Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests mitochondrial alterations are intimately associated with the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In order to determine if mutations of presenilin-1 (PS-1) affect levels of mitochondrial proteins at different ages we enriched mitochondrial fractions from 3-, 6-, 12-month-old knock-in mice expressing the M146V PS-1 mutation and identified, and quantified proteins using cleavable isotope-coded affinity tag labeling and two-dimensional liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (2D-LC/MS/MS). Using this approach, 165 non-redundant proteins were identified with 80 of them present in all three age groups. Specifically, at young ages (3 and 6 months), Na+/K+ ATPase and several signal transduction proteins exhibited elevated levels, but dropped dramatically at 12 months. In contrast, components of the oxidative phosporylation pathway (OXPHOS), the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), and energy metabolism proteins remained unchanged at 3 months but significantly increased with age. We propose that alterations in calcium homeostasis induced by the PS-1 mutation have a major impact in young animals by inhibiting the function of relevant proteins and inducing compensatory changes. However, in older mice combination of the PS-1 mutation and accumulated oxidative damage results in a functional suppression of OXPHOS and MPTP proteins requiring a compensatory increase in expression levels. In contrast, signal transduction proteins showed decreased levels due to a break down in the compensatory mechanisms. The dysfunction of Na+/K+ ATPase and signal transduction proteins may induce impaired cognition and memory before neurodegeneration occurs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-009-9359-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Presenilin mutation, Alzheimer’s disease, Proteomics, LC/MS/MS, Mitochondria

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with pathological hallmarks of synaptic degeneration, senile plaque deposition, and neurofibrillary tangle formation (Selkoe 2002). Although several etiologic hypotheses have been suggested for AD including those centered around oxidative stress, amyloid beta peptide (Aß) deposition, and tau hyperphosphorylation, none of them individually is sufficient to explain the spectrum of abnormalities found in the disease.

Patients with familial or early onset AD (FAD) have been shown to possess genetic mutations of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PS-1), or presenilin 2 (PS-2). To date, 21 different missense APP mutations in 68 families, 10 PS-2 mutations in 18 families, and 164 PS-1 in 361 families have been identified (Brouwers et al. 2008). Although FAD represents only about 5% of all AD cases, these findings form the genetic basis for the development of cellular and animal models of AD. Presenilins are 50-kDa proteins that contain multiple transmembrane domains and reside in the membrane of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Spasic et al. 2006; Selkoe and Wolfe 2007). Mutations in presenilins account for the majority of FAD cases (Papassotiropoulos et al. 2006). Mutations of PS-1 in cell culture and animal models have been found to enhance the production of the amyloidogenic form of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ1-42) (Duff et al. 1996; Newman et al. 2007), leading to disruptions of calcium homeostasis (Begley et al. 1999; Mattson 1998, 2007; Schneider et al. 2001) and increase in oxidative damage (Guo et al. 1997; Schuessel et al. 2006; Leutner et al. 2000). Of particular interest, disruption of cellular calcium homeostasis mediated by PS-1 mutations has been highlighted by recent functional and genetic data as one of the initiators of AD. This is supported by the demonstration that wild-type (WT) presenilins, but not mutated forms, are able to form Ca-permeable channels in the ER (Tu et al. 2006; Nelson et al. 2007). According to the model of ER-mitochondrial crosstalk, neurons expressing mutated PS isoforms experience a reduction in ER calcium flux leading to over-accumulation of Ca2+ in the ER and subsequent transfer to mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal apoptosis (Tu et al. 2006; Giacomello et al. 2007).

Mitochondria are eukaryotic organelles that play a crucial role in several cellular processes, including energy production, ion homeostasis, heme synthesis, fatty acid metabolism, and apoptosis (Nicholls and Budd 2000; Vo and Palsson 2007; Green and Reed 1998). The mitochondrial electron transport chain is the major source of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress (Cadenas and Davies 2000; Bailey et al. 2005; Raha and Robinson 2000). In addition, mitochondria are thought to be high capacity Ca2+ sinks that aid in maintaining cellular Ca2+ homeostasis (Da Cruz et al. 2005). Alternately, increased Ca2+ was found to have a profound impact on the function of mitochondria by activating mitochondrial matrix dehydrogenases to produce more NADH, which donates more electrons to the ETC. through complex I to increase synthesis of additional ATP and more ROS (McCormack et al. 1990; Giacomello et al. 2007). Large amounts of calcium influx would also depolarize the mitochondrial membrane potential in general and the plasma membrane in particular (Cortassa et al. 2003).

Proteins are vital parts of living organisms, as they are the main components of the physiological metabolic pathways of cells. Because of the heterogeneous nature of AD, information provided by non-biased molecular strategies, such as proteomics, should be of great interest. Changes in ion homeostasis and oxidative damage associated with AD would likely be reflected by substantial proteomic alterations and this information is essential for the fundamental understanding of AD pathology (Swerdlow and Khan 2004; Ward 2007; Mootha et al. 2003; Schonberger et al. 2001; Moreira et al. 2007; Bubber et al. 2005). Previous proteomic analyses of AD patients showed significantly decreased levels of synaptosomal-associated protein (SNAP25), 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phospho-diesterase (CNPase), glutamate transporter, excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), ATP synthase alpha chain, creatine kinase (CKMT) B chain, and increased levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (Schonberger et al. 2001; Papassotiropoulos et al. 2006). Organellar proteomics aims to describe the full complement of proteins of subcellular structures and organelles (Huber et al. 2003). Comparing with analyzing whole-cell or whole-tissue, subcellular proteomic studies give more focused results and biologically relevant information can be more easily extracted. Considering the importance of mitochondria in the cellular life and their high association with the development of AD, this study focused on samples of enriched mitochondria.

In our previous study, we used 2D-LC/MS/MS to quantify mitochondrial protein levels from primary neuron cultures treated with Aß and observed significant elevations in proteins associated with energy production (Lovell et al. 2005). In this article, we present the results of mitochondrial protein changes in the brain of PS-1 transgenic mice as a function of age.

Experimental

Materials

All chemicals and antibodies, except otherwise specified, were used as purchased from Aldrich-Sigma without further purification. HPLC reagents and solvents were from Fisher Scientific. Pan-VDAC, VDAC-1, and hexokinase (Hexo) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Anti-adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT) antibody was from Mito Sciences (Abcam Inc.).

PS-1 Knock-in Mice

Knock-in mice expressing the M146V PS-1 mutation (PS-1 KI mice) at normal physiologic levels were obtained from Dr. Mark Mattson (Guo et al. 1999). Genotyping of PS-1 KI and WT mice was as previously described (Guo et al. 1999). For all the experiments, mice bearing human wild-type PS-1 (WT) or the human M146V PS-1 mutation (PS-1 KI) were maintained on a 12-h dark-light cycle with food and water ad libitum. Twelve WT and PS-1 KI mice at 3, 6, and 12 months of age were euthanatized by halothane overdose as per University of Kentucky IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) approved protocols. Brains were quickly removed and cortices immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used for analysis.

Preparation of Enriched Mitochondrial Fractions

The preparation of enriched mitochondrial fractions was previously described with slight modification (Wang et al. 2005). Cortices from three individual PS-1 KI or WT mice of each age (three biological replicate samples per age and animal type) were combined and homogenized on ice in 10 ml MSB-Ca2+ buffer consisting of 0.21 M mannitol, 0.07 M sucrose, 0.5 M Tris–HCl and, 3 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.5) using a motor-driven Teflon-coated Dounce homogenizer. Following homogenization, 1/10 volume of 0.1 M Na2EDTA was added to the solution and it was centrifuged at 1500g and 4°C for 20 min. Following centrifugation the supernatant was removed and centrifuged at 20,000g and 4°C for 20 min. The resulting pellet was washed thrice in MSB-Ca2+ followed by centrifugation. Because this crude pellet was often contaminated with Golgi and cytosolic proteins, the pellet was re-suspended in 2 ml 50/50 Percoll/MSB-Ca2+ and centrifuged at 50,000g for 1 h. Following centrifugation, enriched mitochondria were isolated at a density of ~1.035 g/ml, pelleted, re-suspended in Percoll/MSB-Ca2+, and centrifuged through a second Percoll gradient. The resulting enriched mitochondrial pellet was rinsed thrice in PBS and frozen. In general, yields of mitochondria enriched through two Percoll gradients approached ~200 to 300 μg/g tissue determined using the Pierce BCA method.

Western Blot Analyses

Twenty-five microgram samples of enriched mitochondrial fractions were separated on 12–20% linear gradient SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. The blots were blocked in 5% dry milk in TTBS (Tween®/Tris-buffered salt solution) for 2 h and incubated overnight in rabbit anti-bodies for ANT, uMtCK, Hexo, VDAC1, and Pan-VDAC. The blots were rinsed three to five times in TTBS and incubated 2 h in horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Following three to five washes in TTBS, the bands were observed using enhanced chemoluminescence per manufacturer’s instructions.

