Abstract

Design of non-nucleoside inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is being pursued with the assistance of free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations to predict relative free energies of binding. Extension of azole-containing inhibitors into an ‘eastern’ channel between Phe227 and Pro236 has led to the discovery of potent and structurally novel derivatives.

Non-nucleoside inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (NNRTIs) are an important component of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of HIV infection.1 NNRTIs disrupt the activity of HIV-RT via binding to an allosteric pocket in the vicinity of the polymerase active site.2-4 However, the therapeutic effectiveness of NNRTIs is challenged by rapid emergence of drug-resistant, variant strains of the virus.5 Mutations such as V106A, Y181C, and K103N occur in the NNRTI binding pocket. While the search for an effective vaccine continues, the need for new antiretroviral drugs with improved pharmacological properties and resistance profiles is apparent.

Recent reports have described the discovery and free energy perturbation (FEP)-guided optimization of an U-5Het-NH-Ar scaffold, where U is an unsaturated hydrophobic group, and 5Het is an azole.6,7 Though potent NNRTIs were identified with EC50 values as low as 10-20 nM, search for novel NNRTIs that provide activity against a broader spectrum of variants continues. In particular, we have sought to reduce the dependence of the NNRTI binding on the interaction between the U group and Tyr181 by extending the Ar group into the distal region of the binding site, which is lined by Val106, Glu224, Pro225, Pro226, Phe227 and Pro236. The present report summarizes FEP-guided results for these ‘eastern extensions’ in the oxazole and oxadiazole series.

The syntheses of oxadiazole 1 and oxazole 3 derivatives were performed as shown in Schemes 1 and 2.6 The isothiocyanates 2 required for the synthesis of oxazole derivatives 3 were prepared from substituted benzyl alcohols, phenols, or halonitrobenzenes.8,9 As illustrated for 1e, extended oxadiazole derivatives were synthesized by Cu-catalyzed coupling of 2-amino-oxadiazole 4 with aryl iodides, e.g., 5.10,11 4 was synthesized from 2-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)acetohydrazide and cyanogen bromide.12,13 Coupling partner 5 was prepared by alkylation of 4-iodo-benzyl alcohol with the requisite bromomethyl-pyridine.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

Activities against the IIIB and variant strains of HIV-1 were measured using MT-2 human T-cells; EC50 values are obtained as the dose required to achieve 50% protection of the infected cells by the MTT colorimetric method. CC50 values for inhibition of MT-2 cell growth by 50% are obtained simultaneously.6,14,15

Monte Carlo/FEP (MC/FEP) calculations were executed to compute relative free energies of binding using standard protocols.16 Coordinates of HIV-RT complexes were constructed from the 1s9e PDB file17 using the BOMB program.7 Desired analogs were grown from ammonia, which was positioned to hydrogen-bond with the C=O of Lys101 in the NNRTI binding site.6,17 The model included the 178 amino acid residues nearest the ligand. Short conjugate-gradient minimizations were carried out on the initial structures for all complexes to relieve any unfavorable contacts. Coordinates for the free ligands were obtained by extraction from the complexes.

The MC/FEP calculations were performed with MCPRO.18 The unbound ligands and complexes were solvated in 25-Å caps with 2000 and 1250 TIP4P water molecules. The FEP calculations utilized 11 windows of simple overlap sampling.19 Each window covered 10-15 million (M) configurations of equilibration and 20-30 M configurations of averaging. The ligand and side chains within ca. 10 Å of the ligand were fully flexible, while the protein backbone was kept fixed during the MC runs. The energetics were evaluated with the OPLS-AA force field for the protein,20,21 OPLS/CM1A21 for the ligands, and TIP4P for water.22

Model building with BOMB indicated that extension from the para position of the anilinyl ring with a linker-Het motif was feasible. In view of our report of 1a,6b a MOM linker was considered first. An FEP pyridine scan7 provided the results in Table 1. The 2- and 6-pyridinyl and 3- and 5-pyridinyl structures for the complexes do not interconvert during the MC simulations, so they are separately considered. The FEP results predicted little difference in activity for the pyridinyl isomers. The oxadiazole derivatives were then synthesized and assayed (Table 2). Indeed, though 1c - 1e are active, the EC50 values are similar with little change from 1a. Furanyl and thienyl analogs did not fare better. Based on prior experience,6,7 the differences in Table 1 are too small to lead to any clear preference in the cell-based assay. The inactivity of the phenyl analogue 1b reflects poorer electrostatic interaction with the proximal protonated His235.

