Abstract

Deregulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway has been implicated in numerous pathologies like cancer, diabetes, thrombosis, rheumatoid arthritis and asthma. Recently, small molecule and ATP-competitive PI3K inhibitors with a wide range of selectivities have entered clinical development. In order to understand mechanisms underlying isoform selectivity of these inhibitors, we developed a novel expression strategy that enabled us to determine the first crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of the class IA PI3K p110δ. Structures of this enzyme in complex with a broad panel of isoform- and pan-selective class I PI3K inhibitors reveal that selectivity towards p110δ can be achieved by exploiting its conformational flexibility and the sequence diversity of active-site residues that do not contact ATP. We have used these observations to rationalize and synthesize highly selective inhibitors for p110δ with greatly improved potencies.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinases are structurally closely related lipid kinases, which catalyze the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of phosphoinositide substrates1,2. Together with the serine/threonine protein kinase B (PKB), PI3Ks constitute a central signalling hub that mediates many diverse and crucial cell functions like cell growth, proliferation, metabolism and survival1,3. The observation that PI3Ks acting downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are the most commonly mutated kinases in human cancers has spurred an immense interest in understanding the structural mechanisms how these mutations upregulate PI3K activity and in developing selective and drug-like PI3K inhibitors4,5.

PI3Ks can be grouped into three classes based on their domain organisation6. Class I PI3Ks are heterodimers consisting of a p110 catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit of either the ‘p85’-type (associated with class IA PI3Ks with the isoforms p110α/β/δ) or the ‘p101/p84/p87’-type (associated with class IB PI3K p110γ). The p110 catalytic subunit consists of an adaptor-binding domain (ABD), a Ras-binding domain (RBD), a C2 domain, a helical domain and the kinase domain7-10.

Mutant mice and inhibitor studies have shown less functional redundancy for the various class I PI3K isoforms than previously anticipated. While p110α and p110β are ubiquitously expressed, p110γ and p110δ are predominantly found in haematopoietic cells11-13. Genetic deregulation of PI3K activity (oncogenic gain-of-function mutations, overexpression) has been implicated in cancer (all class I PI3K isoforms)14-17, diabetes (p110α)18, thrombosis (p110β)19, rheumatoid arthritis (p110γ and p110δ)20 and asthma (p110γ and p110δ)21,22. Consequently, the selective inhibition of individual PI3K isoforms using small molecule and ATP-competitive inhibitors is a promising therapeutic strategy23. However, since all active-site side chains in contact with ATP are completely conserved throughout all class I PI3K family members (Supplementary Fig. 1), this is a challenging objective. Furthermore, in order to minimize undesired and often poorly understood toxic side effects, such inhibitors ideally would have to show no cross-reactivity towards off-pathway targets24.

The earliest generation of small molecule and ATP-competitive PI3K inhibitors including the pan-selective LY29400425 and wortmannin26 were important tools to investigate PI3K-mediated cellular responses in the laboratory but their low affinities (LY294002), instability (wortmannin) as well as non-selectivity and toxicity limited their clinical use. However, further chemical modifications of some of these early inhibitors significantly helped to improve their drug-like properties. For example, PWT-458 (Wyeth) and PX-866 (Oncothyreon) are modified wortmannin-based PI3K inhibitors with improved pharmacological properties that are currently in phase I clinical trials27,28.

The first crystal structures of p110γ in complexes with pan-selective PI3K inhibitors29 made it possible to begin to rationalize PI3K isoform-selective inhibitors like AS604850 (Merck-Serono) for p110γ30. However, many of these inhibitors retained off-target activities and, partially due to the lack of crystal structures of other PI3K isoforms and PI3K related protein kinases (PIKKS), these unwanted side effects were difficult to rationalize.

Noteworthy, the development of multi- and pan-selective PI3K inhibitors as well as dual PI3K/mTOR or PI3K/tyrosine kinase31 rather than isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors remains a valid therapeutic strategy. XL-147 (Exelixes), which is currently evaluated in combination with other cancer therapeutics is in phase I/II clinical trials for the treatment of non-small lung cancer and GDC-0941 (Roche)32, also in phase I trials for the treatment of breast cancer33, are examples of pan class I selective PI3K inhibitors. NVP-BEZ235 (Novartis), currently in phase I/II trials for breast cancer34 and SF1126 (Semaphore), a RGDS peptide conjugated prodrug of LY294002 in phase I trials35 are examples of dual-selectivity PI3K/mTOR inhibitors.

Recently, several new class I PI3K isoform-selective inhibitors showing improved selectivities and potencies have been reported and some of them have entered clinical trials: CAL-101 (Calistoga), a derivative of the highly p110δ-selective inhibitor IC8711436 with increased potency, entered stage I clinical trials for the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and B-cell chronic lymphoid leukaemia (CLL). The p110β-selective AZD6482 (AstraZeneca) is in clinical phase I for the treatment of thrombosis. Strikingly however, despite a growing list of such isoform-selective compounds, little is known about what determines isoform-selectivity on a structural level.