ICAT Labeling of Mitochondrial Proteins

For ICAT analyses 100 μg mitochondrial protein from each of three biological replicates of each group of mice were pooled and separated into three 100 μg analytical replicates for ICAT analysis using the commercially available, cleavable ICAT reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described by Hansen et al. (2003) with modification (Lovell et al. 2005). Briefly, triplicate 100 μg samples of mitochondria from WT or PS-1KI mice were solubilized in Tris–SDS (1%) denaturing buffer and heated with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to reduce protein disulfide bonds. Mitochondrial proteins from age-matched WT mice were reacted with light (12C-labeled) ICAT reagent, whereas proteins from PS-1 KI mice were reacted with heavy (13C-labeled) ICAT reagent for 2 h at 37°C. Labeled protein samples were combined and digested with trypsin (1:40 = protease:protein) at 37°C for 16 h. The resulting peptide mixture was then passed through a cation-exchange cartridge to remove TCEP, SDS, and unreacted ICAT reagents. ICAT-labeled peptides in the eluent were isolated on an avidin cartridge and eluted with 30% acetonitrile/70% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (0.4%). The isolated-labeled peptides were evaporated to dryness, resuspended in TFA and incubated for 2 h at 37°C to cleave the biotin portion of the ICAT tags. ICAT-labeled peptides were evaporated to dryness, reconstituted in 10 μl 5% acetonitrile/95% aqueous formic acid (0.1%) prior to 2D-LC/MS/MS.

Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Peptides were separated using 2D-HPLC on a laboratory-packed capillary strong cation exchange and reverse phase C18 resin columns. After loading, thirteen 0 to 300 mM ammonium acetate injections were used to elute the peptides from the cation exchange phase. Each salt fraction was then subjected to a complete reverse phase gradient from 5% acetonitrile/95% aqueous formic acid (0.1%) to 70% acetonitrile/30% aqueous formic acid (0.1%) over 110 min. Salt and organic gradients were generated using LC Packings Ultimate HPLC pumps at a solvent flow of 4 μl/min. the HPLC system was coupled on-line with a ThermoFinningan LCQ Deca quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer to acquire LC/MS/MS spectra in a data-dependent mode. Three spectra were averaged to generate the full-scan spectrum with only the most intense ion subjected to MS/MS so that the greatest number of full scans can be obtained for reliable quantification. Five spectra were averaged to produce the MS/MS spectrum. Masses subjected to MS/MS were excluded from further MS/MS for 2 min.

Mass Spectrometric Data Analysis

SEQUEST database searches were carried out using the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline software developed by Seattle Proteome Center. Briefly, raw files of the MS/MS Spectra were converted into standard mzXML files, and automated database searching using SEQUEST™ software (MacCoss et al. 2003) was performed to identify peptide and protein sequence matches against a locally maintained mouse protein sequence database. SEQUEST™ search was carried out on both “light” and “heavy” peptides making the light label a fixed modification (227.2) and heavy label (addition of 9 to the mass value of light label) as a variable modification using default SEQUEST parameters. SEQUEST™ output files were then submitted to PeptideProphet™ (Keller et al. 2002) for computation of the probability that each peptide sequence assignment is correct (P comp). The resultant outputs from SEQUEST™ and PeptideProphet™ were filtered at different P comp cut-offs, and its sorting functions were used to determine the number of “single hit” peptides and proteins that were contained within each filtered version of the data. These output files were submitted to ProteinProphet™ which utilizes the list of peptide sequences and their respective P comp scores to determine a minimal list of proteins (database entries) that can explain the observed data and to compute a probability (P comp) that each protein was indeed present in the original sample(s) (Nesvizhskii et al. 2003). The XPRESS software automates protein expression calculations by accurately quantifying the relative abundance of “heavy” and “light” peptides from their chromatographic coelution profiles. Xpress calculates the molecular weights of the “light” peptides related to the identified “heavy” peptides and vice versa (Han et al. 2001). Based on the peptide identification, the “light” and “heavy” peptide elution profiles are detected, the area of each peptide peak is determined, and the abundance ratio is calculated based on these areas to obtain (A heavy/A light)pep. The protein ratio was calculated by averaging the peptide ratio values to obtain the relative abundance ratios of the protein,

|

where n is the total number of peptide identifications (including redundant identifications).

Statistical Comparison

Mean and standard deviations were obtained from three analytical replicates. Results were compared using ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test and the commercially available ABSTAT software (AndersonBell, Arvada, CO). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

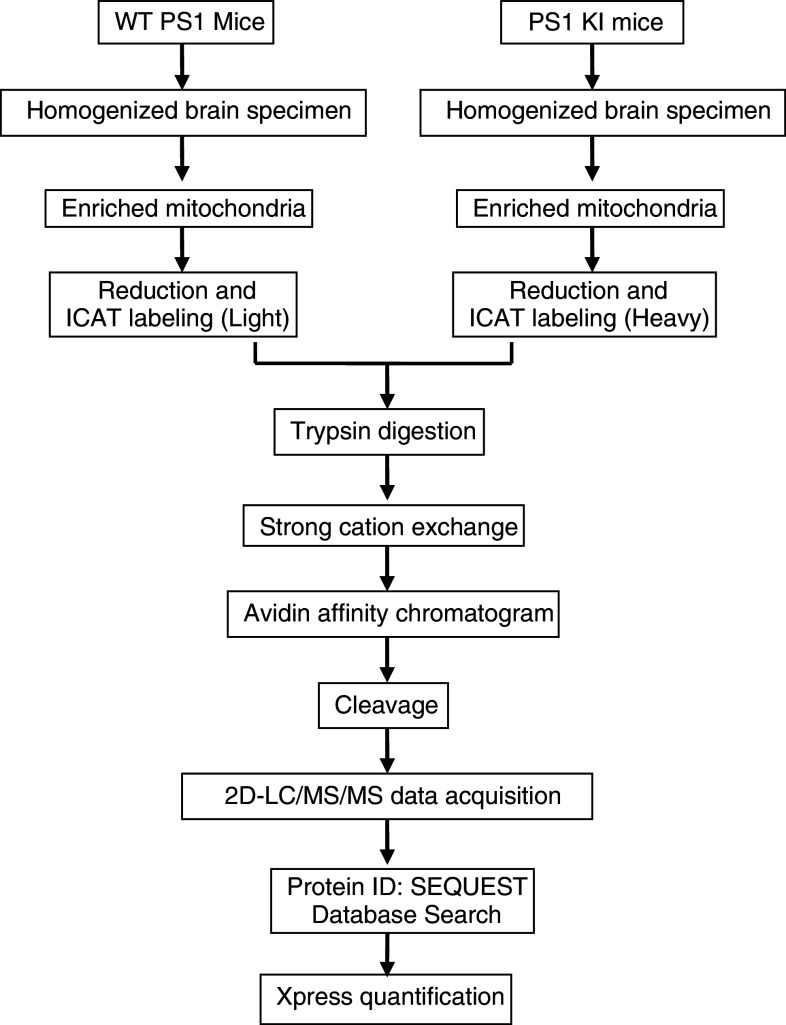

The experimental work flow is shown in Fig. 1. Mouse genotyping was verified as previously described (Guo et al. 1999). Knock-in mice expressing the M146V PS-1 mutation at normal physiological levels show no overt phenotypic mutations, but have shown to be hypersensitive to seizure-induced synaptic degeneration (Guo et al. 1999). In addition, previous studies show no age-dependent hippocampal neuron loss in PS1 KI mice up to ~12 months of age (Guo et al. 1999) although they show age-related loss of synaptophysin immunoreactive presynatpic boutons in the stratum radiatum of CA1-2 of hippocampus (Rutten et al. 2005). More recent studies show increased lipid peroxidation in the brain of aged (19–22-month-old) PS-1 KI mice but not in younger (13–15-month-old) mice (Schuessel et al. 2006). In the studies of hippocampal spatial memory using the Morris Water Maze Task, PS-1 KI mice show decreased quadrant occupancy and platform crossing beginning at 3 months of age that return to normal after 12 days of training. In contrast, older (9-month-old) animals showed reduced platform crossing that remained altered after 12 days of training, suggesting an age-dependent impairment of hippocampal spatial memory (Sun et al. 2005).

Fig. 1.

Experimental work flow

Proteomic analysis of mitochondrial samples from 3-, 6-, and 12-month-old PS-1 KI and age-matched WT mice using ICAT labeling, 2D-LC/MS/MS, SEQUEST™ database searches, and validation by PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet programs identified 165 non-redundant proteins (Table S1 as supplemental materials). Figure 2 shows statistical validation of SEQUEST-generated peptide and protein identifications from a mitochondrial protein sample. The Xpress software was used to calculate the peak area ratios from each heavy and light peptide elution profiles. A protein identity was assigned as valid if its protein probability was >0.45 (5% error rate) from the ProteinProphet calculation and if it was identified in at least two of the three replicates in the particular age group. Out of the total, 82 proteins were identified as mitochondrial proteins based on subcellular localization in SwissProt. Because protein levels in PS-1 KI mitochondria are expressed as a function of levels in age-matched WT mice, we are able to identify proteins that undergo a substantial change with age that are due to the presence of the PS-1 mutation. Tables 1, 2, and 3 list proteins identified and quantified in all the three age groups. The proteins were grouped into the three tables according to the pattern of change associated with age. Thirty-two proteins showed a significant increase (Table 1), 14 proteins showed significant decreases (Table 2), and 25 proteins showing no significant alteration (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Statistical validation of SEQUEST-generated peptides (top panel) and protein identifications (bottom panel) from one of the mitochondrial protein samples. The well-separated model positive (model pos) and model negative (model neg) peaks indicate high confidence of the peptide identification. Parameter, fval, is an intermediate PeptideProphet score. A probability of 0.45 stands for greater than 97% sensitivity and less than 5% error rate for the protein identification

Table 1.

