Abstract

Recovery from schizophrenia has been conceptualized to involve not only symptom remission of symptoms and achievement of psychosocial milestones but also subjective changes in how persons appraise their lives and the extent to which they experience themselves as meaningful agents in the world. In this paper we review the potential of individual psychotherapy to address these more subjective aspects of recovery. Literature on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for persons with schizophrenia is discussed and two different paths by which psychotherapy might modify self-experience are described. First we detail how psychotherapy could be conceptualized and tailored to help persons with schizophrenia to construct richer and fuller narrative accounts of their lives including their strengths, challenges, losses and hopes. Second we explore how psychotherapy could target the capacity for metacognition or thinking about thinking, assisting persons with psychosis to become able to think about themselves and others in a generally more complex and flexible manner. The needs for future research are discussed along with a commentary on how current evidence- and skill-based treatments may contain key elements which could be considered psychotherapeutic.

Keywords: schizophrenia, recovery, psychotherapy, metacognition, self

In the mid to later part of the twentieth century, people with schizophrenia and other forms of severe mental illness were seen as inevitably having a poor prognosis, and stability or the absence of negative events such as hospitalizations or interpersonal conflict were seen as the best possible realistic outcomes. As described in several recent reviews, however, contrary to these pessimistic views, most people with severe mental illness do not experience unremitting lifelong dysfunction. (Bellack, 2006; Harrow et al., 2005: Lysaker & Buck, 2008a; Silverstein, Spaulding & Menditto, 2006). Results of large scale studies detailed in these reviews reveal that most with this condition can move meaningfully toward or achieve recovery over the course of their lives. As a consequence, recovery is now understood internationally as the focus and expected endpoint for psychiatric treatments and rehabilitation. (Ramon, Healy & Renouf, 2007; President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003).

Importantly, recovery is increasingly conceptualized as not merely the remission of symptoms or achievement of psychosocial milestones. It is also seen as involving positive changes in how persons think about and experience themselves as individual human beings in the world, changes which may occur regardless of whether persons experience other gains in symptoms or function.(Davidson, 2003; Resnick, Rosenheck, & Lehman, 2004; Silverstein & Bellack, 2008). SAMHSA (2005) has suggested a definition of recovery as involving ten fundamental characteristics, which are that it is self-directed, individualized, associated with an increasing sense of empowerment, holistic, non-linear, associated with an approach to treatment and life that is strengths-based, associated with respect for self and facilitated by respect for the person by mental health professionals, associated with an increase in responsibility for one’s life choices, and hope.

In this sense recovery can involve persons coming to see themselves as reclaiming the sense that they possess intrinsic human value and are competent and capable of realistically affecting their lives. It may involve the development of both positive beliefs about the self and also the adoption of a fuller sense of self in place of the experience of one’s identity as having been diminished or irreparably shattered (Atwood, Orange, Stolorow, 2002; Horowitz, 2006; Laithwaite & Gumley, 2007; Seikkula, Alakare & Aaltonen, 2001; Roe, 2005). Growth in this domain has been suggested as both meaningful on its own and also instrumental in the process of persons coming to think of themselves as able to attain other recovery goals, such as forming deeper bonds with others and returning to work or school (Lysaker & Lysaker, 2008). As a matter of intuition, for example, if I develop a new sense of myself as capable, it is likely I may be willing to take more appropriate risks and persist whereas previously I might not in the face of unexpected challenges, increasing my chances of achieving healthier levels of function in a range of different domains.

Findings that a significant percentage of people with diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum disorders are capable of recapturing a richer sense of who they are suggests that it is a good time to reconsider the role of psychotherapy as a potentially helpful treatment option. Of note, we are not referring here to an interest in resurrecting a psychotherapy that looks for the roots of schizophrenia in psychological conflict or one that would urge persons to accept a very limited set of possibilities for their life. We are instead wondering whether a psychotherapy which helps recovering persons cultivate a richer and more positive self-experience across a range of dimensions closely linked to the SAMHSA principles of recovery (e.g. rejection of stigma, development of a sense of agency, responsibility, hope, empowerment and an evolving personal history) might uniquely contribute to their achieving a more satisfying life. Psychotherapy has been suggested to help a wide range of people without psychosis to develop both a richer sense of self and a more adaptive self-concept (Hermans & Dimaggio, 2005). Beyond that, others who have successfully delivered cognitive behavioral treatments focused on the symptoms of schizophrenia have also noted the benefits of moving from symptom-focused to person-focused treatments that attend to the subjective development of the sense of self. (Chadwick, 2006; Chadwick, Birchwood & Trower; 1996). Other developments in the psychotherapy of schizophrenia have also pointed to the possibility of an enriched sense of self which may emerge from integrative psychotherapy over time (Lysaker, Buck & Ringer; 2007). Treatments such as these, or further refinements of them, could be conceptualized not as “the” intervention but as nested among other interventions that assist with symptom control and reduction, skill acquisition, community integration, vocational and educational progress, etc.

Many psychosocial interventions have been demonstrated to improve outcomes in schizophrenia and other serious psychiatric illnesses, including social skills training (Kurtz & Mueser, 2008), family psychoeducation (Glynn, Cohen, Dixon & Niv, 2006), and illness management and recovery (Mueser et. al., 2002). While these interventions can provide substantial benefits, they tend to focus on improvements in specific functional outcomes, and, as typically implemented, do not allow extensive time for self-reflection or exploration. Individual psychotherapy, an activity wherein a client and therapist develop an alliance and mutual goals while using clients' guided self-exploration in the service of improving functioning and reducing distress, is at present notably absent from most discussions of recovery focused treatments, however. Though still commonly offered in a range of programs (Walkup, Wei, Sambamoorthi, Crystal, Yanos, 2006), it often takes the form of supportive therapy, without a recovery-oriented focus on the quality of the internal experience of the person and an enrichment of their sense of self. Therefore, our goal in this paper is to promote a dialogue about the possible role of psychotherapy in a comprehensive recovery-oriented treatment program.

The following discussion accordingly is divided into three sections. In the first we discuss literature on the general effectiveness of psychotherapy for persons with schizophrenia as well as comment on some of the historical factors which have previously served as a barrier to considering psychotherapy as one component among many treatments. Next we focus on the conceptual bases for thinking that psychotherapy could play a key role in promoting aspects of recovery. Here we describe two different paths by which psychotherapy might modify self-experience: 1) addressing impoverished or maladaptive personal narrative and 2) enhancing the capacity for metacognition or thinking about thinking. In the final section we discuss the needs for future research including the manualization and assessment of emerging practices, and the consideration of how current evidence- and skill-based treatments may contain key elements which could be considered psychotherapeutic.