Table 1.

Relative Free Energies of Binding from MC/FEP Calculations.

| |

|---|---|

| R′ | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

| CH2OCH2-Phenyl | 0.0 |

| CH2OCH2-2-Pyridinyl | −0.25 ± 0.28 |

| CH2OCH2-3-Pyridinyl | −0.89 ± 0.20 |

| CH2OCH2-4-Pyridinyl | −0.36 ± 0.27 |

| CH2OCH2-5-Pyridinyl | 0.51 ± 0.22 |

| CH2OCH2-6-Pyridinyl | 0.24 ± 0.22 |

Table 2.

Anti-HIV-1 Activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50), μM.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R′ | EC50a | CC50 |

| 1a | CH2OCH3 | 4.3 | 100 |

| 1b | CH2OCH2-Phenyl | NA | 84 |

| 1c | CH2OCH2-2-Pyridinyl | 5.0 | >100 |

| 1d | CH2OCH2-3-Pyridinyl | 4.6 | 81 |

| 1e | CH2OCH2-4-Pyridinyl | 1.6 | 81 |

| 1f | CH2OCH2-2-Furanyl | 2.8 | 12.0 |

| 1g | CH2OCH2-3-Furanyl | NA | 21.0 |

| 1h | CH2OCH2-3-Thienyl | NA | >100 |

NA indicates that EC50 > CC50.

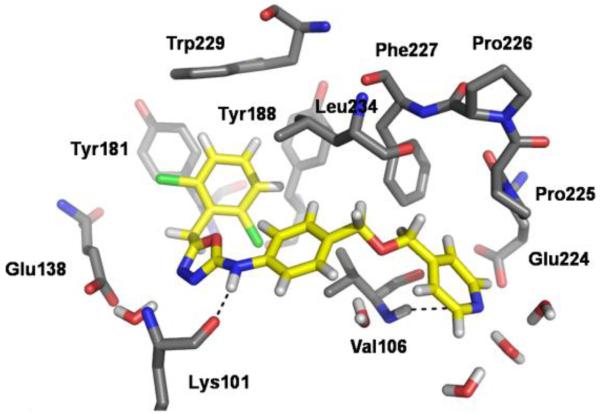

A computed structure for the 4-pyridinyl analog is shown in Figure 1. The benzyl and anilinyl rings of 1e form π-π interactions with Tyr181, Tyr188, Trp229, and Tyr318 (not shown), and there is an NH-O hydrogen bond with the oxygen atom of Lys101. The MOM linker directs the pyridinyl ring into the eastern channel. The pyridinyl nitrogen has a favorable interaction with the NH of Val106 and also accepts a hydrogen bond from a water molecule. The 2-pyridinyl analog (not shown) has the nitrogen towards the viewer in Figure 1. Its computed binding affinity is sensitive to the presence or absence of a water molecule that can bridge between the nitrogen and MOM oxygen atoms. If a water molecule starts there in the MC simulations, it does not diffuse away. However, a JAWS analysis23 found that the water molecule has an unfavorable binding free energy and it was removed.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of 1e bound to HIV-RT from a MC/FEP simulation. Carbon atoms of 1e are in yellow. Some residues including His235, Pro236 and Tyr318 are omitted for clarity.

Alternatives to the MOM linker were considered for the oxazoles 3. MC/FEP calculations were performed to interconvert 5 XYZ possibilities (Table 3). Only the thio modifications were predicted to be more favorable than MOM. Indeed, a small gain was observed for the parent 3d vs 3a (Table 4); however, enthusiasm for pursuit of additional thio analogs was limited by likely metabolic liabilities. Reduction of the linker length to reduce potential conformational penalties on binding was also considered by BOMB-building/energy minimizations. This indicated that CH2O, O, and no linker should all be viable and likely better than MOM. The corresponding FEP modifications are not straightforward and were not pursued. However, synthesis and assaying of 3j and 3k did provide activity boosts to 0.40 and 0.19 μM.

Table 3.

MC/FEP results for optimization of the linker.

| |

|---|---|

| R′ | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

| CH2OCH2-4-Pyridinyl | 0.0 |

| CH2SCH2-4-Pyridinyl | −2.3 ± 0.27 |

| CH2CH2O-4-Pyridinyl | 1.0 ± 0.27 |

| CH2CH2S-4-Pyridinyl | −2.0 ± 0.26 |

| CH2CH2CH2-4-Pyridinyl | 1.1 ± 0.21 |

Table 4.