Proteins identified from mitochondria of PS1 transgenic mice showing increasing relative abundances versus that of control littermates at the same age from young (3 and 6 months) to old (12 months) ages

| No. | Protein access number and description | Age (month) | ANOVA-test (P < 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 3–6 | 3–12 | 6–12 | ||

| 1 | P08249|MDHM_MOUSE Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.1.1.37) | 1.06 (0.09) | 1.13 (0.02) | 1.92 (0.21) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | P05202|AATM_MOUSE Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.6.1.1) (Transaminase A) (Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 2) | 1.04 (0.02) | 1.06 (0.05) | 1.74 (0.15) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Q8BH59|CMC1_MOUSE Calcium-binding mitochondrial carrier protein Aralar1 (Solute carrier family 25 member 12) | 1.11 (0.07) | 0.95 (0.08) | 2.12 (0.13) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Q9CPP6|NDUA5_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 5 (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I subunit B13) | 0.94 (0.04) | 1.10 (0.14) | 1.59 (0.09) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Q9DCJ5|NDUA8_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 8 (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I–19 kDa) | 0.98 (0.05) | 1.14 (0.01) | 2.03 (0.26) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Q9Z1P6|NDUA7_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 7 (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I-B14.5a) | 1.25 (0.18) | 1.23 (0.11) | 3.11 (0.38) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Q91YT0|NDUV1_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I—51 kDa) | 1.09 (0.09) | 1.06 (0.09) | 1.58 (0.23) | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | Q91VD9|NDUS1_MOUSE NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I—75 kDa) | 0.95 (0.01) | 1.09 (0.09) | 1.77 (0.12) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Q8K2B3|DHSA_MOUSE Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.3.5.1) (Fp) (Flavoprotein subunit of complex II) | 1.01 (0.04) | 0.98 (0.04) | 1.63 (0.06) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Q9CQA3|DHSB_MOUSE Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.3.5.1) (Ip) (Iron-sulfur subunit of complex II) | 0.93 (0.05) | 1.08 (0.11) | 1.87 (0.39) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Q9CZ13|UQCR1_MOUSE Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase complex core protein I, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.10.2.2) | 1.00 (0.09) | 1.28 (0.09) | 2.12 (0.22) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | P19536|COX5B_MOUSE Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5B, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.9.3.1) | 0.84 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.07) | 1.81 (0.03) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Q91VR2|ATPG_MOUSE ATP synthase gamma chain, mitochondrial precursor (EC 3.6.3.14) | 0.90 (0.06) | 0.93 (0.10) | 1.86 (0.21) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | Q9DCX2|ATP5H_MOUSE ATP synthase D chain, mitochondrial (EC 3.6.3.14) | 0.87 (0.03) | 1.13 (0.06) | 1.72 (0.27) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Q03265|ATPA_MOUSE ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial precursor (EC 3.6.3.14) | 0.80 (0.03) | 0.72 (0.10) | 1.53 (0.13) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | Q99KI0|ACON_MOUSE aconitate hydratase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 4.2.1.3) (Citrate hydrolyase) (Aconitase) | 1.04 (0.07) | 1.08 (0.10) | 1.93 (0.32) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | Q9CZU6|CISY_MOUSE citrate synthase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.3.3.1) | 0.93 (0.14) | 1.06 (0.04) | 1.73 (0.15) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Q9D6R2|IDH3A_MOUSE Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NAD] subunit alpha, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.1.1.41) (NAD(+)-specific ICDH) | 0.94 (0.02) | 1.18 (0.05) | 1.52 (0.18) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | Q60932|VDAC1_MOUSE voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC-1) (mVDAC1) (mVDAC5) (Outer mitochondrial membrane protein porin 1) (Plasmalemmal porin) | 0.95 (0.02) | 1.21 (0.10) | 1.79 (0.10) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | Q60930|VDAC2_MOUSE voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 (VDAC-2) (mVDAC2) (mVDAC6) (Outer mitochondrial membrane protein porin 2) | 0.99 (0.12) | 0.95 (0.06) | 1.52 (0.12) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | P48962|ADT1_MOUSE ADP/ATP translocase 1 (Adenine nucleotide translocator 1) (ANT 1) (ADP,ATP carrier protein 1) (Solute carrier family 25 member 4) | 0.97 (0.05) | 1.21 (0.06) | 2.19 (0.18) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | P30275|KCRU_MOUSE CKMT, ubiquitous mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.7.3.2) (U-MtCK) | 0.88 (0.02) | 1.11 (0.08) | 1.77 (0.23) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | P17710|HXK1_MOUSE Hexo-1 (EC 2.7.1.1) (Hexo type I) (HK I) | 0.97 (0.04) | 1.13 (0.10) | 1.93 (0.11) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | P05708|HXK1_RAT Hexo-1 (EC 2.7.1.1) (Hexo type I) (HK I) | 0.98 (0.16) | 0.89 (0.07) | 1.86 (0.16) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Q9CPU4|MGST3_MOUSE Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 (EC 2.5.1.18) | 0.97 (0.05) | 1.12 (0.09) | 1.58 (0.02) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 26 | Q9DCZ4|F121B_MOUSE Protein FAM121B | 1.04 (0.16) | 1.12 (0.10) | 2.05 (0.09) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 27 | O55125|NIPS1_MOUSE Protein NipSNAP1 | 1.14 (0.14) | 1.19 (0.07) | 1.78 (0.08) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 28 | Q91WS0|ZCD1_MOUSE Zinc finger CDGSH domain-containing protein 1 | 1.17 (0.08) | 1.09 (0.09) | 1.85 (0.29) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 29 | P13264|GLSK_RAT Glutaminase kidney isoform, mitochondrial precursor (EC 3.5.1.2) (GLS) | 1.03 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.07) | 1.69 (0.05) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 30 | Q9DB77|UQCR2_MOUSE Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase complex core protein 2, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.10.2.2) (Complex III subunit II) | 0.84 (0.04) | 0.90 (0.01) | 2.16 (0.10) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 31 | P08461|ODP2_RAT Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue acetyltransferase component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.3.1.12) | 1.13 (0.21) | 1.21 (0.14) | 1.80 (0.01) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 32 | Q91VN4|CHCH6_MOUSE Coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain-containing protein 6 | 0.90 (0.08) | 1.07 (0.12) | 1.45 (0.14) | No | Yes | Yes |

Table 2.

Proteins identified from mitochondria of PS1 transgenic mice showing decreasing relative abundance versus that of control littermates at the same age from young (3 and 6 months) to old (12 months) ages

| No. | Protein access number and description | Age (month) | ANOVA-test (P < 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 3–6 | 3–12 | 6–12 | ||

| 1 | Q6PIE5|AT1A2_MOUSE Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase alpha–2 chain precursor (EC 3.6.3.9) | 1.69 (0.07) | 1.56 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.01) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | P14094|AT1B1_MOUSE Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit beta-1 | 1.50 (0.14) | 1.51 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.00) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Q6PIC6|AT1A3_MOUSE Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase alpha-3 chain (EC 3.6.3.9) | 1.69 (0.11) | 1.38 (0.05) | 0.53 (0.04) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | P62874|GBB1_MOUSE Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta 1 | 1.53 (0.17) | 0.99 (0.03) | 0.65 (0.12) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | P16330|CN37_MOUSE 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.37) (CNP) (CNPase) | 1.61 (0.11) | 1.22 (0.11) | 0.83 (0.04) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | P68254|1433T_MOUSE 14-3-3 protein theta (14-3-3 protein tau) | 1.49 (0.17) | 1.42 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.06) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | P43006|EAA2_MOUSE EAAT2 (GLT-1) | 1.80 (0.32) | 1.29 (0.21) | 0.47 (0.04) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Q04447|KCRB_MOUSE CKMT B-type (EC 2.7.3.2) (B-CK) | 1.96 (0.18) | 1.31 (0.03) | 0.49 (0.02) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Q9R0P9|UCHL1_MOUSE Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 (EC 3.4.19.12) (EC 6.-.-.-) (UCH-L1) | 1.42 (0.03) | 1.07 (0.14) | 0.40 (0.01) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | P02088|HBB1_MOUSE Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 (Hemoglobin beta-1 chain) | 1.75 (0.22) | 1.18 (0.08) | 0.65 (0.07) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | P60710|ACTB_MOUSE Actin, cytoplasmic 1 (Beta-actin) | 1.34 (0.35) | 1.10 (0.09) | 0.54 (0.09) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | P35802|GPM6A_MOUSE Neuronal membrane glycoprotein M6-a (M6a) | 1.43 (0.05) | 1.18 (0.05) | 0.41 (0.09) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Q8VDQ8|SIRT2_MOUSE NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-2 (EC 3.5.1.-) (SIR2-like protein 2) (mSIR2L2) | 1.29 (0.14) | 0.88 (0.12) | 0.68 (0.06) | Yes | Yes | No |

| 14 | P63213|GBG2_MOUSE Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(O) gamma-2 subunit precursor (G gamma-I) | 1.42 (0.20) | 1.42 (0.15) | 0.50 (0.07) | No | Yes | Yes |

Table 3.

