mitochondrion (Chen et al., 2001). Because we found that TGF-βRII-deficient T cells were also hyper-sensitive to anti-CD3-induced apoptosis, TGF-β1 protection of T cell deletion was more likely mediated by the extracellular cytokine activity of TGF-β1. Whether TGF-β1 is involved in the inhibition of Bim expression and nTreg apoptosis has yet to be determined. In addition, multiple cell types produce TGF-β1 in vivo. Using a conditionally-deficient TGF-β1 mouse model, we have identified T cells as an essential source of TGF-β1 for control of T cell tolerance and effector T cell differentiation (Li et al., 2007). The functions of T cell or other cell type-produced TGF-β1 in control of nTreg survival will be an interesting topic for future study.

TGF-β engagement of the receptor complex initiates diverse signaling pathways that enable TGF-β to exert its pleiotropic functions (Li and Flavell, 2008). The signaling pathways involved in TGF-β inhibition of Bim expression in nTregs are unknown. Two recent reports using a transgenic mouse strain expressing a dominant-negative mutant of TGF-βRII (DNRII) in the T cell compartment revealed that TGF-β signaling promotes apoptosis of pathogen-specific CD8+ effector T cells (Sanjabi et al., 2009; Tinoco et al., 2009). In one study, decreased apoptosis of DNRII CD8+ T cells is associated with reduced Bim expression (Tinoco et al., 2009). It is currently unknown how TGF-β opposingly regulates Bim expression in nTregs and effector CD8+ T cells. We showed previously that the DNRII model, in contrast to the TGF-βRII conditional knockout mouse model used in this study, affords only a partial blockade of TGF-β signaling in T cells (Li et al., 2006), which might affect TGF-β regulation of Bim expression and T cell survival. It is also possible that TGF-β control of Bim expression is context dependent, with the ultimate effect being determined by the developmental stages of T cells and other environmental cues received by the T cells. It is noteworthy that Bim ablation did not completely rescue caspase activation in TGF-βRII-deficient mice. Other Bcl-2 family proteins including Bax, Bak, and Bcl-2 were dysregulated in TGF-βRII-deficient nTregs, raising the possibility that they might control Bim-independent caspase activation. How TGF-β regulates these and other alternative apoptosis pathways warrants further investigation.

Thymic nTregs from week-old TGF-βRII-deficient mice were equally susceptible to apoptosis as nTregs from neonatal mice. But thymic nTreg numbers were restored, which could be attributed to the enhanced cell proliferation. Nevertheless, the peripheral Treg numbers were reduced in TGF-βRII-deficient mice, revealing that intact TGF-β signaling was required for the maintenance of Tregs. In this study, we found that compromised Treg maintenance was caused by Bim-dependent Treg apoptosis. Interestingly, Bim deficiency not only restored peripheral Tregs, but also attenuated T cell activation, and prolonged the lifespan of TGF-βRII-deficient mice. These findings suggest that TGF-β inhibition of peripheral Treg apoptosis contributes to the maintenance of T cell self-tolerance. A recent study showed that Bim-deficient T cells are refractory to TCR-induced calcium responses (Ludwinski et al., 2009), raising the possibility that T cell-intrinsic defects might also contribute to the attenuated T cell activation and differentiation phenotype in Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. However, Bim ablation could not completely prevent the lethal inflammation developed in TGF-βRII-deficient mice. These observations are in line with the findings that Tregs are incapable of suppressing intestinal inflammation induced by naïve CD4+ T cells resistant to TGF-β signaling (Fahlen et al., 2005), and that transfer of wild-type Tregs to neonatal Tgfbr2−/− mice fails to correct the systemic autoimmune disease (Li et al., 2006). Therefore, in addition to the maintenance of peripheral Tregs, TGF-β signaling is indispensable for inhibiting autoreactive T cell activation and effector T cell differentiation.