Research on psychotherapy of schizophrenia

One of the first clinicians to advocate for individual psychotherapy for people with schizophrenia was Carl Jung (1907/1960), who treated many hospitalized patients at the Burghölzli Hospital in the early part of the 20th century. Jung noted that many people with schizophrenia are amenable to therapy, but that caution must be used because under certain conditions, therapy could cause an increase in symptoms (Jung, 1907/1960; Jung 1939/1960; Jung, 1958). In an analysis of an early case, Jung described how “the patient describes for us, in her symptoms, the hopes and disappointments of her life” (1907/1960). This statement demonstrates Jung’s view that symptoms, even bizarre ones, are linked to the life history and self-concept of the patient, and that much of the work of therapy involves increasing psychological understanding and redefining the self-concept. Once Jung left the Burghölzli, however, he rarely treated people with schizophrenia, and with a few notable exceptions (Fierz, 1991; Perry, 2005), this was true of his followers as well. Moreover, with the growth of psychoanalysis, and Freud’s (1957) claim that persons with schizophrenia could not benefit from psychoanalysis due an inability on their part to form deep attachments with others, psychotherapy for schizophrenia was virtually nonexistent by the middle of the 20th century.

Around that time, however, psychoanalysts such as Fromm-Reichmann (1954), Searles (1965), Sullivan (1962) and Knight (1946) all contended that meaningful intimate bonds with persons with schizophrenia emerged in therapy, and that those bonds could be the basis of a movement towards health. Each of these authors produced a wealth of anecdotal reports suggesting that persons with schizophrenia could use psychoanalytic psychotherapy to consider their lives and develop richer and more satisfying experiences of themselves in daily life. Despite this early enthusiasm, as reviewed in a range of sources, controlled trials failed to find significant benefits for psychoanalytic psychotherapy (Drake & Sederer, 1986). One of the key studies, referred to as the Boston Psychotherapy Study, randomly assigned over 160 adults with schizophrenia to receive exploratory insight oriented therapy or a reality based supportive psychotherapy (Gunderson et. al., 1984). Despite extensive training of therapists, methodological sophistication, and careful selection of an appropriate sample, results revealed a drop rate of just over 40% at six months and a drop rate of nearly 70% at two years, in addition to little therapeutic benefit from insight-oriented therapy. A later reanalysis of the data suggested some improvements in negative symptoms among participants assigned to the more skilled therapists (Glass et. al., 1989).

Beyond the finding which suggests two in five persons with schizophrenia are not interested in psychotherapy, at least in the forms offered in the Boston study, evolving scientific research dealt an even more fatal blow to psychotherapy around this same point in time. Empirical research failed to support the etiological theories that were the basis for psychoanalytic psychotherapy of schizophrenia. While some were claiming that psychotherapy alone was the way to address the faulty family dynamics that purportedly caused psychosis (Karon & Van Denbos, 1981), research indicated that schizophrenia was instead a genetically-influenced, neurobiological brain disorder which involves the distortion of basic human experience, and that its etiology was unrelated to unhealthy family dynamics. Nevertheless, at roughly the same time that psychotherapy seemed to be disappearing from the research horizon, surveys of mentally ill persons and their families indicated 60% were interested in psychotherapy, a rate that possibly echoes the finding that three in five remained in the Boston study at six months (Coursey, Keller & Farrell, 1995; Hatfield, Gearon & Coursey, 1996).

Since then, there has been a renewal of interest in psychotherapy for schizophrenia. This has taken several forms. For example, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), targeting psychotic and/or negative symptoms has grown significantly in the past 15 years (Pilling et. al., 2002; Rector & Beck, 2002). Originally created to address depression, the use of CBT has steadily expanded to address schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (Rector & Beck, 2002). A number of controlled trials have shown that persons with schizophrenia are willing to attend CBT and that CBT can reduce dysfunctional cognitions, leading to reductions in positive and negative symptoms, including in samples of persons resistant to medication and persons early in illness (Drury, Birchwood, Cochrane & MacMillian, 1996; Sensky et. al., 2000; Gumley et. al., 2003). More recently CBT procedures have been adapted and linked to improvements in vocational function as well (Lysaker, Davis, Bryson & Bell, in press).

Chadwick (2006) developed Person-Based Cognitive Therapy (PBCT) for distressing psychosis, in an effort to move from a symptom-focused to a person-focused therapy. PBCT integrates cognitive theory and therapy, mindfulness, Rogerian principles, and a Vygotskian social-developmental perspective which stresses language as a socially available tool which persons use to make meaning of daily activity. This approach uses cognitive and experiential techniques for working with negative self schemata and developing positive self schemata, and for promoting self-acceptance and metacognition.

Interest has also increased in using a modified form of psychoanalytic therapy for people with schizophrenia. As discussed by Bachmann et al. (2003), proposed treatment approaches vary somewhat, but all seem to agree on the following principles: 1) psychotherapy with people with schizophrenia is possible; 2) the classic psychoanalytic approach, including free association and lying on the couch with the therapist out of sight, is contraindicated; 3) the present should be emphasized over the past; 4) interpretations should only be used with caution; 5) goals of therapy should include fostering the experience of the self and the therapist as two separate people that share a relationship, stabilization of ego boundaries and identity, and the integration of the psychotic experience; 6) the frequency of sessions should range between 1–3 sessions a week and therapy should last for at least two years; and 7) therapists who work with people with schizophrenia need to have a high level of frustration tolerance, and not have a need to derive narcissistic gratification from the patient’s effort or progress. Some evidence suggests that such an approach can be helpful, at least for people who are more clinically stable at the outset of treatment (Hauff et al., 2002).

Finally, Rosenbaum and colleagues (2005) have reported the results of a large scale study in Denmark of over 560 first episode patients who received treatment as usual, supportive individual psychodynamic psychotherapy or an integrated, assertive, psychosocial and psychoeducation treatment. Results reported thus far suggest that both the integrated psychosocial treatment and the supportive psychodynamic psychotherapy may lead to better overall functional outcomes after one year of treatment.

Perhaps even more compelling than these data and suggestions, however, is that recent theoretical developments suggest new methods and mechanisms by which psychotherapy for schizophrenia might be effective. These are discussed in the section below.

A conceptual basis for a recovery oriented psychotherapy focused on self-experience in schizophrenia

Two decades ago, Coursey (1989) pointed out that a key challenge for any psychotherapy of schizophrenia is the development of a treatment rationale that is consistent with the evolving conceptualization of the roots of the disorder. More recently, Freeman et al. (2004) noted that attempts to modify delusions must include a rationale that makes sense to the patient in terms of his/her life experience. One example of success in these regards is the claim of CBT that the neurobiological processes of schizophrenia may lead to tenaciously held delusional beliefs. Neurobiological factors are seen in this view as interacting with social, developmental and psychological factors resulting in maladaptive beliefs about the self, and tendencies to attribute intentions to others that are rigid and overly negative. CBT helps to correct those beliefs through a systematic, collaborative process of belief examination and prediction of the consequences of behaviors and events, leading to improvements in quality of life.

Following this model we would suggest that psychotherapy could be conceptualized more broadly as helping persons to recover richer experiences of themselves as human beings in the world. But if psychotherapy were to intervene here and help address issues related to self-experience, what processes would be implicated? Certainly some forms of psychoanalysis have suggested that they may uniquely promote the growth of richer or fuller self activity. These though have tended to propose that psychoanalysis leads to enriched self experience by strengthening defenses or resolving conflicts which caused psychosis in the first place (Karon, 2003), a possibility that seems incompatible with contemporary views on the etiologies of schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms. In response we argue that an integrative psychotherapy could be conceptualized as assisting persons to recover a richer self experience, one that could be understood and accepted by others, following two different paths.