Proteins identified from mitochondria of PS1 transgenic mice showing no significant relative abundance change versus control littermates at the same age from young (3 and 6 months) to old (12 months) ages

| No. | Protein access number and description | Age (month) | ANOVA-test (P < 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 3–6 | 3–12 | 6–12 | ||

| 1 | Q99LC3|NDUAA_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 10, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I—42 kDa) | 0.99 (0.05) | 1.05 (0.06) | 1.17 (0.20) | No | No | No |

| 2 | P99028|UCRH_MOUSE Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex 11 kDa protein, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.10.2.2) (Complex III subunit VIII) | 0.88 (0.05) | 1.08 (0.08) | 1.54 (0.43) | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | Q64521|GPDM_MOUSE Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.1.99.5) (GPD-M) | 1.04 (0.04) | 1.05 (0.10) | 1.17 (0.13) | No | No | No |

| 4 | P99029|PRDX5_MOUSE Peroxiredoxin-5, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.11.1.15) (Prx-V) | 0.89 (0.07) | 1.07 (0.11) | 1.12 (0.12) | No | No | No |

| 5 | Q9D0K2|SCOT_MOUSE Succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase 1, mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.8.3.5) | 0.81 (0.01) | 1.09 (0.13) | 1.26 (0.07) | Yes | Yes | No |

| 6 | P68369|TBA1_MOUSE Tubulin alpha-1 chain (Alpha-tubulin 1) | 1.42 (0.09) | 1.12 (0.09) | 0.94 (0.02) | No | Yes | No |

| 7 | P68368|TBA4_MOUSE Tubulin alpha-4 chain (Alpha-tubulin 4) | 1.22 (0.09) | 1.06 (0.04) | 1.12 (0.15) | Yes | No | No |

| 8 | Q7TMM9|TBB2A_MOUSE Tubulin beta-2A chain | 1.05 (0.43) | 1.06 (0.14) | 0.66 (0.14) | No | No | Yes |

| 9 | P26443|DHE3_MOUSE Glutamate dehydro-genase 1, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.4.1.3) (GDH) | 1.02 (0.10) | 1.20 (0.09) | 1.38 (0.09) | No | Yes | No |

| 10 | P11798|KCC2A_MOUSE Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II alpha chain (EC 2.7.11.17) (CaM-kinase II alpha chain) | 1.12 (0.08) | 1.25 (0.03) | 0.95 (0.21) | No | No | No |

| 11 | Q9CR21|ACPM_MOUSE Acyl carrier protein, mitochondrial precursor (ACP) (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 9.6 kDa subunit) (CI-SDAP) | 1.09 (0.13) | 0.99 (0.05) | 1.36 (0.07) | No | No | Yes |

| 12 | Q9QYG0|NDRG2_MOUSE Protein NDRG2 (Protein Ndr2) | 0.90 (0.10) | 1.04 (0.03) | 0.75 (0.07) | No | No | Yes |

| 13 | O08599|STXB1_MOUSE Syntaxin-binding protein 1 (Unc-18 homolog) (Unc-18A) (Unc-18-1) | 1.41 (0.05) | 1.18 (0.05) | 1.54 (0.89) | Yes | No | No |

| 14 | P62814|VATB2_MOUSE Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit B, brain isoform (EC 3.6.3.14) | 1.27 (0.24) | 1.24 (0.40) | 0.59 (0.02) | No | Yes | No |

| 15 | P60202|MYPR_MOUSE Myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) (Lipophilin) | 1.74 (0.23) | 1.44 (0.12) | 1.05 (0.11) | No | Yes | No |

| 16 | Q8VEM8|MPCP_MOUSE Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial precursor (PTP) (Solute carrier family 25 member 3) | 1.30 (0.22) | 1.09 (0.09) | 1.70 (0.14) | No | No | Yes |

| 17 | Q8BFR5|EFTU_MOUSE Elongation factor Tu, mitochondrial precursor | 1.00 (0.11) | 1.11 (0.13) | 2.06 (0.42) | No | No | No |

| 18 | Q60931|VDAC3_MOUSE Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 3 (VDAC-3) (mVDAC3) (Outer mitochondrial membrane protein porin 3) | 1.92 (0.24) | 1.27 (0.28) | 2.19 (0.57) | No | No | No |

| 19 | O08749|DLDH_MOUSE Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.8.1.4) (Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase) | 1.09 (0.09) | 1.10 (0.06) | 1.77 (0.27) | No | No | No |

| 20 | Q9D0M3|CY1_MOUSE Cytochrome c1, heme protein, mitochondrial precursor (Cytochrome c-1) | 0.99 (0.01) | 1.15 (0.03) | 1.69 (0.27) | Yes | No | No |

| 21 | Q9CR61|NDUB7_MOUSE NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 7 (EC 1.6.5.3) (Complex I-B18) | 1.01 (0.06) | 1.31 (0.05) | 2.03 (0.56) | Yes | No | No |

| 22 | Q9D6M3|GHC1_MOUSE Mitochondrial glutamate carrier 1 (GC-1) (Glutamate/H(+) symporter 1) (Solute carrier family 25 member 22) | 1.00 (0.13) | 1.19 (0.23) | 2.11 (0.46) | No | Yes | No |

| 23 | Q791V5|MTCH2_MOUSE Mitochondrial carrier homolog 2 | 1.07 (0.02) | 0.90 (0.04) | 1.39 (0.20) | Yes | No | Yes |

| 24 | P63038|CH60_MOUSE 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial precursor (Hsp60) (60 kDa chaperonin) (CPN60) (Mitochondrial matrix protein P1) (HSP-65) | 0.94 (0.03) | 1.15 (0.16) | 1.87 (0.35) | No | Yes | No |

| 25 | Q9D172|ES1_MOUSE ES1 protein homolog, mitochondrial precursor | 0.86 (0.11) | 0.93 (0.01) | 0.86 (0.11) | No | No | No |

Table 1 shows proteins that were significantly increased in PS-1 mice in an age-dependent manner. The first three proteins are components of the malate-aspartate shuttle. These proteins show no change in levels at 3 and 6 months, but show significantly increased levels in PS-1 KI mice at 12 months. For example, levels of aspartate aminotransferase were 1.04 (±0.02) and 1.06 (±0.05) at 3 and 6 months, respectively, but increased to 1.74 (±0.15) at 12 months. The next 12 proteins in Table 1 are different subunits in the electron transfer chain complexes, I, II, III, IV, V and showed significant age-dependent increases in PS-1 KI mice. Although these proteins show no significant alteration in levels in young mice (3 and 6 months), mice at 12 months of age showed a significant increase with relative expression ratios of 1.5 to 3.0. Other proteins showing significantly increased levels include voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) proteins, ANT, Hexos, creatine kinase (u-MtCK), aconitase hydratase, citrate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD) subunit alpha, mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit (Tim9), microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3.

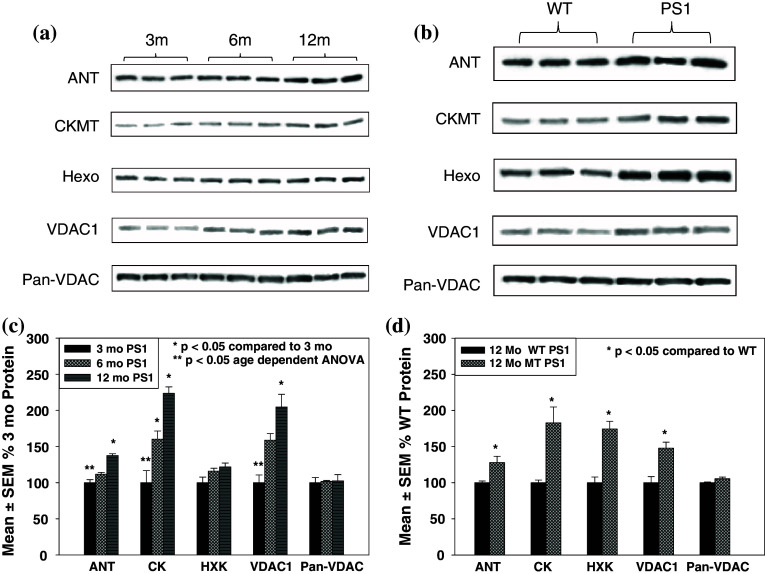

These expression changes were consistent with Western blot results for ANT, CKMT, Hexo, VDAC1, and Pan-VDAC (a mixture of VDAC proteins), as is shown in Fig. 3a and b. Figure 3a shows the results from PS-1 KI mice of different ages. Obvious age-dependent increases in the expression of these proteins can be observed. Figure 3b compares the results of this same protein group from the 12-month PS-1 transgenic and 12-month WT animals. Figure 3c and d shows mean ± SEM changes in these proteins.

Fig. 3.