In conclusion, in this report we have uncovered critical functions for TGF-β signaling in control of T cell negative selection, Treg development and homeostasis, and peripheral tolerance of autoreactive T cells. These findings refine and extend our understanding of T cell self-tolerance mechanisms, and may be exploited for the immunotherapy of autoimmune diseases in the future.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Mice containing floxed Tgfbr2, CD4-Cre, OT-II, Rag1−, RIP-mOva, Bcl2l11−, Il7rTg, CD28−, and Foxp3-RFP alleles were previously described (Bouillet et al., 2002; Kurts et al., 1996; Li et al., 2006; Park et al., 2004; Wan and Flavell, 2005). Foxp3-RFP mice were provided by R. Flavell (Yale). RIP-mOva and IL-7R transgenic mice were provided by W. Heath (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research) and A. Singer (National Cancer Institute) respectively. Bcl2l11−/−, CD28−/−, and Rag1−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice with two floxed Tgfbr2 alleles were used as controls (Tgfbr2+/+). T cell-specific TGF-βRII-deficient mice (Tgfbr2−/−) were generated by crossing Tgfbr2-floxed mice with the CD4-Cre transgene. Tgfbr2−/− and CD28−/− mice were crossed with Bcl2l11−/− mice to produce mice devoid of both genes (Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− and CD28−/−Bcl2l11−/−). Tgfbr2−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice were crossed with Foxp3-RFP mice to mark Tregs by red-fluorescent protein expression. OT-II RIP-mOva mice on a Rag1-deficient background were crossed with Tgfbr2−/− mice to generate Tgfbr2−/− OT-II RIP-mOva mice. Urine glucose concentrations in these mice were monitored by using Diastyx sticks (Bayer) on a weekly basis. Animals that had values of >250 mg/dl on two consecutive occasions were counted as diabetic. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Flow Cytometry

Fluorescent-dye-labeled antibodies against cell surface markers CD4, CD8, TCR-β, CD69, CD62L, CD44, CTLA4, GITR, ICOS, CD27, CD25, CD122, CD132, and CD127 were purchased from eBiosciences. Biotinylated mouse TGF-βRII antibody was obtained from R&D Systems. Thymic, splenic, and lymph node cells were depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis. Cells were incubated with specific antibodies for 15 min on ice in the presence of 2.4G2 mAb to block FcgR binding. All samples were acquired and analyzed with LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). Intracellular Foxp3, CTLA4, Ki67, and Bcl-2 stainings were carried-out with kits from eBiosciences and BD Biosciences. For intracellular cytokine staining, spleen and lymph node cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma), 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma) and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for 4 hr. After stimulation, cells were stained with cell surface marker antibodies, fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences), and stained with an IFN-γ antibody.

Immunoblotting

Thymic Foxp3+ Tregs marked by red-fluorescent protein expression were purified by FACS sorting. Protein extracts were prepared, separated on 15% SDS PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore), and probed with antibodies against Bim (Stressgen), Bax (Upstate), Bak (Upstate), and β-actin (Sigma).

Quantitative PCR

CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), TCR-βhiCD4+ single positive (SP), and TCR-βhiCD8+ SP thymocytes were isolated by FACS sorting, and used for RNA extraction. TGF-βRII mRNA amounts were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the primer set: 5′-atctggaaaacgtggagtcg-3′ and 5′-tccttcacttctcccacagc-3′. To determine the expression of common γ chain cytokines, thymus was lyzed by Trizol for RNA preparation. The amount of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 was measured by qPCR with the following primer sets: 5′-cccacttcaagctccacttc-3′ and 5′-ttcaattctgtggcctgctt-3′ (IL-2), 5′-atccttgttctgctgcctgt-3′ and 5′-tggttcattattcgggcaat-3′ (IL-7), 5′-cattttgggctgtgtcagtg-3′ and 5′-gcaattccaggagaaagcag-3′ (IL-15). The expression of TGF-βRII, IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 was normalized to the β-actin amounts detected by qPCR with the primer set: 5′-ttgctgacaggatgcagaag-3′ and 5′-acatctgctggaaggtggac-3′.

