Abstract

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common disorders with an increasing incidence and prevalence. Alcohol consumption may be a risk factor for GERD; however, the relationship remains to be fully elucidated. The results of different studies are diverse and contradictory. Systematic investigations concerning this matter are inappropriate and further well-designed prospective studies are needed to clarify the effect of alcohol on GERD.

Keywords: Alcohol, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Motility, Acid

1. Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, commonly referred to as GERD, is one of the most common disorders, and its incidence and prevalence have increased over the last two decades. GERD is characterized by the sensation of substernal burning caused by abnormal reflux of gastric contents backward up into the esophagus. GERD has two different manifestations, reflux esophagitis (RE) and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), depending on the presence or absence of esophageal mucosal breaks. Symptoms of GERD are chronic and can significantly impair quality of life. Therefore, it has been regarded as a considerable health problem in most of the world. Recommendations for lifestyle modifications are based on the presumption that alcohol, tobacco, certain foods, body position, and obesity contribute to the dysfunction in the body’s defense system of antireflux.

Alcohol is one of the most commonly abused drugs and one of the leading preventable causes of death worldwide (Lopez et al., 2006). Heavy drinking puts people at a high risk for many adverse health events, potentially including GERD. Alcohol consumption may increase symptoms of GERD and cause damage to the esophageal mucosa. In many cases, symptoms of GERD can be controlled after withdrawl of alcoholic beverages. So patients with symptomatic GERD are frequently recommended to avoid alcohol consumption or to consume moderate amount of alcohol. However, evidence on the association between GERD and alcohol consumption has been conflicting.

2. Association between alcohol and GERD

Many studies have been performed to examine the association between the alcohol consumption and the risk of GERD. A cross-sectional survey was performed in 87 patients with esophagitis diagnosed by endoscopy. Twenty-three patients were asymptomatic and 64 were symptomatic. The alcohol consumption was (294.2±73.4) g/week in the symptomatic group and (53.2±13.4) g/week in the asymptomatic group (Nozu and Komiyama, 2008). Chronic excessive alcohol abuse has also been shown to be associated with GERD (odds ratio (OR)=2.85, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.67–4.49) (Wang et al., 2004).

The association between alcohol and different types of GERD has also been studied. Hung et al. (2005) concluded that erosive esophagitis was directly related to alcohol consumption (Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.091, P=0.01). Alcohol consumption has also been shown to be more common in persons suffering from erosive esophagitis compared to individuals with NERD based on a multivariate analysis (OR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.0–8.3) (Lee et al., 2009).

Total alcohol consumption has been shown to be significantly associated with GERD. Japanese researchers have studied the correlation between different magnitudes of alcohol consumption and RE. Compared to people who never drank, heavy drinkers (who drink more than 50 g ethanol per day), moderate drinkers (who drink 25 to 50 g ethanol per day), and light drinkers (who drink less than 25 g ethanol per day) had ORs for erosive esophagitis of 1.988 (95% CI: 1.120–3.534, P=0.0190), 1.880 (95% CI: 1.015–3.484, P=0.0445), and 1.110 (95% CI: 0.553–2.228, P=0.7688), respectively (Akiyama et al., 2008).

There are generally three types of alcoholic beverages: beers, wines, and liquors. Different types of alcoholic beverages may have differential effects on the risk for GERD. Anderson et al. (2009) investigated the association between different types of alcohol and RE in individuals who were 21 years old. Compared to controls, RE patients were twice as likely to report drinking at least one alcoholic drink per month. There were no significant associations between wine or liquor consumption and RE (Mohammed et al., 2005; Nocon et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2009). Interestingly, the highest intake of beer (≥11.928 L per week) was inversely associated with RE (Anderson et al., 2009). The same inverse trend was observed in Italy where non-heavy drinkers had a higher prevalence of GERD than heavy drinkers: 56% vs. 49% (OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–1.0, P=0.0001) (Dore et al., 2008). This suggests that alcohol may have some beneficial effects on GERD. In a separate study, 15 patients with RE and 10 with NERD drank 500 ml beer, 300 ml white wine, or identical amounts of water (controls) along with a standardized meal in a randomized order. Both beer and wine increased the presence of reflux compared to water. There was no difference in reflux induction found between beer and wine (Pehl et al., 1993; 2006).

Most researchers have concluded that drinking alcohol, especially large quantities, increases the risk of GERD. Despite this, a Swedish study found the opposite. Nilsson et al. (2004) determined that alcohol consumption was not associated with any change in the risk of GERD. In addition, the cessation of alcohol consumption was not shown to improve esophageal pH profiles or reduce symptoms (Kaltenbach et al., 2006).