Western blot experimental results for ANT, CKMT, HXK, and VDAC1, Pan-VDAC. a Comparison among three ages with three replicates for each age of the PS-1 mutant; b Comparison between mutant and WT PS-1 transgenic mice at 12 months; c, d the respective histogram diagrams of (a) and (b) showing mean ± SEM changes in these proteins

Three subunits of Na+/K+ transporting ATPase (Table 2) show a significant decrease in PS-1 KI mice as a function of age. Although the differences between the 3- and 6-month-old animals are not significant, both are significantly different from 12-month-old mice. Interestingly, all the three subunits were significantly higher in 3-month-old PS-1 KI mice compared to age-matched WT mice (~150%). In contrast, 12-month-old PS-1 KI mice showed Na+/K+ transporting ATPase levels that were ~50% of age-matched WT mice. Similar alterations were observed in the expressions of several signal transduction proteins, including subunits of adenine nucleotide binding protein (G-proteins), CNP, and so on.

Other potentially interesting proteins, such as, peroxiredoxin-5, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.11.1.15), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor (EC 1.1.99.5), sarcoplasmic/ER calcium ATPase 2, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II alpha chain (CaMK-II subunit alpha), calreticulin precursor (CRP55) (calregulin), protein NDRG2 (Protein Ndr2), succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase 1, mitochondrial precursor (EC 2.8.3.5), NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 10 (EC 1.6.5.3), acyl carrier protein, mitochondrial precursor (ACP) (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 9.6-kDa subunit), did not change significantly with age (Table 3).

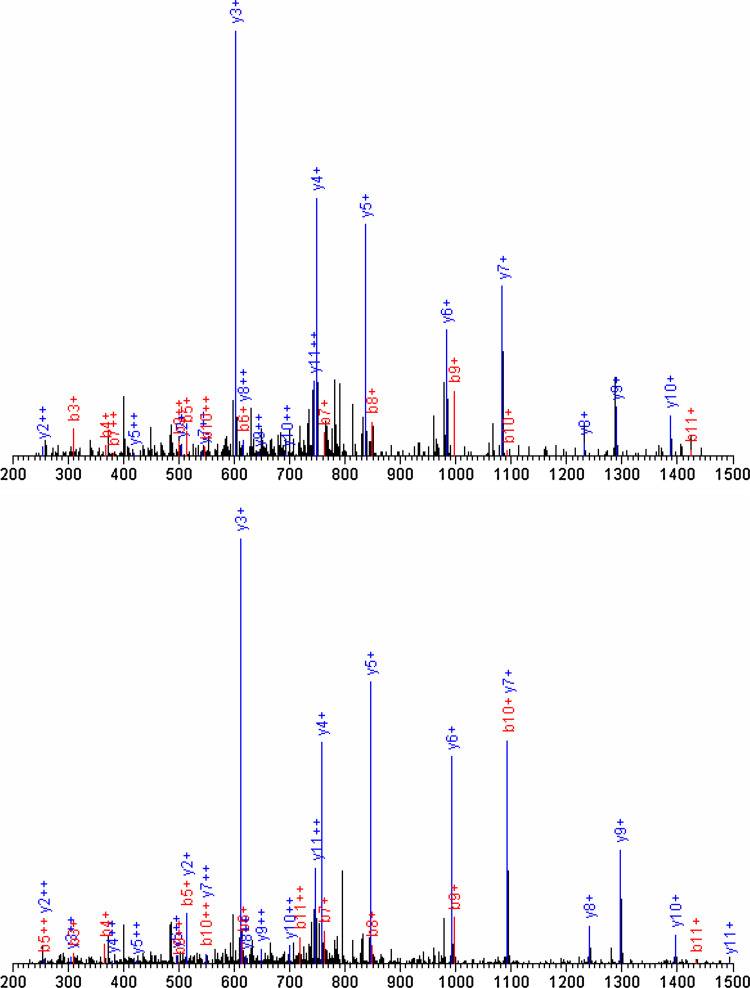

Representative tandem mass spectra and SEQUEST sequencing results are shown in Fig. 4. The precursors of the spectra were identified in the light LPVGFTFSFPCR (1597.9) and heavy format LPVGFTFSFPC*R (1606.9), both in doubly charged states. They are from P17710|HXK1_MOUSE, Hexo-1 with the two cysteine residues modified either by light (227.2) or by heavy (236.2) ICAT tag. The 12 amino acid residue peptide exhibit fragments b2–b11, and y2–y11. The smaller fragments, b1 and y1, did not show up because of the low-mass cut-off effect of the ion trap mass spectrometer.

Fig. 4.

A pair of typical tandem mass spectra and the SEQUEST sequencing results. Peptides, LPVGFTFSFPCR (light, 1597.9, top panel) and LPVGFTFSFPC*R (heavy, 1606.9, bottom panel) from P17710|HXK1_MOUSE, Hexo-1. The 12 amino acid residue peptide (2+) generated fragments b2–b11, and y2–y11 in either format

Discussion

Aging is one of the major risk factors of AD. Mitochondria play crucial roles in the aging process (Dencher et al. 2007). The combination of genetic mutation and aging forms the basis of FAD pathology. Our experiments were designed to examine the impact of the PS-1 mutation on the mitochondrial proteome in KI mice as a function of age. There are several factors that make mitochondrial proteomic analysis difficult: (1) mitochondria form only a small fraction of the total whole cell lysates; (2) mitochondrial samples are prone to contamination from cytoplasmic structural and housekeeping proteins; (3) many mitochondrial proteins are membrane proteins with high hydrophobicity and poor solubility. Thus, mitochondrial proteins are difficult to analyze directly from total cell lysates or tissue protein samples even with the most sensitive methods (Kinnoshita et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2004). We chose to use cellular fractionation methods to enrich mitochondria from most of their interferences so that the proteome of this organelle can be probed (Reinders et al. 2006).

Proteomics analysis was carried out on 3-, 6-, 12-month-old PS-1 trangenic mice (Fig. 1) with three replicates analyzed at each age. A stable isotope labeling strategy, cleavable isotope-coded affinity tagging (ICAT) was used for quantitative purposes (Gygi et al. 2002; Hansen et al. 2003). The ICAT technique employs a thiol-specific tag to assess protein sulfhydryl groups so it was also used as a means for enrichment of proteins containing cysteine residues. In this study, mitochondrial proteins were prepared from PS-1 KI and WT mice and followed by differential isotopic labeling of these samples with either light (12C9) or heavy (13C9) ICAT reagent, respectively (Fig. 1). Database searches based on SEQUEST coupled with PeptideProphet™ were used to further verify the peptide identification and give a unique probability score P pep for each peptide instead of multiple scores as in the traditional SEQUEST search. The well-separated “correct” and “incorrect” curves in Fig. 2a suggest high data quality in this study. The probability score for each protein represents a combination of the error rate and sensitivity (Fig. 2b). The combination of mitochondrial enrichment, ICAT labeling, and 2D-LC/MS/MS allowed identification of 165 unique proteins from the mitochondria of PS-1 M146V transgenic mice (Table S1, supplementary materials), among which 82 (48.5%) proteins were confirmed mitochondrial proteins. Further more, extensive protein expression changes were observed from the quantitative results.

Knock-in mouse models with human PS-1 mutants have been reported to exhibit calcium homeostasis disruption, increased oxidative stress, and abnormal expression of Aβ peptides with a higher ratio of pathogenic Aβ1-42 to Aβ1-40 (Duff et al. 1996). Direct experimental evidence of these changes has been extensively observed (Duff et al. 1996; Guo et al. 1999; Schneider et al. 2001; Schuessel et al. 2006; Parihar and Brewer 2007; Mattson 1998, 2007). The results of this study attempt to address whether mutations of PS-1 can induce alterations of the mitochondrial proteome. Please note although we did observe the age-dependent abundance change of several proteins in PS-1 KI mice from Western blot experiments (Fig. 3a, c) our focus will be on the alterations of the relative protein expressions of age-matched PS-1 KI versus WT mice. The following discussion will be based on (1) the assumption that the relative increases or decreases of proteins in PS-1 KI versus WT PS-1 mice were the results of the mutation, and (2) the observation that these relative expression values showed age-dependent changes.

Proteins Exhibiting Increasing Expressions at 12 Months

The compensatory response of mitochondria in mice with APP mutations was previously reported using gene expression profiles of transcripts (Reddy et al. 2004). Through the study on 3-, 9-, 16-month-old mice, the authors demonstrated an up-regulation of mitochondrial metabolic and apoptotic genes which was suggested to be an early cellular change in both the transgenic models and AD patients (Reddy et al. 2004). Consistent with their results, our data show increased abundances of the proteins, suggesting increased expression possibly as a result of compensatory responses of protein expression to the damage of the protein functions.