Apoptosis Assays

Foxp3+ Tregs, conventional T cells, and OT-II T cells were purified by FACS sorting, and cultured in T cell medium (RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 0.1 mM glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin and nonessential amino acids) for 6 and 12 hr. Cell apoptosis was determined by staining with FITC-labeled annexin V (BD Biosciences). To assess anti-CD3-induced thymocyte apoptosis in vitro, total thymocytes were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hr, and stained with fluorescent-dye-labeled anti-TCR-β, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and annexin V. The annexin V+ apoptotic cells in thymic subpopulations were determined by Flow cytometry.

For active caspase measurements, thymocytes were cultured in T cell medium in the presence of 10 μM FITC-VAD-FMK (Promega) for 20 min, washed twice with cold PBS, and stained with antibodies against cell surface markers before subject to Flow cytometric analysis.

The TUNEL protocol with Tyramide Signal Amplification was developed at the Molecular Cytology Core Facility at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Four-micron tissue sections were treated with 20 μg/ml Proteinase K (Sigma) for 15 min at 37°C, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Blocking of endogenous peroxidases was performed for 10 min in 1% H2O2 at room temperature. TdT (terminyl deoxynucleodityl transferase, Roche)-mediated biotin-dUTP end nick labeling reaction was performed at 4°C overnight. Tyramide-biotin (Perkin Elmer) was used to amplify the signal. Biotin was detected using a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories). Peroxidase activity was determined by incubating the slides in 0.2 mg/ml DAB in PBS with 50 μl of 30% H2O2 for 5 min at room temperature. Slides were counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific), dehydrated and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific). TUNEL-positive areas from 4 sections were quantified with the MetaMorph software.

Treg Cell Suppression Assay

Splenic and lymph node CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) were isolated from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− by FACS sorting. CD44loCD4+RFP− cells sorted from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+ mice were labeled with 4 μM of Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Sigma) at 37°C for 10 min, and used as responder T cells (Tresp). 5×104 Tresp cells were cultured in 96-well plates with 105 irradiated splenocytes and 2 μg/ml CD3 antibody in the presence of different numbers of Tregs for 72 hr.

Histopathology

Tissues from sacrificed animals were fixed in Safefix II (Protocol) and embedded in paraffin. 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance for difference in a particular measurement between groups. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1 Enhanced Anti-CD3-induced Apoptosis of TGF-βRII-deficient T Cells. (A) Iso-type control of anti-TGF-βRII staining of thymic subpopulations. (B, C) Thymocytes isolated from 12-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice were treated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hr. Apoptosis of CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), CD4+CD8− single positive (CD4+SP) and CD4−CD8+ (CD8+SP) thymocytes was determined by annexin V staining (B). Percentages of annexin V+ apoptotic cells from eight groups of mice are presented (C). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

Figure 2 T cell Negative Selection and nTreg Development in TGF-βRII-deficient OT-II RIP-mOVA Mice in the Presence or Absence of Bim. (A) TCR-β expression in thymic OT-II T cells (top panel), and CD69 and CD62L expression in thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells (bottom panel) from 8-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. (B) Foxp3 expression in TCR-βhi OT-II T cells from 8-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. (C–D) Correction of T cell negative selection in the absence of Bim. Flow cytometric analysis of TCR-β expression in thymic OT-II T cells (A) and CD69 and CD62L expression in thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells (B) from 5-week-old Bcl2l11−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

Figure 3 TGF-β Control of Thymic nTreg Survival and Proliferation. (A) Thymic nTregs were purified by FACS sorting from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice, and cultured for 6 hr. T cell viability before and after the cell culture was determined by annexin V staining. A representative of two independent experiments is shown. (B–D) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression (B) in thymic TCR-βhi CD4+ T cells, and caspase activation (C) and Ki67 expression (D) in thymic nTregs from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice.