Impaired PI3Kδ signalling results in severe defects of innate and adaptive immune responses and suggested that targeting of this isoform would be a beneficial therapeutic strategy20,24. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of isoform-selectivity of PI3Kδ inhibitors, we report the crystal structure of the catalytic core of p110δ, both free and in complexes with a broad panel of novel and mostly p110δ-selective PI3K inhibitors. Our study provides the first detailed structural insights into the active site of a class IA PI3K occupied by non-covalently bound inhibitors. Furthermore, our structures suggest mechanisms to achieve p110δ selectivity and to increase potency of inhibitors without sacrificing isoform-selectivity. To obtain these structures, we developed a unique expression and purification scheme that has now been extended to all class IA PI3K isoforms.

With our new set of p110δ crystal structures and better models of flexibility resulting from molecular dynamics simulations we are now starting to understand why p110δ can be more easily deformed to open an allosteric pocket in which p110δ-selective inhibitors can be accommodated.

RESULTS

Expression, purification and catalytic activity of ΔABDp110δ

Our initial attempts to express either the full-length or the ABD-truncated p110δ catalytic subunit in Sf9 cells produced only insoluble protein. However, we could readily express and purify p110δ in complexes with only the iSH2 domain of p85α. We devised a novel expression and purification strategy by introducing a TEV protease cleavage site in the linker region between the ABD and the RBD of p110δ (Fig. 1a) with the objective of generating an ABD-truncated version for crystallization trials. The ΔABDp110δ construct showed significantly enhanced lipid kinase activity in vitro when compared with either the holo p110δ/p85α or the p110δ/nicSH2 complex (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Domain organization, construct design and overall crystal structure of p110δ. A) A TEV protease cleavage site was introduced between residues 105 and 106 of the p110δ ABD-RBD linker. The numbers below the boxes correspond to the indicated domain boundaries. After purification of the p110δ/iSH2 complex, the catalytic core is released by cleavage with TEV protease. B) Cartoon representation of the overall co-crystal structure of the ΔABDp110δ/PIK-39 complex. Linker regions are colored in white, the RBD in salmon, the C2 domain in cyan, the helical domain in green, the kinase domain N-lobe in red and the kinase domain C-lobe in yellow. PIK-39 is shown in light blue as a ball and stick representation. Selected secondary structure elements of the kinase domain are labeled.

Overall structure of ΔABDp110δ

Crystallographic statistics for all p110δ datasets are given in Supplementary Table 1. The overall fold of p110δ is very similar to the catalytic subunits of p110γ and p110α (Fig. 1b)8,37. The helical ABD-RBD linker packs tightly against the helical domain and bridges the Ras-binding and the C2 domain. Helices kα1 and kα2/kα2′ form a hairpin in the N-lobe that sits on top of a five-stranded β-sheet formed by kβ3-kβ7, and this hairpin structurally distinguishes PI3Ks from protein kinases. These helices extend the antiparallel A/B pairs of α-helices found in the helical domain. The kinase domain has an extensive, tightly packed interface with the helical domain. All of the catalytically important motifs within this domain are well ordered with the exception of residues 920-928 of a region known as the “activation” or phosphoinositide-binding loop. Remarkably, the residues within the p110δ 893-DRH-895 motif located in the “catalytic” loop, a motif conserved in all PI3Ks and inverted (HRD) in protein kinases, adopt a different conformation from what was previously observed in the structure of p110γ (Supplementary Fig. 3)8. This different conformation might be critical for the correct positioning of the DFG aspartate at the beginning of the “activation” loop.

All the domains of p110δ superimpose closely on previously reported structures (Supplementary Fig. 4a-f). However, the most striking difference in the overall structure of p110δrelative to p110αor p110γ is a change in the orientation of the N-lobe with respect to the C-lobe of the kinase domain. This shift may reflect motions characteristic of the catalytic cycle, analogous to the hinging and sliding motions of the N- and C-lobes have been described for protein kinases38. Furthermore, the RBD shifts relative to the N-lobe of the kinase domain (Supplementary Fig. 4g). The RBD mediates interaction with Ras in a GTP-dependent manner for all three isoforms11,12,39,40. Despite the great sequence divergence among the isoforms in the RBD, the overall RBD backbone conformation is very closely preserved among the various class I isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 4f). However, differences in the orientation of the RBD relative to the kinase domain suggest the possibility of different mechanisms of activation by Ras. The conformation of the loop connecting kβ4 and kβ5 (Tyr763 to Val774 in p110δ) in the N-lobe is remarkably different in all the isoforms (longest in p110α, shortest in p110δ) and this correlates with the orientation of the RBD. Within the RBD of p110δ residues 231-234 are disordered. The equivalent region in p110α is an ordered helix (Rα2), whereas in p110γ this region is ordered only in the Ras/p110γ complex, although it has a completely different conformation than in p110α.

Co-crystallization of p110δ with inhibitors

We chose a set of chemically diverse inhibitors in order to understand structural mechanisms that underlie p110δ-specific inhibition in contrast to broadly specific PI3K inhibitors. Even though we obtained crystals grown in the presence of ATP, only a weak density somewhat larger than what would be expected for an ordered water molecule was observed in the hinge region. We will refer to this structure as the apo-form of p110δ.