Psychotherapy and narrative

First, psychotherapy in schizophrenia could address impoverished personal narrative. Consistent with the SAMHSA principles of recovery including self-direction, empowerment, individualized and holistic approaches and hope, psychotherapy could be seen as a forum for the reconstruction of personal narrative in an interactive fashion involving the labeling of old and new behaviors as being consistent with a positive, gradual, growth process in which the self is viewed as both more multifaceted and more integrated (Silverstein, Spaulding, & Menditto, 2006). As described by Lysaker and Lysaker (2008) and others (Bradfield & Knight, 2008; Meehan & MacLachlan, 2008), qualitative analyses have suggested that experiences of diminished subjectivity in schizophrenia may reflect in part disruptions in the dialogical processes by which persons carry out conversations with one another and themselves. In particular it has been suggested that if the structures which sustain these conversations fail, there may be a loss of evolving self-experience, which in turn could lead persons to regard themselves as diminished or on the verge of destruction in at least three different ways. First, ongoing dialogue may relatively cease, resulting in the experience of the self as barren or empty. In such experiences the person’s own life story may be grossly undeveloped and unembellished, consisting of only a few fragmented potential internal states which are without meaningful links to life events. Second, dialogue may persist but be dominated by a few inflexible views leading to a monological or repetitive life-narrative. Finally, it is possible that dialogue will continue but be completely disorganized to the point of near cacophony. In such a condition, the potential for coherent narrative is lost, and replaced by a rapid and chaotic succession of self-experiences, which leads to an incoherent life-narrative filled with abstract generalizations and preoccupations that appear to be divorced from consensually accepted accounts of reality.

Regardless of how impoverished narratives are described or categorized, there are a number of interpersonal and biological factors that have been associated with schizophrenia which could play a role in their development (Roe, 2005; Lysaker & Buck, 2008). Considering interpersonal issues first, certainly one factor that might impact personal narrative in schizophrenia is socially prevalent stereotypes of mental illness which cast persons with mental illness as incompetent or dangerous (Swindle, Heller, Pescosolido & Kikuzawa, 2000). These may result in self-stigma, which is reflected in personal narratives of oneself as helpless or damaged (Lysaker, Roe & Yanos, 2007). If the world sees one as helpless and incapable, persons might well see themselves as not worthy of a story being told or may not dare to adopt a personal story which portrays them so poorly. Schizophrenia in this way may disrupt a person’s sense of autobiography (Lysaker & Buck, 2007) just as do many other serious medical illnesses (Bury, 1982). It is important to note here that this process can start well before the initial diagnosis of schizophrenia, which is typically in late adolescence or early adulthood. Many people with schizophrenia have a history of poor premorbid social and cognitive functioning (Neumann, Grimes, Walker & Baum, 1995; Schenkel & Silverstein, 2004) dating back to childhood or adolescence. These can serve as rate limiting factors for a healthy self-concept, as well as triggers of negative responses from others which can in turn facilitate a negative and stigma-centered self concept.

Turning to more biologically oriented issues, impairments in neurocognition (Horotitz, 2006; Bell, Tsang, Greig & Bryson, 2007; Uhlhaas & Mishara, 2007; Uhlhass & Silverstein, 2005) have also been suggested to make it difficult for persons with severe mental illness to organize complex subjective experiences in a coherent manner. Moreover, schizophrenia has been associated with reduced levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; Piridldar, Gönül, Taneli & Akdeniz, 2004), resulting in reductions in neurogenesis, and reduced opportunities to form new neuronal connections based on new experiences. Although the reason for the BDNF reduction is not clear, it is likely due in part to physical inactivity and to under-stimulating environments (Osborn, Nazareth & King, 2007; Cohen & Sokolovsky, 1978) and findings that BDNF levels and neurogenesis can be increased via physical activity and/or cognitive stimulation (Dishman et al., 2006; Ratey, 2008; Vinogradov et al., 2007). Other correlates of schizophrenia, such as obesity, substance abuse, homelessness, poor diet, metabolic abnormalities, and cardiovascular disease (Osborn, Nazareth & King, 2007), can also contribute to poor brain health, and, therefore, to a reduction in the cognitive flexibility required for the ongoing construction of a personal narrative.

Finally, trauma, which involves both biological and interpersonal factors, may also play a role in impoverished narrative in schizophrenia. A range of studies suggest a high rate of trauma in the histories of people with schizophrenia (Read, Van Os, Morrison & Ross, 2005; Van Zelst, 2008; Schenkel, DiLillo, Spaulding & Silverstein, 2005) which could affect self-experience in several ways. For example, many traumatized people are unable to access or describe their own emotional experience over time (Frewen et al., 2008). In addition, the chronically high stress level associated with trauma histories can narrow the range of interpretations of experience that are considered, and lead to dysregulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in neuronal death in the hippocampus, thereby reducing the ability to experience memories in their proper context (Read, Van Os, Morrison & Ross, 2005; Van Winkel, Stefanis, Myin-Germeys; 2008). Consistent with the power of self-narrative presented above, the most empirically validated treatments for traumatization in non-psychotic populations, prolonged exposure (Foa et al., 1999) and cognitive processing therapy (Resick & Schnicke, 1992), incorporate development of a coherent narrative of the traumatic event as a core component of the healing process. With regards to schizophrenia, CBT focused on cognitive restructuring has been found to be effective (Frueh et al., 2004), presumably also because of modifications in self-statements, and ultimately, personal narrative.

With this backdrop, psychotherapy could be conceptualized as an opportunity to dismiss or deepen a previously held life story that was maladaptive as a result of any of a broad range of biological and interpersonal factors. Beyond exploring the validity of a particular conclusion or response to a particular symptom, psychotherapy could, as it does for many others (Mishara, 1995; Adler, Skalina & McAdams, 2008), represent a place where persons first recognize and then examine the core beliefs they have told to, or accepted about, themselves. For instance, rather than focusing on a specific hallucinations, a discussion of one’s larger life might, in keeping with the SAMHSA principle that suggests recovery is a holistic process, lead persons with schizophrenia to develop richer and more layered stories about who they are in the present, who they have been across the course of their life and what possibilities life possesses for them. In line with the SAMSA principles of recovery, a deepened personal narrative might then naturally be an opportunity for experience of oneself as an active agent who prevails in the face of adversity. Again whereas symptom or problem focused approaches might help persons move past specific hurdles, a more narrative approach might help a person evolve a larger understandings of him/herself which might generalize to a range of situations. Providing some pilot data on this possibility, to date, at least two quantitative case studies of people with schizophrenia have suggested that improvements in the richness of personal narratives may result during the course of individual psychotherapy and that improvements are linked with changes in symptoms and other assessments of the ability to make sense of daily experience (Lysaker et al., 2005; Lysaker et al., 2007). Other studies have suggested that self concept is a meaningful predictor of outcome in a range of other domains in both first episode (Harder, 2006) and more advanced phases of illness, again regardless of the etiology of difficulties with narratization (Lysaker et al., 2006).