3. Effect of alcohol on GERD

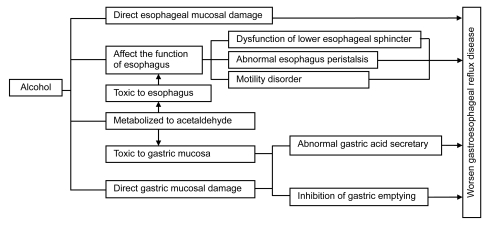

GERD results from the excessive reflux of gastric contents backward up into the esophagus. Under normal conditions, reflux is prevented by the function of the antireflux barrier at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) and the delicate interplay of a host of anatomic and physiologic factors, including the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) that prevents the backflow of gastric contents. Generally, the LES yields with pressure and relaxes after each swallow to allow food to pass into the stomach. Reflux occurs when LES does not sufficiently contract or the pressure in the stomach exceeds the pressure created by the LES. Factors that may contribute to the mechanism of GERD include defection of the LES, damage of esophageal peristalsis, delayed gastric emptying, and gastric acid production as well as bile reflux. Possible factors affecting the development of GERD in alcoholics are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Possible factors affecting the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in alcoholics

As one of the risks for GERD, the effect of alcohol on the esophagus and stomach differs from its effect on other organs such as the pancreas or liver. Alcoholic beverages directly contact the esophageal and gastric mucosae and may cause direct mucosal damage (Franke et al., 2005). Esophageal motor abnormalities including peristaltic dysfunction are frequent in alcoholism in both humans and cats (Keshavarzian et al., 1990a; Grande et al., 1996).

3.1. Motility

Chronic and long-term consumption of alcohol in excessive quantities will damage many systems and organs in the body. Excessive alcohol consumption has been associated with the development of GERD through abnormalities of the pressure of LES and esophageal motility (Kaufman and Kaye, 1978). Ferdinandis et al. (2006) studied the association between esophageal motor activity and chronic alcoholism. Twenty four-hour pH-metry and ambulatory esophageal manometry were performed with a combined pH and pressure catheter in alcoholic subjects and controls. Results of the study show that hypertension of the LES was observed in alcoholic subjects with alcoholic autonomic neuropathy. The effects on the LES may partially be caused by a disturbance in the function of the autonomous nervous system. Esophageal body motility parameters were not significantly different between alcoholic subjects and controls (Keshavarzian et al., 1990b; Ferdinandis et al., 2006). Silver et al. (1986) found an increase in LES pressure which reverted to normal after withdrawal from ethanol. It has been shown that the amplitude and duration of HCl- and NaCl-induced esophageal peristaltic contractions in alcoholics were significantly higher than those in controls (Keshavarzian et al., 1992).

Gastroesophageal reflux frequently occurs in association with acute alcohol ingestion. Endo et al. (2005) reported a case of acute esophageal necrosis caused by alcohol abuse. The patient consumed 1.8 L of shochu, distilled spirits containing 25% alcohol, on the previous day. The effect of acute alcohol consumption on the LES is contrary to that of chronic ethanol administration, as acute alcohol consumption may relax the LES, allowing the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. Fields et al. (1995) have found that alcohol can directly inhibit contractility of the esophagus of a cat in vitro. Keshavarzian et al. (1994) also studied the effect of intravenous administration of ethanol on the LES in a cat model and found that the LES pressure and amplitude of lower (smooth muscle portion) esophageal peristaltic contractions decreased. The ethanol also prolonged the duration of lower esophageal peristaltic contractions. Further, they have found that alcohol inhibition of Ca2+ influx into esophageal muscle in vitro is selective for smooth muscle, which can explain why alcohol decreases contractility of smooth muscle of the LES and lower esophagus (LE), but not the striated muscle of the upper esophagus (Keshavarzian et al., 1991). This process could be the underlying mechanism for alcohol inhibition of contractility of esophageal smooth muscle. These results are similar to the study that determined that ethanol (1%–10%) decreased the tissue resistance of squamous epithelium in the rabbit esophagus in a dose-dependent manner (Bor and Capanoglu, 2009).

The effect of ethanol on nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux was studied by Vitale et al. (1987), in 17 healthy volunteers with or without 120 ml of Scotch whisky after the evening meal. The distal esophagus was exposed to significant amounts of acid. The normal acid clearance of the esophagus in the supine position was impaired after only moderate amounts of alcohol ingestion.