Figure 4 Reduced CD127 Expression Does not Cause the nTreg Defects in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell size and the expression of Foxp3, CD69, CD62L, CTLA4, GITR, ICOS, CD27, CD25, CD122, CD132, and CD127 in nTregs from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. The change of expression was calculated by dividing the mean intensity of fluorescence (MIF) of Tgfbr2−/− Tregs by that of Tgfbr2+/+ Tregs, and is shown at the corner of each sub-figure. These are representative results of four pairs of mice. (B) Thymic expression of common γ chain cytokines in 4–5-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. The mRNA amounts of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 were determined by quantitative PCR, and were normalized to the amounts of β-actin. (C, D) Flow cytometric analysis of CD127 expression in thymic nTregs (C), and Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells (D) from 4-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice in the absence or presence of Il7r transgene (Il7rTg). A representative of two independent experiments is shown.

Figure 5 Effects of Bim Ablation on Thymic and Peripheral Tregs in Tgfbr2−/− or CD28−/− Mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (B) Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells and splenic CD4+ T cells from 6-week-old CD28+/+Bcl2l11+/+, CD28−/−Bcl2l11+/+, CD28+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and CD28−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression in splenic CD4+ T cells from 4-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (D) Tregs purified from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice were labeled with CFSE, and co-cultured with irradiated T cell-depleted splenocytes in the presence of 2 μg/ml CD3 antibody for 72 h. Cell division was assessed by CFSE dilution.

Figure 6 Bim deficiency Does not Rescue the Multi-focal Inflammatory Disorder in Tgfbr2−/− Mice. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of stomach, lung, liver, pancreas, and salivary gland sections from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/− Bcl2l11−/− mice at 18-day-old (Original magnification, 20×). A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Flavell, W. Heath, and A. Singer for providing critical mouse strains, A. Rudensky, E. Pamer, D. Sant’Angelo, M. Huse, Y. Zheng, and R. Jacobson for discussions. The projects described were supported by KO1 AR053595 from NIAMS (M.O.L.) and an Arthritis Foundation Investigator Award (M.O.L.). M.O.L. is a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar.