The impact of PS-1 mutations on calcium homeostasis is of special interest and has been extensively studied (Bojarski et al. 2008; Mattson 2007). Recently, PS-1 was identified as a passive Ca2+ channel that leaks Ca2+ from ER, and mutations linked with FAD are responsible for much of the elevated Ca2+ concentration in cytosol of neurons and peripheral cells (Tu et al. 2006; Nelson et al. 2007). This altered Ca2+ regulation has been found to have profound effects on the function of multiple proteins. Most interestingly, elevated Ca2+ concentration was reported to activate the malate-aspartate NADH shuttle and causes an increase in the mitochondrial NADH/NAD ratio (Pardo et al. 2006; Contreras et al. 2007; Palmieri et al. 2001). It is possible that this change could induce increased production of ATP, but it may also generate more ROS (Parihar and Brewer 2007). As a result, PS-1 mutations may enhance ROS generation of mitochondria through altered calcium homeostasis. With age, oxidative stress increases and accumulation of oxidative damage leads to damaged proteins and the compensatory responses will increase their expression levels relative to that in WT mice at the same age.

The proteins listed in Table 1 show no significant changes in PS-1 KI mice at 3 and 6 months of age, but showed significant increases at 12 months. Using ICAT labeling, we were able to identify and quantify a total of 27 subunits of the respiratory chain (30% of the 90 in total) (Table S1, supplementary materials) from the samples. Twelve of the oxidative phosporylation pathway (OXPHOS) proteins were observed in all the three age groups. Their relative expression values (PS-1 KI/WT) were ~1 in both 3- and 6-month-old animals, but all increased significantly to levels approximately 150–200% those of WT mice at 12 months of age. Consistent with the current observation, we previously observed elevated expression of ATP synthase (Complex V) in mitochondria from primary rat neuron cultures treated with Aβ (Lovell et al. 2005).

Using ICAT labeling our study identified and quantified ~30% of OXPHOS proteins including a group of proteins which use Fe–S clusters (Fe, Fe2S2, Fe4S4) as their active centers. In the electron transport chain, complexes I, II, IV contain Fe–S proteins which typically have at least four cysteine residues in certain patterns of sequence arrangement (Beinert et al. 1997). Another typical and extensively studied Fe–S protein is aconitase which functions in the Krebs cycle to convert citrate to isocitrate through stereo-specific isomerization. The Fe–S proteins have the common character that their Fe–S cluster prosthetic group is vulnerable to oxidation which would change the coordination conformation, and as a result impair protein functions (Beinert et al. 1996). Oxidative stress caused by ROS (especially, O2 −) will typically disrupt the Fe–S cluster structure without modifying the apoproteins.

In addition to aconitase, we also identified/quantified six other proteins that function in the Krebs cycle. Isocitrate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, malate dehydrogenase showed a significant increase in expression with age in PS-1 KI mice similar to OXPHOS proteins. In contrast, succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase (Succinyl-CoA synthetase), 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component (α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) showed no significant change. Succinate dehydrogenase is the only protein that functions both as a component of complex II in the respiratory chain and in the Krebs cycle. It was reported that the control of organelle metabolic activity is one of the best characterized functions of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Three crucial metabolic enzymes within the matrix (pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, and isocitrate dehydrogenases) are activated by Ca2+, using two distinct mechanisms. In the case of pyruvate dehydrogenase, a Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation step is involved; in the other two cases, the activation is through direct binding of Ca2+ to the enzyme complex.

The malate-aspartate shuttle transports the reduction equivalents of cofactor NADH produced in the cytosol across the inner membrane of the mitochondrion to reach the electron transport chain for oxidative phosphorylation. Three of the four components (malate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and glutamate aspartate transporter) showed increased expression in PS-1 KI mice as a function of age. There were no significant alterations in the expression of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the PS-1 KI mice relative to WT mice for young animals. Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase converts dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol-3-phosphate by oxidizing one molecule of NADH to NAD+ functions as another shuttle in transporting reducing equivalents, secondary to the malate-aspartate shuttle.

Another group of proteins of special interest for mitochondrial function consists of components of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), i.e., adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), the mitochondrial inner membrane protein transporter (TIM), the outer membrane protein transporter (TOM), VDACs, and cyclophilin-D. Similar to that of the electron transfer chain complexes, expression levels of VDACs, ANT, uMtCK, and Hexo remain unchanged in young animals, but increased in 12-month-old animals. We observed two TIMs and one TOM protein in our study although only one TIM was quantified in all the three ages and exhibited a significant elevation at 12 months of age. The MPTP forms at sites where the inner and outer membranes of the mitochondria meet (Berkich et al. 2007; Schlattner et al. 2001). The concerted operation of these proteins creates a channel through which molecules <1.5 kDa pass. Opening of this non-selective channel in the inner membrane allows for an equilibration of ions within the matrix and intermembrane space of mitochondria, thus dissipating the H+ gradient across the inner membrane and uncoupling the respiratory chain.

Our ICAT results were well verified by the Western blot results for ANT, CK, HXK, VDAC1, and Pan-VDAC. As is shown in Fig. 3c, statistical analyses showed significant age-dependent changes of ANT, CK, VDAC1 between 3 and 12 months, but Hexo showed no significant change. Figure 3d shows results of PS-1 KI mice in comparison to WT mice at 12 months of age. ANT, CK, HXK, and VDAC1 all showed significant increases reflecting the major impact of the PS-1 mutation. The non-significant statistical results from Pan-VDAC suggested that although VDAC1 exhibited elevated expression with age, other subunits might change at contrary direction and compromise the result in total.

The major function of uMtCK is to catalyze the reversible transfer of high-energy phosphate from ATP to creatine, yielding phosphocreatine for energy storage and transport. In brain, the cytosolic brain-type CK (BCK) and uMtCK comprise an energy shuttling system, which transfers energy efficiently from the site of ATP production (mitochondria) to distal parts of the cell where energy is consumed. uMtCK was also reported to affect mitochondrial transport and ionic homeostasis by forming a high-energy channeling complex together with VDACs and ANT in mitochondrial contact sites (Schlattner et al. 2001). A direct interaction between the C-terminal region of APP family proteins and uMtCK was reported which stabilizes the immature form of uMtCK in cultured cells (Li et al. 2006). More interestingly, the cytosolic BCK (B chain) and uMtCK showed contrary abundance alterations in the PS-1 mutant mice. While uMtCK showed no change in young animals but increased in 12-month-old animals, the cytosloic BCK showed high levels in young animals but a decrease in old animals. The expression of CKMT B chain (CBCK) was found to reduce in AD brain (Aksenov et al. 2000).

Note that although partial or non-toxic inhibition of a protein can induce compensatory responses in young animals, it is possible high oxidative stress can lead to an overall decrease in the total abundance of the proteins through rapid degradation of the synthesized protein or damaged translation. Extensive studies have revealed that oxidized proteins are recognized by proteases and completely degraded, entirely new replacement protein molecules are then synthesized de novo. In a recent paper, significant activity increases of succinate dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase, significant decreases of isocitrate dehydrogenase, and α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase were reported from AD brains (Starkov et al. 2004). Previous studies show a loss of CKMT activity in AD brain and increased levels of oxidatively modified CKMT (Yoo et al. 2001). The activity of cytochrome oxidase (COX) was reported to decrease with aging and this effect was shown more marked in AD (Cardoso et al. 2004; Ojaimi et al. 1999).

Proteins Exhibiting Decreasing Expression at 12 Months

Five subunits of Na+/K+ transporting ATPase were observed in this study with three (two isozymes of the large catalytic subunit (α2, and α3) and one glycoprotein subunit (β1)) observed in all the three ages. All the three forms exhibited elevated expression in PS-1 KI mice at 3 and 6 months of age compared to WT mice with an increase of about 60–100% (Table 2).

Altered Ca2+ regulation has been found to impair the function of ion-motive ATPase (Na+/K+ ATPase) (Mattson 1998; Xie and Askari 2002). Furthermore, the partial and non-toxic inhibition of this protein by increased Ca2+ was discovered to induce increased abundance of functional Na+/K+ ATPase in cardiac myocytes (Xie and Askari 2002). Na+/K+ transporting ATPases are integral membrane proteins responsible for establishing and maintaining the electrochemical gradients of Na+ and K+ ions across the plasma membrane for the maintenance of the ion gradients required for cell homeostasis. Na+/K+ ATPase can also function as signal transducer (Xie and Askari 2002). It was recently reported that the regulation of individual Na+/K+ ATPase isoforms is an important adaptive response to anxiety or learning behavior (Ashe 2001). Its appropriate function is directly relevant with the memory and cognitive functions of the brain. From the current results, at young ages, in spite of the inhibition by the deranged calcium homeostasis, the function level of this protein may still be kept by the compensatory increased expression. However, we observed at 12 months expression of Na/K ATPase in PS-1 KI mice decreased to about half of age-matched WT mice. The decrease in protein abundance suggests that in addition to functional inhibition that occurs at young ages there is also a loss of ability to synthesize protein. The decreased abundance of Na+/K+ ATPase can be explained by an increase of oxidative stress with age (Rose and Valdes 1994; Moseley et al. 2007; Petrushanko et al. 2006; Hattori et al. 1998). In aging studies, it is a well-accepted observation that oxidative stress increases with age. Evidence based on basal metabolic rate measurements indicates that whole-body Na+/K+ ATPase activity decreases with age. Furthermore, it has been observed that PS-1 mutations enhance the aging effects and increase oxidative stress. Direct evidence was recently reported by measuring the ROS level and lipid peroxidation in PS-1 KI mice (Schuessel et al. 2006). Significant impairment of Na+/K+ transporting ATPase has been reported in pathologic conditions associated with the development of oxidative stress such as Parkinson’s and AD, ischemia-reperfusion injury, apoptosis, intoxication, and aging (Petrushanko et al. 2006; Boldyrev and Bulygina 1997). Application of antioxidants and measures that efficiently reduce free radical production have been shown to restore Na+/K+ ATPase activity and provide cell survival (Chen et al. 2008).