Anti-HIV-1 Activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50), μM

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | R′ | EC50 | CC50 |

| 3a | F | CH2OCH3 | 2.1 | 32 |

| 3b | F | CH2OCH2-2-Furanyl | 1.6 | 31 |

| 3c | Cl | CH2OCH3 | 1.2 | 8.1 |

| 3d | F | CH2SCH3 | 1.2 | >100 |

| 3e | F | CH2CH2OH | 2.7 | 35 |

| 3f | F | CH2CH2O-4-Pyridinyl | 1.1 | 11 |

| 3g | F | OCH2CH2-1-Uracilyl | 25 | 73 |

| 3h | F | CH2CH2S-2-Pyrimidinonyl | 13 | >100 |

| 3i | F | CH2OH | 3.8 | >100 |

| 3j | F | CH2O-4-Pyridinyl | 0.40 | >100 |

| 3k | F | O-4-Pyridinyl | 0.19 | 21 |

| 3l | F | O-3-Pyridinyl | 0.31 | 22 |

Motivated by this improvement, further refinements were probed. An FEP chlorine scan was performed on the anilinyl ring of 3j to ascertain if additional substitution was desirable.7 The computed ΔΔG values in Table 5 indicated that chlorination at C5 should be uniquely beneficial. A computed structure for the 5-chloro analog bound to RT is shown in Figure 2. The chlorine fills a void in the hydrophobic cavity beneath Leu234. It may also make the meta-NH a better hydrogen-bond donor towards Lys101.24

Table 5.

MC/FEP results for replacements of hydrogen by chlorine.

| |

|---|---|

| R | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

| H | 0.0 |

| 2-Cl | −0.01 ± 0.14 |

| 3-Cl | 0.12 ± 0.12 |

| 5-Cl | −2.87 ± 0.12 |

| 6-Cl | 3.65 ± 0.17 |

Figure 2.

Complex for 3n built with BOMB and energy-minimized.

Table 6 contains related assay results. For the hydroxymethyl derivatives, 3i and 3m, addition of the chlorine enhances the WT activity by a factor of 15. Indeed, a similar boost is found for the CH2O-4-pyridinyl analogs, 3j and 3n, with 3n at 30 nM. However, the predicted aqueous solubility of 3n from QikProp was below 1 μM, which is undesirable.7 Thus, the N-oxide 3o was prepared and found to be a potent NNRTI with an EC50 of 11 nM, and with a predicted solubility near 10 μM. 3r and 3s also showed improvement over 3k and 3l. The structurally novel, linker-less 3u and 3v were also prepared and show good activity. The cyano analog 3p was previously the most potent inhibitor in the oxazole series.6b Addition of the meta-chlorine brings the activity to 6 nM for 3q.

Table 6.

Anti-HIV-1 Activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50), μM

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R′ | R″ | EC50a | CC50b |

| 3m | CH2OH | 3-Cl | 0.26 | 90 |

| 3n | CH2O-4-Pyridinyl | 3-Cl | 0.030 | 3.8 |

| 3o | CH2O-4-Pyridinyl-N-oxide | 3-Cl | 0.011 | 1.7 |

| 3p | CN | H | 0.013 | 7.4 |

| 3q | CN | 3-Cl | 0.006 | 11 |

| 3r | O-4-Pyridinyl | 3-Cl | 0.12 | 21 |

| 3s | O-3-Pyridinyl | 3-Cl | 0.031 | 16 |

| 3t | O-3-Pyridinyl | 3-Br | 0.034 | 7.5 |

| 3u | 4-Pryidinyl | 3-Cl | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| 3v | 3-Pyridinyl | 3-Cl | 0.073 | 8.9 |

The Y181C and K103N/Y181C variants have been particularly problematic for NNRTI therapy,1,5 so several of the more potent NNRTIs were tested against corresponding strains of HIV-1 (Table 7). Lowmicromolar activity towards the variants is obtained with most of the compounds, which is an improvement over 3p.6b The addition of the chlorine in going from 3p to 3q also helps towards Y181C, but not with the double mutant. Though interesting alternatives to the cyano group in 3p and 3q were discovered, the ‘eastern extensions’ did not overcome well the deficiencies in performance on the variants. In comparing our computed structures to crystal structures for related NNRTIs including etravirine with azine17 rather than azole cores, the former appear to feature better contact of the western substituted phenyl groups with Y188 or W229 and less dependence on interaction with Y181.