ATP-binding pocket

All of the compounds presented here contact a core set of six residues in the ATP-binding pocket (Supplementary Table 2), and - apart from the hinge residue Val827 in p110δ - these residues are invariant in all of the class I PI3K isotypes. Based on our inhibitor-bound structures of p110δ as well as previously described PI3K complexes18,29,30,32,41, we can define four regions within the ATP-binding pocket that are important for inhibitor binding (Fig. 2a): An “adenine” pocket (hinge), a “specificity” pocket, an “affinity” pocket and the hydrophobic region II located at the mouth of the active-site18,42. Of the core active-site residues, only two are in contact with inhibitors in all complexes: Val828 and Ile910. Residues 825-828 line the “adenine” pocket and form a hinge between the N-lobe and C-lobe of the catalytic domain. The backbone amide of the hinge Val828 makes a characteristic hydrogen bond in all of the p110/inhibitor complexes. Additionally, the backbone carbonyl of hinge Glu826 establishes hydrogen bonds to most of the inhibitors.

Figure 2.

The propeller-shaped p110δ-selective inhibitors induce the formation of the “specificity” pocket. Shown are the active sites of p110δ in complex with the inhibitors IC87114 (a), PIK-39 (b), SW13 (c), SW14 (d) and SW30 (e). Key residues that outline the active site and interact with the compounds and the 2mFo-DFc electron densities (contouring level 1σ) are presented. Selected water molecules in the active sites are shown as gray spheres. Note, that IC87114 and PIK-39 do not fill the “affinity” pocket, whereas SW13, SW14 and SW30 do. Dashed black lines represent hydrogen bonds.

Our selection of inhibitors can be organized into three types: Firstly, inhibitors that adopt a propeller-shaped conformation (two roughly orthogonal oriented aromatic ring systems) when bound to the enzyme (Fig. 2a-e and Supplementary Fig. 5). These are mostly p110δ-selective inhibitors, which stabilize a conformational change that opens a hydrophobic “specificity” pocket in the active site that is not present in the apo-structure of the enzyme as previously reported for the p110γ/PIK-39 crystal structure18. Secondly, we co-crystallized the p110δ enzyme with a set of mostly flat and multi- to pan-selective class I PI3K inhibitors that do not provoke such a conformational rearrangement. AS15, which has a distorted propeller-shape when bound to the enzyme, is the only member of a third type of inhibitor, which is highly selective for the p110δ isoform, although it does not open the “specificity” pocket.

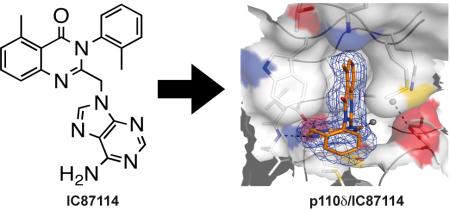

The propeller-shaped p110δ-selective inhibitors IC87114 and PIK-39

The discovery of the p110δ-selective inhibitor IC87114 (ICOS) in 200336 was a proof-of-principle that isoform-selectivity of PI3K inhibitors can be accomplished, and to date, it remains one of the most selective p110δ inhibitors known.

The crystal structures of the p110δ/IC87114 (compound 1) (Fig. 2a) and the p110δ/PIK-39 (compound 2) (Fig. 2b) complexes show that the purine group of the compounds resides within the “adenine” pocket and establishes hydrogen bonds to the hinge residues Glu826 and Val828. The quinazolinone moiety is sandwiched into the induced hydrophobic “specificity” pocket between Trp760 and Ile777 on one side and two P-loop residues, Met752 and Pro758 on the other side. The “specificity” pocket is not present in the apo enzyme where the P-loop Met752 rests in its “in” position leaning against Trp760. The toluene group (IC87114) and the methoxyphenyl group (PIK-39) attached to the quinazolinone moiety project out of the ATP-binding pocket over a region that we will refer to as hydrophobic region II.

PIK-39 binding to both p110δ and p110γ induces a slight opening in the ATP-binding pocket. The p110δ ATP-binding pocket accommodates the PIK-39-induced conformational change by a local change in the conformation of the P-loop (residues 752-758 in p110δ) whereas the equivalent opening of the p110γ pocket is accompanied by a conformational change that involves much of the N-lobe moving with respect to the C-lobe. The loop between kα1 and kα2 of p110γ (residues 752-760) sits on top of the P-loop (residues 803-811) and appears to rigidify it, so that the compound-induced opening of the pocket is accompanied by a shift of the N-lobe as a unit (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). In contrast to p110γ, in p110δ the slightly shorter kα1-kα2 loop leaves the P-loop largely free and able to move independently of the rest of the N-lobe. We proposed that opening of the “specificity” pocket might be easier in p110δ compared to p110γ.