Similarly, two nucleotide-binding proteins, G(I)/G(S)/G(O) gamma-2 subunit precursor (G gamma-I) and G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta 1 (Transducin beta chain 1), were present in all the three ages and were significantly increased in PS-1 KI mice at early ages and decreased at 12 months of age. Recent studies suggest that PS-1 regulates G0 protein activities in living cells (Smine et al. 1998). G proteins function as modulators in various transmembrane signaling pathways and are required for GTPase activity, involved in second messenger cascades as a component of signal transduction in cell physiology (Suo et al. 2004). Studies of levels of G proteins in AD brain show the proteins tend to be preserved although function tends to be impaired with progression of the disease. Recent studies showed that Aβ25-35 and Aβ1-40 caused a concentration-dependent increase in GTP binding (Karelson et al. 2005).

Another protein relevant to signal transduction is CNP which also showed increased expression in PS-1 KI mice at young ages and decreased expression at 12 months of age. The CNPs function as key players in controlling the duration and magnitude of cellular responses by reducing the intracellular levels of cAMP and cGMP. Cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP regulate a vast array of cellular activity by modulating the function of molecular switches in the cell. Levels of CNP in Down syndrome and AD brain were found to decrease (Vlkolinsky et al. 2001).

The relative expression value of 14-3-3ζ protein was observed to be ~1.5 at in PS-1 KI mice at 3 and 6 months, but decreased significantly to 0.77 at 12 months. The 14-3-3 proteins are a family of conserved regulatory molecules expressed in all eukaryotic cells. A striking feature of the 14-3-3 proteins is their ability to bind a multitude of functionally diverse signaling proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, and transmembrane receptors allowing it to play important roles in a wide range of vital regulatory processes, such as mitogenic signal transduction, apoptotic cell death, and cell cycle control (Fu et al. 2000). It was reported that neurofibrillary tangles of AD brains contain 14-3-3 proteins (Layfield et al. 1996). Furthermore, 14-3-3ζ was found to be an effector of tau protein phosphorylation (Hashiguchi et al. 2000).

Another protein identified and quantified with high confidence is EAAT2 (sodium-dependent glutamate/aspartate transporter 2) (GLT-1) which increased in young PS-1 KI mice but then decreased in older animals. The glial glutamate transporter EAAT2 is the main mediator of glutamate clearance. Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Its activity is carefully modulated in the synaptic cleft by glutamate transporters. Reduced function of EAAT2 could lead to accumulation of extracellular glutamate, resulting in a form of cell death known as excitotoxicity (Tian et al. 2007, Rinholm et al. 2007). The isozyme EAAT1 was found to decrease in aging and AD platelets (Zoia et al. 2004).

Summary

In summary, PS-1 KI mice showed extensive mitochondrial proteomic change in comparison to that of WT mice of the same age groups. In the aging process, Na+/K+ transporting ATPase, cytosolic brain CBCK, G proteins, EAAT, 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase, 14-3-3 protein theta, first exhibited elevated expression in the young ages, but abruptly decreased in their relative expression in aged animals. It was also observed that the OXPHOS proteins, VDACs, uMtCK, TIMs, Hexo, 60 kDa heat shock protein, phosphate carrier protein, calcium-binding mitochondrial carrier protein Aralar1, mitochondrial glutamate carrier 1, mitochondrial carrier homolog 2, had no significant change at the young ages, but were elevated significantly in PS-1 KI mice at 12 months of age relative to that in age-matched mice.

We propose that these proteomic alterations reflect disrupted calcium homeostasis and oxidative stress changes enhanced by the PS-1 mutation. In young animals Ca2+ elevation caused by the PS-1 mutation could inhibit the activity of Na+/K+ ATPases, G Proteins, and the other signal transduction proteins. This inhibition could induce increased expression of the protein as a compensatory response. At the same time Ca2+ elevations could activate the NADH shuttle and increase the NADH/NAD ratio in mitochondria. This activation could increase the production of ATP but will also enhance ROS generation. Then the disrupted ion homeostasis and accumulated oxidative stress would cause damages on the function of OXPHOS complexes and ANT, and other energy metabolism relevant proteins and induce their elevated abundances, again as compensatory response, to keep the ATP production level. Meanwhile, the increased oxidative stress at this aged stage will induce the decrease in the abundances of Na+/K+ transporting ATPase and other signal transduction proteins causing impairment in brain function in cognition and memory prior to the formation of pathologic lesions as observed in the transgenic models and AD cases. With this scenario, at even older ages the mitochondrial proteins including those of OXPHOS, MPTP, and Krebs cycle will decrease in quantity causing mitochondrial dysfunction and major neuronal cell death in the late AD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by National Institute of Health grant (NIH/NIA Grant # 1R01 AG25403-04). Our bioinformaics resources were supported by NCRR(NIH) Grant P 20 RR16481. The authors thank the University of Kentucky Mass Spectrometry Facility (http://www.rgs.uky.edu/ukmsf) for laboratory resources.