Table 7.

Activity (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50) in μM for Variant HIV-1 Strains

| WT | Y181C | K103N/Y181C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | EC50 | CC50 | EC50 | CC50 | EC50 | CC50 |

| 3k | 0.19 | 21 | 5.0 | 17 | 12 | 17 |

| 3o | 0.011 | 1.7 | NA | 2.7 | NA | 2.1 |

| 3p | 0.013 | 7.4 | NA | 8.0 | ND | ND |

| 3q | 0.006 | 11 | 0.42 | 9.9 | NA | 8.9 |

| 3r | 0.12 | 21 | 2.3 | 17 | 7.2 | 17 |

| 3s | 0.031 | 16 | 3.2 | 16 | 4.5 | 15 |

| 3u | 0.14 | 9.3 | 3.8 | 11 | 5.6 | 9.1 |

| 3v | 0.073 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 15 | NA | 12.5 |

| d4T | 1.4 | >100 | 0.7 | >100 | 0.5 | >100 |

| nevirapine | 0.11 | >100 | NA | >100 | NA | >100 |

| evafirenz | 0.002 | >0.1 | 0.010 | >0.1 | 0.030 | >0.1 |

| etravirine | 0.001 | >0.1 | 0.011 | >0.1 | 0.005 | >0.1 |

In conclusion, extension of azole-containing NNRTIs towards the eastern portion of the binding site has yielded new anti-HIV agents. The structural range of possibilities is striking arising from variation of the linker length in, e.g., 3f, 3j, 3k, and 3u. MC/FEP calculations provided structural insights on the complexes and assisted in the discovery of inhibitors with ca. 10-nM activities towards wild-type HIV-1.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to the National Institutes of Health (AI44616, GM32136, GM49551) for support. Receipt of reagents through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH is also greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Flexner C. Nature Rev. Drug Disc. 2007;6:959. doi: 10.1038/nrd2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. Science. 1992;256:1783. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smerdon SJ, Jager J, Wang J, Kohlstaedt LA, Chirino AJ, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 1994;91:3911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Clerq E. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1297. doi: 10.1021/jm040158k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Clerq E. Nature Rev. Drug Disc. 2007;6:1001. doi: 10.1038/nrd2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Barreiro G, Kim JT, Guimaraes CRW, Bailey CM, Domaoal RA, Wang L, Anderson KS, Jorgensen WL. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5324. doi: 10.1021/jm070683u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zeevaart JG, Wang L, Thakur VV, Leung CS, Tirado-Rives J, Bailey CM, Domaoal RA, Anderson KS, Jorgensen WL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9492. doi: 10.1021/ja8019214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen WL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:724–733. doi: 10.1021/ar800236t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill AL, Frederickson M, Cleasby A, Woodhead SJ, Carr MG, Woodhead AJ, Walker MT, Congreve MS, Devine LA, Tisi D, O'Reilly M, Seavers LCA, Davis DJ, Curry J, Anthony R, Padova A, Murray CW, Carr RAE, Jhoti H. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:414. doi: 10.1021/jm049575n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsunoda T, Yamamiya Y, Itô S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klapars A, Antilla JC, Huang X, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7727. doi: 10.1021/ja016226z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antilla JC, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11684. doi: 10.1021/ja027433h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Undavia NK, Trivedi PB. J. Ind. Chem. Soc. 1989;66:60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallon GD, Francis CL, Johansson K, Liepa AJ, Woodgate RCJ. Aust. J. Chem. 2005;58:891. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin TS, Luo MZ, Liu MC, Pai SB, Dutschman GE, Cheng YC. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:171. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray AS, Yang Z, Chu CK, Anderson KS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:887. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.887-891.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorgensen WL, Ruiz-Caro J, Tirado-Rives J, Basavapathruni A, Anderson KS, Hamilton AD. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:663. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himmel DM, Das K, Clark AD, Jr., Hughes SH, Benjahad A, Oumouch S, Guillemont J, Coupa S, Poncelet A, Csoka I, Meyer C, Andries K, Nguyen CH, Grierson DS, Arnold E. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:7582. doi: 10.1021/jm0500323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1689. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen WL, Thomas LT. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:869. doi: 10.1021/ct800011m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado-Rives J. J. Am. Chem .Soc. 1996;118:11225. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:6665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408037102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel J, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15403. doi: 10.1021/ja906058w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen WL, Jensen KP, Alexandrova AN. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:1987. doi: 10.1021/ct7001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]