Molecular dynamics simulations and free energy perturbation speak to the greater flexibility of p110δ compared with p110γ

Perturbation analysis by molecular dynamics simulations suggests that the free energy of the “specificity” pocket closure is more favourable in p110γ than p110δ (Supplementary Fig. 7). To quantify the higher degree of flexibility within the p110δ active site we performed molecular dynamics simulations of the apo enzymes of both isoforms (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Movies 3 and 4). The potential energy of the interaction of PIK-39 with the enzyme is more favourable for p110δ than for p110γ (Supplementary Fig. 8). Our results further show that the distance between Trp760 (Trp812 in p110γ) and the P-loop Met752 (Met804 in p110γ) does not change appreciably in p110δ over the course of the simulation because the conformational changes observed for both residues are synchronized with each other, i.e. the tryptophan smoothly follows the methionine and vice versa. In contrast, in p110γ, as the Met804 transiently assumes alternate rotamers, it briefly creates gaps between itself and Trp812. Trp812 of p110γ is sterically constrained by a hydrogen bond to Glu814 (Met762 in p110δ) and is therefore unable to flex in synchrony with Met804 as in p110δ. Additionally, in p110γ there is a more pronounced hydrophobic interaction between the Trp812 and the hinge Ile881, which might further restrain the position of the tryptophan. The transient opening of the “specificity” pocket in p110γ would allow water to become trapped, leading to an unfavourable entropy change.

Mechanisms to increase potencies of propeller-shaped p110δ-selective inhibitors

The SW series (compounds 3-5) (Williams O. & Shokat K. M. et al., submitted) and INK series (compounds 6-7) of inhibitors take advantage of both the “specificity” pocket and the “affinity” pocket (synthesis details for these compounds are given in the Supplementary Methods section). This pocket is lined by a thin hydrophobic strip formed by Leu784, Cys815 and Ile825 at the back of the ATP-binding pocket and flanked on the top by the side chain of Pro758 and Lys779 and on the bottom by Asp787 (hydrophobic region I in protein kinases). These mostly p110δ-selective compounds (SW14 is dual-selective for p110γ/δ) are also propeller-shaped, but have additional decorations when compared to IC87114 and PIK-39 in the form of an ortho-fluorophenol (SW14), a para-fluorophenol (SW13) or a butynol group (SW30) attached to the central pyrazolopyrimidinineamine scaffold (Fig. 2c-e). These groups explore the “affinity” pocket where they engage in hydrogen bonds with Asp787 (SW13/14/30) and Lys779 (SW13/14). Additionally, the butynol OH group of SW30 also serves as a hydrogen bond donor to the DFG Asp911 at the start of the “activation” loop, and the phenolic OH group of SW13 engages in hydrogen bonding with Tyr813. This set of novel inhibitor-enzyme interactions leads to a significant increase in the inhibitors’ potencies towards p110δ, which is reflected in their greatly lowered IC50 values (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). The propeller-shape of a compound alone does not guarantee p110δ specificity as shown by INK666 (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Our structures of p110δ in complex with SW13/14/30 also speak to a conformational flexibility for the catalytical DFG Asp911. This residue assumes two alternative conformations in the p110δ/SW structures. One of these, the “in” conformation, coincides with its putative ATP/Mg2+-binding position (based on the p110γ/ATP complex). The other conformation has the DFG Asp911 swung away (“out” conformation). In the p110δ/SW14 and p110δ/SW30 structures, DFG Asp911 is found in the “out” conformation, while in the p110δ/SW13 complex it is “in”. In protein kinases, a shift of the DFG aspartate from the in-conformation (ATP-bound) to the out-conformation is characteristic of the catalytic cycle. By analogy, it may be that these inhibitors are inducing conformations characteristic of the PI3K catalytic cycle.

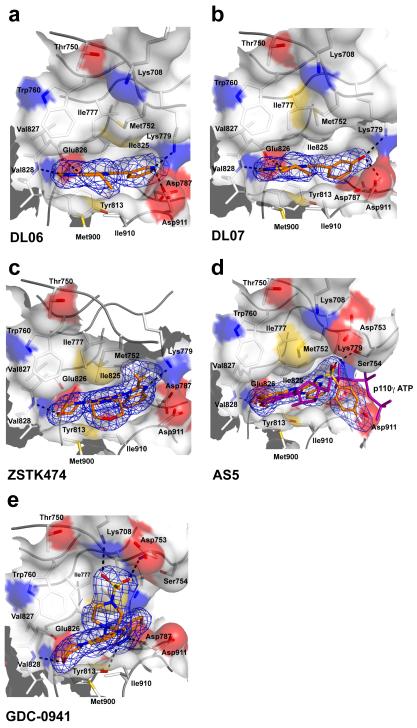

p110δ in complex with flat and multi-selective class I PI3K inhibitors

ZSTK47443 (compound 8), DL06 (compound 9), DL07 (compound 10), AS5 (compound 11) and GDC-094132 (compound 12) are fairly flat compounds that do not open the “specificity” pocket and achieve relatively little isotype selectivity. Their binding provokes some motions of the P-loop side chains of p110δ, and these conformational changes are coordinated with changes in conformation of the DFG Asp 911 in the C-lobe.