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Benoist C, Mathis D. The cellular mechanism of Aire control of T cell tolerance. Immunity. 2005;23:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolou I, Sarukhan A, Klein L, von Boehmer H. Origin of regulatory T cells with known specificity for antigen. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:756–763. doi: 10.1038/ni816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista JL, Lio CW, Lathrop SK, Forbush K, Liang Y, Luo J, Rudensky AY, Hsieh CS. Intraclonal competition limits the fate determination of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:610–617. doi: 10.1038/ni.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet P, Purton JF, Godfrey DI, Zhang LC, Coultas L, Puthalakath H, Pellegrini M, Cory S, Adams JM, Strasser A. BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is required for apoptosis of autoreactive thymocytes. Nature. 2002;415:922–926. doi: 10.1038/415922a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouneaud C, Kourilsky P, Bousso P. Impact of negative selection on the T cell repertoire reactive to a self-peptide: a large fraction of T cell clones escapes clonal deletion. Immunity. 2000;13:829–840. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Kanagawa O, Sleckman BP, Muglia LJ. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by T cell activation is mediated by glucocorticoids in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;169:1837–1843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jin W, Tian H, Sicurello P, Frank M, Orenstein JM, Wahl SM. Requirement for transforming growth factor beta1 in controlling T cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:439–453. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Benoist C, Mathis D. How defects in central tolerance impinge on a deficiency in regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14735–14740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danke NA, Koelle DM, Yee C, Beheray S, Kwok WW. Autoreactive T cells in healthy individuals. J Immunol. 2004;172:5967–5972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPaolo RJ, Shevach EM. CD4+ T-cell development in a mouse expressing a transgenic TCR derived from a Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:234–240. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlen L, Read S, Gorelik L, Hurst SD, Coffman RL, Flavell RA, Powrie F. T cells that cannot respond to TGF-beta escape control by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:737–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerer M, Hill JA, Mathis D, Benoist C. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: differentiation, specification, subphenotypes. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:689–695. doi: 10.1038/ni.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3− expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1039–1049. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Baldwin TA, Jameson SC. Central tolerance: learning self-control in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:772–782. doi: 10.1038/nri1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:401–410. doi: 10.1038/ni1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, Petrone AL, Holenbeck AE, Lerman MA, Naji A, Caton AJ. Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:301–306. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz SZ, Rudensky A. Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity. 2009;30:616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahata K, Misaki Y, Yamauchi M, Tsunekawa S, Setoguchi K, Miyazaki J, Yamamoto K. Generation of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells from autoreactive T cells simultaneously with their negative selection in the thymus and from nonautoreactive T cells by endogenous TCR expression. J Immunol. 2002;168:4399–4405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurts C, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Allison J, Miller JF, Kosaka H. Constitutive class I-restricted exogenous presentation of self antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:923–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani SA, Masud A, Kuida K, Porter GA, Jr, Booth CJ, Mehal WZ, Inayat I, Flavell RA. Caspases 3 and 7: key mediators of mitochondrial events of apoptosis. Science. 2006;311:847–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1115035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung MW, Shen S, Lafaille JJ. TCR-dependent differentiation of thymic Foxp3+ cells is limited to small clonal sizes. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2121–2130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Flavell RA. TGF-beta: a master of all T cell trades. Cell. 2008;134:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Sanjabi S, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity. 2006;25:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Wan YY, Flavell RA. T cell-produced transforming growth factor-beta1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1- and Th17-cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;26:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang P, Li J, Kulkarni AB, Perruche S, Chen W. A critical function for TGF-beta signaling in the development of natural CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:632–640. doi: 10.1038/ni.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwinski MW, Sun J, Hilliard B, Gong S, Xue F, Carmody RJ, DeVirgiliis J, Chen YH. Critical roles of Bim in T cell activation and T cell-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1706–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI37619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek TR, Yu A, Vincek V, Scibelli P, Kong L. CD4 regulatory T cells prevent lethal autoimmunity in IL-2Rbeta-deficient mice. Implications for the nonredundant function of IL-2. Immunity. 2002;17:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis D, Benoist C. Back to central tolerance. Immunity. 2004;20:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer E. Negative selection--clearing out the bad apples from the T-cell repertoire. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:383–391. doi: 10.1038/nri1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Yu Q, Erman B, Appelbaum JS, Montoya-Durango D, Grimes HL, Singer A. Suppression of IL7Ralpha transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines: a novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmell JC, Lindsten T, Zong WX, Cinalli RM, Thompson CB. Deficiency in Bak and Bax perturbs thymic selection and lymphoid homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:932–939. doi: 10.1038/ni834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, Ashourian N, Singh B, Sharpe A, Bluestone JA. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-beta and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Williams GT, Kingston R, Jenkinson EJ, Owen JJ. Antibodies to CD3/T-cell receptor complex induce death by apoptosis in immature T cells in thymic cultures. Nature. 1989;337:181–184. doi: 10.1038/337181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai X, Cowan M, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. CD28 costimulation of developing thymocytes induces Foxp3 expression and regulatory T cell differentiation independently of interleukin 2. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:152–162. doi: 10.1038/ni1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco R, Alcalde V, Yang Y, Sauer K, Zuniga EI. Cell-intrinsic transforming growth factor-beta signaling mediates virus-specific CD8+ T cell deletion and viral persistence in vivo. Immunity. 2009;31:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tone Y, Furuuchi K, Kojima Y, Tykocinski ML, Greene MI, Tone M. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:194–202. doi: 10.1038/ni1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Santen HM, Benoist C, Mathis D. Number of T reg cells that differentiate does not increase upon encounter of agonist ligand on thymic epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1221–1230. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang KB, Yang J, Mahmud SA, Burchill MA, Vegoe AL, Farrar MA. IL-2, -7, and -15, but not thymic stromal lymphopoeitin, redundantly govern CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2008;181:3285–3290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LS, Chodos A, Eggena M, Dooms H, Abbas AK. Antigen-dependent proliferation of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;198:249–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan YY, Flavell RA. Identifying Foxp3− expressing suppressor T cells with a bicistronic reporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5126–5131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SG, Wang JH, Gray JD, Soucier H, Horwitz DA. Natural and induced CD4+CD25+ cells educate CD4+CD25− cells to develop suppressive activity: the role of IL-2, TGF-beta, and IL-10. J Immunol. 2004;172:5213–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1 Enhanced Anti-CD3-induced Apoptosis of TGF-βRII-deficient T Cells. (A) Iso-type control of anti-TGF-βRII staining of thymic subpopulations. (B, C) Thymocytes isolated from 12-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice were treated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hr. Apoptosis of CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), CD4+CD8− single positive (CD4+SP) and CD4−CD8+ (CD8+SP) thymocytes was determined by annexin V staining (B). Percentages of annexin V+ apoptotic cells from eight groups of mice are presented (C). The p values between the groups are shown. *depicts significant difference.