Different serum concentrations of alcohol have different effects on the body. The amplitudes of esophageal peristaltic waves were reduced in the distal and proximal segments when the serum alcohol concentration was 117 mg/dl in normal volunteers. However, esophageal and LES functions were not affected at serum alcohol concentrations less than 70 mg/dl (Mayer et al., 1978).

3.2. Gastric acid secretion

One of the most usual causes of acid reflux is the large increase in the production of gastric acid. Acid, which is the primary cause of heartburn and regurgitation, may be the principal factor in determining the severity of esophagitis (Richter, 2009). The relationship between ethanol and gastric acid secretion has been investigated by many researchers; however, the results of these investigations are contradictory. Generally, intravenous ethanol administration causes a dose-dependent stimulation of gastric acid output. Low concentrations of ethanol (<5%, v/v) are moderate stimulants, whereas higher concentrations (5% to 40%, v/v) have no stimulatory effect and actually show an inhibitory effect (Singer and Leffmann, 1988). Pure ethanol administered by any way does not cause gastrin release in humans. Oral and intragastric administrations of ethanol do not increase gastrin release, whereas beer and red and white wines are potent stimulants of gastrin release and gastric acid secretion in humans (Singer and Leffmann, 1988). The effect of chronic alcohol abuse on gastric acid secretion still needs to be elucidated. Chronic alcoholics may have an enhanced, diminished, or normal acid secretory capacity (Singer et al., 1987; Chari et al., 1993).

3.3. Alcohol metabolism

It is known that alcohol-related problems are affected by individual variations in the way that alcohol is broken down and eliminated by the body. Alcohol is generally metabolized via several pathways. The breakdown by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is the most common pathway (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007). First, alcohol is metabolized by ADH to a highly toxic substance called acetaldehyde. Second, acetaldehyde is further metabolized to acetate, which is then metabolized into carbon dioxide and water for easy elimination. The enzymes cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and catalase can also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007).

Differences in alcohol metabolism may put some people at greater risk for alcohol problems (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007). Yin et al. (1993) compared the isoenzymes of ADH and ALDH from surgically-excised esophageal and gastric mucosae. The activity of esophageal ADH was elevated by approximately 4-fold and the activity of ALDH accounted for 20% of the stomach enzymes, suggesting that an accumulation of intracellular acetaldehyde exists during ethanol ingestion. This toxic and reactive metabolite may be involved in the mechanism of ethanol-associated esophageal disorders.

4. Conclusions

The relationship between alcohol consumption and the development of GERD remains to be fully elucidated. Although many studies have focused on this relationship, there are diverse and contradictory results. Furthermore, alcohol possibly has different effects on NERD and erosive esophagitis. Some of the contradictory results can be explained by variations in experimental conditions and animal models used in each study. Alcohol consumption probably precipitates GERD. Exposure of the esophagus and stomach to alcohol may cause direct damage to esophageal and gastric mucosae. In addition, toxic acetaldehyde metalized from alcohol could affect the function of the esophagus and stomach. Furthermore, dysfunction of the LES and esophageal peristalsis and abnormal gastric acid secretion may be involved in the pathogenesis of alcohol-related GERD. Systemic investigations concerning this matter are still inadequate and further well-designed prospective studies are needed to clarify the effect of alcohol on GERD.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Key Technology R & D Program of China (No. 2008BAI52B03) and the Medicine & Health Program of Zhejiang Province (No. 2006B037), China