The DL06/07 inhibitors represent a minimalistic approach to achieve PI3K inhibition

The DL06/07 series of PI3K inhibitors (Williams O. & Shokat K. M. et al., submitted) can best be described as pan-selective p110 inhibitors, which represent a minimalistic approach to achieve PI3K inhibition (see Supplementary Methods for synthesis details). They are flat and small compounds with a minimal design just sufficient enough to span the “adenine” pocket via their pyrazolopyrimidine moiety and project into the “affinity” pocket by means of a phenol (DL07) or a pyridine (DL06) group attached to a propyne “stick” (Fig. 3a,b). The DL07 phenol group interacts with the DFG Asp911, forcing it to its “in” conformation. It also induces rotations in the side chain of P-loop Met 752, but not to its “out” conformation. Similar interactions are formed by DL06.

Figure 3.

The flat inhibitors DL06, DL07, ZSTK474, AS5 and GDC-0941 are multi- to pan-selective class I PI3K inhibitors that do not induce the opening of the “specificity” pocket. Shown are the binding modes of DL06 (a), DL07 (b), ZSTK474 (c), AS5 (d) and GDC-0941 (e) in the active site of p110δ. Met752 is in its “in” position for all these compounds. For panel (d), the structure of the p110γ/ATP complex (PDB entry 1e8x) was superimposed on the Cα-backbone of p110δ to show the proximity of the sulfonyl group of AS5 to the alpha phosphate group of ATP (purple). This sulfonyl group is a hydrogen bond acceptor to Ser754 located in the P-loop of p110δ. (e) GDC-0941 is a pan-class IA PI3K inhibitor that (like AS15) interacts with residues outside the active site. GDC-0941 occupies the “adenine” pocket and the “affinity” pocket within the active site of p110δ and engages there in hydrogen bonds with Val828, Tyr813 and Asp787. Additionally, the substituted piperazine group of GDC-0941 extends out of the ATP-binding site where its methylsulfonyl moiety acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor for Asp753 of the P-loop and Lys708 at the beginning of kα2. The contouring level of the 2mFo-DFc electron densities is 1σ for each compound.

p110δ/ZSTK474

Yaguchi et al. discovered and characterized the novel pan-selective triazine PI3K inhibitor ZSTK474, which strongly inhibits the growth of tumor cells in human cancer xenografts and therefore is a potential candidate for further clinical development43. Its crystal structure in complex with p110δshows it flipped over relative to what was predicted in a computational p110γ/ZSTK474 model43 (Fig. 3c). The oxygen of one of the morpholino groups is positioned as the hinge hydrogen bond acceptor and the morpholino ring adopts a chair conformation. The benzimidazole group extends into the “affinity” pocket where its nitrogen acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor for the primary amine of Lys779. The difluoromethyl group points towards Pro758 in the upper wall of the hydrophobic “affinity” pocket. The second morpholino group adopts a somewhat twisted chair conformation and projects out of the ATP binding pocket in a same manner as the phenyl group of LY294002 where it occupies the hydrophobic region II.

AS5 reveals the potential of phosphate-mimetics as kinase inhibitors

AS5 is a relatively flat p110α/p110δ dual-selectivity inhibitor with only modest affinities for these two isoforms. Its dimethoxyaniline group occupies the “adenine” pocket, where it interacts with the hinge Val828, but does not project deeply into the “affinity” pocket (Fig. 3d). It is conceivable that modifications on this scaffold that target polar moieties within the “affinity” pocket could increase potencies of AS5 derivatives. Coupled to the quinoxaline group is a p-fluorobenzenesulfonamide, and when superimposed on the p110γ/ATP crystal structure it becomes apparent that the sulfonyl group of AS5 co-localizes with the α-phosphate group of ATP. This compound reveals two strategies to mimic the ATP phosphates to achieve inhibition of p110α and p110δ. Firstly, one of the sulfonyl oxygens of AS5 is a hydrogen bond acceptor for P-loop Ser754. Secondly, the fluorophenyl group exits the active site close to the DFG Asp911, in the proximity of the space occupied by the β/γ-phosphates in the p110γ/ATP structure.

GDC-0941 shows use of the space above hydrophobic region II for moieties that confer better drug-like properties

The identification characterization and development of the tricyclic pyridofuropyrimidine lead PI-10344-46, a very potent dual-selective PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, has led to the pan-selective class I PI3K thienopyrimidine inhibitor GDC-0941, which has no off-target activity against mTOR32. GDC-0941 is orally bioavailable and currently in phase I trials for the treatment of solid tumors33.

Its structure in complex with p110δ (Fig. 3e) confirms the previously described binding mode to p110γ32 but also reveals interesting new features. Whereas the piperazine ring adopts a twisted chair conformation in the p110γ structure, it is present in a distorted boat conformation in the structure of p110δ. The terminal methanesulfonylpiperazine group is also oriented differently in both structures. In p110δ, this group is marginally tilted with respect to the central thienopyrimidine scaffold and thereby comes closer to the P-loop. Instead of the Lys802-p110γ (Arg770-p110α), the Thr750 at the equivalent position in p110δ is unable to establish a hydrogen bond to the inhibitor’s sulfonyl oxygen. However, a different lysine residue (kα2 Lys708) interacts with the sulfonyl group of GDC-0941, thereby indicating why this compound does not lose affinity for p110δ.