Psychotherapy and metacognition

A second way psychotherapy might address impoverished self experience is through assisting persons with schizophrenia to develop enhanced capacities for metacognition. Metacognition refers to the ability to think about thinking, a capacity which clearly is a precondition for the ability to tell a coherent and reflective story about oneself in the world. Of note, it shares a considerable amount in common with terms such as “mindreading,” (Dimaggio et al., 2008) “theory of mind,” (Brune, 2005) and “mentalizing” (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist & Target, 2002) all of which refer to a person’s general capacity to think about thinking. We therefore consider it an umbrella term that describes a wide range of internal and socially driven cognitive acts which contain primarily reflexive qualities (Semerari et al., 2003).

Deficits in metacognition have been widely observed in schizophrenia and include difficulties apprehending one's own thoughts and feelings and the thoughts and feelings of others. These deficits are closely linked to psychosocial dysfunction and are not reducible to symptoms or other aspects of psychopathology (Brune, 2005; Franck et al., 2001; McGlade et al., 2008; Stratta et al., 2007). Not surprisingly decrements in metacognition have been linked to impoverished self-experience (Corcoran & Frith, 2003; Lysaker et al., 2008). Indeed, if it is difficult to recognize one's own thoughts and intentions it should be difficult to experience oneself as an agent or unique being in the world. As in the case of impoverished narratives, deficits in metacognition are likely the result of numerous factors including reductions in neurocognitive capacity as noted above (McGlade et al., 2008; Lysaker et al., 2007; Schenkel, Spaulding, Silverstein, 2005), as well as trauma and difficulties with managing painful affects or regulating emotional states (Read, Van Os, Morrison & Ross, 2005; Lake, 2007; MacBeth & Gumley, 2008; St-Hilaire, Cohen & Docherty, 2008).

Can psychotherapy improve metacognitive skills? As noted by Choi-Kain and Gunderson, (2008) a number of forms of psychotherapy exist which focus on promoting metacognitive capacity in persons with mental disorders generally less severe than schizophrenia. Most prominently, Fonagy and colleagues (2002) developed a psychotherapy that seeks to enhance the ability to think about mental states. Originally designed to target persons with borderline personality disorder, results of a randomized clinical trial revealed that this treatment increased metacognition (referred to as mentalization) and resulted in reductions in distress, suicide attempts and levels of dysfunction when assessed at the conclusion of the trial, at 18 months follow-up, and five years later, when compared with treatment as usual (Bateman & Fonegy, 2001; Bateman & Fonegy, 2008).

While these procedures were rooted in the psychoanalytic tradition, others have similarly linked improvements in metacognition with increases in health and wellness in psychotherapy. One group, working from within a cognitive perspective, has found that growth in metacognitive capacity across the course of psychotherapy was linked with improved function in a wide range of personality disorders (Dimmagio et al., 2007; Fiore et al., 2008). Investigators examining other Axis I disorders including anxiety, depression, substance abuse and eating disorders have similarly reported findings that participation in psychotherapy was associated with improvements in metacognition and reductions in psychopathology (Karlsson & Kermott, 2006; Moreira, Beutler & Goncalves, 2008; Osakuke et al., 2007; Scarderude, 2007).

In schizophrenia, several lines of evidence suggest that it is possible to improve metacognitive skills. For example, Spaulding et al (1999) in a study of cognitive rehabilitation, demonstrated that the primary gains involved not improvements in specific aspects of basic cognition, but rather, an increased ability to utilize the cognitive process that is most relevant to solve the task at hand. Regarding social cognition, a new intervention, Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) has shown promise in improving emotion perception and theory of mind, and reducing hostile attributions regarding others in people with schizophrenia (Penn, Roberts, Combs & Sterne, 2007). Furthermore, many versions of CBT for psychosis (Kingdon & Turkington, 2004) incorporate explicit discussions of common errors in logic, and procedures to correct these misperceptions as a core aspect of the treatment.

In light of this literature it seems possible that some of these procedures could be modified for an integrated psychotherapy for schizophrenia. In particular, if metacognition is thought of as a capability that varies along a continuum from good to limited, psychotherapy could be conceptualized as aiding in the recovery of metacognitive capacity by providing a place in which such capacities can be practiced and exercised at increasing degrees of complexity. Psychotherapy can offer clients a chance, in the manner of physical therapy, to develop over time the capacity to re-engage in acts they were once better able to perform. With such practice, metacognitive capacities that have atrophied may be improved such that more complex metacognitive acts can be performed with greater ease in regular life, leading to a genuinely greater sense of empowerment and self confidence. Following the metaphor of physical therapy, practicing of these capacities may be difficult and painful, but incremental progress is to be expected given the plasticity of the human organism.

Consistent with this, Chadwick (2006) has noted that the goals of PBCT include promoting metacognitive insight with regards to the meaning of symptoms, relationship to internal experiences, negative self-schemata, and the self as a complex, contradictory, and changing process. He provides methods for achieving these goals, and sample therapy transcripts documenting how this work proceeds. Also consistent with this, two quantitative case studies of people with schizophrenia have suggested that improvements in metacognition may occur across individual psychotherapy and that improvements are linked with changes in other forms of assessment (Lysaker, Buck & Ringer, 2007; Lysaker et al., 2005).

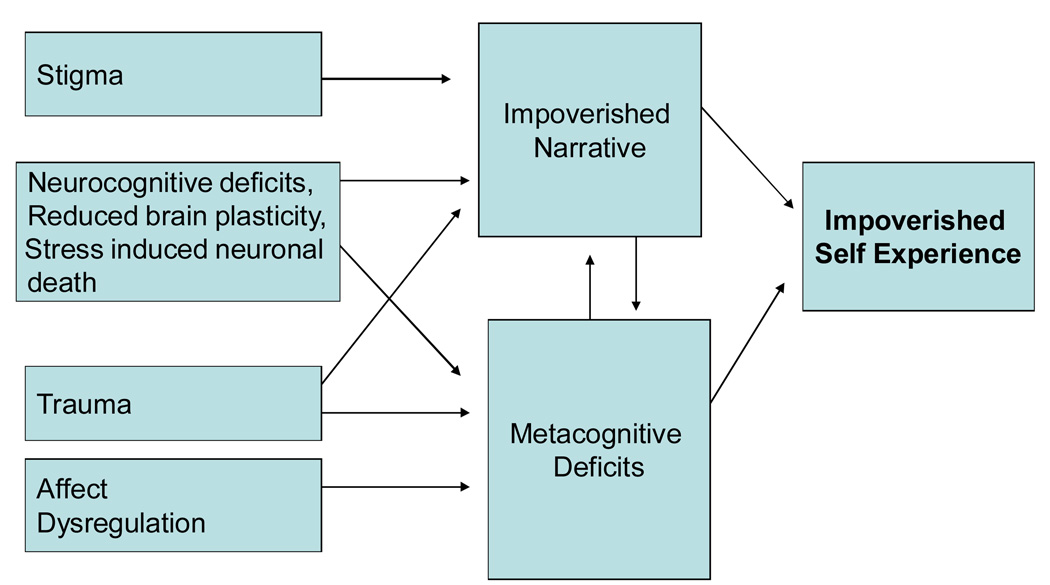

As summarized in Figure 1, we thus propose two paths to impoverished self experience which offer a target or focus for psychotherapy concerned with subjective elements of recovery. Stigma, several forms of neurocognitive compromise and trauma may lead to impoverished narratives, while the same forms of neurocognitive compromise, trauma and affect dysregulation may lead to metacognitive deficits. The deficits in metacognition and impoverished narratives could then be seen directly as leading to alterations in self-experience.