References

- 1.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Iida H, Mawatari H, Endo H, Hosono K, Yoneda K, Fujiata K, Yoneda M, Takahashi H, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s epithelium in Japanese men. BMC Gastroenterology. 2008;8(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson LA, Cantwell MM, Watson RG, Johnson BT, Murphy SJ, Ferquson HR, McGuiqan J, Comber H, Reynolds J, Murray L. The association between alcohol and reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):799–805. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bor S, Capanoglu D. The additive effect of ethanol and extract of cigarette smoke on rabbit esophagus epithelium. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;24(2):316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chari S, Teyssen S, Singer MV. Alcohol and gastric acid secretion in humans. Gut. 1993;34(6):843–847. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.6.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dore MP, Maragkoudakis E, Fraley K, Pedroni A, Tadeu V, Realdi G, Graham DY, Malaty HM. Diet, lifestyle and gender in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(8):2027–2032. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endo T, Sakamoto J, Sato K, Takimoto M, Shimaya K, Mikami T, Munakata A, Shimoyama T, Fukuda S. Acute esophageal necrosis caused by alcohol abuse. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11(35):5568–5570. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i35.5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferdinandis TG, Dissanayake AS, de Silva HJ. Chronic alcoholism and esophageal motor activity: a 24-h ambulatory manometry study. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;21(7):1157–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields JZ, Jacyno M, Wasyliw R, Winship D, Keshavarzian A. Ethanol inhibits contractility of esophageal smooth muscle strips. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19(6):1403–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke A, Teyssen S, Singer MV. Alcohol-related diseases of the esophagus and stomach. Digestive Diseases. 2005;23(3-4):204–213. doi: 10.1159/000090167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grande L, Monforte R, Ros E, Toledo-Pimentel V, Estruch R, Lacima G, Urbano-Marquez A, Pera C. High amplitude contractions in the middle third of the oesophagus: a manometric marker of chronic alcoholism? Gut. 1996;38(5):655–662. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung CS, Lee CL, Yang JN, Liao PT, Tu TC, Chen TK, Wu CH. Clinical application of Carlsson’s questionnaire to predict erosive GERD among healthy Chinese. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;20(12):1900–1905. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(9):965–971. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman SE, Kaye MD. Induction of gastro-oesophageal reflux by alcohol. Gut. 1978;19(4):336–338. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshavarzian A, Rizk G, Urban G, Willson C. Ethanol-induced esophageal motor disorder: development of an animal model. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1990;14(1):76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keshavarzian A, Polepalle C, Iber FL, Durkin M. Esophageal motor disorder in alcoholics: result of alcoholism or withdrawal? Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1990;14(4):561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keshavarzian A, Urban G, Sedghi S, Willson C, Sabella L, Sweeny C, Anderson K. Effect of acute ethanol on esophageal motility in cat. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15(1):116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keshavarzian A, Polepalle C, Iber FL, Durkin M. Secondary esophageal contractions are abnormal in chronic alcoholics. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1992;37(4):517–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01307573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshavarzian A, Zorub O, Sayeed M, Urban G, Sweeney C, Winship D, Fields J. Acute ethanol inhibits calcium influxes into esophageal smooth but not striated muscle: a possible mechanism for ethanol-induced inhibition of esophageal contractility. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;270(3):1057–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee ES, Kim N, Lee SH, Park YS, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Lee DH, Jung HC, Song IS. Comparison of risk factors and clinical responses to proton pump inhibitors in patients with erosive oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;30(2):154–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer EM, Grabowski CJ, Fisher RS. Effects of graded doses of alcohol upon esophageal motor function. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(6):1133–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammed I, Nightingale P, Trudgill NJ. Risk factors for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a community study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2005;21(7):821–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Vol. 72. USA: NIAAA Publications Distribution Center; 2007. Alcohol Alert: Alcohol Metabolism: An Update; pp. 1–6. (Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa72/aa72.htm) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53(12):1730–1735. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nocon M, Labenz J, Willich SN. Lifestyle factors and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux—a population-based study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;23(1):169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nozu T, Komiyama H. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic esophagitis. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43(1):27–31. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pehl C, Wendl B, Pfeiffer A, Schmidt T, Kaess H. Low-proof alcoholic beverages and gastroesophageal reflux. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1993;38(1):93–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01296779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pehl C, Wendl B, Pfeiffer A. White wine and beer induce gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with reflux disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;23(11):1581–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter JE. Role of the gastric refluxate in gastroesophageal reflux disease: acid, weak acid and bile. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2009;338(2):89–95. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181ad584a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver LS, Worner TM, Korsten MA. Esophageal function in chronic alcoholics. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1986;81(6):423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer MV, Leffmann C. Alcohol and gastric acid secretion in humans: a short review. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1988;23(s146):11–21. doi: 10.3109/00365528809099126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer MV, Leffmann C, Eysselein VE, Calden H, Goebell H. Action of ethanol and some alcoholic beverages on gastric acid secretion and release of gastrin in humans. Gastroenterology. 1987;93(6):1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitale GC, Cheadle WG, Patel B, Sadek SA, Michel ME, Cuschieri A. The effect of alcohol on nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. JAMA The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1987;258(15):2077–2079. doi: 10.1001/jama.258.15.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JH, Luo JY, Dong L, Gong J, Tong M. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a general population-based study in Xi’an of Northwest China. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10(11):1647–1651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin SJ, Chou FJ, Chao SF, Tsai SF, Liao CS, Wang SL, Wu CW, Lee SC. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases in human esophagus: comparison with the stomach enzyme activities. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17(2):376–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]