Figure 2 T cell Negative Selection and nTreg Development in TGF-βRII-deficient OT-II RIP-mOVA Mice in the Presence or Absence of Bim. (A) TCR-β expression in thymic OT-II T cells (top panel), and CD69 and CD62L expression in thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells (bottom panel) from 8-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. (B) Foxp3 expression in TCR-βhi OT-II T cells from 8-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. (C–D) Correction of T cell negative selection in the absence of Bim. Flow cytometric analysis of TCR-β expression in thymic OT-II T cells (A) and CD69 and CD62L expression in thymic TCR-βhi OT-II T cells (B) from 5-week-old Bcl2l11−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− OT-II mice in the absence or presence of RIP-mOva transgene. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

Figure 3 TGF-β Control of Thymic nTreg Survival and Proliferation. (A) Thymic nTregs were purified by FACS sorting from Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice, and cultured for 6 hr. T cell viability before and after the cell culture was determined by annexin V staining. A representative of two independent experiments is shown. (B–D) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression (B) in thymic TCR-βhi CD4+ T cells, and caspase activation (C) and Ki67 expression (D) in thymic nTregs from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice.

Figure 4 Reduced CD127 Expression Does not Cause the nTreg Defects in TGF-βRII-deficient Mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell size and the expression of Foxp3, CD69, CD62L, CTLA4, GITR, ICOS, CD27, CD25, CD122, CD132, and CD127 in nTregs from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. The change of expression was calculated by dividing the mean intensity of fluorescence (MIF) of Tgfbr2−/− Tregs by that of Tgfbr2+/+ Tregs, and is shown at the corner of each sub-figure. These are representative results of four pairs of mice. (B) Thymic expression of common γ chain cytokines in 4–5-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice. The mRNA amounts of IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 were determined by quantitative PCR, and were normalized to the amounts of β-actin. (C, D) Flow cytometric analysis of CD127 expression in thymic nTregs (C), and Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells (D) from 4-day-old Tgfbr2+/+ and Tgfbr2−/− mice in the absence or presence of Il7r transgene (Il7rTg). A representative of two independent experiments is shown.

Figure 5 Effects of Bim Ablation on Thymic and Peripheral Tregs in Tgfbr2−/− or CD28−/− Mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells from 16-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (B) Foxp3 expression in thymic TCR-βhiCD4+ T cells and splenic CD4+ T cells from 6-week-old CD28+/+Bcl2l11+/+, CD28−/−Bcl2l11+/+, CD28+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and CD28−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression in splenic CD4+ T cells from 4-day-old Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/− and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice. (D) Tregs purified from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11−/− mice were labeled with CFSE, and co-cultured with irradiated T cell-depleted splenocytes in the presence of 2 μg/ml CD3 antibody for 72 h. Cell division was assessed by CFSE dilution.

Figure 6 Bim deficiency Does not Rescue the Multi-focal Inflammatory Disorder in Tgfbr2−/− Mice. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of stomach, lung, liver, pancreas, and salivary gland sections from Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2−/−Bcl2l11+/+, Tgfbr2+/+Bcl2l11−/−, and Tgfbr2−/− Bcl2l11−/− mice at 18-day-old (Original magnification, 20×). A representative of three independent experiments is shown.