Figure 1.

Two paths to impoverished self-experience

Future research: Three related foci

Given the potential of psychotherapy to address subjective aspects of recovery by addressing both personal narrative and metacognitive capacity, one clear need for future research is the development of manualized treatments which could be tested for feasibility and effectiveness in randomized controlled trials. Following the illustration in Figure 1, we envision this psychotherapy as addressing both narrative and metacognition deficits, conceptualizing them as interdependent. Without metacognitive capacity it should be difficult to evolve a complex storied understanding of one’s life, and without a sense that one’s life is worth telling a story about there should be little need for complex acts of metacognition. With regards to issues of narrative we would also envision this psychotherapy as addressing developing narratives as complex multilayered acts. The development of an enriched narrative for one person might not proceed in the same manner as for another, but in general this work should involve the simultaneous development of a number of semi-independent stories, including for instance, stories about personal challenges, aspects of life where competence was experienced, grief over losses, hopes for the future, and stories about how the present situation could evolve into the hoped-for future. Challenges and symptoms would need to be linked to personal life experience in a way that was both potentially consensually valid but also preserving of self-esteem, rather than attributing them exclusively to a biological illness and brain disorder.

Turning to the issue of metacognition, we would envision a psychotherapy that might promote recovery by providing a place in which clients may develop their capacities to think about thinking. This might well involve offering opportunities to practice acts of metacognition leading to the strengthening of the ability to perform metacognitive acts of increasing complexity. As discussed by Chadwick (2006), psychotherapy can provide many opportunities for this, in terms of examining and monitoring: 1) attributions regarding self and others; 2) symptoms and mental states; 3) schemata-linked habitual reaction patterns in thinking and behavior; and 4) thoughts and feelings about all parts of the self. And, as suggested by Buck and Lysaker (in press) psychotherapy is thus one method in which different kinds of metacognition capacity are regularly assessed and intervention is accordingly staged to match client’s capacities.

The development and definition of such treatments would seem likely to be able to draw from a range of existing procedures and by definition be integrative in nature. For instance, cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis has been used to address the personal meaning of symptoms (Silverstein, 2007) as well as awareness of the process of thinking beyond the correction of maladaptive beliefs (Davis & Lysaker, 2005). The incorporation of methodologies which target metacognition in other groups (Bateman & Fonegy, 2001; Fiore et al. 2008) could also enrich and speed the process of definition and testing of such an intervention.

A related issue for future research regards the development of tools that could be used to assess changes in subjective sense of self. If psychotherapy can lead to change in personal narrative or metacognition how could this be reliably assessed? Certainly a range of relevant instruments exist, Resnick and colleagues (2004), for instance, have reported on the responses of over 800 persons to measures of life satisfaction, hope, knowledge about mental illness and empowerment and linked those with other aspects of outcome. Others have similarly linked other assessment of hope and internalized stigma to outcome as well (Wright, Gronfein & Owens, 2000; Landeen, Seeman, Goering & Streiner, 2007).

While these measures may produce estimates of beliefs relevant to self-experience, other efforts have also recently been undertaken to develop a recovery oriented scale to quantitatively assess self-experience as it is expressed in the personal narratives of persons with schizophrenia. One tool, the Scale to Assess Narrative Coherence (STAND; Lysaker et al., 2006), can be used to rate the extent to which a coherent story of an individual person and their psychiatric challenges is present in spontaneously generated speech samples (e.g. from psychotherapy transcripts or semi-structured interviews). The STAND assesses specifically the extent to which persons portray themselves as possessing social worth, being connected to others, and having the ability to meaningfully affect their own destiny, elements closely tied to the SAMHSA principles of recovery. Evidence of inter-rater reliability, internal consistency and concurrent validity have been demonstrated across several samples of adults with schizophrenia in a post- acute phase of illness (Lysaker, Buck, Taylor & Roe, 2008; Lysaker et al., 2006). Davidson (2003) noted that the earliest phases of recovery may involve struggling to fully accept oneself as a person whose story is worthy of being told. Roe and colleagues note that the later stages of recovery involve achieving mastery in the process of constructing and negotiating meaning (2006). The STAND may offer developing research on recovery oriented psychotherapy as a way to quantify movement along this most personal and subjective continuum.

Regarding assessment of metacognition, formal tests exist which assess different aspects of metacognition (Brune, 2005). However, these instruments assess metacognition as cued within the laboratory, and were not developed to detect metacognitive capacity in speech samples such as those derived from psychotherapy sessions and clinical interviews (Lysaker et al., 2008). As a result, paralleling the issue of narrative, efforts have also been undertaken to develop a scale that could rate the presence of metacognitive capacity from the same speech samples utilized to rate the STAND (e.g. from psychotherapy transcripts or semi-structured interviews). This scale, the Metacognition Assessment Scale (MAS; Semerari et al., 2003) was originally designed to detect changes within psychotherapy transcripts in the ability of persons with severe personality disorders to think about their own thinking, and has since been modified for use as a dimensional scale. The MAS contains four scales which pertain to different foci of metacognitive acts: 1) the comprehension of one’s own mental states, 2) the comprehension of other individuals’ mental states, 3) the ability to see the world as existing with others having independent motives, and 4) the ability to work through one’s representations and mental states to implement effective action strategies in order to accomplish cognitive tasks or cope with problematic mental states. Individuals are assumed to possess varying capacities in each of these domains such that any given persons might be able to achieve more or less complex metacognitive acts in each of these scales.

Evidence of inter-rater reliability and validity of the MAS have been presented across several samples of adults with schizophrenia in a post acute phase of illness (Lysaker et al., 2007; Lysaker et al., 2008) as well as evidence that it measures different phenomena than does the STAND (Lysaker, Buck, Taylor & Roe, 2008). Like the STAND, the MAS may offer future research on recovery-oriented psychotherapy a way to quantify movement along this most personal and subjective continuum.

Importantly, with the development of assessments of changes in narrative and metacognition, opportunities for other important practical and more theoretical avenues of research are likely to open. First, with future general empirical support for these procedures it will have to be determined what would assist clinical settings to implement such a form of psychotherapy. While SAMHSA and others frame recovery as a non-linear and certainly not necessarily a relatively short term process, what are the sorts of time frames within which change might be expected? Another set of practical issues to be addressed will also pertain to what forms of training and supervision are necessary to support them. For instance, what sorts of staff can learn and implement these procedures, and what staff and environmental variables determine whether the intervention is implemented faithfully?