AS15 is a non-propeller-shaped and highly p110δ–selective inhibitor that exploits non-conserved residues outside of the active-site

Although AS15 (compound 13) is chemically related to the quinazolinone purine inhibitor PIK-39, its co- crystal structure with p110δ reveals an unexpected mode of binding (Fig. 4). Instead of wedging in between the Met752 and Trp760, the tetrahydroquinazolinone group presses tightly against Met752 (in its ‘in’ position) and Trp760. By comparing the binding modes of PIK-39 and AS15 to p110δ, three reasons can be deduced why PIK-39, but not AS15, is able to induce the “specificity” pocket. Firstly, whereas the purine group of PIK-39 acts as a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, the AS15 quinoxaline group interacts only with the backbone amide of hinge Val828. Secondly, the non-planar nature of the hexahydroquinazolinone may exceed the capacity of the “specificity” pocket. In its alternate location, the hexahydroquinazolinone packs into a shallow dimple formed between Met752, the small side chain of Thr750 and Trp760. In other p110 isotypes, the residue equivalent to Thr750 is a lysine or arginine. This interaction may account for the extraordinary isotype selectivity of this compound. Thirdly, compared with the shorter thiomethyl linker of PIK-39, the longer methylthioacetamide linker of AS15 might be more conformationally restrained due to the planar nature of the linker’s peptide bond. This planarity might prevent the tetrahydroquinazolinone from being positioned in a way that would allow for the induction of the “specificity” pocket.

Figure 4.

Binding mode of the p110δ-selective PI3K inhibitor AS15 and comparison of AS15 with the propeller-shaped inhibitor PIK-39 (2mFo-DFc contouring level 1σ). (a) The highly p110δ-selective compound AS15 does not open the “specificity” pocket and makes extensive use of a hydrophobic patch between Trp760, Thr750 and Met752 adjacent to the adenine-binding pocket. (b) Chemical structures of the highly p110δ-selective inhibitors AS15 and PIK-39. (d) Superposition of the AS15 and PIK-39 to demonstrate their different mode of binding within the active site of p110δ.

A number of additional p110δ-specific interactions are formed in a manner whereby the ketone oxygen from the tetrahydroquinazolinone group acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor for the backbone amide of the P-loop Asp753 and for the primary amine of Lys708. The P-loop Asp753 is specific to p110δ (the corresponding residue is Ser773 in p110α and Ala805 in p110γ), and Lys708, which is located outside of the active site, has an equivalent only in p110α (Lys729) but not in p110γ (Ser 760). Since AS15 does not occupy the “affinity” pocket, modifications of the compound exploring this pocket should result in an increased potency for p110δ.

DISCUSSION

The p110δ/inhibitor crystal structures presented here show that selectivity can be achieved by exploiting both differences in flexibilities among the isoforms and isotype-specific contacts beyond the first-shell of residues that interact with ATP. Flexibility-based inhibitors are generally able to utilize the inherently greater pliability of the p110δ P-loop. All propeller-shaped inhibitors create a new “specificity” pocket not present in the apo-form of the enzyme. Small modifications of this framework (as found in AS15) can result in inhibitors that are highly selective by establishing unique p110δ-specific interactions without the formation of the “specificity” pocket. The plasticity of p110δ may enable this isoform to more readily accommodate even very rigid compounds. Our structures also suggest that introducing moieties interacting with the hydrophobic region II at the mouth of the active site might help to improve pharmacokinetic properties of drug-like PI3K inhibitors such as GDC-0941.

Initial molecular dynamic simulations suggest that allosteric pockets, such as the “specificity” pocket can be identified with computational approaches. A similar method that imposes stress on the ATP-binding pocket may identify new strain-prone regions that could be exploited by inhibitors.

The strategy to explore the “affinity” pocket is a very powerful approach to augment potency of inhibitors while maintaining selectivity. Further development of selective inhibitors for other isotypes and for overcoming potential resistance mutations that frequently accompany treatment with inhibitors will require a broader range of PI3K and PIKK structures.