References

- Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Butterfield DA et al (2000) Oxidative modification of creatine kinase BB in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurochem 74(6):2520–2527. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe KH (2001) Learning and memory in transgenic modeling Alzheimer’s disease. Learn Mem 8:301–308. doi:10.1101/lm.43701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SM, Landar A, Darley-Usmar V (2005) Mitochondrial proteomics in free radical research. Free Radic Biol Med 38:175–188. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley JG, Duan W, Chan S et al (1999) Altered calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cortical synaptic compartments of presenilin-1 mutant mice. J Neurochem 1030–1039. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721030.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beinert H, Kennedy MC, Stout CD (1996) Aconitase as iron-sulfur protein, enzyme, and iron-regulatory protein. Chem Rev 96(7):2335. doi:10.1021/cr950040z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinert H, Holm RH, Munck E (1997) Iron-sulfur clusters: nature’s modular, multipurpose structures. Science 277(5326):653–659. doi:10.1126/science.277.5326.653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkich DA, Ola MS, Cole J et al (2007) Mitochondrial transport proteins of the brain. J Neurosci Res 85:3367–3377. doi:10.1002/jnr.21500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojarski L, Herms J, Kuznicki J (2008) Calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 52(4–5):621–633. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev A, Bulygina E (1997) Na/K-ATPase and oxidative stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci 834:666–668. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers B, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C (2008) Molecular genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Ann Med 40(8):562–583. doi:10.1080/07853890802186905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G et al (2005) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann Neurol 57:695–703. doi:10.1002/ana.20474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas E, Davies KJA (2000) Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med 29(3–4):222–230. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00317-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso SM, Proença MT, Santos S et al (2004) Cytochrome c oxidase is decreased in AD platelets. Neurobiol Aging 25:105–110. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Lin JK, Liu SH, Lin-Shiau SY (2008) Novel Regimen through combination of memantine and tea polyphenol for neuroprotection against brain excitotoxicity. J Neurosci Res 86:2696–2704. doi:10.1002/jnr.21706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras L, Gomez-Puertas P, Lijima M et al (2007) Ca2+ activation kinetics of the two aspartate-glutamate mitochondrial carriers, aralar and citrin. J Biol Chem 282(10):7098–7106. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610491200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortassa S, Aon MA, Marban E, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B (2003) An integrated model of cardiac mitochondrial energy metabolism and calcium dynamics. Biophys J 84:2734–2755. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz S, Parone PA, Martinou J-C (2005) Building the mitochondrial proteome. Expert Rev Proteomics 2(4):541–551. doi:10.1586/14789450.2.4.541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dencher NA, Frenzel M, Reifscheider NH et al (2007) Proteome alterations in rat mitochondria caused by aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1100:291–298. doi:10.1196/annals.1395.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C et al (1996) Increased Amyloid-beta42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 383:710–713. doi:10.1038/383710a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Subramanian RR, Masters SC (2000) 14-3-3 proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40:617–647. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomello M, Drago I, Pizzo P, Pozzan T (2007) Mitochondrial Ca2+ as a key regulator of cell life and death. Cell Death Differ 14:1267–1274. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4402147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC (1998) Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281:1309. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Sopher BL, Furukawa K et al (1997) Alzheimer’s presenilin mutation sensitizes neral cells to apoptosis induced by trophic factor withdrawal and amyloid beta-peptide: involvement of calcium and oxyradicals. J Neurosci 17(11):4212–4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Fu W, Sopher BL, Miller MW, Ware CB, Martin GM, Mattson MP (1999) Increased vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to excitoxic necrosis in presenilin-1 mutant knock-in mice. Nat Med 5(1):101–106. doi:10.1038/4789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rist B, Griffin TJ, Eng J, Aebersold R (2002) Proteome analysis of low-abundance proteins using multidimensional chromatography and isotope-coded affinity targets. J Proteome Res 1:47–54. doi:10.1021/pr015509n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DK, Eng J, Zhou H et al (2001) Quantitative profiling of differentiation-induced microsomal proteins using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol 19:946–951. doi:10.1038/nbt1001-946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KC, Schmitt-Ulms G, Chalkley RJ et al (2003) Mass spectrometric analysis of protein mixtures at low levels using cleavable 13C-isotope-coded affinity tag and multidimensional chromatography. Mol Cell Proteomics 2:299–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi M, Sobue K, Paudel HK (2000) 14-3-3ζ is an effector of Tau protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 275(33):25247–25254. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003738200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori N, Kitagawa K, Higashida T et al (1998) Cl−-ATPase and Na+/K+-ATPase activities in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurosci Lett 254:141–144. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00654-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber LA, Pfaller K, Vietor I (2003) Organelle proteomics: implications for subcellular fractionation in proteomics. Circ Res 92:962–968. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000071748.48338.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karelson E, Fernaeus S, Reis K et al (2005) Stimulation of G-proteins in human control and Alzheimer’s disease brain by FAD mutants of APP714–723: implication of oxidative mechanisms. J Neurosci Res 79:368–374. doi:10.1002/jnr.20371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R (2002) Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74:5383–5392. doi:10.1021/ac025747h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnoshita Y, Uo T, Jayadev S et al (2006) Potential applications and limitations of Proteomics in the study of neurological disease. Arch Neurol 63:1692–1696. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.12.1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layfield R, Fergusson J, Aitken A et al (1996) Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease brains contain 14-3-3 proteins. Neurosci Lett 209(1):57–60. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(96)12598-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutner S, Czech C, Schindowski K et al (2000) Reduced antioxidant enzyme activity in brains of mice transgenic for human presenilin-1 with single or multiple mutations. Neurosci Lett 292:87–90. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01449-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Burklen T, Yuan X et al (2006) Stabilization of ubiquitous mitochondrial creatine kinase preprotein by APP family proteins. Mol Cell Neurosci 31:263–272. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2005.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell MA, Xiong S, Maresbery WR et al (2005) Quantitative proteomic analysis of mitochondria from primary neuron cultures treated with amyloid beta peptide. Neurochem Res 30(1):113–122. doi:10.1007/s11064-004-9692-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCoss MJ, Wu CC, Liu H et al (2003) A correlation algorithm for the automated analysis of quantitative proteomics data. Anal Chem 75:6912–6921. doi:10.1021/ac034790h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP (1998) Modification of ion homeostasis by lipid peroxidation: roles in neuronal degeneration and adaptive plasticity. Trends Neurosci 20:53–57. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP (2007) Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell 6:337–350. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack JG, Halestrap AP, Denton RM (1990) Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol Rev 70:391–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha VK, Bunkenborg J, Olsen JV et al (2003) Integrated analysis of protein composition, tissue diversity, and gene regulation in mouse mitochondria. Cell 115:629–640. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00926-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PI, Santos MS, Oliveira CR (2007) Alzheimer’s Disease: a lesson from mitochondrial dysfunction. Antioxid Redox Signal 9(10):1621–1630. doi:10.1089/ars.2007.1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley AE, Williams MT, Schaefer TL et al (2007) Deficiency in Na, K-ATPase isoform genes alters spatial learning, motor activity, and anxiety in mice. J Neurosci 27(3):616–626. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4464-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson O, Tu H, Lei T et al (2007) Familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked mutations specifically disrupt Ca2+ leak function of presenilin 1. J Clin Invest 117(5):1230–1239. doi:10.1172/JCI30447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E et al (2003) A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 75:4646–4658. doi:10.1021/ac0341261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman FI (1772) Musgrave, M. Lardelli (2007) Alzheimer’s disease: amyloidogenesis, the presenilins and animal models. Biochim Biophys Acta :285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Budd SL (2000) Mitochondria and neuronal survival. Physiol Rev 80(1):315–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojaimi J, Masters CL, McLean C et al (1999) Irregular distribution of cytochrome c oxidase protein subunits in aging and AD. Ann Neurol 46:656–660. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199910)46:4%3c656::AID-ANA16%3e3.0.CO;2-Q [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri L, Pardo B, Lasorsa FM et al (2001) Citrin and aralar1 are Ca2+-stimulated aspartate/glutamate transporters in Mitochondria. EMBO J 20(18):5060–5069. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.18.5060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papassotiropoulos A, Fountoulakis M, Dunckley T et al (2006) Genetics, transcriptomics, and proteomics of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychol 67:652–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Contreras L, Serrano A et al (2006) Essential role of aralar in the transduction of small signals to neuronal mitochondria. J Biol Chem 281(2):1039–1047. doi:10.1074/jbc.M507270200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parihar MS, Brewer GJ (2007) Mitoenergetic failure in Alzheimer disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C8–C23. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00232.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrushanko N, Bogdanov E, Bulygina B et al (2006) Na-K-ATPase in rat cerebellar granule cells is redox sensitive. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290:R916–R925. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raha S, Robinson BH (2000) Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends Biochem Sci 25:502–508. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PH, McWeeney S, Park BS et al (2004) Gene expression profiles of transcripts in APP transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 13:1225. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders J, Zahedi RP, Pfanner N et al (2006) Toward the complete yeast mitochondrial proteome: multidimensional separation techniques for mitochondrial proteomics. J Proteome Res 5:1543–1554. doi:10.1021/pr050477f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinholm JE, Slettalokken G, Marcaggi P et al (2007) Subcellular localization of the glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT at the neuromuscular junction in rodents. Neuroscience 145:579–591. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AM, Valdes R Jr (1994) Understanding the sodium pump and Its relevance to disease. Clin Chem 40(9):1674–1685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten BP, Van der Kolk NM, Schafer S et al (2005) Age-related loss of synaptophysin immunoreactive presynaptic boutons within the hippocampus of APP751SL, PS-1M146L, and APP751SL/PS-1M146L transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 167:161–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlattner U, Dolder M, Wallimann T et al (2001) Mitochondrial Creatine Kinase and Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Porin Show a Direct Interaction That Is Modulated by Calcium. J Biol Chem 276(51):48027–48030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider I, Reverse D, Dewachter I, et al (2001) J Biol Chem 276(15):11539–11544. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010977200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger SJ, Edgar PF, Kydd R et al (2001) Proteomic analysis of the brain in the Alzheimer’s disease: molecular phenotype of a complex disease process. Proteomics 1:1519–1528. doi:10.1002/1615-9861(200111)1:12%3c1519::AID-PROT1519%3e3.0.CO;2-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuessel K, Frey C, Jourdan C et al (2006) Aging sensitizes toward ROS formation and lipid peroxidation in PS-1M146L transgenic mice. Free Radic Biol Med 20:850–862. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ (2002) Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298:789–791. doi:10.1126/science.1074069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS (2007) Presenilin: running with scissors in the membrane. Cell 131:215–221. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smine A, Xu X, Nishiyama K et al (1998) Regulation of brain G-protein Go by Alzheimer’s disease gene presenilin-1. J Biol Chem 273(26):16281–16288. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.26.16281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasic D, Tolia A, Dillen K et al (2006) Presenilin-1 maintains a nine-transmembrane topology throughout the secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 281(36):26569–26577. doi:10.1074/jbc.M600592200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkov AA, Fiskum G, Chinopoulos C et al (2004) Mitochondrial α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci 24(36):7779–7788. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Beglopoulos V, Mattson MP, Shen J (2005) Hippocampal spatial memory impairments caused by the familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1M146V mutation. Neurodegener Dis 2:6–15. doi:10.1159/000086426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo Z, Wu M, Citron BA et al (2004) Abnormality of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases at prodromal and early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: an association with early β-amyloid accumulation. J Neurosci 24(13):3444–3452. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4856-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow RH, Khan SM (2004) A “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses 63:8–20M. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Lai L, Guo H et al (2007) Translational control of glial glutamate transporter EAAT2 expression. J Biol Chem 282(3):1727–1737. doi:10.1074/jbc.M609822200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H, Nelson O, Bezprozvanny A et al (2006) Presenilins form ER Ca2+ leak channels, a function disrupted by familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked mutations. Cell 126:981–993. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlkolinsky R, Nigel Cairns N, Michael Fountoulakis M et al (2001) Decreased brain levels of 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide-3’-phosphodiesterase in Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 22:547–553. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00218-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo TD, Palsson BO (2007) Building the power house: recent advances in mitochondrial studies through proteomics and systems biology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C164–C177. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00193.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xiong S, Xie C, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA (2005) Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 93:953–962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M (2007) Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 7(5):635–646. doi:10.1586/14737159.7.5.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Askari A (2002) Na/K-ATPase as a signal transducer. Eur J Biochem 269:2434–2439. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L-R, Conrads TP, Uo T et al (2004) Global analysis of cortical neuron proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 3:396–907. doi:10.1074/mcp.M400034-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoia C, Cogliati T, Tagliabue E et al (2004) Glutamate transporters in platelets: EAAT1 decrease in aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 25(2):149–157. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00085-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.