Second, on a more theoretical note, while we have focused on self-experience as a meaningful domain of recovery in its own right, changes in this domain are likely to lead to changes in other domains of recovery. With new procedures and assessments of changes in self-experience, it may be possible to empirically examine the kinds of reciprocal relationships that exist between changes in the capacities for metacognition and the richness personal narrative with changes in functional assessments of work, interpersonal and community function. Such research would not only be of theoretical import in terms of conceptualizing the process of recovery but also to might help to develop and refine new treatments. Ultimately, such a program of research could be capable of exploring whether the kinds of psychotherapy described above have an effect on more internal and subjective constructs linked to recovery such as the extent to which one feels one is more in control of one’s choices, self-esteem, involvement in one's own recovery process, and feeling that one's life has meaning.

Consistent with this, as has been long noted, participation in a range of rehabilitative activities may reshape how one makes meaning of one’s life both in the immediate and larger narrative sense (Bell, Tsang, Greig & Bryson, 2007; Harris et al., 1997). Thus it seems important to study the psychotherapeutic effects of currently employed rehabilitative and other evidence-based methods which stress the benefits of natural supports. Does the acquisition of skills and the development of natural supports in other evidenced based programs have similar or different effects on personal narrative, cognition and social skills as psychotherapy? Such research may point to a way to further enhance the effects of these interventions with regard to narrative and metacognition. It may also point to important developments with regards to the interface of psychotherapy and other interventions and some promising avenues for synergistic combinations of interventions. For example, might not cognitive rehabilitation (to improve cognitive flexibility), for instance augment the possible impact of a recovery oriented psychotherapy leading to greater degree of improvement in the subjective domains of recovery? Similarly, given findings on the multiple positive effects and meanings of work for people with schizophrenia, might not supported employment help generate beliefs and feelings about the self that can be further explored and integrated with other aspects of personal narrative in psychotherapy (Roe, 2001; Cook et al., 2005)?

Finally, future research is also needed to address for whom such forms of psychotherapy might be most useful. For instance are these interventions better suited for persons who are earlier vs. later on in their illness? Intuitively, given that persons early in the their illness have many difficult things to make sense of (i.e., the meaning of the psychotic episode in their life trajectory, whether it is an obstacle to overcome or evidence of inevitable decline, whether life dreams will be pursued or abandoned, etc.), and many troublesome decisions to reach, a therapy that addressed issues of narrative and metacognition might be uniquely useful. Of note, as suggested in one recent review, the usefulness of more symptom focused cognitive interventions is still a matter of debate (Morrison, 2009). That said, it may also be that persons late in their illness may also have unique though somewhat different needs, including the mourning of dreams lost earlier in life due to illness as well as just the ravages of persistent disease and what is seen as possible for the remainder of life. Research has suggested the needs of older persons with schizophrenia are still not well understood and often go unaddressed (Karlin, Duffy, & Gleaves, 2008).

Summary and conclusions

Recent changes in the conceptualization of recovery have pointed to the possibility that psychotherapy could again come to play a significant role in the treatment of persons with schizophrenia. To explore this issue we have summarized literature on the history of psychotherapy for schizophrenia and discussed whether impoverished self experience in schizophrenia, a potent barrier to recovery, could be targeted by psychotherapy. In particular we have suggested psychotherapy could address two interrelated facets of self experience personal narrative and the capacity for metacognition and potentially set the stage for the achievement of an enhanced the quality-of-life. We have suggested that with the attainment of a richer personal narrative and greater capacity to think about thinking, individuals with schizophrenia may feel sufficiently empowered and able to envision a realistically hopeful future, and to plan out courses of action likely to lead to goal attainment. With a fuller multi-dimensional and storied account of one’s own strengths and weaknesses, and with a greater ability to reason about one’s own internal states, it seems likely that persons could make more reasoned and less impulsive decisions in the face of adversity. In contrast to symptom or problem focused approaches, addressing these larger facets of self-experience might enable persons to flexibly formulate more courses of action in response to a greater range of challenges and to weather general threats to self-esteem, all leading to sustained wellness and the experience on the part of the persons with schizophrenia that they themselves are shaping a meaningful life for themselves in an individualized, self-determined and holistic manner.

Regarding future research we have suggested that these possibilities point to the need to develop carefully defined and testable integrative psychotherapeutic methods, tools for tracking change in self experience over time and explorations of the potential psychotherapeutic impact of existing rehabilitative practices and the synergistic combination of psychotherapy with other practices.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ser.

Contributor Information

Paul H Lysaker, Roudebush VA Medical Center and the Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana

Shirley M. Glynn, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System at West Los Angeles, Univeristy of California Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles CA

Sandra M. Wilkniss, Thresholds Institute, Chicago, IL

Steven M. Silverstein, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey – University Behavioral HealthCare and Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ

References

- Adler JM, Skalina LM, McAdams DP. The narrative reconstruction of psychotherapy and psychological health. Psychotherapy Research, Sep. 2008;12:1–16. doi: 10.1080/10503300802326020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood GE, Orange DM, Stolorow RD. Shattered Worlds/Psychotic States. A Post-Cartesian View of the Experience of Personal Annihilation. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2002;19:281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann S, Resch F, Mundt C. Psychological treatment for psychosis: history and overview. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. 2003;31:155–176. doi: 10.1521/jaap.31.1.155.21930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonegy P. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: An 18 month follow up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:36–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonegy P. 8 year follow up of patient treated for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:631–638. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Tsang HW, Greig T, Bryson GJ. Cognitive predictors of symptom change for participants in vocational rehabilitation. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;96:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS. Scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: Concordance, contrasts and implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:432–442. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck KD, Lysaker PH. Addressing metacognitive capacity in the psychotherapy for schizophrenia: A case study. Clinical Case Studies. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield CB, Knight ZG. Intersubjectivity and the schizophrenic experience: A hermeneutic phenomenological exploration. South African Journal of Psychology. 2008;38(1):33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brune M. Theory of mind in schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:21–42. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury MU. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Social Health & Illness. 1982;4:167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick P. Person-based cognitive therapy for distressing psychosis. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick P, Birchwood, Trower . Cognitive therapy for delusions, voices and paranoia Oxford. England: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Choi-Kain LW, Gunderson JG. Mentalization: Ontogeny, assessment and pllication in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1127–1135. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CI, Sokolovsky J. Schizophrenia and social networks: ex-patients in the inner city. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1978;4:546–560. doi: 10.1093/schbul/4.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Leff HS, Blyler CR, Gold PB, Goldberg RW, Mueser KT, Toprac MG, McFarlane WR, Shafer MS, Blankertz LE, Dudek K, Razzano LA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller J. Results of a multisite randomized trial of supported employment interventions for individuals with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:505–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran R, Frith CD. Autobiographical memory and theory of mind: Evidence of a relationship in schizophrenia. Psychology Medicine. 2003;33:897–905. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursey RD, Keller AB, Farrell EW. Individual psychotherapy and persons with serious mental illness: the clients perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1995;21:283–301. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursey RD. Psychotherapy with persons suffering from schizophrenia: the need for a new agenda. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1989;15:349–353. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L. Living Outside Mental illness: Qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia. New York: New York University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davis LW, Lysaker PH. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and functional and metacognitive outcomes in schizophrenia: A single case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Dimaggio G, Lysaker PH, Carcione A, Nicolò G, Semerari A. Know yourself and you shall know the other… to a certain extent: Multiple paths of influence of self-reflection on mindreading. Consciousness and Cognition. 2008;17:778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimaggio G, Semerari A, Carcione A, Nicolò G, Procacci M. Psychotherapy of personality disorders. London: Bruner Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Berthoud H-R, Booth FW, Cotman CW, Edgerton VR, Fleshner MR. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity. 2006;14:345–356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Sederer LI. The adverse effects of intensive treatment of schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1986;27:313–326. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(86)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, MacMillian F. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: A controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169:593–601. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierz HK. Jungian Psychiatry. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag (original works published 1963 and 1982); 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore D, Dimaggio G, Nicoló G, Semerari A, Carcione A. Metacognitive interpersonal therapy in a case of obsessive-compulsive and avoidant personality disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;64:168–180. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LH, Meadows EA, Street GP. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist EL, Target M. Affect regulation, Mentalization, and the development of the self. New York: Other Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- France CM, Uhlin BD. Narrative as an outcome domain in psychosis. Pschology and Psychotherapy-Theory Research and Practice. 2006;79:53–67. doi: 10.1348/147608305X41001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck N, Farrer C, Geirgueff N, Marie-Cardine M, d’Amato T, Jeannerod M. Defective recognition of one’s own actions in patient with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:454–459. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D, Garety PA, Fowler D, Kuipers E, Bebbington PE, Dunn G. Why do people with delusions fail to choose more realistic explanations for their experiences? An empirical investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:671–680. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Neurosis and psychosis. In: Strachev A, Strachev J, translators. Collected papers. Vol. II. London, England: Hogarth Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Lanius RA, Dozois DJ, Neufeld RW, Pain C, Hopper JW, Densmore M, Stevens TK. Clinical and neural correlates of alexithymia in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;17(1):171–181. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Buckley TC, Cusack KJ, Kimble MO, Grubaugh AL, Turner SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among people with severe mental illness: A proposed treatment model. Journal of Psychiatry Practice. 2004;10:26–38. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm-Reichmann F. Psychotherapy of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1954;111:410–419. doi: 10.1176/ajp.111.6.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass LL, Katz HM, Schnitzer RD, Knapp PH, Frank AF, Gunderson JG. Psychotherapy of schizophrenia: An empirical investigation of the relationship of process to outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146(5):603–608. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, Niv N. The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunities and obstacles. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(3):451–463. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumley A, O’Grady M, McNay L, Reilly J, Power K, Norrie J. Early intervention for relapse in schizophrenia: Results of a 12-month randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(3):419–431. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Frank AF, Katz HM, Vannicelli ML, Frosch JP, Knapp PH. Effects of psychotherapy in schizophrenia: II. Comparative outcome of two forms of treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1984;10:564–598. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder S. Self-Image and Outcome in First-Episode Psychosis. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2006;13:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Bebout RR, Freeman DW, Hobbs MD, Kline JD, Miller SL, Vanasse LD. Work stories: psychological responses to work in a population of dually diagnosed adults. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1997;68(2):131–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1025453605130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Grossman LS, Jobe TH, Herbener ES. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery? A 15 year mutli-follow-up study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31(3):723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB, Gearon JS, Coursey RD. Family member’s rating of the use and value of mental health services: Results of a nation NAMI survey. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:825–831. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauff E, Varvin S, Laake P, Melle I, Vaglum P, Friis S. Inpatient psychotherapy compared with usual care for patients who have schizophrenic psychoses. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:471–473. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans HJM, Dimaggio G. The Dialogical Self in Psychotherapy. London England: Brunner-Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz R. Memory and meaning in the psychotherapy of the long term mentally ill. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2006;34:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. C. G. Jung, The psychology of dementia praecox (Volume 8, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung) Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1907/1960. The Psychology of Dementia Praecox. (original work published in 1907) [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. C.G. Jung, The Psychology of Dementia Praecox (Volume 8, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung) Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1939/1960. On the psychogenesis of schizophrenia. (original work published 1939) [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. C.G. Jung The Psychology of Dementia Praecox (Volume 8, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung) Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1958. Schizophrenia. (original work published 1958) [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Duffy M, Gleaves DH. Patterns and predictors of mental health service use and mental illness among older and younger adults in the United States. Psychological Services. 2008;5(3):275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, Kermott A. Reflective functioning during the process in brief psychotherapies. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research Practice Training. 2006;43:65–84. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karon BP. The tragedy of schizophrenia without psychotherapy. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychotherapy. 2003;31:89–118. doi: 10.1521/jaap.31.1.89.21931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive Therapy of Schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Knight RP. Psychotherapy of an adolescent catatonic schizophrenic with mutism. Psychiatry. 1946;9:323–339. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1946.11022612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(3):491–504. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laithwaite H, Gumley A. Sense of self, adaptation and recovery in patients with psychosis in a forensic NHS setting. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2007;14:302–316. [Google Scholar]