METHODS

Construct design, expression and purification of ΔABDp110δ

Briefly, the TEV-insertion construct was generated using the overlapping PCR method, digested with BglII and XhoI at sites encoded by the primers and ligated into pFastBac-HTa (Invitrogen) cut with the BamHI and XhoI restriction enzymes (NEB). The correct insertion of the TEV-site was confirmed by DNA-sequencing (amino acid sequence: 101-LVARE-(105)-ENLYFQG-(106)-GDRVKK-111). The construct has an N-terminal extension encoded by the vector (MSYHHHHHHDYDIPTTENLYFQGAMDL) preceding the first residue of p110δ. This extension has a His6-tag and an additional vector-encoded TEV-cleavage site. Recombinant baculovirus was generated and propagated according to standard protocols. For expression, Sf9 insect cells at a density of 1×106/ml were co-infected with an optimised ratio of viruses encoding the catalytic and regulatory subunit. As a regulatory subunit, we used the iSH2 fragment of the human p85α (residues 431-600), tagged with an N-terminal, non-cleavable His6-tag. The culture was incubated for 48 h after infection, cells harvested and washed with ice-cold PBS, flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −20°C. For purification, cell pellets corresponding to typically 8 litres of culture were defrosted and resuspended in 250 ml of buffer A (20 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol and 2 mM β-ME). After addition of 2 tablets of Complete EDTA-free Proteinase Inhibitors (Boehringer) the suspension was sonicated and the lysate spun at 42000 rpm for 45 min. The supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm filter units (Sartorius) and loaded onto a 5 ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare). After a wash step with buffer A the column was eluted using a gradient from 0-100% buffer B (buffer A + 500 mM imidazole). The p110δ/iSH2fractions were pooled and loaded onto a 5 ml heparin column equilibrated with heparin A buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-ME). The column was washed and eluted with a gradient from 0-100% heparin B buffer (heparin A + 1 M NaCl). This chromatography step resulted in a separation of excess His6-tagged iSH2 (earlier peak) from the p110δ/iSH2 complex (later peak). The p110δ/iSH2fractions were pooled and adjusted to 5 mM β-ME. TEV proteinase at a w/w ratio of 1:10 was added and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. After verifying that the cleavage reaction was complete, the solution was adjusted to 30 mM imidazole, passed over a second 5 ml HisTrap column to remove the ABD/His6-iSH2, and ΔABDp110δ was collected in the flow-through. Following a concentration step using Vivaspin 20 concentrators with a 50 kDa MWCO (Vivascience), the protein was subjected to gel filtration on an S200 16/60 HiLoad column (GE Healthcare) and eluted in 20 mM Tris pH 7.2, 50 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 1% (w/v) betaine, 0.02% (w/v) CHAPS and 5 mM DTT. Finally, fractions were pooled and concentrated to 4.5-5 mg/ml as determined spectrophotometrically using the extinction coefficient 129,810 M−1cm−1 at 280 nm, flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C. We have applied this strategy to all other class IA isoforms (not shown).

Synthesis and characterization of SW13/14/30 and DL06/07

A detailed description for the synthesis and characterization of these compounds can be found in the Supplementary Methods section.

X-ray crystallography

High-quality diffraction data of ΔABDp100δ crystals grown in the presence of inhibitors were obtained using a microseeding protocol implemented on our robotic setup. All crystal structures were solved by molecular replacement. See Supplementary Methods for additional details.

Lipid Kinase Activity Assay

To compare of the PI3K lipid kinase activity of the crystallized murine ΔABDp110δ construct with the full-length murine p110δ/murine p85α complex and the murine p110δ/ human p85α nicSH2 construct, a Transcreener ADP Assay (Bellbrook Labs) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, for the generation of the ADP/ATP standard curve, 10 μl of a 60 μM ADP/ATP (2x) mixture of various ADP:ATP concentrations were mixed with 5 μl of anti-ADP antibody at 80 μg/ml (4x) and 5 μl of ADP Alexa633 tracer at 40 nM (4x) in a low-volume, black and round bottom Corning 384-well plate (Corning). The plate was protected from light and shaken at 500 rpm for one hour prior to polarization measurements using a PHERAstar (BMG Labtech) fluorescence polarization microplate reader (λexc=612 nm, λem=670 nm). For the kinase reaction, 10 nM of enzymes were incubated for 1 hour at 25°C in a buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 4 mM MgCl2, 2mM EGTA, 30 μM diC8-PIP2 (Echelon) and started by the addition of 30 μM ATP (Sigma-Aldrich, neutralized). The control included the same components with the exception of the diC8PIP2 substrate. The reaction was stopped by mixing 10 μl of the kinase reaction with 10 μl of the Stop & Detect buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 40 mM EDTA, 0.2% Brij-35) containing 20 nM ADP Alexa633 tracer (2x) and 40 μg/ml ADP antibody (2x). To allow for signal stabilization, the plate was shaken at 500 rpm for 1 hr prior to fluorescence polarization measurements. The data were plotted and fitted in Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software) using an exponential decay function.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the beamline scientists and members of staff at the ESRF beamlines ID14-1, ID14-2, ID14-4, ID23-1, ID29, BM30A (Grenoble, France), the Swiss Light Source (SLS) beamline X06SA (Villigen, Switzerland) and the Diamond beamline I02 (Oxfordshire, UK). We are grateful to M. Allen for collecting the p110δ/ZSTK474 dataset and to O. Perisic for her help with the manuscript and for numerous contributions to this study. Part of this material is based on work supported under an NSFGRF to O.W. and was supported by the Graduate Research and Education in Adaptive bi-Technology Training Program of the UC Systemwide Biotechnology Research and Education Program, grant # 2008-005 to O.W. A.B. is supported by Merck-Serono, Geneva.

PDB Accession codes. Coordinates of all p110δ structures and accompanying structure factors have been deposited under the following accession codes: 2wxe (p110δ/IC87114), 2wxf (p110δ/PIK-39), 2wxg (p110δ/SW13), 2wxh (p110δ/SW14), 2wxi (p110δ/SW30), 2wxj (p110δ/INK654), 2wxk (p110δ/INK666), 2wxl (p110δ/ZSTK474), 2wxm (p110δ/DL06), 2wxn (p110δ/DL07), 2wxo (p110δ/AS5), 2wxp (p110δ/GDC-0941), 2wxq (p110δ/AS15) and 2wxr (apo-p110δ).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTEREST

Yi Liu, Ph.D. and Christian Rommel, Ph.D. are employees of Intellikine Inc, which is involved in the discovery and development of therapeutics for the prevention and treatment of human diseases.