- Lake CR. Hypothesis: Grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia: Paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;43:1162–2008. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeen JL, Seeman MV, Goering P, Streiner D. Schizophrenia: Effects of perceived stigma on two dimension of recovery. Clinical Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses. 2007;1:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD. Is Recovery from Schizophrenia Possible? An Overview of Concepts, Evidence, and Clinical Implications. Primary Psychiatry. 2008a;15(6):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD. Insight and Schizophrenia: correlates, etiology and treatment. Clinical Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses. 2008b;2(2):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Taylor AC, Roe D. Associations of metacognition, self stigma and insight with qualities of self experience in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2008;157:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD. Illness and the disruption of autobiography: accounting for the complex effect of awareness in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2007;45(9):39–45. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Hammoud K, Taylor AC, Roe D. Associations of symptom remission, psychosocial function and hope with qualities of self experience in schizophrenia: Comparisons of objective and subjective indicators of recovery. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;82:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Ringer J. The recovery of metacognitive capacity in schizophrenia across thirty two months of individual psychotherapy: A case study. Psychotherapy Research. 2007;17:713–720. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Roe D. Psychotherapy and recovery in schizophrenia: A proposal of critical elements for an integrative psychotherapy attuned to narrative in schizophrenia. Psychological Services. 2007;4:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LD, Bryson GJ, Bell MD. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on work outcomes in vocational rehabilitation for participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Jones AM, Strasburger AM, Hunter NL. The interplay of relationship and technique in the long-term psychotherapy of schizophrenia: A single case study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2007;7:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LD, Eckert GJ, Strasburger A, Hunter N, Buck KD. Changes in narrative structure and content in schizophrenia in long term individual psychotherapy: A single case study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2005;12:406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G, Buck KD, Carcione A, Nicolò G. Metacognition within narratives of schizophrenia: Associations with multiple domains of neurocognition. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Lysaker JT. Schizophrenia and The Fate of the Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Taylor A, Miller A, Beattie N, Strasburger A, Davis LW. The Scale to Assess Narrative Development: Associations with other measures of self and readiness for recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194 doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000202512.54587.34. 233-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Warman DM, Dimaggio G, Procacci M, LaRocco V, Clark LK, Dike C, Nicolò G. Metacognition in prolonged schizophrenia: Associations with multiple assessments of executive function. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:384–389. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181710916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Premorbid adjustment, symptom development and quality of life in first episode psychosis: a systematic review and critical reappraisal. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;117(2):85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39:335–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlade N, Behan C, Hayden J, O’Donoghue T, Peel R, Haq F, Gill M, Corvin A, O’Callaghan E, Donohoe G. Mental state decoding v. mental state reasoning as a mediator between cognitive and social function in psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;193:77–78. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.044198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire W. The psychology of dementia praecox. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1960. Editorial note. In C. G. Jung. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan T, MacLachlan M. Self construction in schizophrenia: a discourse analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2008;81:131–142. doi: 10.1348/147608307X256777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara AL. Narrative and psychotherapy: The phenomenology of healing. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1995;49:180–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1995.49.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira P, Beutler LE, Gonçalves OF. Narrative change in psychotherapy: differences between good and bad outcome cases in cognitive, narrative, and prescriptive therapies. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;64:1181–1194. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A. Cognitive behavior therapy for first episode psychosis: Good for nothing or fit for purpose. Psychosis. 2009;1(2):103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton D, Tanzman B, Schaub A, Gingerich S. Illness management and recovery for severe mental illness: A review of the research. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1272–1284. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Raskin JD. Constructions of Disorder: Meaning-Making Frameworks for Psychotherapy. Washington DC: APA Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Grimes K, Walker EF, Baum K. Developmental pathways to schizophrenia: behavioral subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:558–566. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC. Psychotherapy Relationships that Work. NY Oxford University press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Osatuke K, Mosher JK, Goldsmith JZ, Stiles WB, Shapiro DA, Hardy GE, Barkham M. Submissive voices dominate in depression: Assimilation analysis of a helpful session. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In-Session. 2007;63:153–164. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DP, Nazareth I, King MB. Physical activity, dietary habits, and coronary heart disease risk factor knowledge amongst people with severe mental illness: A cross sectional comparative study in primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:787–793. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Roberts DL, Combs D, Sterne A. Best practices: The development of the Social Cognition and Interaction Training program for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:449–451. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JW. The far side of madness. 2nd ed. Putnam, CT: Spring Publications (first edition published 1974); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, Garety P, Geddes J, Orbach G, Morgan C. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(5):763–782. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirildar S, Gönül AS, Taneli F, Akdeniz F. Low serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with schizophrenia do not elevate after antipsychotic treatment. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacoly and Biological Psychiatry. 2004;28:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. Final Report. 11. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03–3832. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon S, Healy B, Renouf N. Recovery from mental illness as an emergent concept and practice in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2007;53:108–122. doi: 10.1177/0020764006075018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratey J. Spark: the revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, Ross CA. Childhood trauma, psychosis, and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;112:330–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for schizophrenia: from conceptualization to intervention. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47(1):39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Lehman AF. An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(5):540–547. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Researc. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH. Coping with psychosis: An integrative developmental framework. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorder. 2006;194:917–924. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000249108.61185.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D. Recovering from severe mental illness: Mutual influences of self and illness. Journal Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2005;43:35–40. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20051201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D. Progressing from patienthood to personhood across the multidimensional outcomes in schizophrenia and related disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189:691–699. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D, Ben-Yaskai AB. Exploring the relationship between the person and the disorder among individuals hospitalized for psychosis. Psychiatry. 1999;62:372–380. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1999.11024884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum B, Valbak K, Harder S, Knudsen P, Køster A, Lajer M, Lindhardt A, Winther G, Petersen L, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M, Andreasen AH. The Danish National Schizophrenia Project: prospective, comparative longitudinal treatment study of first-episode psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:394–399. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarderude F. Eating one’s words part 3: Mentalizing based psychotherapy for anorexia nervosia, an outline for treatment and a training manual. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15:323–339. doi: 10.1002/erv.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, DiLillo D, Spaulding WD, Silverstein SM. Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;76:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, Spaulding WD, Silverstein SM. Poor premorbid social functioning and theory of mind deficit in schizophrenia: evidence of reduced context processing? Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2005;39:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, Silverstein SM. Dimensions of premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: a review of neuromotor, cognitive, social, and behavioral domains. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 2004;130:241–270. doi: 10.3200/MONO.130.3.241-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles H. Collected papers of schizophrenia and related subjects. New York: International Universities Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Seikkula J, Alakare B, Aaltonen J. Open dialogue in psychosis II: A comparison of good and poor outcomes cases. Journal of Constructivist Psychology. 2001;14:247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Semerari A, Carcione A, Dimaggio G, Falcone M, Nicolo G, Procaci M, Alleva G. How to evaluate metacognitive function in psychotherapy? The Metacognition assessment scale its applications. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2003;10:238–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sensky T, Turkington D, Kingdom D, Scott JL, Scott J, Siddle R, Carrol M, Barnes TRE. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent symptoms in schizophrenia resistant to medication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:165–172. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM. Integrating Jungian and Self-Psychological perspectives within cognitive-behavior therapy for a young man with a fixed religious delusion. Clinical Case Studies. 2007;6:263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM, Bellack AS. A scientific agenda for the concept of recovery as it applies to schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1108–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM, Spaulding WD, Menditto AA. Schizophrenia: Advances in Evidence-based practice. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding WD, Reed D, Sullivan M, Richardson C, Weiler M. Effects of cognitive treatment in psychiatric rehabilitation. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25:657–676. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Hilaire A, Cohen AS, Docherty NM. Emotion word use in the conversational speech of schizophrenia patients. Cognitive NeuroPsychiatry. 2008;13(4):343–356. doi: 10.1080/13546800802250560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratta P, Riccardi I, Mirabilio D, Di Tommaso S, Tomassini A, Rossi A. Exploration of irony appreciation in schizophrenia: a replication study on an Italian sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:337–339. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0729-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Consensus Conference on Mental Health Recovery and Systems Transformation. Rockville MD: Dept of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. Schizophrenia as a human process. New York: Norton; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Swindle R, Heller K, Pescosolido BA, Kikuzawa S. Responses to nervous breakdowns in America over a 40-year period: Mental health policy implications. American Psychologist. 2000;55:740–749. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.7.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Mishara AL. Perceptual anomalies in schizophrenia: integrating phenomenology and cognitive neuroscience. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(1):142–156. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Silverstein SM. Perceptual Organization in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Empirical Research and Associated Theories. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:618–632. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup J, Wei W, Sambamoorthi U, Crystal S, Yanos PT. Provision of psychotherapy for a statewide population of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Psychological Services. 2006;3(4):227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkel R, Stefanis NC, Myin-Germeys I. Psychosocial stress and psychosis: A review of the neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene-stress interaction. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:1095–1105. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zelst C. Which environments for G × E? A user perspective on the roles of trauma and structural discrimination in the onset and course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:1106–1110. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]