OW and KMS are inventors on a UCSF owned patent application covering the SW series of compounds. This patent application is licensed to Intellikine Inc. KMS is a consultant and stockholder of Intellikine Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanhaesebroeck B, et al. Synthesis and function of 3-phosphorylated inositol lipids. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:535–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Class I PI3K in oncogenic cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2008;27:5486–5496. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundstrom TJ, Anderson AC, Wright DL. Inhibitors of phosphoinositide-3-kinase: a structure-based approach to understanding potency and selectivity. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:840–850. doi: 10.1039/b819067b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miled N, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domin J, Waterfield MD. Using structure to define the function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase family members. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD. Signaling by distinct classes of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:239–254. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker EH, Perisic O, Ried C, Stephens L, Williams RL. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signalling. Nature. 1999;402:313–320. doi: 10.1038/46319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katso R, et al. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:615–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chantry D, et al. p110delta, a novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit that associates with p85 and is expressed predominantly in leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19236–19241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanhaesebroeck B, et al. P110delta, a novel phosphoinositide 3-kinase in leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4330–4335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghigo A, Hirsch E. Isoform selective phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma and delta inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2008;2:1–10. doi: 10.2174/187221308783399270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang S, Denley A, Vanhaesebroeck B, Vogt PK. Oncogenic transformation induced by the p110beta, -gamma, and -delta isoforms of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1289–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickey FB, Cotter TG. BCR-ABL regulates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-p110gamma transcription and activation and is required for proliferation and drug resistance. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2441–2450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sujobert P, et al. Essential role for the p110delta isoform in phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation and cell proliferation in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:1063–1066. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight ZA, et al. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell. 2006;125:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson SP, et al. PI 3-kinase p110beta: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rommel C, Camps M, Ji H. PI3K delta and PI3K gamma: partners in crime in inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and beyond? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:191–201. doi: 10.1038/nri2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda M, et al. Allergic airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and remodeling do not develop in phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma-deficient mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SJ, Min KH, Lee YC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta inhibitor as a novel therapeutic agent in asthma. Respirology. 2008;13:764–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Chemically targeting the PI3K family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:245–249. doi: 10.1042/BST0350245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ameriks MK, Venable JD. Small molecule inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) delta and gamma. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:738–753. doi: 10.2174/156802609789044434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A Specific Inhibitor Of Phosphatidylnositol 3-Kinase, 2-(4- Morpholinyl)-8-Phenyl-4h-1-Benzopyran-4-One (Ly294002) Journal Of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arcaro A, Wymann MP. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem. J. 1993;296:297–301. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu K, et al. PWT-458, a novel pegylated-17-hydroxywortmannin, inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling and suppresses growth of solid tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:538–545. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.5.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ihle NT, et al. Molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of PX-866, a novel inhibitor of phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker EH, et al. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol Cell. 2000;6:909–919. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camps M, et al. Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 2005;11:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apsel B, et al. Targeted polypharmacology: discovery of dual inhibitors of tyrosine and phosphoinositide kinases. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:691–699. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folkes AJ, et al. The identification of 2-(1H-indazol-4-yl)-6-(4-methanesulfonylpiperazin-1-ylmethyl)-4-morpholin -4-yl-thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidine (GDC-0941) as a potent, selective, orally bioavailable inhibitor of class I PI3 kinase for the treatment of cancer. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5522–5532. doi: 10.1021/jm800295d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raynaud FI, et al. Biological properties of potent inhibitors of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases: from PI-103 through PI-540, PI-620 to the oral agent GDC-0941. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1725–1738. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maira SM, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garlich JR, et al. A vascular targeted pan phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor prodrug, SF1126, with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:206–215. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadhu C, Masinovsky B, Dick K, Sowell CG, Staunton DE. Essential role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta in neutrophil directional movement. J Immunol. 2003;170:2647–2654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang CH, et al. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318:1744–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornev AP, Haste NM, Taylor SS, Eyck LF. Surface comparison of active and inactive protein kinases identifies a conserved activation mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17783–17788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607656103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Viciana P, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase as a direct target of Ras. Nature. 1994;370:527–532. doi: 10.1038/370527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pacold ME, et al. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell. 2000;103:931–943. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandelker D, et al. A frequent kinase domain mutation that changes the interaction between PI3Kalpha and the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16996–17001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams R, Berndt A, Miller S, Hon WC, Zhang X. Form and flexibility in phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:615–626. doi: 10.1042/BST0370615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaguchi S, et al. Antitumor activity of ZSTK474, a new phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:545–556. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan QW, et al. A dual PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayakawa M, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of pyrido[3′,2′:4,5]furo[3,2-d]pyrimidine derivatives as novel PI3 kinase p110alpha inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:2438–2442. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raynaud FI, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5840–5850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.